Cognitive; week 5; culture and attention

1/25

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

26 Terms

What is culture?

Way of life of a large group of people in the same geographical location.

Behaviors, beliefs, expectations, values, and interpretations of symbols (language, emojis) that they agree on (often implicitly), passed along by communication and imitation from one generation to the next.

Cultures are dynamic. They change subtly from one area to the next, from one period of time to the next.

Does culture affect cognition? WEIRD populations

Most of psychological sciences are conducted on WEIRD populations:

Western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic societies. Is that a problem?

How do people from different cultures differ in their cognition?

Caution: we need to be careful not to overgeneralize and stereotype. What we’ll talk about are average differences.

Caution 2: Cognition versus performance: experience affects performance in most tasks, but performance is only a marker of cognition (e.g., language production)

Low-level Vs High-level: cognition

Low-level:

perception

attention

encoding

unconscious

inflexible

early evolution

mostly hard-wired

High-level

systematic decision making

brainstorming/ creativity

rule usage

conscious (mostly)

flexible

late evolution

can change

Can culture affect perception? Think of bottom-up and top-down processing

some believe that culture affects cognition at its most basic level

Reminder: social attention = the priority we automatically give to social stimuli, generally considered to be bottom-up

However, top-down influences and experiences can shape even these processes.

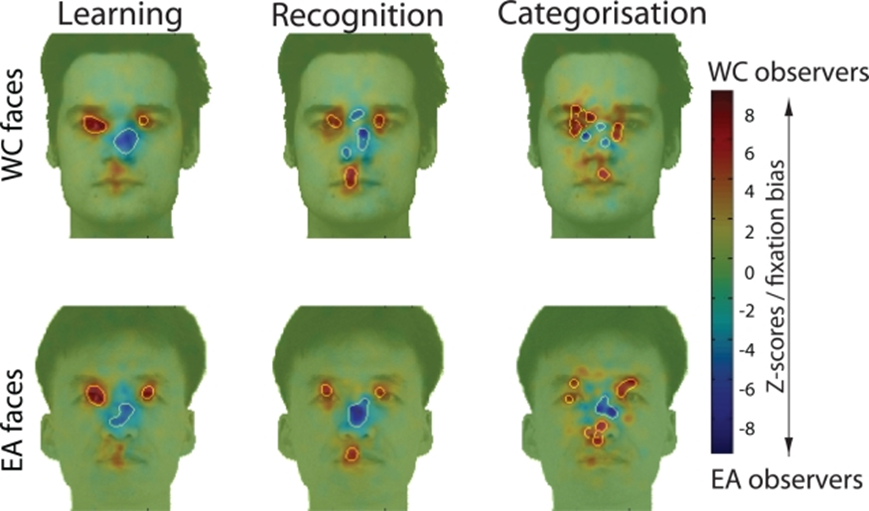

Eye-contact - Western Vs East Asian cultures and Uono & Hietenan (2015)

Direct eye-contact:

encouraged in western societies

may be considered rude in Eastern cultures (especially with elders)

Uono & Hietenan, 2015:

Research question: Does eye contact perception differ in people with different cultural backgrounds?

Finnish (European) vs. Japanese (East Asian)

Task: Is this face looking at you?

results:

Finish participants were more accurate in discerning gaze of Finish faces

Finish participants showed an ‘own-race’ effect – better perception for White European faces

Japanese participants did not show an ‘own race’ effect

Conclusions

Visual experience with Finnish faces throughout development likely led to more effective processing of these faces

Eye contact is quite minimal in Japanese culture so perhaps participants just didn’t have as much experience

