Genetics, Populations, Evolution and Ecosystems

1/118

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

119 Terms

Dominant and Recessive Alleles

In most cases, where two different alleles are present in the genotype, only one of them shows itself in the genotype. The allele of the heterozygote that expresses itself in the phenotype is said to be dominant, while the one that is not expressed is said to be recessive. A homozygous organism with two dominant alleles is called homozygous dominant, whereas one with two recessive alleles is called homozygous recessive. The effect of a recessive allele is apparent in the phenotype of a diploid organism only when it occurs in the presence of another identical allele.

Sex Chromosomes

In humans, the sex-chromosomes are X and Y. Females have two X chromosomes and so all the gametes are the same in that they contain a single X chromosome. Males have one X chromosome and one Y chromosome, so they produce different types of gamete; half have an X chromosome and half have a Y chromosome.

Genetic Cross Instructions

The instructions on how to construct a genetic cross are as follows:

- Use the symbols provided in the question with a single letter to represent each characteristic.

- Choose the first letter of one of the contrasting features, making it easy to identify which letter refers to which characteristic.

- If possible, choose a letter in which the higher and lower-case forms differ in shape and size to ensure that it will be almost impossible to confuse between the two.

- Let the higher case letter represent the dominant feature and the lower-case letter the recessive feature so they can be easily identified.

- Represent the parents with the appropriate pairs of letters, label them clearly as such and state their phenotypes to make it clear what the symbols refer to.

- State the gametes produced by each parent, label them and encircle them (This reinforces the idea that they are separate).

- Use a Punnett square to show the results of the random crossing of the gametes while still labelling the male and female gametes. This method is less liable to error than drawing lines between the gametes and the offspring.

- State the phenotypes of each different genotype and indicate the numbers of each type. Always put the dominant letter first when writing out the genotype, and this can reduce errors in cases where it is not possible to avoid using symbols with the higher and lower-case symbols letters of the same shape.

Monohybrid Inheritance

This is the inheritance of a single gene with two alleles. As an example, Gregor Mendel studied the colour of the pods of pea plants and saw that they came in the colours of green and yellow. If pea plants with green pods are bred repeatedly with each other so that they consistently give rise to plants with green pods, they are said to be pure-breeding for the character of green bods. This can be bred for almost any character, and it means that organisms are homozygous for that particular gene. If these pure-breeding green-pod plants are then crossed with pure-breeding yellow-pod plants, all the offspring, known as the first filial, or F1 generation, produce green pods, meaning the allele for green pods is dominant to the allele of yellow pods which is recessive.

When the heterozygous plants of the F1 generation are crossed with one another, the offspring (Known as the second filial) are always in an approximate ratio of three plants with green pods to each one plant with yellow pods. The larger the number of offspring, the more likely that the ratio will be 3:1, so if the sample is small, it is much less likely that the ratio will be 3:1.

Probability and Genetic Crosses

A ratio is a measure of the relative size of two classes expressed as a population. For easy comparisons, ratios are often obtained by dividing the value of the smallest group into the value of the larger group, and in this case all ratios have their smallest value as one.

Our knowledge of genetics tells us that for each cross, we would expect that, in the second filial, there would be three offspring showing the dominant feature to every one showing the recessive feature. However, in no case did Mendel obtain an exact 3:1 ratio. The same is true of almost any genetic cross, and these discrepancies are due to statistical error. It is chance that determines which gamete fuses with which.

The larger the sample, the more likely the actual results are to come near to matching the theoretical ones, and it is therefore important to use large numbers of organisms in genetic crosses if representative results are to be obtained. It is no coincidence that the two ratios nearest to the theoretical value of 3:1 in Mendel's experiments were with the largest sample size, whereas the ratio further from the theoretic value had the smallest sample size.

Dihybrid Inheritance

This involves how two characteristics, determined by two different genes located on different chromosomes, are inherited. In one of his experiments, Mendel investigated the inheritance of two characteristics of a pea plant at the same time. These were seed shape, where round shape is dominant to wrinkled shape, and seed colour, where yellow-coloured seeds are dominant to green-coloured ones. He carried out a cross between the two pure breeding types of plant: one always producing round-shaped, yellow-coloured seeds (Both dominant) and one always producing wrinkled-shaped, green-coloured seeds (Both recessive).

In the F1 generation, he obtained plants which all produced round-shaped, yellow-coloured seeds by crossing the two types, leading to the genotype of RrGg. This means that the plants of this generation can produce four types of gamete because the genes for seed colour and seed shape are on separate chromosomes. As the chromosomes arrange themselves at random on the equator during meiosis, any one of the two alleles of the gene for the seed colour can combine with any one of the alleles for seed shape. Fertilisation is also random, so that any of the four types of gamete of one plant can combine with any of the four types from the other plant. The theoretical ratio of 9:3:3:1 is close enough, allowing for statistical error, to Mendel's observed results of 315:108:101:32. His observations led him to formulate his law of independent assortment which means each member of a pair of alleles may combine randomly with either of another pair.

Codominance

This occurs where, instead of one allele being dominant and the other recessive, both alleles are equally dominant. This means that both alleles of a gene are expressed in the phenotype. One example occurs in shorthorn cattle in which one allele codes for an enzyme that catalyses the formation of a red pigment in hairs, and the other allele codes for an altered enzyme that lacks this catalytic activity and so does not produce the pigment, and so hairs are white. As they are codominant, in the heterozygous state, both coloured hairs are produced and so the coat is a light red, a colour also known as roan. If the shorthorn with a red coat is crossed with one with a white coat, the offspring will have a roan coat. The notation for this involves different letters, in this case R and W, and they are placed as superscripts on a letter that represents the gene.

If you are given a ratio of offspring that is different to the monohybrid (3:1) or dihybrid (9:3:3:1) ideals in a genetics question, you should consider that co-dominance might be the explanation.

Multiple Alleles

A gene that may have more than two alleles has multiple alleles, such as in ABO blood groups. There are three alleles associated with gene I which lead to the presence of different antigens on the cell-surface membrane of red blood cells: Allele IA leading to the production of antigen A, allele IB which leads to the production of antigen B, and allele IO which doesn't lead to the production of either. Although there are three alleles, only two can be present in an individual at any one time as there are only two homologous chromosomes and thus two gene loci. The alleles IA and IB are codominant, whereas the allele IO is recessive to both. There are obviously many different possible crosses between different blood groups, but two of the most interesting are:

- A cross between an individual of blood group O and one of blood group AB, rather than producing individuals of either of the parental blood groups, produces only individuals of the other two groups, A and B.

- When certain individuals of blood group A are crossed with certain individuals in blood group B, their children may have any of the four blood groups.

Sex-Linkage

Any gene that is carried on either the X or Y chromosome is said to be sex-linked. However, the X chromosome is much longer than the Y chromosome. This means that, for most of the length of the X chromosome, there is no equivalent homologous portion of the Y chromosome. Those characteristics that are controlled by recessive alleles on this non-homologous portion of the X chromosome will appear more frequently in the male because there is no homologous portion on the Y chromosome that might have been a dominant allele.

An X-linked genetic disorder may be caused by a defective gene on the X chromosome. One example in humans is haemophilia in which the blood clots slowly and there may be slow and persistent internal bleeding. As such, it is potentially lethal if not treated. This has resulted in some selective removal of the gene from the population, making its occurrence relatively rare. Although haemophiliac females are known, the condition is almost entirely confined to males.

One of the causes of haemophilia is a recessive allele with an altered sequence of DNA nucleotide bases that codes for a faulty protein which does not function, which results in an individual being unable to produce a functional protein that is required in the clotting process. The production of this functional protein by genetically modified organisms means that it can now be given to haemophiliacs, and this allows them to lead near-normal lives. It must be noted that the alleles are shown in the normal way in the Punnett square, but as they are linked to the X chromosome, they are not shown separately but are always attached to the X chromosome. There is no equivalent allele on the Y chromosome as it does not carry the gene for producing clotting protein.

As the defective allele that does not code for the clotting protein is linked to the X chromosome, males inherit the disease from their mother. If they mother does not suffer from the disease, she may be heterozygous for it. Such females are called carriers because they carry the allele without showing any signs of the disease in their phenotype. This is because these carriers possess one dominant H allele, and this leads to the production of enough functional clotting protein. As males pass the Y chromosome onto their sons, they cannot pass haemophilia to them, but they can pass the allele to their daughters, via their X chromosome, who would then become disease carriers.

Pedigree Charts

One useful way to trace the inheritance of sex-linked characteristics is to use a pedigree chart. In these, a male is represented by a square, a female is represented as a circle, and shading with either shape indicates the presence of a characteristic in the phenotype.

Autosomal Linkage

Any two genes that occur on the same chromosome are said to be linked, and all the genes on a single chromosome form a linkage group. The remaining 22 chromosomes, other than the sex chromosomes which are sex-linked, are called autosomes, and the name given to the situation where two or more genes are carried on the same autosome is called autosomal linkage. Assuming there is no crossing over, all the linked genes remain together during meiosis and so pass into gametes, and hence the offspring, together. They do not segregate in accordance with Mendel's Law of Independent Assortment.

When the two genes A and B with heterozygous alleles are on different chromosomes, there are four possible combinations of the alleles in the gametes, however if the two genes are linked and, provided there is no crossing over, there are only two possible combinations of the alleles in the gametes. For example, consider two linked genes of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster: one determines body colour and the other wing size. There are two alleles for body colour (One grey and dominant, one black and recessive) and there are also two alleles for wing size (One normal and dominant, other vestigial and recessive).

If the alleles for body colour and wing size were not linked but on separate chromosomes, an individual that is heterozygous for both characteristics would produce four different gametes rather than just two, as seen above. The offspring of this cross would therefore have the following characteristics - 9 grey and normal, 3 grey and vestigial, 3 black and normal, 1 black and vestigial.

