Ancient Art and Architecture: Minoan to Roman Empire

1/74

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

75 Terms

Figure of a Woman (Cyclatic)

Palace of Knossos (Minoan)

Marine Style Octopus Jar (Minoan)

Snake Goddess Figurines (Minoan)

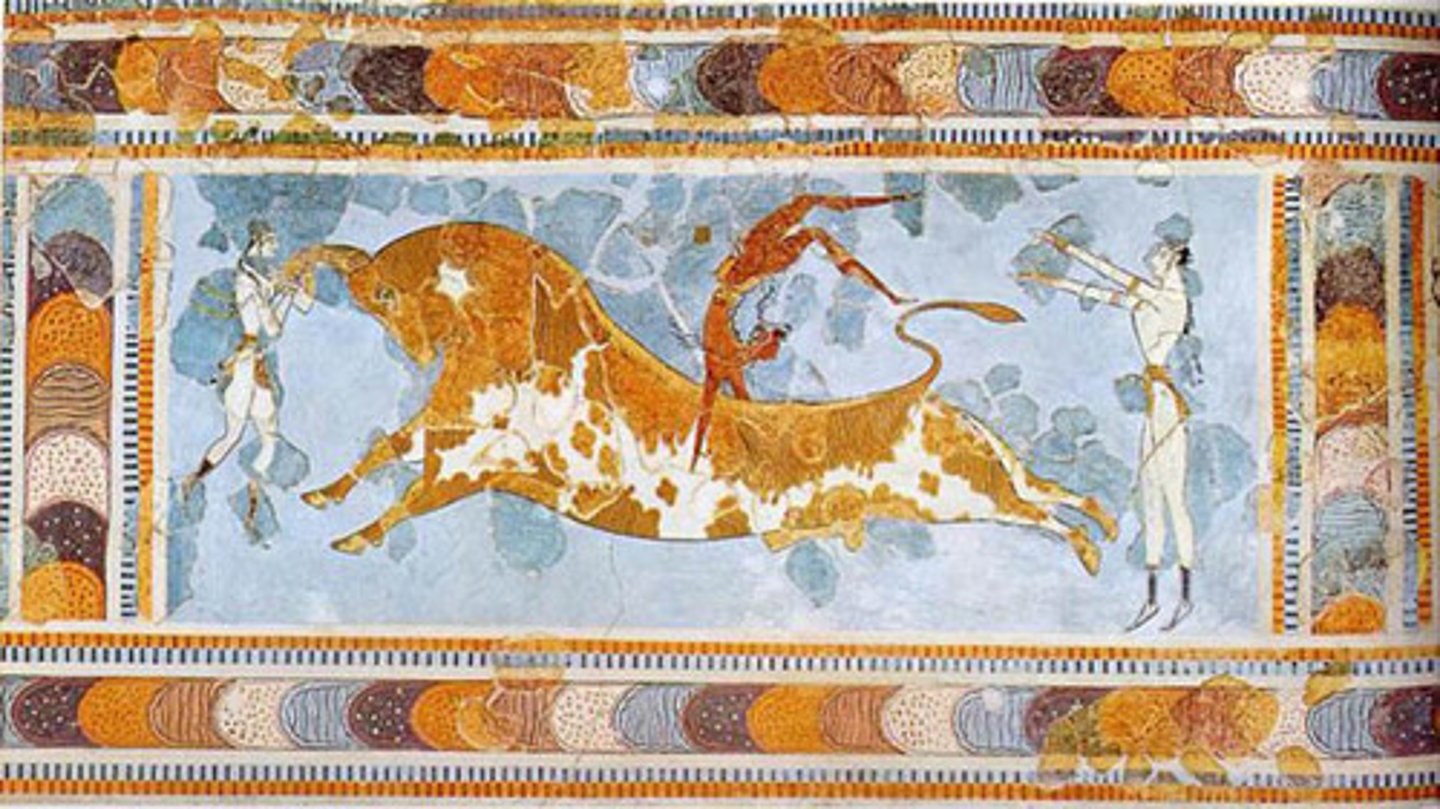

Bull-Leaping Fresco, Palace of Knossos (Minoan)

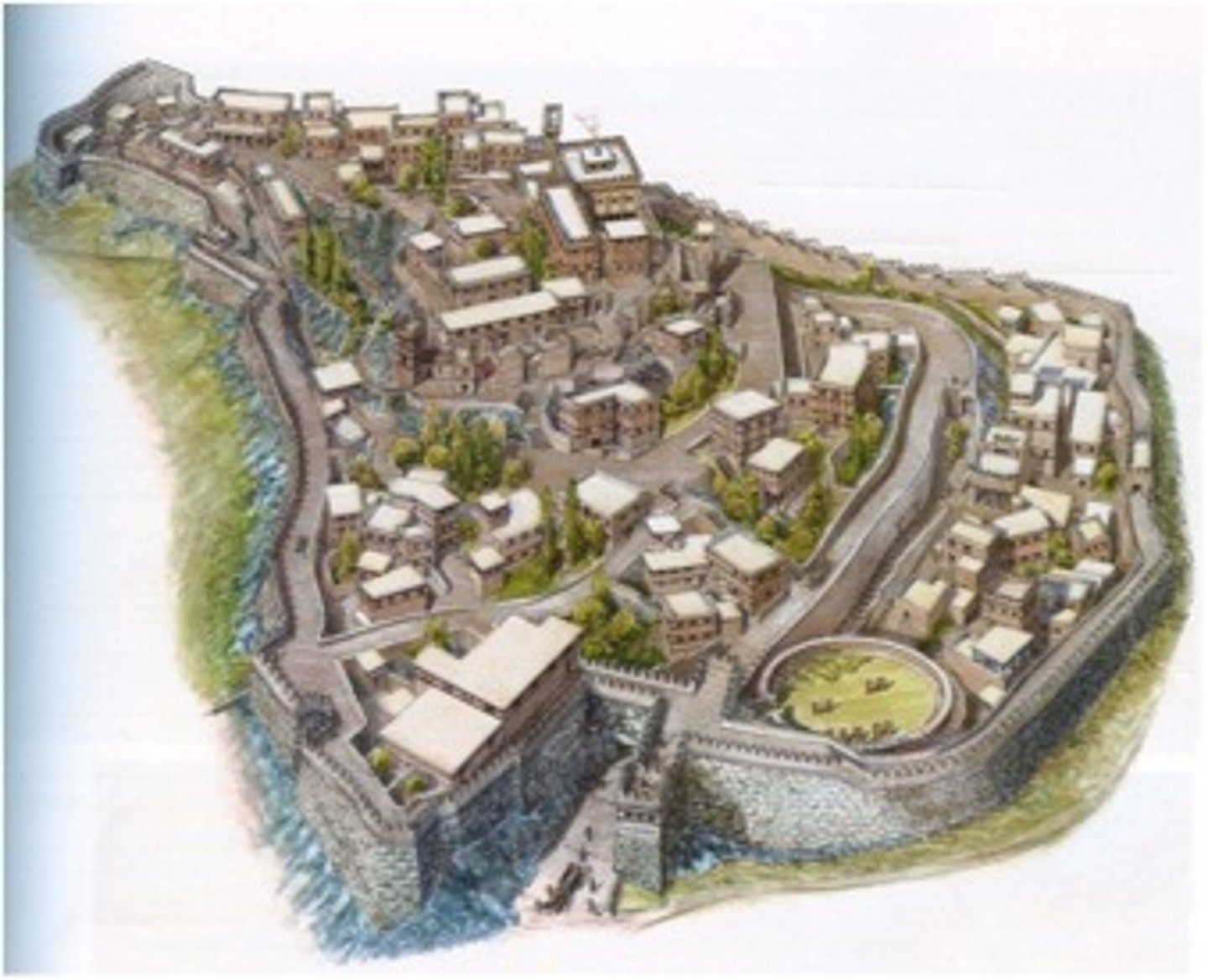

Citadel at Mycenae (Mycenean)

Lions Gate at Mycenae (Mycenean)

