Exam 4 Textbook Questions

1/36

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

37 Terms

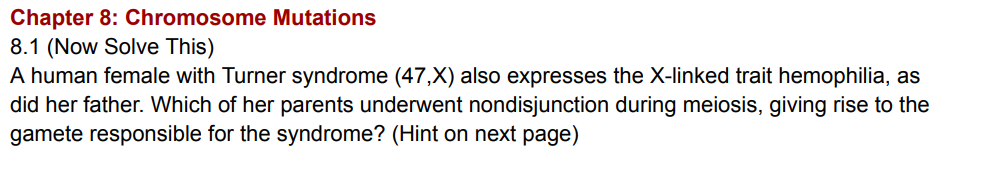

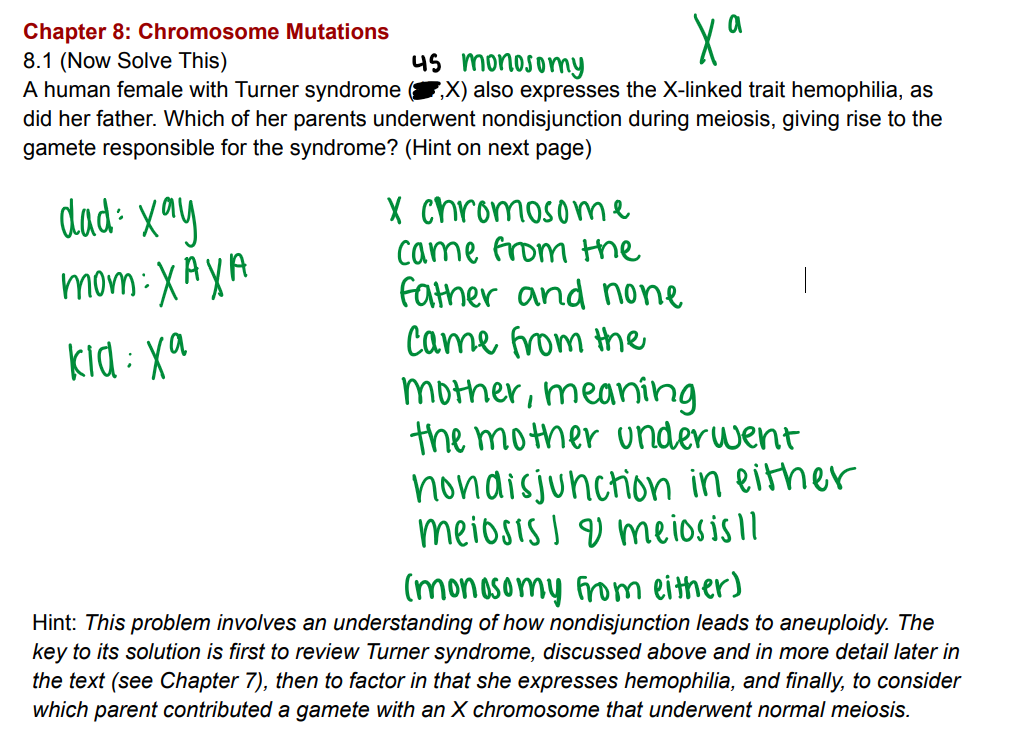

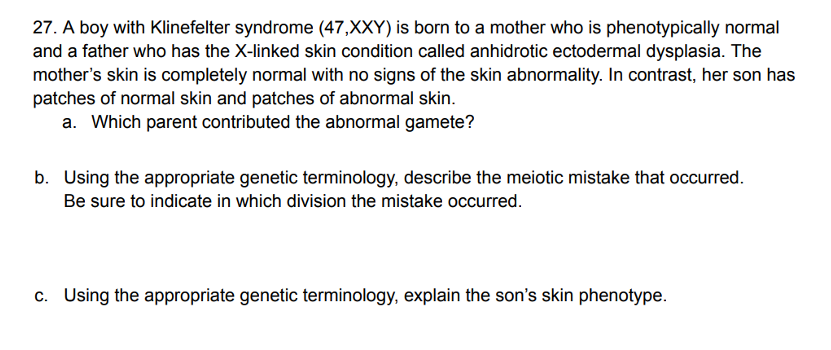

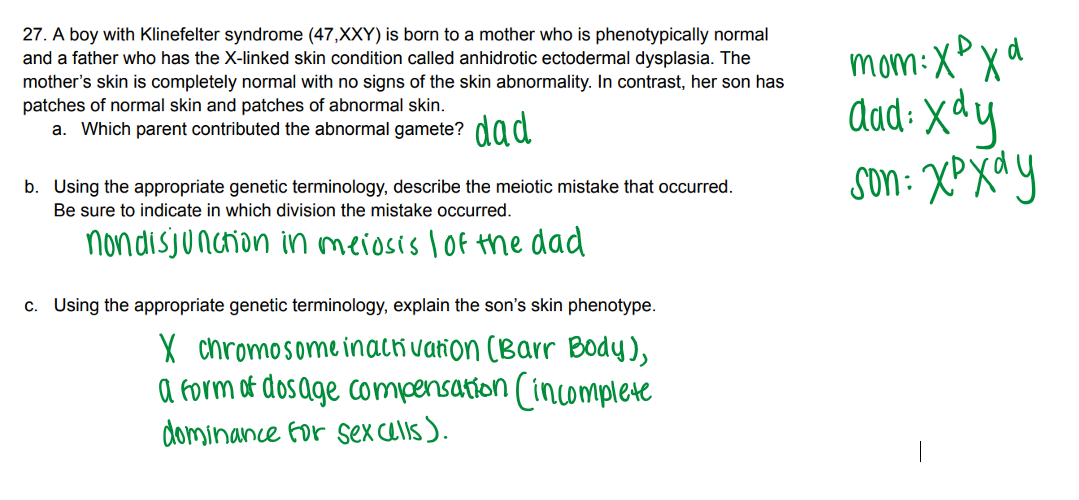

