Unit 4: Systems of Particles and Linear Momentum

4.1: Center of Mass

The center of mass is the point where all of the mass of an object can be considered to be concentrated; it’s the dot that represents the object of interest in a free-body diagram.

For a homogeneous body (that is, one for which the density is uniform throughout), the center of mass is where you intuitively expect it to be: at the geometric center. Thus, the center of mass of a uniform sphere or cube or box is at its geometric center.

If we have a collection of discrete particles, the center of mass of the system can be determined mathematically as follows.

First consider the case where the particles all lie on a straight line. Call this the x-axis.

Select some point to be the origin (x = 0) and determine the positions of each particle on the axis.

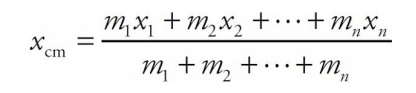

Multiply each position value by the mass of the particle at that location, and get the sum for all the particles. Divide this sum by the total mass, and the resulting x-value is the center of mass:

The system of particles behaves in many respects as if all its mass,

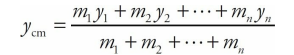

M = m1 + m2 +···+ mn, were concentrated at a single location, xcm.If the system consists of objects that are not confined to the same straight line, use the equation above to find the x-coordinate of their center of mass, and the corresponding equation,

- to find the y-coordinate of their center of mass (and one more equation to calculate the z-coordinate, if they are not confined to a single plane).

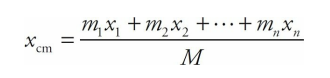

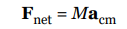

From the equation

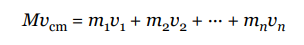

we can derive

So, the total linear momentum of all the particles in the system

(m1v1 + m2v2 +…+ mnvn )is the same as Mvcm, the linear momentum of a single particle (whose mass is equal to the system’s total mass) moving with the velocity of the center of mass.We can also differentiate again and establish the following:

This says that the net (external) force acting on the system causes the center of mass to accelerate according to Newton’s Second Law.

Sample Problem

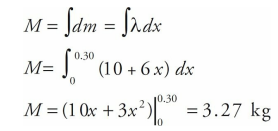

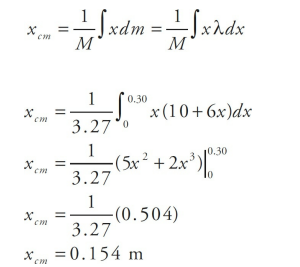

A bar with a length of 30 cm has a linear density λ = 10 + 6x, where x is in meters and λ is in kg/m. Determine the mass of the bar and the center of mass of this bar.

Solution

We can determine the mass of the bar by using the definition of linear density, therefore..

To calculate the center of mass, we will use this equation:

Motion of the Center of Mass

- The center of mass (COM) is the point in a system where the mass can be considered to be concentrated.

- If there is no external force acting on a system, the COM will remain at rest or move with a constant velocity.

- If there is an external force acting on a system, the COM will accelerate in the direction of the force.

- The acceleration of the COM is related to the net force acting on the system and the total mass of the system through the equation F = ma, where F is the net force, m is the total mass, and a is the acceleration of the COM.

- The motion of the COM can be used to analyze the motion of a system as a whole, rather than analyzing the motion of each individual particle in the system.

- The motion of the COM can also be used to determine the stability of a system. A system is stable if the COM is at a low point in its potential energy, and unstable if the COM is at a high point in its potential energy.

Center of Gravity vs Center of Mass

- Center of Gravity

- The center of gravity is the point where the weight of an object is evenly distributed in all directions.

- It is the point where the object can be balanced perfectly.

- It is the point where the gravitational force on the object is concentrated.

- It is dependent on the distribution of mass and the gravitational field.

- Center of Mass

- The center of mass is the point where the mass of an object is evenly distributed in all directions.

- It is the point where the object can be balanced perfectly.

- It is the point where the gravitational force on the object is concentrated.

- It is dependent on the distribution of mass only.

- Difference between Center of Gravity and Center of Mass

- The center of gravity is dependent on both the distribution of mass and the gravitational field, while the center of mass is dependent only on the distribution of mass.

- The center of gravity is used in statics, while the center of mass is used in dynamics.

- The center of gravity can change with the position of the object, while the center of mass remains constant.

- The center of gravity is used in engineering and design, while the center of mass is used in physics and mechanics.