Dipylon Krater (Geometric/Orientalizing)

Mantiklos Apollo (Geometric/Orientalizing)

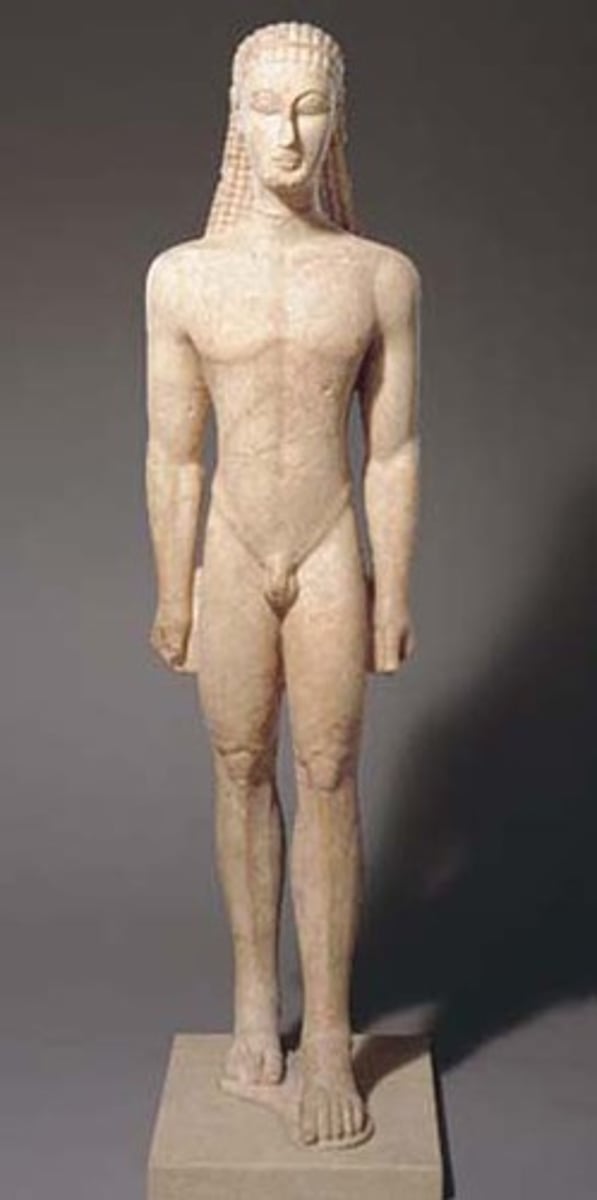

Metropolitan Korous (Archaic)

Peplos Kore (Archaic)

Temple of Hera (Archaic)

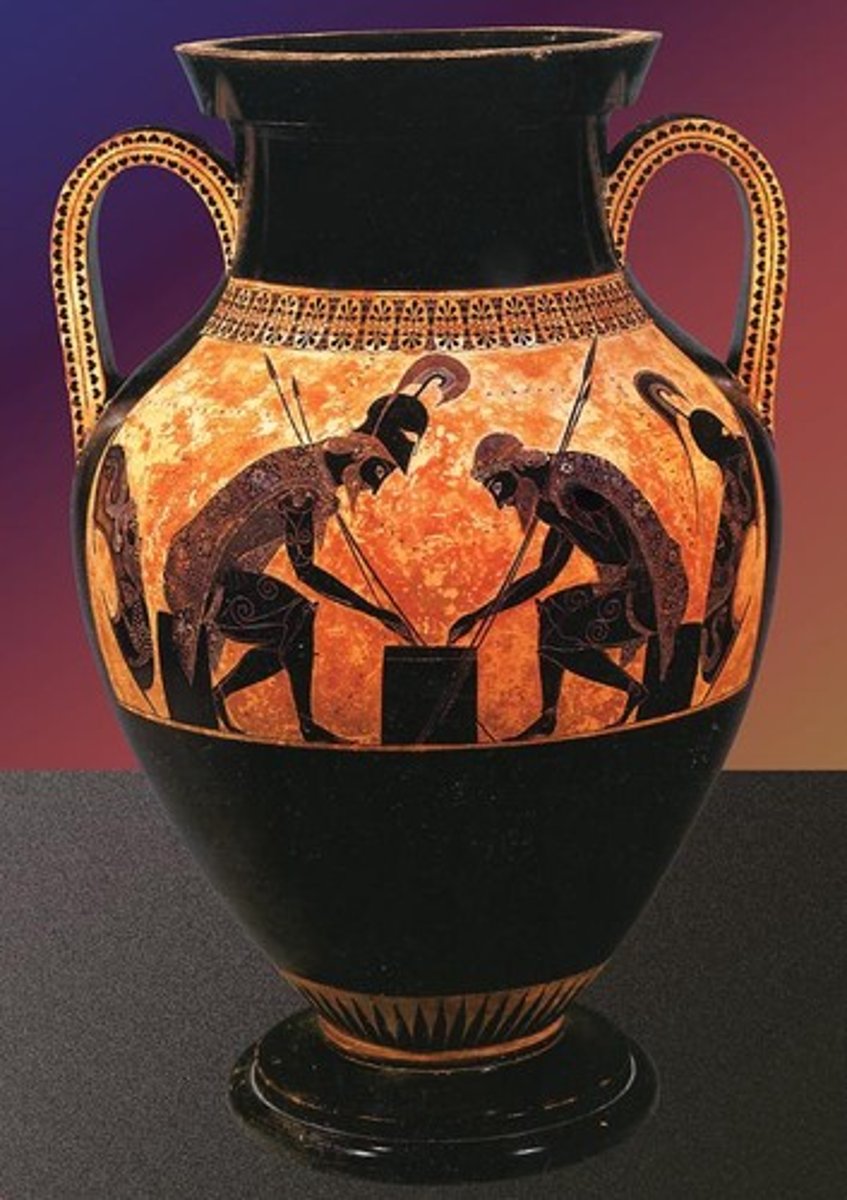

Exekias, Achilles and Ajax Playing a Dice Game (Archaic)

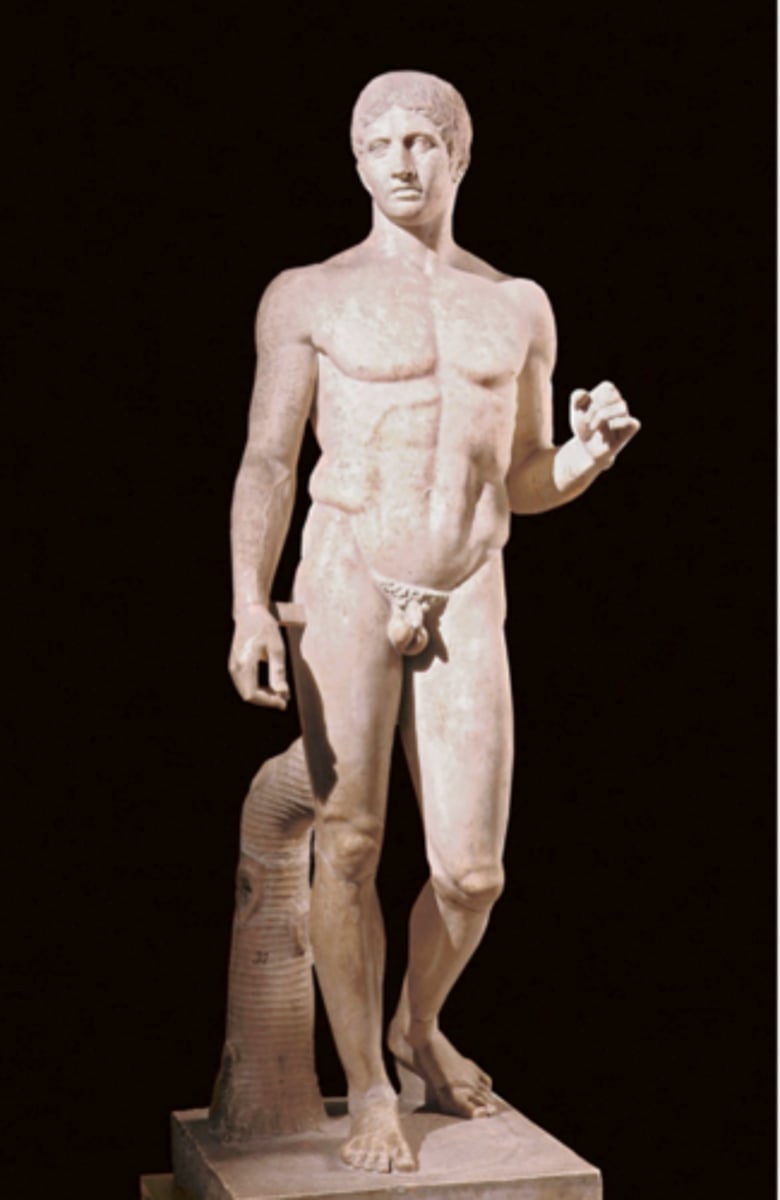

Polykleitos, Doryphoros (Spear Bearer) (Classical)

