7010 Organization of Information Final Exam

1/112

Earn XP

Description and Tags

LSU Master's of Information Science; 7010 Organization of Information; Final Exam Study Set; Library and Information Science

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

113 Terms

subject analysis

identifying and describing what a resource is and what it is about

the part of the metadata creation process that identifies and articulates the subject matter and genre/form properties of the info resource being described

Why has the necessity for subject analysis been questioned?

advances in search engine technology and high costs of original cataloging

others have said that info resources don’e need to be analyzed because computers can identify some documents relevant to user’s needs when users are searching (though not all); the idea is that time and money spent on people doing subject analysis could be redirected to work on other projects.

even others have suggested computers can analyze documents and assign classification numbers and or descriptors from controlled vocabulary terms

Why are LIS professional reluctant to turn subject analysis over to computers?

despite advances, tech has not proven itself up to subject analysis

machines cannot assign concepts from subject languages with a degree of accuracy nor are they adept identifying the aboutness of info resources

computers can determine the words used in a doc or the frequency of their appearance, but they cannot understand the nuanced concepts represented by the words

they do not provide thoughtful analysis or insights into what content is most meaningful and cannot prioritize subject concepts

list the three important steps of subject analysis

examining a resource to determine what it is about (i.e. conceptual analysis)

describing the “aboutness” in a written statement

using that statement to assign controlled vocab terms and/or classification notations

Goals: to identify the intellectual and creative contents of info resources but also to ensure that individual resources are carefully and purposefully positioned within a collection

to provide users with subject access to info, to collocate resources of a like nature, and provide a logical location for similar tangible resources on the shelves

helps to alleviate retrieval problems associate with keywords and natural language through predictable use of controlled terminology and symbols

conceptual analysis

a comprehensive examination of physical properties and the intellectual or creative contents of an info resource

done to understand what the resource is (genre/form) AND what it is about (subject matter)

what are some challenges in subject analysis

subject analysis is not always clear and easy

cultural differences: concepts can be interpreted differently based on cultural backgrounds; people comprehend the world in different ways; we may see things differently based on things like education, language, cultural background; biases are also a part of this

consistency: individuals are not able to come up with the same natural language terms to describe a resource or to determine the same aboutness from a document

exhaustivity: the number of concepts that will be considered in the analysis; concepts included in the analysis and subject description can be guided by local policy, type of materials, and published guidelines for the translation

nontextual information: determining topics of contextual info resources is not as clear-cut than the process for the textual ones

objectivity: whether subject analysis can be an objective or impartial one; different ideas of whether we can be neutral or not (positivist vs constructivists)

What are the three levels of conceptual analysis for nontextual information?

The primary or natural subject matter: the factual level in which objects and events are identified (e.g. this is a painting of 13 long haired mean in robes gathered around a table); the of-ness of the resource (what it is an image of)

secondary or conventional subject matter: the iconographic level, in which some cultural knowledge of themes and concepts manifested in stories, images, and allegory needed (aboutness)

intrinsic meaning or content: iconological level, where the work is interpreted based on an understanding of the basic attitudes of a nation, a period, a class, a religious or philosophical viewpoint that is usually unconsciously condensed into a work (one that cannot be used to analyze visual images with any degree of consistency)

These are Panofsky’s three categories to understand how visual images can be analyzed.

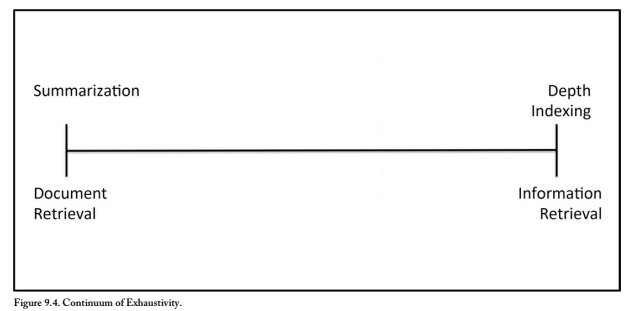

2 basic degrees of exhaustivity

summarization: identifies only a dominant overall subject of the resource, recognizing only concepts embodied in the main theme (in lib cataloging, subject analysis typically carried out at this level); allows for document retrieval (more likely to increase recall)

depth indexing: aims to extract all the main concepts addressed in a resource, recognizing subtopics and lesser themes (typically reserved for parts of resource like articles in journals, chapters in books); allows for retrieval at more specific level (more likely to increase precision)

precision vs recall

precision: measurement of how many documents retrieved are relevant

recall: measurement of how many of the relevant docs in a system are actually retrieved

exhaustivity affects both precision and recall

depth indexing more likely to increase precision because more specific terminology is used

summarization is likely to increase recall because the search terms are broader and more sweeping in their application in terminology

langridge’s approach for aboutness

views subject analysis as series of discrete activities

stresses conceptual analysis be performed independently from any particular classification scheme or controlled vocab

info prof must keep 3 basic questions in mind to determine aboutness

what is it? (answered by one of the fundamental forms of knowledge; is it resource for science? identifies 12 distinct forms of knowledge)

what is it for? (purpose of the document; why was it created? How might it be used?)

what is it about? (one or more topics everyday phenomena that we perceive)

wilson’s approach for aboutness

described 4 possible methods that one may use to come to an understanding of what a resource is about

purposive: one tries to determine

the creator’s aim or purpose in creating the information resource. If the creator gives a statement of purpose, then we may presume to know what the work is about.

figure-ground method: method, one tries to determine a central figure that stands out from the background of the rest of

the information resource. This might be an idea, a person, an object, a place—whatever is the central aspect of

the subject.

objective method: One tries to be objective by “counting” references to various concepts to determine which ones vastly outnumber the others. Unfortunately, something constantly referred to in the resource might be a background idea (e.g., Germany in a work about World War II). This method is also

difficult because a primary concept might be signified by different words throughout the resource.

cohesion method: looks at the unity of the content; one tries to determine what holds the work together, what content has been included, and what has been left out of the treatment of the topic.

use-based approach for aboutness

The main idea is that aboutness can be determined by looking at how a resource could be used or what questions a resource could answer.

what is it about?

why has it been added to our collection?

what aspects will our users be interested in?

three interconnected components of conceptual analysis

an examination of the physical resource (of display of digital resource)

examination of the intellectual or creative content

numerous simultaneously performed stages of aboutness determination

resource examination

a part of the conceptual analysis process

for textual resources, consider the following parts

cover, jacket, container

title, subtitle

table of contents

intro or preface

illustrations, diagrams, tables, and their captions

other bibliographic features such as dedications, hyperlinks, abstracts, indexes

the text

nontextual information

examine the object picture or other representation itself and translate ideas into words

content examination

part of conceptual analysis process

the various aspects of the intellectual and creative contents of the resource

identification of concepts

topics used as subject concepts: thinking in topical terms to identify subject of info resource

names used as subject concepts:

persons

corporate bodies

geographic names

titles

other named entities

chronological elements

Content characteristics:

research methods

POV

language, tone, audience, intellectual level

genre/form

stages of aboutness determination

input process: data is collected by encountering content in some form or manner (seeing, noticing, envisioning, etc.).

assumption making: assumptions about the resource’s aboutness are made. These assumptions may be about

macro-level, micro-level, or chapter-level aboutness, or they may be about other characteristics of the resource.

revision process: assumptions then undergo a revision process, in which assumptions are refined, reinforced, and/or

refuted.

sense making: Concurrently with the input, assumption making, and revision processes, the multifaceted process of

sense making begins.43 This entails a number of individual activities, including finding context, interpreting,

comparing, and reasoning.

stopping: final process centers on how and when one decides to stop the examination of the resource.

controlled vocabulary

a list of database of terms/phrases in which all terms representing a concept are brought together.

also known as a data value standard- a list of controlled values that can be used to populate a metadata element

similar to the idea of authority control, but it is usually for entities other than names and titles

