Eating Disorders

1/67

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

68 Terms

what are eating disorders?

a form of mental disorder characterized by problems with eating

as a group, eating disorders distinguished from normal variations in eating bas4ed on at least 1 of the following

present distress

disability/impairment

eating disorders in the DSM-5

anorexia nervosa (AN)

bulimia nervosa (BN)

binge eating disorder (BED)

other specified feeding or eating disorder (OSFED)

atypical AN

sub threshold BN

sub threshold BED

purging disorder (PD)

night eating syndrome (NES)

anorexia nervosa (AN)

Restriction of energy intake leading to significantly low body weight

DSM-5 lets clinician determine what is low weight for an individual

intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, or persistent behavior that interferes with weight gain

disturbance in experience of body weight, undue influence of weight/shape on self-evaluation, or denial of the seriousness of low weight

AN Subtypes (restricting and binge/purge)

both meet same criteria 1-3

bulimia nervosa (BN)

Recurrent episodes (occurring at least 1/wk on average for 3 months) of binge eating characterized by both

eating within a 2-hour period an amount of food that is definitely larger than most people would eat in a similar condition

a sense of loss of control during the episode

Recurrent (occurring at least 1/wk on average for 3 months) inappropriate compensatory behaviors to prevent weight gain

undue influence of weight and shape on self-evaluation

No low weight (e.g., not anorexia nervosa)

Binge Eating Disorder (BED)

Recurrent (occurring at least 1/wk on average for 3 months) episodes of binge eating (same core features as in BN required)

Binge episode accompanied by ≥3 associated symptoms:

eating much more rapidly than normal

eating until feeling uncomfortably full

eating alone because of feeling embarrassed by how much one is eating

feeling disgusted with oneself, depressed, or very guilty afterwards

Distress regarding binge eating is present

not low weight and no compensatory behaviors

i.e., it’s not AN or BN

problems with DSM-5 categories

many people with clinically significant disorders of eating do not meet DSM-5 criteria for AN, BN, or BED, and the boundaries between them are not always clear

OSFED

Disorder of eating that does not meet criteria for AN, BN, or BED or the feeding disorders (pica, rumination, ARFID)

Atypical AN - all criteria for AN except that, despite significant weight loss, the individual’s current weight is in the normal range

All criteria for BN were met except that binge eating and ICB occur at a frequency of less than once/week or duration of less than 3 months

All criteria for BED are met except that binge eating occurs at a frequency of less than once/week or duration of less than 3 months

Purging Disorder (PD) - recurrent purging in the absence of binge eating

vomiting, laxatives, diuretics

Night Eating Syndrome (NES) - recurrent night eating (nocturnal eating or excessive intake after evening meal) of which the person is aware

Diagnostic and Statitical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)

produced by the American Psychiatric Association

contents have changed across each of its 5 editions

International Classification of Diseases (ICD)

produced by the World Health Organization

contents have changed across each of its 11 editions

How is the ICD-11 different from the DSM-5?

ICD-11 doesn’t have “specified” disorders in the Other Specified category

Different definition of binge eating:

“A binge eating episode is a distinct period of time during which the individual experiences a subjective loss of control over eating, eating notably more or differently than usual, and feels unable to stop eating or limit the type of amount of food eaten.”

BED does not require “associated characteristics”

DSM-5 categories

many people with clinically significant disorders of eating do not meet DSM-5 criteria for AN, BN, or BED, and the boundaries between them are not always clear

feeding disorders in the DSM-5

pica, rumination disorder, avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID)

pica

persistent eating of non-nutritive substances for a period of at least one month

the eating of non-nutritive substances is inappropriate to the developmental level of the individual

the eating behavior is not part of a culturally supported or socially normative practice

if occuring in the presence of another mental disorder (e.g., autism spectrum disorder), or during a medical condition (e.g., pregnancy), it is severe enough to warrant independent clinical attention

Pica Treatment

test for nutritional deficiencies

Calcium and iron deficiencies most common

treat any deficiencies with diet supplements

behavioral interventions

Reinforce (reward) discarding a non-food item

Rumination Disorder

repeated regurgitation of food for a period of at least one month. Regurgitated food may be re-chewed, re-swallowed, or spit out

the repeated regurgitation is not due to a medical condition (e.g., gastroesophageal reflux)

the behavior does not occur exclusively during AN, BN, BED, or ARFID

if occurring in the presence of another mental disorder (e.g., intellectual developmental disorder), it is severe enough to warrant independent clinical attention

rumination disorder treatment

behavioral training

train patients to identify when regurgitation is about to occur

move from subconscious to conscious behavior

engage in diaphragmatic breathing at first sign of regurgitation

relax muscles and prevent food from coming up

Avoidant-Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID)