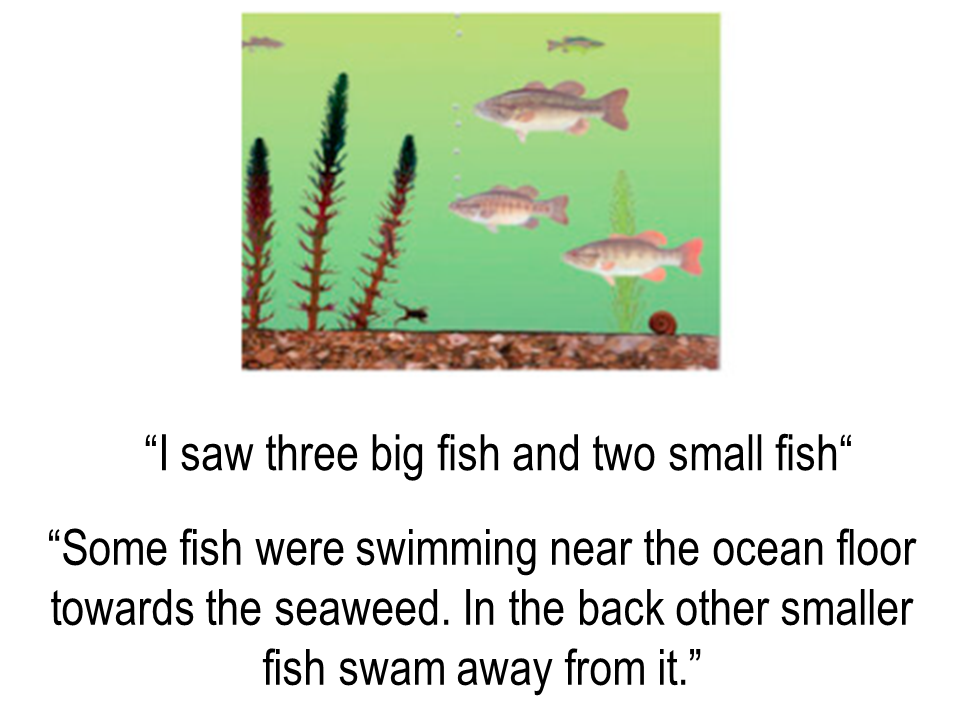

Can culture affect attention more generally? Refer to Masuda and Nisbett

Analytic thinking Vs holistic thinking

Analytic: emphasize a linear object-oriented focus

(dominant in Western Europe and North America)

Holistic: emphasize a non-linear context-oriented focus

(dominant in East Asian cultures such as China, Korea, and Japan)

Masuda and Nisbett, 2001:

finding: Japanese participants were more likely than American participants to make statements regarding contextual information and relationships then

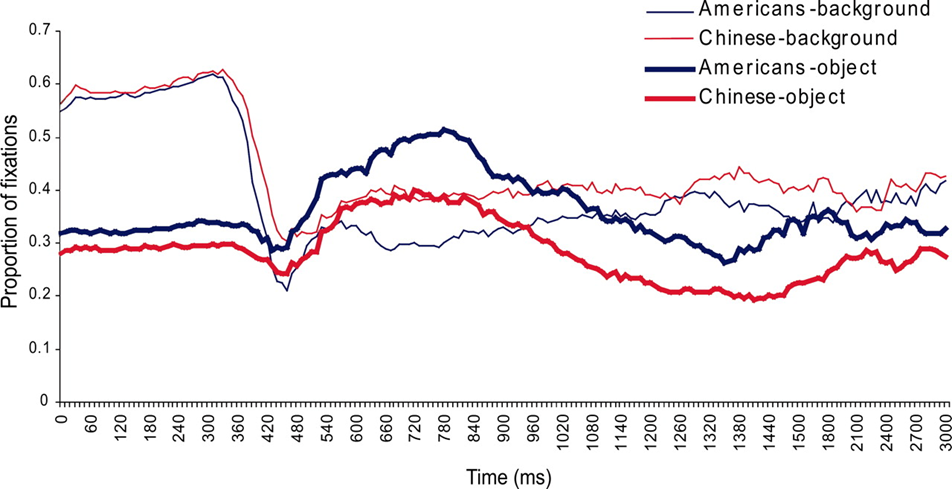

Cultural variation in eye-movements- Chua et al. 2005, what does this mean for eye-gazing?

Cultural variation in eye-movements during scene perception

Chua et al. 2005

results:

“Differences in judgment and memory may have their origins in differences in what is actually attended as people view a scene”

However, Senzaki et al. (2014): Japanese participants’ attention was the same, until they were asked to report what is going on.

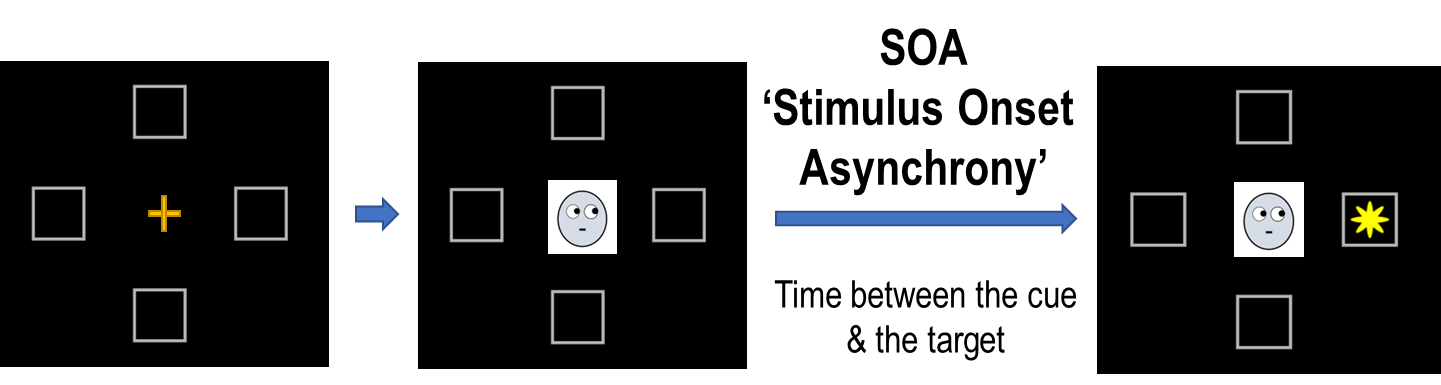

What implications does this have for gaze cueing?

