UNC BIOL253 Evaluation 2 Study Guide

1/86

Earn XP

Description and Tags

Content on cell membranes, diffusion, osmosis, membrane potentials, and neurophysiology

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

87 Terms

Functions of plasma membranes

Regulate the passage of substances into and out of cells and between cell organelles and cytosol

Detect chemical messengers arriving at the cell surface

Link adjacent cells together by membrane junctions

Anchor cells to the extracellular matrix

Structure of plasma membrane

made of phospholipid bilayer with embedded proteins (amphipathic integral or transmembrane proteins) and peripheral proteins (along surfaces of the membrane)

Glycerol

Fatty acids

Phosphate groups

Phospholipids

Proteins

Cholesterol

Fluid-mosaic model

concept of proteins freely moving about in the lipid bilayer of plasma membrane

Amphipathic

a molecule that has both a hydrophilic (water-loving/polar/charged) region, and a hydrophobic (water-repelling/nonpolar) region within the same molecule

spontaneously arrange themselves in water so that hydrophilic parts face water, and hydrophobic parts avoid water

Ex. phospholipids

Transmembrane proteins (integrins)

Proteins that span the entire plasma membrane → part of the protein is inside the cell, while part is embedded inside the lipid bilayer, and another part extends outside the cell

Extracellular matrix (ECM)

A network of proteins and carbohydrates outside cells that provides structural support and biochemical signals to tissues

The role of integrins binding to the extracellular matrix

Physical attachment: They form a mechanical link between the ECM and the cell interior (this is how cells stay anchored in tissues)

Signal transduction (outside ←→ inside): integrins change shape and trigger intracellular signaling pathways for cells to receive information about mechanical stress, ECM composition, and tissues

Cell junctions

How are cells packed together into tissue/organ types and how do they interact with neighboring cells/tissue?

Cells pack together using junctions, ECM, and membrane proteins

Interactions occur through:

Direct contact

Chemical signals

Mechanical forces

The structure of the tissue reflects its function

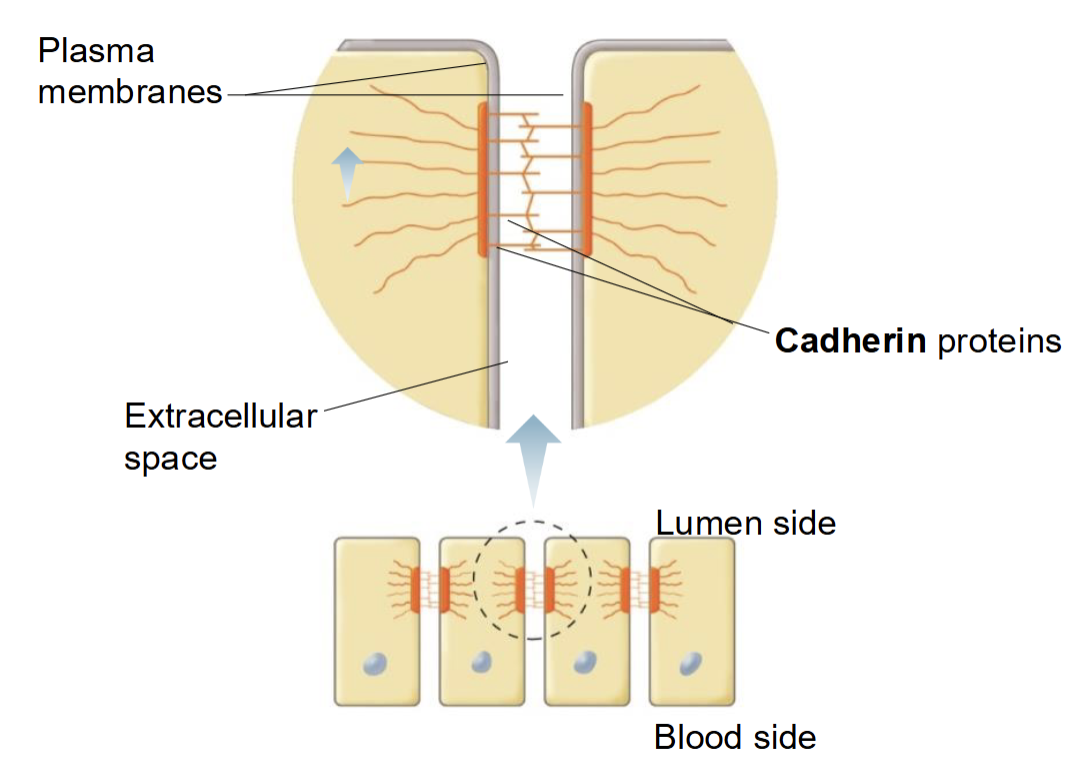

Desmosomes (anchoring junction)

Dense plaques (accumulated proteins), Cadherin proteins join plasma membranes of adjacent cells together, found in tissue subject to considerable stretching

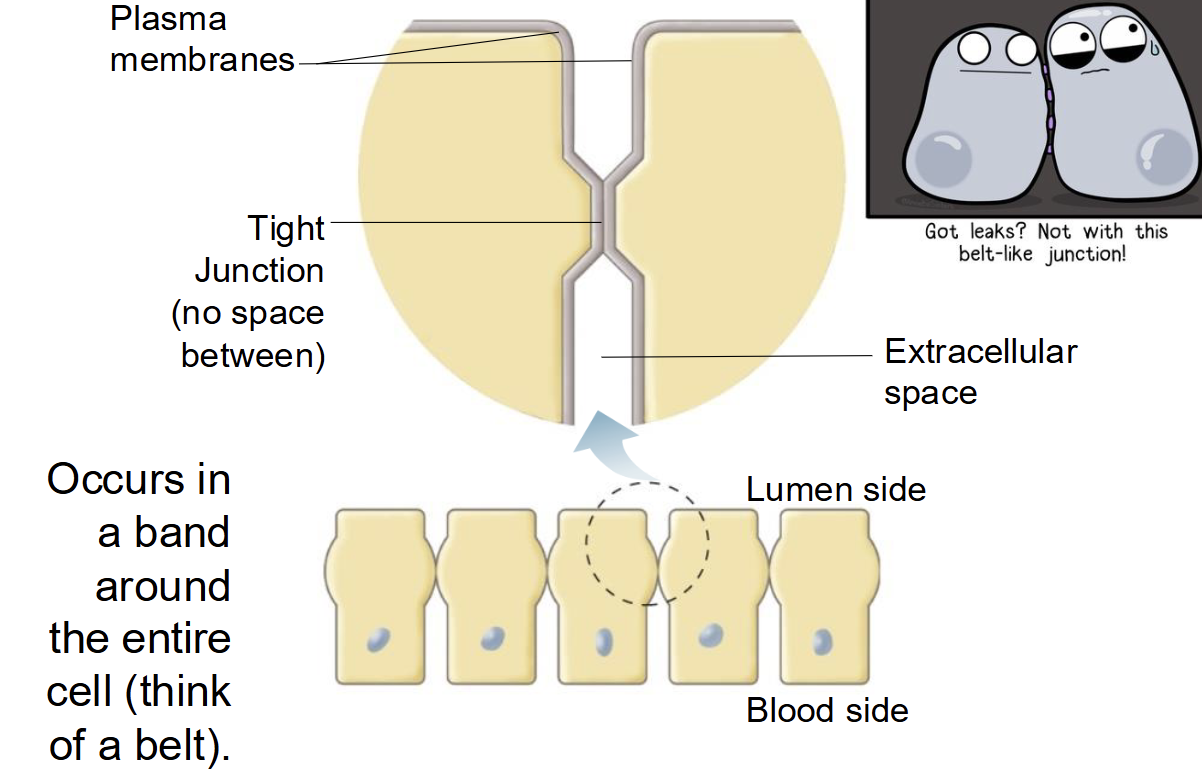

Tight junction (occluding junction)

no space in between adjacent cells, occurs in a band around the entire cell (think like a belt), found in most epithelial cells, prevents paracellular movement of substances

