Neuroscience; Week 3; child and adolescent mental health

Problems:

considering what is appropriate for a particular age

difficulty in children being able to communicate and describe their problems

cultural norms

quick developmental trajectories

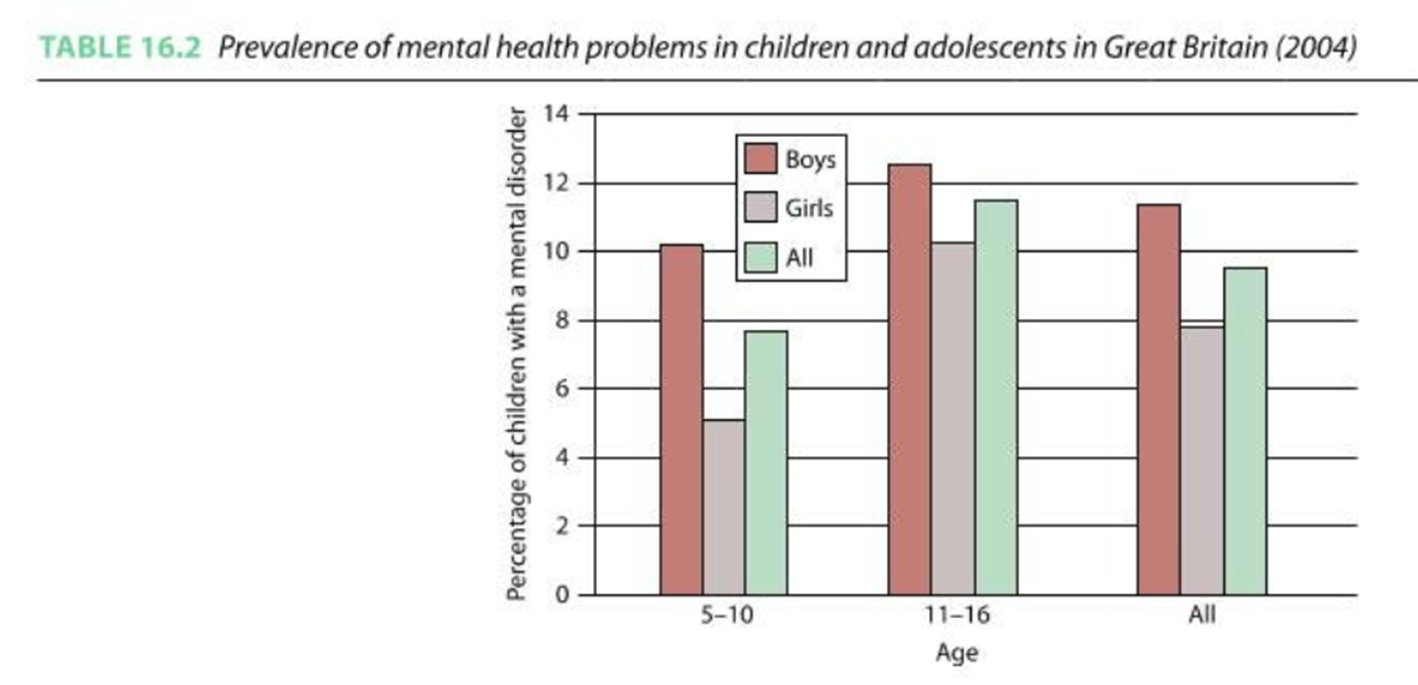

Incidence

more recent studies suggest the incidence is as high as 20%

internal/ external

externalising disorders: disorders based on outward-directed behaviour problems such as aggressiveness, hyperactivity, non-compliance or impulsiveness.

internalising disorders: disorders represented by more inward-looking and withdrawn behaviours, and may represent the experience of depression, anxiety and active attempts to socially withdraw.

