Neuroscience; Week 3; child and adolescent mental health

1/65

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

66 Terms

problems with addressing children and adolescent mental health

considering what is appropriate for a particular age

difficulty in children being able to communicate and describe their problems

cultural norms

quick developmental trajectories

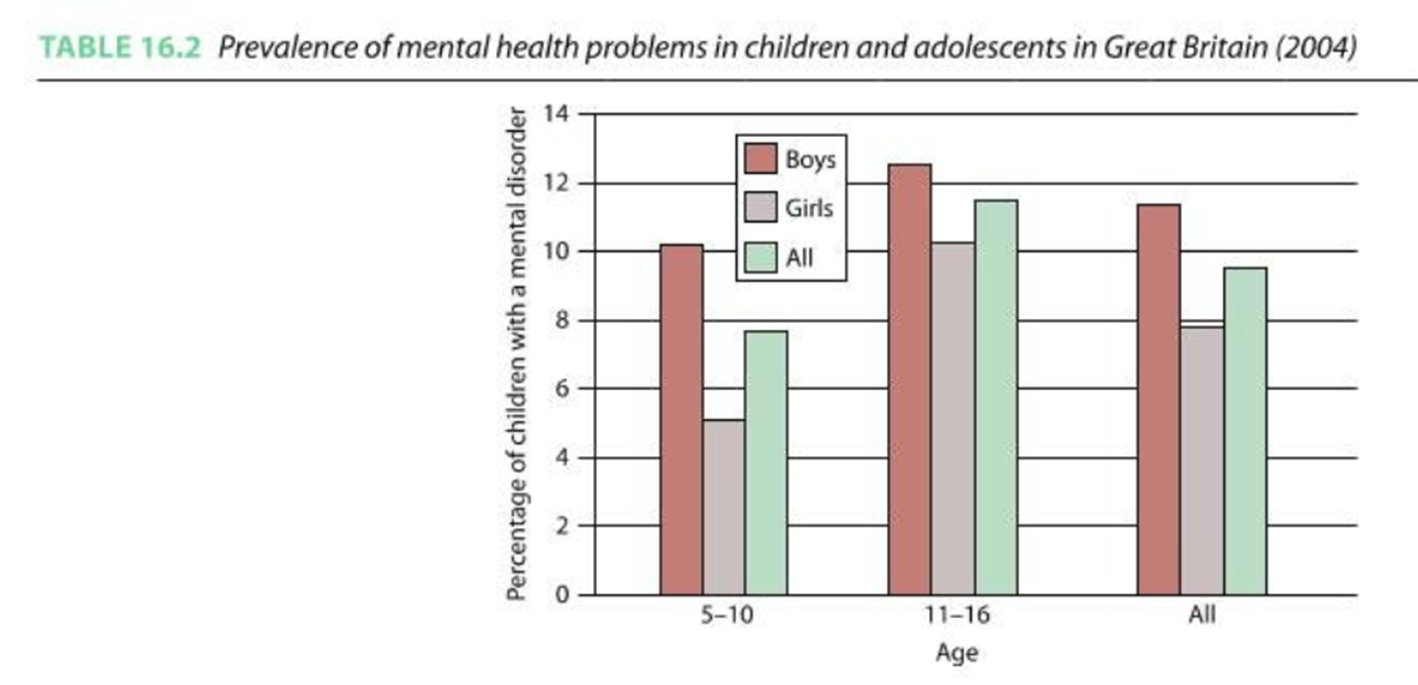

mental health problems for adolescence: incidence

more recent studies suggest the incidence is as high as 20%

internal/ external disorders

externalising disorders: disorders based on outward-directed behaviour problems such as aggressiveness, hyperactivity, non-compliance or impulsiveness.

internalising disorders: disorders represented by more inward-looking and withdrawn behaviours, and may represent the experience of depression, anxiety and active attempts to socially withdraw.

childhood anxiety

separation anxiety (specific to childhood)

very anxious from being away from attachment figures, or worries of potential harm, need to go on for 4 weeks to get a diagnosis as a child but 6 months for adults though this is rarer

OCD (similar to adult apart from children can get compulsions without obsessions (e.g. intrusive thoughts)