Warrior from Riace (Classical)

Athenian Acropolis (Classical)

Iktinos, Parthenon, Athenian Acropolis (Classical)

Workshop of Phidias, Three Goddesses, East Pediment of the Parthenon (Classical)

Lysippos, Weary Herakles (Late Classical)

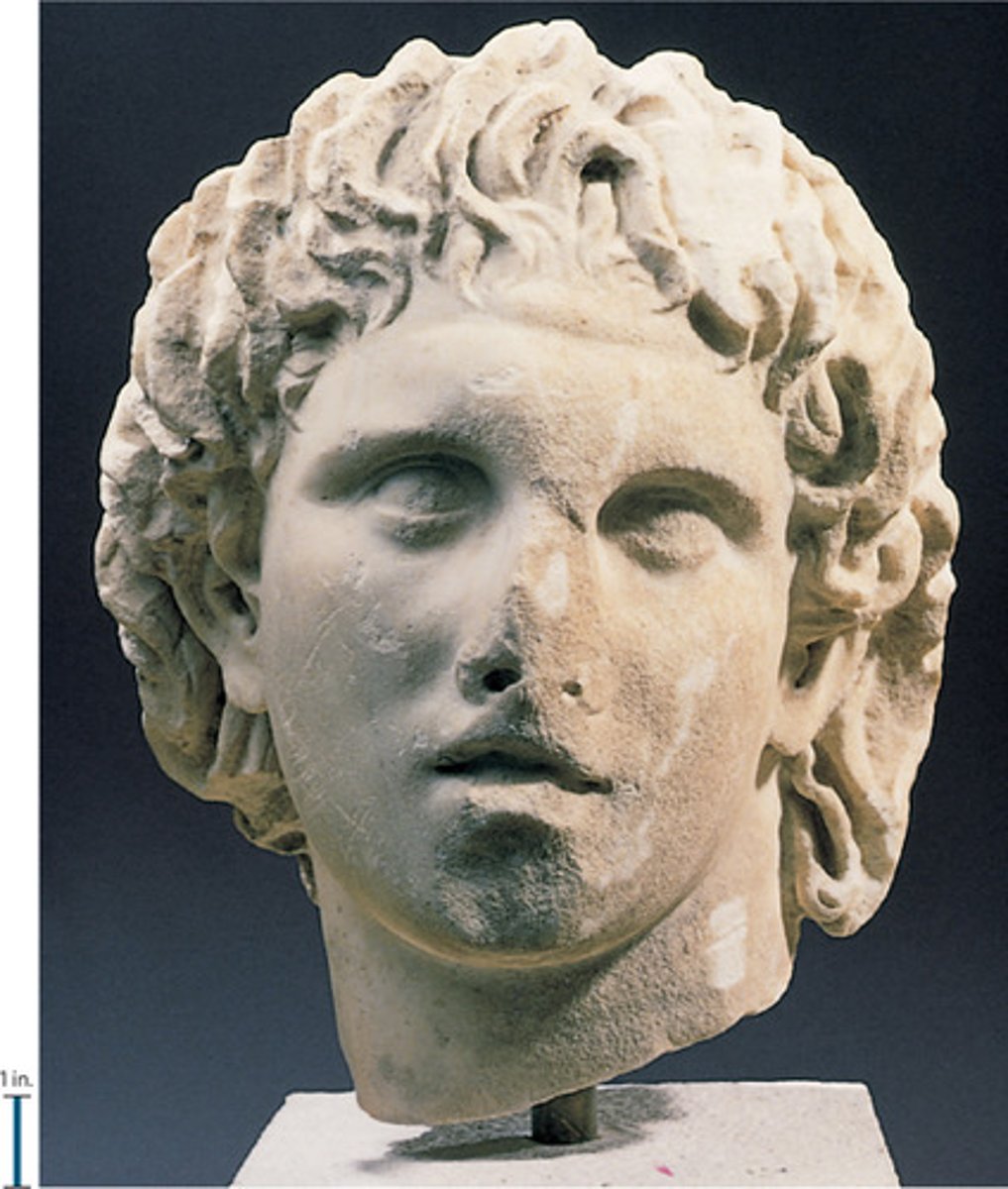

Head of Alexander the Great (Hellenistic)

Philoxenos of Eretria, Battle of Issus (Hellenistic)

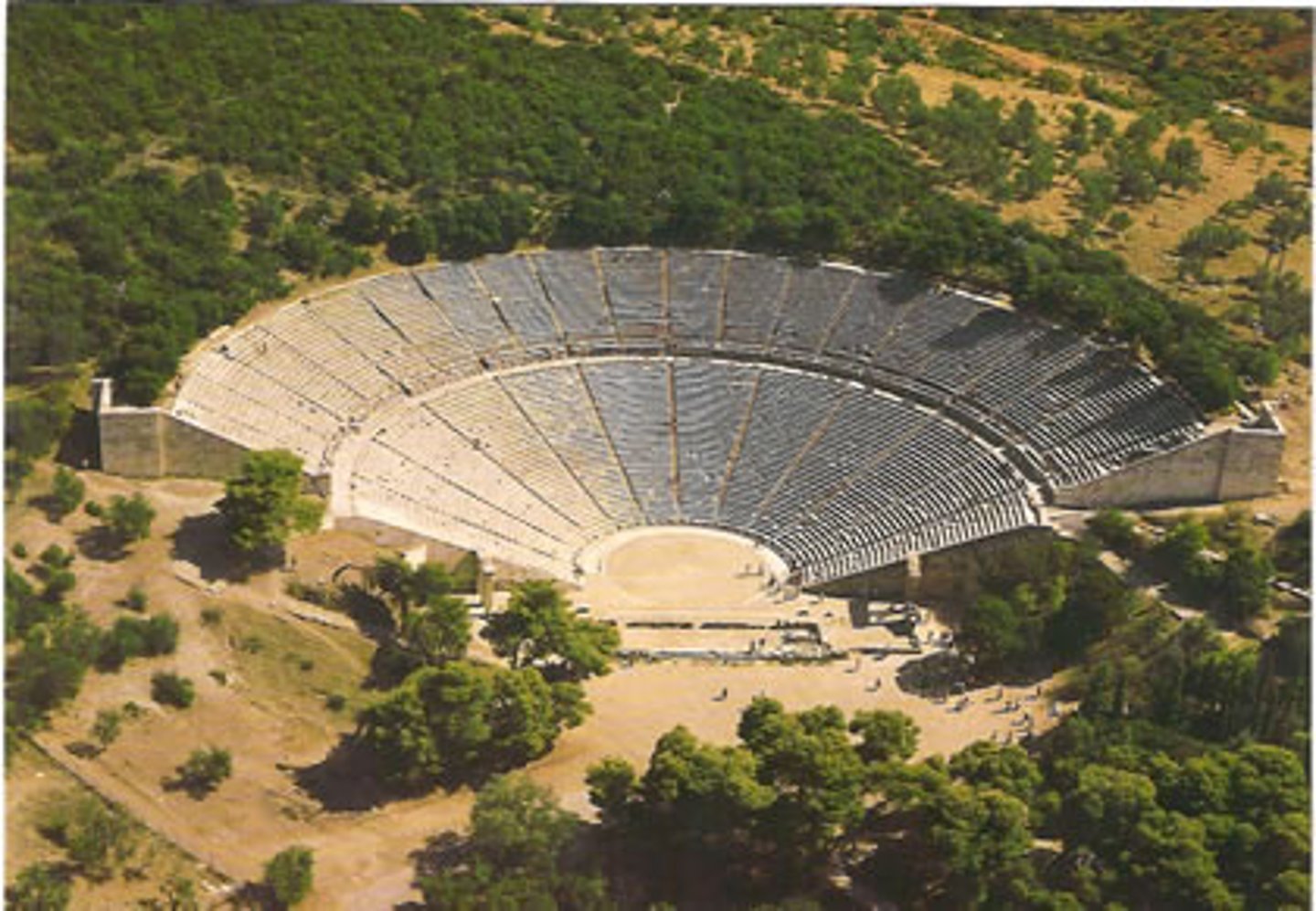

Polykleitos the Younger, Theater at Epidauros (Hellenistic)

