Neural basis of working memory

1/23

Earn XP

Description and Tags

LTM vs STM, Prefrontal cortex as a possible STM storage buffer, what vs where in WM, evidence from multivoxel pattern analysis against the PFC storage buffer hypothesis. role for the PFC in attention to internal representation

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

24 Terms

recap - HM (1954) - bilateral removal of the temporal lobe

severe amnesia → inability to form long term memories for event & facts

preserved STM memory

preserved LTM memory

recap - Lesion to parietal/occipital cortex (1969)

reduced digit span (STM approx 2 items)

preserved LTM

double dissociation between LTM & STM

key distinction between STM

Fuster (1974)

studied the neural mechanisms of working memory by showing that neurons in the PFC exhibit sustained activity during the delay period of a task where monkeys had to remember the location of food

Neurons in PFC show sustained, elevated response during the delay period of a working memory task

found storage memory happens in dorsolateral pfc

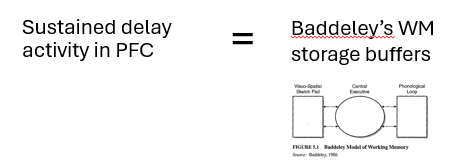

Goldman-Rakic (1987) - standard model of working memory

suggests that this PFC reflects the neuronal instantiation of Baddeley’s working memory storage buffers

sustained activation in PFC during delay period of a WM task reflects a neuronal WM template

a temporary representation of to-be-remembered information

became dominate view of the PFC in working memory for some time

Evidence from monkey neurophysiology for standard model

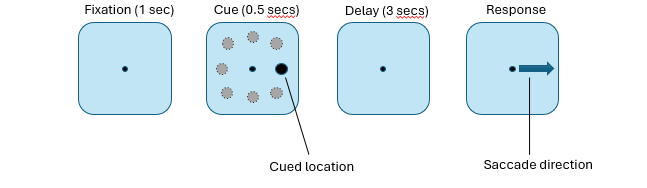

monkey single neuron recordings → oculomotor delayed response task

monkeys saw cue on left/right of fixation & had to maintain their eye gaze at centre for 3 seconds & then make an eye movement in direction of the cue

had to hold direction of cue in their memory for 3 seconds

found that single neurons in PFC showed direction-specific firing during delay period of this task (Between cue & response)

this particular neuron fired strongly when cue pointed to the upper left location

interpret this as showing a direct neurophysiological correlate of WM template, a temporary representation of spatial location indicated by the cue

Supporting human neuropsychological evidence for a role of PFC in working memory (Petrides & Milner 1982)

administered a task called self-ordered task to P w/frontal lobe lesions

P instructed to touch 1 picture per sheet of paper & not to touch the same picture twice until they had through 12 sheets

task requires them to remember from 1 sheet of paper to the next which images they have touched previously

found P w/frontal lobe lesions were disproportionately impaired on this task indicating that P had a deficit w/WM

interpreted this as evidence that the PFC hold representation of to-be-remembered info over short period of a WM

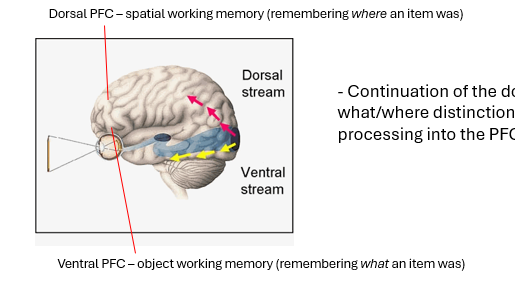

What vs Where in working memory

one of key tenets of the standard model is that there are 2 types of visuospatial WM → one for objects & spatial locations

extended what we know about visual object recognition into PFC

the idea that the 2 visual streams extend into the PFC and enable remembering this information over short periods.

locating objects in space & for identifying objects

The evidence for this idea came predominantly from monkey neurophysiology studies

Evidence from monkey neurophysiology for what/where dissociation in working memory

Majority of evidence for ventral/dorsal dissociation in PFC for objects vs spatial working memory came form monkey

same paradigm of spatial delayed response task but with pattern version → had to remember the identity of the pattern (pockadot = down eye movement)

monkeys were trained to perform an oculomotor delayed response task → saw a cue that instructed them to make an eye movement in a particular direction then had to remember that info before making the response

key change to the task was that in addition to standard spatial cues (a cue appearing in actual location to which monkeys had to make an eye movement) & pattern cues (pattern appeared in centre of screen & instructed monkeys to make an eye movement in a particular direction)

response in both trial types was same but type of information to be remembered on each trial differed.