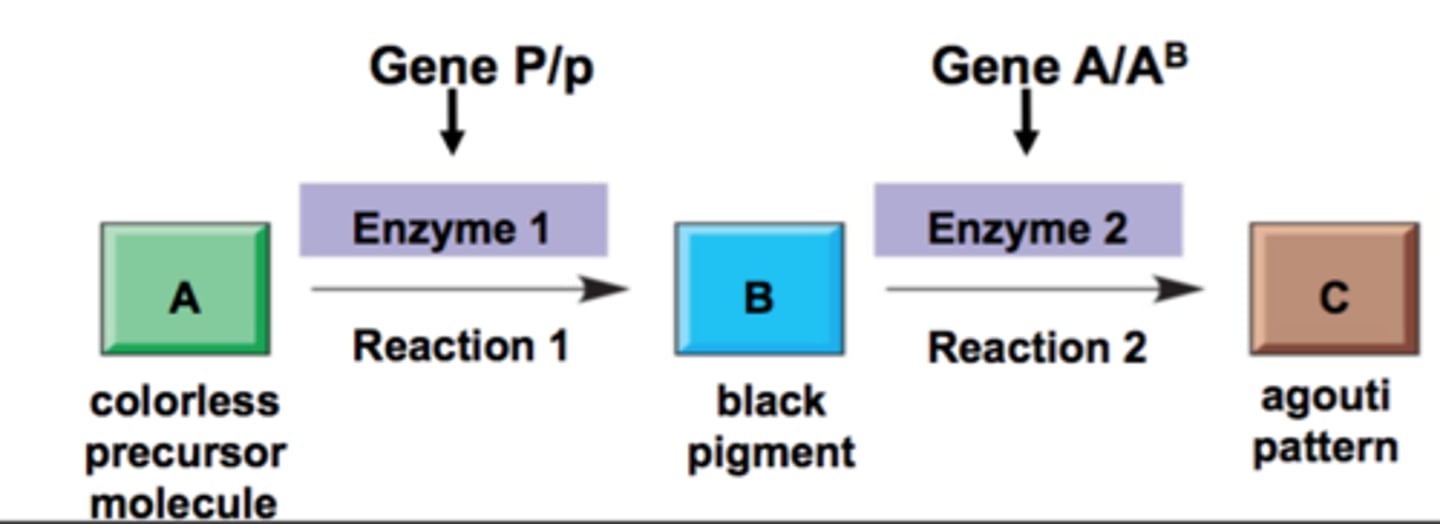

Epistasis

This arrives when the allele of one gene affects or masks the expression of another in the phenotype. An example occurs in mice where several genes determine coat colour:

- Gene A controls the distribution of a black pigment called melanin in hairs and therefore whether they are banded or not. The dominant allele A of this gene leads to hairs that have black bands while the recessive allele a produces uniform black hair.

- Gene B controls the colour of the coat by determining the expression of gene A. The dominant allele B leads to the production of melanin while the recessive allele b leads to no pigment and any hair will therefore be white when it is present with another recessive allele.

The usual mouse has a grey-brown coat known as agouti. This is the result of having hairs with black bands. If a mouse has uniform black hairs, its coat is black, and if the hairs lack melanin altogether, its coat is albino. Thus, if an agouti mouse with the genotype AABB is crossed with an albino mouse with the genotype aabb, the offspring will all be agouti. If the individuals from the F1 generation are crossed to produce the F2 generation, the following ratio is produced: 3 agouti mice, 4 albino mice and 3 black mice.

The explanation of the results is as follows:

- The expression of gene A is affected by the expression of gene B.

- If gene B is in the homozygous recessive state, no melanin is produced and the coat is albino.

- In the absence of melanin, gene A cannot be expressed. Therefore, regardless of which alleles are present, as there is no pigment, the hairs can be neither coloured nor banded.

- Where a dominant allele B is present, melanin is produced. If this allele is present with a dominant allele A, banding occurs and an agouti coat results. Where allele B is present with two recessive alleles, the hairs, and hence the coat, are uniform black.

Epistasis and Biochemical Pathways

There are other forms of epistasis, for example where genes act in sequence by determining the enzymes in a biochemical pathway. The production of enzymes A and B is coded for by genes A and B respectively. Dominant alleles of each gene code for a functional enzyme, while recessive alleles code for a non-functional enzyme. It follows that, if the alleles of either gene are both recessive, that enzyme will be non-functional and the pathway cannot be completed. This affects the gene in that, even if it is functional and produces its enzyme, its effects cannot be expressed because no pigment can be manufactured.

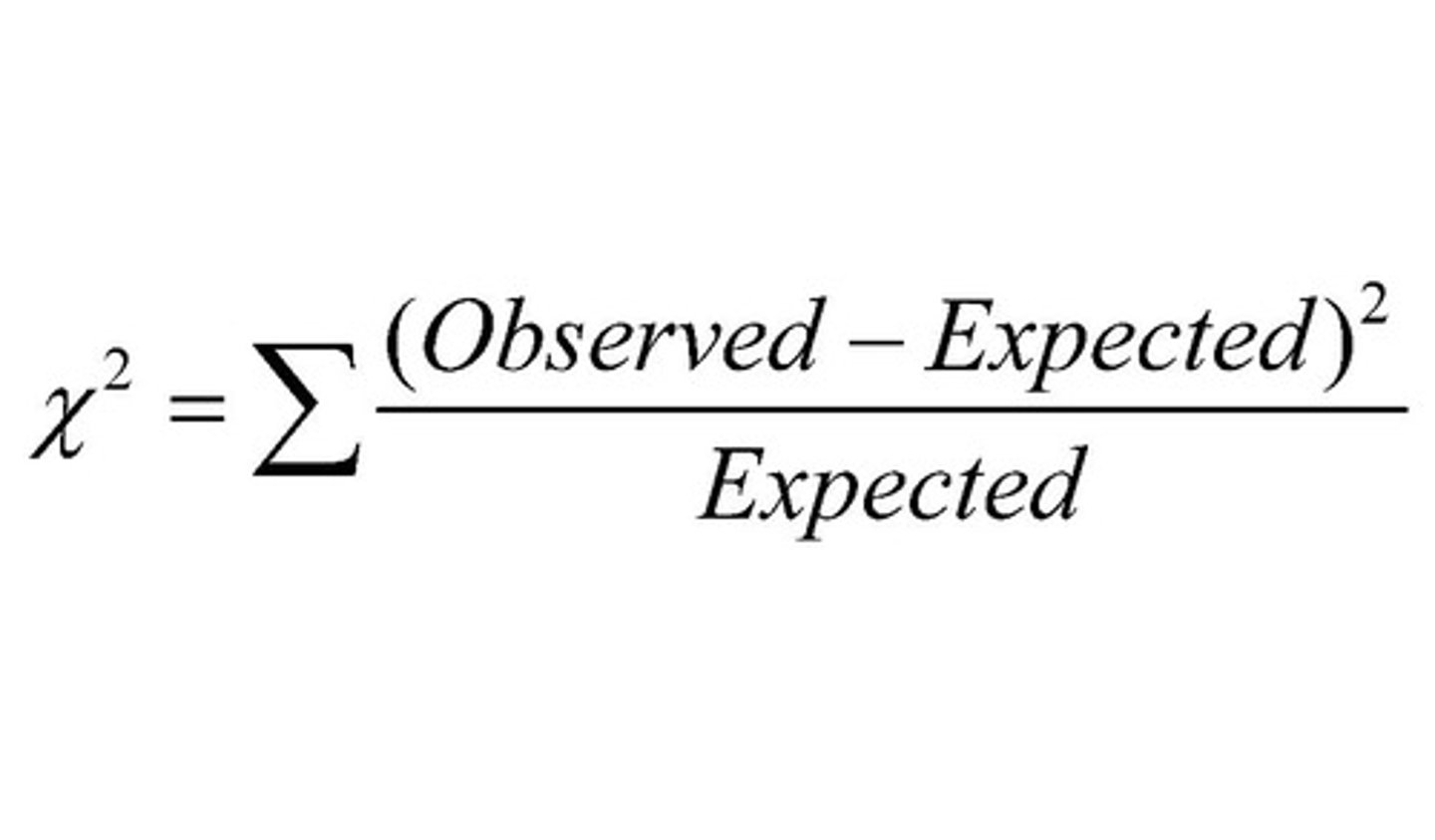

Chi-Squared in Genetics

This is used to test the null hypothesis. The null hypothesis is used to examine the results of scientific investigations and is based on the assumption that there will be no statistically significant difference between sets of observation, any difference being due to chance alone. The test is a means of determining whether any deviation between the observed and expected numbers in an investigation is significant or not. It is a simple test that can only be used if certain criterion is met:

- The sample size must be relatively large (Over 20).

- The data must fall into discrete categories.

- Only raw counts can be used.

- It is used to compare experimental results with theoretical ones.

- It compares frequencies of people/items in categories.

For genetics, if your theory is correct, the null hypothesis will be accepted, meaning the expected ratio, and if you reject it, something else must be going on.

The value obtained is then read off a chi-squared distribution table to determine whether any deviation from the expected results is significant or not. To do this we need to know the number of degrees of freedom which is simply the number of classes minus one. If the probability that the deviation is due to chance is equal to or greater than 0.05, the deviation is said to not be significant and the null hypothesis would be accepted. If the deviation is less than 0.05, the deviation is said to be significant. In other words, some factor other than chance is affecting the results and the null hypothesis must be rejected.

Population Genetics

All the alleles of the genes of everyone in a population at a given time is known as the gene pool, and the number of times an allele occurs within the gene pool is referred to as allelic frequency.

An example of a gene that has two alleles (One recessive and one dominant) is the gene for cystic fibrosis, a disease of humans in which the mucus produced by affected individuals is thicker than normal. The gene has a dominant allele that leads to normal mucus production and a recessive allele that leads to the production of thicker mucus and hence cystic fibrosis. Any individual human has two of these alleles in every one of their cells, one on each of the pair of homologous chromosomes on which the gene is found. As these alleles are the same in every cell of a single person, we only count one pair of alleles per gene per individual when considering a gene pool. Thus, if there are n people in a population, there will be 2n alleles in the gene pool.

The pair of alleles of the cystic fibrosis gene has three different possible combinations, namely homozygous dominant, homozygous recessive and heterozygous. When we look at allele frequencies however, it is important to appreciate that the heterozygous combination can be written as Ff or fF.

In a population of 10,000 people, if everyone had the genotype FF then the frequency of the F allele would be 100%, but if everyone in our population was heterozygous, the probability of anyone being Ff would be 1.0 and the frequency of both alleles would be 50%. Of course in practice, the population is made up of a mixture of all three genotypes, and the proportions of this can vary between populations.