4.2: Impulse and Momentum

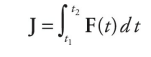

The product of force and the time during which it acts is known as impulse; it’s a vector quantity that’s denoted by J:

In terms of impulse, Newton’s Second Law can be written in yet another form:

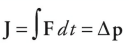

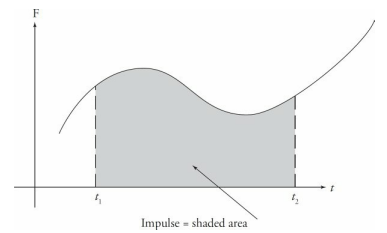

Sometimes this is referred to as the impulse–momentum theorem, but it’s just another way of writing Newton’s Second Law. If F varies with time over the interval during which it acts, then the impulse delivered by the force F = F(t) from time t = t1 to t = t2 is given by the following definite integral:

On the equation sheet for the free-response section, this information will be represented as follows:

If a graph of force-versus-time is given, then the impulse of force F as it acts from t1 to t2 is equal to the area bounded by the graph of F, the t-axis, and the vertical lines associated with t1 and t2 as shown in the following graph.

Sample Problem

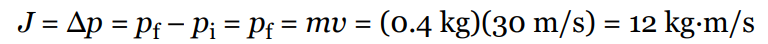

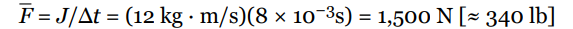

A football team’s kicker punts the ball (mass = 0.4 kg) and gives it a launch speed of 30 m/s. Find the impulse delivered to the football by the kicker’s foot and the average force exerted by the kicker on the ball, given that the impact time is 8 ms.

Solution

Impulse is equal to change in linear momentum, so

Using the equation F = J/Δt, we find that the average force exerted by the kicker is

4.3: Conservation of Linear Momentum

Linear momentum is the product of an object's mass and velocity.

The conservation of linear momentum states that the total momentum of a closed system of objects remains constant if no external forces act on the system. This means that the sum of the momenta of all the objects in the system before a collision or interaction is equal to the sum of the momenta after the collision or interaction.

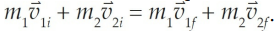

In equation form, for two objects colliding, we have

Conservation of Linear Momentum Sample Problem

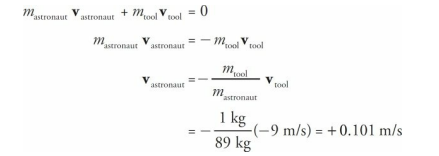

An astronaut is floating in space near her shuttle when she realizes that the cord that’s supposed to attach her to the ship has become disconnected. Her total mass (body + suit + equipment) is 89 kg. She reaches into her pocket, finds a 1 kg metal tool, and throws it out into space with a velocity of 9 m/s directly away from the ship. If the ship is 10 m away, how long will it take her to reach it?

Solution

Here, the astronaut + tool are the system. Because of Conservation of Linear Momentum,

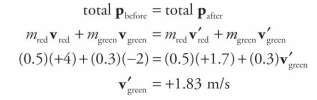

Using distance = average speed × time, we find

Collisions

- The objects whose collision we will analyze form the system, and although the objects exert forces on each other during the impact, these forces are only internal (they occur within the system). The system’s total linear momentum is conserved if there is no net external force on the system.

- Collisions are classified into two major categories: (1) elastic and (2) inelastic. A collision is said to be elastic if kinetic energy is conserved. Inelastic collisions, then, are ones in which the total kinetic energy is different after the collision.

- An extreme example of inelasticism is completely (or perfectly or totally) inelastic.

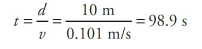

Collisions Sample Problem

Two balls roll toward each other, one red and the other green. The red ball has a mass of 0.5 kg and a speed of 4 m/s just before impact. The green ball has a mass of 0.3 kg and a speed of 2 m/s. After the head-on collision, the red ball continues forward with a speed of 1.7 m/s. Find the speed of the green ball after the collision. Was the collision elastic?

Solution

First remember that momentum is a vector quantity, so the direction of the velocity is crucial. Since the balls roll toward each other, one ball has a positive velocity while the other has a negative velocity. Let’s call the red ball’s velocity before the collision positive; then vred = +4 m/s, and vgreen = –2 m/s. Using a prime to denote after the collision, Conservation of Linear Momentum gives us the following:

Notice that the green ball’s velocity was reversed as a result of the collision; this typically happens when a lighter object collides with a heavier object. To see whether the collision was elastic, we need to compare the total kinetic energies before and after the collision.

In this case, however, an explicit calculation is not needed since both objects experienced a decrease in speed as a result of the collision. Kinetic energy was lost, so the collision was inelastic; this is usually the case with macroscopic collisions.

Most of the lost energy was transferred as heat; the two objects are both slightly warmer as a result of the collision