can lead to hoarding behaviour

generalised anxiety disorders

chronic worrying about potential problems and threats, pathological worrying

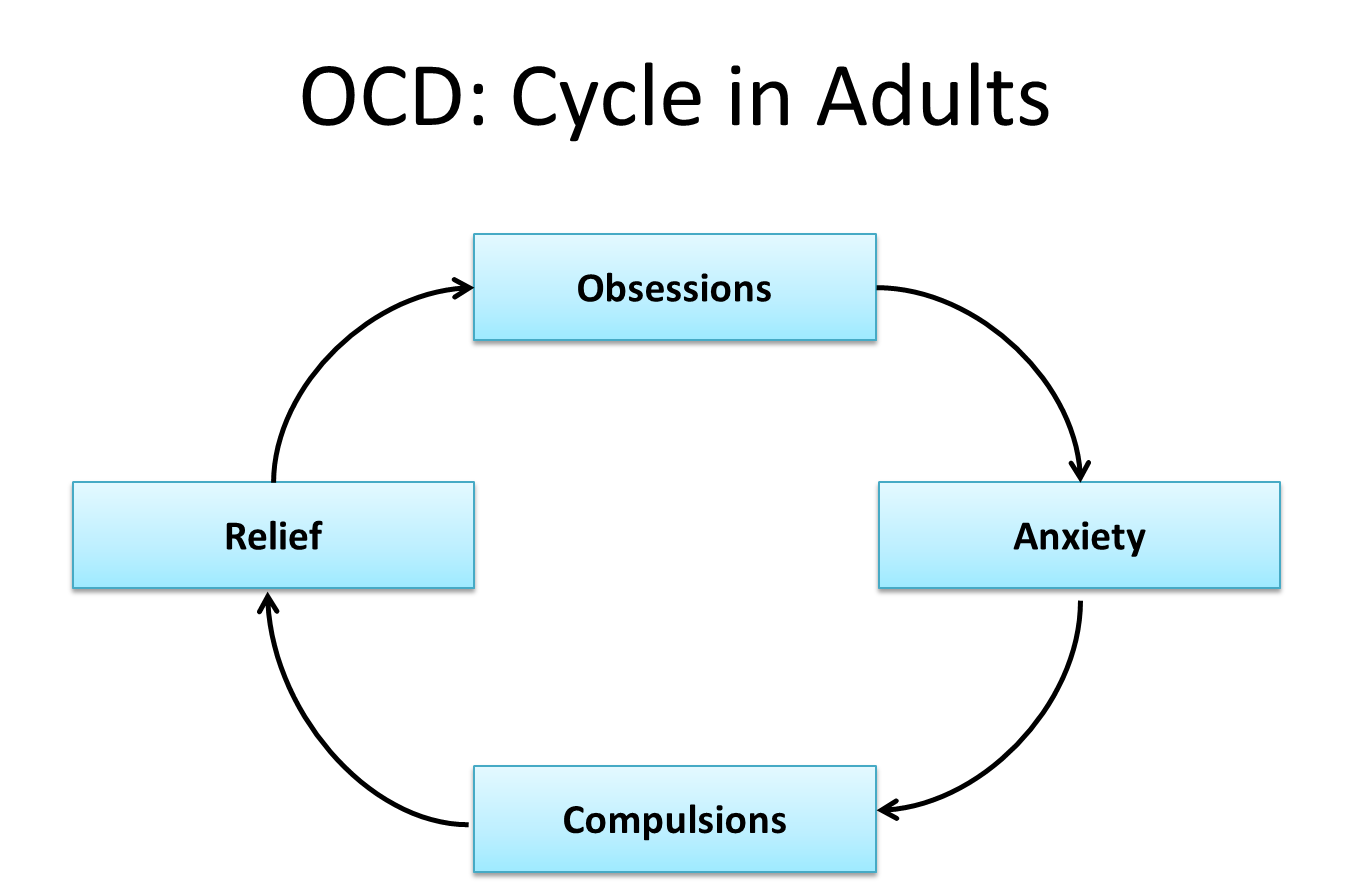

OCD: cycle in adults

Obsessions: intrusive and recurring thoughts that the individual finds disturbing and uncontrollable- often is about causing harm to oneself or a loved one.

Obsessive thoughts can also take the form of indecision, and may lead to sufferers developing repetitive behaviour patterns such as compulsive checking.

Compulsions: repetitive or ritualised behaviour that individuals feels driven to perform to prevent some negative outcome.

They act to reduce stress and anxiety caused by the sufferer’s obsessive fears.

In most cases compulsions are clearly excessive and are recognised as so by the sufferer

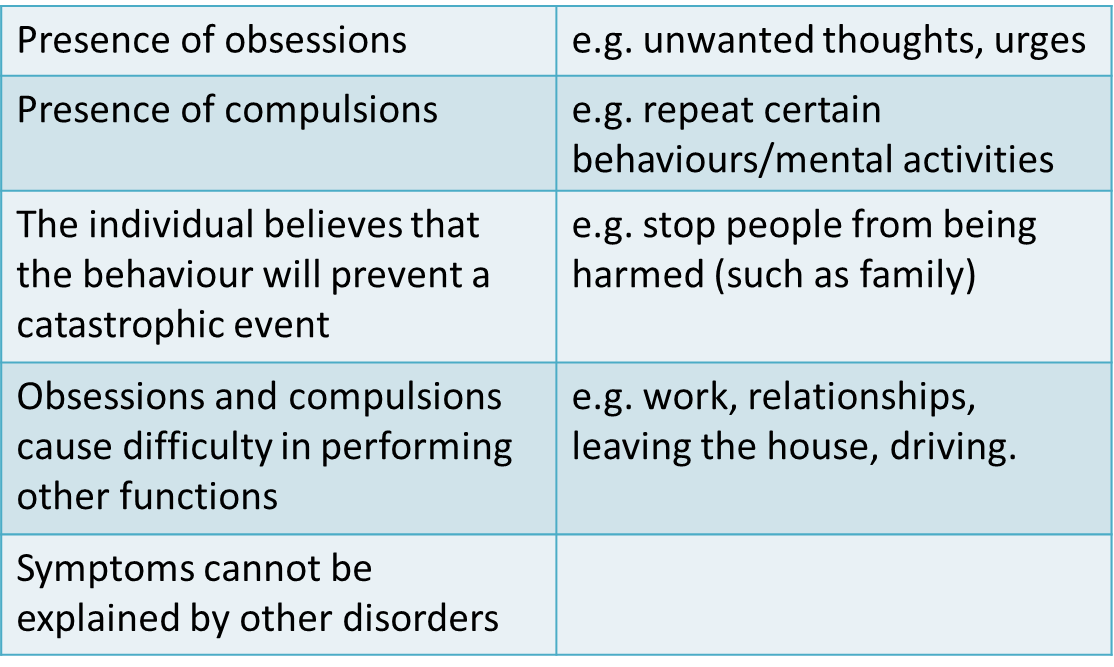

OCD: Types and Diagnosis

Types of OCD:

Checking

Contamination

Symmetry and ordering

Ruminations/intrusive thoughts

OCD: Diagnosis

Diagnosis is dependent on the obsessions and compulsions causing marked distressed, being time consuming or significantly interfering with the persons normal daily living.