An eating or feeding disturbance as manifested by persistent failure to meet appropriate nutritional and/or energy needs associated with one (or more) of the following:

significant loss of weight (or failure to achieve expected weight gain or faltering growth in children)

significant nutritional deficiency

dependence on enteral feeding or oral nutritional supplements

marked interference with psychosocial function

The behavior is not better explained by a lack of available food or by an associated culturally sanctioned practice

The behavior does not occur exclusively during AN or BN, and there is no evidence of a disturbance in the way one’s body weight or shape is experienced

if occuring in the presence of another condition/disorder, it is severe enough to warrant independent clinical attention

(sensory factors, fear of consequences, lack of interest)

ARFID treatment

family-based treatment

also a treatment for AN in children, blurring distinctions between ARFID and AN

cognitive behavioral treatment

Differences between Eating and Feeding Disorders

Eating Disorders are characterized by body image disturbance (AN and BN) or distress (BED) that is absent in Feeding Disorders

Feeding disorders are diagnosed based on the presence of behaviors and the absence of ED-related cognitions because they typically emerge at ages where abstract concepts do not exist

Feeding disorders typically emerge when parents are feeding children rather than children being responsible for feeding themselves (a.k.a., eating)

BMI of obese adults

BMI > 30 kg/m²

>40 kg/m2 is morbid

Waist circumference

>40’” in men or >35” women

obese BMI for ages 2-19 years

>95th percentile for age and gender

Why has obesity increased?

changes in diet (1974→2014)

where we eat

what we eat

when we eat

how we eat

why we eat (marketing)

changes in activity level

Is obesity an eating disorder?

Imbalance between energy needs and energy intake suggests that obesity represents a problem with eating too much

linked to BED

however, an ED characterized by excessive food intake already exists (BED), and not everyone with BED is obese

Most individuals who are obese do not have BED or any loss of control over their eating

According to AMA and WHO, obesity is a disease

Death Risk BMI (Obesity)

BMI 25-30: lowest risk of death from any cause

BMI > 35 increased risk

BMI < 18.5 increased risk

Who is stereotyped to have an eating disorder?

women

Grillot & Keel, 2018 (Treatment Seeking for Eating Disorders)

Background

Most individuals with an eating disorder never seek treatment for their problem, and this is particularly true for men with eating disorders

In addition, most people w/ eating disorders don’t recognize that they have a problem with their eating

Why are men even less likely to seek treatment than women?

Self-recognition of an ED is required to seek treatment

Based on stereotypes that eating disorders are a “female” disorder, men are less likely than women to recognize when they have an eating disorder

Treatment Seeking for Eating Disorders (Grillot & Keel, 2018)

Methods

Secondary analyses of survey data collected in 2012 from 2,514 respondents

Information collected

Gender, DSM-5 criteria for an ED taken from the Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale

“questions”

Height and weight

checklist of past mental disorders

Discussion

Most people with an ED don’t recognize it and never get treatment

men are less likely to seek treatment

not recognizing an ED is barrier to treatment seeking for both men and women

women and men are equally bad at recognizing that they have an eating disorder

more research is needed to understand other barriers that are unique to men

What protects men from EDs?

AN and BN are defined by body image disturbance related to weight and shape

intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat

misperception of the body as being too fat

undue influence of weight/shape on self-evaluation

BED not defined by body image disturbance

See less (almost half) gender ratio seen for AN and BN

“Reverse Anorexia,” “Bigorexia,” “Muscle Dysmorphia”

Dietary manipulations to increase muscle mass/decrease body fat

excessive exercise to build muscle mass

misperception of size: perceive body as puny despite a well-muscled physique

abuse of anabolic-androgenic steroids

Anabolic-Androgenic Steroids

Man-made derivatives of testosterone

increase protein synthesis and muscle mass

reasons for abuse: desire for increased strength, improved athletic performance, enhanced appearance

negative effects

damage to musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, endocrine/reproductive, and liver systems

increased mood lability, anger, and physical outbursts

Stereotype vs. reality

Eating disorders are less common in men than in women

in addition, men may be more likely to suffer from conditions that have been labeled “body dysmorphic disorders” than “eating disorders”

however, men comprise a larger portion of those suffering from eating disorders than those included in ED treatment and research

Gordon, Perez, and Joiner (2002)

Does race/ethnicity influence recognition of an ED?