Gaze cueing paradigms typically use short SOAs

Participants show the gaze cueing effect regardless of if the cue is predictive

BUT what if we used a longer SOA that let the participant have time to process the contextual information (i.e. that the cue is non-predictive)?

conclusion: At longer SOAs Japanese participants are better at using contextual information and disengage from the irrelevant gaze

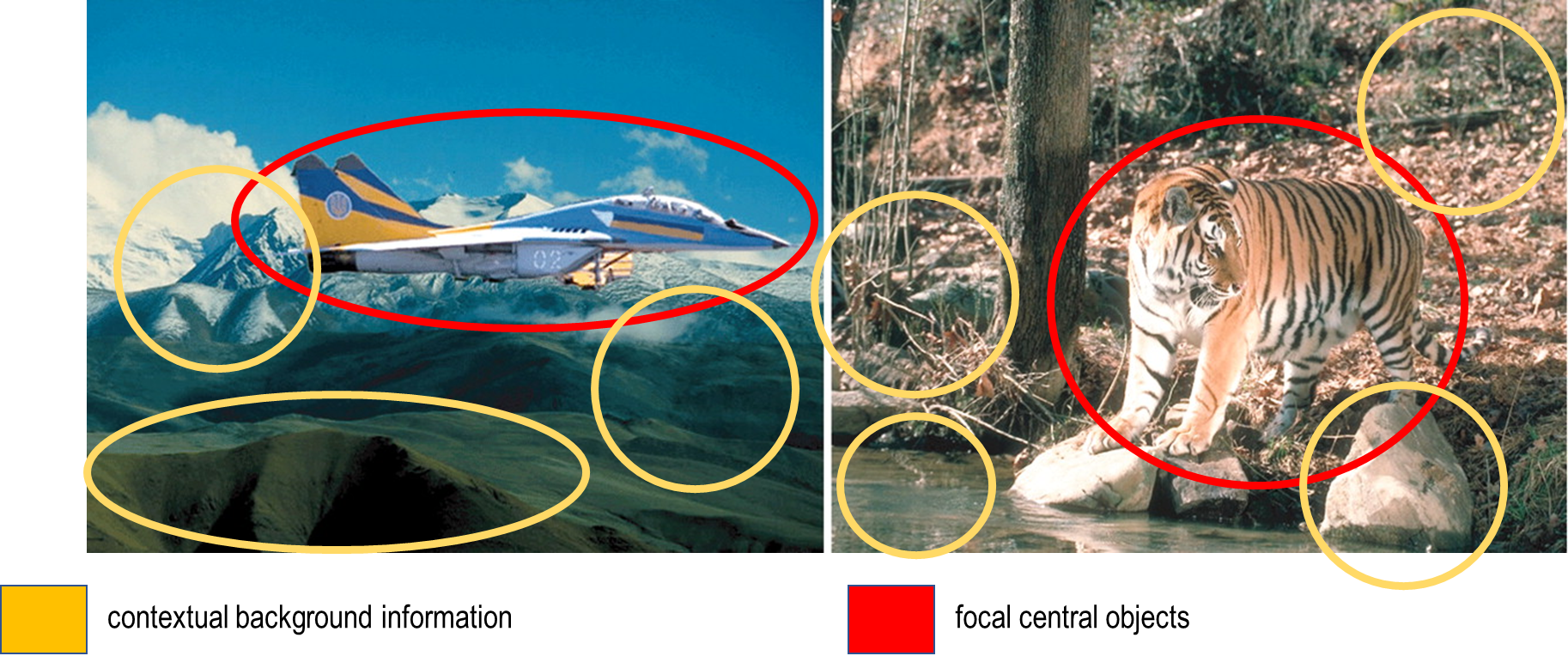

Frame and Line Test (Kitayama et al. 2003)

exposure to society around us plays a role

individuals tended to show the cognitive chracteristic common in the host culture

When do cultural attention-differences develop?