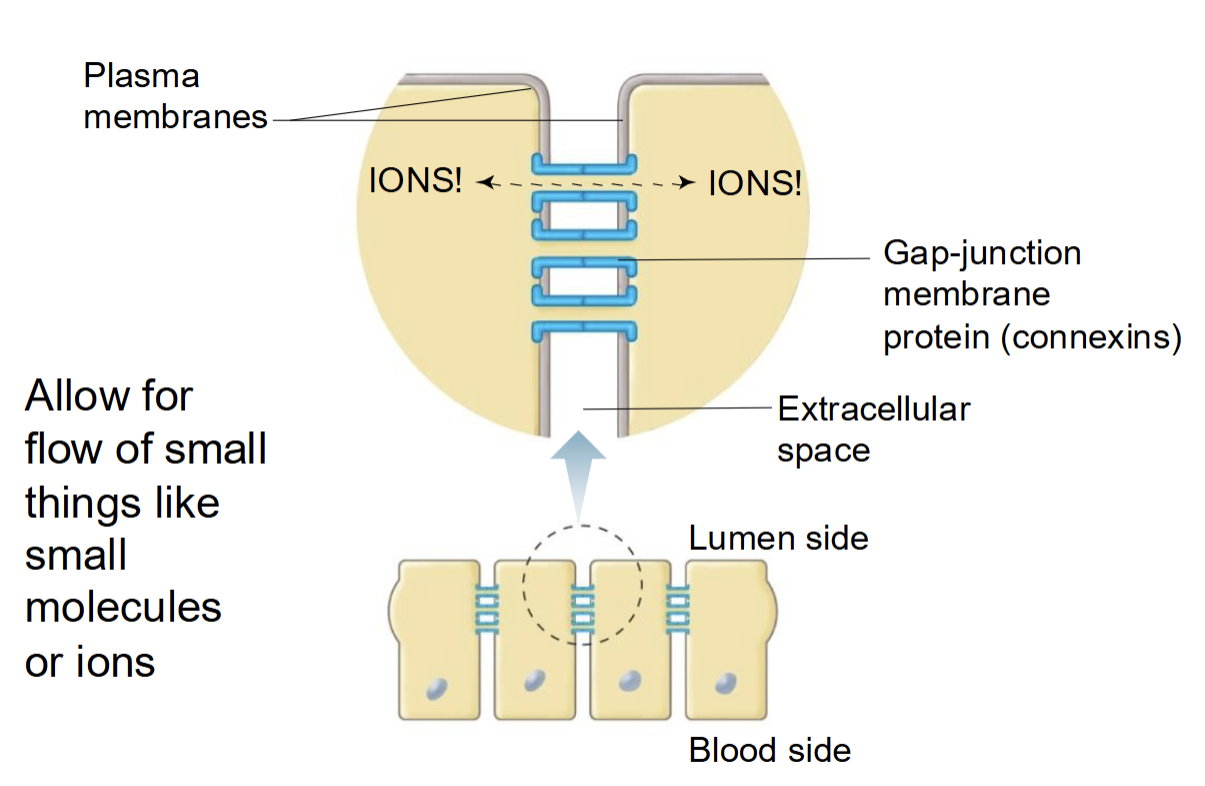

Gap junction (communicating junction)

membrane proteins called connexins join cells together, allows for flow of small things like ions or small molecules, helps with electrical signal flow

Occluding junctions

seal cells together in an epithelium (prevents small molecules from leaking from one side to the other)

Anchoring junctions

mechanically attach cells (and their cytoskeleton) to their neighbors or the extracellular matrix

Communicating junctions

mediate passage of chemical or electrical signals from one interacting cell to its neighbor

How fast does plasma membrane turnover happen?

In minutes to hours

Factors that influence the rate of diffusion

Concentration gradient

Distance (path length) → thicker membranes or tissues slow diffusion down

Surface area → greater surface area = faster diffusion

Molecule size (molecular weight) → smaller molecules diffuse faster than larger ones

Temperature → high temperature = more kinetic energy = faster diffusion

Medium → diffusion is fastest in gases, slower in liquids, and slowest in solids

Membrane permeability

Electrical gradient (for ions)

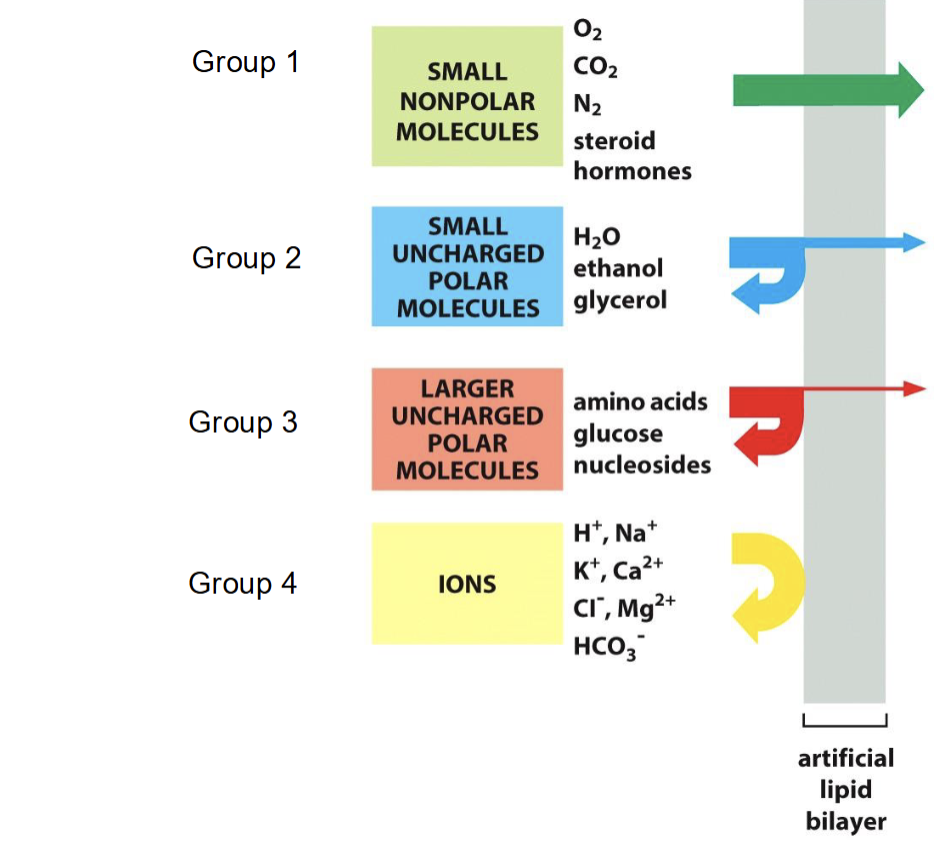

What type of ions freely pass through the phospholipid bilayer?

Freely: small, nonpolar molecules (O2, CO2, N2, steroid hormones)

Group 2: small, uncharged polar molecules (water, ethanol, glycerol)

Group 3: larger, uncharged polar molecules (amino acids, glucose, nucleosides)

Group 4: Ions (H+, Na+, K+, Ca2+, Cl-, Mg2+, HCO3-)

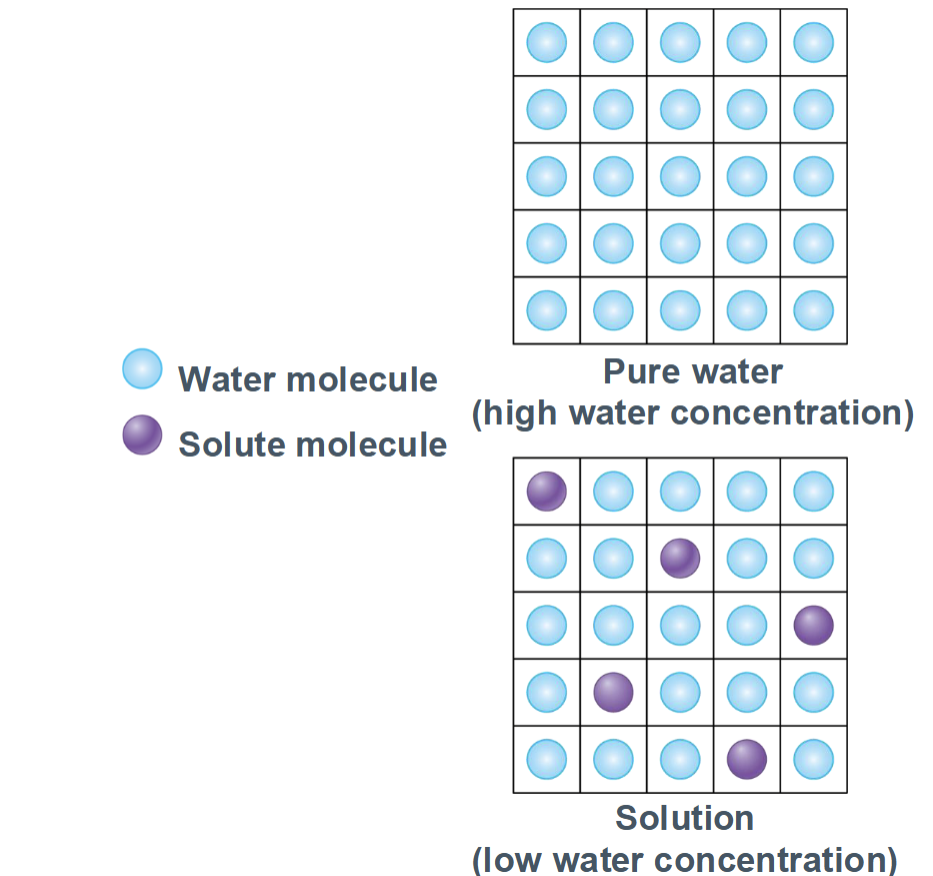

Osmosis

net diffusion of water

Osmolarity

total solute concentration of a solution

Membrane permeability vs. osmotic pressure

Only solutes that cannot cross the membrane create lasting osmotic pressure

depends on the number of non-penetrating solutes and the membrane permeability to those solutes