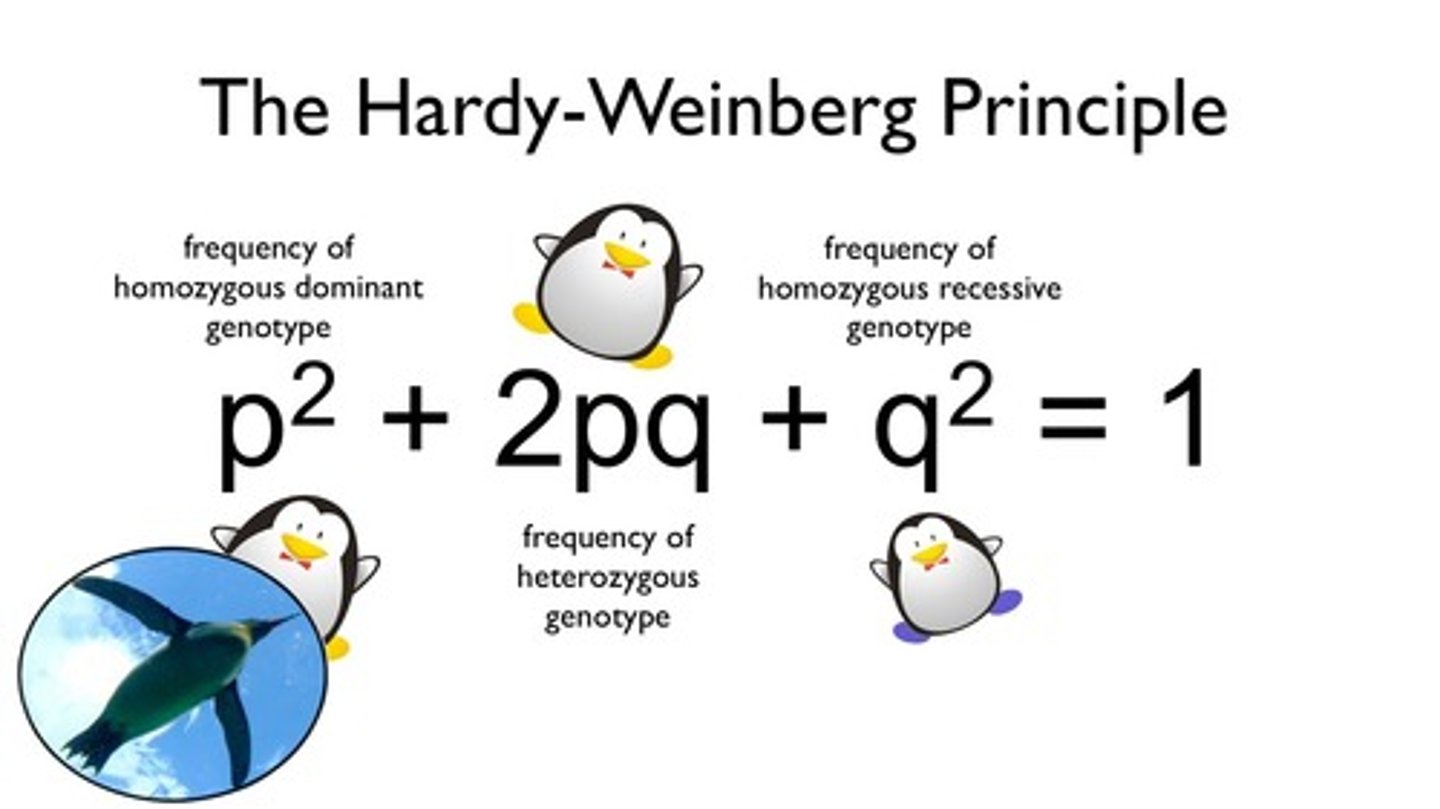

The Hardy-Weinberg Principle

This provides a mathematical equation that can be used to calculate the frequencies of the alleles of a particular gene in a population. The principle makes the assumption that the proportion of dominant and recessive alleles of any gene in the population remains the same from one generation to the next. This can be the case provided that five conditions are met: No mutations arise, the population is isolated (No flow of alleles into or out of the population), no selection (All alleles are equally likely to be passed to the next generation), and the population is large and random. Although these conditions are probably never totally met in a natural population, the principle is still useful when studying gene frequencies.

To understand the principle, consider a gene that has two alleles: One dominant and one recessive. Let the probability of allele A = p and the probability of allele a = q, so p + q = 1.0 because there are only two alleles. As there are only four possible arrangements of the two alleles, it follows that the probability of all four added together must equal 1.0.

Variation due to Genetic Factors

Within a population, all members have the same genes. However, genetic differences occur as members of this population will have different alleles of these genes. These differences not only occur in living individuals, but also change from generation to generation. Genetic variation arises as a result of all of the following methods:

- Mutations - These sudden changes to genes and chromosomes may, or may not, be passed on to the next generation. They are the main source of variation.

- Meiosis - This special form of nuclear division produces new combinations of alleles before they are passed into the gametes, all of which are therefore different.

- Random fertilisation of gametes - In sexual reproduction, this produces new combinations of alleles and the offspring are therefore different from parents. Which gamete fuses with which at fertilisation is a random process, further adding to the variety of offspring.

Where variation is very largely the result of genetic factors, organisms fit into a few distinct forms and there are no intermediate types. In the ABO blood grouping system for example, there are four distinct groups, and it is usually controlled by a single gene. Environmental factors have little influence of this type of variation. Variation where organisms fit into a few distinct forms is known as discontinuous variation and can be represented on a bar chart or pie graph.

Variation due to largely Environmental Influences

Environmental influences affect the way the organism's genes are expressed. The genes set limits, but it is largely the environment that determines where within those limits an organism lies. For example with plants, environmental influences include climactic conditions, soil conditions, pH and food availability.

Some characteristics of organisms grade into one another, forming a continuum. In humans, two examples are height and mass. Characters that display this type of variation are not controlled by a single gene, but by many genes (Polygenes). Environmental factors play a major role in determining where on the continuum an organism actually lies. For example, individuals who are genetically predetermined to be the same height actually grow to different heights due to variations in environmental factors such as diet. This type of variation is the product of polygenes and the environment. If we measure the heights of a large population of people and plot the number of individuals against heights on a graph, we will most probably obtain a normal distribution curve.

In most cases, variation is due to the combined effects of genetic differences and environmental influences. It is very hard to distinguish between the effects of the many genetic and environmental influences that combine to produce differences between individuals. As a result, it is very difficult to draw conclusions about the causes of variation in any particular case. Any conclusions that are drawn are usually tentative and should be treated with caution.

Selection Pressures

Every organism is subjected to selection based on its suitability for survival under the conditions that exist at the time. The environmental factors that limit the population of a species are called selection pressures, which include predation, disease and competition, and they vary between time and place. These pressures determine the frequency of all alleles within the gene pool.

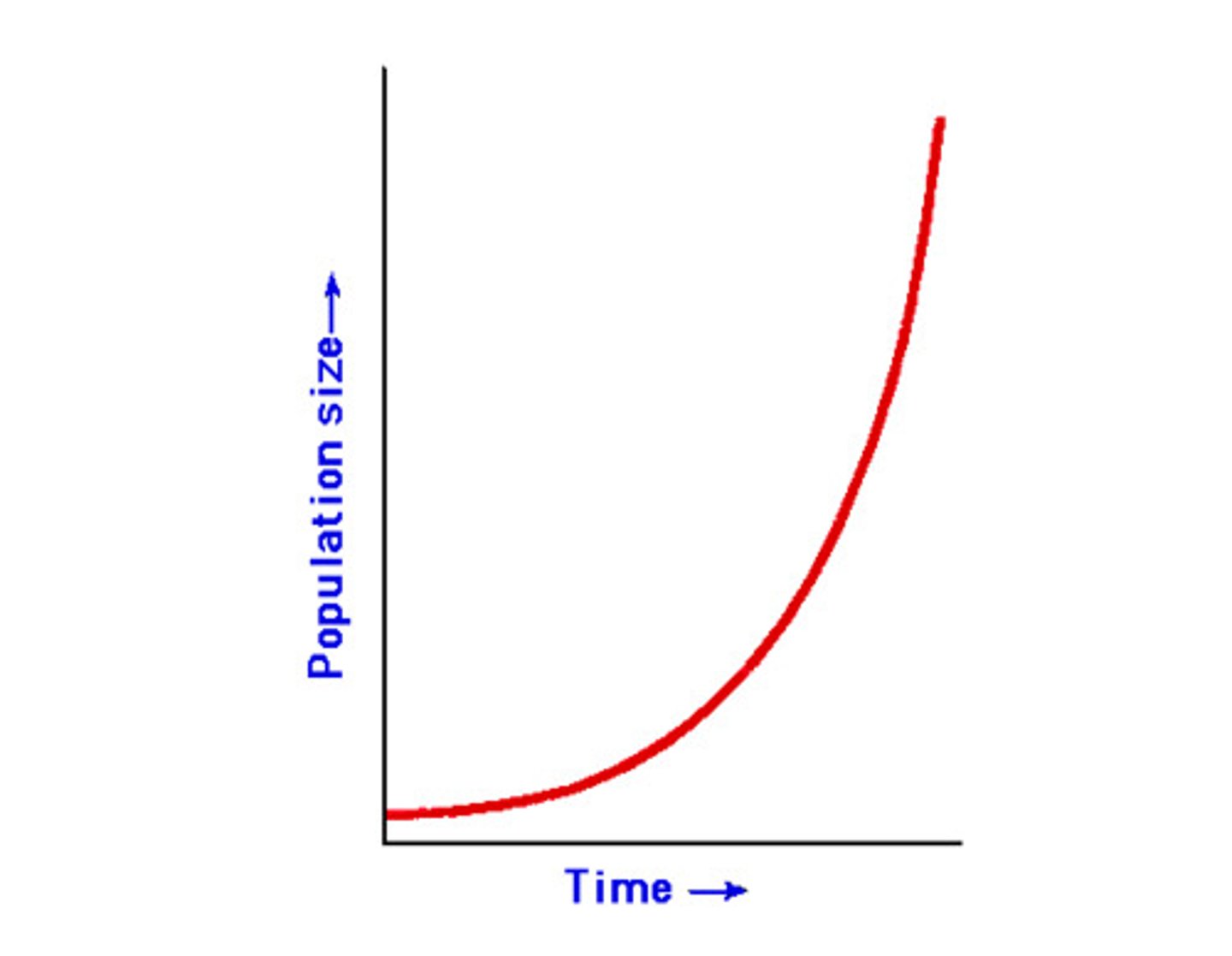

The Role of Over-Production in Natural Selection

Darwin appreciated that all species have the potential to increase their numbers exponentially, but he realised that, in nature, populations rarely, if ever, increased in size at such a rate. He rightly concluded that the death rate of even the most slow-breeding species must be extremely high. High reproductive rates have evolved in many species to ensure a sufficiently large population survives to breed and produce the next generation which compensates for high death rates from predation, competition for resources, extremes of temperature, natural disasters, disease etc. On the other hand, some species have evolved lower reproductive rates along with a high degree of paternal care, and the lower death rates that result help to maintain their population size.

The link between over-production and natural selection lies in the fact that, where there are too many offspring for the available resources, there is intraspecific competition among individuals. The greater the numbers, the greater this competition and the more individuals that die in the struggle to survive. However, these deaths are not completely random. Those individuals in a population best suited to prevailing conditions will be more likely to survive than those less well adapted, meaning they will be more likely to breed and so pass their more favourable allele combinations to the next generation, meaning they will have a different allele frequency to the previous one. The population will have evolved a combination of alleles that is better adapted to the prevailing conditions, but this selection process depends on individuals in a population being genetically different from each other.