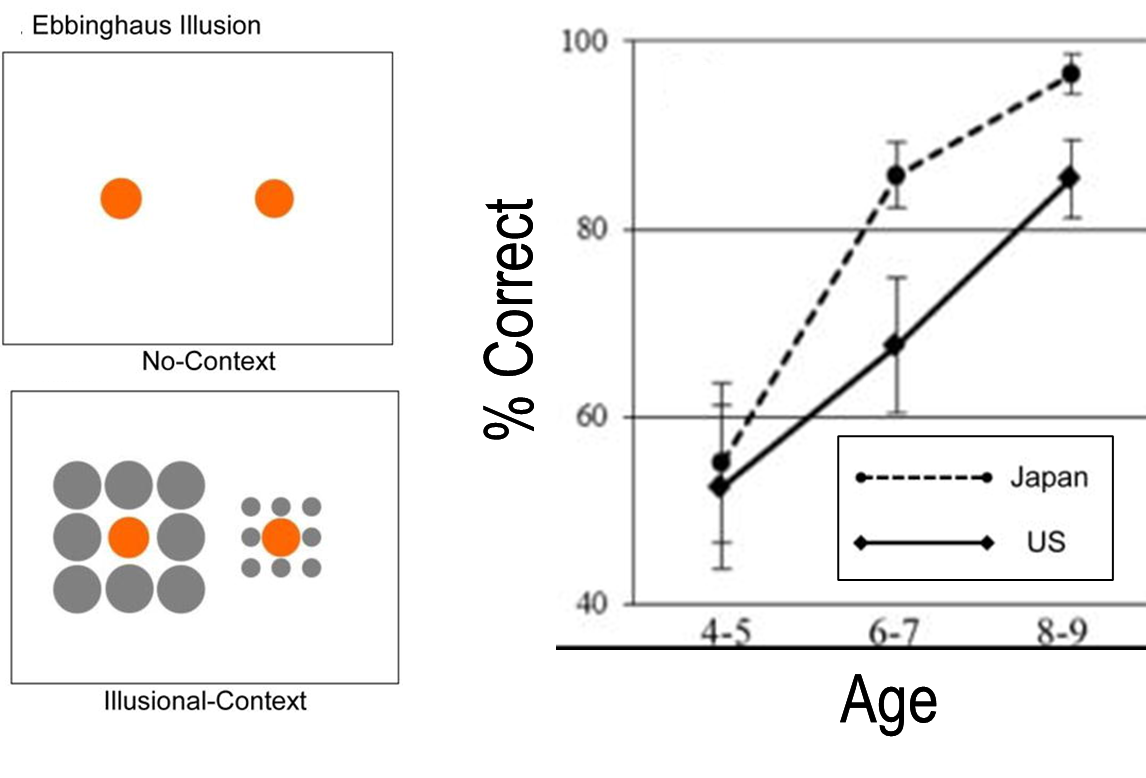

Imada et al., 2013

at age 4-5 children did not show any difference in accuracy

by age 6-7 Japanese children showed better performance, indicating higher context sensitivity

Culture and the physical environment: holistic vs analytic perceptual affordances

Affordance: property of an object that defines its possible uses

Are culturally specific patterns of attention afforded by the perceptual environment of each culture?

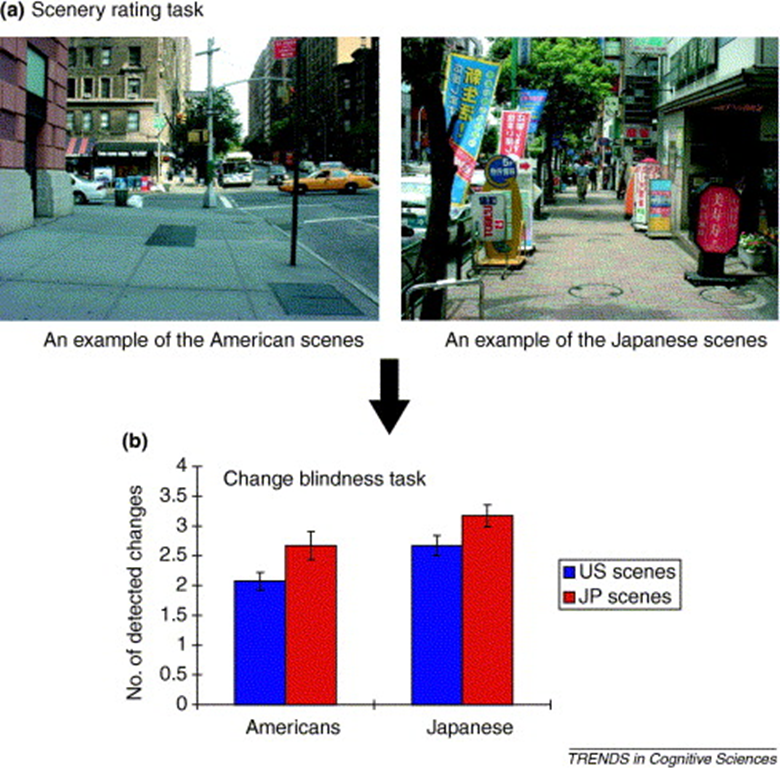

Study 1: Scene perception study

Conclusion: Japanese city scenes are more complex and ambiguous than American city scenes, suggesting that objects look more embedded in the field in the Japanese perceptual environment.

Study 2 change blindness task

Miyamoto et al. 2006

Japanese participants were more likely to detect the change (as they attend more to contextual information)

Both Japanese and American participants who viewed scenes from Japanese cities were more able to detect changes

Japanese cities helped participants attend to more contextual information.

“Culturally characteristic environments may afford distinctive patterns of perception”

Lecture Summary

Initial response to stimuli is the same (bottom-up) but modulated later, based on the task

Culture shapes how we attend to information

Westerners and East Asians attend more likely to attend analytically and holistically:

Differences are both social and non-social

Easterners tend to take more consideration of contextual information than Westerners

Default patterns of attention can be modified

Cognitive psychology paradigms can help to both reveal and improve understanding of cultural differences

Reading- PERCEIVING AN OBJECT AND ITS CONTEXT IN DIFFERENT CULTURES: A Cultural Look at New Look: Abstract

Although perception depends on sensory input, it also involves top-down processes automatically recruited to actively construct a conscious percept from the input. This thesis is called New Look from the 1950s, and is modified by

expectations,

values,

emotions,

needs,

other factors endogenous to the perceiver

Exogenous factors, like physical properties of the impinging stimulus, cannot account for the emerging percept. In large, however, this literature has ignored culture.