3 major concerns in establishing a controlled vocabulary

consistency: In a controlled list, usually one of the terms representing the same concept is designated as the preferred or authorized term to be used in metadata descriptions. Choosing a term as the authorized one is an attempt to control synonyms and nearly synonymous terms. It ensures consistency, which allows for greater collocation of concepts in a retrieval tool.

relationships: The network of relationships is referred to as a vocabulary’s syndetic structure (i.e., its web of interconnections). Relationships among the authorized terms may be identified as references, broader terms, narrower terms, or related terms.

uniqueness: Each term in a controlled list should be unique and unambiguous. Definitions, scope notes, creation dates, identifier codes, associated classification numbers, categories, and other features can also assist with this

4 types of controlled vocabularies

simple term lists

synonym rings

taxonomies

thesauri (including subject heading lists)

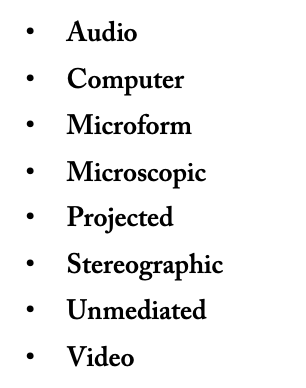

simple term list

aka pick list

not a sophisticated form of controlled vocab

It is a straightforward listing of limited values that may be used for a particular metadata element. There is no real concern about semantic relationships in a simple term list. These lists are usually presented in alphabetical or in some other logically evident order (e.g., geographic contiguity, chronological order).

E.g. RDA controlled vocab for media type element- consists of a straightforward alphabetical list of choices to describe the form of media a resource represents (audio, computer, microform, microscopic, projected, stereographic, etc.)

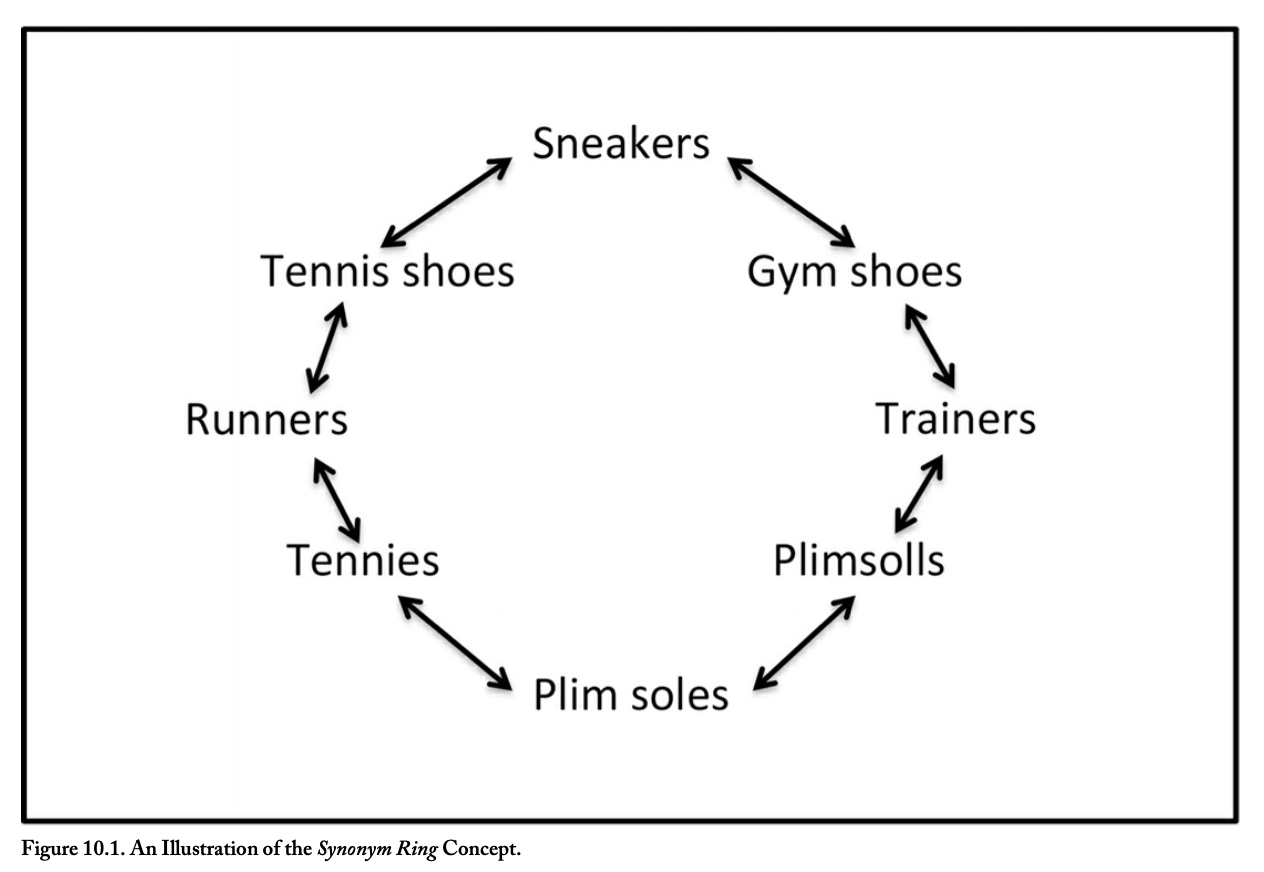

synonym ring

not meant to provide a list of terms to assign to documents, but instead used during retrieval activities

behind the scenes instrument in retrieval tools to connect equivalent terms/synonyms

made up of a number of equivalence tables or lists

used to broaden a search to enhance information retrieval so when a user searches on term in the clusters, all terms can be searched

a term can be authorized, but it’s not the focus of this controlled vocab

about improving retrieval among natural language variants

taxonomies

hierarchically ordered list of terms

an orderly classification illustrating a defined knowledge domain

often contains only preferred terms, not synonymous terms

can differ from thesaurus in that it has shallower hierarchies and less complicated structure

thesauri

most complex type of controlled vocab

an authority-controlled list of terms in which semantic relationships are identified

focus is on hierarchical structures, but also include reciprocal equivalence and associative relationships

usually made up of single terms and bound terms representing single concepts (type a personality)

subject heading list

a specialized types of thesaurus

created primarily in libraries

allows more complexity in structure of its authorized terms

includes single terms, bound concepts, compound phrases, and intricately constructed strings of terms

Think LCSH

thesauri v. subject heading lists

subject heading lists

created largely in libraries

tend to be more general in scope, covering broad subject area or entire reach of knowledge

thesauri

largely created in indexing communities

more strictly hierarchical

typically narrower in scope, comprising terms from one specific subject area

more liklely to be multilingual

usually made up of single terms so equivalent terms in other languages are easier to find and maintain

Both attempt to provide subject access, both choose preferred terms, and make references to non-used terms; both provide structural hierarchies

(p. 328)

controlled vocabulary challenges

specific vs general terms: level of specificity must be decided at outset of establishing controlled vocab; To some extent the decision on this matter is based on the types of users who are expected to search for headings from the list and upon the nature of the information resources that are to be assigned terms from the list. (329)

cats vs longhair cats vs Persian cat vs silver Persian cat

synonymous concepts: In the creation of a controlled vocabulary it is necessary to identify all the synonymous and nearly synonymous terms that should be brought together under a single authorized term.

For example, do the terms apparel, clothes, clothing, costume, dress, and garments all mean the same thing? If not exactly the same, or if they have different nuances, are the differences important enough to warrant separate vocabulary terms for them?

word form for one-word terms: Words in English often have more than one form that can mean the same thing (e.g., clothing and clothes). Also, language evolves, and as it does, a concept has a tendency to be expressed first as two words, then as a hyphenated word, then as one word

(e.g., meta data, meta-data, metadata)

sequence and form for multi-word terms and phrases: In some controlled vocabularies there are terms and phrases made up of two or more words. Some of these headings are modified nouns (e.g., Environmental education); others are phrases with conjunctions or prepositions (e.g., Information theory in biology); and a third group has qualifiers added in parentheses; A problem in constructing such terminology in a controlled way is being consistent in the order and form of the individual words used.

