Recombinant DNA and cloning vectors

1/17

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

18 Terms

What is recombinant DNA technology?

It is the process of joining DNA molecules from different sources to form a new DNA sequence In vitro

It allows scientists to express, study, and manipulate genes in a chosen host. Applications include producing therapeutic proteins (e.g. insulin, interferons), studying gene function, and creating genetically modified organisms.

Define cloning vectors and give examples.

Cloning vectors are DNA molecules that carry foreign DNA into a host cell for replication or expression.

Hosts (cells) | bacteria, yeast, mammalian cells |

Vectors (DNA) | plasmids, bacteriophages, viral genomes, YACs |

Examples:

Plasmids – small circular DNA in bacteria.

Phages – bacterial viruses used for larger inserts.

Viruses – vectors for eukaryotic cells (e.g. lentivirus, baculovirus).

Artificial chromosomes – YACs (yeast artificial chromosomes) for very large DNA segments.

What makes plasmids useful as vectors?

They are discrete, circular double-stranded DNA found in many bacteria.

Key features:

Replicate independently of chromosomal DNA (extra-chromosomal).

Transferable between bacteria (e.g. antibiotic resistance).

Easily engineered to carry foreign genes and propagate them.

What key elements does a plasmid vector contain?

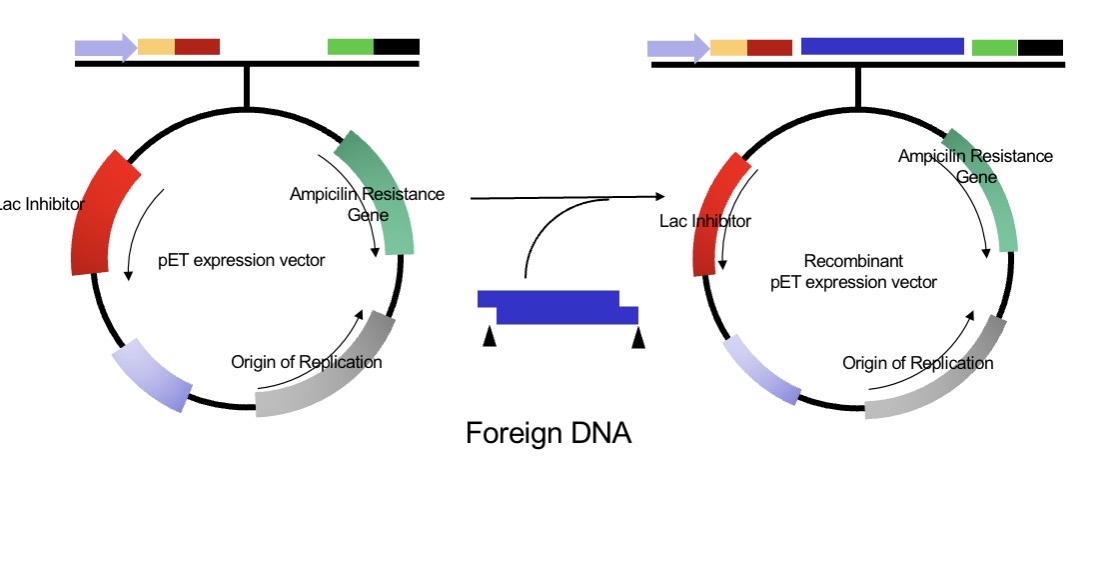

(Natural plasmid → engineered vector → + foreign DNA = recombinant plasmid.)

Origin of replication (ori): ensures replication inside host bacteria.

Selectable marker: e.g. ampicillin-resistance gene to identify cells with the vector.

Multiple cloning site (MCS): region with unique restriction enzyme sites for inserting foreign DNA.

Promoter/Regulatory elements: control gene expression.

Optional tags or reporter genes: aid protein purification or visualisation.

Why resistance genes are included in vectors

They act as selectable markers:

Bacteria are transformed with the plasmid

Cells are grown on antibiotic-containing media

Only bacteria that successfully took up the plasmid survive

This lets you easily identify transformed cells.