Ideational resources (e.g., lay theories, images, scripts, and worldviews) that are embodied in public narratives, practices, and institutions of given geographic regions, historical periods, and groups, whether ethnic, religious, or culture may be expected to be the most fundamental source, of each person’s values, expectations, and needs. The purpose of the current work was to take a renewed look at the New Look from a cultural point.

Reading- Culture and cognition

A conjecture from the literature is that the cross-culturally divergent modes of cognitive processing must be differentially advantageous, depending on the demands of a particular task.

Some tasks require ignoring contextual information when making a judgment about a focal object. For example, a judgment about another person may often be tainted by wrong stereotypes associated with the person’s group. In these circumstances, it is necessary to discount any such stereotypes.

The RFT has no obvious social elements. In contrast, other tasks require incorporating contextual information. For example, a judgment about another person often benefits from attention duly given to the specific social situation in which that person behaves. These tasks may be called relative tasks in that the focal judgment must change in accordance with the relevant context. One might expect that Asians with contextual sensitivity would have an advantage over North Americans in performing such tasks. The evidence supporting this prediction comes exclusively from social domains. Thus, it is well known that North Americans often fail to give proper weight to significant contextual information in drawing a judgment about a focal person. This bias, called the fundamental attribution error, is typically weaker in Asian cultures.

persons engaging in Asian cultures

persons engaging in Asian cultures (Asians, in short) are hypothesized to be attuned more to contextual information—namely, in formation that surrounds the focal object. Asians are thus described as holistic or field dependent in cognitive style.

people engaging in North American cultures

As a whole, studies suggest that different cultures foster quite different modes of cognitive processing. In particular, people engaging in North American cultures (North Americans, in short) are assumed to be relatively more attuned to a focal object and less sensitive to context. North Americans are thus described as analytic or field independent in cognitive style.

RFT, Ji et al. (2000)

Ji et al. (2000):

Participants viewed a tilted frame with a rotating line at the center.

The participants’ task was to rotate the line so that it was aligned to the direction of gravity) while ignoring the frame.

Americans were more accurate than Chinese in aligning the line (hence indicating a superior ability to ignore contextual information).

This is important because the RFT has no obvious social elements, where as other tasks require incorporating contextual information.

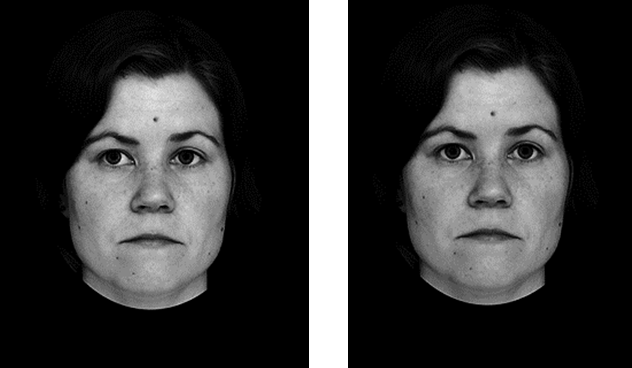

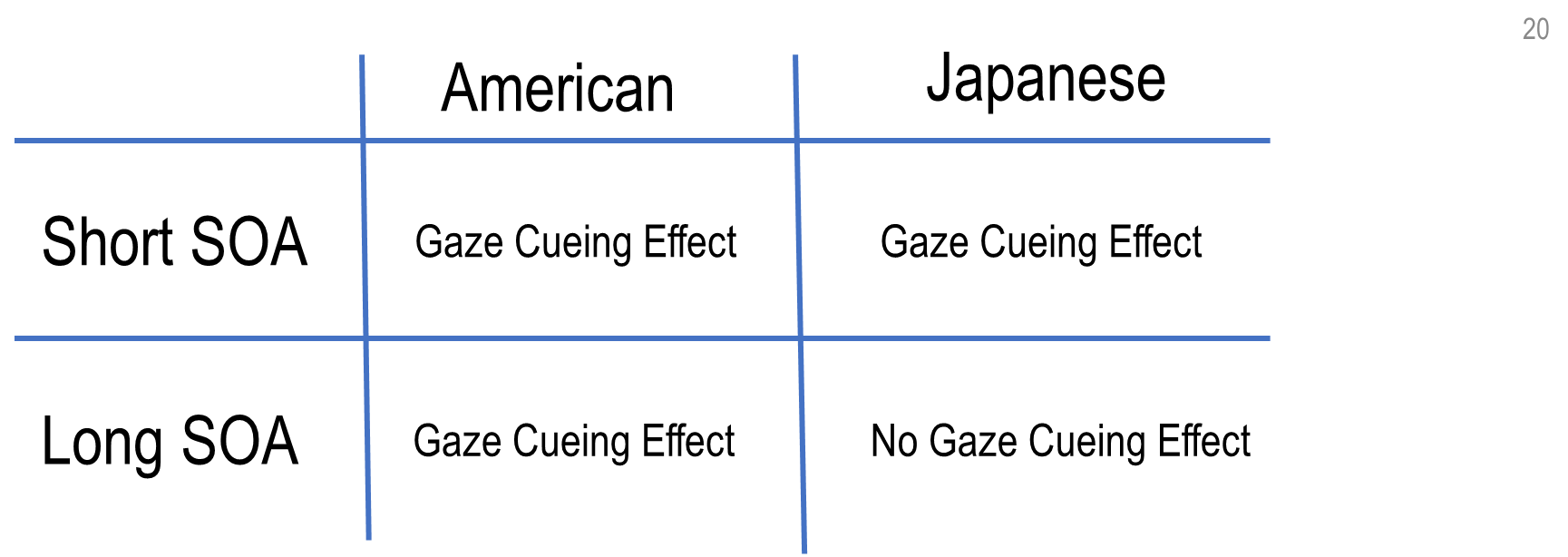

The present research- the FLT

There is substantial cognitive difference across cultures.