For example, the phrases energy conservation and conservation of energy resources mean the same thing.

Homographs and Homophones:

homographs are words that look the same but have different meanings; in a controlled vocabulary there must be some way to differentiate among the various meanings. Two common ways are either to use qualifiers to distinguish between the terms or to choose synonyms as the preferred terms.

note they may not be pronounced the same

homophones: words that are spelled differently but pronounced the same

moat and mote

foul and fowl

have also been ignored in controlled vocabularies in a visual world (e.g., moat and mote; fowl and foul). However, because what appears on computer screens is now quite regularly read aloud electronically to people with visual impairments, we need to give attention to pronunciations of homographs and to distinguishing among homophones.

Qualification of terms: when qualifiers are added to terms to clarify its meaning

abbreviations, acronyms, initialisms:

abbreviations: shortened forms of words

acronyms: abbreviations made up of initial letters of words from a phrase and resulting group of letters is pronounced as a word (radar)

initialisms: abbreviations made up of initial letters of a phrase, but each letter is pronounced separately (ABC for American Broadcasting Company

Without the ability to assume a certain population, it is best to assume that they should be spelled out. A few, however, have global recognition.

Popular vs technical terms: When a concept can be represented by both technical and popular terminology, the creators of a controlled vocabulary, sometimes called taxonomists in specialized subject communities, must decide which will be used.

subdivision of terms: A subdivision is a term or phrase appended onto a subject heading to provide additional specificity. (Chemistry - Dictionaries)

Compound Concepts: most thesauri primarily comprise single words and bound terms representing single distinct concepts. Other controlled vocabularies, however, include multitopic concepts in the form of phrases. When creating a controlled vocabulary, the taxonomist must determine how much compounding is desirable or acceptable, when to employ compounding (rather than employing single concepts), and what forms these phrases should take (332)

homographs

words that look the same but have different meanings

Mercury can be a liquid metal, a planet, a car, a Roman god

bridge can be a game, a structure spanning a chasm, a device connecting computer networks, a location on a ship, a dental device, etc.

pre-coordination vs. post-coordination

how controlled vocab terms are assigned

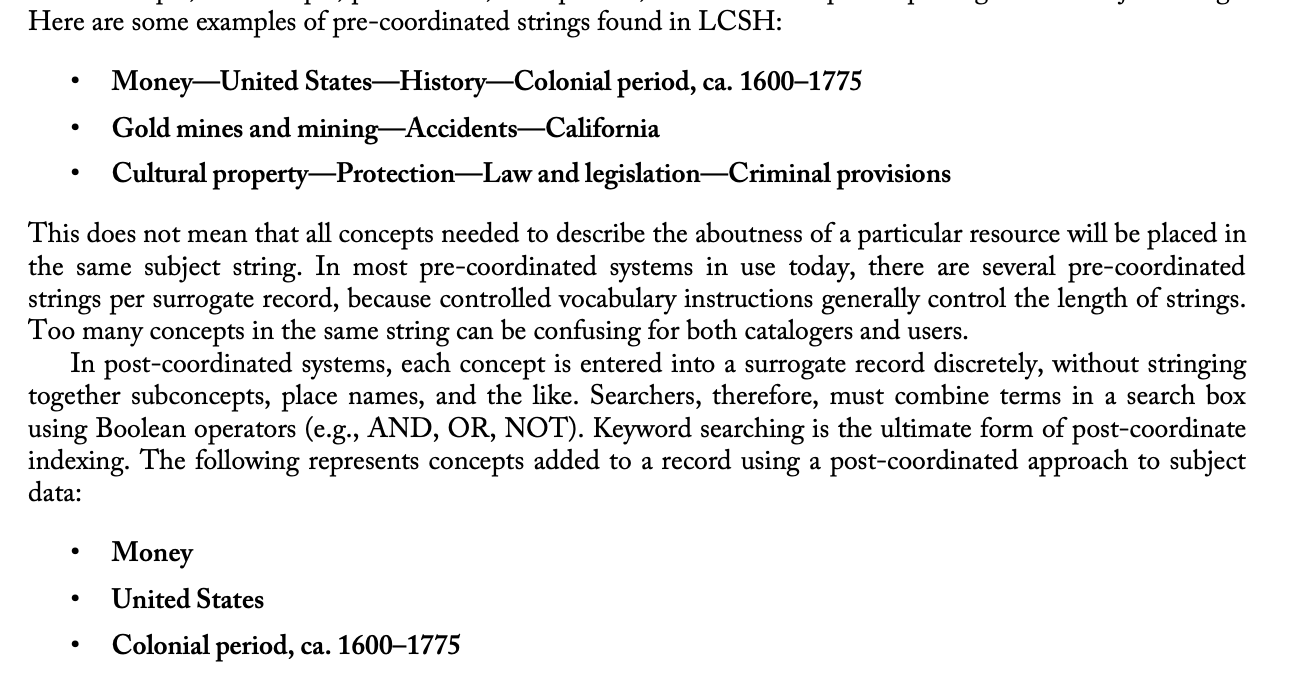

pre-coordinated fashion: the indexer constructs subject strings with main terms followed by subdivisions; When terms are pre-coordinated in the controlled vocabulary or are pre-coordinated by the cataloger or indexer, some concepts, subconcepts, place names, time periods, and form concepts are put together in subject strings.

This does not mean that all concepts needed to describe the aboutness of a particular resource will be placed in the same subject string. In most pre-coordinated systems in use today, there are several pre-coordinated strings per surrogate record, because controlled vocabulary instructions generally control the length of strings. Too many concepts in the same string can be confusing for both catalogers and users.

The pre-coordinated strings make clear the places and times in which the major topics are addressed.- they provide context

Money-United States-History-Colonial period, ca. 1600-1775

Gold mines and mining-Accidents-California

post-coordinated fashion: requires the searcher of the system to combine the terms (i.e., search the two or more terms together).

In post-coordinated systems, each concept is entered into a surrogate record discretely, without stringing together subconcepts, place names, and the like. Searchers, therefore, must combine terms in a search box using Boolean operators (e.g., AND, OR, NOT). Keyword searching is the ultimate form of post-coordinate indexing.