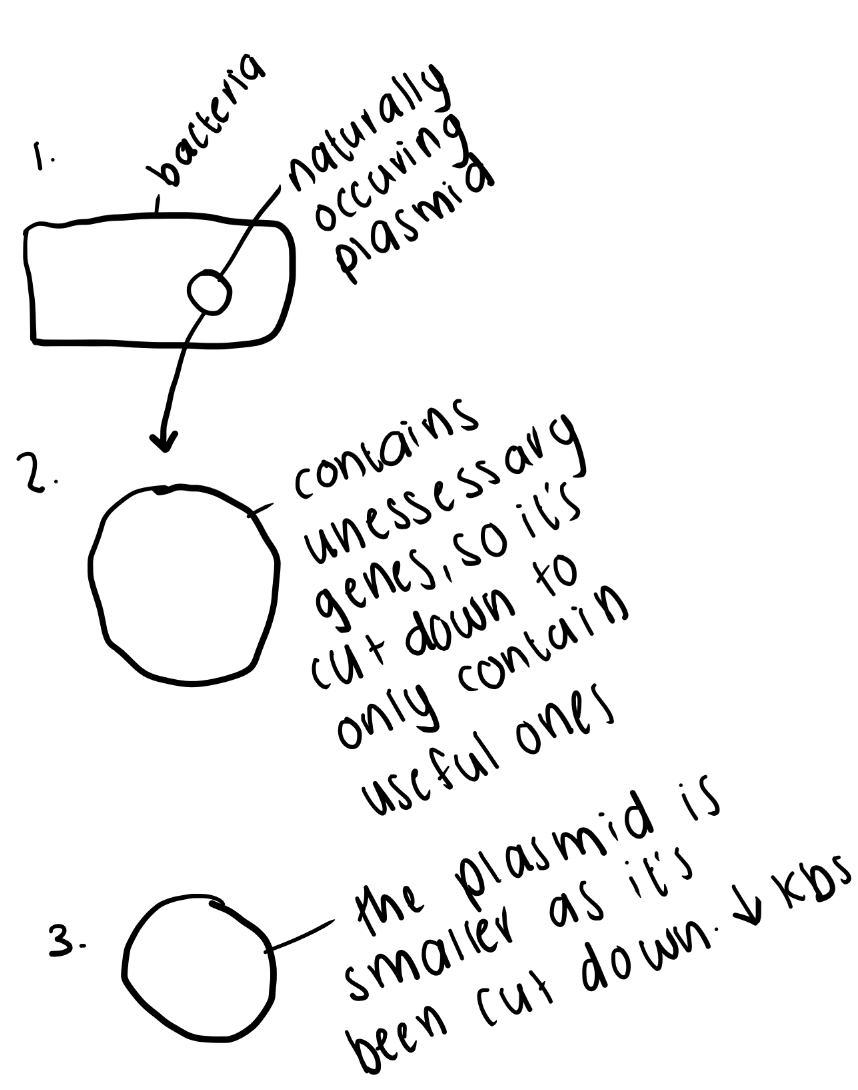

How are plasmid vectors modified for lab use?

Naturally occurring plasmids are “cut down” and engineered to be:

- Small (≈4–5 kb) and easy to manipulate.

- High copy number for high yield.

- Contain MCS and selectable markers.

- Able to accept DNA inserts without losing replication ability.