Membrane permeability vs. volume changes

Occurs when a membrane is permeable to water but not solutes

solutes are trapped on one side

Water moves towards higher solute concentration

Causes cell to shrink (hypertonic) or swell (hypotonic)

Occurs when a membrane is permeable to some solutes

Permeable solutes diffuse across the membrane

Osmotic pressure decreases as solute concentrations equalize

Penetrating solutes do not sustain osmotic pressure

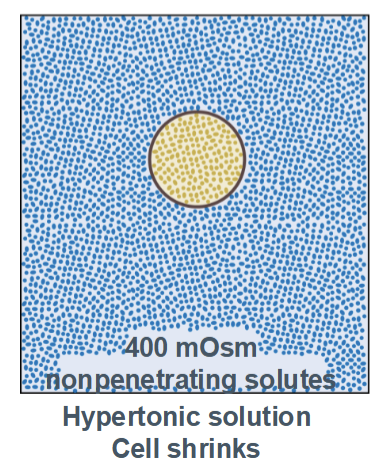

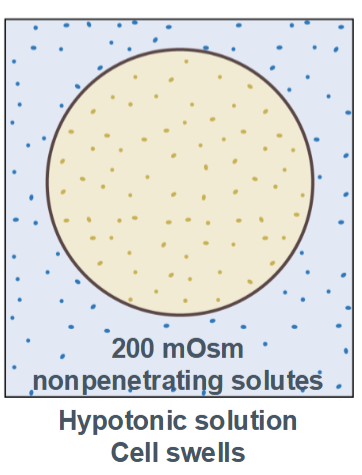

Tonicity

he ability of a solution to change the volume of a cell by causing water to move across a semipermeable membrane

depends only on non-penetrating (impermeable) solutes

describes the effect on cell volume, not just solute concentration

Types include isotonic, hypertonic, and hypotonic

Isotonic

no change in the cell volume (equal concentrations outside and inside the cell)

Hypertonic

cell shrinks (higher concentration in the environment than inside the cell)

Hypotonic

cell swells with water (higher concentration inside the cell than in the environment)

Examples of osmosis in healthcare

IVs, kidney function, dialysis, digestion/nutrition, eye care, diuretics

Membrane potential

The electrical voltage difference across a cell’s plasma membrane, caused by an unequal distribution of charged ions between the inside and outside of the cell

Measured in millivolts (mV)

The inside of the cell is usually negative relative to the outside

Typical resting membrane potential: neurons ~ -70mV, muscle cells ~ -90mV

Membrane permeability to specific ions

At rest, membranes are most permeable to K⁺

K⁺ leaks out through leak channels → inside becomes negative

Opening or closing ion channels changes permeability and membrane potential

Examples:

↑ Na⁺ permeability → depolarization

↑ K⁺ permeability → hyperpolarization

↑ Cl⁻ permeability → stabilizes or hyperpolarizes membrane

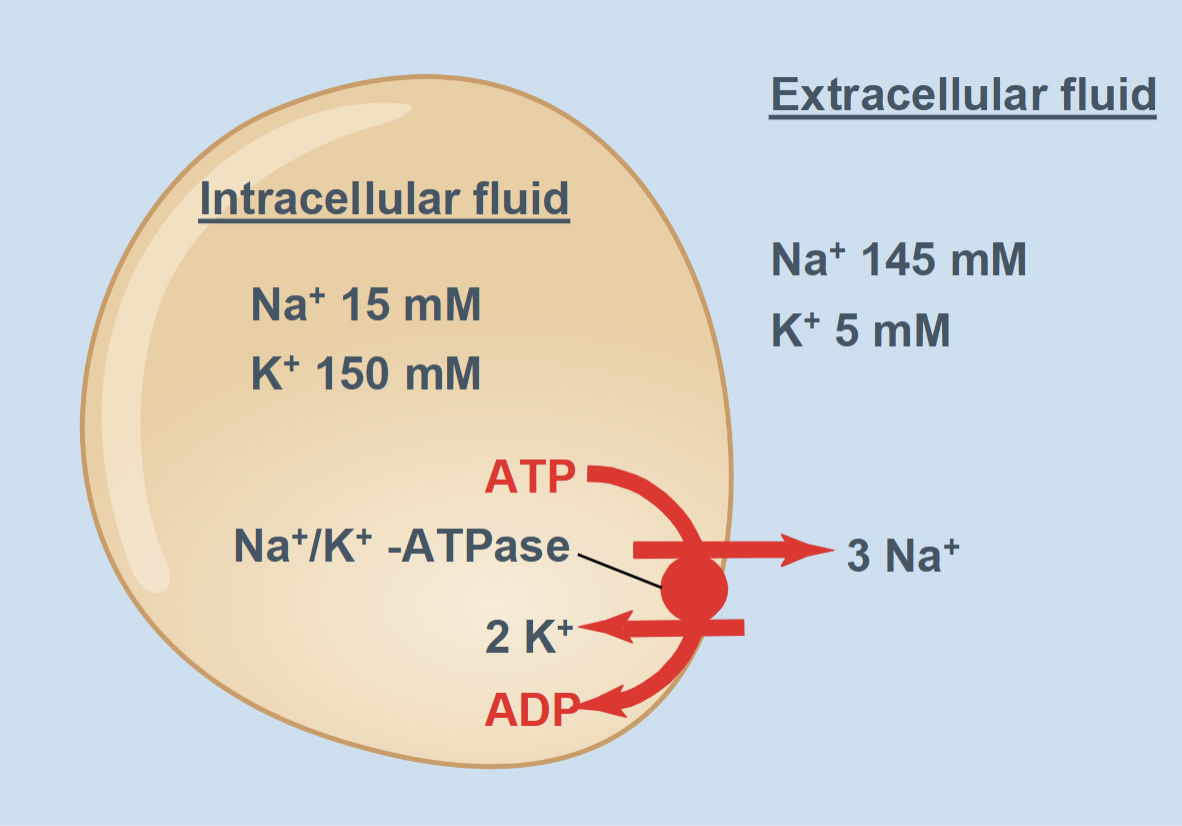

Electrogenic pump (Na+/K+-ATPase)

Moves 3 Na+ out and 2 K+ in, creates and maintains ion gradients, and slightly contributes to negativity inside the cell

What are the two driving forces of the cellular electrochemical gradient?

Concentration gradient: difference in ion concentration across the membrane, ions move from high to low concentration

Electrical gradient: difference in electrical charge across the membrane, ions move toward opposite charges

Why might an H+-ATPase (proton pump) be useful in cells?

actively transports protons (H⁺) across a membrane using energy from ATP, creating proton gradients that the cell can use for multiple vital functions

Generating an electrochemical gradient: Pumps H⁺ out of the cytoplasm

Driving secondary transport: The proton gradient can be used to drive the transport of other molecules against their concentration gradient

H⁺ moving back down its gradient can co-transport nutrients (e.g., glucose, amino acids)

Maintaining intracellular pH: Pumps H⁺ out of the cytoplasm to prevent acidification and keeps enzyme function and metabolism optimal

Why might an H+/K+-ATPase be found in acid secreting cells of the stomach?

it actively pumps protons (H⁺) into the stomach lumen in exchange for potassium (K⁺), creating the highly acidic environment needed for digestion

Mediated transport

the movement of molecules across a cell membrane with the help of specific proteins, because the molecules are too large, charged, or polar to diffuse freely through the lipid bilayer

Facilitated diffusion

Direction: Down the concentration gradient (no energy required)

Proteins involved: Carrier proteins or channels

Examples and tissue specialization:

Glucose transporters (GLUTs) in muscle and liver → allow glucose to enter cells when blood glucose is high

Selective and faster than simple diffusion, but cannot move against a gradient

Primary active transport

Direction: Against the concentration gradient (requires energy from ATP)

Proteins involved: Pumps (ATPases)

Examples and tissue specialization:

Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase in all cells → maintains resting membrane potential and osmotic balance

H⁺/K⁺-ATPase in stomach parietal cells → secretes acid for digestion

Generates ion gradients used for signaling, volume control, and secondary transport