do not make it clear the places and times in which major topics are discussed

Money

United States

Colonial period, ca. 1600-1775

general principles for creating controlled vocabularies

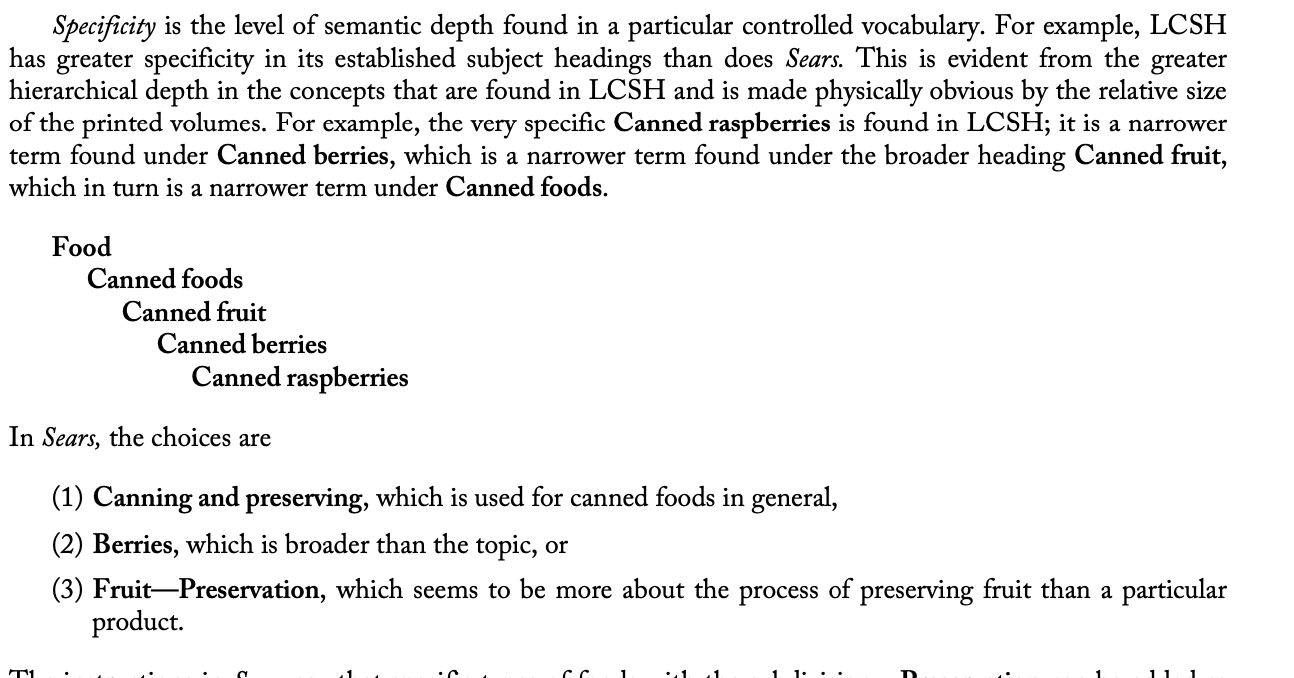

specificity: the level of semantic depth found in a particular controlled vocabulary.

E.g. the use of canned berries or canned raspberries in LCSH vs the choices in Sears of canning and preservation, or berries, or fruit-preservation

literary warrant: This means that terminology is added to a subject heading list or thesaurus only when a new concept shows up in the literature and therefore needs to have specific terminology established. (bottom-up approach); p. 334

direct entry: states that a concept should be entered into the vocabulary using the term that names it rather than treating that concept as a subdivision of a broader concept; p.335

in LCSH, preference for modified term to express a concept (Railroad stations) over the use of a broader term subdivided by a narrow term (e.g. Railroads- Stations)

general principles for applying controlled vocabulary terms

specific entry: a principle wherein the aboutness concept should be assigned the most specific term that is available in the controlled vocabulary ; allows an experienced user to know when to stop searching for an appropriate controlled vocab term

coextensive entry: the idea that the subject headings applied to an information resource will cover all, but no more than, the concepts or topics covered in that resource; is about matching exactly the subject entries to the limits and scope of the aboutness of an info resource

number of terms assigned: there should be no arbitrary limit on the number of terms or descriptors assigned

concepts not in the controlled vocabulary: if a concept is not present in such vocabulary it should be represented by a more general concept rather than simply adding unauthorized terms to the record

index terms for names

a separate authority file that generally controls most proper names

mechanics of controlled vocabularies

equivalence relationships

hierarchical relationships

associative relationships

lexical relationships

equivalence relationships

the relationship between synonymous (clothes and clothing) and nearly synonymous terms (seawater and oceanwater)

when the preferred way of expressing a concept is connected to synonymous ways of expressing it

usually represented by thesaurus labels USE or UF (used for)

unauthorized terms may also appear as entry vocabulary to act as pointers to the chosen terms

hierarchical relationships

a relationship in which a term is designated as being subordinate (or narrower than) another term

identified by relationship designators BT and NT

different kinds of these relationships

genus-species: type of relationship that indicates the narrower terms are a type or kind of whatever the broader term represents (e.g. Building - narrower terms are auditoriums, church buildings, clubhouses, garages)

whole-part: when the broader term represents the whole and the narrower term represents the parts (e.g. Head - narrower terms are brain, ear, face, hair, mouth, nose)

instance: the BT is a particular category of thing and each NT is an example or instance of the thing (e.g. Seas- NT are Adriatic Sea, Aegean Sea, Caribbean Sea)

associative relationships

usually designated as related term; indicate a relationship that might be of interest but is not a hierarchical or equivalence based relationship

are reciprocal

kinds of related-term relationships

one term is needed in the definition of the other (stamps needed in definition philately)

meanings of two terms overlap or may be used interchangeably, but they are not synonyms (Carpets and rugs)

linking of persons and their fields of endeavor (attorneys and law)

lexical relationships

relationships generally shown in lexical database WordNet

synonyms: terms that have same or nearly same meaning

coordinate term: therms that might be called siblings (have a same parent term)

hypernyms: parent terms; category comprising all instances that are “kinds of” the hypernym (family is hypernym for nuclear family, foster home)

hyponymns: designate child terms (foster family in example above)

holonyms: the name of the whole of which the meronyms are the parts (a family has its members: children, parents, sister, siblings)

meronyms: terms designate constituent parts of members of the whole (sister in the example above)

antonyms: terms with opposite meanings)

examples of controlled vocabulary standards

Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH)

Sears List of Subject Headings (Sears)

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

Library of Congress Genre/Form terms for library and archival materials (LCGFT)

Library of Congress Demographic Group Terms (LCDGT)

Art and Architecture Thesaurus (AAT)

Thesaurus of ERIC Descriptors (ERIC)

Faceted Application of Subject Terminology (FAST)

Library of Congress Subject Headings

LCSH

list of terms to be used as controlled vocab for subject concepts by the Library of Congress and by any other agency that wishes to provide such controlled subject access to their metadata descriptions

an all-purpose, multidisciplinary vocabulary

contains references, scope notes, and subdivisions to make headings more specific

used in conjunction with the Subject Headings manual during subject cataloging process (502)

Sears List of Subject Headings

Sears

controlled vocab of terms and phrases used primarily in small libraries to provide subject access to resources available from those libraries

main users are school and small-medium public libraries

follows LCSH in format and terminology choices

uses more general terms and does not include more specific terms or ones geared toward research audiences

has less subdivisions

Medical Subject Headings

MeSH

controlled vocabulary created and maintained by the national library of medicine for subject concepts in the field of medicine

has strict hierarchical structure

does not identify specific BTs and NTs, but uses the hierarchy to show relationships

LCGFT

Library of Congress Genre/Form Terms for Library and Archival Materials

used by libraries and archives to describe what a resource is, rather than what it is about.

contains genre/form headings to represent literary genre, artistic form, publication format of resources

does not include terms associated with ethnicity, nationality, audience, creation dates, geography, or popularity

does not allow for subdivision of terms

LCDGT

Library of Congress Demographic Group Terms

a thesaurus of demographic terms

demographic group is any subset of the general population centered on a particular defined characteristic

includes 11 categories of terms: age groups, education levels, ethnic/cultural group, gender groups, language groups; medical, psychological, and disability category; national/regional groups; occupations and fields of activity; religion groups; sexual orientation groups; social groups

Art and Architecture Thesaurus

AAT

intended to assist verbal access to all kinds of cultural heritage information

terms for describing objects, textual materials, images, architecture, and material culture

used in archives, libraries, museums, visual resource collections, and conservation agencies

arranged in 8 facets that progress from abstract to concrete

associated concepts: abstract concepts and phenomena; ideologies; attitudes; social or cultural movements

physical attributes: observable/measurable characteristics of artifacts and materials

styles and periods: terms for styles, periods, cultures, nationalities

agents: designations of people, animals, and plants

activities: actions, endeavors, occurrences

materials: substances used to produce structures or artifacts

objects: things

brand names: objects, materials, and activities known by brand names

facets are divided into one or more hierarchies

Thesaurus of ERIC descriptors

ERIC= acronym for the educational resources information center, which is a national information system designed to provide access to a large body of education-related literature;- ERIC indexes journal articles, descriptions and evaluations of programs, book reviews, research reports, curriculum and teaching guides, instructional materials, position papers, computer files, and resource materials

all of these materials are indexed using Thesaurus of Eric Descriptors

Faceted Application of Subject Terminology

FAST

the result of cataloger dissatisfaction with LCSH and other more complicated vocabularies

FAST is a faceted vocabulary, so terms are divided into defined categories representing particular aspects or angles of the subject matter

topical- general subject matter

geographic- place names

chronological- time periods

events-occurrences or historical incidents

personal names- names of persons

corporate names- names of organizations or groups

titles-names associated with works

genre/form- types or kinds of bibliographic structures, literary or artistic forms or formats