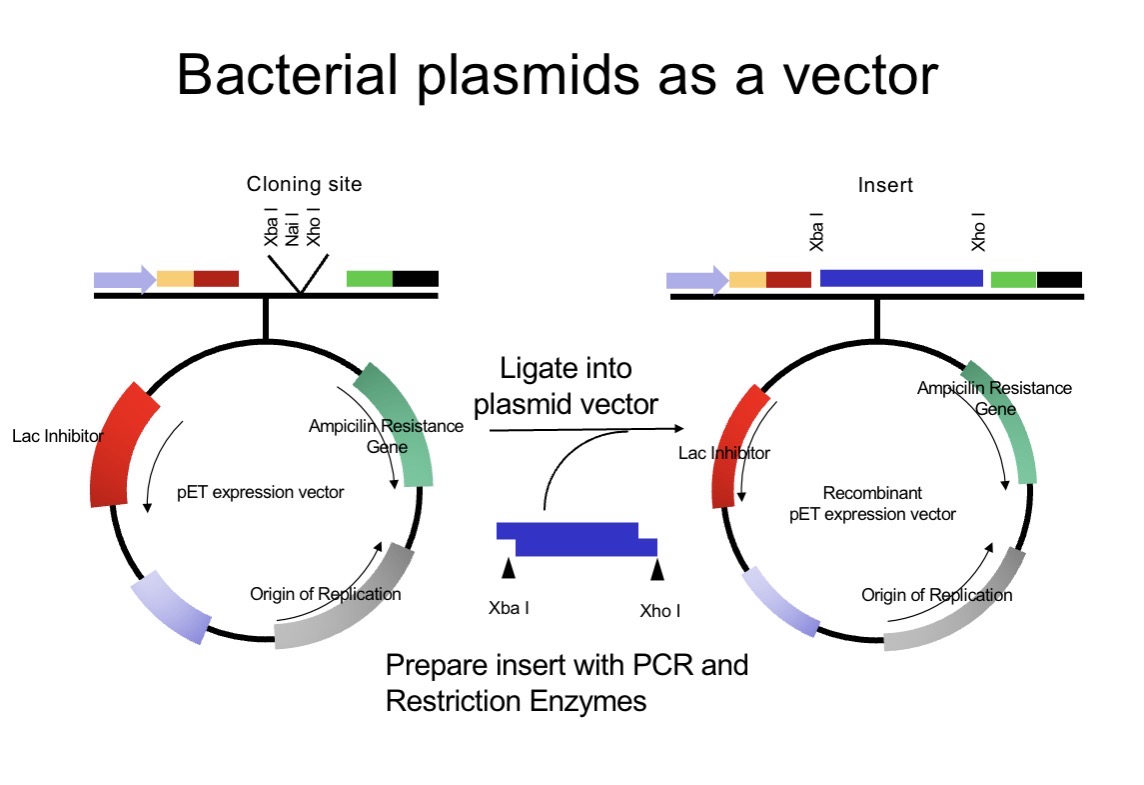

Steps in creating a recombinant plasmid

Cut the plasmid vector at specific restriction sites (e.g. XbaI, XhoI) at MCS

—> MCSs are deliberately placed in non-essential regions of the plasmid, so inserting DNA there does not disrupt functions the plasmid needs to survive and replicate.

—>Each site within the MCS is a restriction enzyme site, but the MCS itself is the collection of many such sites placed in a non-essential or controlled region of the vector to enable flexible, safe, and efficient cloning.

—>A plasmid usually contains a single Multiple Cloning Site and is cut once to allow insertion of one DNA fragment. This remains true whether one or two restriction enzymes are used, as two enzymes simply create different ends at the same insertion site to control orientation. As a result, each plasmid molecule normally receives only one insert.

Insert foreign DNA fragment.

Ligate insert to the vector with DNA ligase.