Athena Attacking the Giants (Hellenistic)

Nike of Somathrace (Hellenistic)

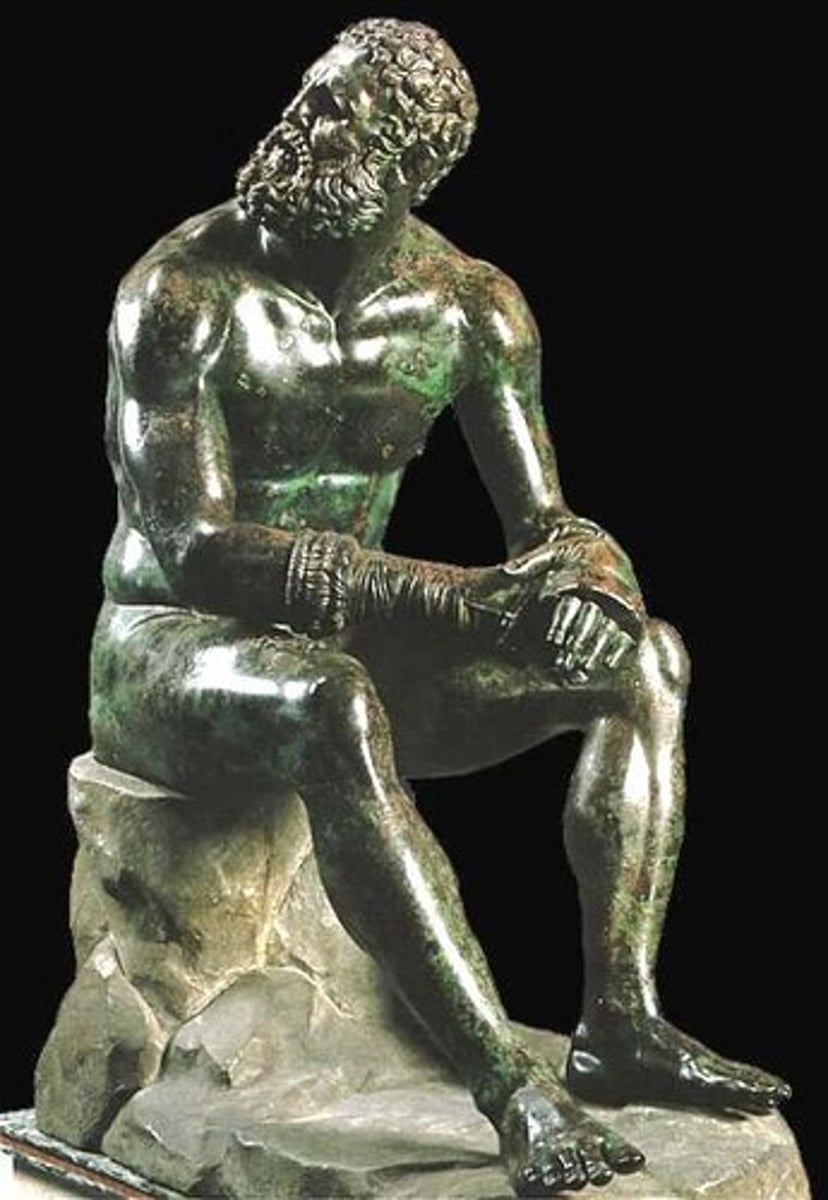

Seated Boxer (Hellenistic)

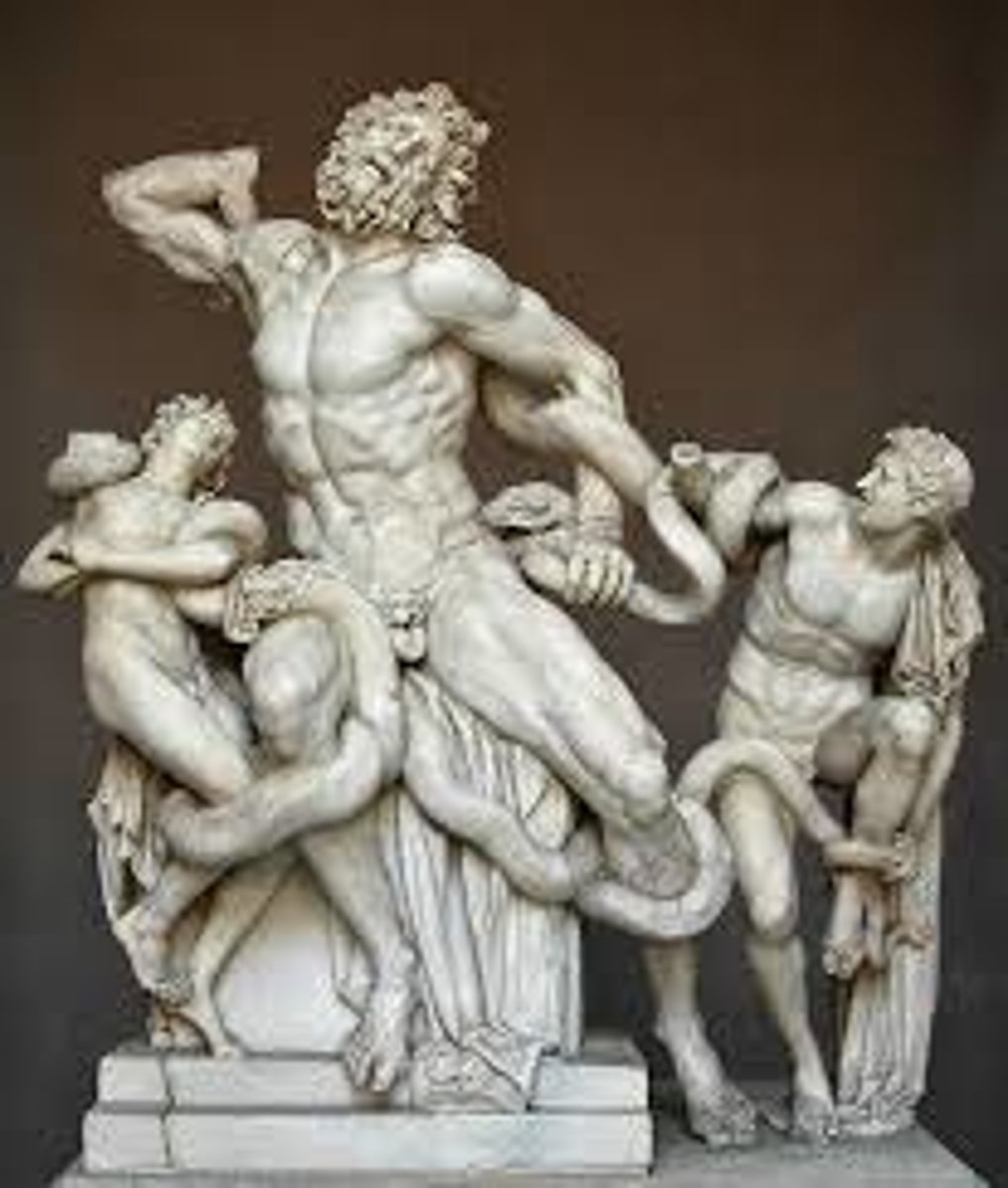

Laocoon (Hellenistic)

