Module 12 – Strategic Behavior

1/60

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

61 Terms

Game theory

the study of how people and firms behave when their actions affect others’ payoffs

Strategy

a complete plan of action a player will follow in a game

Payoff

the outcome or reward from a given combination of strategies

Simultaneous-move games

players choose strategies at the same time without knowing what the other will do

Dominant strategy

a strategy that gives a player a higher payoff no matter what the other player does

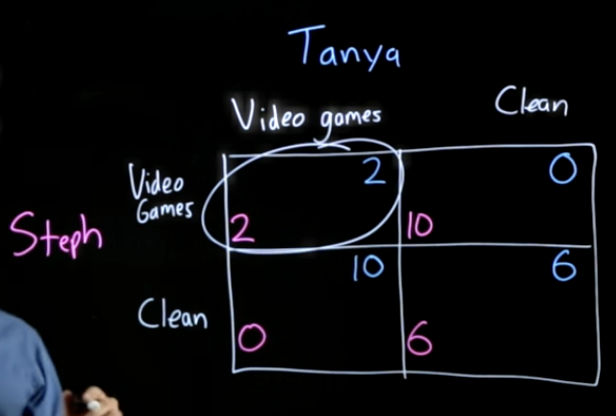

Prisoner’s Dilemma Example

Two friends decide whether to clean or play video games.

Both playing games → low payoff; both cleaning → higher payoff.

Each has incentive to avoid cleaning, so equilibrium ends up with both slacking.

Dominant strategies can lead to

outcomes that are individually rational but socially inefficient

Nash Equilibrium (NE)

a set of strategies where no player can improve their payoff by unilaterally changing their decision

Each player’s choice is the best response to the other’s choice

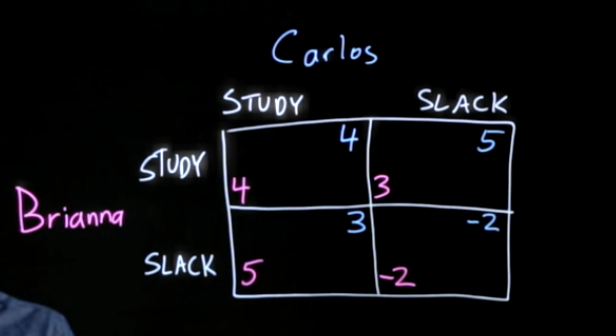

Nash Equilibrium Example (Brianna & Carlos)

deciding whether to study or slack off.

Two Nash equilibria: one studies while the other slacks.

No player has an incentive to switch given the other’s action.

Multiple equilibria

Sometimes, games have more than one NE, leading to coordination problems

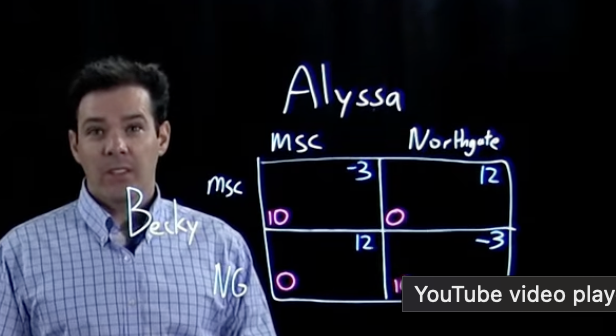

No equilibrium

In some games, there’s no stable solution (players keep switching strategies)

No equilibrium example

Alyssa wants to avoid Becky, Becky wants to follow Alyssa → endless switching, no NE

Nash equilibrium shows stability

not necessarily fairness or efficiency

Nash Equilibrium Example (Yolanda & Zack)

both choose between MSC and Northgate.

Preferences differ, but both want to be together.

Checking each outcome shows Northgate/Northgate is the Nash equilibrium — neither wants to move given the other’s choice

In any game matrix

Identify each player’s best response for each possible action of the other.

The square where best responses intersect is the Nash equilibrium.