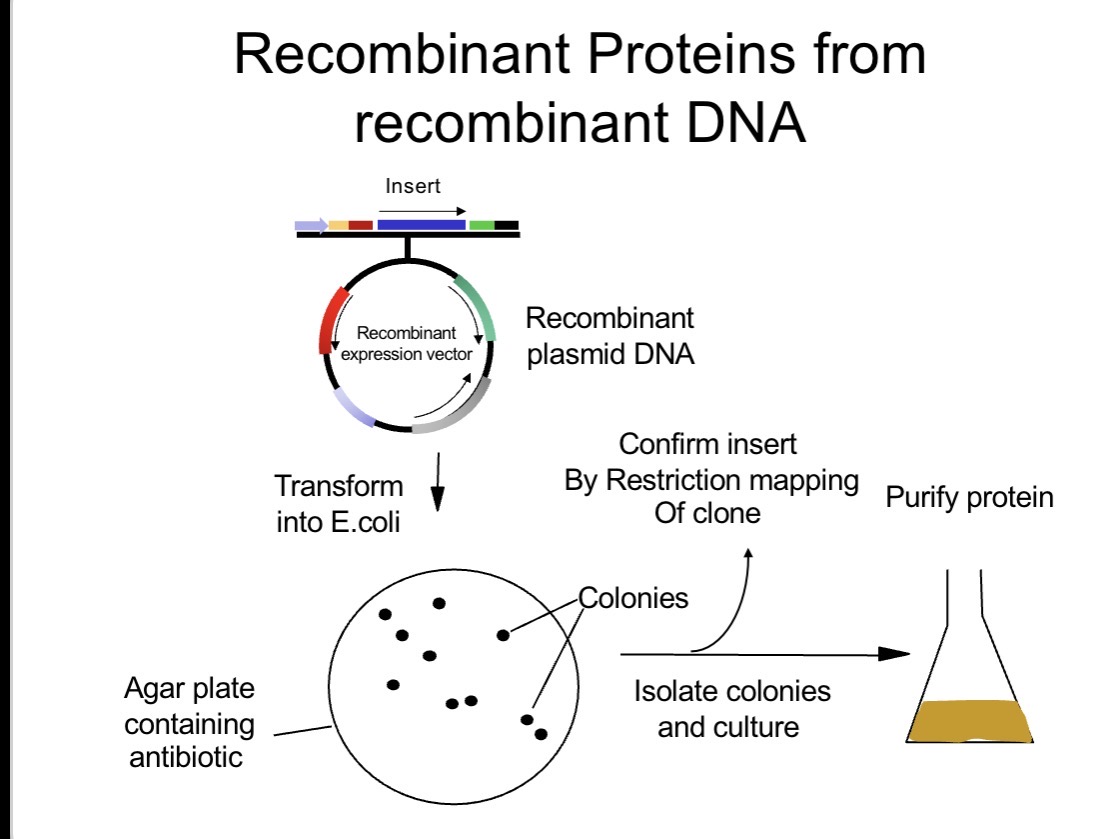

Transform into E. coli.

Select colonies on antibiotic agar.

Confirm insert by restriction mapping or sequencing.

A bacterial plasmid vector is an engineered circular DNA that contains an origin of replication (so it can copy inside bacteria), an antibiotic resistance gene (so you can select cells that took it up), and a multiple cloning site (MCS) with several restriction enzyme sites where you insert foreign DNA. First, you PCR-amplify your gene of interest and design the primers so the PCR product gains restriction sites (e.g., XbaI on one end and XhoI on the other). You then cut both the plasmid vector and the PCR insert with the same restriction enzymes so they produce matching sticky ends, allowing the insert to base-pair into the opened plasmid in a controlled orientation (directional cloning). DNA ligase then seals the sugar-phosphate backbone by forming phosphodiester bonds between 3’-OH and 5’-phosphate ends, creating a recombinant plasmid. Finally, you transform the recombinant plasmid into bacteria, plate on the relevant antibiotic (e.g., ampicillin) so only plasmid-containing colonies grow, and verify the correct insert by digest/PCR and ideally sequencing

Why use plasmids as recombinant tools?

They enable controlled gene expression in living organisms for research and biopharmaceutical production.

Plasmids are used as recombinant tools because they allow foreign genes to be inserted into living cells and expressed in a controlled way. They contain engineered elements such as promoters, selectable markers, and fusion tags that enable regulation of gene expression, easy identification of transformed cells, and purification or tracking of the expressed protein. This makes plasmids essential for research applications and for producing biopharmaceutical proteins.

Benefits:

- Can alter protein properties or localisation.

- Allow inducible or high-level expression.

- Support fusion to tags for purification or therapeutic use.

Examples of recombinant proteins in medicine

Human insulin → diabetes.

Interferons α & β → viral hepatitis, MS.

Erythropoietin → anaemia from kidney disease.

Factor XIII → haemophilia.

TPA → stroke and embolism.

Humanised antibodies → biologics (>50 % of new drug approvals in recent years).

What are the requirements for a bacterial expression plasmid?

For vector:

Origin of replication functional in E. coli.

Antibiotic marker (e.g. ampicillin).

Multiple cloning site with restriction sites (EcoRI, BamHI, HindIII, XhoI, XbaI).

For insert(gene + these factors provided by vector):

Bacterial promoter (con- or inducible)

Shine-Delgarno sequence is the ribosomal binding site found 8 nucleotides before the start codon AUG

Terminator sequence(RNA pol unbinds )

lacI gene (lac repressor) if using an inducible lac system

In its native genome, a gene usually includes a promoter, Shine–Dalgarno sequence, start codon, coding region, and terminator, but when genes are cloned into plasmids, only the coding sequence is typically inserted. The necessary regulatory elements for transcription and translation are instead provided by the expression vector to ensure controlled, efficient expression in the host organism.

In bacteria, a gene coding sequence alone is insufficient for expression. Efficient expression requires a bacterial promoter to initiate transcription, a Shine–Dalgarno sequence to recruit and align the ribosome for translation at the AUG start codon, and a transcriptional terminator to ensure proper termination and mRNA stability. Only when all these control elements are present can reliable gene expression occur.

Difference between constitutive and inducible promoters?

Constitutive: always on → continuous protein production.

Bad if protein is toxic

Inducible: off until triggered (e.g. by lactose or IPTG). Useful when protein is toxic or burdensome to cells.

—> An inducible promoter is a promoter that is normally OFF and only turns ON when a specific signal (inducer) is added. This gives you control over when a gene is expressed.