Childhood anxiety

separation anxiety (specific to childhood)

very anxious from being away from attachment figures, worries of potential harm, or generally being far away from figures, need to go on for 4 weeks to get a diagnosis as a child but 6 months for adults though this is more rare at an older age

OCD (similar to adult apart from children can get compulsions without obsessions (e.g. intrusive thoughts)

can lead to hoarding behaviour

generalised anxiety disorders (similar to adult) chronic worrying about potential problems and threats, pathological worrying

worries may take particular forms at particular ages

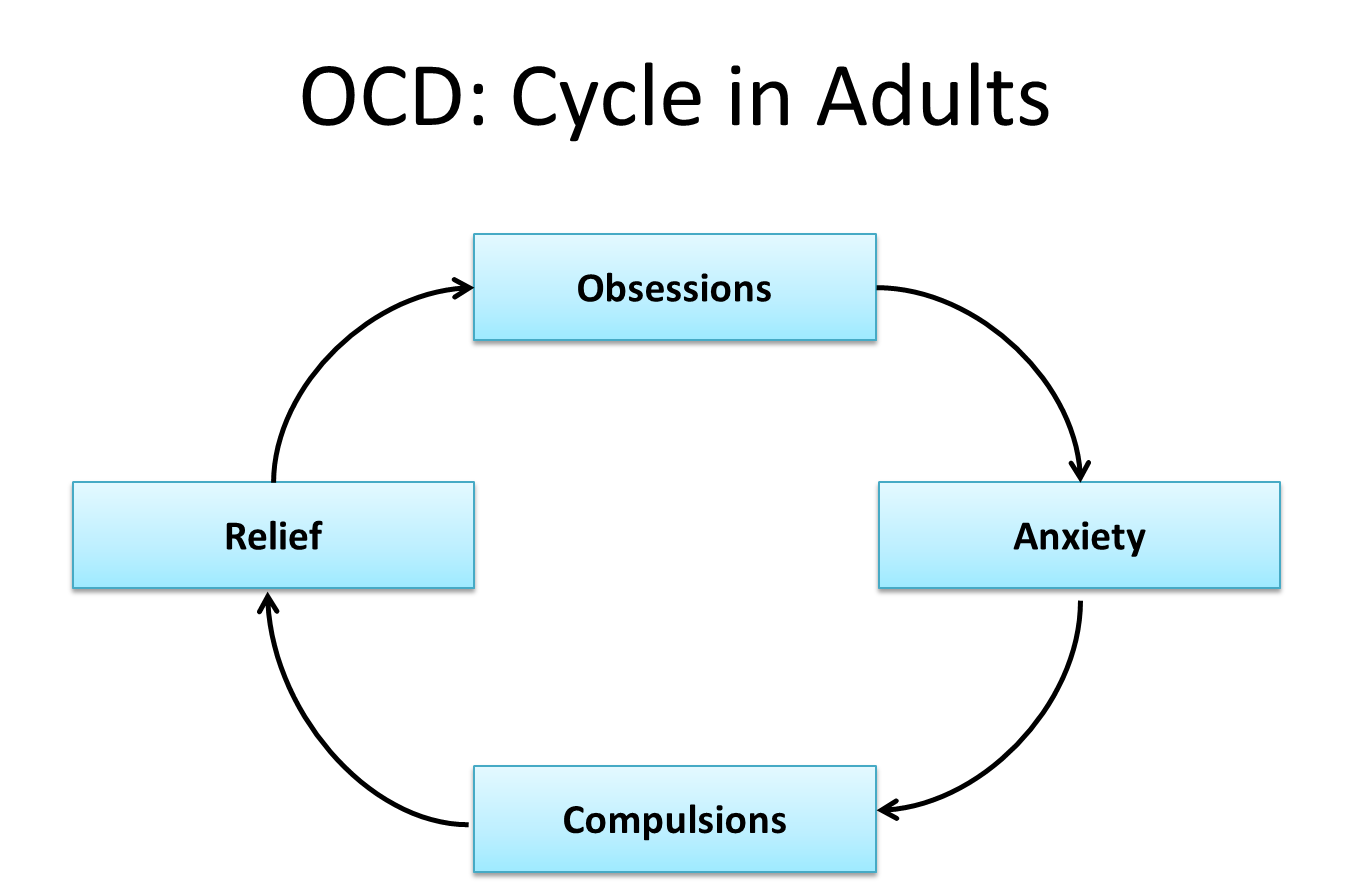

OCD: cycle in adults

Obsessions: intrusive and recurring thoughts that the individual finds disturbing and uncontrollable.