Childhood anxiety developmental trajectory

4-7 years old separation from parents and fear of imaginary creatures

11-13 years old social threats

8 year olds have double the worries of 5 year olds

1% UK, some US studies 11%

Anxiety- heritability and origin of disorder

Moderate heritability – 54%

Trauma

Modelling and exposure to information

parenting style; if the parent is overly involved with the child or not involved enough, either could lead to anxiety

COVID increased the rate of incidence of anxiety and has become a large area of research for psychologists

Childhood and adolescent depression- recognition of disorder

Difficult to recognise in young children:

‘Clingy’ behaviour, school refusal, exaggerated fears

Somatic complaints: stomach aches and headaches, ways to physically describe their mental and psychological problems with their limited understanding and limited vocabulary

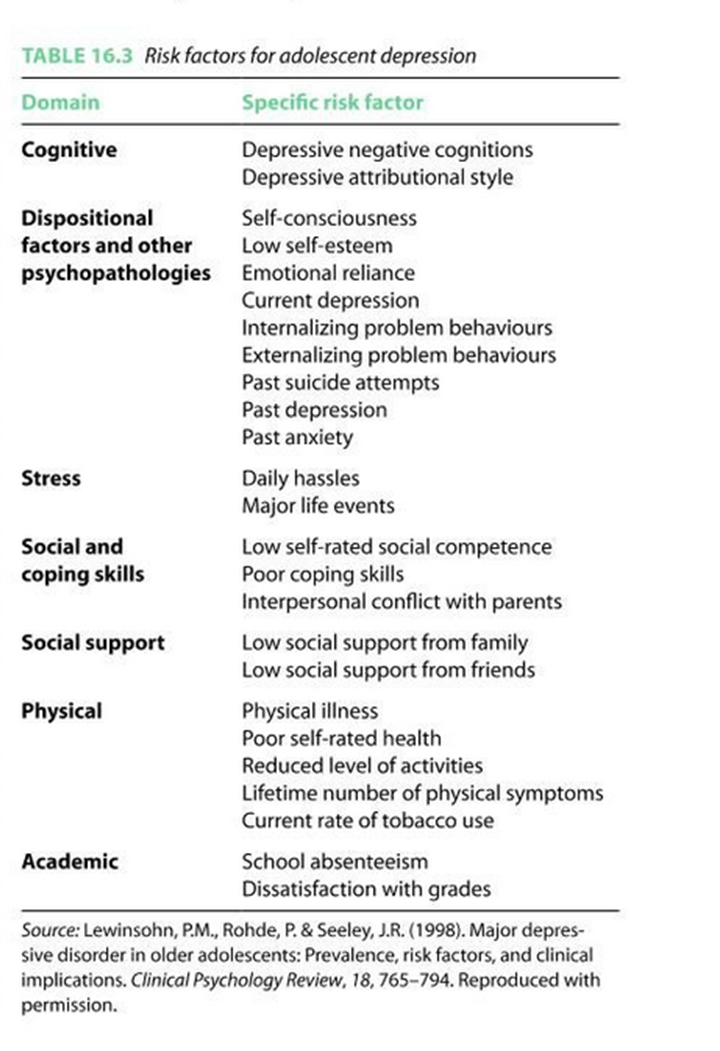

Causes of childhood and adolescent depression

Range of heritabilitys reported. Some studies find low in childhood increasing in adolescence.

In younger children abuse or neglect are risk factors, could be the case that depression is environmental in childhood, regarding amygdala interaction with the environment

what increases the risk of depression?

Genes

Psychological

transmit low mood and attributions, may not be able to respond to child’s emotions, provide fewer enrichment activities

ADHD- two different forms commonly recognised

ADHD predominantly inattentive presentation

Fails to pay close attention to details, has difficulty sustaining attention, does not appear to listen, struggles to follow through on instructions, has difficulty with organisation, avoids or dislikes tasks requiring a lot of thinking, loses things, is easily distracted

ADHD predominantly hyperactive/impulsive presentation

squirms and fidgets, can’t stay seated, can’t play/ works quietly, blurts out answers, is unable to wait for his turn, intrudes/ interrupts others, talks excessively

Combined presentation

both criteria for the previous two

What problems are there with drug treatments in childhood/ adolescence compared to adulthood?

brain’s are still developing

potential influences of hormones during puberty? how do we know drug treatments are effective if mood is unstable due to teen hormones

an ethical consideration: can the children give informed consent?

Study with an anxious mouse (Science, 29 Oct 2004)

mouse anxiety test: open field test, put the mouse in a new environment and watch how much they move, the more the mouse walks about the less nervous the mouse is

if they’re scared they’ll probably freeze/ hide in the corner

given saline as a young mouse does a lot more moving about, mouse injected with prozac when young moved around a lot less, suggesting they were more nervous/ anxious

it could be argued that they didn’t move BECAUSE they were chilled out, but generally agreed to be the former

Treatment of childhood and adolescent psychological problems

drug treatments - similar to adult

family interventions:

Systemic family therapy – therapists helps family with their communication and organisations

Parent management training – not rewarding antisocial behaviours

Functional family therapy – strengthens relationships

•CBT

•Play therapy

Disruptive behaviour disorders (2 types)- externalising disorders

Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD)

Conduct disorder (CD)

CD – before 10 years of age (childhood), after 10 year of age -adolescence.