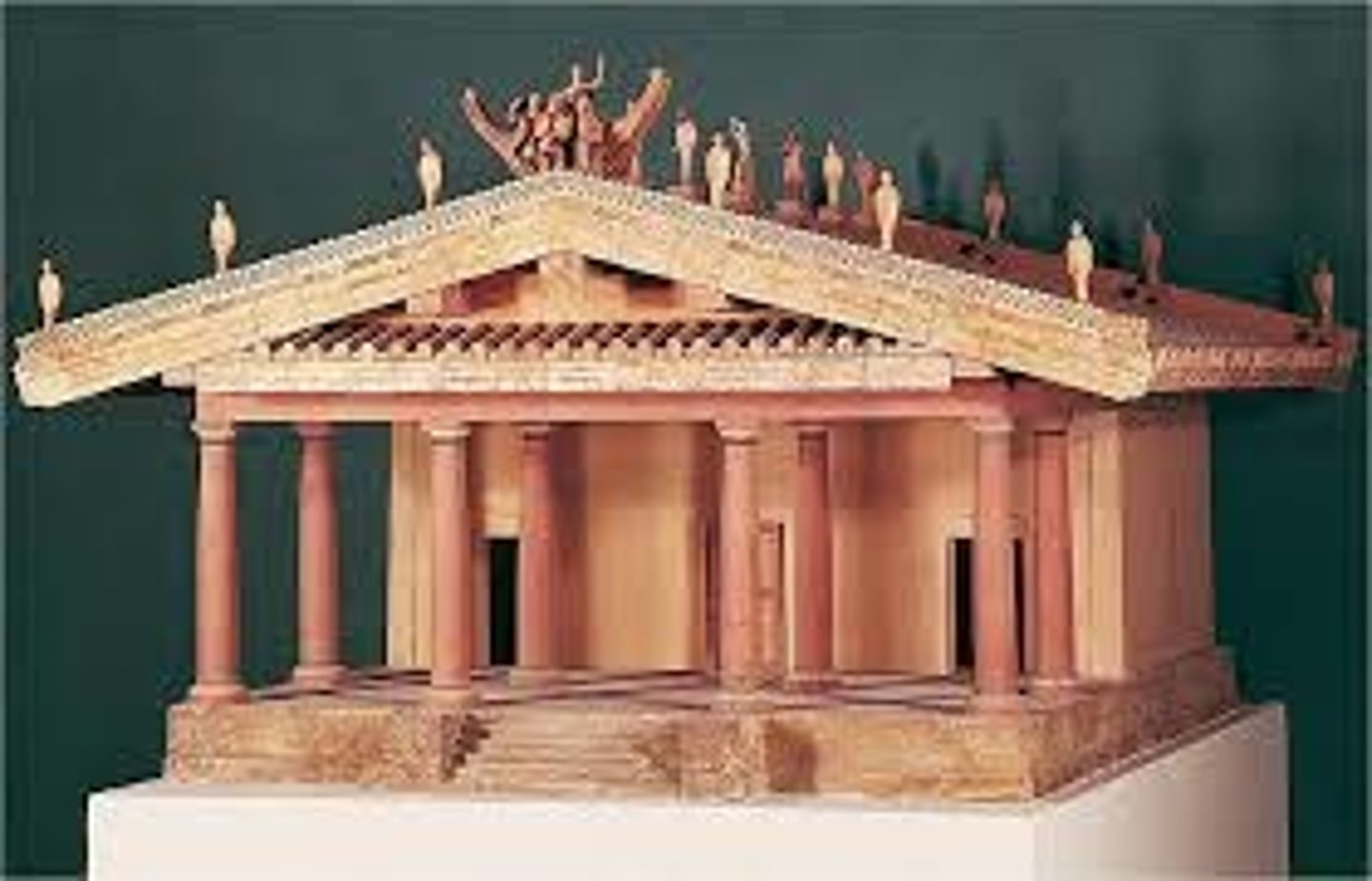

Temple of Veii (Etruscan)

Vulca, Apollo of Veii (Etruscan)

Sarcophagus with Reclining Couple (Etruscan)

Tomb of the Leopards (Etruscan)

The Orator (Etruscan)

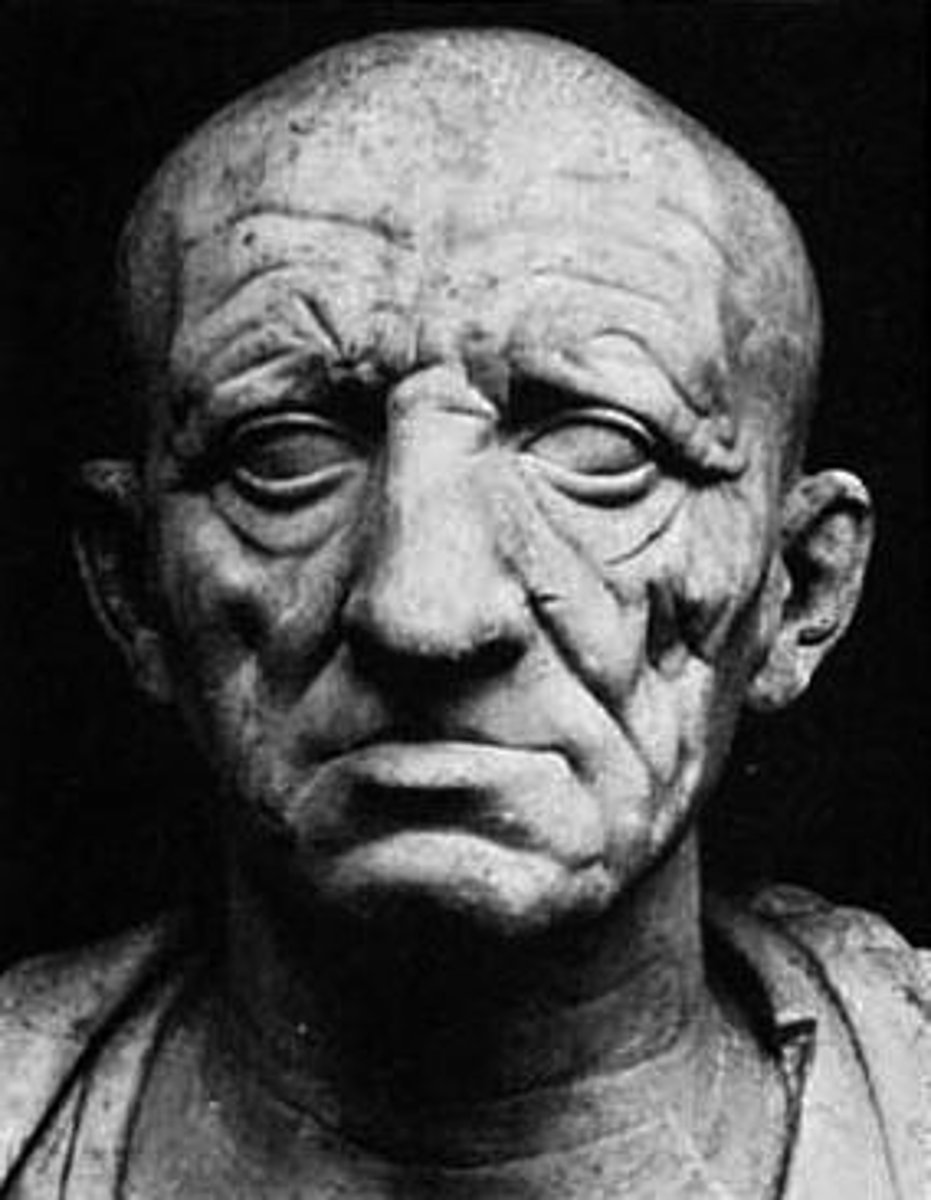

Head of the Roman Patrician (Roman Republic)