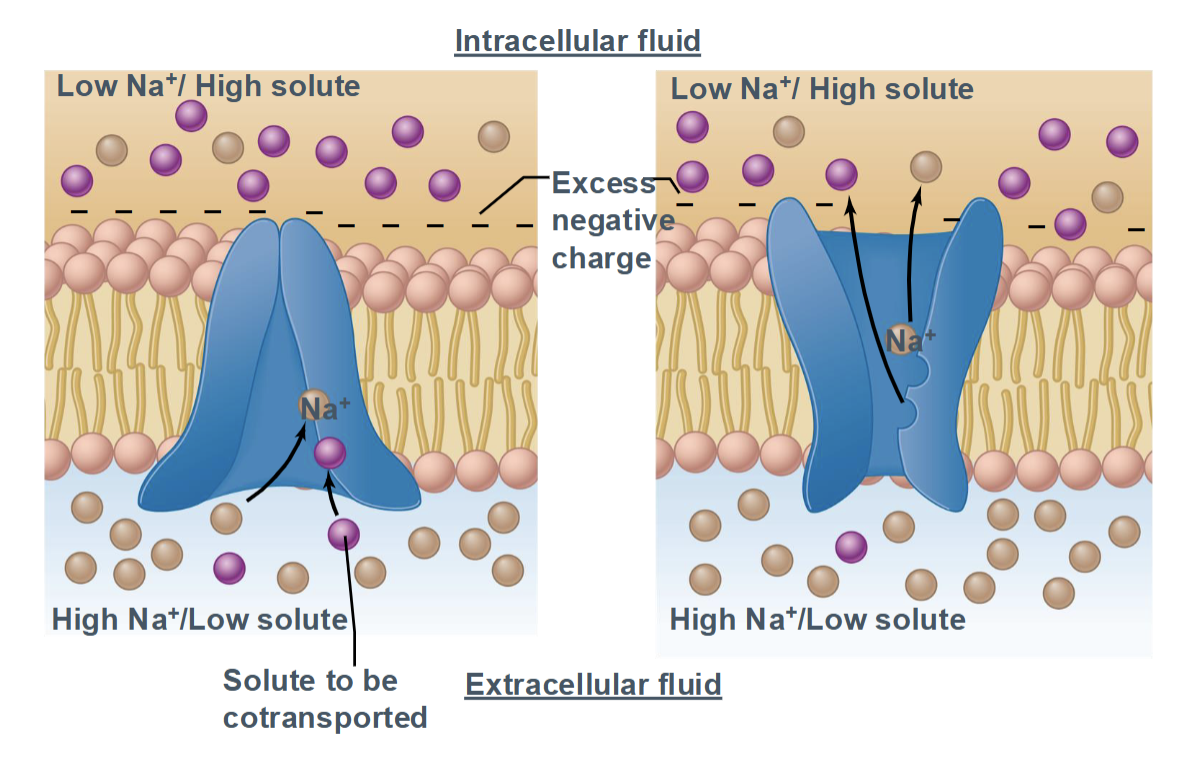

Secondary active transport

Direction: Uses the gradient of one molecule to drive movement of another

Proteins involved: Symporters or antiporters

Examples and tissue specialization:

SGLT (sodium–glucose cotransporter) in kidney and intestine → uses Na⁺ gradient to absorb glucose

Na⁺/Ca²⁺ exchanger in cardiac muscle → removes calcium for muscle relaxation

Relies on gradients established by primary active transport; efficient for nutrient absorption and ion homeostasis

Fanconi-Bickel Syndrome

No underlying enzymatic defect in carbohydrate metabolism had been identified, metabolism of both glucose and galactose is impaired, effects GLUT2 deficiency (SLC2A2 mutation), glycogen storage disease

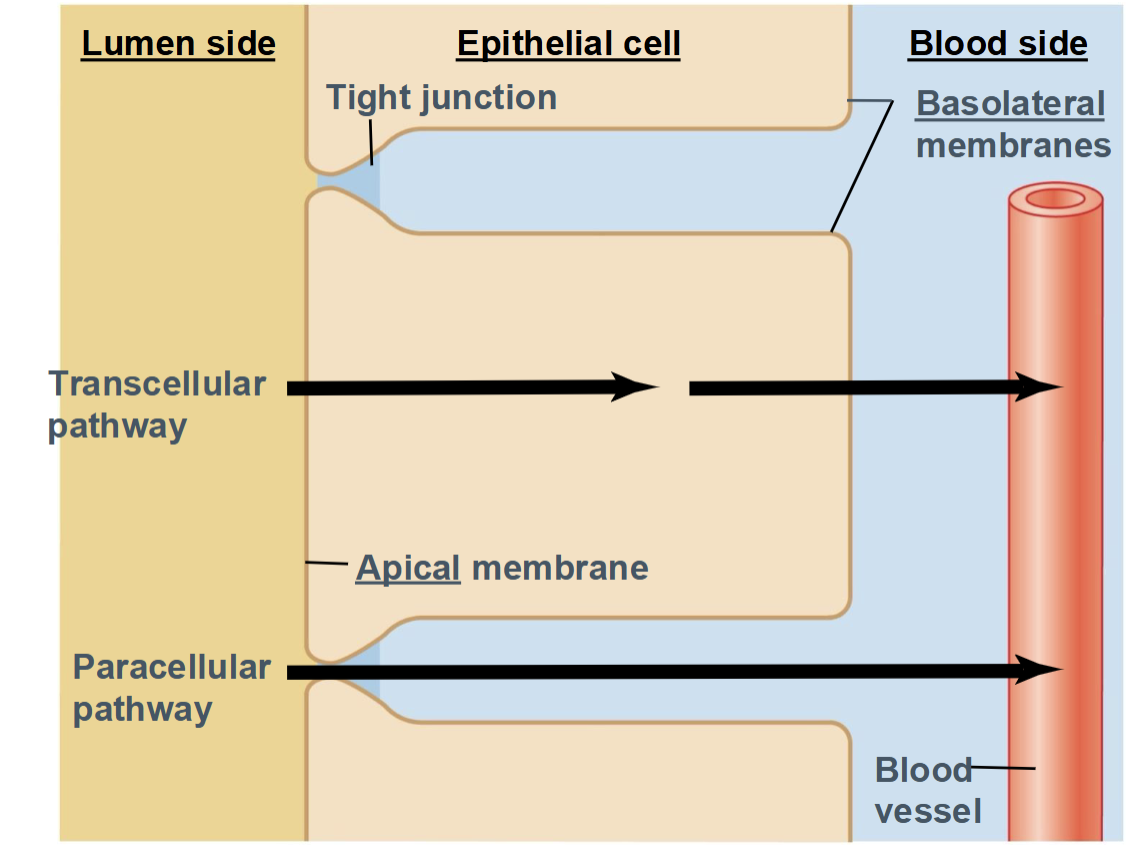

Epithelial transport

the movement of substances across an epithelial cell layer, from one side of the tissue to the other (for example, from the intestinal lumen into the blood)

Transcellular pathway

Paracellular pathway

Transcellular pathway

Substance moves through the epithelial cells

Uses channels, carriers, and pumps

Highly selective and regulated

Paracellular pathway

Substance moves between cells

Passes through tight junctions

Usually limited to small ions or water

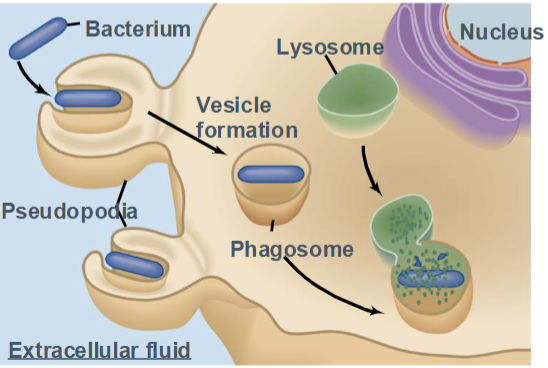

Phagocytosis

a form of endocytosis in which specialized cells engulf large particles, such as bacteria, dead cells, or debris.

Known as “cell eating”

Performed mainly by immune cells (macrophages, neutrophils)

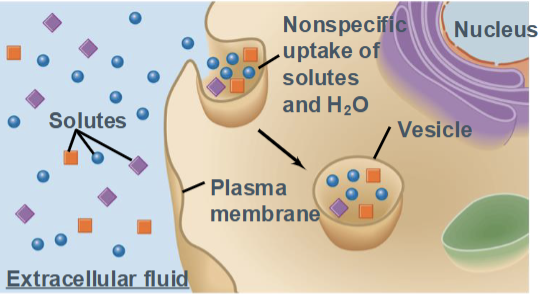

Pinocytosis

a form of endocytosis in which a cell nonspecifically engulfs extracellular fluid and dissolved solutes into small vesicles.

