Intro to Finance Midterm

1/90

Earn XP

Description and Tags

MGCR 341

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

91 Terms

cost benefit analysis

any decision where benefits exceed costs drive value for the firm

role of competitive markets

goods can be bought and sold at the same price, and the market price is what determines the value of the goods. when benefits exceed costs for a decision, the firm’s market value increases

the valuation principle

value of an asset to investors/the firm is determined by the market price

interest rate (r)

rate at which money can be borrowed or lent over a given period

higher interest rate: costs more to borrow money, cost of money is higher

interest rate factor (1+r)

rate of exchange between future $ and $ today

discount factor 1/(1+r)

the value of $ today received in the future

future value

the value of a cash flow that has moved forward in time

FVn = PV0 (1 + r)n

present value

the value today of a future cash flow

PV0 = Ct /(1+r)t

net present value

the difference between present value of benefits and costs

NPV = PV (benefits) - PV (costs)

impact on firm value: positive projects increase firms NPV

accept positive NPV projects, choose investments with highest NPV

role of financial markets and assumptions

allocate resources over time and allow people to obtain personal risk-return combination

assume that these financial markets are efficient and there is free access to them

preferences

don’t matter unless you don’t have free access to a given market since you can buy and sell to get what you like

law of one price

in competitive markets, assets and portfolios with the same cash flows must have the same price

arbitrage

Exploiting inefficiencies in the market, can borrow capital to exploit an opportunity.

An arbitrage opportunity is any situation in which it is possible to make a profit without taking any risk or making any investment

transaction costs

most markets have these, including commissions for brokers, bid (price when selling), and ask (price when buying): spread (difference between bid and ask)

compounding

the process of earning interest on previous interest, accumulating interest over time on an investment to earn more interest

simple interest

interest earned on just the initial principle

relationship between fv and pv

FVn = PV0 (1 + r)n

you’d be indifferent between the two since they are equal, what changes is when they’re received

combining and comparing cash flows

only values at the same period in time can be compared or combined

perpetuity

a stream of equal cash flows that occur regularly and last forever

first cash flow happens at t=1 (a year from the present)

PV0(perpetuity) = c/r

annuity

a stream of equal cash flows arriving at regular intervals over a specific period of time (not forever) where the first cash flow happens at t=1

PV0 (annuity) = (c/r)(1-(1/(1+r)^n)

FVn (annuity) = c/r (1+r^n -1)

OR

FVn (annuity) = PV0 (annuity) (1+r)^n

growing perpetuity

a stream of cash flows that occurs at regular intervals and grows at g forever

PV0 (growing perp.) = c/(r-g)

growing annuity

a stream of n growing cash flows paid out periodically and regularly

PV0 (growing annuity) = (c/(r-g) * (1- ((1+g)/(1+r))n

EAR

the total amount of interest that will be earned at the end of one year

adjusting the discount rate to different periods

cash can arrive at different time intervals. when computing PV or FV, you should adjust the discount rate to match the time period of cash flows.

equiv. n period effective rate = (1+r)n - 1

APR

Indicates the amount of simple interest earned in a year without considering the effects of compounding that may occur

an indirect way of quoting

can keep APR if the frequency of compounding is equal to the making of payments (otherwise have to convert)

APR to EAR conversions

per compounding period:

EAR = (1+ (APR/m)m) - 1

continuous compounding:

EAR = eAPR - 1

pure discount loans

the borrower receives money today and repays a single lump sum at maturity

interest only loans

the borrower gets money today and pays interest each period and repays the entire principle at some point in the future

amortized loans

the borrower pays the interest plus some fixed amount

balloon/bullet payment

amount that the borrower needs to pay to liquidate loan before maturity

real vs nominal interest rates and cash flows

real: accounts for inflation

real CF = nominal CF/ (1+ i)t

real interest rate

convert nominal rate r into real interest rate rr

1+rr = (1+r)/(1+I)

rr = (r-I)/(1+I)

rr = r - 1

where I is the expected annual inflation

when I = r, rr = 0

when i<r (i inflation is less than the rate r): real interest rate > 0 (positive)

when i>r (i inflation is greater than the rate r): real interest rate < 0 (negative)

be consistent with the discounting

the determinants of interest rates

The determinants of interest rates: fundamentally, interest rates are determined in the market based on governments, institutions, and individuals’ willingness to borrow and lend

some of the main factors:

inflation

expectations of future growth and productivity

central bank monetary policy

yield curve terms

key terms

term structure: the relationship between the investment term and the interest rate

yield curve: a plot of bond yields as a function of the bond’s maturity date

risk free interest rate: the interest rate at which money can be borrowed or lent without risk over a given period