The obsessive thoughts are often associated with causing harm to oneself or a loved one.

Obsessive thoughts can also take the form of pathological doubting and indecision, and this may lead to sufferers developing repetitive behaviour patterns such as compulsive checking or washing.

Compulsions: represent repetitive or ritualised behaviour patterns that the individual feels driven to perform in order to prevent some negative outcome from happening.

e.g. ritualised and persistent checking of door/light switches.

The ritualised compulsions act to reduce stress and anxiety caused by the sufferer’s obsessive fears.

In most cases compulsions are clearly excessive and are recognised as so by the sufferer

Types of OCD:

Checking

Contamination

Symmetry and ordering

Ruminations/intrusive thoughts

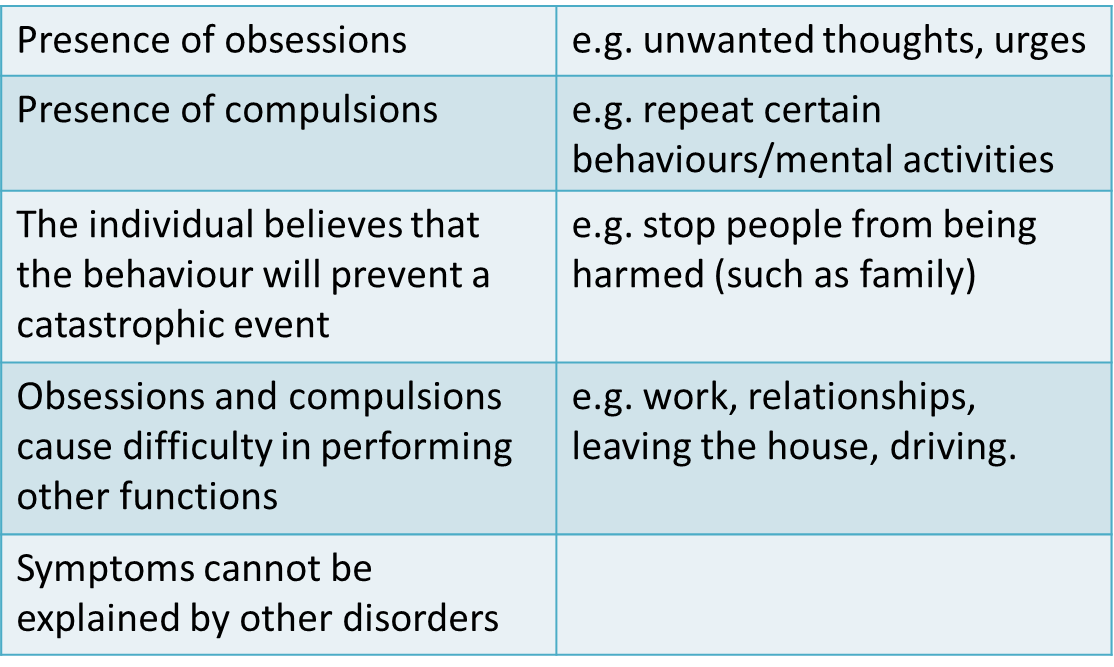

OCD: Diagnosis

Diagnosis is dependent on the obsessions and compulsions causing marked distressed, being time consuming or significantly interfering with the persons normal daily living.

Childhood anxiety developmental trajectory

4-7 years old separation from parents and fear of imaginary creatures

11-13 years old social threats

8 year olds have double the worries of 5 year olds

1% UK, some US studies 11%

Specific phobias

Normal – appear and disappear quickly – heights, water, spiders

Social phobia – begins as fear of strangers

Anxiety

Moderate heritability – 54%

Trauma

Modelling and exposure to information

parenting style; if the parent is overly involved with the child or not involved enough, either could lead to anxiety

COVID increased the rate of incidence of anxiety and has become a large area of research for psychologists

Childhood and adolescent depression

Difficult to recognise in young children:

‘Clingy’ behaviour school refusal, exaggerated fears

Somatic complaints: stomach aches and headaches, ways to physically describe their mental and psychological problems with their limited understanding and limited vocabulary