Often called “cell drinking”

Occurs continuously in most cells

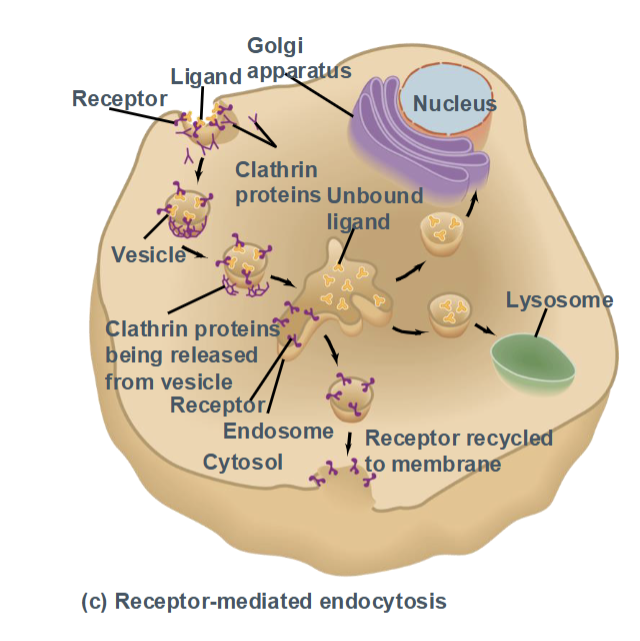

Receptor-mediated endocytosis

a highly specific form of endocytosis in which ligands bind to cell-surface receptors, triggering vesicle formation.

Uses clathrin-coated pits

Allows efficient uptake of specific molecules (e.g., LDL cholesterol, hormone

Exocytosis

the process by which a cell releases substances to the outside by fusion of an intracellular vesicle with the plasma membrane.

Used to secrete hormones, neurotransmitters, enzymes, and membrane proteins

Can be constitutive (continuous) or regulated (stored then released)

Endocytosis

the process by which a cell brings substances into the cell by forming a vesicle from the plasma membrane.

Requires energy

Includes:

Pinocytosis

Phagocytosis

Receptor-mediated endocytosis

Trogocytosis

a process in which a cell extracts and internalizes small pieces of another cell’s plasma membrane during direct cell–cell contact.

Common in immune cells (T cells, NK cells)

Allows rapid cell-to-cell communication and signaling modulation

Apical membrane

faces fluid cavities, body surfaces

Basolateral membrane

lateral surfaces face other epithelial cells; basal cells face connective tissues

Volts (V)

difference in charge across a membrane

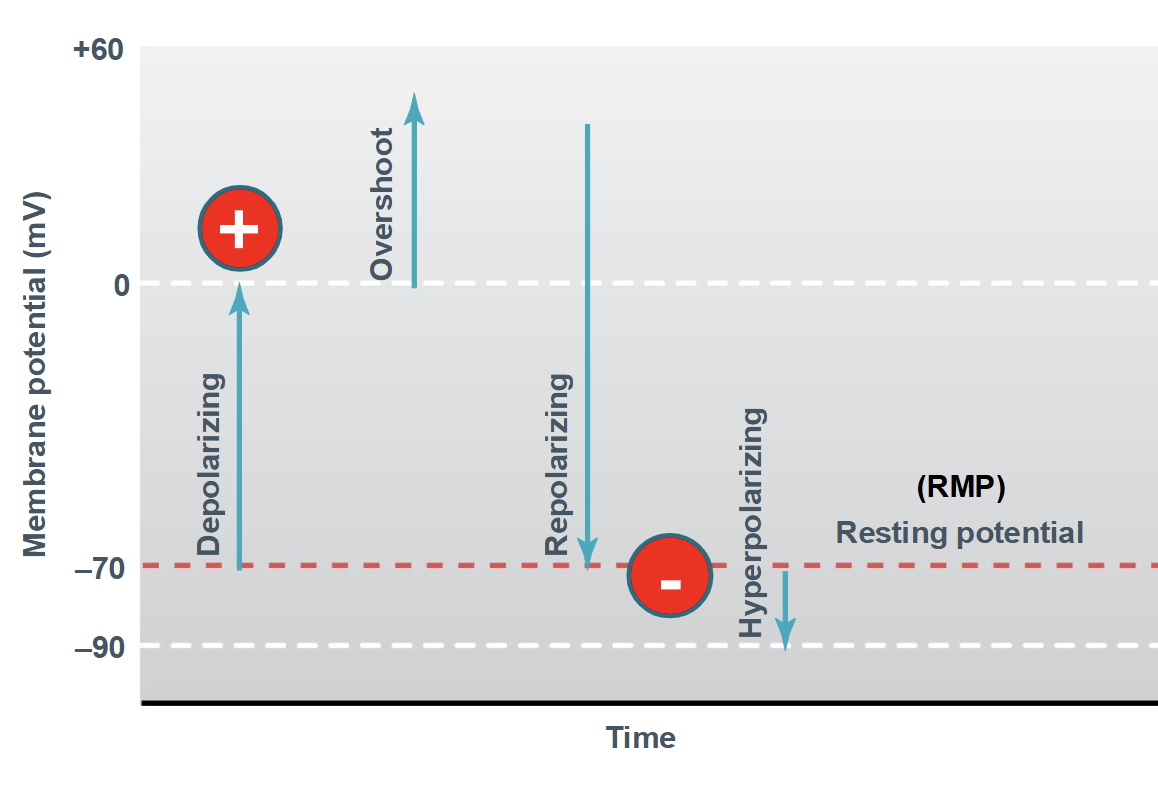

Resting membrane potential

the stable electrical voltage across the plasma membrane of a non-signaling cell, with the inside of the cell being negative relative to the outside.

Typical values:

Neurons: ~ −70 mV

Muscle cells: ~ −90 mV

How resting membrane potential is maintained

1. Unequal ion distribution

Na⁺: high outside, low inside

K⁺: high inside, low outside

Cl⁻: high outside

Negatively charged proteins trapped inside the cell. These gradients create a tendency for ions to move.

2. Selective membrane permeability

At rest, the membrane is most permeable to K⁺

K⁺ leaks out through K⁺ leak channels

Loss of positive charge leaves the inside negative

Electrical forces balance diffusion

As K⁺ leaves, the interior becomes negative

Electrical attraction pulls K⁺ back in

Equilibrium between chemical and electrical forces stabilizes the voltage

Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase (ion pump)

Pumps 3 Na⁺ out and 2 K⁺ in using ATP

Maintains ion gradients

Slightly increases the negative charge inside the cell

Membrane potential (Vₘ)

the electrical voltage difference across the plasma membrane, resulting from unequal distribution of ions and selective membrane permeability.

Expressed in millivolts (mV)

Inside of the cell is typically negative relative to the outside

Equilibrium potential

the membrane voltage at which there is no net movement of a specific ion across the membrane, because the electrical force exactly balances the chemical (concentration) gradient for that ion.

Each ion has its own equilibrium potential (e.g., Eₖ, Eₙₐ)

Calculated using the Nernst equation

Electrogenic pump

a membrane transport protein that moves unequal numbers of charges across the membrane, directly contributing to the membrane potential.

Requires ATP

Example: Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase (3 Na⁺ out, 2 K⁺ in)

How does the Na/K pump contribute to the membrane potential?

It established the concentration gradient and creates a small negative potential

Greater net movement of K+ out makes membrane more negative inside the cell

Steady negative resting membrane potential, ion flux through channels balances each other

Overshoot

peak of positive potential (depolarization above 0 mV)

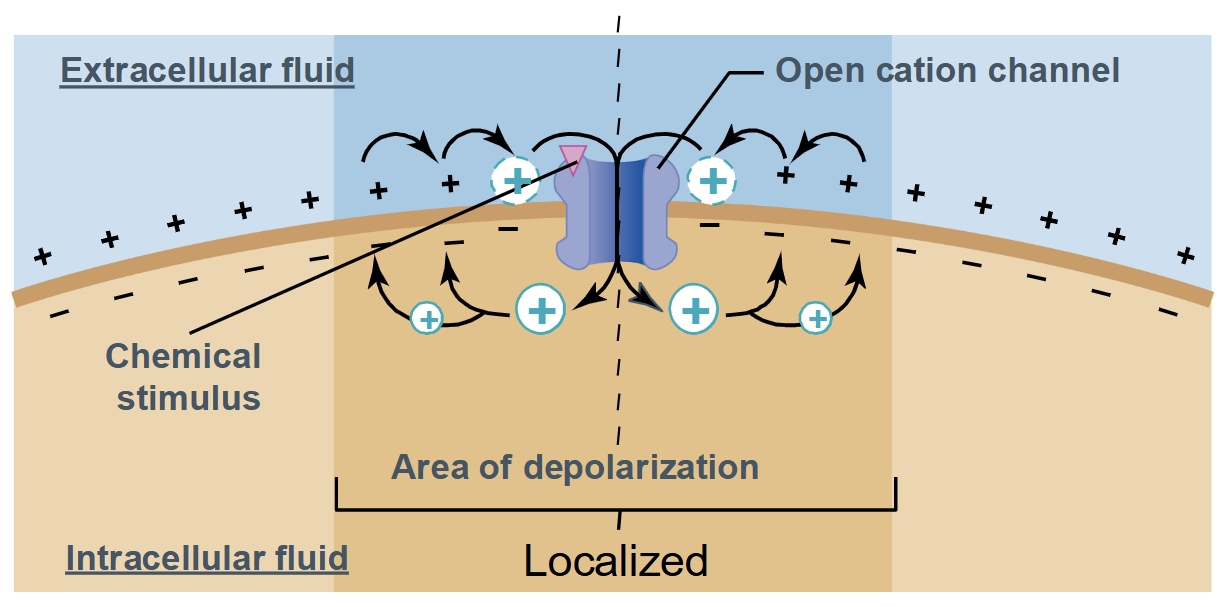

Graded potentials

Occurs in a small region of the plasma membrane (localized)