Formerly known as externalising disorders

Anti-social personality disorder

happens if the disruptive behaviour disorders continue after the age of 18, this is the identification for it

Callous and unemotional (CU) traits

Distinguished by a persistent pattern of behaviour that reflects a disregard for others, and also a lack of empathy and generally deficient affect.

problems in emotional and behavioural regulation that distinguish them from other antisocial youth and show similarity to adult psychopathy.

Antisocial youth with CU traits are often less sensitive to punishment cues, particularly when they are already keen for a reward.

CU traits are positively related to intellectual skills in the verbal realm.

Common mental health disorders in childhood

Mental health disorders (MHD) are very common in childhood and include

emotional-obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

anxiety,

depression,

oppositional defiance disorder (ODD),

conduct disorder (CD),

ADHD

developmental (speech/language delay, intellectual disability) disorders

pervasive (autistic spectrum) disorders.

Emotional and behavioural problems (EBP) or disorders (EBD) can also be classified as either “internalizing” (emotional disorders such as depression and anxiety) or “externalizing” (disruptive behaviours such as ADHD and CD).

What is normal for very young children and what is not?

What is seen as norm:

allow-intensity naughty

defiant and impulsive behaviour from time to time

losing one’s temper

destruction of property

deceitfulness/stealing in preschool children

what isn’t:

extremely challenging behaviours outside the norm for the age and level of development,

such as unpredictable, prolonged, and destructive tantrums

severe outbursts of temper loss are recognized as behaviour disorders.

More than 80% of pre-schoolers have mild tantrums but less than 10% have daily tantrums, regarded as normative misbehaviours. Challenging behaviours and emotional difficulties are likely to be recognized as “problems” rather than “disorders” during the first 2 years of life.

What issues occur more in later childhood?

Emotional problems, such as

anxiety,

depression

post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

They are difficult to recognise early as many children have not developed appropriate vocabulary, and are unable to express emotions intelligibly.

Many find it difficult to distinguish between developmentally normal emotions (e.g., fears, crying) from severe emotional distresses regarded as disorders.

Identification and management of MHP

Identification and management of mental health problems in primary care settings such as routine Paediatric clinic or Family Medicine/General Practitioner surgery are cost-effective

their several desirable characteristics make it acceptable to children and young people (e.g., no stigma, in local setting, and familiar providers).

models to improve the delivery of mental health services in these settings include coordination with external specialists, joint consultations, improved Mental Health training and more integrated on-site intervention with specialist collaboration.

Challenging behaviours - definitions

Any abnormal pattern of behaviour above the expected norm for age and level of development

“Culturally abnormal behaviour of such an intensity, frequency or duration that the physical safety of the person or others is likely in serious jeopardy or behaviour which is likely to seriously limit use of ordinary community facilities”.

These behaviours can impede learning, restrict access to normal activities and opportunities, and require considerable manpower and financial resources to manage effectively.

what can challenging behaviour indicate?

Many instances it can be an ineffective coping strategies to control what is going on.

Young people with disabilities may use challenging behaviour for sensory stimulation, gaining attention of carers, avoiding demands or to express limited communication skills.

People who have a diverse range of neurodevelopmental disorders are more likely to develop challenging behaviours.

what may increase challenging behaviour?

Some environmental factors increase the risk of challenging behaviour, including places offering limited opportunities for making choices, social interaction or meaningful occupation.

Other adverse environments are limited sensory input or excessive noise, unresponsive/unpredictable carers, predisposition to neglect and abuse, and where physical health needs are not promptly identified.

For example, the rates of challenging behaviour in teens/ early 20s is 30%-40% in hospital settings, compared to 5% to 15% among children attending schools for those with severe LD.

explain a common challenging behaviour

Aggression

it is a frequent indication for referral to child and adolescent Psychiatrists.

It commonly begins in childhood,

more than 58% of preschool children demonstrate some aggressive behaviour

it has been linked to several risk factors, including

individual temperaments;

the effects of disturbed family dynamics;

poor parenting practices;

exposure to violence

the influence of attachment disorders.

No single factor explains the development of aggressive behaviour.

Aggression is commonly diagnosed in association with mental health problems including ADHD, bipolar disorder, or dyslexia

Disruptive behaviour problems

DBP include:

ADHD

oppositional defiant disorder (ODD)

and conduct disorder (CD). .

They constitute the commonest EBPs among CYP.

Recent evidence suggests that DBPs should be regarded as a multidimensional phenotype rather than comprising distinct subgroups

ADHD

the commonest neuro-behavioural disorder in children and adolescents,

prevalence 5%-12% in developed countries.

characterized by levels of hyperactivity, impulsivity and inattention that are disproportionately excessive for the child’s age and development.

The ICD-10 uses the term “hyperkinetic disorder”, which is equivalent to severe ADHD.

Conduct disorder

refers to severe behaviour problems

characterized by repetitive and persistent manifestations of serious aggressive behaviours against people, animals or property

such as being defiant, destructive, physically cruel, deceitful, excessive bullying, fire-setting, forced sexual activity and frequent school truancy.

They have trouble understanding how other people think (callous-unemotional).