However, same as adult with minor amendments (DSM-5)

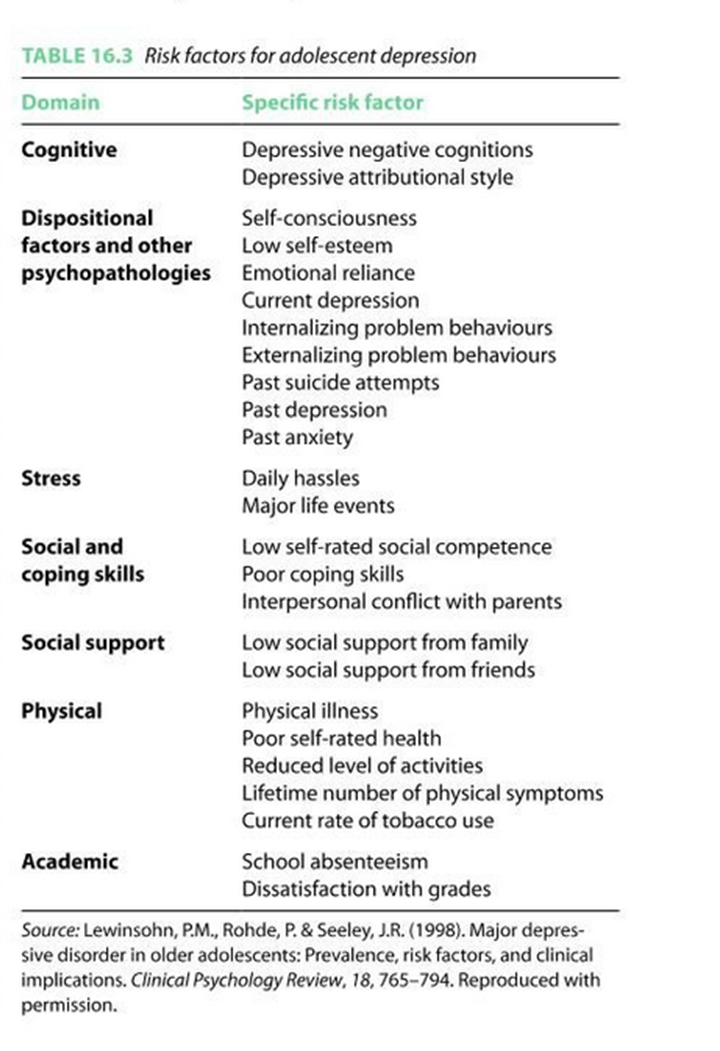

Causes of childhood and adolescent depression

Range of heritabilitys reported. Some studies find low in childhood increasing in adolescence.

In younger children abuse or neglect are risk factors, could be the case that depression is environmental in childhood, regarding amygdala interaction with the environment

Depression and childhood trauma: Leah’s story

ADHD, anxiety and depression linked to environment: dad passed away from cancer, mum then relied on alcohol and pills

could explain why heritability ranges, and gets higher as we get older

almost hospitalised due to suicidal tendencies

interventions such as therapy, schoolings and doing the hobbies she loves (like violin) aided in her recovery

Increased risk of depression in children of those with depression

Genes

Psychological

transmit low mood and attributions, may not be able to respond to child’s emotions, provide fewer enrichment activities