Temple of Portunus (Roman Republic)

Pont-du-Gard (Roman Republic)

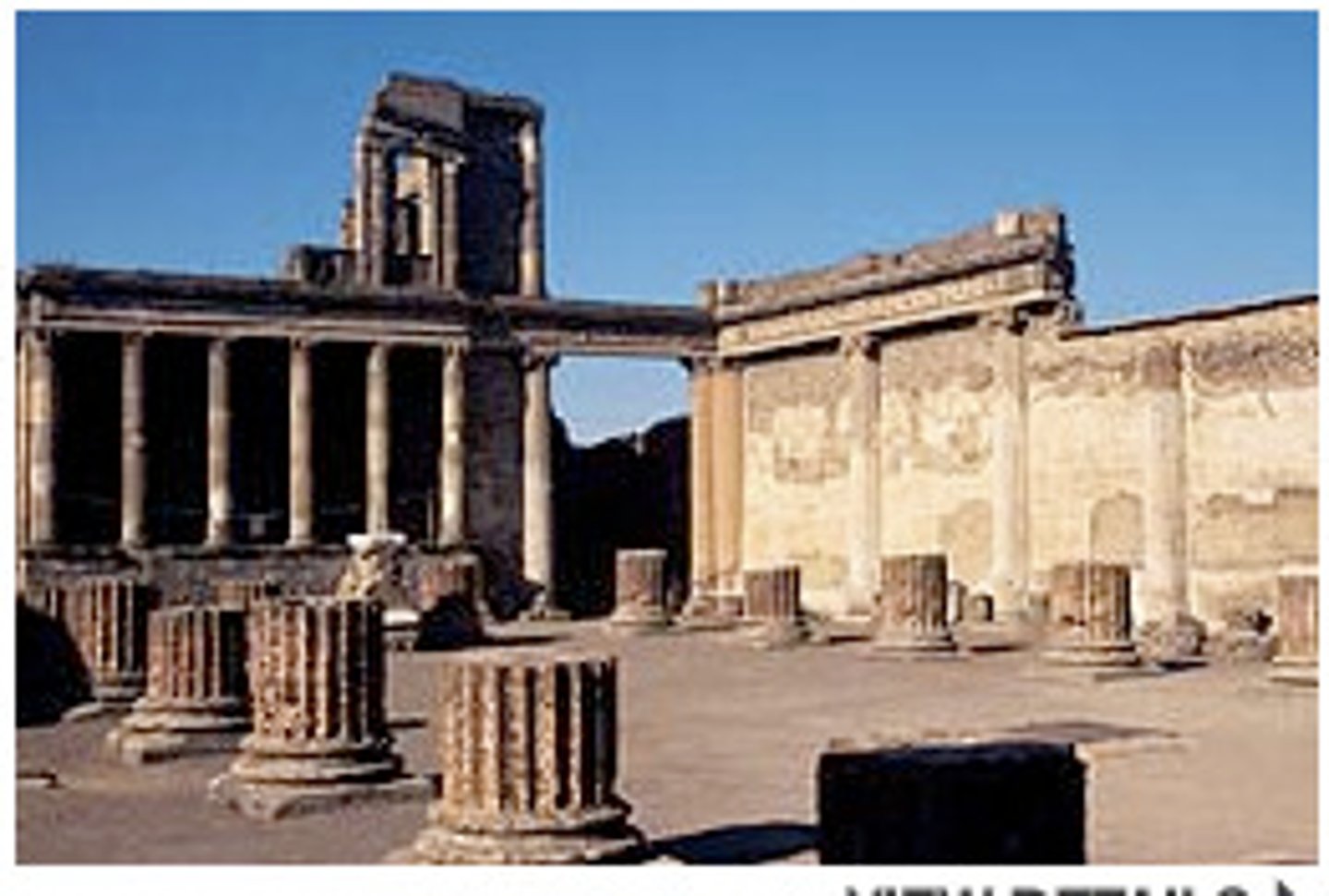

Pompeii basilica (Roman Republic)

Pompeii Forum (Roman Republic)

Roman House at Pompeii (Roman Republic)

Herakleitos, Unswept Floor Mosaic (Roman Republic)

Villa of Mysteries (Roman Republic)

Prima Porta Augustus (Roman Empire)

Colosseum (Roman Empire)

Bust of a Flavian Woman (Roman Empire)

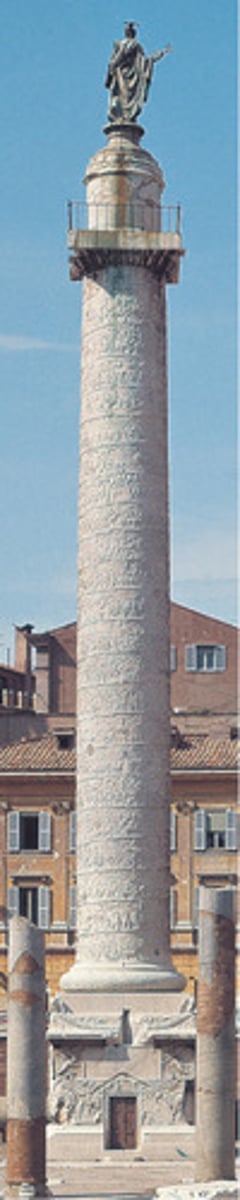

Column of Trajan (Roman Empire)

Pantheon (Roman Empire)

Marcus Araelius Equestrian Statue (Roman Empire)

Orientalizing Art (Oh, Art, Creates, History!)

Context:

Greece was emerging from the “Dark Age” and beginning to trade again with the Near East (Assyria, Phoenicia, Egypt).

This contact brought new motifs and artistic techniques.

Key Features:

Influence: Eastern (Near Eastern and Egyptian) decorative styles — hence the term “Orientalizing.”

Vase painting:

Shift from geometric patterns to floral, animal, and mythological motifs.

Common motifs: sphinxes, lions, griffins, palmettes, and lotuses.

Figures: More natural and detailed than in the earlier Geometric period.

Materials: Introduction of bronze and ivory small-scale sculptures.

Example:

“Eleusis Amphora” (ca. 650 BCE) – early mythological scenes (Odysseus and Polyphemus).

Corinthian pottery is the hallmark — filled with animal friezes and pattern bands.

Archaic Art (Oh, Art, Creates, History!)

Context:

Rise of Greek city-states (poleis), increased wealth, and civic pride.

Growth of monumental stone architecture and sculpture.

Key Features:

Sculpture:

Emergence of kouros (male nude youth) and kore (clothed female) statues.

Figures are rigid and symmetrical, often with the “Archaic smile” — an attempt to animate the face.

Influence from Egyptian stance (one foot forward), but Greek artists explored anatomy more freely.

Vase painting:

Dominated by black-figure technique (black silhouettes on red clay, details incised).

Mythological and narrative scenes become central.

Architecture:

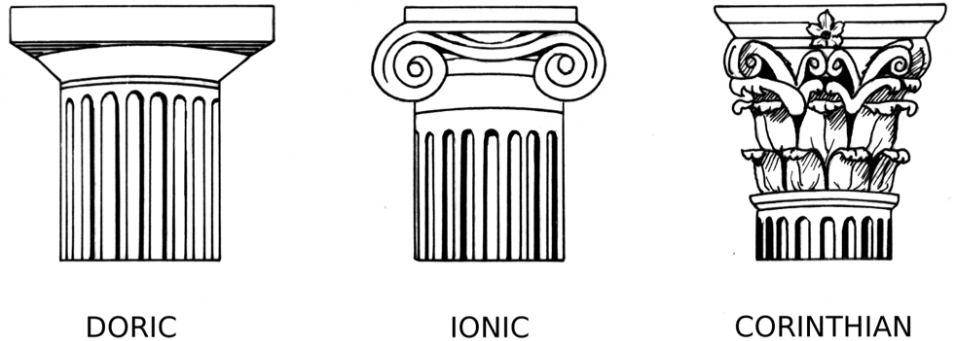

Birth of Doric and Ionic orders.