PV of a stream of cash flows

cash flows should be discounted using the discount rate that is appropriate for their horizon

PV = sum of all { (ct/(1+rt)t)

where rt is the effective rate per period between 0 and t

overnight rate

the rate at which banks can borrow cash reserves on an overnight basis from the Bank of Canada

determines v short term interest rate

increasing yield curve

interest rates are expected to rise, long term rates higher than short term rates to attract investors

inverted yield curve (decreasing)

interest rates are expected to fall, long term rates are lower than short term rates to attract borrowers

connection to recessions: often inverted yield curves predict recessions

opportunity cost of capital

when calculating the NPV of an investment or project with risky cash flows, we need to use a discount rate that considers timing and the riskiness of the cash flows (because investors are usually risk averse)

cost of capital

the best available expected return offered in the market on an investment of comparable risk and term to the cash flow being discounted

bond

a security sold by a government or corporation to raise money from investors exchange for a promised future payment

debt

bond’s maturity

n, the final repayment date

coupon payments (CPN)

the promised interest rate of a bond paid periodically until maturity

CPN = (coupon rate * face value) / number of coupon payments per year

zero coupon bonds

payment structure that just pays face value at maturity

face value (fv)

the notional amount of the bond used to compute interest, usually repaid at maturity

yield to maturity (YTM)

the single discount rate that sets the pv of the promised bond payments = current market price of the bond

→ to discount, find the corresponding effective rate

coupon rate

sum of all coupons during a year divided by face value of the bond

determines the amount of each payment

price of a zero coupon bond

p = fv / ( 1 + YTMn)n

YTM of a zero coupon bond

YTMn = (fv/p)1/n - 1

YTM is expressed as an effective rate per period for holding the bond until maturity n periods in the future

return on bonds

return = (p1 - p0)/p0

(selling at t = 1)

buying at t=1 and getting fv at t=2

return = (fv1 - p1)/p1

coupon bonds

pays regular coupon interest payments (CPN) up to maturity (n) when it also pays its face value

return comes from: difference between purchase price and principal value and the periodic coupon payments

price of a coupon bond

p = (cpn/ytm) (1 - (1/(1+ytm)n)) + (fv/(1+ytm)n)

at par bonds

when price equals face value

at a premium bonds

price is greater than fv

at discount bonds

price is lower than fv

zero coupon bonds always trade at a discount

coupon bonds may trade at a discount (or at par or at premium)

bond prices just after a coupon

if the coupon rate = YTM: bond trades at par just after coupon payment

if coupon rate greater than YTM: bond trades at a premium just after coupon payment

if coupon rate less than YTM: bond trades at a discount just after coupon payment

time and bond price dynamics

if a bond’s YTM is known to remain constant, the per period return of an investment in the bond equals its YTM even if you sell the bond early

interest rate risk (risk factors in bond valuation)

the price of the bond changes due to changes in the interest rate → the bond price decreases when the interest rate rises. bond prices and interest rates move in opposite directions

credit risk (risk factors in bond valuation)

bonds typically have some probability of default → the risk that arises for bond owners from fluctuating interest rates.

all else equal, the prices of bonds with longer maturities are more sensitive to interest rate changes.

all else equal, the prices of bonds with higher coupon rates are less sensitive to changes in interest rates

the risk of default by the issuer of the bond, so that the bond’s cash flows are not known with certainty → to compensate, investors would either demand higher promised coupon payments or only will pay a lower price for the bond

if the bond has already been issued and the coupon rate is fixed, then higher default risk implies lower bond price, all else equal → at a fixed point in time, if the bond price decreases, YTM increases

firms rate the creditworthiness of bonds which are used by investors to make decisions (eg standard and poor’s, moody’s)

credit risk and yields for bonds

the YTM of a bond is calculated using the promised cash flows rather than expected cash flows

the YTM of a bond that has default risk ≠ the expected rate of return of investing in the bond

higher YTM ≠ an expected higher return for the bond

common stocks

partial ownership in a corporation

voting rights

dividends (decided by BOD) → proportional to ownership

public equity

traded on an exchange

private equity

not publicly traded

residual claim

common shareholders have claim over a firms cash flows and assets after all obligations to creditors and preferred shareholders are met

pre-emptive right

shareholders can share proportionally in new stock sold

limited liability

shareholders can only lose up to what they invested in the equity

payout policy

share repurchases: firms can use cash to buy back its own equity

cash dividends: payments made from firm’s earnings paid to shareholders

everything is at the board of directors’ discretion, and unless a dividend is declared by the board of directors, it isn’t a liability of the company