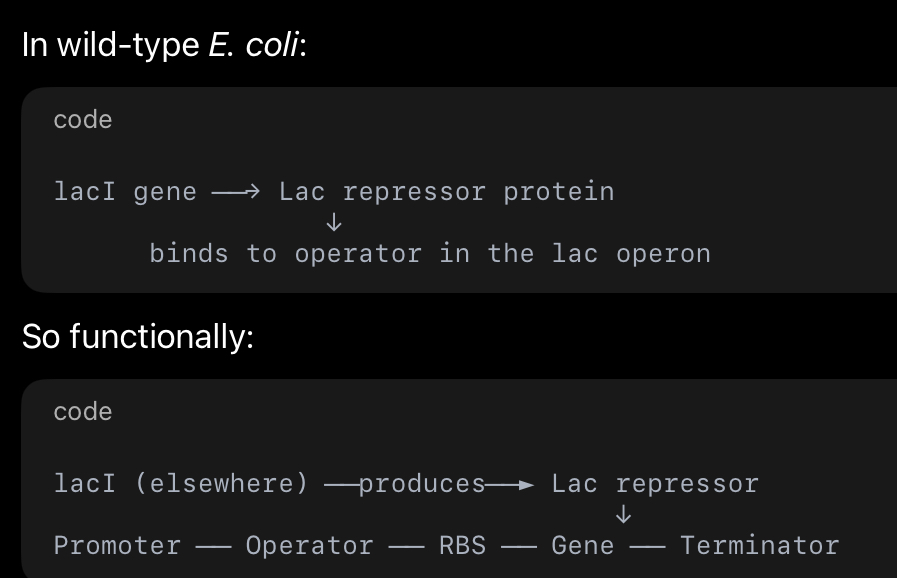

How does the lac inducible system work?

Promoter ── Operator ── RBS (Shine-Dalgarno) ── AUG ── Gene ── Terminator

In an expression system, the plasmid vector already contains the regulatory DNA elements required for gene expression, including a promoter, operator, ribosome binding site, and terminator. When a foreign gene is inserted into the multiple cloning site, it becomes part of this operon-like expression cassette, allowing the host bacterial RNA polymerase to transcribe it under controlled conditions once the plasmid is inside the cell.

The lac operon process (step by step)

1) “OFF” state (no lactose / no inducer)

The cell has LacI repressor protein (made from lacI gene elsewhere).

Repressor binds the operator DNA sequence.

With the repressor sitting there, RNA polymerase can’t properly transcribe the downstream gene(s) (it’s blocked or can’t proceed).

Result: little to no mRNA is made → little to no protein from that gene.

2) “ON” state (lactose present / IPTG added)

Lactose enters the cell (or IPTG is added in lab).

Lactose is converted to allolactose (the true natural inducer) which binds LacI repressor

LacI repressor changes shape and releases the operator.

Now RNA polymerase binds the promoter and transcribes through the gene → mRNA is produced.

The mRNA contains the RBS (Shine–Dalgarno) and then AUG, so the ribosome binds and translation starts.

Translation continues until a stop codon.

Transcription stops when RNA polymerase hits the terminator DNA sequence.

Result: protein is made (your cloned gene is expressed).

3) When inducer is removed

Repressor can bind operator again → system goes OFF again.

In bacteria, mRNA does NOT “go to” the ribosome.Ribosomes bind to the mRNA while it is still being made.

Everything downstream of the promoter — including the SD sequence — is copied into RNA.

Requirements for DNA insert in bacterial expression

You take the gene required usually from a eukaryote (e.g. human), expressed in a prokaryote (E. coli).

Must contain start (AUG) and stop codons.

The gene taken must be cDNA only (no introns – bacteria cannot splice mRNA).

—>(Mature mRNA to cDNA via reverse transcriptase)

—> So the mRNA had all 3 modifications but the cDNA doesn’t keep the tail or cap when it’s being copied via reverse transcriptase

—>No poly-A signal or cap needed as bacteria don’t recognise or require them

Restriction sites can be added by PCR via primers

Should be in-frame with any tag or fusion sequence.