Larger games

For games with 3+ strategies, the method is the same — just more options in the matrix

Nash Equilibrium Key Rule

If no player can improve their payoff by switching strategies alone → equilibrium achieved

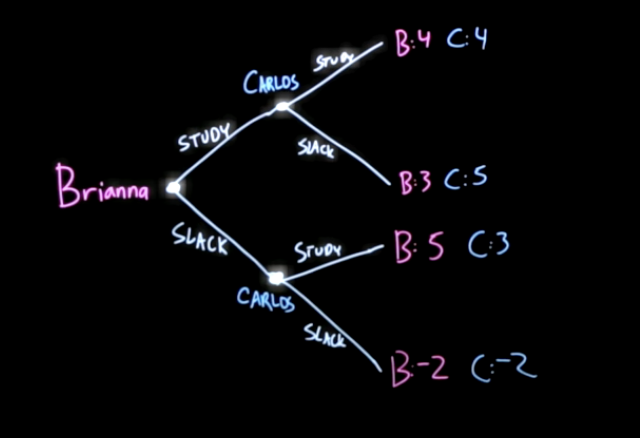

Sequential-move (extensive-form) games

one player moves first, and the other moves after observing that choice

Game trees

diagram that represents the order of moves, possible strategies, and payoffs

Backward induction

solving the game starting from the last mover’s decision

Backward induction Example (Brianna & Carlos)

Brianna moves first; Carlos responds.

Carlos’s best responses: if Brianna studies → he slacks; if Brianna slacks → he studies.

Brianna anticipates this and chooses to slack, while Carlos studies.

Outcome: Brianna (5), Carlos (3) → Nash equilibrium.

First-mover advantage

the first player can shape outcomes to their benefit

Sequential Games Applications

business entry, lending decisions, reputation-building

A “tough reputation”

deters competitors or challenges

Repeated games

same players interact multiple times, allowing reputation and trust to matter

Cooperation

can emerge if players value long-term benefits

Reputation effects

If a player cheats now, future partners may avoid them

Reputation effects examples

Restaurants maintain quality because they want repeat customers

Communication

talking helps coordinate expectations; lack of it can cause misunderstanding or conflict

Social distance

closeness increases cooperation — people trust those similar to them (e.g., Aggies with Aggies)

Dr. Ragan Petrie’s experiment

Showing participants photos of others increased public good contributions by one-third

Social norms

informal rules that govern acceptable behavior

Fairness and the Ultimatum Game

Player 1 (Vince) offers how to split $10 with Player 2 (Rochelle).

Rochelle can accept or reject; if she rejects, both get $0.

Traditional model predicts Rochelle should accept any positive amount, but in practice, offers below 25% are often rejected

Fairness matters

people gain utility from treating others well and punishing unfairness

People maximize utility, not just money

Social trust and fairness improve economic efficiency

Game theory applies to

pricing, quality, and entry decisions

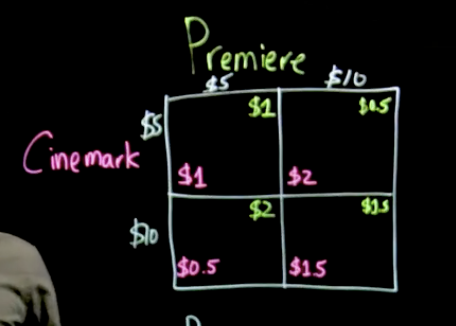

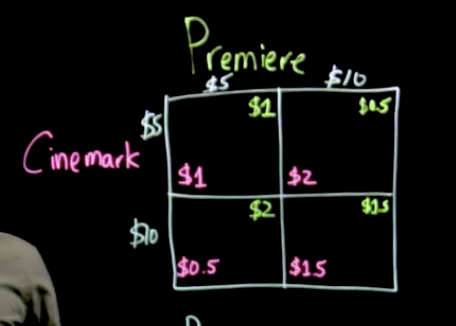

Duopoly Pricing (Simultaneous Game) Example: Cinemark vs. Premiere

Each chooses ticket price: $5 or $10.