They may falsely misinterpret the intentions of other people as being mean.

They may have immature language skills, lack appropriate social skills to establish friendships, which aggravates their feelings of sadness, frustration and anger

DSM-5 definition of conduct disorder

Repetitive behaviour where others’ basic rights or major age-appropriate societal norms are violated,

at least 3/15 in 12 mo, 1 in 6 mo

Aggression to people and animals:

(1) bullies/threatens others;

(2) initiates physical fights

(3) has used a weapon that can cause serious physical harm;

(4) has been physically cruel to people;

(5) has been physically cruel to animals;

(6) has stolen while confronting a victim like mugging or armed robbery;

(7) has forces someone into sexual activity

destruction of property:

(8) has deliberately engaged in fire setting to cause serious damage

(9) has deliberately destroyed others’ property (not by fire)

deceitfulness or theft:

(10) has broken into someone else’s property

(11) often lies to obtain favours to avoid obligations (i.e. cons others);

(12) has stolen items of nontrivial value without confronting a victim (e.g. shoplifting)

serious violations of rules:

(13) stays out at night despite parental prohibitions before age 13;

(14) has run away from home overnight at least twice, or once without returning for a long period;

(15) is often truant from school, beginning before 13yrs

If the individual is age 18 yr or older, criteria are not met for antisocial personality disorder

Specify whether: Childhood-onset type (prior to age 10 yr); Adolescent-onset type

Specify if: With limited prosocial emotions: Lack of remorse or guilt; Callous-lack of empathy; Unconcerned about performance or Shallow or deficient affect

DSM-5 definition of oppositional defiant disorder

Angry/irritable mood, defiant behaviour, or vindictiveness lasting at least 6 mo

at least 4/8 symptoms exhibited during interaction not with a sibling

Angry/ irritable mood:

(1) often loses temper

(2) often angry and resentful

argumentative/ defiant behaviour:

(4) often argues with authority figures or, for adolescents, with adults;

(5) often actively defies to comply with authority figures/rules;

(6) deliberately annoys others;

(7) often blames others for their mistakes/behaviour

Vindictiveness:

(8) Has been spiteful at least twice within 6 mo

Note: the behaviour should occur at least once per week for at least 6 mo

The disturbance in behaviour is associated with distress in the individual or others in their immediate social context (e.g., family, peers),

The behaviours do not occur exclusively during the course of a psychotic, substance use, depressive, or bipolar disorder

ICD-10 ODD

It also requires the presence of 3 symptoms from the list of 15, and duration of at least 6 mo.

There are four divisions of conduct disorder: Socialised conduct disorder, unsocialised conduct disorder, conduct disorders confined to the family context and oppositional defiant disorder

why are children and young people referred for psychological and psychiatric treatment?

CD is the commonest reason for CYP referral for psychiatric treatment.

50% of all CYP with a MHD have a CD.

About 30%-75% of children with CD also have ADHD and 50% meet criteria for 1+ other disorders like Anxiety, PTSD, Substance abuse, ADHD, learning problems.

Majority of boys’ onset of CD is before 10 years, while girls present mainly 14-16 years.

Most CYP with CD grow out of it, but a minority develop antisocial personality disorder as adults.

ODD is the mildest and commonest of the DBPs

prevalence estimates of 6%-9% for pre-schoolers; boys outnumbering girls by at least 2:1

Emotional problems in later childhood

panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), separation anxiety, social phobia, specific phobias, OCD and depression.

Anxiety is a disorder when it is disproportionately excessive in severity in comparison to the circumstances, leading to disruption of daily routines.

Panic disorder is characterized by panic attacks untriggered by external stimuli.

GAD is characterized by generalized worry across multiple life domains.

Separation anxiety disorder is characterized by fear of actual/anticipated separation from a caregiver.

Social anxiety disorder is characterized by fear of social situations where peers may negatively evaluate the person.

common physical and mental manifestations of anxiety disorders

Physical symptoms such as increased heart rate, shortness of breath, sweating, trembling, chest pain, abdominal discomfort and nausea.

Other symptoms include worries about things before they happen, constant concerns about family/school/friends, repetitive, unwanted thoughts (obsessions) or actions (compulsions), fears of embarrassment or making mistakes, low self-esteem and lack of self-confidence.

Depression

Often in children under stress, experiencing loss, or having attentional, learning, conduct or anxiety disorders.

Symptoms often mimic other physical and neurodevelopmental problems, including

decreased pleasure in activities; or inability to enjoy favourite activities,

hopelessness,

persistent boredom;

low energy/ social isolation,

low self-esteem and guilt,

extreme sensitivity to rejection or failure,

increased irritability,

difficulty with relationships,

frequent complaints of physical illnesses such as headaches,

poor performance and concentration in school,

a major change in eating and/or sleeping patterns,

weight loss/gain,

efforts to run away from home,

expressions of suicide or self-destructive behaviour.

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD)

a childhood disorder characterized by a pervasively irritable or angry mood

recently added to DSM-5.

The symptoms include frequent episodes of severe temper tantrums or aggression (more than 3 episodes a week) in combination with persistently negative mood between episodes, lasting for more than 12 mo in multiple settings, beginning after 6 years but before 10 years old.

Pervasive developmental disorders

the umbrella term for 5 disorders characterized by pervasive “abnormalities in reciprocal social interactions and communication, and by restricted, stereotyped, repetitive interests and activities”. These included:

autism,

asperger syndrome,

childhood disintegrative disorder (CDD),

pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS)

and Rett syndrome.