Mother underwent nondisjunction in either meiosis I or meiosis II

a) yes b) no

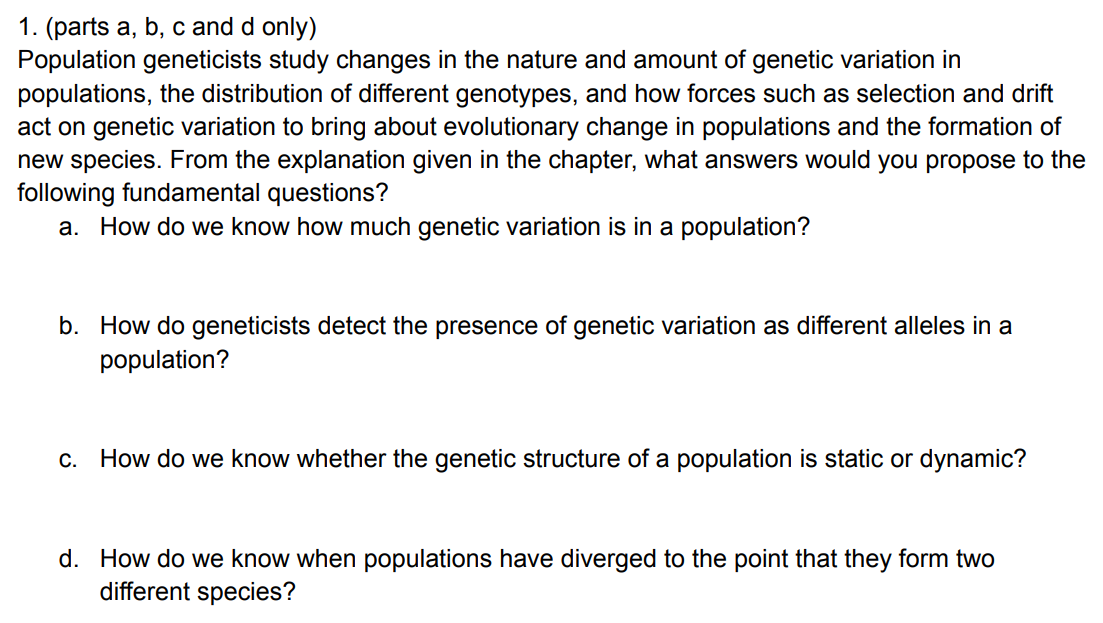

a. Genetic variation can be assessed in a variety of ways including responses to artificial selection and sequencing of nucleic acids and proteins.