Procedure: Read a 5-day diary depicting a high school girl’s activities and then complete series of questions about girl

IV: Mary’s ethnicity (white vs black/hispanic)

DV: Does Mary have any notable problems? How would she respond to _____ [questions from eating disorder scale]

Results:

identification of eating problem linked to Mary’s ethnicity

responses to EDI drive for thinness items did not differ between conditions

suggests a disconnect between the ability to recognize disordered attitudes/behaviors and label this as an “eating problem” in a person who does not fitthe stereotype

results not influenced by participants’ ethnicity

Ethnicity & Access to Care (Becker et al., 2003)

Does race/ethnicity influence access to care?

Study 1: Compared to White participants, both Latino (.60) and Native American participants (.51) were significantly less liekly to recieve referral for treatment controlling for symptom severity

Study 2: No significant difference among racial/ethnic groups in likelihood to seek treatment. Ethnic minority participants were less likely to be asked about eating by doctors and less likely to receive treatment referral (31%) compared to White participants (60%)

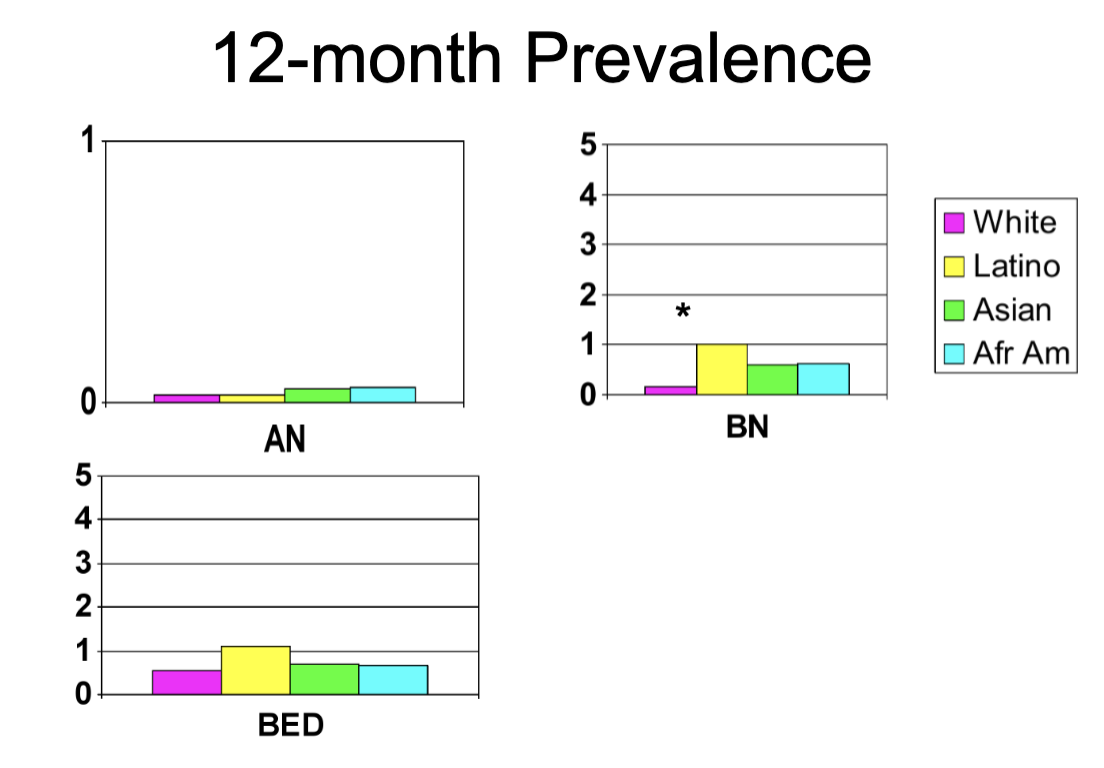

Comparison of ED Prevalence (Marques et al., 2010)

Do racial/ethic groups differ in ED Prevalence?

Pooled Data from the NIMH Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiological Studies (CPES)

Is acculturation to dominant culture linked to ED risk?

Significant positive association between acculturation and ED prevalence in Latino participants

No significant association between acculturation and ED prevalence in Asian participants

Is the likelihood of mental health care associated with race/ethnicity for those with EDs?