FAST allows for some subdivisions, but each facet’s main headings can be subdivided by subdivisions from the same facet (topical headings with topical subheadings)

ontologies

not just another type of controlled vocabulary

similar to thesauri in that they address relationships among concepts but there are differences

purpose of ontology is more far-reaching than a controlled vocab

thesaurus is focused on addressing synonyms, homographs, hierarchy, etc.

ontology’s purpose is not just lexical but an attempt to represent the reality or essence of a situation, knowledge domain, or conceptual framework through formal definitions and specific relationships

like a cross between a controlled vocab and a conceptual model

ontology describes

the types of things that exist (classes)

the relationship between them (properties)

the logical ways those classes and properties can be used together (axioms)

a formal representation to machines of what, to a human, is common sense or reality; a formal naming of entities that exist for a particular domain, with an attempt to define the types, properties, and relationships among them, which then define the essence of a situation, domain, or conceptual framework

useful for enhancing interoperability among systems in different knowledge domains or creating intelligent agents that can perform certain tasks

a building block for the semantic web

natural language processing

NLP research aims to enable computers to interpret and react to human languages

goals of NLP: machine translation, question answering, creating conversational agents, and dialog systems; and connected to question answering is improved and enhanced information retrieval

IR process: 1. interpret user’s info needs as expressed in free text; 2. represent the complete range of meaning conveyed in documents; 3. “understand” when there is a match between the user’s info need and all the docs that meet

To accomplish NLP tasks, challenges need to be met (see pg 520 for list).

Successful NLP systems contain info about the different areas of linguistics

phonetics: the study of how individual sounds are created and perceived

phonology: the study of patterns of sounds in languages and how they combine to form syllables

morphology: the study of the unites of meaning in a language (prefixes, suffixes, modifying word meaning)

syntax: the study of how words combine to create phrases and sentences and what combinations are allowed in different languages

semantics": study of meaning in language and the relationship between words and what they represent

discourse analysis: study of how information is exchanged across sentences and how that context informs semantic interpretation

pragmatics: study of how context affects interpretation

keywords

one of the first approaches used by NLP researchers was manipulation of keywords

success of keyword searching depends on 2 assumptions

that authors writing about the same concepts will use the same words in their writings

searchers will be able to guess what words those authors used for the concept

problems with keyword searching

not all related information was retrieved

searches often led to the extraction of irrelevant materials

synonyms list was used, but failed because lists were not large or general enough; they were implemented in very small, specialized domains

the lists did not attempt any level of word role assignment (aircraft can substitutes for plans; big can substitute for large; but big aircraft cannot substitute for large plans b/c system had no knowledge of adjectives and nouns and which kinds of words could be used together to make a phrase

tagging

recent venture into NLP

a populist approach to description; a process by which a distributed mass of users applies keywords (tags or hashtags) to various types of resources for the purposes of collaborative information organization and retrieval

grew with advent of social media

not a common feature in LIS institutions

allows individual users to group similar resources together by using their own terms or labels with few or no restrictions

tags can be based on various facts: subject matter, form, purpose, time, location, tasks or status, affective or critical reactions, myriad other reasons (525)

tags then used for searching or are displayed in alphabetical format

value of external tagging is people using their own vocabulary and adding explicit meaning

aggregated set of tags = folksonomy

lacks all the benefits of controlled vocabularies

folksonomy

an aggregation of tags created by a large number of individual users

a user-generated classification, emerging through bottom-up consensus

weaknesses: lack precision in language, lack syndetic structures, don’t work well in retrieval, and do not scale well

strengths: do reflect general populace’s language and needs, inclusive of everyone’s input, helpful for understanding resources, low cost

idea is if enough users tag resources, sufficient data can be aggregated to achieve stability, reliability, and consensus

classification

the placing of subjects into categories; in organization of information, classification is the process of determining where an information resource fits into a given hierarchy and often then assigning the notation associated with the appropriate level of the hierarchy to the information resource and its metadata

has specific connotations in libraries

views as a comprehensive hierarchical structure for organizing information resources on linear shelves

in LIS, has 3 distinct but related concepts

a system of classes, ordered according to a predetermined set of principles and used to organize a set of entities

a group or class in a classification system

the process of assigning entities to classes in a classification system

an artificial process by which we organize things for presentation or later access

categorization

the cognitive function that involves grouping together like entities, concepts, objects, resources, and so on.

considered to be broader and more abstract than classification

not a structured process used to systematically arrange physical resources

an amorphous or less well defined grouping

a natural process that humans do as part of their cognitive fundament

taxonomy

a classification or controlled vocabulary, usually in a restricted subject field, that is arrange to show presumed natural relationships

famous example: Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae

a lot of confusion regarding this term, categorization, and classification

rise and fall of classical theory of categories

roots of contempt classification system can be traced back to Aristotle’s classical theory of categories; were 10 states of being or 10 states of things that can be expressed about an object or an idea

Aristotle’s categories: substance; quantity; quality; relation; place; time; position; state; action; affection

placed objects or ideas into same category based on what they have in common; was unchallenged until mid-20th century b/c people understand a category to be an abstract container where things fall inside or outside the container- this was challenged with objects that fell in between or in grey areas

cracks in classical theory of categories

Ludwig Wittgenstein showed that category like game does not fit in the classical mode b/s it has not single collection of common categories; a game may be for education, amusement, or competition; may involve luck or skill; has no fixed boundary because new games can be added to it; Wittgenstein proposed to unite games into what we call a category

Lotfi Zadeh introduces fuzzy set theory

Floyd Lounsbury studied Native American kinship systems and chipped away at classical theory

Brent Berlin and Paul Kay also looked at colors to crack this theory more

Prototype theory brings first major crack in classical theory of categories (pg. 543-546)

fuzzy set theory

Lotfi Zadeh

a theory that holds that some categories are not well defined and sometimes depend upon the observer, rather than upon a definition (e.g. people who are under 5 ft tall think the category tall people is larger than do people who are over 6 ft tall)

prototype theory

developed by Eleanor Rosch

the theory that categories have prototypes (i.e. best examples) e.g. most people think a robin is a better example of a bird than an ostrich

if classical theory were right, then no members of a category should better represent the category than others; but this isn’t the case

ad hoc categories matter too- those that are made up on the spur of a moment; people will put different things into a category such as camping gear depending upon their experience, where they are going, how they will camp, and so on.

hierarchical classification scheme

most schemes are hierarchical arrangements (Dewey Decimal Classification, Expansive Classification, Library of Congress Classification, Universal Decimal Classification, Colon Classification, Bibliographic Classification 2nd ed.

begin with broad, top-level categories, the branch into any number of subordinate levels (moving from general to specific) and creating a tree structure

enumerative classification scheme

schemes that attempt to assign a designation for every subject concept (both single and composite) needed in the system

all schemes have elements that are enumerative, but some have more than others

LCC is more enumerative than DDC because it attempts to list a notation for every possible topic with its 21 main classes

faceted classification

attempts to include all possible subjects, but it does not do this by creating a singular place in a hierarchy for each topic (with its own specified number)

made up of many discrete topics

an attempt to divide universe of knowledge into its component parts and then to gather those parts into individual categories or facets

within each facet, topics are assigned individual notation

This concept of faceted classification was named first by Ranganathan in his explanation of his Colon Classification. CC provides lists of symbols for single concepts, with rules for combining them into complex concepts. This approach is also referred to as analytico-synthetic classification, because the classification is established through an analysis of topics into component parts and then notation is synthesized from those parts.

he posited 5 fundamental categories that can be used to illustrate the facets of a subject

Personality (P): the focal or most specific aspect of the subject

Material or Matter (M): a component

Energy (E): an activity, operation, process

Space (S): a specific or generic place or location

Time (T): a chronological period, a year, a season

also known as PMEST

components that major bibliographic classification schemes have in common

A verbal description, topic by topic, of the things and concepts that can be represented in or by the scheme.