This difference can be demonstrated with tasks that are obviously social and minimally social.

Limitations hamper the development of theory on cultural variation in cognitive competences and to address these, the research has developed a test called the framed-line test (FLT).

The FLT assesses the ability to incorporate and to ignore contextual information within a single, nonsocial domain.

The FLT can be made in reference to an objective standard of performance.

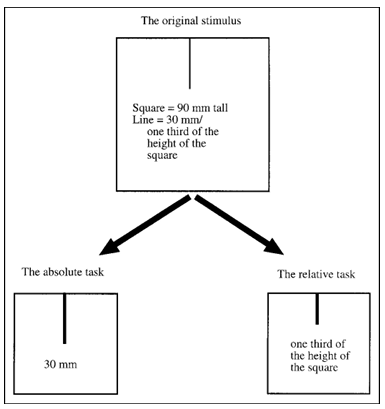

On each trial, participants are presented with a square frame, within it is a vertical line. The participants are then shown another square frame of the same or different size and asked to draw a line that is identical to the first line in either absolute length (absolute task) or proportion to the height of the surrounding frame (relative task).

In the absolute task, the participants have to ignore both the first frame (when assessing the length of the line) and the second frame (when reproducing the line).

North Americans should perform this better than Asians.

In the relative task, the participants have to incorporate the height information of the surrounding frame in both encoding and reproducing the line.

Asians should perform this task better than North Americans.

limitations that have hampered the further development of theory on cultural variation in cognitive competences.

First, with the important exception of the work by Ji et al. (2000), virtually no studies have evaluated performance against any objective criterion. This makes it difficult to draw conclusions on the normative status of the cognitive biases suggested.

Second, participants were not instructed to use contextual information, and therefore it is uncertain whether the cross-cultural differences were due to Asians’ greater propensity to attend to the con text, their greater competence to incorporate information in the con text, or both.

Third, it is not clear whether Asians’ greater ability to in corporate context extends to nonsocial tasks.

Fourth, in all the existent studies, very different domains, such as line alignment and social perception, were used in defining the two theoretical types of tasks. This makes it impossible to draw any meaningful comparison between performance in an absolute task and a relative task.

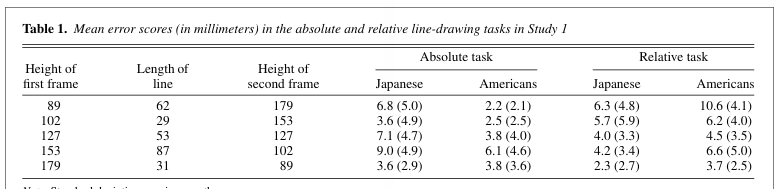

Study 1: the FLT in Japan and the US: methods

participants:

Twenty undergraduates at Kyoto University, in Kyoto, Japan (8 males and 12 females), and 20 undergraduates at the University of Chicago (9 males and 11 females) volunteered to participate in the study. All the Japanese undergraduates were native Japanese, and all the Ameri can undergraduates were of European descent.

materials and procedure:

Upon arrival in a lab, participants were told that they would per form simple cognitive tasks. They were given both the absolute task and the relative task in a counterbalanced order, receiving specific in structions for each task right before they performed it. In both tasks, on each trial they were shown a square frame, within which a vertical line was printed. The line was extended downward from the center of the upper edge of the square (see Fig. 1). The participants were then moved to a different table placed in the opposite corner of the lab (so as to ensure that iconic memory played no role) and shown a second square frame that was either larger than, smaller than, or the same size as the first frame. The task was to draw a line in the second frame. In the absolute task, the participants were instructed to draw a line that was the same absolute length as the line in the first frame. In the rela tive task, the participants were instructed to draw a line whose propor tion to the size of the second frame was the same as the proportion of the first line to the size of the first frame. We took care to ensure that the participants understood the tasks by using concrete examples, such as the ones given in Figure 1. The stimuli were prepared such that there were five different combinations of the relative sizes of the two frames and the line in the first frame.

Fig. 1. Example of the framed-line test (FLT) used in these studies. Participants were shown a square frame with a vertical line, and asked to draw a line in a new square of the same or different size. The line was to be drawn so that it was identical to the first line in absolute length (absolute task) or so that the proportion between the length of the line and the height of its frame was identical to the proportion be tween the line and frame in the original stimulus (relative task).

In two combinations the first frame was smaller than the second, and in two other combinations the first frame was larger than the second. Furthermore, in half of these cases, the first line was longer than one half the height of the first square, and in the remaining half, the first line was shorter than half the height of the first square. Finally, in the fifth combination, the first and the second frames were identical in size. This last case is of interest because the correct response would be identical in the relative and the absolute tasks. The five combinations were presented in a random order. The same stimuli were used in the relative and absolute tasks.