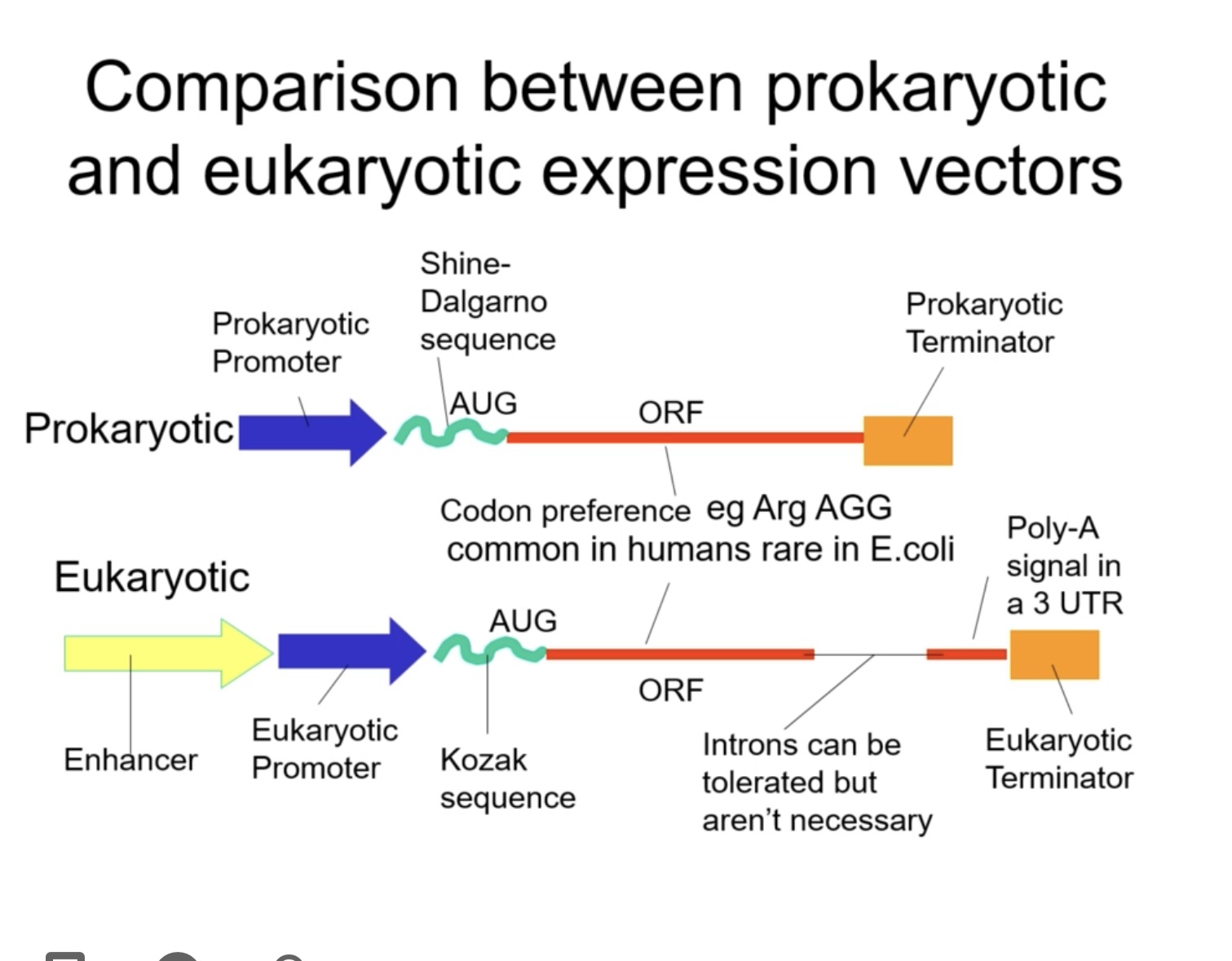

Why can’t a bacterial plasmid work in human cells?

Bacterial promoters and Shine–Dalgarno sequences aren’t recognised by eukaryotic RNA polymerase.

No 5′ cap or poly-A tail for mRNA stability.

Bacterial terminators and origins don’t function in eukaryotes.

Key elements of a eukaryotic expression vector

(Some proteins(created by insert) are best made in a eukaryotic cell instead of a prokaryotic vector like a plasmid.)

Eukaryotic vector:

Eukaryotic promoter (e.g. CMV, RSV, SV40).

Kozak sequence (helps ribosome recognise start codon).

Poly-A signal (3′ UTR for mRNA stability).

—> DNA: ──AATAAA───────────────→→→

—>RNA: ──AAUAAA────────extra RNA────────

Eukaryotic terminator

Selectable marker (e.g. G418 resistance).

Sometimes dual bacterial/eukaryotic elements for growth in E. coli and expression in mammalian cells.