b. Different alleles will show typical segregation patterns, and although they will have similar nucleotide and amino acid sequences, some differences will exist between them.

c. By conducting assays of allele and/or genotypic frequencies over time and space, one can determine whether the genetic structure of a population is changing.

d. If gene flow between populations becomes sufficiently reduced, divergence may have reached a point where the populations are reproductively isolated. Under this condition, they are usually considered different species.

What are considered significant factors in maintaining the surprisingly high levels of genetic variation in natural populations?

The presence of selectively neutral alleles and genetic adaptations to varied environments contribute significantly to genetic variance in natural populations.

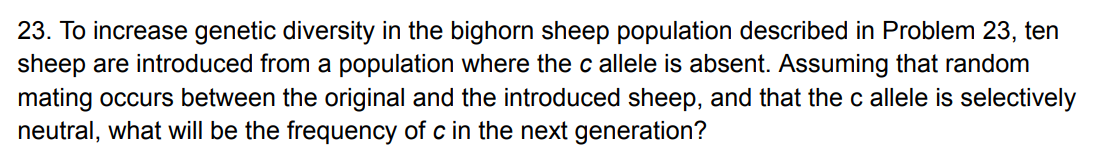

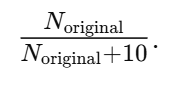

the next-generation frequency of c is the old frequency multiplied by the dilution factor

Population size matters because genetic drift is much stronger in small populations. When populations are small, random sampling can cause alleles to be lost or fixed by chance, regardless of whether they are beneficial or harmful. As a result, advantageous mutations can disappear simply because they are not passed on, and deleterious mutations can become fixed, sometimes leading to extinction.

A population bottleneck reduces population size, which increases genetic drift and inbreeding. Random fluctuations can raise the frequency of deleterious alleles by chance, and inbreeding increases homozygosity, making recessive disease alleles more likely to be expressed. Because many genetic diseases are recessive, bottlenecks lead to a higher frequency of genetic disease in the population.

A single guide RNA (sgRNA) is an engineered RNA molecule that combines the functions of crRNA and tracrRNA into one RNA. It contains a ~20-nucleotide sequence that is complementary to a target DNA sequence and a scaffold region that binds the Cas9 protein. In eukaryotic genome editing, the sgRNA guides Cas9 to a specific DNA site, where Cas9 creates a double-strand break, allowing the DNA to be edited during repair.

Dominant disease mutation (usually heterozygote): you want to disable/knock out the dominant mutant allele (often with an allele-specific sgRNA) so the remaining wild-type allele can provide normal function.

Recessive disease mutation (often homozygous): you need to replace or add a functional wild-type copy of the gene (because there isn’t a working allele to rely on).

Gene editing directly removes, corrects, or replaces a defective gene at its original location, sometimes changing only one or a few DNA bases or replacing the gene entirely.

In contrast, traditional gene therapy works by adding an extra therapeutic gene that coexists with the defective gene rather than fixing it. Gene editing differs because it allows precise correction and helps avoid a major problem of traditional gene therapy: random DNA integration.

Two common gene-silencing techniques are RNA interference (RNAi) and antisense RNA.

RNA interference (RNAi): Double-stranded RNA is introduced into cells and cleaved by Dicer into short siRNAs. These siRNAs form a complex that binds to complementary mRNA, causing its degradation or blocking its translation. In gene therapy, RNAi can be used to reduce or eliminate expression of harmful genes, such as disease-causing or overactive genes.

Antisense RNA: A strand of RNA complementary to a specific mRNA is introduced into the cell. By binding to the mRNA, it blocks translation into protein. In gene therapy, antisense RNA can be used to silence genes whose protein products cause disease.