Magnitude can vary

Decremental signals → become weaker as they get further from the origin

No threshold and no refractory period

Action Potentials

Large alterations in membrane potential

Rapid and repeating

Long-distance cell communication

Voltage-gated ion channels

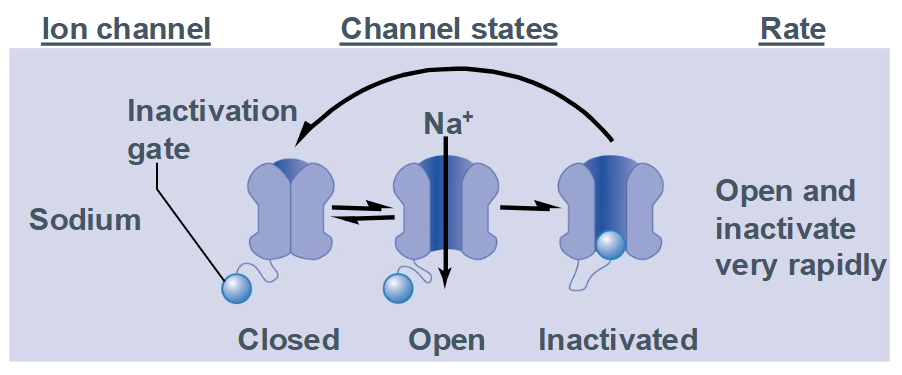

Characteristics of Na+ Channels

Channel has 3 states:

closed (resting)

open

inactivated (open but inactivation gate is blocking the channel)

Opens and inactivates very rapidly

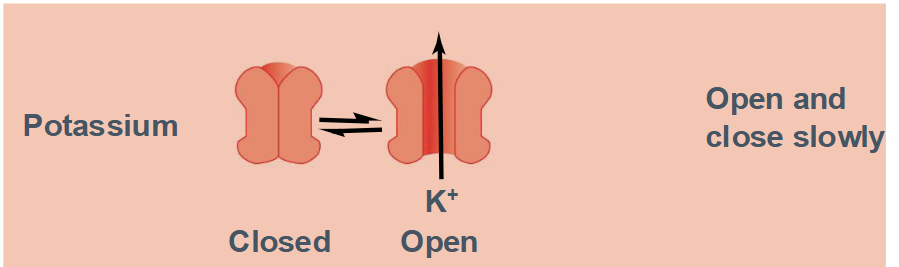

Characteristics of K+ Channels

Channel has 2 states:

Open

Closed

Opens and closes slowly

Steps of an Action Potential

Steady resting membrane potential is near Ek, Pk > PNa, due to leak K+ channels

Local membrane is brought to threshold voltage by a depolarizing stimulus

Current through opening voltage-gated Na+ channels rapidly depolarizes the membrane, causing more Na+ channels to open

Inactivation of Na+ channels and delayed opening of voltage-gated K+ channels halt membrane depolarization

Outward current through open voltage-gated K+ channels repolarizes the membrane back to a negative potential

Persistent current through slowly closing voltage-gated K+ channels hyperpolarizes membrane toward Ek; Na+ channels return from inactivated state to closed state (without opening)

Closure of voltage-gated K+ channels returns the membrane potential to its resting value

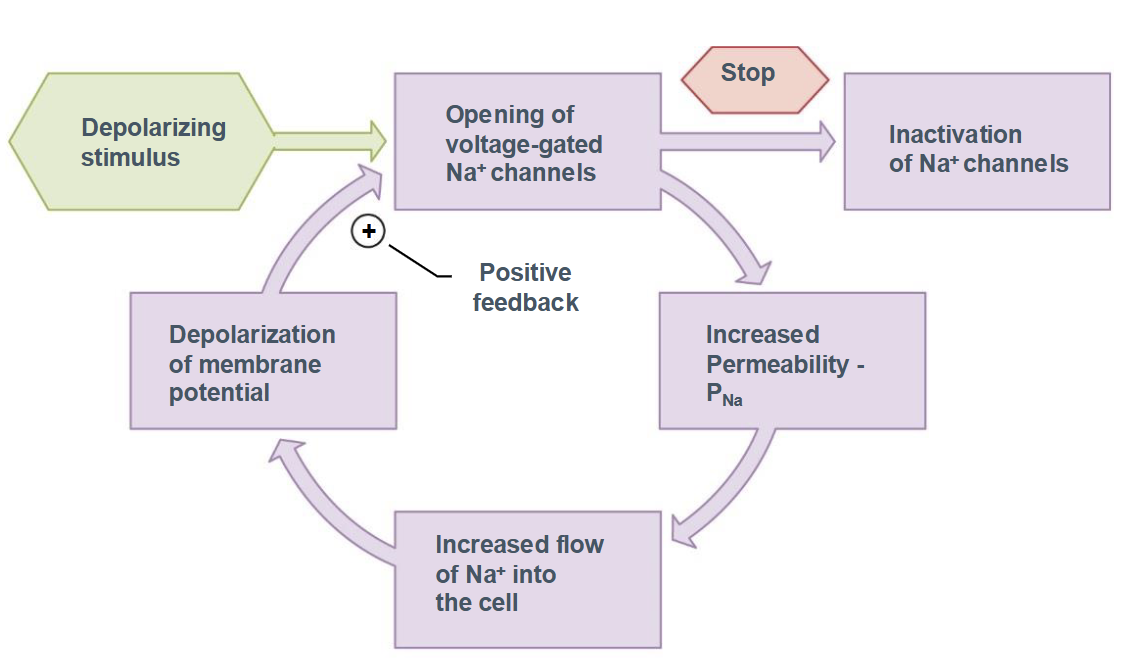

Function of Sodium Ion Channels

Depolarizing stimulus

Opening of voltage-gated Na+ channels

Increased permeability of PNa

Increased flow of Na+ into the cell

Depolarization of the membrane potential leads to positive feedback loop

Eventual inactivation of Na+ channels

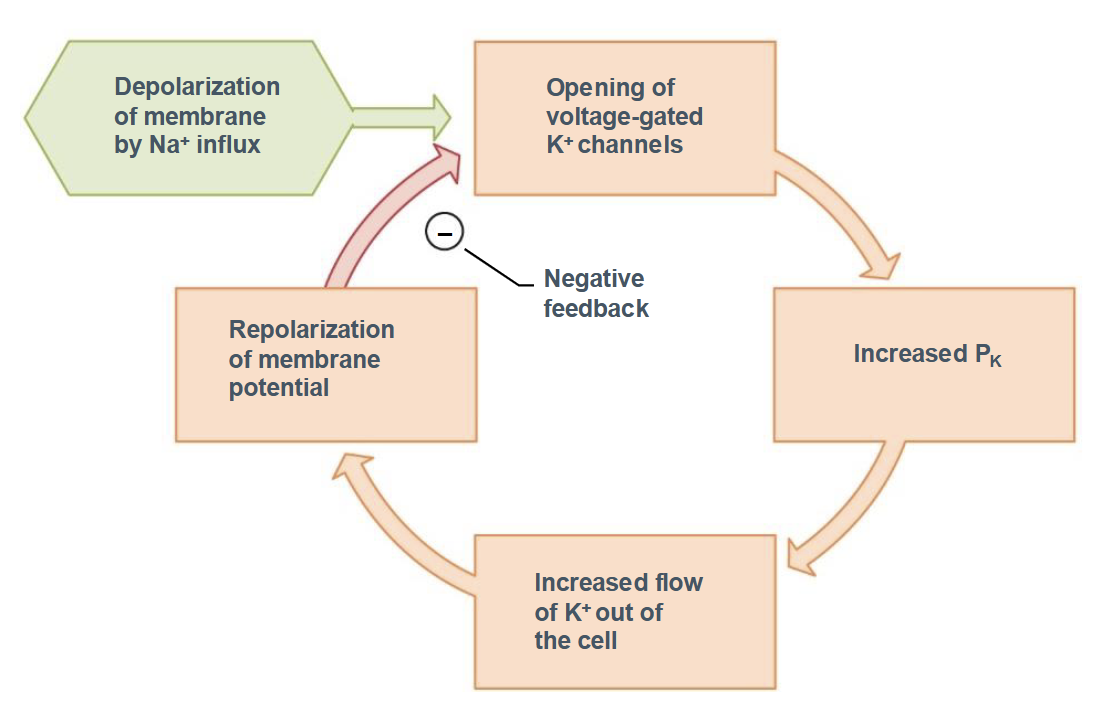

Function of Potassium Ion Channels

Depolarization of the membrane by Na+ influx

Opening of voltage-gated K+ channels

Increased PK

Increased flow of K+ out of the cell

Repolarization of the membrane potential leads to negative feedback loop

Refractory Period

The short time after a cell (usually a neuron or muscle cell) fires an action potential during which it cannot fire again normally. It can be:

Absolute

Relative

Absolute refractory period

No second action potential is possible, no matter how strong the stimulus.