White participants with ED significantly more likely to have received mental health treatment compared to Latino, Asian, and African American participants

ED & culture

eating disorders are more common in industrial, often Western, cultures

eating disorders appear to be a modern problem

increaser in eating disorder incidence associated with increasing idealization of thinness

Non-western cultures (AN and BED prevalent in all 5). Where is BN prevalent in non-Western cultures?

East Asia, Middle Eastern/Arab, Southeast Asia

Introduction of TV to Ethnic Fijians (Becker et al., 2002)

Does exposure to Western media increase disordered eating in non-Western cultures?

Fiji has a low prevalence of eating disorders; values idealize a fuller figure, encourage robust appetites, and view thinness as arising from a lack of family support/caring

83% of girls in 1998 reported that TV influenced their or their friends’ feelings and behaviors about body weight/shape

77% indicated that TV influenced their own body image

40% believed that losing weight/eating less would help them obtain successful careers

associated with significant increase in EAT-26 scores and vomiting behavior

Native Korean vs Korean immigrant vs Korean American ED levels

NK and KI have higher disordered eating levels than KA

suggests that Western culture is not the only source of cultural influences that may contribute to eating disorders

Non-Western cultures contribute to EDS

no association between acculturation to Western ideals and eating pathology for Asian individuals in the US or outside the US

AN is not culturally bound illness

Korean women in Korea have higher EAT-26 scores than Korean women in the US

AN: 13th to 16th Centuries: “Anorexia Miribalis”

Holy Anorexia

Self-starvation as penitence, path to religious piety and purity

Saint Hedwig

Saint Catherine of Siena

Church became concerned

AN: 16th to 18th Centuries: “Miraculous Maids”

Exhibition of starving abilities

Claim to subsist soley on air or water, small amounts of food

Mixture of spiritual and mystic beliefs

Interest by physicians, deaths reported

1689: Sir RIchard Morton (described 2 patients with AN)

AN: 18th to 19th Centuries: Case Studies

1770s: Timothy Dwight

1860: Luis Victor Marce

(Gull, 1888): Miss K. R——

BN: 20th Century

1903: Janet

First to describe a patient with bulimic behaviors: compulsive secretive binges and vomiting

1932: Wulff

described patients with periods of intense cravings and overeating, followed by vomiting

1958: Binswanger

After being teased for weight, patient began using thyroid pills, laxatives, and comiting; consumed dozens of oranges and pounds of tomatoes

Who published the first clinical paper on bulimia nervosa

1979: Gerald Ressel

“An ominous variant of anorexia nervosa”

Individuals with a morbid fear of becoming fat who overeat and purge afterwards

BED: Long Road to Diagnosis

1959: Albert Stunkard

Clinical observation of recurrent episodes of binge eating in some individuals with obesity

Large amounts of food at irregular intervals

1992: “Binge eating disorder” was introduced at the International Conference on Eating Disorders as a provisional diagnosis

2003: Cooper and Fairburn

Noted needed for attention and diagnostic clarity regarding BED

Difficulty distinguishing BED from other forms of overeating (e.g., obesity, non-purging bulimia nervosa)

Have eating disorders become more common with increased idealization of thinness?

Prevalence: proportion (%) of population with illness

Incidence: number of new case per a set number of persons per year (e.g., per 100,000 persons/year)

Prevalence vs. Incidence

Prevalence influenced by new illness onset and illness chronicity

Incidence only reflects new illness onset

Summary of AN over time

Cases found in non-Western cultures in the absence of Western influence

Cases found long before the introduction of AN to psychiatric nomenclature

Only a modest increase in AN incidence during a period of dramatically increasing idealization of thinness

Summary of BN over time

no cases foudn in the absence of Western influence

few cases found before introduction of BN to psychiatric nomenclature, and historical cases differ in demographic and clinical features

dramatic increase in BN incidence accompanying increasing idealization of thinness over second half of 20th century

Summary of Eating Disorders over time

AN has demonstrated modest significant increase over time, but existed long before emergence of the thin ideal

BN demonstrated a dramatic significant increase in latter half of 20th century that appeared to be receding heading into the new millennium

combined with information on culture and ethnicity - more evidence that BN influenced by sociohistorical factors than AN

Too little data on BED, PD, or NES to draw conclusions

Scientific Method

Step 1: Frame a research question

Step 2: Conduct a literature review

Step 3: Form a hypothesis

Step 4: Design a study

Step 5: Conduct the study

Step 6: Analyze the data

Step 7: Report the results

Methods in Eating Disorders Research

Ethnical constraints contribute to various indirect approaches for understanding causes