Autism and Asperger Syndrome are the most clinically diagnosed.

CDD describes children who had normal development for the first 2-3 years before an acute onset of regression and emergence of autistic symptoms.

PDD-NOS described individuals who have autistic symptoms, but do not meet the criteria for Autism or Asperger’s Syndrome, or describe atypical autism symptoms after 30 mo, and autistic individuals with other co-morbid disorders.

PDD in the DSM-5

This has been removed from DSM-5 and replaced with Autism Spectrum disorders (ASD).

ASD is diagnosed primarily from a multidisciplinary team, with minimal support from diagnostic instruments.

91-100% of children with PDD diagnoses from the DSM-IV retained their diagnosis under the ASD category using the new DSM-5,

but a systematic review found a slight decrease of ASD with DSM-5 instead

DSM-5 criteria for autism spectrum disorders

Persistent deficits in social communication, 3/3 of the following:

Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity,

Deficits in nonverbal communicative behaviours used for social interaction

Deficits in developing, maintaining, and understanding relationships

Restricted, repetitive patterns of activities, at least 2/4 of the following:

repetitive motor movements

Insistence on sameness, inflexible adherence to routines, or ritualized patterns

Highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in intensity

Hyper/hypo-reactivity to sensory input

Symptoms must be present in early developmental period (but may be masked by learned strategies)

Specify

accompanying intellectual impairment

accompanying language impairment

Associated with a known medical or genetic condition or environmental factor

current severity based on social communication impairments and restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour

Summary of common social communication enhancement strategies

Method→ description

augmentative and alternative communication →

Replaces speech and writing with aided symbols [e.g., Picture Exchange Communication System] and/or unaided symbols (e.g., manual gestures)

decreases maladaptive behaviour such as self-injury and tantrums,

promotes cognitive development and improves social communication

Activity schedules/ visual supports →

Using photographs, or written words as prompts to help complete a sequence of activities or behave appropriately in various settings

promotes/sustains social interaction

Computer-/ video-based instruction →

Use of computer technology or video recordings for teaching language skills, social skills, social understanding, and social problem solving

Summary of common behavioural modification strategies for management of childhood emotional and behavioural disorder

Method → description

ABA → Uses learning theory to build positive change in behaviour (e.g., social skills, and self-monitoring) and generalize these skills to situations

Discrete trial training → A one-to-one approach based on ABA to teach skills in small steps in a systematic fashion, documenting antecedent and consequence (e.g., reinforcement of praise/rewards) for desired behaviours

Functional communication training → ABA procedures with communicative functions of maladaptive behaviour to teach alternative responses

pivotal response treatment → A play-based, child-initiated behavioural treatment, designed to teach language, decrease disruptive behaviours, and increase social, and academic skills, building on a child’s interests

Time delay → It gradually decreases the use of prompts over time. It can be used with individuals regardless of cognitive level

Social (pragmatic) communication disorder

a new diagnosis under Communication Disorders in the Neurodevelopmental Disorders section of the DSM-5.

characterized by persistent difficulties with using verbal and nonverbal communication for social purposes, which can interfere with interpersonal relationships and academic achievement, in the absence of restricted and repetitive interests and behaviours.

SCD occur more in family members of individuals with autism

DSM-5 criteria for social (pragmatic) communication disorder:

Difficulties of communication as manifested by:

Deficits in using communication for social purposes, such as greeting, that is appropriate for social context

Inability to change communication to match context of the listener, i.e. talking differently to a child Vs an adult,

Difficulties following rules for conversation, such as taking turns in conversation

Difficulties understanding what is not explicitly stated and nonliteral meaning of language (e.g., humour, metaphors)

The onset of the symptoms is in the early developmental period (but deficits may become fully manifest only when social communication demands exceed capacities)

Pathological demand avoidance or Newson’s syndrome

first used in 2003 to describe some CYP with autistic symptoms who showed challenging behaviours.

characterized by exceptional demand avoidance, due to high anxiety levels when they feel that they are losing control.

Avoidance strategies can range from simple refusal, to becoming physically incapacitated (with an explanation such as “my legs don’t work”) or selectively mute.

If they feel threatened to comply, they may become aggressive, intended to shock.

They tend to resort to “socially manipulative” behaviours. The lack of concern for their behaviour draws parallels to conduct problems (CP) and callous-unemotional traits (CUT),

reward-based techniques don’t work.

PDA is not in the DSM-5 nor the ICD-10.

demand avoidance: ASD (autism spectrum disorder) Vs PDA (pathological demand avoidance)

People with PDA tend to have good social communication and interaction skills (unlike ASD), and use this to their advantage. They often have highly developed social mimicry.

People with PDA know how to “push people’s buttons”, suggesting a level of social insight compared to Autism.

On the other hand, children with PDA exhibit higher levels of emotional symptoms. They experience excessive mood swings and impulsivity.

Prevalence of ASD in boys is 4 times higher than girls, the risk of developing PDA appears the same for both.

PREVALENCE AND RISK FACTORS OF BEHAVIOURAL AND EMOTIONAL DISORDERS IN CHILDHOOD

Accurate estimation of childhood EBPs is difficult due to subjective assessments and varying definitions. 10%-20% of CYP are affected annually by MHDs.

Low socioeconomic status are risk factors that increase the rate of MHDs.

A 2001 WHO report indicated the 6-mo prevalence rate for any MHD in CYP to be 20.9%, with disruptive behaviour disorders (DBD) at 10.3%, and Anxiety disorders at 13%.