An arrangement of these verbal descriptions in classed or logical order that is intended to permit a meaningful arrangement of topics and that will be convenient to users.

A notation that appears alongside each verbal description, which is used to represent it and which shows the order. The entire group of verbal descriptions and notations form the schedules.

References within the schedules to guide the classifier and the searcher to different aspects of a desired topic or to other related topics (like the related term references in alphabetical lists).

An alphabetical index of terms used in the schedules, and of synonyms of those terms, that leads to the notations.

Instructions for use. General instructions (with examples) are usually to be found at the beginning of the scheme, and instructions relating to particular parts of the schedules are, or should be, given in the parts to which they relate.

An organization that will ensure that the classification scheme is maintained, that is, revised and republished. This is external to the scheme, but an important factor in evaluating its comparative usefulness

Koch’s four broad varieties of classification schemes

Universal schemes: schemes that cover the universe of knowledge.g., DDC, UDC, LCC, CC,BC2);

National general schemes: similar to universal schemes, but designed for use in a single country (e.g., Nederlandse Basisclassificatie in the Netherlands )

subject specific schemes: schemes that cover a particular subject area or knowledge domain (e.g., Iconclass for art resources; National Library of Medicine Classification, and the Mathematics Subject Classification for their obvious subject matter)

home-grown schemes: chemes created to address the needs of a particular service or institution (e.g., Metis: Library Classification for Children, a set of 26 broad categories labeled A to Z established by four librarians who worked at the Ethical Culture School in New York City

broad classification vs close classification

broad: classification that uses only the main classes and divisions of a scheme and perhaps only one or two levels of subdivisions.

close: classification that uses all the minute subdivisions that are available for very specific subjects.

here is that if the intent of using the scheme is to collocate topics, then broad versus close may depend upon the size of the collection that is being classified. If the collection is very large, then using only the top levels of the scheme means that very large numbers of resources, or the surrogate records for them, will be collocated at the same notation. On the other hand, if the collection is very small, then using close classification may mean that most notations are assigned to only one or two resources, with the result that collocation is minimal

classification of knowledge vs. classification of a particular collection

Classification of knowledge is the concept that a classification system can be created that will encompass all knowledge that exists. DDC began as a classification of knowledge—at least Western knowledge as understood by Melvil Dewey.

Classification of a particular collection is the concept that a classification system should only be devised for the information resources that are being added to collections, using the concept of literary warrant.

Even though DDC began as a classification of knowledge, it has been forced to use literary warrant for updates and revisions.

integrity of numbers vs keeping pace with knowledge

Integrity of numbers is the concept that in the creation and maintenance of a classification scheme, a notation, once assigned, should always retain the same meaning and should never be used with another meaning.

Keeping pace with knowledge is the concept that in the creation and maintenance of a classification scheme, it is recognized that knowledge changes, and therefore it is necessary to be able to move concepts, insert new concepts, and to change meanings of numbers.

closed vs open stacks

Closed stacks is the name given to the situation where information resource storage areas are accessible only to the staff of the library, archives, or other place that houses information resources.

Open stacks is the name given to the opposite situation, where patrons of the facility have the right to go into the storage areas themselves.

In closed stack situations users must call for resources at a desk and then wait for them to be retrieved and delivered. This eliminates any possibility of what is called browsing in the stacks. Browsing is a process of looking, usually based on subject, at all the resources in a particular area of the stacks, or in a listing in an online retrieval tool, in order to find, often by serendipity, the resources that best suit the needs of those browsing.

fixed vs relative location

fixed location signifies a set place where a physical information resource will always be found or to which it will be returned after having been removed for use. A fixed location identifier can be an accession number; or a designation made up of room number, stack number, shelf number, position on shelf; or other such designations.

relative location is used to mean that an information resource will be or might be in a different place each time it is reshelved; that is, it is reshelved relative to what else has been acquired, taken out, returned, and so forth, while it was out for use. The method for accomplishing this is usually a call number with the top line or two being a classification notation.

location device vs collocation device

location device is a number or other designation on a resource to tell where it is located physically. It can be, among other designators, an accession number, a physical location number, or a call number.

collocation device is a number or other designation on a resource used to place it next to (i.e., collocate with) other resources that are like it. It is usually a classification notation.

Another controversy surrounding classification is that of whether classification serves as a collocation device or whether it is simply a location device.

classification of serials vs alphabetical order of serials

Serials are sometimes called journals or magazines. A serial may be defined as a publication issued in successive parts (regularly or irregularly) that is intended to continue indefinitely.

Classification of serials means that a classification notation is assigned to a serial, and this classification notation is placed on each bound volume and/or each issue of that serial.

Alphabetical order of serials means that the serials are placed in order on shelves or in a listing according to the alphabetical order of the titles of the serials. The concerns involved in the classification versus alphabetical order dilemma apply to runs of printed serials.

classification of monographic series as separately vs as a set

A monographic series is a hybrid of monograph and serial. In a monographic series each work that is issued as a part of the series is a monograph but is identified as one work in the series. The series itself may or may not be intended to be continued indefinitely.

The difficulty with classification of monographic series is whether to classify each work in the series separately with a specific notation representing its particular subject matter, or to treat the series as if it were a multivolume monograph and give all parts of the series the same (usually broad) classification notation representing the subject matter of the entire series.

use of categories and taxonomies online

The use of categories or taxonomies (the terminology seems to depend upon the site) is readily apparent online. On a commercial shopping site like Amazon.com28 or a website for a large-scale retailer, such as the grocery store known as Wegmans,29 a taxonomy is often found directly on the homepage or in a pull-down menu (or both). An information architect created this taxonomy to provide shoppers with a quick, user- friendly set of links to the main divisions in order to improve navigation and the overall experience of the site, as well as the ability to find information and products quickly and efficiently

The difficulty with taxonomies at some commercial sites like Amazon.com is the overwhelming size of the overall inventory, and the unpredictability of the hierarchies employed. Even at the deepest, most specific levels of a taxonomy, there still may be too many resources to browse and the user still may need to conduct a keyword search.

Taxonomies also are used by noncommercial sites, such as the National Center for Biotechnology Information’s public databases.30 But, perhaps, the most well-known example of using categorization online was the Yahoo! Directory, where, before it closed in 2014, websites were placed into categories created by Yahoo! indexers, and the categories were browsed in hierarchical fashion.

categorizing search results

Some researchers believe that search satisfaction and effectiveness could be improved if classification techniques were applied to search engines.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the now defunct Northern Light, a free and publicly available search engine, used document-clustering techniques to divide search results into broad subject categories. While it did not work directly with a formal classification system, Northern Light used document clustering to improve the user’s ability to navigate through results sets. At the time, Northern Light was the only major search engine to use these techniques for displaying results.

What is document clustering? clustering is a computer science approach to classifying documents in a collection, based on the contents of the entire collection. They state, “It explores collection relationships by computing the similarity between every pair of documents in the collection. Using the similarity information, clustering attempts to divide a collection of documents into groups (clusters).”37 As a result, documents in the same clusters are more similar than documents in different clusters.

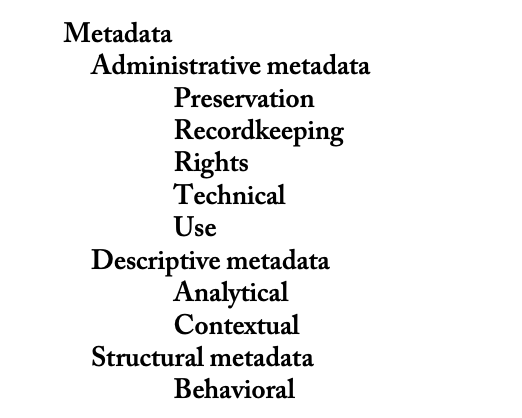

metadata

data about data.”

what varying definitions of metadata have in common is the notion that metadata is structured information that describes the important attributes of information resources for the purposes of identification, discovery, selection, use, access, and management.

