Literary + Rhetorical Devices - Vocab Set 3

5.0(1)

Card Sorting

1/39

Earn XP

Description and Tags

82-121

Last updated 11:04 PM on 3/9/23

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

40 Terms

1

New cards

Periodic sentence

When the main idea is not completed until the end of the sentence. The writer begins with subordinate elements and postpones the main clause. (“His confidence broken, his limbs shaking, his collar wet with perspiration, he doubted whether he could ever again appear before an audience.”)

2

New cards

Simple sentence

Contains only one independent clause

3

New cards

Declarative sentence

States an idea. It does not give a command or request, nor does it ask a question. (“The ball is round.”)

4

New cards

Imperative sentence

Issues a command (“Kick the ball.”)

5

New cards

Interrogative sentence

Sentences incorporating interrogative pronouns (what, which, who, whom, and whose) (“To whom did you kick the ball?”)

6

New cards

Style

The choices in diction, tone, and syntax that a writer makes; may be conscious or unconscious.

7

New cards

Symbol

Anything that represents or stands for something else. Usually is something concrete such as an object, actions, character; something that represents another more abstract concept

8

New cards

Syntax / sentence variety

Grammatical arrangement of words. Includes length of sentences, how the length relates to tone and meaning, type of sentence, how sentences relate to each other, etc.

9

New cards

Theme

The central idea or message of a work

10

New cards

Thesis

The sentence or groups of sentences that directly expresses the author's opinion, purpose, meaning, or proposition

11

New cards

Tone

A writer's attitude toward his subject matter revealed through diction, figurative language and organization

12

New cards

Understatement

The ironic minimizing of fact; presents something as less significant than it is (Saying "It’s a bit chilly outside” in below freezing temperatures)

13

New cards

Litotes

A particular form of understatement, generated by denying the opposite of the statement which otherwise would be used (Saying “Their cooking isn’t terrible” to say that someone has good cooking.)

14

New cards

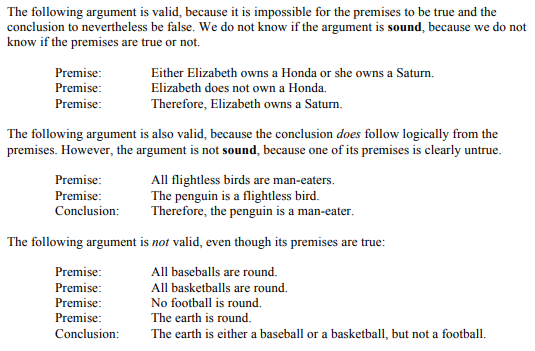

Argument

A piece of reasoning with one or more premises and a conclusion.

(Premise: All Spam is pink.

Premise: I am eating Spam.

Conclusion: I am eating something that is pink.)

(Premise: All Spam is pink.

Premise: I am eating Spam.

Conclusion: I am eating something that is pink.)

15

New cards

Premise

Statements offered as reasons to support a conclusion

16

New cards

Conclusion

The end result of the argument – the main point being made

17

New cards

Aristotle’s appeals

Ethos, pathos, and logos - Used in argumentative writing to persuade an audience that one’s ideas are valid, or more valid than someone else's

18

New cards

Ethos

Persuading by the credibility of the author

19

New cards

Pathos

Persuading by appealing to the reader’s emotions

20

New cards

Logos

Persuading by the use of reasoning, using true premises and valid arguments; strongest appeal

21

New cards

Concession

Accepting at least part or all of an opposing viewpoint. Often used to make one’s own argument stronger by demonstrating that one is willing to accept what is obviously true and reasonable, even if it is presented by the opposition.

22

New cards

Conditional statement

An if-then statement consisting of two parts, an antecedent and a consequent (“If you studied hard, then you will pass the test.”)

Often used as premises in an argument

(Premise: If I study, I will do well on my test. (conditional)

Premise: I have studied.

Conclusion: Ergo, I will do well on the test.)

Often used as premises in an argument

(Premise: If I study, I will do well on my test. (conditional)

Premise: I have studied.

Conclusion: Ergo, I will do well on the test.)

23

New cards

Contradiction

When one asserts two mutually exclusive propositions (“Nobody goes to that restaurant; it is too crowded.”)

24

New cards

Counterexample

An example that runs counter to (opposes) a generalization, thus falsifying it

(Premise: Jane argued that all whales are endangered.

Premise: Belugas are a type of whale.

Premise: Belugas are not endangered.

Conclusion: Therefore, Jane’s argument is unsound.)

(Premise: Jane argued that all whales are endangered.

Premise: Belugas are a type of whale.

Premise: Belugas are not endangered.

Conclusion: Therefore, Jane’s argument is unsound.)

25

New cards

Deductive argument

An argument in which it is thought that the premises provide a guarantee of the truth of the conclusion. In a deductive argument, the premises are intended to provide support for the conclusion that is so strong that, if the premises are true, it would be impossible for the conclusion to be false.

26

New cards

Fallacy

An attractive but unreliable piece of reasoning

27

New cards

Ad hominem fallacy

Personally attacking your opponents instead of their arguments. It is an argument that appeals to emotion rather than reason, feeling rather than intellect.

28

New cards

Appeal to authority fallacy

The claim that because somebody famous supports an idea, the idea must be right

29

New cards

Bandwagon fallacy

The claim that something is valid because many people believe or do it

30

New cards

Emotional fallacy

An attempt to replace a logical argument with an appeal to the audience’s emotions

31

New cards

Bad analogy fallacy

Claiming that two situations are highly similar when they aren't (“We have pure food and drug laws regulating what we put in our bodies; why can't we have laws to keep musicians from giving us filth for the mind?”)

32

New cards

Cliche thinking fallacy

Using a well-known saying as evidence, as if it is proven, or as if it has no exceptions

33

New cards

False cause fallacy

Assuming that because two things happened, the first one caused the second one (““Before women got the vote, there were no nuclear weapons. Therefore women’s suffrage must have led to nuclear weapons.”)

34

New cards

Hasty generalization fallacy

A generalization based on too little or unrepresentative data. (“My uncle didn’t go to college, and he makes a lot of money. So, people who don’t go to college do just as well as those who do.”)

35

New cards

Non sequitur fallacy

A conclusion that does not follow from its premises; an invalid argument (“Hinduism is one of the world’s largest religious groups. It is also one of the world’s oldest religions. Hinduism helps millions of people lead happier, more productive lives. Therefore the principles of Hinduism must be true.”)

36

New cards

Slippery slope fallacy

The assumption that once started, a situation will continue to its most extreme possible outcome. (“If you drink a glass of wine, then you’ll soon be drinking all the time, and then you’ll become a homeless alcoholic.”)

37

New cards

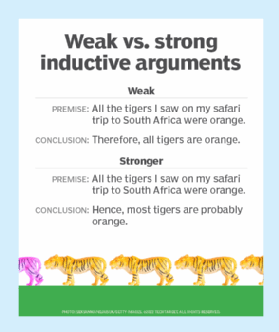

Inductive argument

An argument in which it is thought that the premises provide reasons supporting the probable truth of the conclusion. In an inductive argument, the premises are intended only to be so strong that, if they are true, then it is unlikely that the conclusion is false.

38

New cards

Sound argument

A deductive argument is said to be sound if it meets two conditions: First, that the line of reasoning from the premises to the conclusion is valid. Second, that the premises are true.

39

New cards

Unstated premises

Premises that a deductive argument requires, but are not explicitly stated

40

New cards

Valid argument

An argument is valid if the conclusion logically follows from the premises