The Role of Variation in Natural Selection

If an organism can survive in the conditions in which it lives, in theory it should produce offspring that are identical to itself as the offspring will be equally likely to survive in these conditions, whereas variation may produce individuals that are less suited. However, conditions change over time and having a wide range of genetically different individuals in a population means that some will have the combination of genes needed to survive in almost any new set of circumstances. Populations showing little individual genetic variation are often more vulnerable to new diseases and climate change, and it is important that a species is capable of adapting to changes resulting from the evolution of other species.

The larger the population is, and the more genetically varied the individuals within it, the greater the chance that one or more individuals will have the combination of alleles that lead to a phenotype which is advantageous in the struggle for survival. These individuals will therefore be more likely to breed and pass their allele combinations on to future generations, and so variation provides the potential for a population to evolve and adapt to new circumstances.

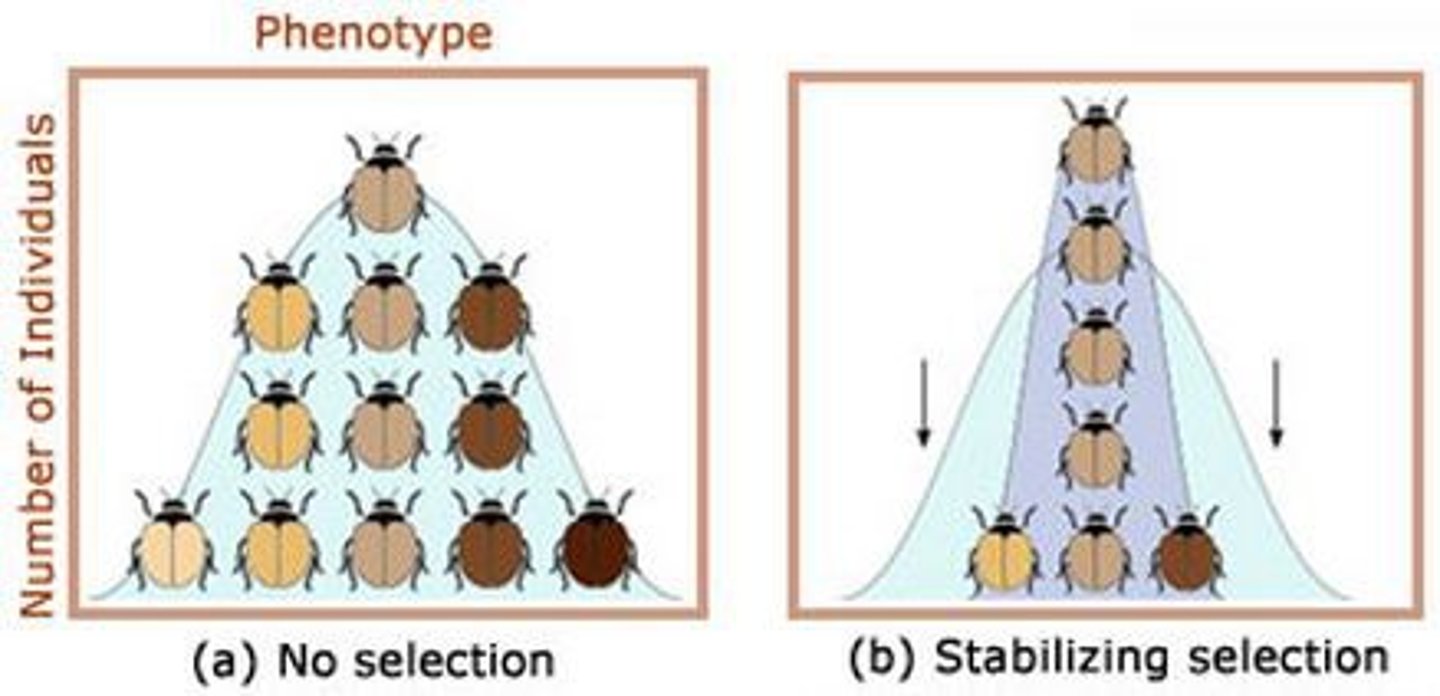

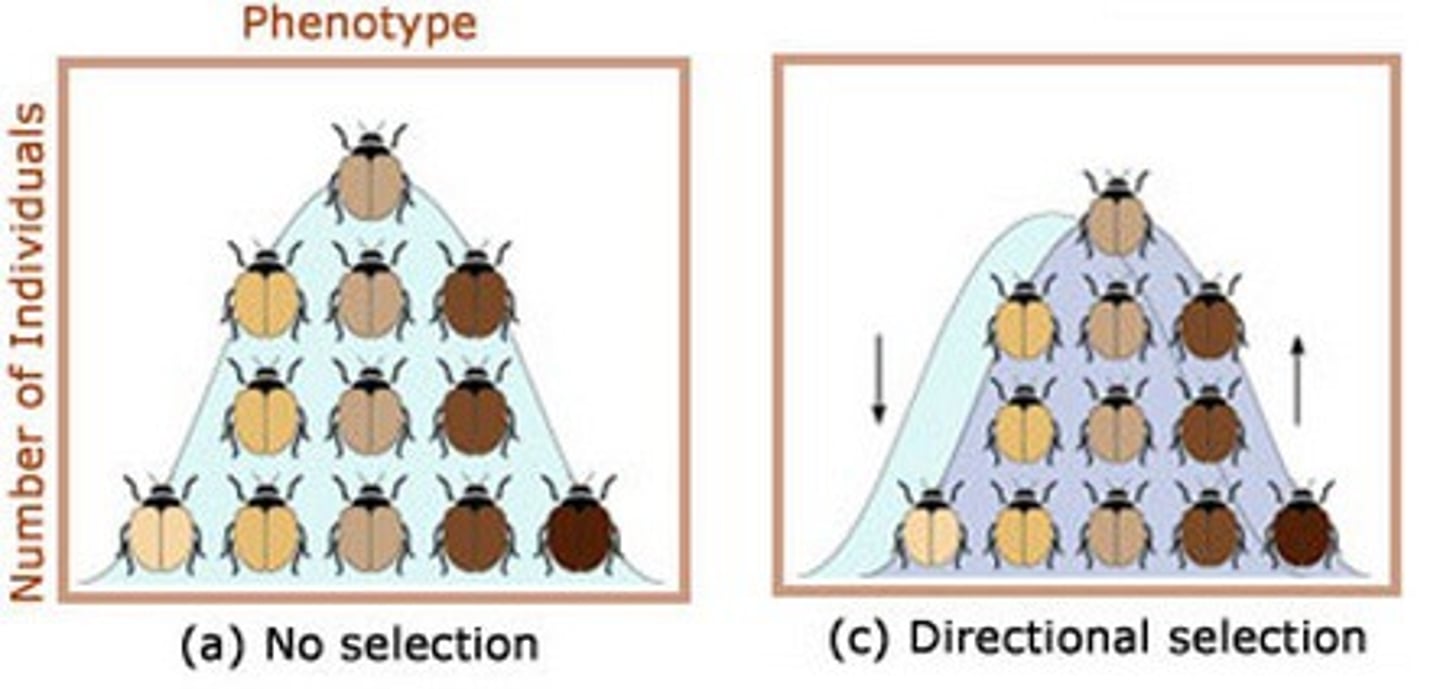

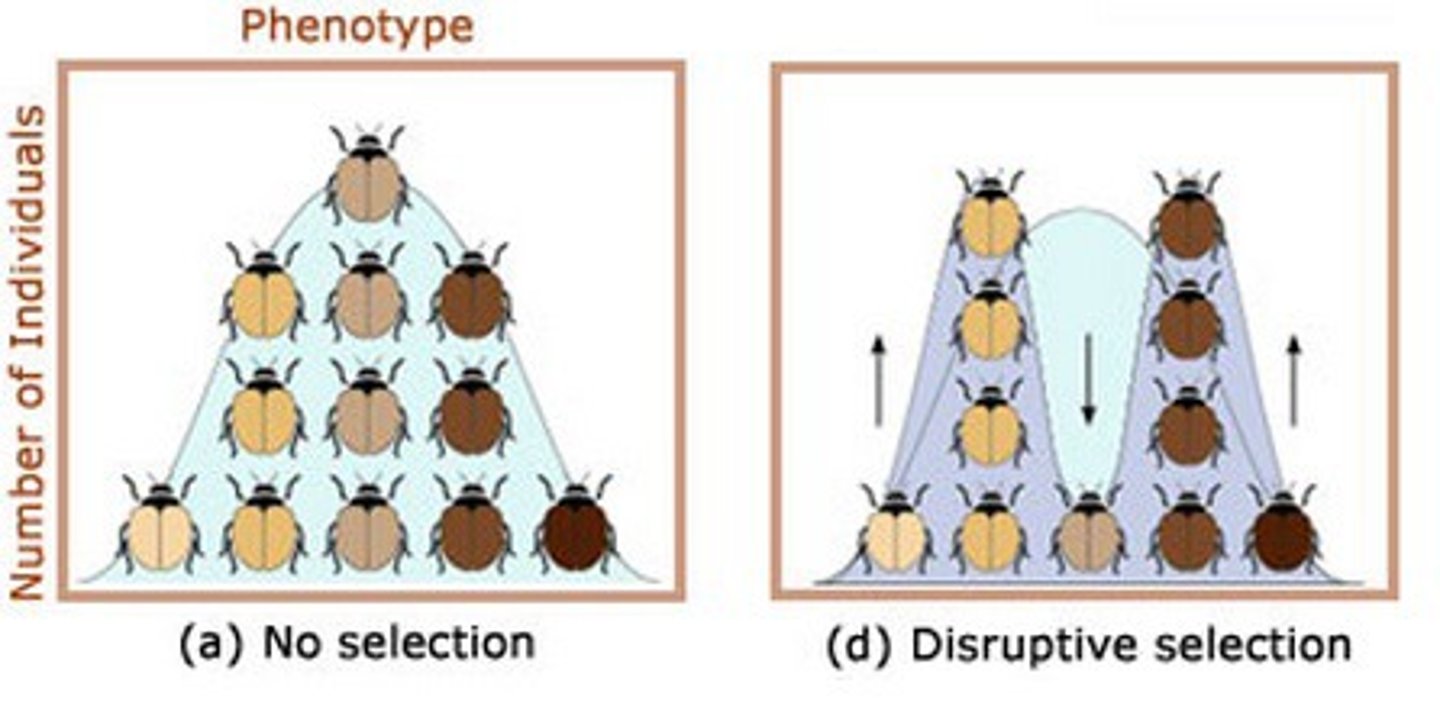

Types of Selection

- Stabilising selection preserves the average phenotype of a population by favouring average individuals; this is selection against the extreme phenotypes.

- Directional selection changes the phenotypes of a population by favouring phenotypes that vary in one direction from the mean of the population; this is selection for one extreme.

- Disruptive selection favours individuals with extreme phenotypes rather than those phenotypes around the mean of the population.