5% of CYP suffer from Depression at any point, more among girls (54%).

A CAMH survey found prevalence of MHD among aged 5-16 years to be 6% for conduct problems, 4% for emotional problems (Depression or Anxiety) and 1.5% for Hyperkinetic disorders.

A survey in the US 2005-2011, indicated that 4.6% of CYP aged 3-17 years had a DBD, with prevalence twice as high among boys (6.2% vs 3.0%), Anxiety (4.7%), Depression (3.9%), and ASD (1.1%).

Reported prevalence rates for DMDD from 0.8%-3.3% with the highest rate in preschool children

AETIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS FOR CHILDREN’S BEHAVIOURAL AND EMOTIONAL DISORDERS, INCLUDING A DEVELOPMENTAL TAXONOMY THEORY

Studies identified genetic predisposition and adverse environmental factors; including perinatal, maternal, family, parenting, socio-economic and personal risk factors.

The genetic inheritability of EBDs in CYP: A study of 209 parents with their 331 biological offsprings found moderate inheritability between parental and offspring CD.

A developmental taxonomy theory (Patterson et al) may explain early onset and course of CPs. They described a cycle of non-contingent parental responses to prosocial and antisocial child behaviour which reinforces child behaviour problems. Parents’ engagement in “coercive cycles” lead to children learning the functional value of aversive behaviours for avoidance from unwanted interactions, leading to aversive behaviours from both to obtain social goals.

Summary of common risk factors for development of childhood emotional and behavioural disorder: maternal psychopathology (mental health status)

Low maternal education,

parents with depression,

antisocial behaviour,

smoking,

psychological distress,

alcohol problems,

an antisocial personality,

substance misuse or criminal activities,

teenage parental age,

marital conflict or violence,

previous abuse as a child and single (unmarried status)

Summary of common risk factors for development of childhood emotional and behavioural disorder: adverse perinatal

Maternal gestational moderate alcohol drinking, smoking and drug use, early labour onset, difficult pregnancies, premature birth, low birth weight, and infant breathing problems at birth

Summary of common risk factors for development of childhood emotional and behavioural disorder: poor child-parent relationships: examples

Poor parental supervision,

erratic harsh discipline,

parental disharmony,

rejection of the child,

low parental involvement in the child’s activities

Summary of common risk factors for development of childhood emotional and behavioural disorder: adverse family life

Dysfunctional families where domestic violence, poor parenting skills or substance abuse are a problem, lead to

increased parental conflict,

greater harsh, physical, and inconsistent discipline,

less responsiveness to children’s needs,

less supportive and involved parenting

Summary of common risk factors for development of childhood emotional and behavioural disorder: household tobacco exposure

Studies have shown a strong exposure–response association between second-hand smoke exposure and poor childhood mental health

Summary of common risk factors for development of childhood emotional and behavioural disorder: poverty and adverse socio-economic environment

Poverty signs including homelessness, low SES, overcrowding, social isolation, and exposure to toxic air, and/or pesticides or early childhood malnutrition lead to poor mental health development.

Chronic stressors associated with poverty such as single-parenthood, life stress, and financial worries, cumulatively compromise parental psychological functioning, leading to higher levels of distress, anxiety, anger, depressive symptoms and substance use in disadvantaged parents

Chronic stressors in children also lead to abnormal behaviour pattern of ‘reactive responding’ characterized by chronic vigilance, emotional reacting and sense of powerlessness

Summary of common risk factors for development of childhood emotional and behavioural disorder: early age onset and child’s temperament

early age of onset → Early starters are likely to experience more persistent and chronic trajectory of antisocial behaviours

Physically aggressive behaviour rarely starts after age 5

child’s temperament → Children with difficult to manage temperaments are more likely to develop disruptive behavioural disorders later in life

Chronic irritability, temperament and anxiety symptoms before 3 yrs are predictive of later childhood anxiety, depression, ODD and functional impairment

Summary of common risk factors for development of childhood emotional and behavioural disorder: developmental delay and intellectual disabilities

Up to 70% of preschool children with DBD are more than 4 times at risk of developmental delay than the general population

Children with intellectual disabilities are twice as likely to have behavioural disorders as normally developing children

Rate of challenging behaviour is 5% to 15% in schools for children with severe learning disabilities but is negligible in normal schools

Summary of common risk factors for development of childhood emotional and behavioural disorder: Child’s gender

Boys are much more likely than girls to suffer from several DBD while depression tends to predominantly affect more girls than boys

Unlike the male dominance in childhood ADHD and ASD, PDA tends to affect boys and girls equally

NEUROBIOLOGY OF CHILDHOOD BEHAVIOURAL AND EMOTIONAL DISORDERS: structural abnormalities, brain changes, HPA and testosterone

The most reported structural abnormalities were reduced grey matter volume (GMV) in the amygdala, frontal cortex, temporal lobes, and the anterior insula, which is involved in empathic concern for others.

Reduced GMV along the superior temporal sulcus found particularly in girls.

A decreased overall cortical thickness and grey matter density was reported.

fMRIs demonstrated less activation in the temporal cortex in violent, psychopathic offenders compared to non-aggressive offenders.

Reduced basal Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis activity in relation to childhood DBDs and exposure to abuse.

Perhaps prenatal testosterone exposure plays a role, explaining the higher prevalence in males, by increasing susceptibility to toxic perinatal environments such as exposure to maternal nicotine and alcohol in pregnancy.