For what’s being inserted into the cell It can be:

Transient: recombinant eukaryotic plasmid remains episomal (non-integrated); short-term expression.

Stable: plasmid integrates into host chromosome; long-term expression; requires selection (e.g. G418).

Transient vs stable expression is about what happens after the recombinant eukaryotic expression vector is taken up by a eukaryotic cell.

(Plasmids are circular, extrachromosomal DNA molecules found naturally in bacteria and some lower eukaryotes (e.g. yeast), but not naturally in humans, although plasmids can be introduced into human cells experimentally as expression vectors.)

The gene inserted into a eukaryotic expression vector can come from either:

• a eukaryote (e.g. human gene), or a prokaryote (e.g. bacterial gene)

What matters is where you want to express the gene, not where it originally came from.

If the gene comes from a prokaryote, it has no introns anyway, usually works fine

If the gene comes from a eukaryote, it is often inserted as cDNA (no introns), ensures proper expression

Most gene inserts are from eukaryotes

Purification

Make recombinant vector in bacteria( In recombinant DNA technology, bacteria are first used to amplify the recombinant plasmid, after which the plasmid DNA is purified before being introduced into the final host cell for expression. Bacteria are often used TWICE for different reasons -Once to make lots of DNA, and once to make protein(expression)

Purify the recombinant DNA (plasmid)

Introduce purified plasmid into host cell (bacteria or eukaryote)

Gene is expressed via transcription and translation → protein made

Protein is purified (NOT the DNA)

So:

DNA purification happens before expression

Protein purification happens after expression

Purification of the recombinant vector in bacteria:

Step 1: Grow bacteria

Bacteria contain the recombinant plasmid.

Grow them in liquid media → many cells.

Step 2: First centrifugation (collect cells)

Spin the culture.

Whole bacterial cells pellet at the bottom.

Liquid media stays on top → throw it away.

Why centrifuge here? To collect the cells, not the DNA.

Step 3: Lyse the cells

Add chemicals to the cell pellet.

Cells break open.

DNA and everything else is released.

Step 4: Second centrifugation (separate DNA types)

Spin the lysed mixture.

Pellet: cell debris, chromosomal DNA(long and tangled), denatured proteins

Small circular plasmid DNA stays in the liquid (supernatant)

This is the important centrifuge for DNA.

You keep the supernatant because it contains plasmid DNA.

Step 5: Final clean-up

Use a column or precipitation.

Remove salts and RNA.

End with pure plasmid DNA.

Purification of protein from recombinant DNA:

Step 1-3 are these same

Second centrifugation (remove debris)

Spin the lysed mixture.

Debris and membranes pellet.

Proteins stay dissolved in the supernatant.

This centrifuge is NOT selecting a specific protein.

It only removes junk.

Step 3: Purify the protein

Use a column (often via a tag).

Protein binds → others wash away.

Elute → pure protein.

By adding a fusion tag to the protein:

- 6×His-tag: binds nickel columns for affinity purification.

- GST-tag: binds glutathione columns.

These tags simplify purification and can be removed by proteases if needed.