Stabilizing Selection in relation to Phenotypes

This tends to eliminate the extremes of a phenotype range within a population, and with it, the capacity for evolutionary change. It tends to occur where the environmental conditions are constant over a long period of time. One example is fur length; in years where the environmental conditions are hotter than usual, the individuals with shorter fur length will be at an advantage because they can lose body heat more rapidly, but in colder years the opposite is true, and so those with longer fur length will survive better due to better insulation. Therefore, if the environment fluctuates from year to year, both extremes will survive because each will have some years where it can thrive at the expense of the other. However, if the environmental temperature is constantly 10 degrees, individuals at the extremes will never be at an advantage and will therefore be selected against in favour of those with average fur length. The mean will remain the same, and there will be fewer individuals at either extreme.

Directional Selection in relation to Phenotypes

Within a population, there will be a range of genetically different individuals. This continuous variation amongst these individuals forms a normal distribution curve which has a mean representing the optimum value for the phenotypic characteristic under the existing conditions. If the environmental conditions change, so will the optimum value for survival. Some individuals, either to the left or the right of the mean, will possess a combination of alleles with the new optimum for the phenotypic characteristic. As a result, there will be a selection pressure favouring the combination of alleles that results in the mean moving to either the left or the right of its original position. Directional selection therefore results in one extreme of a range of variation being selected against in favour of the other extreme or even the average.

Disruptive Selection in relation to Phenotypes

This is the opposite of stabilising selection as it favours extreme phenotypes at the expense of the intermediate phenotypes. Although it is the least common form of selection, it is most important in bringing about evolutionary change. Disruptive selection occurs when an environmental factor takes two or more distinct forms. In our example, this might arise if the temperature alternated between 5 degrees in winter and 15 degrees in summer. This could ultimately lead to two separate species of the mammal: One with long fur and active in winter, the other with short fur and active in summer. The animals with the allele in between these two will be no better adapted than either population at each extreme, and so they will be selected against.

Allelic Frequencies and How Selection Affects Them

In theory, any sexually mature individual in a population is capable of breeding with any other. This means that the alleles of any individual organism may be combined with the alleles of any other. The allelic frequency is affected by selection, and selection is due to environmental factors. Environmental changes therefore affect the probability of an allele being passed on in a population and hence the number of times it occurs within a gene pool. It must be emphasised that environmental factors do not affect the probability of a particular mutant allele arising; they simply affect the frequency of a mutant allele that is already present in the gene pool. Evolution by natural selection is thus a change in the allelic frequencies within a population.

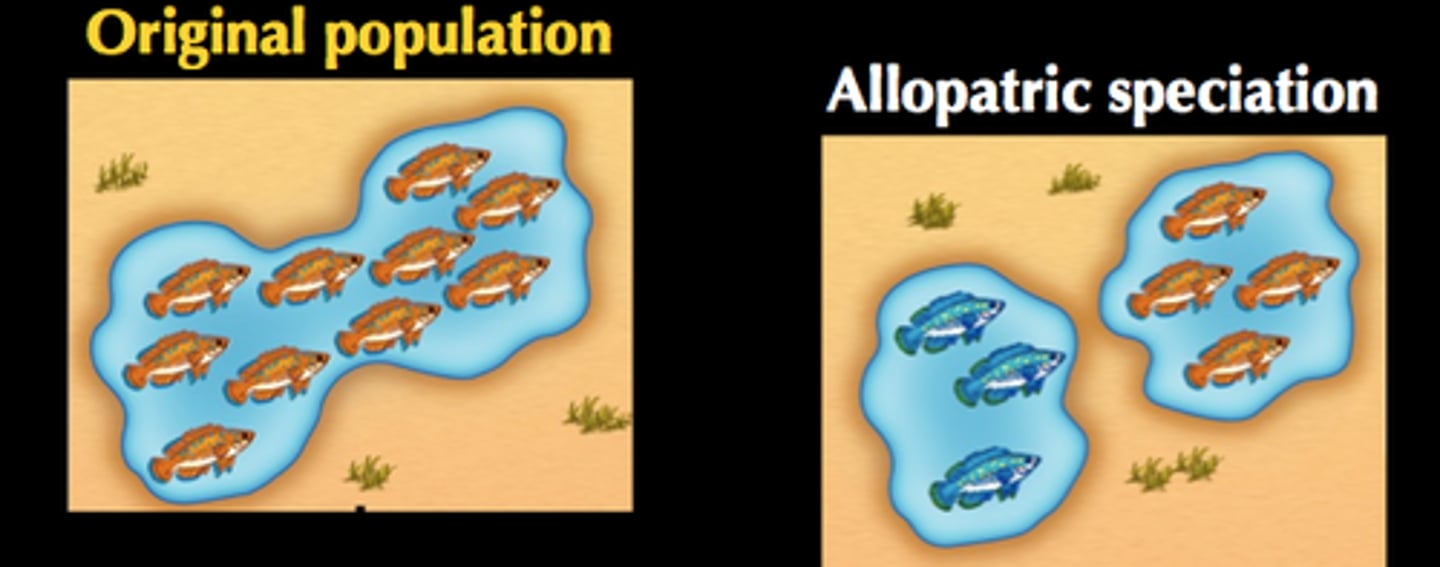

Speciation

This is the evolution of new species from existing ones. A species is a group of individuals that have a common ancestry and so share the same genes, but different alleles, and are capable of breeding with one another to produce fertile offspring. In other words, members of a species are reproductively separated from other species. It is through the process of speciation that evolutionary change has taken place over millions of years, resulting in great diversity.

By far the most important way in which new species are formed is through reproductive separation followed by genetic change due to natural selection. Within a species, there are one or more populations, and although individuals tend to breed only with others in the same population, they are capable of breeding with individuals in other populations.

Suppose that a population becomes separated in some way from other populations and undergoes different mutations. Each of the populations will experience different selection pressures because the environment of each will be slightly different. Natural selection will then lead to changes in the allelic frequencies of each population. The different phenotypes each combination of alleles produces will be subject to selection pressure that will lead to each population becoming adapted to its local environment. This is known as adaptive radiation and results in changes to the allele frequencies of each population. In other words, each population evolves. As a result of these genetic differences, it may be that, even if the populations were no longer physically separated from one another, they would be unable to interbreed successfully. Each population would now be a different species each with their own gene pool.

Genetic Drift

This is the idea that, through chance, some individuals will leave behind more descendants than others, leading to a shift in the allele frequency of the population. This will have a greater effect on smaller populations which already have a very small gene pool, when in larger populations it is likely that the allele will still remain in a large frequency even when it occurs.

Allopatric Speciation

Allopatric means different countries and describes the form of speciation where two populations become geographically separated. This may be the result of any physical barrier between two populations which prevents them from interbreeding, including oceans etc. Of course, what proves a barrier to one species may be no problem to another. If environmental conditions either side of the barrier vary, natural selection will influence the two populations differently, and each will evolve, leading to adaptations to their local conditions. These changes may take many hundreds or even thousands of generations, but ultimately may lead to reproductive separation of separate species.

An example of this is the Galapagos finch. A single species is thought to have colonised one of the Galapagos islands, and in the absence of competition, its population increased and populations become established on the same and different islands which each population evolving adaptations to suit its new environment, including different shapes and sizes of beak to deal with different seed times. Being geographically separated, the changes have led to the populations becoming so different overtime that they can no longer interbreed, and thus new species have been formed.

Sympatric Speciation

Sympatric means same country and describes the form of speciation that results within a population in the same area leading to them becoming reproductively separated due to various types of barriers to successful mating.

An example of this is with the Apple Maggot Fly. Originally, this insect only laid its eggs inside the fruit of hawthorns which are native to North America. When apple trees were introduced, the fly started to lay its eggs in apples also. Females tend to lay their eggs on the type of fruit in which they developed and males tend to look for mates on the type of fruit in which they developed. So, flies raised in the same area will tend to mate with each other. While the two types are not separate species, mutations in each population have led to the evolution of genetic differences and thus a change in the allele frequency of the two populations, and in time this could result in them being incapable of successfully breeding with each other to produce fertile offspring.

Types of Isolating Mechanisms:

- Geographical - Populations are isolated by physical barriers.

- Ecological - Populations inhabit different habitats within the same area and so individuals rarely meet each other.

- Temporal - The breeding seasons of each population do not coincide and so they do not interbreed with each other.

- Behavioural - Mating is often preceded by courtship, and this is stimulated by the colour or markings of the opposite sex, the call or particular actions of a mate. Any mutations which cause variations in these patterns may prevent mating.

- Mechanical - Anatomical differences may prevent mating from occurring.

- Gametic - The gametes may be prevented due to genetic or biochemical incompatibility.

- Hybrid Sterility - Hybrids formed from the fusion of gametes from different species are often sterile because they cannot produce viable gametes.

Ecology

This is the study of the inter-relationships between organisms and their environment. The environment includes both non-living factors, such as temperature and rainfall, and living factors, such as competition and predation.

Ecosystem

These are dynamic systems made up of a community and all the non-living factors of its environment. Ecosystems can range in size from very small to very large. Within an ecosystem, there are two major processes to consider:

- The flow of energy through the system.

- The cycling of elements within the system.

An example of an ecosystem is a freshwater pond or lake. It has its own community of plants to collect the necessary light energy to supply the organisms within it. Nutrients such as nitrate and phosphate ions are recycled within the pond or lake. This is little or no loss or gain between it and other ecosystems.

Population

This is a group of individuals of one species that occupy the same habitat at the same time and are potentially able to interbreed. An ecosystem supports a certain size of population of a species called the carrying capacity. The size of the population can vary as a result of the effect of abiotic factors, and interactions between organisms including intra/interspecific competition and predation. In the different habitats of oak woodland for example, there are populations of nettles, worms, beetles etc. The boundaries of a population are often difficult to define.

Community

This is all of the populations of different species living and interacting in a particular place at the same time. Within an oak woodland, the community may include a large range of organisms such as oak trees, fungi etc.

Habitats and Microhabitats

This is the place where an organism normally lives and is characterised by physical conditions and the other types of organisms present. Within an ecosystem, there are many habitats; for example, with an oak woodland, the leaf canopy of trees may be the habitat for blue tits while a decaying log is the habitat for woodlice. Within each habitat, there are smaller units, each with their own microclimate. These are called microhabitats. For example, the mud at the bottom of the stream may be a microhabitat for a bloodworm while a crevice.

Niches and Niche Differentiation

This describes how an organism fits into the environment (The role or function of an organism or species in an ecosystem). It refers to where an organism normally lives and what it does there. It includes all the conditions to which an organism is adapted in order to survive, reproduce and maintain a viable population. Some species may appear very similar, but their nesting habits or other aspects of their behaviour will be different, or they may show different levels of tolerance to environmental factors, such as a pollutant or a shortage of oxygen or nitrates. No two species occupy the same niche, and this idea is known as the competitive exclusion principle.