Happens because voltage-gated Na⁺ channels are inactivated.

This guarantees that action potentials move in one direction only down the membrane

Relative refractory period

A second action potential is possible, but only with a stronger-than-normal stimulus

Occurs while K⁺ channels are still open and the membrane is hyperpolarized

Some Na+ channels have reset, but some are still inactivated

Action potential propagation

the movement of the action potential along the membrane of an axon or muscle cell

The signal does not weaken as it travels (it’s all-or-none), because the action potential is regenerated at each segment of membrane

Saltatory conduction

Myelin insulates the axon

Action potentials occur only at Nodes of Ranvier

Signal “jumps” node to node

Much faster and more energy efficient

Nodes of Ranvier

small, unmyelinated gaps between adjacent myelin sheath segments along a myelinated axon

Rich in voltage-gated Na⁺ (and K⁺) channels

Site where action potentials are regenerated

Enable saltatory conduction (the signal “jumps” from node to node)

Why might there be two different kinds of chemical synapses?

excitatory

inhibitory

the nervous system needs both acceleration and braking to function properly

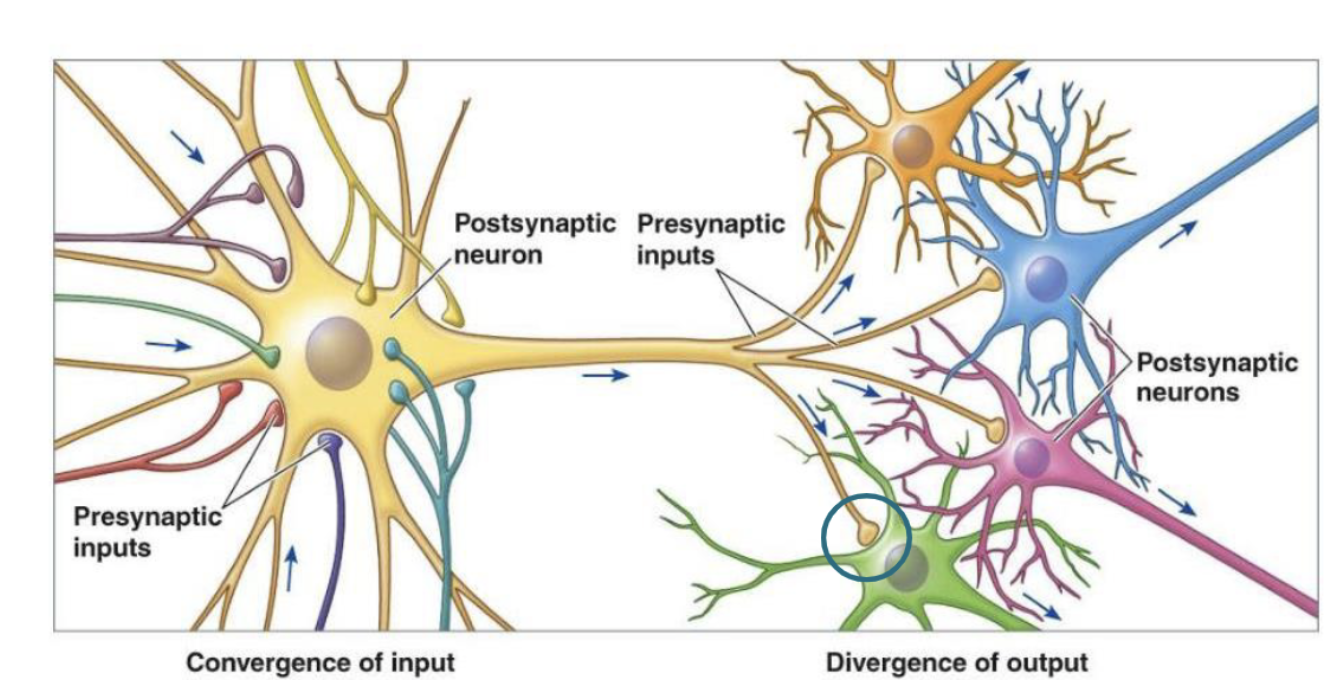

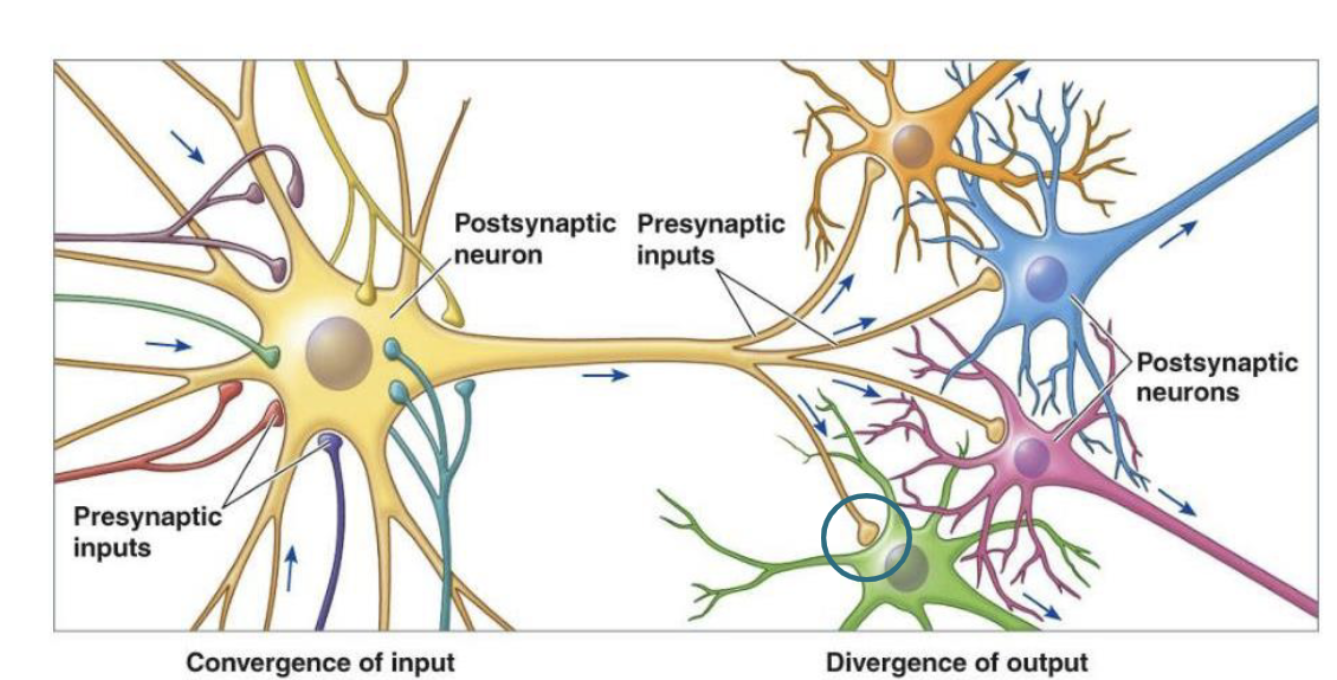

Convergence of input

one cell is influenced by many others

Divergence of input

one cell influences many others

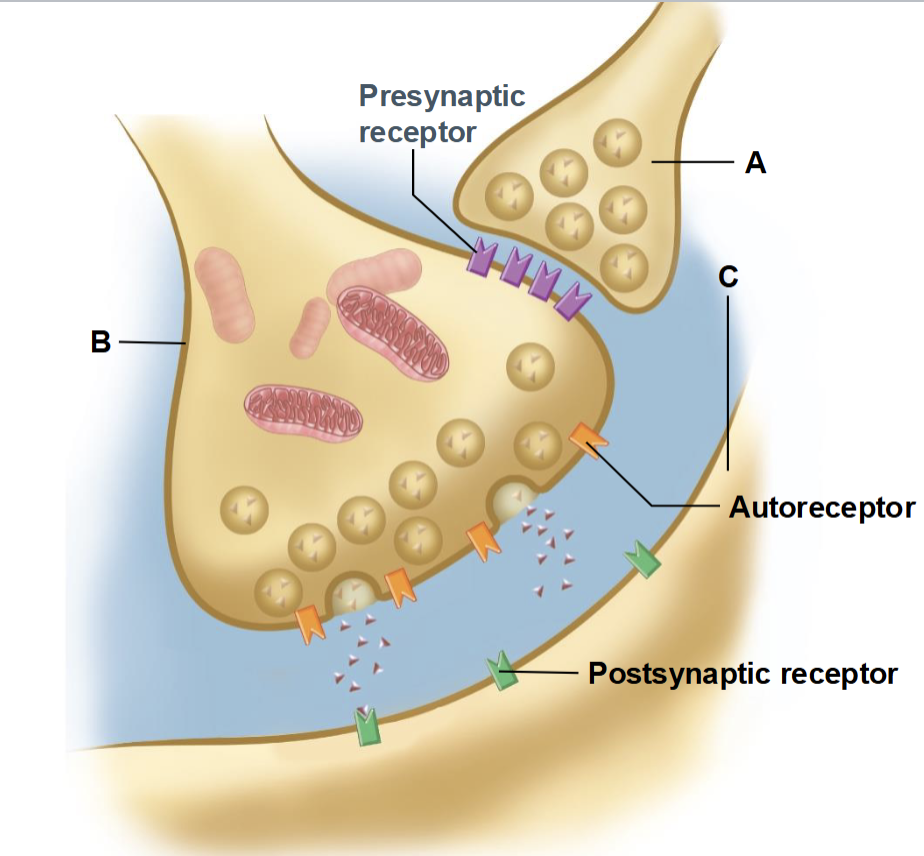

Steps of Activating a Presynaptic Cell

Action potential reaches axon terminal

Voltage-gated Ca2+ channels open

Calcium enters the axon terminal

Neurotransmitters are released and diffuse into the synaptic cleft

Neurotransmitters bind to their postsynaptic receptors

Neurotransmitters are removed from the synaptic cleft

Vesicle docking

the step in synaptic transmission where neurotransmitter-filled synaptic vesicles attach to the presynaptic membrane, positioning them for release

Occurs at the active zone of the presynaptic terminal

Mediated by SNARE proteins

Puts vesicles in a ready-to-release state

After docking, an incoming action potential opens voltage-gated Ca²⁺ channels → Ca²⁺ enters → triggers vesicle fusion and exocytosis of neurotransmitter.

Synaptotagmin Function

the calcium sensor that triggers neurotransmitter release at chemical synapses

An action potential reaches the presynaptic terminal

Voltage-gated Ca²⁺ channels open → Ca²⁺ enters

Ca²⁺ binds to synaptotagmin on the synaptic vesicle

Synaptotagmin changes shape and interacts with SNARE proteins

This causes vesicle fusion with the presynaptic membrane and exocytosis of neurotransmitter

SNARE Proteins Function

Mediate synaptic vesicle docking and fusion by forming a complex that pulls the vesicle and presynaptic membranes together, enabling neurotransmitter release

These proteins zip together, pulling the vesicle tightly against the membrane

Provide the mechanical force needed for membrane fusion

Ensure vesicles fuse at the correct location (active zone)

Allow rapid, Ca²⁺-triggered exocytosis once synaptotagmin is activated

Partial fusion

The vesicle briefly contacts the presynaptic membrane

A small fusion pore opens

Some neurotransmitter is released

Vesicle then detaches and is recycled

Fast and energy-efficient, allows rapid, repeated signaling

Complete fusion

The vesicle fully merges with the presynaptic membrane

