developmental 16

1/29

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

30 Terms

exposure to language

infants exposed to language even birth and are interested in what they hear

DeCaspar and Spence (1986) exposure to language

• Mothers’ read 3 stories to their babies in womb twice daily for 6 weeks

• Two days after birth, showed preference for previously exposed stories (increased sucking frequency)

Speech sounds:

Infants prefer vocalisations to artificial sounds (Vouloumanos & Werker, 2007)

• Newborn infants (about 2 days old)

• Played synthetic voice sounds, human nonsense speech sounds

• Pacifier sucking study – more sucks to preferred sounds

• Preferred speech sounds

Vouloumanos et al. (2010):

• Played human nonsense speech sounds and Rhesus monkey vocalisations

• Newborns, no preference between human and Rhesus monkey vocalisations

• Also looked at three-month old infants (preferential looking). Preferred human vocalisations

Infants are primed to communicate

Discrimination of Speech Sounds (Eimas et al., 1971):

• Investigated infant phoneme recognition using /pa/ and /ba/ sounds

• Measured sucking frequency. Habituated to one sound (/pa/) then changed to another (/ba/).

• Infants (1 and 4 months old) discriminated in the same way as adults

-> children in an English speaking household

Specialisation with age

Differentiating phonemes from different languages

1–2-month-old infants can respond to phonemes from all languages (Kuhl et al., 1992)

As they get older, they start to specialise to their native language.

Werker & Tees (1984)

• Phoneme distinction for English native speaking infants, for different Hindi (blue) and Nthlakapmx (Canadian first nation language) (green) phonemes

• At 6-8 months, still good discrimination

• By 12-months, significantly less able to discriminate

• Ability to specialise is related to later language development:

• Kuhl et al. (2005) found a negative correlation between early specialisation and larger vocabularies

Word segmentation

Identifying words in a pattern of speech is also difficult

By 7-months olds, infants show a preference for words previously heard in a sentence string, to a novel word (Jusczyck & Aslin, 1995)

Discrimination between previously heard syllable sequences and novel sequences @ 8 months also suggests a recognition of the types of syllables used in a specific language (e.g. Aslin et al., 1998)

Discrimination of frequently used words – babies can recognise their own name by 4½ months

stages of early vocalisations

universality of babbling

Infants from different cultures babble some of the same consonant- vowel combinations (Thevenin et al., 1985)

However, can be identified as from a specific language by 8-10 months of age (de Boysson-Bardies et al., 1984)

Some evidence that deaf infants can babble verbally (Lenneberg et al., 1965) although later and less complex than hearing infants

Evidence that babies from deaf families “babble” with nonsense sign language (Pettito & Marentette, 1991)

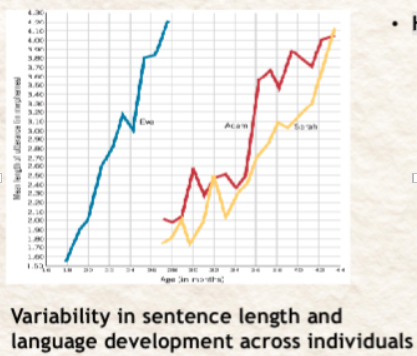

babbling and later language development

Roe (1975) – timing of peak of neutral vocalisations (cooing) was correlated with cognitive development Oller et al. (1998) -> the earlier babbling occurred, the greater the cognitive development that occurred

• Followed 1536 infants at high risk for language delay (being assessed because of risk of deafness, premature)

• Late canonical babbling (not present by 10 months) significantly predicted later developmental delay Walker & Bass-Ringdahl (2007)

• 19 infants with cochlear implants

• Complexity of babbling (following implants) predicted language skills (including vocabulary) @ 4 years of age

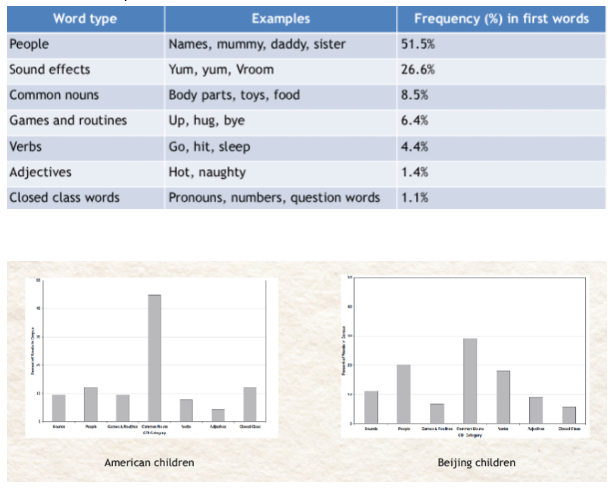

first words Tardif et al (2008)

Children aged 8-16mths speaking 1-10 words from

• USA – English (n=264)

• Hong Kong – Cantonese (n=367)

• Beijing – Putonghua (n=336)

Parents completed questionnaires listing common words and asked to identify which their child used.