In spatial trials monkey had to remember spatial location of the cue and in pattern trials monkey had to maintain the identity of the pattern

responses of 2 neurons during delay period during each part of the trial

B = shows response of a neuron in inferior convexity – lower, ventral part of PFC

C = response of a neuron in dorsolateral (upper, dorsal) part of PFC

neuron in inferior ventral PFC shows higher activation to patterns & lower activation to spatial cues

neuron in upper dorsal PFC shows higher activation to spatial cues & lower activation to patterns.

what vs where in working memory → support from PET (courtney et al)

evidence from fMRI for ventral/dorsal what/where distinction in WM

P were required to remember either identity or location of 3 faces & say whether test stimulus matched any of identities or locations

Activation for object WM task was seen in ventral PFC & activation for the spatial WM task was seen in dorsal PFC

Object WM task = remember identities of 3 faces → Activation in ventral PFC

Spatial WM task = remember locations of 3 faces → Activation in dorsal PFC

neural basis of WM → testing the claim that PFC stores temporary representations of remembered info

evidence against the idea PFC stores temporary representations of remembered info

Multivoxel pattern analysis (MVPA)

takes advantage of fine-grained pattern of activation in brain

Uses machine learning techniques to teach an algorithm about pattern of neural activation associated w/particular stimulus

Algorithm is then able to ‘decode’ what the subject is looking at simply by viewing their pattern of brain activity

if PFC is a storage then we should be able to predict

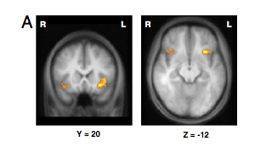

Linden et al (2011) - mapping brain activation & information during category specific visual working memory

P performed task requiring them to memorise/hold several objects in WM

On each trial, required to decide whether a single object was part of the memory set

4 categories of objects – faces, bodies, flowers, scenes

Trained pattern classifier to learn patterns of activation for each category

Tested ability of pattern classifier to predict which category subject was holding in WM on each trial

regions holding category-related information are exclusively in posterior part of brain → visual processing regions e.g fusiform face area & other regions of the ventral visual stream

same regions that are activated when these categories of object are presented to the subjects.

implication of this is that the same regions that enable us to process an object when we see it w/our eyes are also involved in storing temporary representations of those objects in WM

looked at whole brain

can predict what P are holding in the memory

but only in posteier brain regions

PFC does not seem to hold temporary representations of information in WM

These temporary representations appear to be stored in brain regions involved in sensory processing – in this example in the visual cortex

shows us what P are memorising

The implication is that the same regions that enable us to process objects when we see them are also involved in storing temporary representations of those objects in WM

PFC is organised according to a ventral/dorsal distinction for remembering what vs where an object is → evidence for what/where dissociation in working memory (Wilson et al, 1955-8)

neuron in the upper dorsal PFC shows higher activation to spatial cues and lower activation to patterns

Evidence against ventral/dorsal (what/where) distinction in PFC (Rao et al 1997)

There is now a considerable body of evidence supporting this idea – that the PFC does not store representations of stored stimuli.

lots of neurons share activation → flexible response properties which can change depending on task

Some of the most convincing evidence against the standard model originally came from monkey neurophysiology → found that single neurons in PFC can encode both the location of an object & its identity

Monkeys had to remember first identity of an object and make an eye movement to the same object in a different location, and then remember its location. They made an eye movement to the location lacking identity information.