Two species of plants may be able to tolerate different temperatures and different pH levels, and so they avoid direct competition by occupying different niches. This is called niche differentiation.

Plotting Growth Curves

The number of individuals in a population is the population size. Populations are dynamic in that they vary in size and composition over time. Where a population grows in size slowly over a period of time, it is possible to plot a graph of numbers in a population against time. Where a population grows rapidly over a short period of time however, this may not be possible. Consider a set of data which shows the increase in population size of a bacterium that generally doubles its number each hour. Plotting a graph of these numbers against time means that the curve will run off the graph after a low period of time. In these cases, it is necessary to use a logarithmic scale to represent the number of bacteria. When the graph of log bacterial numbers is plotted against time, all points can be represented on a graph and we will be able to see when the rate of growth starts to slow.

Temperature as an Abiotic Factor

Each species has a different optimum temperature at which it is best able to survive. The further away from this optimum, the fewer the individuals in the population are able to survive and the smaller the population that can be supported. In plants and cold-blooded animals, as temperatures fall, enzymes work more slowly and so their metabolic rate is reduced, and populations therefore have a smaller carrying capacity. At temperatures above the optimum, the enzymes work less efficiently because they gradually undergo denaturation. Again, the population's carrying capacity is reduced. Warm-blooded animals, such as birds and mammals, are able to maintain a relatively constant body temperature regardless of the external temperature, so it could be seen that their carrying capacity would be unaffected by temperature change. However, the further the external temperature gets from the optimum, the more energy these organisms expend in trying to maintain their normal body temperature, leaving less energy for individual growth so they mature slower and their reproductive rate slows, so the carrying capacity of this population is also reduced.

Light as an Abiotic Factor

The rate of photosynthesis increases as light intensity increases. The greater the rate of photosynthesis, the faster plants grow and the more spores or seeds they produce, and so their carrying capacity is potentially greater. In turn, the carrying capacity of animals that feed on plants could potentially be larger.

pH as an Abiotic Factor

This affects the action of enzymes, and each enzyme has an optimum pH at which it operates most effectively. A population of organisms is larger where the appropriate pH exists, and smaller or non-existent where the pH is different from the optimum.

Water and Humidity as Abiotic Factors

Where water is scarce, populations are small and consist only of species that are adapted to living in dry conditions. Humidity affects the transpiration rate of plants and the evaporation of water from animals. Again, in dry air conditions, the populations of species adapted to tolerate low humidity will be larger than those with no such adaptations.

List of Abiotic Factors

Temperature, Light, pH, water, humidity, moisture content of soil, wind, latitude, soil composition, salinity, radiation, pollution, space, water retaining capacity.

In general terms, when any abiotic factor is below the optimum for a population, fewer individuals are able to survive because their adaptations are not suited to the conditions. If no individuals have adaptations that allow survival, the population becomes extinct.

Human Population Growth Rate

For human populations, the basic factors that affect the growth and size of them are birth rate, death rate, immigration and emigration. The equation to find the population growth is:

Population Growth - (Birth Rate + Immigration) - (Death Rate + Emigration).

To show how a factor influences the size of a population, it is necessary to link it to the birth rate and death rate of individuals in a population. For example, an increase in food supply does not necessarily mean there will be more individuals as it could just result in bigger individuals. It is therefore important to show how one factor affects the number of individuals in a population. For example, a decrease in food supply could lead to individuals dying of starvation leading to a direct reduction in the size of a population. An increase in food supply means that more individuals are likely to survive, and so there is an increased probability that they will produce offspring, leading to the population increasing. This effect therefore takes longer to influence population size.

Types of Population

- Stable - Birth and death rate are in balance.

- Increasing - High birth rate and immigration along with fewer older people. This type is typical of less economically developed countries.

- Decreasing - Lower birth rate and emigration along with a lower mortality rate meaning more elderly people. This type is typical in more economically developed countries.

Competition

This is where two or more individuals share any resources that are insufficient to satisfy all their requirements fully, competition will occur. Where such competition arises between members of the same species, it is called intraspecific competition, and where it arises between members of different species, it is termed interspecific competition.

Intraspecific Competition

This occurs when individuals of the same species compete with one another for resources, and it is the availability of such resources that determines the size of a population. An example of this type of competition is robins competing for breeding territory. Female birds are normally only attracted to males who have established territories. Each territory provides adequate food for one family of birds, but when food is scarce, territories become larger to provide enough food. There are therefore fewer territories in a given area and fewer breeding pairs, leading to a smaller population size.

Interspecific Competition

This occurs when individuals of different species compete for resources. When populations of two species are in competition with one another, one will normally have a competitive advantage over the other. The population of this species will gradually increase in size while the population of the other will diminish. If conditions remain the same, this will lead to the complete removal of one species due to the competitive exclusion principle. This states that where two species are competing for limited resources, the one that uses them more effectively will ultimately eliminate the other. This means that no two species can occupy the same niche indefinitely when resources are limiting. While two species can appear to occupy the same niche, analysis of their food will likely show that they feed on different items, and so they do in fact occupy a different niche.

Predation

As predators have evolved, they have become better adapted for capturing their prey as they may have faster movement, more effective camouflage, better means of detecting their prey etc. Simultaneously, prey have equally become more adept at avoiding predators, such as having better camouflage, more protective features, concealment behaviour etc.

Predation occurs when one organism is consumed by another. When a population of a predator and a population of its prey are brought together in a laboratory, the prey is usually exterminated, largely because the range and variety of the habitat provided is limited to the confines of the laboratory. In nature, the situation is different. The area over which the population can travel is far greater and the variety of the environment is much more diverse. In particular, there are many more potential refuges. In these circumstances, some of the prey can escape predation because the fewer there are, the harder they are to find. Therefore, although the prey population falls to a low level, it rarely becomes extinct.

Caution with Lab Evidence with Predation

Evidence collected on predator and prey populations in a laboratory does not necessarily reflect what happens in the wild. At the same time, it is difficult to obtain reliable data on natural populations because it is not possible to count all of the individuals, and so its size can only be estimated from sampling and surveys. None guarantee complete accuracy, and we must therefore treat all data produced in this way with caution.

The Relationship between Predators and Prey and Their Effect on Population Size

- Predators eat their prey, reducing the population of it.

- With fewer prey available, the predators are in greater competition with each other for the prey that is left.

- The predator population is reduced as some individuals are unable to obtain enough prey for their survival.

- With fewer predators left, less prey is eaten and so more survive and reproduce, leading to an increase in the prey population.

- With more prey available as food, the predator population increases.

In natural ecosystems however, organisms eat a range of foods and therefore the fluctuations in population size are often less severe. Although predator-prey relationships are significant reasons for cyclic fluctuations in populations, they are not the only reasons as disease and climatic factors also play a part. These periodic population crashes are important in evolution as there is a selection pressure which means that those individuals who are able to escape predators, or withstand disease/an adverse climate, are more likely to survive and reproduce. The population therefore evolves to be better adapted to the prevailing conditions.

Principles of Investigating Populations

To study a habitat, it is often necessary to count the number of individuals of a given species in a given space. It is virtually impossible to identify and count every organism as it would be time-consuming and would almost certainly cause damage to the habitat being studied. For this reason, only small samples of the habitat are usually studied in detail. To obtain reliable results, it is necessary to ensure that the sample size is large (Many quadrats are used) and the mean of all the samples is obtained. The larger the number of samples, the more representative the results will be of the community as a whole.

Types of Quadrat

- Point Quadrat - Consists of a horizontal bar supported by two legs. At set intervals along the horizontal bar are ten holes, through each of which a long pin may be dropped. Each species that the pin touches is then recorded. This is a more objective way to record percentage cover than a frame quadrat.

- Frame Quadrat - A square frame divided into equally sized subdivisions. The quadrat is placed in different locations within the area being studied. The abundance of each species within the quadrat is then recorded.

Factors to Consider when Using Quadrats

- The size of the quadrat to use - This will depend on the size of the plants or animals being counted and how they are distributed within the area. Where a population of species is not evenly distributed throughout the area, a large number of small quadrats will give more representative results than a small number of large ones.

- The number of sample quadrats to record within the study area - The larger the number of sample quadrats, the more reliable the results. As the recording of species within a quadrat is a time-consuming task, a balance needs to be struck between the reliability of the results and the time available. The greater the number of different species present in the study area, the greater the number of quadrats required to produce reliable results for a valid conclusion.

- The position of each quadrat within the study area - To produce statistically significant results, random sampling must be used.

Random Sampling with Quadrats

To obtain a random sample, you could stand in an area and throw the quadrat over your shoulder, but there is a better method for this:

1. Lay out two long tape measures at right angles along two sides of the study area.

2. Obtain a series of coordinates by using random numbers from a table/generated by a computer.

3. Place a quadrat at the intersection of each pair of coordinates and record the species within it.

Systematic Sampling along Belt Transects

It is sometimes more informative to measure the abundance and distribution of a species in a systematic manner. This is particularly important where some form of gradual change in the communities of plants and animals takes place across a distance. One can be made by stretching a string or tape across the ground in a straight line. A frame quadrat is then laid down alongside the line and the species within it recorded. It is then moved its own length along a line, and the process is repeated. Usually, more than one transect will be used in an investigation. The process gives a record of species in a continuous belt.

Measuring Abundance

Random sampling with quadrats and counting along transects are used to obtain measures of abundance. For species that don't move around, abundance can be measured in several different ways depending on the size of the species being counted and the habitat:

- Frequency - The likelihood of a particular species occurring in a quadrat. If, for example a species occurs in 15/30 quadrats, the frequency of its occurrence is 50%. This method is useful where a species is hard to count and gives a quick idea of the species present and their general distribution within an area. However, it does not provide information on the density and detailed distribution of a species.

- Percentage Cover - An estimate of the area within a quadrat that a specific plant species covers. It is useful where a species is particularly abundant or is difficult to count. The advantages in these situations are that data can be collected rapidly and individual plants do not need to be counted, but it is less useful where organisms occur in overlapping layers.

Mark-Release-Recapture

The methods of measuring abundance work very well with plant species, non-motile or very slow moving animals species that remain in one place, but not with motile organisms. These generally move away when approached, are often hidden and are therefore difficult to find and identify. Estimating the abundance of most animals therefore requires a completely different technique.

A known number of animals are caught, marked and then released back into the community. Sometime later, a given number of individuals are collected randomly and the number of marked individuals is recorded. The size of the population is then calculated using the formula in the image.

This technique relies on a number of assumptions:

- The proportion of marked to unmarked individuals in the second sample is the same as the proportion of marked to unmarked individuals in the population as a whole.

- The marked individuals released from the first sample distribute themselves evenly amongst the remainder of the population and have sufficient time to do so.

- The population has a definite boundary so that there is no immigration or emigration out of the population.

- There are few, if any, deaths and births within the population.