Complications/ associations of childhood behavioural and emotional disorders:

CD is linked to failure to complete schooling, poor interpersonal relationships, and long-term unemployment.

EBPs in parents is linked to abusing offspring, which increases their risk of developing CD.

Sleep disturbances in early childhood is associated with increased prevalence of later Anxiety disorders and ODD.

Individuals on the adolescent-onset CP path often consume more illegal drugs, self-harm, and have increased risk of PTSD.

40%-50% of CYP with CD are at risk of developing antisocial personality disorder in adulthood.

Other complications include adverse mental and physical health outcomes, incarceration, substance abuse, homelessness and domestic abuse.

Assessment and diagnosis of childhood behavioural and emotional disorders:

Assessment requires detailed history taking and observation of behaviour for diagnosis. This includes:

medical, developmental, family, social, educational and emotional history.

Physical examination includes assessment of vision, hearing, dysmorphic features, motor skills and cognitive assessment.

There is no single diagnostic tool for EBDs. Diagnosis relies on subjective multi-source feedback from carers, teachers, peers, or professional through psychometric questionnaires/screening tools. Significant discrepancies between respondents is common and clinical diagnosis cannot rely on this alone.

There are screening tools to help identify individuals that require more in-depth clinical interventions. The commonest behaviour screening tools include the Behavioural and Emotional Screening System (ages 3-18 years), and the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA) (age 1.5 years-adulthood)

Management of behavioural and emotional disorders in children:

Treatment strategies depend on the symptoms, the family’s influences, wider socio-economic environment, the child’s developmental level and physical health. It requires multi-disciplinarian approaches that include Psychologists, Psychiatrists, Paediatricians, etc. Pharmacotherapy occurs only with other interventions.

Holistic management strategies include combinations of child- and family-focused strategies like CBT, parenting skills training and psychopharmacology.

Similar parenting strategies manage several dissimilar EBPs (e.g., sleeping problems, various emotional problems), which suggests a common maintaining mechanism; may be related to self-regulation skills like impulse control.

Studies confirm the effectiveness of these therapies for EBD management. A meta-analysis of 36 controlled trials demonstrated the largest effects for general externalizing symptoms and problems of non-compliance, and weakest for impulsivity and hyperactivity.

The treatment of CD among CYP with callous-unemotional traits is still at early stages of research.

Parental skills training:

Social-learning based parent training produces improvement in children with callous-unemotional traits or CD, increasing parent satisfaction.

These interventions are delivered in a group format, one 2-h session per week for 4-18 wk, to improve parenting skills to manage child behaviour. Parents learn to identify and define problem behaviours in new ways, and learn strategies to respond.

A meta-analysis of 24 studies confirmed that Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) demonstrated significantly larger effect sizes for reducing negative parent behaviours and negative child behaviours than all forms of Positive Parenting Programme.

A review confirmed the efficacy of group-based parenting interventions for alleviating child conduct problems, enhancing parental mental health and skills, at least short term.

Differentiated educational strategies:

“step-by-step” guidelines for teachers in the implementation of strategies increasing levels of engagement by children with EBD, including class-wide peer tutoring, Response to Intervention (RtI) and Positive Behavioural Interventions and Supports (PBIS).

Treatment and Education of Autistic and Related Communication Handicapped Children (TEACCH) is designed for the management of children with Autism and related communication disorders. It leads to improvements in motor skills and cognitive measures.

Specific guidelines for children with PDA show that educational support relies on highly individualized strategies that allows them to feel in control. They respond better to indirect and negotiative approaches. For example, “I wonder how we might…” rather than “Now let’s get on with your work”.

Child-focused psychological interventions - CBT and self-esteem building

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is the most widely used non-pharmacologic treatments for emotional disorders, like depression, and behavioural problems including ASD.

CBT integrates cognitive and behavioural learning principles to encourage desirable behaviour patterns. Research provides support for the effectiveness of cognitive–behavioural interventions among CYP with Anxiety and Depression. Child-focused CBT programme introduced at schools has shown that it produces significant improvement in disruptive behaviours.

Self-esteem building strategies can help children with EBDs, who experience failures at school and in interactions with others. They can be encouraged to identify and excel in their particular talents (such as sports) to help build their self-esteem.

Behavioural modification and social communication enhancement strategies

Behavioural techniques are designed to reduce problem behaviours and teach functional alternative strategies using the basic principles of behaviour change. Most interventions are based on Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA) which is grounded on behavioural learning theory.

Strategies help children acquire important social skills, such as how to have a conversation or play cooperatively with others, teach peer interaction skills and promote socially appropriate behaviours and communication.

Psychopharmacology of childhood behavioural and emotional disorders

Psychostimulants have been the medication for ADHD in for 60+ years. About 75%-80% of children with ADHD will benefit from psychostimulants.

Pharmacological treatments for ASD is common but no medication directly treat the social and language impairments in individuals with ASD. Antipsychotics (e.g., Risperidone) and SSRI treat mood and repetitive behaviour problems. Naltrexone significantly improves symptoms of self-injury, irritability, restlessness and hyperactivity in autistic children.

Medication use in preschool children with ASD and ADHD is largely controversial. Stimulant medications for ADHD are not licensed for pre-schoolers as there is limited research and parenting interventions have comparable effects.

Psychostimulants have a moderate-to-large effect on conduct problems, and aggression in youths with ADHD, while Atomoxetine has only a small effect.

Atypical antipsychotics can be used for OCD, Depression, aggression and mood instability.

Antidepressants are used to manage OCD, PTSD and Social Anxiety.