It is important to remember that the term metadata may mean different things to different communities. The information resources found in libraries are quite different from those found in museums, historical societies, repositories of scientific data sets, or on the web. Differences in the nature, characteristics, and uses of the resources may require diverse approaches to description and to the metadata created.

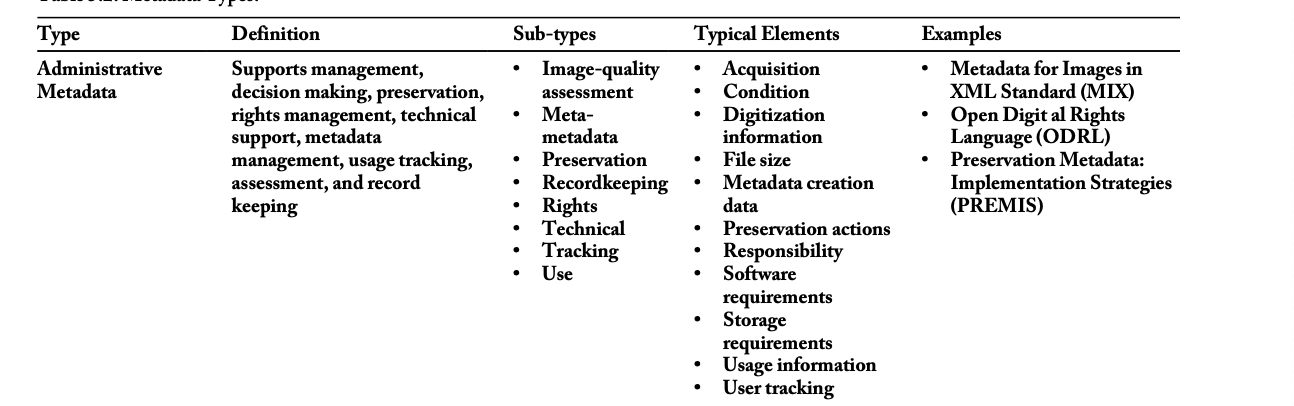

administrative metadata

created for the purposes of management, decision making, and record keeping. It provides information about the technical, preservation, and storage requirements of information resources, particularly digital objects. Administrative metadata assists with the monitoring, accessing, reproducing, digitizing, and backing up of digital resources. It includes information such as

Hardware and software requirements: creation software, creation hardware, operating system;

Acquisition information: when the resource was created, modified, and/or acquired; administrative

information about the analog source from which a digital object was derived;

Ownership, rights, permissions, legal access, and reproduction information: what rights the organization has to use the material, who may use the material and for what purposes, what reproductions exist and their current status;

Use information: what materials are used, when, in what form, and by whom; use tracking and circulation statistics; user tracking; content re-use; exhibition records;

File characteristics: file size, bit-length, format, presentation rules, sequencing information, running time, file compression information;

Version control: what versions exist and the status of the resource being described; alternate digital formats, such as HTML or PDF for text, and GIF or JPG for images;

Digitization information: compression ratios, scaling ratios, date of scan, resolution;

Authentication and security data: inhibitor, encryption, and password information; and

Preservation information: integrity information, physical condition, preservation actions, refreshing data, migrating data, conservation or repair of physical artifacts.

descriptive metadata

contains the most important identifying characteristics of an information resource and the analysis of its contents for the purposes of discovery, identification, selection, and acquisition. It includes the following kinds of information:

Identifying data: titles, statements of responsibility, dates of publication or distribution, languages, formats, resource types, identifiers;

Relationship data: creators, contributors, publishers, sources, related works, identification of other relationships among the various entities; and

Content data: subjects, abstracts, coverage, tables of contents, classification notations, and categories.

structural metadata

refers to the makeup or internal arrangement of the digital object, dataset, or other information resource that is being described. It is the data needed to ensure that a digital resource functions properly and can be used and navigated by the patron. It refers to how individual related files are bound together to create a working digital object, how the object can be displayed on a variety of systems, and how it can be stored and disseminated. It deals with what the resource is, what it does, and how it works.

captures the following kinds of information:

Document types and their structures

File types

Object behaviors or functionality

Associated search protocols

Hierarchical relationships

Sequencing and grouping of files

Parent objects

Paging information

Associated files

an be included in the headers or bodies of some types of electronic documents, but in most metadata schemas, structural elements are not well represented. For most schemas—which focus on descriptive metadata—it is simply unnecessary or inappropriate for the type of resource being represented.

basics of metadata

there are a lot of different metadata categories, and their boundaries are not fixed

has varying levels of complexity

simple format where the metadata is no more than data extracted from the resource itself

structured format: formal metadata elements sets that have been created for the general user

rich format: information professionals in libraries, archives, and museums tend to use this third level to create comprehensive, meticulously detailed descriptions; combine metadata elements with encoding and content standards

. At times, the need for such comprehensive, rich description has been questioned by those interested in developing more cost-effective approaches to metadata creation, often advocating for greater use of automatically generated metadata whenever possible. Others, however, are convinced that this will result in a reduction of the quality of the metadata produced and are opposed to making radical changes in metadata- creation processes.

can describe information resources at various levels of granularity

for individual information resource, for discrete components of those resources, or for established collections comprising multiple resource

can be found in various places and in different forms

metadata for online resource may be part of the doc itself

may be found as embedded annotations within HTML encoding

metadata elements

the individual categories or fields that hold the discrete pieces of a resource description. Typical metadata elements include title, creator, unique identifier, creation date, subject, and the like.

metadata schemas

sets of elements designed to meet the needs of particular communities. While some schemas are general in nature, most are created for specific types of information resources or for specific purposes. Specific schemas have been designed to manage government, geospatial, visual, educational, and other types of resources.

3 characteristics found in all metadata schemas

semantics

syntax

structure

semantics

refers to meaning, specifically the meaning of the various metadata elements. Semantics help metadata creators understand, for example, what the element coverage means in a given schema.

semantics of a metadata schema do not necessarily dictate the content placed into the elements. This is the province of content standards and data value standards.

syntax

refers to the encoding of the metadata. This may be the MARC format for bibliographic records or an XML schema for other types of metadata (e.g., EAD for an archives’ finding aids). Stuart Weibel writes that syntax allows us to “take a set of metadata assertions and pack them so that one machine can send them to another, where they can be unpacked and parsed. . . . Syntax is arranging the bits reliably so they travel comfortably between computers.”

structure

refers to the data model used to shape the way that metadata statements are expressed. Weibel states, “structure is the specification of the details necessary to layout [sic] and declare metadata assertions so they can be embedded unambiguously in a syntax. A data model is the specification of this structure.”

content standards

used to dictate things such as how dates will be formatted within metadata elements or how a personal name will be entered. For example, a set of best practices guidelines might state that all dates are to be recorded using the YYYY-MM- DD format; or a content standard may require personal names to be entered with family name first, followed by a comma, and then by the remainder of the name.

metadata characteristics

interoperability

flexibility

extensibility

interoperability

the ability of various systems to interact with each other no matter the hardware or software being used.

Achieving interoperability helps to minimize the loss of information due to technological differences. Interoperability can be divided into semantic, syntactic, and structural interoperability.

semantic: ways in which diverse metadata schemas express meaning in their elements. In other words, does the element author in one schema mean exactly or nearly the same thing as creator in another?

syntactic: the ability to exchange and use metadata from other systems. Syntactic interoperability requires a common encoding format (e.g., Can a MARC record be used and understood in an XML environment?

structural: how metadata statements are expressed. Is the metadata understandable by other systems? Are both systems using an entity-relationship model or are the basic structures different? Without interoperability on all three levels, metadata cannot be shared effortlessly, efficiently, or profitably.

flexibility

the ability of “metadata creators to include as much or as little detail as desired in the metadata record, with or without adherence to any specific cataloging rules or authoritative lists.

extensibility

the ability to use additional metadata elements and qualifiers (i.e., element refinements) to meet the specific needs of various communities. Qualifiers help to refine or sharpen the focus of an element or might identify a specific controlled vocabulary to be used in that element (e.g., the element title could have a qualifier to specify subtitle, alternative title, earlier title, or another variant form). An example of extensibility can be found in the education community. In order to meet their specific needs, a standard element set was extended by adding instructional method and audience as elements.