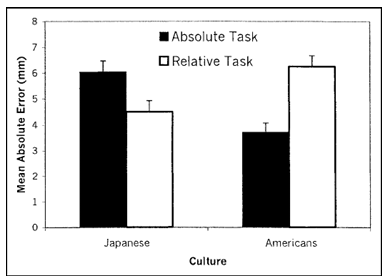

Study 1: the FLT in Japan and the US: Results and discussion

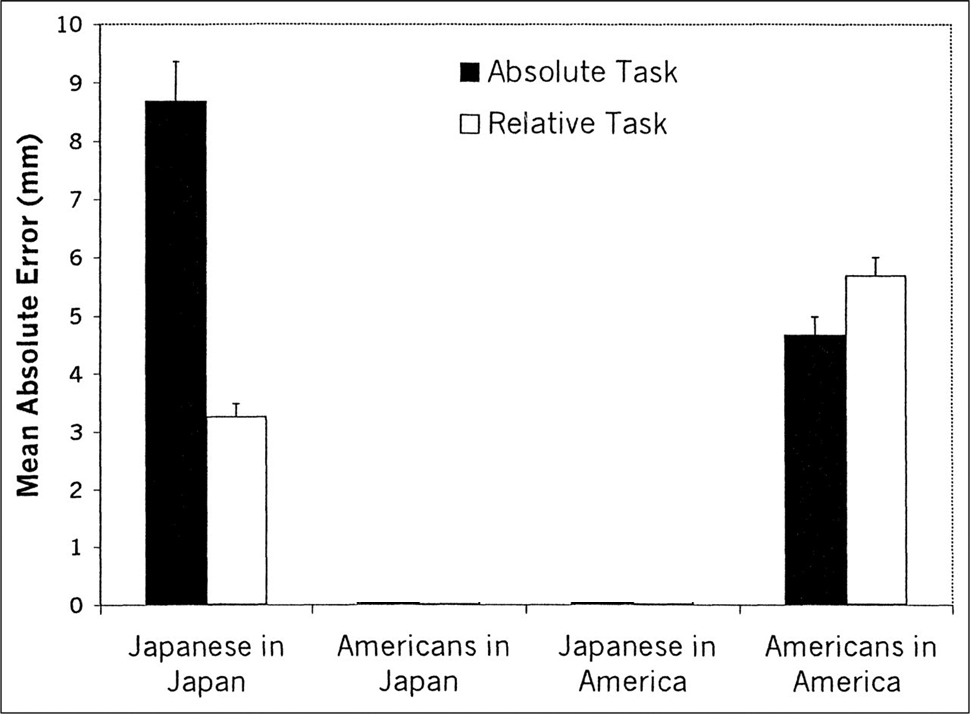

Overestimation and underestimation occurred to a nearly As predicted, the interaction between culture and task proved significant. The pertinent means are plotted in Figure 2. As predicted, Japanese performed the relative task significantly more accurately than the absolute task. In contrast, Americans performed the absolute task more accurately than the relative task. Moreover, Americans performed the absolute task significantly better than Japanese, in the relative task, and the reverse was true for performance. The relative ease of the two tasks varied across the five stimulus combinations, as indicated by a significant main effect of version and a significant interaction between version and task, and However, the three-way interaction involving culture, task, and version was negligible. Thus, the pattern in Figure 2 emerged over all the five combinations. The same pattern emerged even when the two frames were identical in size, and the correct length was identical in the two tasks. Specifically, for this stimulus combination, Japanese performed the relative task significantly better than the absolute task, although the difference in performance was considerably attenuated for Americans.

Fig. 2. Results from Study 1: Japanese and American participants’ mean error (in mms) in the two line-drawing tasks of the framed-line test. The error bars represent standard errors.

Study 2: variability and malleability of FLT performance:

In Study 2, we sought to replicate Study 1 and to extend it by testing both Americans and Japanese in both Japan and the United States. This effort was motivated by a concern with the variability and malleability of cross-cultural variations.

If the cross-cultural difference we observed is uniform and stable and traitlike over time, then the cross-cultural variation should be a function of the cultural origins: Americans (or Japanese) should show a prototypically American (or Japanese) pattern more or less uniformly regardless of where they are tested.

If, however, the cognitive abilities at issue are variable and malleable, there ought to be considerable variation as a function of both the cultural origins of participants and the specific location in which they are tested. Specifically, participants in a foreign culture should show a pattern of cognitive biases that resembles the pattern in the host culture.