Found that neurons could encode both object identity and location – suggests flexible adaptation of responses in PFC – neurons can adapt to represent whatever information is task relevant.

explaining PFC activation during WM - adaptive coding model of PFC (duncan)

PFC neurons show flexibility in their response tuning

whatever they are doing

unlike neurons in other brain regiosn response propteries of PFC neurons aernot fixed buy adapt to encode currenlty task relevant informaiton

why do we find acrivation in doslateral PFC during spacial → role of chunking (Bor & DUncan, 2003)

structured vs unstructured sequence spatial task

whether sequence forms a shape or not

P try to make it easier for themselves by storing information into a manageable chunk

higher activation in lateral for structured

the role of other processes

just becuase P w/frontal lesions can have issues with task

storage of previously touched item with supression of previously youcheditem

selective attention to a novel item

may enage in planning/stragtergy

Human and monkey studies converge to suggest the PFC is not organised according to the type of stimulus held in WM (what vs where)

In fact PFC may not store information in WM at all. What then is the role of the PFC in WM?

We have seen that the ability to follow complex task rules is a key component of fluid intelligence

can we decode information about items held in WM from patterns of activation in prefrontal/parietal cortex (Riggall & Postle, 2012)

looked into the question of where in the brain different types of information are represented during working memory

They scanned people performing a WM task where they had to memorise a moving dot array, and during the delay period were cued to either remember the direction or the speed of the dots.

Then they were shown a probe that was either a match or mismatch.

The key thing here is that when the cue appeared subjects had to follow a rule (attend to the speed or the direction of the dots in WM) and also hold in WM a specific stimulus (the particular speed at which the dots were moving, or the direction in which they were moving)

They found that they could decode which direction and how fast the dots were moving but only from visual cortex and temporal cortex. PFC provided no information about this.

In contrast, task instructions could be decoded from PFC and parietal regions.

This is consistent with the Linden study – stimulus specific information was stored in posterior, sensory specific cortex. However, information about task rules was stored in frontal and parietal cortex.

can decode from patterns from posterior PFC about what info is being held in wm

alternative view to standard model → WM as emergent property (Postle, 2006)

“If the brain can represent it, the brain can also demonstrate working memory for it.…working memory functions are produced when attention is directed to systems that have evolved to accomplish sensory-, representation-, or action-related functions.

From this perspective, working memory may simply be a property that emerges from a nervous system that is capable of representing many different kinds of information, and that is endowed with flexibly deployable attention”.

WM is a process of internal attention

working memory as attention to internal stimuli

fMRI evidence for internal attention hypothesis of WM (Higo et al. 2011) - consistent with idea of WM being attention for stimuli

provided direct evidence for the idea that the PFC performs an attentional role in WM

P held two objects in WM and were subsequently cued either to maintain both objects (non-selective attention condition) or a single object (selective attention condition) in WM

Finally asked to decide whether any of the objects in an array matched the object(s) they were holding in WM

Activation in PFC was greater for the selective condition than the non-selective condition

Connectivity analysis demonstrated that activation in PFC modulated activation in different occipitotemporal regions depending on which stimulus the subject maintained in WM

Combined TMS/fMRI showed that disruption of PFC activity caused distal effects on occipitotemporal activation, thus establishing direction of causation

PFC seems to send an attentional bias signal to sensory-specific regions to enhance processing of the task-relevant object during WM

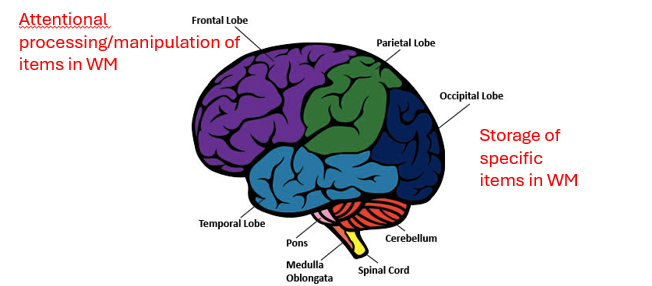

distributed neuronal architecture of WM

lower level visual regions maintain the temporary representations of items held in WM (the templates) and PFC/parietal regions hold a representation of the task rules for manipulating this information (the central executive!)

in posterieror storage of specific items in WM

frontal attentional processing/maniputaltion of items in WM

key points for neuronal WM

PFC neurons show sustained activity during the delay period of a WM task

However, this activity does not reflect storage of items in WM

Representations of items stored in WM are maintained in sensory-specific cortex

PFC seems to play a role in the processing of stimuli held in WM

This role may involve enhancing attention to internal representations of task relevant stimuli in working memory and manipulating such information according to a set of stored task rules

This ability plays a key role in fluid intelligence