- The method of marking is not toxic to the individual, not does it make the individual more conspicuous and therefore more liable to predation.

- The mark or label is not lost during the investigation.

Sucession

This is the process of an environment and the species within it changing overtime in a particular area due to environmental or abiotic factors. At each stage, new species colonise the area and these may change the environment. These species may alter the environment in a way that makes it:

- Less suitable for the existing species. As a result, the new species may out-compete the existing one and so take over a given area.

- More suitable for other species with different adaptations. As a result, this species may be out-competed by the better adapted new species.

In this way, there are a series of successional changes which alter the abiotic environment. These alterations can result in a less hostile environment that makes it easier for other species to survive. As a consequence, new communities are formed and biodiversity may be changed and/or increased.

Pioneer Species and Suitable Characteristics

The first stage of this type of succession is the colonisation of an inhospitable environment by organisms called pioneer species. Pioneer species make up a pioneer community and often have features that suit them to colonisation. These may include:

- Asexual reproduction so that a single organism can rapidly multiple to build up a population.

- The production of vast quantities of wind-dispersed seeds or spores, so they can easily reach isolated situations such as volcanic islands.

- Rapid germination of seeds on arrival as they do not require a period of dormancy.

- The ability to photosynthesise, as light is normally available but other food is not. They are therefore not dependent on animal species.

- The ability to fix nitrogen from the atmosphere because, even if there is soil, it has few or no nutrients.

- Tolerance to extreme conditions.

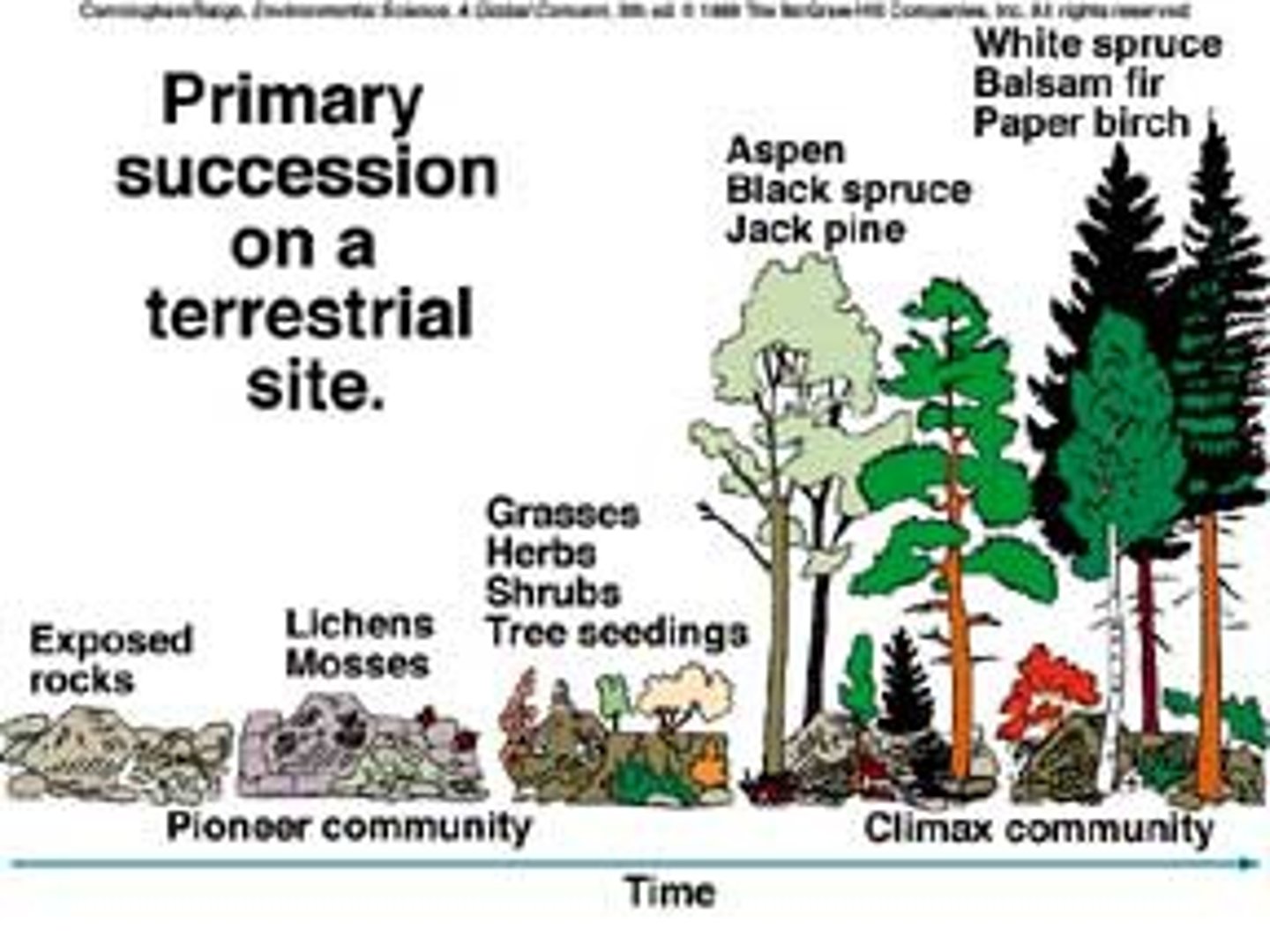

Primary Succession Example

One of the few kinds of organism capable of surviving on such an inhospitable area is lichens, and they are therefore pioneer species. In time, weathering of the base rock by the action of the lichens produces sand or soil, although this in itself cannot support other plants. However, as lichens die and decompose, they release sufficient nutrients to support a community of small plants. In this way, the lichens change the abiotic environment by creating soil and nutrients for the organisms that follow. With the continuing erosion of the rock and the increasing amount of organic matter available from dead plants, a thicker layer of soil is built up. This matter holds water and nutrients which make it easier for other plants to grow. These changes make the habitat less hostile and more suitable for the organisms that follow. Some species, such as shrubs and trees, provide more sources of food, leading to more food chains that develop into complex food webs and more stable communities. The ultimate community is most likely to be deciduous oak woodland. This stable state comprises of a balanced equilibrium of species with few, if any, new species replacing the established ones. In this state, many species flourish and there is more biodiversity. This is called the climax community which remains more or less stable over a long period of time.

Advantage of seeds germinating in fluctuating temperatures

Bare soil will fluctuate in temperature due to little to no plant cover in the area. The pioneer stage usually consists of bare soil and has to be able to survive in these conditions.

Common Features of Succession

- The abiotic environment becomes less hostile. For example, soil forms (Which helps to retain water, water retaining capacity increases) and soil depth will increase, nutrients are more plentiful, and plants provide shelter from the wind.

- A greater variety of habitats and niches (A role taken by a type of organism within its community).

- Increased biodiversity as different species occupy these habitats. This is especially evident in the early stages, peaking at mid-succession, but decreasing as the climax community is reached due to dominant species out-competing pioneer or other species, leading to their elimination from the community.

- More complex food webs, therefore meaning a more stable community.

- Increased biomass.

Climax communities are in a stable equilibrium with the prevailing climate. It is abiotic factors, such as climate, that determine the dominant species of the community. In the lowlands of the UK, the climax community is deciduous woodland, but in other climates this may be tundra for example.

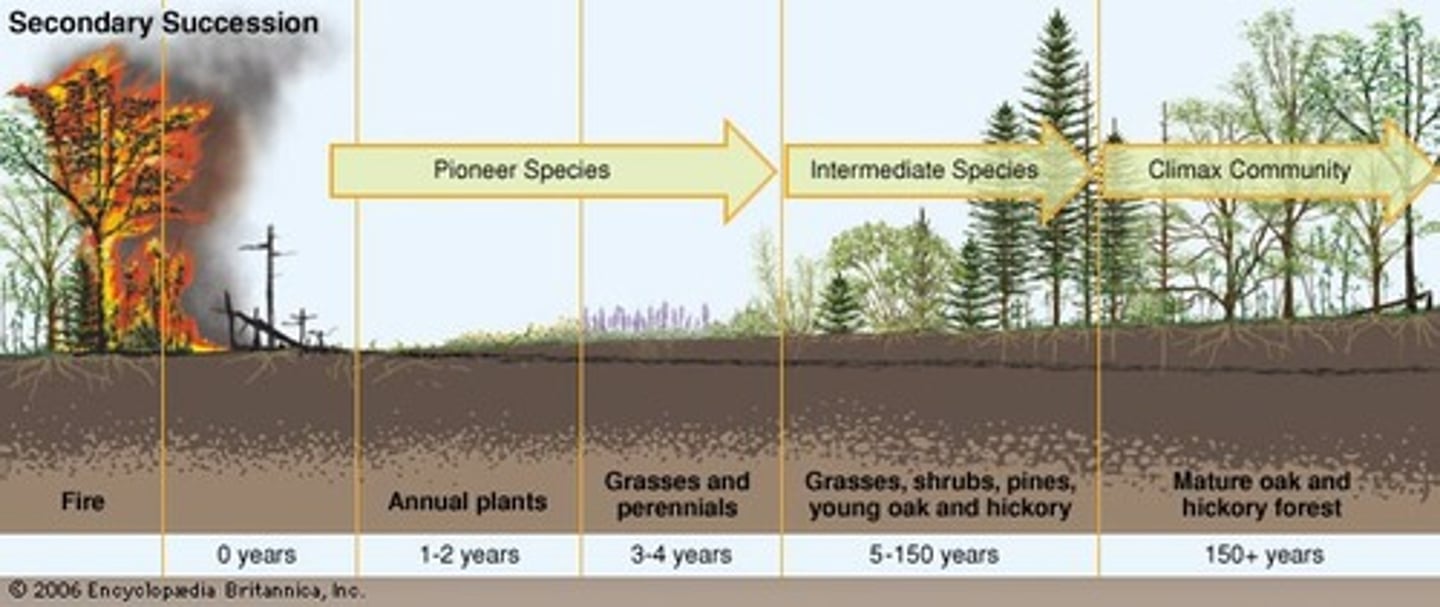

Secondary Succession

This occurs when land that has already sustained life is suddenly altered. This may be the result of land clearance for agriculture or a forest fire. The process by which the ecosystem returns to its climax community is the same as in primary succession, however it occurs more rapidly because soil already exists in which spores and seeds often remain alive, and there is an influx of animals and plants through dispersal and migration from the surrounding area. Because the land has been altered in some way, some of the species in the climax community will be different.

Comparison of Primary and Secondary Succession

Similarities:

- Results in a climax community.

- Occurs over a long period of time.

- Shrubs and small trees grow.

Differences:

- There is no previous life in primary succession and so occurs in an area that was previously inhabitable, while soil is already present in secondary succession and thus occurs in areas where organisms lived previously.

- Primary succession would occur after lava cools after a volcano eruption for example, while secondary succession would occur after a forest fire for example.