All neurotransmitter is released

Vesicle membrane becomes part of the presynaptic membrane

Requires endocytosis to retrieve membrane

ensures maximal transmitter release when needed

Ionotropic receptors

Ligand-gated ion channels that open directly upon neurotransmitter binding, allowing rapid ion flow and fast synaptic signaling

Neurotransmitter binding causes an immediate conformational change

Ions (Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺, or Cl⁻) flow across the membrane

Produce fast, short-lasting postsynaptic responses

Generate EPSPs (depolarization) or IPSPs (hyperpolarization)

Examples: Nicotinic ACh receptors (neuromuscular junction), GABA

Metabotropic receptors

G-protein–coupled receptors that indirectly modulate ion channels or intracellular signaling pathways, producing slower but longer-lasting effects on the postsynaptic cell

Neurotransmitter binding → receptor activates a G-protein

G-protein can:

Open/close ion channels indirectly

Activate second messenger pathways (cAMP, IP₃, DAG)

Effects are slower but longer-lasting than ionotropic responses

Often produce modulatory effects rather than direct depolarization or hyperpolarization

Examples: Muscarinic ACh receptors

Neurotransmitter Removal from Synapse

Enzymatic degradation → Ex. ACh broken down by acetylcholinesterase

Reuptake into presynaptic neuron → transporter proteins pump neurotransmitters back into the presynaptic terminal, they can be repackaged into vesicles or degraded by enzymes inside the neuron

Diffusion away from the synapse → then they can be taken up by nearby glial cells or diluted in ECF

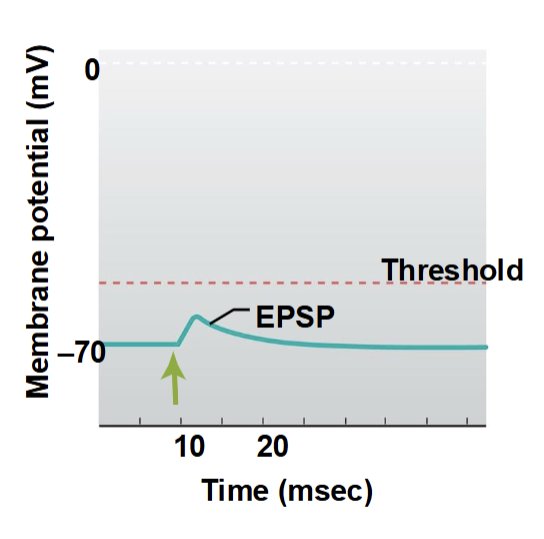

Excitatory Postsynaptic Potentials (EPSPs)

depolarizing postsynaptic potential caused by excitatory neurotransmitter binding, which increases the likelihood of an action potential

Caused by opening of ligand-gated ion channels (usually Na⁺ or Ca²⁺)

Results in positive charge entering the postsynaptic cell → membrane potential moves closer to threshold

Can summate (spatially or temporally) to trigger an action potential at the axon hillock

Example: ACh at nicotinic receptors

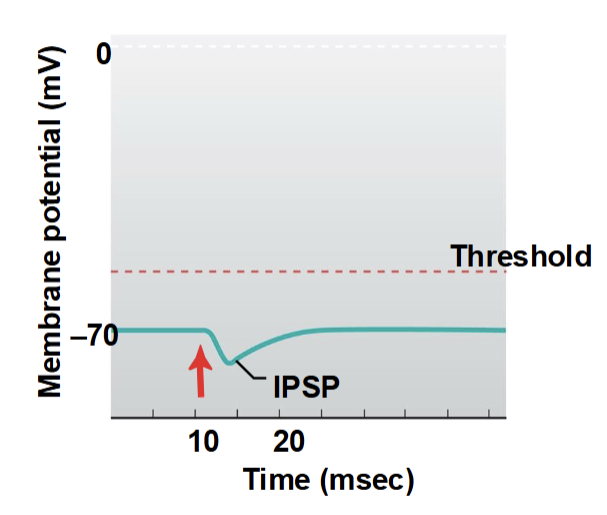

Inhibitory Postsynaptic Potentials (IPSPs)

a hyperpolarizing postsynaptic potential caused by inhibitory neurotransmitters, reducing the likelihood of an action potential

Typically caused by Cl⁻ influx or K⁺ efflux through ligand-gated channels

Temporal Summation

the additive effect of multiple postsynaptic potentials occurring in quick succession at a single synapse

Multiple EPSPs (or IPSPs) occur in rapid succession at the same synapse, and their effects add together

If the summed depolarization reaches threshold → action potential fires

Spatial Summation

the combined effect of postsynaptic potentials from multiple synapses occurring simultaneously on a neuron

The combined effect can bring the neuron to threshold or inhibit firing

Autoreceptors

presynaptic receptors that monitor and regulate the neuron’s own neurotransmitter release

Regulate neurotransmitter release, often providing negative feedback to prevent excessive release

Axo-axonic neurons

neurons that synapse onto the axon of another neuron to regulate its neurotransmitter release

Can modulate neurotransmitter release by either enhancing or inhibiting it (presynaptic inhibition or facilitation)