Some similarities

Not universal – suggests importance of language exposure

Value of different elements of language – emphasis on correct address in Cantonese (paternal grandma, maternal grandma)

understanding and interpreting first word

• Adults’ interpretation of words used -> might not actually be first word

• Babbling identified as words

• Recognition of what’s spoken about – social referencing e.g. toy not known to observer

• Simplification of word, pronunciation (“nana”)

• Caregivers vs. other adults (“oooh” as shoe)

timing of speech development

the gavagai problem

a child acquiring language is facing the problem of the indeterminacy of translation when trying to understand the meaning of a novel word

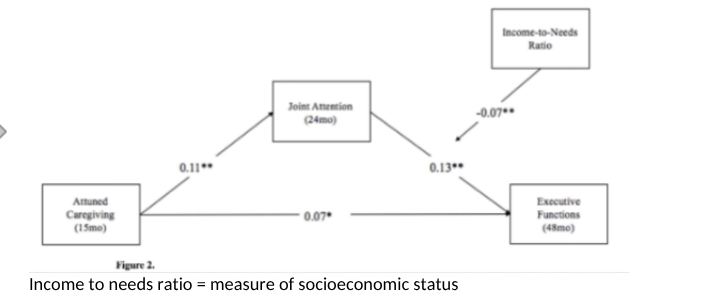

joint attention

• important to help understand the world

Relevant to language development and making sense of what is being communicated

– Intersubjectivity

– Social referencing

– Following attention

– Directing attention

• Aids label identification and words learning

intersubjectivity

– shared understanding of knowing that both looking at same thing

social referencing

baby looking at caregiver for a cue

following attention

baby is following where adult is looking

directing attention

child brings adult’s attention to what they’re referring to or vice versa

Fast mapping/word exclusivity

Children assume each object only has one label

If there is a known and new object, new object must relate to new word

Show me the “blicket”

(Markman & Wachtel, 1988)

-> knows what a dog is so uses process of elimination

pragmatic cues

• Social contexts to identify word use: adult attention or emotional response

Where’s the “gazzer” -> looks sad looking for the object, look in last bucket and look happy and relieved, children understand that the object is in the last bucket, even though they have never seen it before or know what it is

Akhtar et al. (1996)

linguistic context

• By using known grammatical cues, influences what a child understands by a certain word

“sibbing”, “a sibber”

Brown (1957)

common early errors

Overextension – using same word for many things

• Under extension – using a word in a restricted and individualistic way e.g. car for only the family’s car; dog for only their dog.

• Comprehension outstrips production – children understand more words than they can say

learning grammatical rules

• Plural: -s; Past tense: -ed

• Children learn these rules (Wug test)

• Irregular plurals (men, went)

– Initially the correct form is used (exemplar learning)

– Then the rule is acquired and overregularization occurs: e.g. mans, goed, foots, feets, breaked, broked

– Exceptions to the general rule are ‘re-learned’

exposure to speech to help make sense of the world

• We speak to infants from their first day of life

• Comments on infant behaviour

• Verbalisations of caregiving activities

• Grammatically well-formed

• Instructions on how to behave! (Reingold & Adams, 1980)

However, not all cultures speak directly to infants.

• Mayans in Mexico (Brown et al., 2002)

Parental/Adult Influences

• Intersubjectivity and learning turn-taking

• Labelling objects that have the child’s attention

• Use of infant directed speech to emphasise support word learning

• Parental scaffolding: repeating and building on child’s words. E.g. “dog” “yes, there is a spotty dog”

• Evidence that such scaffolding aids language development (Hoff, 2005)

• Playing word games (“where’s your nose? yes your nose is on your face”)

Adult responsibility

• Indication that there are individual differences in adults’ responsiveness to infant language

• Bornstein et al. (1991)

• Observed 30 children and their mothers @ 13 months & again at 20 months

• Looked at child and mother vocabulary and maternal responsiveness (timely and appropriate responses to child speech)

• Maternal responsiveness at 13 months, predicted child vocabulary @ 20 months

• Child vocabulary increases also predicted maternal responsiveness @ 20 months

Individual differences

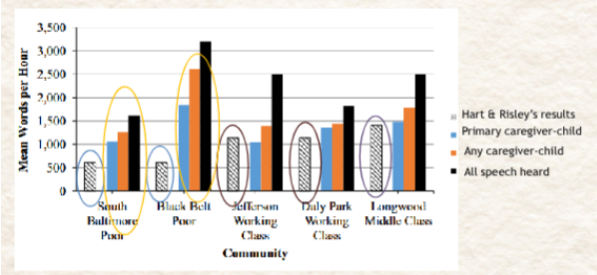

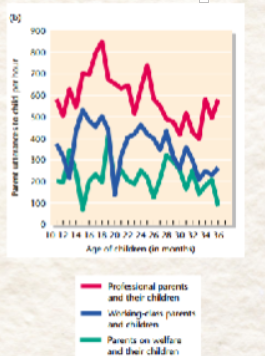

Hart & Risley (1995)

– Recorded the speech of 42 parents with their children from infancy to age 3 years

– Children of parents on welfare heard 616 words per hour

– Children of parents with low Social class 1251 words per hour

– Children of middle-class parents 2153 words per hour

– Evidence to link social class and word hearing to child vocabulary

Lower socioeconmic class = hear 30 million words less at home than those from higher socioeconoic class

-> only looked at caregivers

What type of speech are relevant? PS2011

• Sperry, Sperry and Miller (2019)

– Critique of Hart & Risley – looking just at direct mother-child speech

– Exposure to different types of language/speech e.g. other adults and overheard speech

– Considering other cultures where direct speech is less common/valued

– Replicated Hart & Risley’s study (n=42), also included other definitions of speech

• Direct caregiver-child speech

• All caregivers to child

• All speech in child’s hearing

Variability within and across groups is important

Different types of language exposure can be beneficial – especially if that’s what you’re used to

Every type of speech is relevant, not just caregivers

over 3,000 words an hour are heard from all speech