Example: Temple of Hera I at Paestum.

Examples:

Anavysos Kouros (ca. 530 BCE)

Peplos Kore (ca. 530 BCE)

Exekias, Achilles and Ajax Playing Dice (black-figure amphora, ca. 540 BCE)

Classical Art (Oh, Art, Creates, History!)

Context:

Begins after the Persian Wars; ends with the death of Alexander the Great.

Greece at its political, philosophical, and artistic height.

Humanism, idealism, and balance define the aesthetic.

Key Features:

Sculpture:

Figures become naturalistic and idealized — proportion, harmony, and the beauty of the human body.

Introduction of contrapposto (natural weight shift).

Sculptors seek the ideal human form rather than realism.

Architecture:

Refinement of the Doric and Ionic orders.

Balance, proportion, and mathematical precision.

Example: The Parthenon (447–432 BCE).

Vase painting:

Red-figure technique (reversing black-figure) allows greater detail and realism in anatomy and perspective.

Examples:

Kritios Boy (ca. 480 BCE)

Doryphoros (Spear Bearer) by Polykleitos (ca. 450–440 BCE)

Parthenon sculptures by Phidias (ca. 440 BCE)

Hellenistic Period (Oh, Art, Creates, History!)

Context:

Begins after Alexander’s conquests; Greek culture spreads across a vast empire (from Greece to Egypt and India).

Art becomes cosmopolitan, dramatic, and emotional.

Key Features:

Sculpture:

Heightened realism, emotion, and movement.

Interest in individuals, children, the elderly, and the grotesque — not just idealized youths.

Dynamic compositions and dramatic diagonals.

Architecture:

Grandeur and theatricality; mixture of Greek and Eastern styles.

Painting and mosaics: More perspective and shading — early illusionism.

Examples:

Nike of Samothrace (ca. 190 BCE)

Laocoön and His Sons (ca. 150–100 BCE)

Aphrodite of Melos (Venus de Milo) (ca. 130 BCE)

Pergamon Altar (ca. 175 BCE) – intense movement and emotion.

Three Orders of Columns

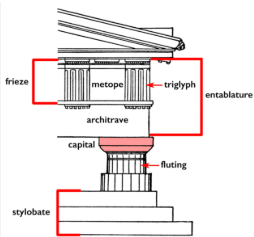

Parts of A Greek Temple

Greek Temples always have stepped fronts, Pediment, Triglyph, and Metope (If its one full story not broken up with T and M then its a Frieze)

Understand the use and difference between the Kore and Kouros figures and know their uses

Kouros (Male Youth)

Nude male statue, standing frontally with one foot forward.

Symbolizes: Ideal youth, strength, and virtue (arete).

Uses:

Grave markers for young men.

Votive offerings to god.

Kore (Female Maiden)

Clothed female statue, standing frontally, often holding an offering.

Symbolizes: Modesty, beauty, and devotion.

Uses:

Votive offerings in temples (often to Athena or Artemis).

Sometimes grave markers.

Example: Peplos Kore (c. 530 BCE).

Both types reflect the Archaic Greek ideal of human perfection and divine beauty, leading toward the more naturalism seen in Classical art.

Parts of a Roman House

Long Essay (INCLUDE FORMAL ANALYSIS)

The Evolution of Architecture: From the Aegean to the Roman Empire

From the early Aegean civilizations to the grandeur of the Roman Empire, architecture underwent remarkable transformation in design, function, and materials. Early structures reflected simple, human-scaled spaces tied to ritual and community, while later monuments became grand, durable, and technologically advanced symbols of civic pride, religion, and imperial power. Each stage of architectural development reflected not only advances in engineering but also shifts in cultural values and how societies viewed humanity’s relationship to the divine and the state.

In the Aegean period, the Palace of Knossos (c. 1700–1400 BCE) on Crete exemplified the complexity and liveliness of Minoan architecture. Built from stone, wood, and mud brick, it featured multi-storied structures, open courtyards, and light wells that emphasized movement and light rather than monumental symmetry. Its design focused on functionality—serving as a political, economic, and religious center—and reflected the Minoans’ appreciation for nature, color, and human activity.

The later Mycenaean civilization shifted toward strength and fortification. The Lion Gate at Mycenae (c. 1250 BCE) served as a massive entrance to the citadel, constructed with huge limestone blocks in a technique known as cyclopean masonry. The triangular relief above the gate—the earliest known monumental sculpture in Europe—demonstrates early architectural symbolism, blending function (defensive power) with artistic expression. This architecture was less open and decorative than Minoan design, reflecting a more militarized society that valued protection and dominance.

With the rise of Greek architecture, design became more standardized and idealized. The Temple of Hera I at Paestum (c. 550 BCE) from the Archaic period exemplifies early Doric temple design: sturdy columns, a low, heavy appearance, and a focus on proportion. It served a purely religious function, honoring a specific deity through symmetrical form and balance. Over time, Greek architecture evolved toward perfection in mathematical proportion, as seen in the Parthenon (c. 447–432 BCE) on the Athenian Acropolis. Built under Pericles’ leadership using marble, the Parthenon embodied Classical ideals of harmony, order, and civic pride. Its precision in design and the optical refinements of its columns show the Greek belief that architecture could express human rationality and divine perfection.

The Etruscans, heavily influenced by Greek models, adapted architecture to suit their own religious practices. The Etruscan Temple at Veii (6th century BCE), for example, had a deep front porch, high podium, and a focus on frontality. Made of wood, mud brick, and terracotta, it emphasized ritual approach rather than symmetry. Unlike the Greek temple, which could be viewed from all sides, the Etruscan temple guided worshippers toward a single, dramatic entryway, setting the stage for later Roman temple designs.

As the Romans inherited and expanded on Etruscan and Greek traditions, they introduced new engineering methods and materials that revolutionized architecture. The Temple of Portunus (late 2nd century BCE) in Rome demonstrates this transitional phase—combining Etruscan frontality with Greek Ionic columns, but constructed from stone and stucco for greater permanence. This blending of styles reflected the Romans’ practicality and cultural inclusiveness.

Roman innovation reached new heights with the introduction of concrete, which allowed for unprecedented scale and flexibility. The Colosseum (72–80 CE) exemplifies this revolution. Designed for public entertainment, it combined arches, vaults, and concrete to accommodate tens of thousands of spectators. Its function shifted architecture from religious and civic ceremony to mass public experience, reflecting Rome’s social organization and engineering mastery.

Finally, the Pantheon (118–125 CE) under Emperor Hadrian represents the pinnacle of Roman architectural achievement. Its massive concrete dome and oculus created an interior space that felt infinite and divine. Combining Greek temple form with Roman engineering, the Pantheon transcended traditional function—it was both a temple for all gods and a symbolic statement of Rome’s cosmic order. The use of lighter concrete toward the dome’s apex demonstrated material sophistication and artistic ingenuity.

From the light-filled palaces of the Minoans to the monumental temples and domes of Rome, architecture evolved in both purpose and possibility. Early builders focused on utility and connection to nature, while later architects sought permanence, perfection, and grandeur. Materials advanced from stone and wood to marble and concrete, enabling new shapes, spaces, and functions. Ultimately, this evolution reflects the growing ambition of human civilization itself—each culture building not only with stronger materials, but with a stronger vision of humanity’s place in the world.

Alexander the Great and his influence on the Greek World at Large

Alexander the Great (356–323 BCE) was the King of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in history, stretching from Greece to India. His conquests spread Greek language, art, and culture across the known world, beginning the Hellenistic Age. By founding cities like Alexandria and encouraging cultural blending, he transformed Greece from a regional power into a global civilization whose influence lasted for centuries.

Understand the function and importance of the acropolis, specifically the acropolis in Athens, including buildings such as the Parthenon

The Acropolis of Athens served as the religious and ceremonial center of the city, symbolizing the power, wealth, and cultural achievement of Athens during its Golden Age. Built on a high hill overlooking the city, it was dedicated primarily to Athena, the city’s patron goddess.