dividends and share repurchases are not tax deductible

can have regular and one time “special” dividends

preferred stock

usually no voting rights

preference in payments of div and liquidation (often fixed div rate)

common stock valuation

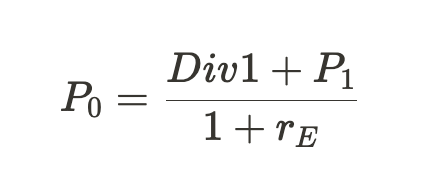

at t = 1: P0 = Div1 + P1

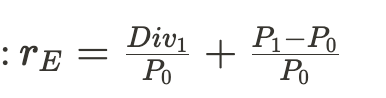

stock prices

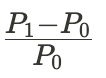

stock returns

dividend yield from re formula

capital gains yield from re formula

EQUITY VALUATION MODELS

dividend discount model

constant div growth model

constant growth model

total payout model

discounted FCF model

valuation by multiples

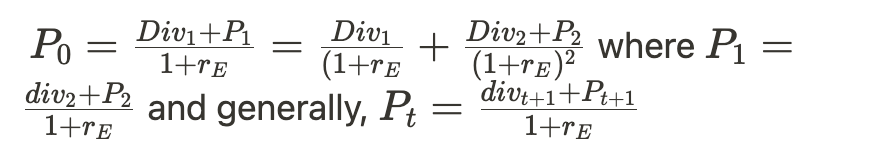

dividend discount model

generally: P0 = ∑divt / (1+rE)t

the price of a stock today = the pv of all future dividends

constant div growth model

P0 = Div1/(rE - g)

rE = Div1/P0 + g

where div yield: div1/p0

capital gains yield: g

constant growth model

P0 = divN/(1+rE)N + 1/(1+rE)N * divN+1/(rE -g)

dividends and growth, determining rate of growth for firms divs

divt = EPSt * Dividend Payoutt

where earnings are total profit minus depreciation, taxes and interest

EPS_t (earnings per share) = earnings/number of shares at time = t

dividend payout ratio_t: fraction of the earnings firms pay out as dividends in period t

if a firm has constant dividend payout ratio, the growth in dividends per share div_t is determined by growth in EPS_t

if all increases in future earnings are from new investments from RE

growth EPS rate = retention rate * return on new investment

where retention rate is fraction of earnings that the firm retains (that it doesnt pay out in dividends)

hence, the growth in EPS_t is determined by the retention rate and return on new investments

the total payout model

extends the div discount model to share repurchases

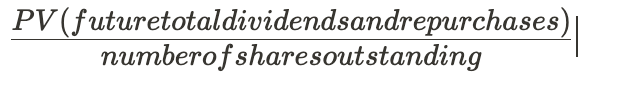

P0 =

where the numerator is the current value of firm’s equity which when you divide by denominator of # of shares gives price per share, P_0

discounted FCF model

DCF (discounted free cash flow model): enterprise value = market value of equity + debt - cash

where cash is excess cash beyond what is needed for operations

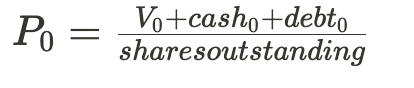

estimating stock price ind PV of firms FCF to pay all investors, enterprise value is V_0,

V_0 = PV (future free cash flow of firm)

free cash flow of a firm

how much cash is available to debt and equity holders after accounting for operating expenses, taxes, changes in working capital, and needed investments in fixed assets → ignores effect of firm debt

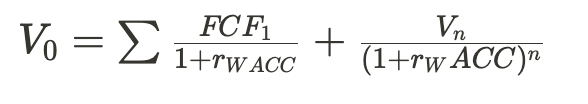

estimating a firms EV

since we discount the cash flows to all investors, we use the WACC (weighted average of cost of capital), denoted by r_{WACC}

Forecast FCF to some horizon (time n) together with the terminal value (beyond forecast period value of asset) of enterprise at time n

methods to estimate terminal value

liquidation value: firm stops operating at a foreseeable point in the future and will sell the assets, then the terminal value is the market value of those assets

multiple valuation: terminal value of the firm found by adding a multiple to expected earnings or revenues in that year (relative valuation)