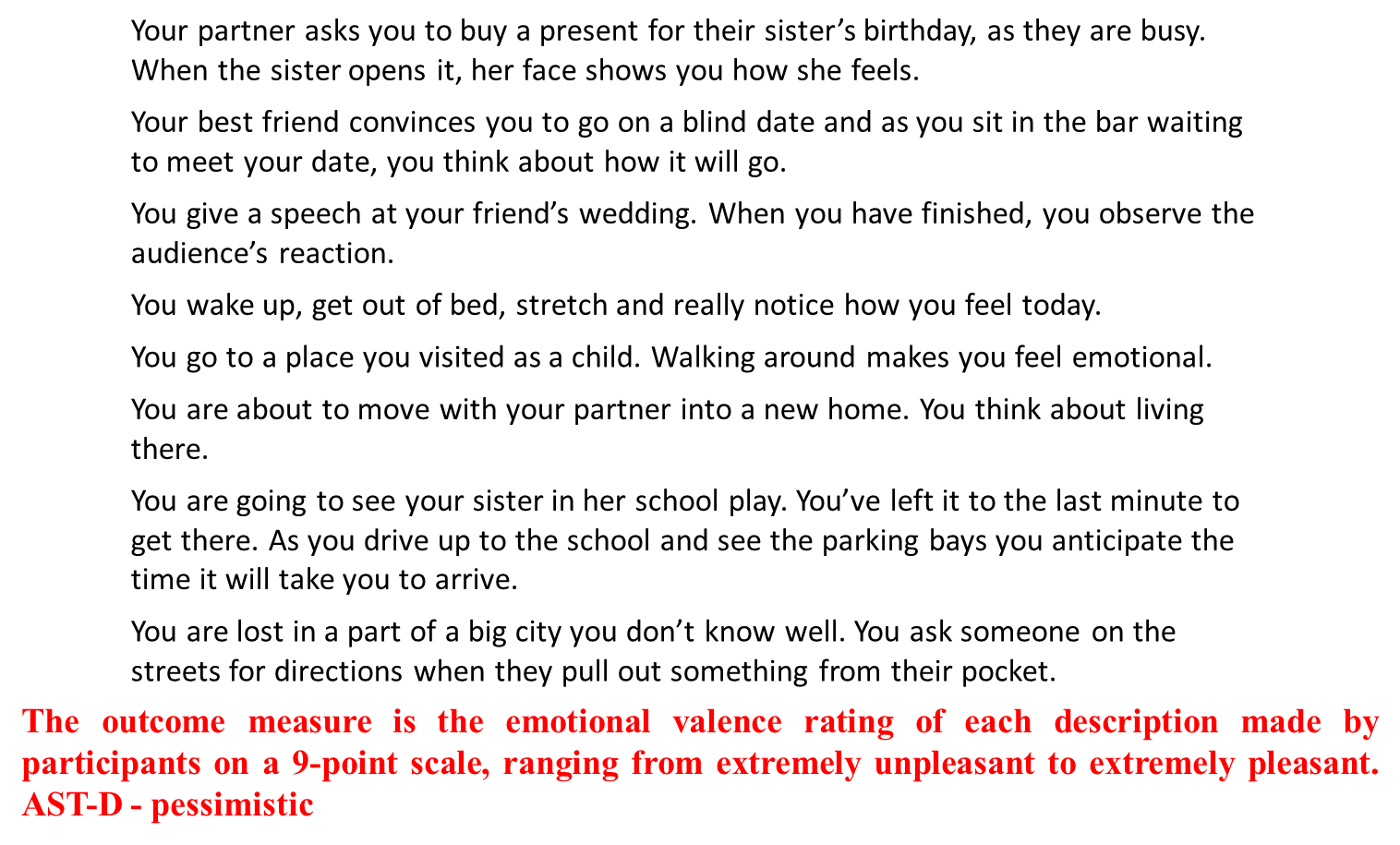

Ambiguous scenarios test AST-D - pessimistic

ADHD- two different forms commonly recognised

ADHD predominantly inattentive presentation

ADHD predominantly hyperactive/impulsive presentation

Combined presentation

Treatment of Childhood and Adolescent Psychological problems

drug treatments - similar to adult

What problems are there with drug treatments in childhood/ adolescence compared to adulthood?

brain’s are still developing

potential influences of hormones during puberty? how can we know if drug treatments are as effective if mood is effected/ not stable due to teen hormones

an ethical consideration: can the children give informed consent?

Study with a mouse (Science, 29 Oct 2004)

mouse anxiety test: open field test, put the mouse in a new environment and watch how much they move, the more the mouse walks about the less nervous the mouse is

if they’re scared they’ll probably freeze/ hide in the corner

given saline as a young mouse do a lot more moving about, mouse injected with prozac when young moved around a lot less, suggesting they were more nervous/ anxious

it could be argued that they didn’t move BECAUSE they were chilled out, but generally agreed to be the former

Treatment of childhood and adolescent psychological problems

family interventions:

Systemic family therapy –communication, structure and organisation, therapists helps family with their communication and organisations

Parent management training – not rewarding antisocial behaviours

Functional family therapy – strengthens relationships

•CBT

•Play therapy

Does making decisions in partnership with children and their parents improve child mental health?