Study 2: variability and malleability of FLT performance: methods

participants-

Four groups of individuals (total N 111) volunteered for the study. The Japanese in Japan were 32 undergraduates (20 males and 12 females) at Kyoto University. They were tested by a Japanese experimenter, and instructions were given in Japanese. The Americans in Japan were 18 ex change students (8 males and 10 females) who were temporarily staying at the Kansai Institute for Foreign Languages. They had stayed in Japan for 4 months at most, and their Japanese proficiency was quite limited. They were tested by a Japanese experimenter, and their instructions were given in English. The Americans in the United States were 40 undergraduates (21 males and 19 females) at the University of Chicago, and the Japanese in the US were 21 Japanese undergraduates (13 males and 8 females) who were temporarily studying at the University of Chicago. These Japanese had stayed at the university for a varying length of time, from 2 months up to 4 years. The Americans and the Japanese in the United States were both tested by an American experimenter, and instructions were given in English.

materials and procedure-

Six different combinations of the relative sizes of the two frames and the line in the first frame were prepared. They were similar to the combinations used in Study 1, except that some of the ratios of the size of the two frames were somewhat changed and the pattern with the two frames of the identical size was run in two variations. The participants were tested individually using the same procedure as in Study 1.

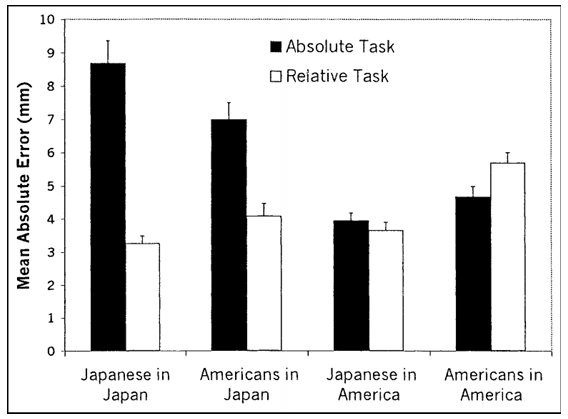

Study 2: variability and malleability of FLT performance: results

As in Study 1, there was no systematic tendency for over- or under estimation in any stimulus combinations.

Preliminary analysis showed no significant effects involving the gender of participants. Although past research tended to show females as more context sensitive than males, this effect appears to be less robust than the cultural difference.

The size of error varied systematically across the four groups of participants. Further, the size of error was larger for the absolute task than for the relative task.

However, the critical interaction between task and cultural origin proved to be highly significant. More over, there was a highly reliable interaction between task and testing location.

Japanese participants in Japan were more accurate in the relative task than in the absolute task. In contrast, Americans in the US were significantly more accurate in the absolute task.

The remaining two groups of participants showed an effect that strongly resembled the effect of the host culture. Examined from a different angle, performance in the relative task was significantly better for Japanese in Japan than for Americans in the United States but performance in the absolute task was better for Americans in the United States than for Japanese in Japan. In both cases, the data in the remaining two groups fell in between. It is noteworthy that essentially the same pattern was observed across the six combinations of stimuli. In particular, as in Study 1, the same cross-cultural difference in error pattern was observed even when the two frames were equal in size

Fig. 3. Results from Study 2: Mean error scores (in mms) in the two line-drawing tasks of the framed-line test. Results are shown separately for Japanese and Americans in the two cultural locations, Japan and the United States. The error bars represent standard errors.

Study 2: variability and malleability of FLT performance: General discussion

Future research should clarify the social origins of the nonsocial cognitive and attentional skills and processes involved in the FLT and the contribution of these processes to judgments and inferences about social objects. We found the same cross-cultural variation in error pattern even when the two frames were identical. This finding contradicts the notion that Asians (or Americans) are predisposed to perform the relative (or the absolute) task even when instructed to do otherwise. If our participants had such predispositions, errors should have been minimal when the two frames were identical because, under these conditions, the correct answers in the two tasks converge.

We suggest that errors were due, in part, to difficulty in accurately encoding the central line. That is, whereas Japanese may have had difficulty releasing attention from the frame and refocusing it on the line in the absolute task, Americans may have had difficulty releasing attention from the central line and shifting it to the frame in the relative task.

Study 2: variability and malleability of FLT performance: limitations

Study 2 should be interpreted with caution.

One interpretation is that the effect of test location was caused by immersion in a new culture, so cognitive and attentional tendencies are modified through the new demands of living in a new host culture. Such a modification could be permanent or relatively temporary and reversible. These possibilities have different implications for when people return to their home country.

However, other interpretations are possible. Because we could not have as much experimental control as preferred, like depending entirely on convenience samples. We acknowledge 3 difficulties in interpretation:

First, the average length of stay in the host culture was different between the Americans in Japan and Japanese in the US. A more balanced sampling would have been desirable.

Second, the language used for instructions was also chosen for convenience. In the US both Americans and Japanese were tested in English, but in Japan they were tested in their native languages. This might have had an unknown influence on the results as language can prime the associated culture.

Third, both the Japanese participants in the US and the American participants in Japan voluntarily moved to the other culture. The possibility of selection bias is equally viable. Only people with psychological affinities to another culture may find themselves living in this other culture.

Study 2: variability and malleability of FLT performance: what would these results provide in the grand scheme of things?

Current work suggests that different cultures’ practices and beliefs encourage very divergent cognitive and attentional capacities involved in either incorporating or ignoring context while making a judgment about a focal object.

Future work may reveal sociocultural shaping of attention and perception. This would provide a basis for reconceptualizing human psychological processes as fully embedded in and constituted by the shared practices, values, and beliefs of culture.

Indeed, the thesis of the New Look will be instrumental in breaking the shell of traditional psychological discipline and broadening it to include society, culture, and history.