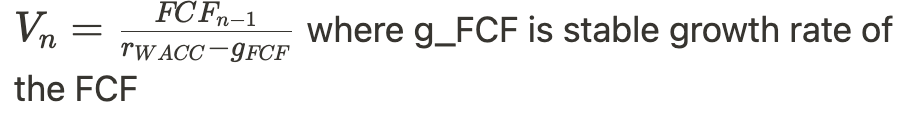

stable growth model: assumes that the cash flows beyond terminal year n will grow constantly forever. in this case, the terminal value is a growing perpetuity:

why does discounting a firm’s FCF give us the enterprise value (enterprise value = debt + equity - excess cash)?: because all of the firm’s FCF plus excess cash go to debt holders or shareholders

valuation by multiples

an asset should sell for $20 if it has 2x the cash flow as a very similar asset that sold for $10 recently

choose the right multiples and truly comparable firms

choosing the right firms to compare with

similar enough to be comparable, need a large sample to filter out unique features

eliminate firms with rare events

criteria:

industry classification

technology

clientele

size

leverage (equity with different financial risk)

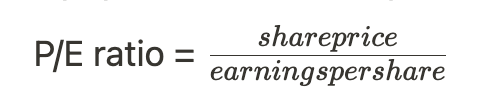

valuation by multiples: P/E ratio

trailing p/e

to estimate the value of a firms share price, multiply earnings per share by average P/E of comparable firms

forward p/e

to estimate the value of a firms share price, multiply earnings per share by average P/E of comparable firms

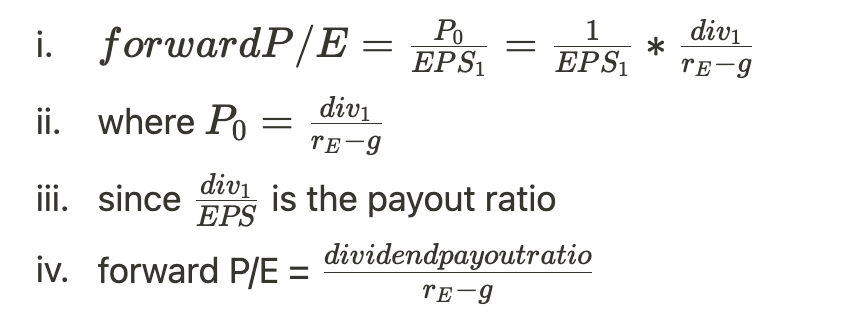

interpreting P/E ratio

if dividends grow at rate g forever then using the dividend model

p/e ratio depends on

equity cost of capital (ie the equity’s risk) → decreasing factor

growth rate → increasing factor

dividend payout ratio → increasing factor

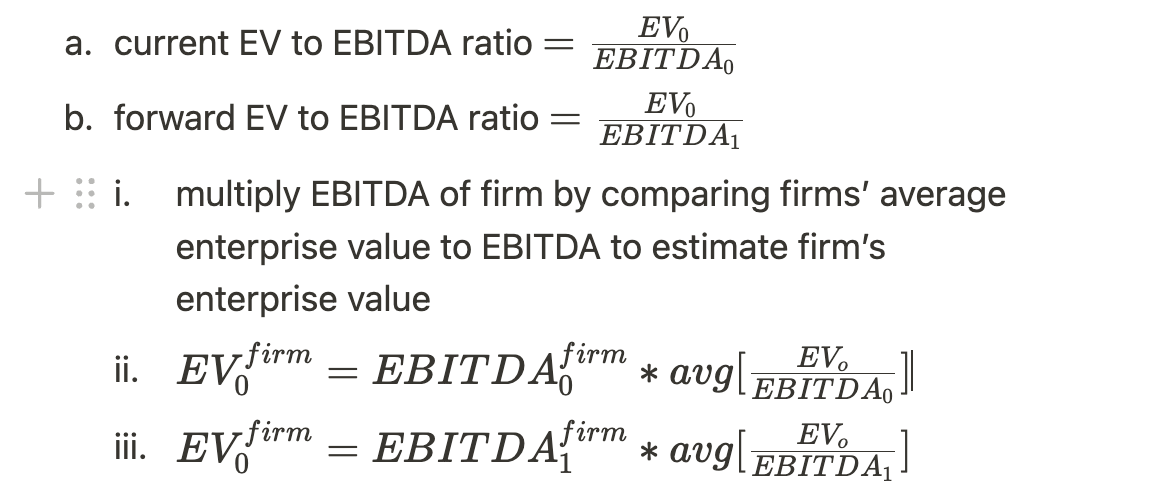

enterprise to EBITDA multiple

efficient markets hypothesis

implies that securities will be fairly priced based on their future cash flows given all publicly available info to investors