Cross-sectional/correlation studies

Longitudinal Studies

Retrospective Follow-back

Prospective Follow-up

Experimental Studies

Analogue designs

Treatment/Prevention designs

Designing a Cross-sectional Design

measure all variables at the same time and see how they are associated

pros

requires least resources

time

money

if hypothesis NOT supported in cross-sectional design, saves resources for future hypotheses

Cons

depending on variables, limited inferences regarding cause and effect, “correlation does not prove causation”

variable C could be an underlying third variable

Designing a Longitudinal Study

measure variables over time to see how one variable predicts the other variab;es

pros

for A to casue B, A must precede B in time

allows identification of whether A increase risk for a B (“risk factor”)

Cons

resource-intensive

in prospective follow-up longitudinal designs, Variable A has to be measured before onset of Variable B

for eating disorders, this is a fairly young age

if variable B has low base rate (i.e., low prevalence), one may not observe adequate change in Variable B to reliably determine the association between Variable A and Variable B (i.e., statistical significance)

Additional limitation

cannot draw causal inferences; it’s really just a correlation over time

Retrospective Follow-back design (longitudinal)

compare individuals with an ED tot hose without on factors present BEFORE the age of ED onset

Pro: adequate number of cases

Con: retrospective recall bias

Prospective Follow-up design

start with sample without ED, measure factors, and then follow participants to see which factors predict ED onset

pro - no recall bias

con - few cases, so use broad measures

Designing Experimental Designs

Experimentally manipulate A to see what effect that has on B

Pros

Allows for strongest inferences regarding causation

cons

cannot ethically test hypotheses regarding causes of eating disorders

anologue studies

treatment prevention studies

analogue studies (experimental)

analogue refers to analogy

dieting is like self-starvation

overeating is like binge eating

discrepancy between current and ideal body figure is like body image disturbance

very focused DV

experimental manipulation of very focused independent variable (IV)

does manipulation of IV cause change in DV

Pros and Cons of analogue studies

Pros

many require only slightly more resources than used in cross-sectional designs

strong causal inferences possible

Cons

Causal inferences limited to specific variables examined

Questionable ecological validity

Intervention Studies

Two types

Treatment

Prevention

IV is your assigned condition

Treatment study - SSRI vs. Placebo

Prevention study - Cognitive Dissonance (CD) vs Healthy Weight Control (HWC)

DV is eating disorder/disordered eating

Intervention Studies: Treatment

if outcome is superior in SSRI condition compared to placebo condition, then SSRI caused improvement

Pro - with large samples, adequate power to see change

Con - factors that contribute to remission not necessarily part of cause

Intervention Studies: Prevention

If outcome is superior in CD condition compared to HWC, then CD prevented ED onset

Pro - most powerful design for demonstrating causal factors

Con - resource intensive given low base rate of ED

Analyzing Data

Descriptive statistics

Inferential statistics

Inferential statistics

Tests of Association (e.g., is dieting frequency associated with binge eating frequency?)

Ex., correlation, regression (linear vs. logistic)

Tests of Differences (e.g., do dieters binge more frequently than non-dieters?)

Ex., t-tests, ANOVA

Risk and Maintenance Factors (Dakanalis et al. 2017)

Question: Do appearance-ideal internalization, body dissatisfaction, dieting, negative affect, and self-objectification contribute to?

risk for onset of an eating disorder?

maintenance of an eating disorder?

Analyses: descriptive analyses

who has an ED at each time point

IV = apperance ideal internalization, body dissatisfaction, dieting, negative affect, self objectification

DV = group

Prediction of ED onset using logistic regression

Prediction of ED maintenance using logistic regression

Results:

The 4 groups differed on all 5 factors

Baseline levels of each factor, and change in each factor predicted onset of ED

Baseline levels of each factor, and change in each factor predicted maintenance of ED

Visual comparison of contributions of each factor suggested that self-objectification might have the greatest impact on both onset and maintenance of ED

Discussion:

Overlap in factors contributing to onset and maintenance suggest that prevention and treatment efforts can focus on same set of factors

Self-objectification deserves greater attention in risk and maintenance models

may influence the link between other factors and EDs in onset and maintenance

How thin is too thin (AN)?

General guideline for adults: less than 85% of weight based on age/height

BMI ≤ 18.5