If both charge $5 → each earns $1 million.

If one charges $10 while the other charges $5 → high-price firm earns $0.5M; low-price firm earns $2M.

If both charge $10 → each earns $1.5M.

Duopoly Pricing (Simultaneous Game) Nash equilibrium

both charge $5 → each $1M.

Dominant strategy for both is low price.

Consumers benefit, but firms could collude to raise prices to $10 (though illegal)

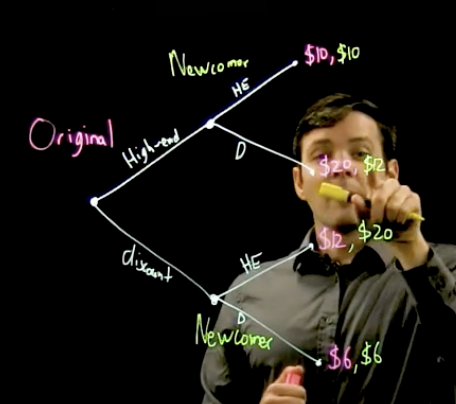

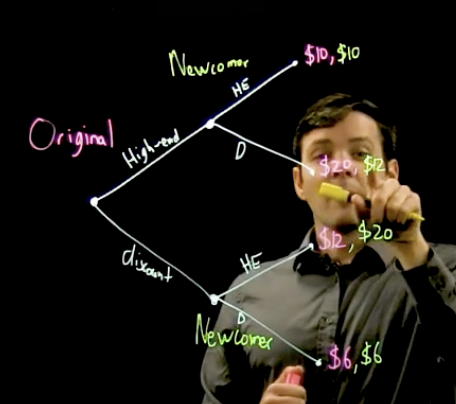

Sequential Game (Entry/Quality Decision) Example: Original & Newcomer

Original (incumbent) moves first, Newcomer (entrant) responds.

If Original chooses high-end clothing, Newcomer responds with discount.

If Original chooses discount, Newcomer goes high-end.

Using backward induction: Original earns $20M by choosing high-end, forcing Newcomer to pick discount.

Sequential Game (Entry/Quality Decision) Outcome

Original gains first-mover advantage; both find stable niches

Game theory clarifies

how firms anticipate rivals’ reactions and position themselves strategically

Traditional models

assume people act rationally to maximize utility

Behavioral economics

studies systematic deviations from rationality

Principles of behavioral economics

People try to choose their best feasible option, but sometimes fail in predictable ways

People care (in part) about how their circumstances compare to reference points

People have self-control problems

Limiting people’s choices could make them better off in theory, but in practice, the record is mixed

Behavioral economics principal 1

People try to choose their best feasible option, but sometimes fail in predictable ways

Behavioral economics principal 2

People care (in part) about how their circumstances compare to reference points

Behavioral economics principal 3

People have self-control problems

Behavioral economics principal 4

Limiting people’s choices could make them better off in theory, but in practice, the record is mixed

Predictable mistakes

People try to optimize but make consistent errors

Overconfidence

underestimate risk, overestimate skill

Availability bias

judge likelihood by how easily examples come to mind (e.g., fear flying > driving)

Reference points and loss aversion

Happiness depends on gains/losses relative to expectations

Loss aversion

losses feel worse than equal-size gains feel good

Anchoring

people rely too heavily on initial numbers (e.g., “original price” framing in sales)

Honoring sunk costs

continuing actions because of past investment (e.g., finishing a bad movie)

Self-control problems

Present bias

Present bias (myopia)

overvalue immediate gratification, undervalue long-term goals.

Explains procrastination, poor saving, and overeating.

Governments and firms

can “nudge” people toward better choices using defaults

Nudge example

organ donation opt-out systems → 90% participation; opt-in → 15%

Policymakers also have biases

paternalism can be overused

Behavioral economics complements not replaces, traditional theory

it deepens understanding of real human behavior