The Parthenon, the most famous building on the Acropolis, functioned as both a temple to Athena and a treasury. Its perfect proportions and sculptural decorations celebrated Athenian ideals of beauty, order, and civic pride. Other structures, like the Erechtheion and the Temple of Athena Nike, also honored the gods and commemorated Athenian victories. Overall, the Acropolis stood as a visual expression of Athens’ devotion to the gods and its leadership in art, architecture, and democracy.

Why was Pompeii Important to the Roman Republic

Pompeii was important to the Roman Empire as a prosperous resort for the wealthy, a major commercial and agricultural hub thanks to its fertile volcanic soil, and a center for social and cultural life. It was also a model of Roman urban development, showcasing Roman infrastructure, art, and daily life, making its preservation a unique and invaluable window into the past.

Why were Aquaducts Important

DYNAMIC FUNCTIONALISM Aqueducts are important to art history because they were monumental engineering feats that blended function with aesthetic design, becoming iconic works of art in themselves. They served as powerful symbols of Roman ingenuity, wealth, and imperial power,

Draw Connections from Egyptian Art to Early Greek art

Early Greek art was heavily influenced by Egyptian art, especially in sculpture. Both used rigid, frontal poses, symmetry, and idealized forms. For example, Egyptian statues of pharaohs inspired Greek kouros figures, which adopted the stance with left foot forward and arms at the sides. While Egyptian art focused on permanence and religious function, Greek artists gradually added naturalism, movement, and individuality, turning these conventions toward human-centered, votive, and funerary purposes.

Be able to explain the importance of perfection and proportion and drapery in Greek statuary

In Greek statuary, perfection and proportion were central because they reflected the Greeks’ belief that physical beauty mirrored moral and intellectual virtue. Sculptors like Polykleitos developed mathematical systems (e.g., the Canon) to create idealized, harmonious figures that embodied balance, order, and human excellence.

Drapery was equally important because it revealed the human form beneath while adding a sense of movement and realism. Artists skillfully carved folds of clothing to follow the body’s contours, enhancing naturalism and emphasizing anatomy. Together, perfection, proportion, and drapery allowed Greek statues to celebrate both the beauty and potential of the human body, blending idealism with lifelike detail.

Classical Greece

Classical Greece starts with the defeat of the Persian invaders of Greece by the allied Hellenic city-states

Naturalism

High point of Greek Civilization

Canon of Polykleitos – Use of the Golden Mean

Sophrosyne = Perfect Harmony and Balance

Mathematical, Idealized Beauty

“Man is the Measure of All Things”

Know the importance of pottery, the use thereof, and the story of the Origin of Painting by Pliny the Elder

In Greek art, pottery was extremely important because it served both practical and artistic purposes. Vases, bowls, and other vessels were used for everyday activities—like storage, drinking, and mixing wine—but they were also canvases for storytelling. Artists painted scenes from mythology, daily life, and athletic contests, preserving cultural narratives and values for both the living and the afterlife.

The Origin of Painting, as told by Pliny the Elder, highlights Greek innovation in art. According to Pliny, the first painting arose when a Corinthian woman traced the shadow of her lover on a wall to capture his likeness. This story illustrates the Greek fascination with representation, realism, and capturing human form, which became central themes in their painting and, later, in sculpture. Together, pottery and this emphasis on representation show how Greek art combined utility, storytelling, and the study of human experience.

Consider how Greek art changed in response to the political turmoil of the empire

Greek art changed significantly in response to political turmoil, especially during the transition from the Classical to the Hellenistic period. In the Classical period, art emphasized balance, harmony, and idealized perfection, reflecting the stability and civic pride of city-states like Athens. However, as wars, conquests, and the eventual fall of Greek independence occurred, artists began to depict more emotional, dramatic, and realistic subjects.

During the Hellenistic period, sculptures such as the Laocoön Group and the Winged Victory of Samothrace captured intense movement, suffering, and human emotion. Art shifted from idealized calm to expressive realism, portraying tension, vulnerability, and personal experience. These changes show how political instability and cultural blending influenced Greek artists to explore the complexities of the human condition rather than just perfect forms.

Etruscan Art

Etruscan tombs often contained sarcophagi made of terracotta, such as the Sarcophagus of the Spouses (c. 520 BCE), which depicts a reclining husband and wife together in a joyful banquet pose. This shows the importance of family, companionship, and the afterlife. Tomb walls were decorated with frescos, like those in the Tomb of the Leopards (c. 480–450 BCE), which show lively banquets, dancing, and musicians. These images were meant to celebrate life, honor the deceased, and provide a comforting, familiar environment in the afterlife.

Verism

In the early Roman Republic, portraiture was characterized by verism, a style that emphasized extreme realism and unidealized features. Unlike Greek Classical art, which celebrated idealized youth and perfection, Roman artists portrayed their subjects with every wrinkle, scar, and imperfection. This approach reflected Roman values such as wisdom, experience, age, and virtue, highlighting the moral authority and social status of elders.

Explain how Romans used art for propaganda

nother example is Trajan’s Column (c. 113 CE), which visually narrates Emperor Trajan’s victory in the Dacian Wars. The detailed reliefs glorify the emperor, his army, and Rome’s power, turning military conquest into a lasting public statement of political dominance.

In short, Roman art functioned as visual storytelling to glorify leaders, legitimize power, and influence public perception—an early form of mass propaganda.

Be able to identify and describe the progression of Roman art and sculpture

1. Early Roman Art (Etruscan Influence, 6th–5th century BCE)

Inspired by Etruscan and Greek art, especially in temples, tombs, and sculpture.

Sculpture was mostly religious or funerary, with rigid forms and simple proportions.

Example: Sarcophagus of the Spouses (terracotta, c. 520 BCE) shows reclining figures in a banquet pose, reflecting Etruscan traditions.

2. Republican Roman Art (509–27 BCE)

Characterized by verism, extreme realism emphasizing age, wisdom, and moral virtue.

Portraits focused on civic values, ancestry, and experience rather than idealized beauty.

Examples: Head of an Old Man from Osimo, Patrician with Busts of His Ancestors.

Funerary art celebrated family lineage and civic responsibility.

3. Early Imperial Art (27 BCE–2nd century CE)

Began with Augustan art, which revived Classical Greek ideals but served propaganda purposes.

Emphasized harmony, balance, and the ruler’s authority.

Example: Ara Pacis Augustae celebrates Augustus’ achievements and the Pax Romana.

4. High Imperial Art (2nd century CE)

Monumental architecture and narrative reliefs dominate.

Art glorified emperors and military victories.

Examples: Trajan’s Column (victory in Dacia), Arch of Titus (commemorates military triumphs).

5. Late Imperial Art (3rd–5th century CE)

More abstract, symbolic, and less naturalistic.

Focus shifted from idealized human forms to conveying imperial authority and religious messages.

Example: Arch of Constantine (c. 315 CE) reuses earlier reliefs but emphasizes symbolic power rather than realism.

Summary: Roman art evolved from Etruscan-inspired rigidity → Republican realism/verism → Imperial idealized propaganda → monumental narrative reliefs → abstract symbolism, reflecting shifts in politics, culture, and societal values.

Humanism and the pursuit of perfection in the human body transformed art, culture, and outlook on life by celebrating human potential, beauty, and virtue. Greek artists emphasized ideal proportions and anatomy, as seen in Kouros statues (c. 600 BCE) and Polykleitos’ Doryphoros (c. 450 BCE), linking physical perfection to moral excellence. The Parthenon friezes (c. 447–432 BCE) celebrated civic pride and human achievement, while Hellenistic works like the Laocoön Group (c. 1st century BCE) explored emotion and struggle, emphasizing individuality. Romans adopted these ideals in Augustan sculptures and public monuments, blending realism and idealism to convey power, virtue, and cultural sophistication. Overall, Humanism shifted focus from the divine to humanity, encouraging people to value knowledge, excellence, and the human experience