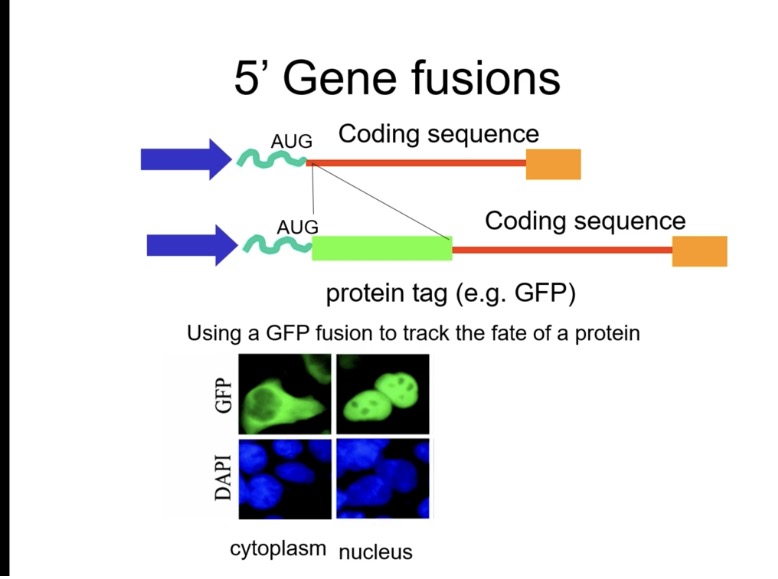

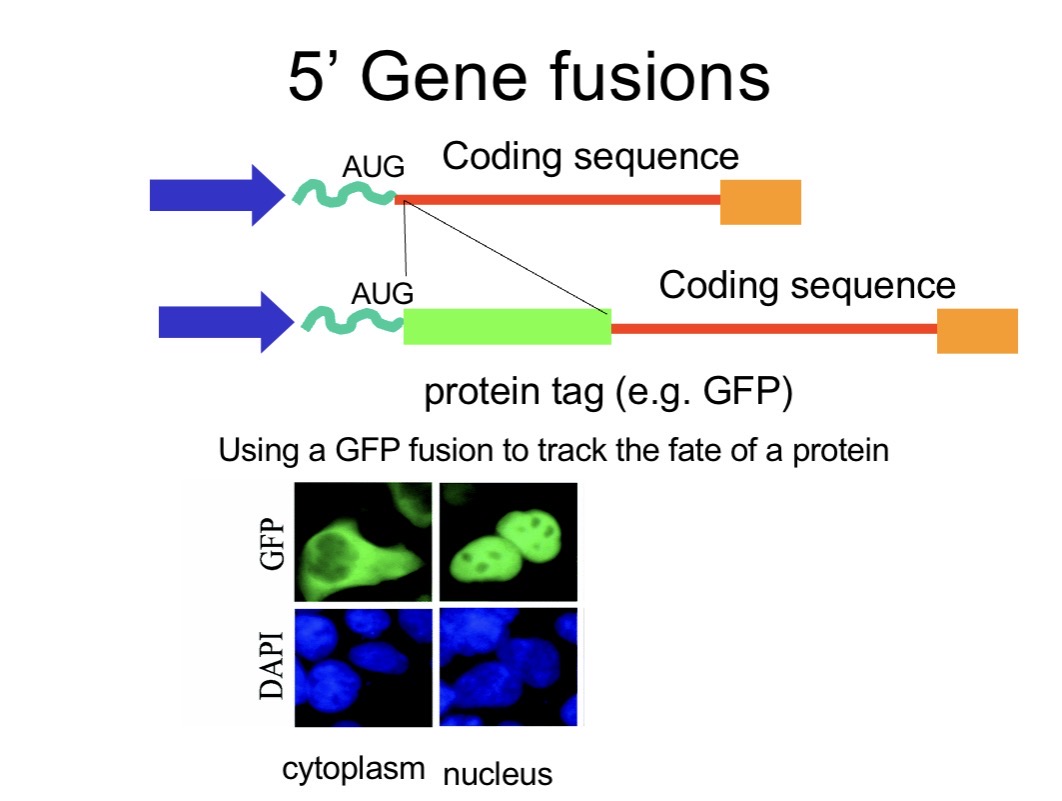

How can you study where a protein goes inside a cell?

Main question: Where did the protein go in the cell? Is it in the nucleus, or on the cell membrane??

GFP is added when you build the recombinant vector, in vitro:

You design the plasmid so that:

GFP is already in the vector, or

your gene is fused to GFP (gene–GFP fusion)

Fuse the gene to a reporter like GFP (green fluorescent protein).

When expressed, the fusion protein emits green fluorescence, allowing visualisation under a fluorescence microscope → detect nuclear, cytoplasmic or membrane localisation.

Why use fusion proteins or tags?

Aid purification and detection.

Track localisation (GFP).

Improve solubility and stability (GST).

Allow pull-down experiments to study protein interactions.

List common uses of different vectors in genomics.

Plasmids → gene expression in bacteria.

Viral vectors → gene delivery into mammalian cells.

YACs → cloning large DNA segments for genomic studies.

Dual vectors → expression in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes.

Additional Clarifications

Kozak sequence: consensus around start codon (5′-GCC(A/G)CCAUGG-3′) that helps eukaryotic ribosomes initiate translation efficiently.

Poly-A signal: e.g. AAUAAA; ensures polyadenylation and mRNA stability.

Shine–Dalgarno sequence: prokaryotic ribosome-binding site upstream of AUG.

IPTG: a non-metabolisable lactose analog that induces lac-based promoters without being broken down by cells.

Dual vectors: carry both bacterial and eukaryotic origins and markers so the same construct can be amplified in E. coli then transfected into mammalian cells.