Note: extensibility and interoperability have an inverse relationship; as extensibility increases, interoperability can decrease because as the schema moves further away from its original design, it becomes less understandable to other systems using the base schema

technical metadata

an subcategory of administrative metadata

describes the physical rather than intellectual characteristics of digital objects.”15 Basic technical information is needed in order to understand the nature of the resource, the software and hardware environments in which it was created, and what is needed to make the resource accessible to users. Technical metadata describes the characteristics, origins, and lifecycles of digital documents, and is key to the preservation of the resource for future use.

preservation metadata

subcategory of administrative metadata

the information needed to ensure the long-term storage and usability of digital content. It may include information about reformatting, migration, emulation, conservation, file integrity, and provenance. Typical preservation metadata elements might include the following:

identifiers

structural types

file descriptions

sizes

properties

software and hardware environments

source information

object history

transformation history

context information

digital signatures

checksums

rights and access metadata

subcategory of administrative metadata

information about who has access to information resources, who may use them, and for what purposes. It deals with issues of creators’ intellectual property rights and the legal agreements allowing users to access this information. It addresses questions such as: Who can access an information resource and for what purposes? Who can make copies? Who owns the material? Are there different categories of information objects in the collection? Are there different categories of users who can access different combinations of those objects?

Access categories

Identifiers

Names of creators

Names of rights holders

Dates of creation

Copyright status

Terms and conditions

Access restrictions

Periods of availability

Usage information

Payment options

meta-metadata

subcategory of administrative metadata

metadata track administrative data about a resource, but it can also track administrative information about its metadata. So, if metadata is “data about data,” then the “data about the data about data” is meta-metadata. Meta-metadata is important for ensuring the authenticity of the metadata and tracking internal processes.

page-turner model

a successful implementation of structural metadata

used for materials with a defined internal structure and content that is meant to be viewed in a prescribed sequence (e.g., an e- book). It provides structure for the contents to be displayed and for the user to navigate through the information resource as one normally pages through a book. The page-turner may allow the user to navigate through the resource on more than one level, that is, at a chapter level and at a page level. The page-turner uses structural metadata to bind together individual images of pages to form a complete object (again, this may be on the level of an e-book, a volume of a set, or a chapter). It may also use structural metadata to associate a text file with each image of individual pages, so that the intellectual contents of the page image are searchable.

METS

Metadata Encoding and Transmission Standard

one of the best examples of structural metadata

an XML schema for encoding structurally complex digital objects into a single document that includes descriptive, administrative, and structural metadata.

provides metadata aimed at managing, preserving, displaying, and exchanging digital objects in a digital library environment. Although descriptive and administrative metadata are included in METS documents, the primary focus of the schema is on the structure of digital objects. It is extensible and modular in its approach.

A METS document comprises seven components.

METS header: contains meta-metadata such as the creator and the creation date of the METS document.

Descriptive metadata: allows the creators to choose from a number of extension schemas, including Marc, mods,ead, Dublin Core, vra, tea, ddi

Administrative metadata: can be divided into four subgroupings: technical, intellectual property rights, source, and digital provenance metadata. For these areas, PREMIS, AudioMD Schema, VideoMD Schema, and MIX have been endorsed as extension schemas that may be used to complete the section.

File section: an inventory of all the files used to create the digital object. Files may be divided into hierarchically subordinate groups.

Structural map: specifies the ways in which all the files fit together to create the digital object. The map is hierarchically structured and allows the user to navigate from one part of the digital object to another (e.g., from track one to track five on a digitized sound recording).

Structural links: keeps a record of the hyperlinks and lateral relationships among individual files in the structural map.

Behavior metadata: describes how the object is to function or perform.

What are some metadata management tools?

application profiles

metadata registries

crosswalks

application profiles

a mechanism to allow metadata creators to use various elements from different schemas

a formally developed specification that limits and clarifies the use of a metadata schema for a particular user community.

Application profiles, therefore, are documents that describe a community’s recommended best practices for metadata creation. They contain policies, guidelines, and metadata elements drawn from one or more namespaces.

namespace: a formal collection of element types and attribute names; the authoritative place for information about the metadata schema that is maintained there; allows metadata elements to be unambiguously identified and used across communities- promotes semantic interoperability

a formal way to declare which elements from which namespaces are used in a particular application or project or by a particular community

do not create or introduce new metadata elements; they mix and match existing elements from various schemas if one schema is not sufficient (141)

metadata registries

A registry is a database used to organize, store, manage, and share metadata schemas.

provide information about schemas and their elements, controlled vocabularies, application profiles, definitions, and relationships, using a standard structure as outlined in ISO/IEC 11179–3:2013, “Information Technology–Metadata Registries (MDR)—

once they become more widely implemented, will help greatly to improve interoperability among metadata schemas.

few registries exist at this time

crosswalks

tool used to achieve semantic interoperability

needed so that users and creators understand equivalence relationships among metadata elements in different communities.

help us see that the 100 field in a MARC record for the primary creator is roughly equivalent to the creator field in a Dublin Core record

a specification for mapping one metadata standard to another. Crosswalks provide the ability to make the contents of elements defined in one metadata standard available to communities using related metadata standards.

creation of these is difficult and susceptible to error; person needs expertise in each metadata schema included in the crosswalk

the element-mapping process is particularly difficult

the conversion process, via crosswalks, from one schema to another lacks precision. Few metadata crosswalks provide round-trip conversion with no loss of data. Some data are lost in one direction or the other (or both).

metadata models

a description of observed or predicted behaviour of some system, simplified by ignoring certain details. Models allow complex systems, both existent and merely specified, to be understood and their behaviour predicted

a description or analogy used to help visualize something . . . that cannot be directly observed

how different communities are attempting to provide a shared understanding of resource description within their community

(143)

IFLA’s FRBR model

attempts to apply an entity-relationship model (E-R model) to various components of the bibliographic universe

an abstract conceptual model

enumerates the entities found in the bibliographic universe and gathers those entities into groups based on the functions or roles of those entities.

identifies the attributes or characteristics associated with each entity, as well as relationships that exist among and within the entity groups

identifies user tasks (tasks that users perform while using information retrieval tools and interacting with bibliographic data)

maps each entity’s attributes and its relationships to the user tasks, which allows catalogers to see the significance of each element in a bibliographic description.

identifies 4 user tasks, 3 groups of entities, and a myriad of attributes and relationships among the entities

IFLA’s FRAD and FRSAD

FRAD

an attempt at modeling the bibliographic universe, but doesn’t focus on bibliographic records; focuses on authority data and the concepts related to authority control

an extension of the FRBR model, adding more entities, attributes, relationships, and user tasks

includes another type of user in its model- metadata creators

user tasks

to find (same as FRBR)

to identify (same as FRBR)

to contextualize:to place a person, corporate body, work, etc., in context; clarify the relationship between two or more persons, corporate bodies, works, etc.

to justify: documenting acceptable reasons for the choice of the forms of names or titles as the preferred forms.

has identified 5 additional entities outside of FRBR that are specifically related to authority data

name, identifier, controlled access point, rules, agency

FRSAD

a high-level conceptual model of the subject relationships existing in the bibliographic universe

identifies additional entities, relationships, and user tasks.

four sets of users (general end-users; information professionals who create and maintain metadata; those who create and maintain subject authority data; reference librarians and other professionals who search on behalf of general end users)

user tasks

to find

to identify

to select

to explore: exploring “relationships among terms during cataloguing and metadata creation,” as well as exploring “relationships while searching for bibliographic resources.

has 2 additional entities outside of FRBR

thema: any type of subject matter (e.g. topic, time period, work)

nomen: refers to that thing’s name or label