- Soil must be formed before plants can grow in primary succession, and so it starts from rocks, while grasses are the first plants to grow in secondary succession.

What is meant by conservation?

This is the management of the Earth's natural resources by humans in such a way that maximum use of them can be made in the future. This involves active intervention by humans to maintain ecosystems and biodiversity.

Main Reasons for Conservation

- Personal - To maintain our planet and therefore our life support system.

- Ethical - Other species have occupied the Earth far longer than we have and should be allowed to coexist with us. Respect for living things is preferable to disregard for them.

- Economic - Living organisms contain a gigantic pool of genes with the capacity to make millions of substances, many of which may prove valuable in the future. Long-term productivity is greater if ecosystems are maintained in their natural balanced state.

- Cultural and Aesthetic - Habitats and organisms enrich our lives. Their variety adds interest to everyday life and inspires writers, poets etc who entertain and fulfil us.

Conserving Habitats by Management of Succession

Any climax community has undergone a series of successional changes to reach its current state. Many of the species that existed in the earlier stages are no longer present as part of the climax community because their habitats have disappeared as a result of succession, species have been out-competed by other species, or they have been taken over for human activities. One way of conserving these habitats, and hence the species they contain, is by managing succession in a way that prevents this change to the next stage.

If a factor that is preventing further succession is removed, the ecosystem develops naturally into its climatic climax (Secondary succession). For example, sand dunes can be managed to prevent succession to woodland leaving wet areas where species like natterjack toads can thrive.

In-Situ Conservation

This s considered the most appropriate way of conserving biodiversity and is where the areas where the populations of species exist naturally are conserved. Protected areas form a central element of any national strategy to conserve biodiversity. Examples include national parks, wildlife sanctuaries and biosphere reserves.

In-depth example - Banff National Park contains a wide variety of species and is bisected by a large commercial road called the Trans-Canada Highway. To reduce the effects of the four-lane TCH, 23 wildlife crossings were built to ensure habitat connectivity and to protect motorists. In 1996, Parks Canada developed a contract with university researchers to assess the effectiveness of the crossing. Using a variety of techniques to monitor the crossings over the last 25 years, scientists report that 10 species of mammals, including deer, elk, moose etc, have used the 24 crossings a total of 84,000 times as of January 2007. The research also identified a learning curve such that animals need time to acclimate to the structures before they feel comfortable using them. Clevenger et al reported that the use of wildlife crossings and fencing reduced traffic-induced mortality of large ungulates (Hoofed mammals) on the TCH by more than 80%.

Ex-Situ Conservation

This is the preservation of components of biological diversity outside their natural habitats. This involves conservation of genetic resources, as well as wild and cultivated or species, and draws on a diverse body of techniques and facilities.

Captive Breeding

This is the process of maintaining plants or animals in controlled environments. This is sometimes employed to help species that are being threatened by human activities such as habitat loss, fragmentation, over hunting or fishing, pollution, predation, disease and parasitism.

Describe how the investigators could obtain the value for vegetation cover in each quadrat.

Subdivide the quadrat into many squares and count the squares whose cover is around 50% or more.

Give the conditions necessary for the results from mark-recapture-release investigations to be valid.

- No immigration/migration.

- No reproduction.

- Marking does not influence behaviour of the woodlice/increase their vulnerability to predation.

- The sample/population is large enough.

Suggest how sympatric speciation may have occurred between two species.

The original population would have resided in one area, and within this population there will be genetic variability between all of the organisms within it. At a particular point, a section of the population will have become reproductively isolated from the main population, and the two populations will now reside in slightly different habitats with different abiotic conditions. Then as time moves on, the gene pools of the two populations will become incresaingly different and it will reach the point where there will no longer be successful interbreeding between the two populations to produce fertile offspring.

Suggest advantages of using island populations

All individuals can be recorded on small islands and so there will be no sampling error, inbreeding with close relatives is more likely, and there will be little gene flow in and out of the population.

How many antigen-determining alleles will be present in a white blood cell? Give a reason for your answer.

Two as white blood cells are diploid cells so alleles are present on each chromosome of a homologous pair.

Explain what is meant by co-dominant alleles.

Both alelles are equally dominant and thus both alleles are expressed in the phenotype.

A recessive allele which has harmful effects is able to reach a higher frequency in a population than a harmful dominant allele. Explain how.

Recessive alleles can be carried by individuals without being expressed in their phenotype, and so the organisms that are carries are more likely to reproduce while the affected are less likely to reproduce, and so recessive alleles are more likely to be passed on.

Suggest why a genetic disorder can be more common in males.

Males only have one X chromosome, and so if they have the recessive allele, there will be no corresponding allele on the Y chromosome to mask its effect, and so a single copy of the recessive allele will be expressed.

What is meant by a recessive allele?

An allele which is only expressed in the homozygote.

Snowy tigers inhabit the same grasslands as orange, striped tigers. These grasslands are dominated by very tall grass plants. Snowy tigers are less successful hunters. Suggest why.

The white colour will stand out amongst the tall grass plants, and so the prey of the snowy tiger will be aware of their presence sooner.

Explain how observation of the chromosomes from an embryo cell could enable the sex to be determined.

The sex chromosomes of females will be XX while the sex chromosomes of males will be XY. To distinguish between the two types, it must be noted that the Y chromosome will be much shorter than the X chromosome.

Why is it important to use the same type of plant in an experiment?

A different type of plant will act as a confounding variable on the results due to genetic dissimilarity, and so by ensuring that the same plant is used, the different conditions will have plants which are genetically similar.

Explain directional selection in terms of genetics and where a desired characteristic is selected.

The desired characteristic is selected and selectively bred with another organism with the desired characteristic so these organisms will pass on their alleles to the next generation, thus meaning that the frequency of the alleles for production of the desired characteristic will increase.

Explain the results of a general genetic cross involving a linked allele.

The variants with the smaller number of offspring produced would not normally occur as the genes are linked to a specific allele, but the process of crossing over allows them to occur, so fewer numbers of these recombinants will be produced in comparison to the normally expected combinations

In genetic crosses, the observed phenotypic ratios obtained in the offspring are often not the same as the expected ratios. Suggest reasons why.

- Small sample size.

- Fertilisation of gametes is random.

- Linked genes.

- Epistasis.

Why will the number of people showing a particular characteristic rapidly increase?

The allele will be dominant and thus will always be expressed when present in the offspring and will be expressed when only one copy is present.

Lactase persistence is caused by a mutation in DNA. This mutation does not occur in the gene coding for lactase. Suggest and explain how this mutation causes LP.

A mutation may occur in the promoter region for either the gene or transcription factor, or mutation in the gene for the transcription factor, and this will cause the lactase gene to be continuously transcribed.

Inheritance of Mitochondrial DNA

In humans, mitochondrial DNA is inherited from the mother because an egg cell has many more mitochondria than a sperm cell.

The ecologist calculated the total prey index for each of the places that had been studied. In order to do this, he gave each prey species a value based on how much food was available to wolves from the prey animal concerned. He called this value the prey index.

The ecologist considered that the prey index gave a better idea of the food available than the prey biomass in kg. Suggest why the prey index gives a better idea of food available.

Wolves do not eat all of the prey animal, meaning they will generally avoid large bones, and these inedible parts will make up different proportions on each organism.

Explain how changes in the numbers of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria can demonstrate the process of succession.

When oxygen concentration lowers, there will be a higher number of anaerobic bacteria and less aerobic bacteria, so the anaerobic bacteria will not have to compete with them, and thus in these conditions, the aerobic bacteria will not be able to survive.

Explain the features of an ecological succession.

At the initial stage, there will be colonisation from a pioneer species which has the ability to survive in a hostile environment. These small organisms will eventually die, leading to an increase in organic matter in the environment and thus a change in the abiotic environment, and so species will colonise once there is a stage. This will thus lead to an increase in species diversity and a stable community or organisms.

Explain how deforestation might affect the process of succession in a lake.

The removal of forest cover may result in soil erosion or leaching which may provide additional minerals to allow the organisms residing in the environment to continue to grow.

Explain five factors that can limit the size of populations in a climax community.

- The availability of nutrients such as nitrate which are necessary for the growth of plants.

- The number of producers providing energy for a food chain, affected by light intensity which in turn affects the rate of photosynthesis.

- Predation may occur or a disease may kill certain members of a specific.

- Space for nest building and the development of niches.

- Inter-specific competition may occur over availability of prey, water etc.

How might diversity increase along a transect?

- There may be a greater variety of food sources.

- There may be more habitats and niches within the community.

A student used the mark-release-recapture technique to estimate the size of the population of sand lizards. She collected 17 lizards and marked them before releasing them back into the same area. Later, she collected 20 lizards, 10 of which were marked. Calculate the number of sand lizards in this area.

(17*20)/10 = 34 lizards.

Succession occurs in natural ecosystems. Describe and explain how succession occurs.

Succession begins with the colonisation of a pioneer species which, after death, will be decomposed and have their organic matter incorporated into the soil in the environment. This will lead to a change in the abiotic environment of the area, thus making the conditions within it less hostile, and this will lead to the colonisation of new plants into the area as they will be able to survive in these new conditions. This will lead to a change in the biodiversity of the area, and overtime, the stability of the community will reach its peak when there is no new introduction of species into the area, meaning the climax community of the area has been reached.

Changes in ecosystems can lead to speciation. In Southern California 10 000 years ago a number of interconnecting lakes contained a single species of pupfish. Increasing temperatures caused evaporation and the formation of separate, smaller lakes and streams. This led to the formation of a number of different species of pupfish. Explain how these different species evolved

The different species of pupfish have become geographically isolated from each other due to the formation of the separate lakes, each of which have different abiotic conditions. There will be variation within each of these populations of pupfish due to mutations, and this will lead to selection occurring whereby those pupfish with advantageous alleles to their environment will be more likely to survive and pass on their alleles to the next generation, and those will less advantageous alleles will likely have less reproductive success, so there will be a lower likelihood that they will survive and pass on their alleles. This will therefore lead to a change in the allele frequency within the population, and the species of pupfish will become so genetically different to each other that they will be unable to successfully interbreed with each other.

Describe how you would investigate the distribution of marram grass from one side of a sand dune to the other.

A transect should be laid out stretching across from one side of the sand dune to the other, and then the percentage cover of marram grass should be measured at regular intervals along the transect using a frame quadrat.

Marram grass is a pioneer species that grows on sand dunes. It has long roots and a vertically growing stem that grows up through the sand. Sand dunes are easily damaged by visitors and are blown by the wind. Planting marram grass is useful in helping sand dune ecosystems to recover from damage.

Use your knowledge of succession to explain how.

The marram grass will stop the sand from shifting and will improve the content of the soil to make conditions within the ecosystem less hostile such as by adding nutrients or improving the water retention of the area.