Asked children if they were listened to and results generally showed that involving children in the decision making leads to better outcomes

Disruptive behaviour disorders (2 types) - externalising disorders

Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD)

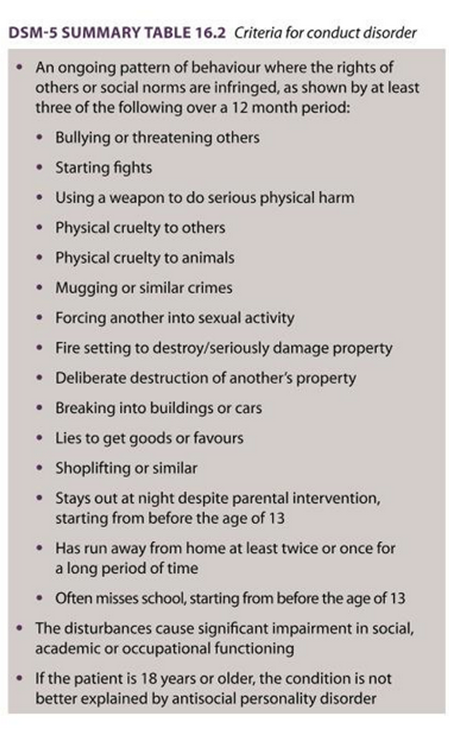

Conduct disorder (CD)

CD – before 10 years of age (childhood), after 10 year of age -adolescence.

Formerly known as externalising disorders

Anti-social personality disorder

happens if the disruptive behaviour disorders continue after the age of 18, this is the identification for it

Callous and unemotional (CU) traits

Distinguished by a persistent pattern of behaviour that reflects a disregard for others, and also a lack of empathy and generally deficient affect.

Children with CU traits have distinct problems in emotional and behavioural regulation that distinguish them from other antisocial youth and show more similarity to characteristics found in adult psychopathy.

Antisocial youth with CU traits tend to have a range of distinctive cognitive characteristics. They are often less sensitive to punishment cues, particularly when they are already keen for a reward.

CU traits are positively related to intellectual skills in the verbal realm.

Behavioural and emotional disorders in childhood: A brief overview for paediatricians

Abstract

DSM-5 and ICD-10 are the universally accepted standard criteria for the classification of mental and behaviour disorders in childhood and adults. The age and gender prevalence estimation of various childhood behavioural disorders are variable and difficult to compare worldwide. A review of relevant published literature was conducted, using a combination of search expressions including “childhood”, “behaviour”, “disorders” or “problems”. Impacts of behavioural issues on the individual, the family and the society are commonly associated with poor academic, occupational, and psychosocial functioning.

introduction

Mental health disorders in childhood

Mental health disorders (MHD) are very common in childhood and include

emotional-obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

anxiety,

depression,

oppositional defiance disorder (ODD),

conduct disorder (CD),

(ADHD)

developmental (speech/language delay, intellectual disability) disorders

pervasive (autistic spectrum) disorders.

Emotional and behavioural problems (EBP) or disorders (EBD) can also be classified as either “internalizing” (emotional disorders such as depression and anxiety) or “externalizing” (disruptive behaviours such as ADHD and CD).

What is normal for very young children and what is not?

What is seen as norm:

allow-intensity naughty

defiant and impulsive behaviour from time to time

losing one’s temper

destruction of property

deceitfulness/stealing in preschool children

what isn’t:

extremely difficult and challenging behaviours outside the norm for the age and level of development,

such as unpredictable, prolonged, and/or destructive tantrums

severe outbursts of temper loss are recognized as behaviour disorders.

More than 80% of pre-schoolers have mild tantrums sometimes but less than 10% will have daily tantrums, regarded as normative misbehaviours. Challenging behaviours and emotional difficulties are more likely to be recognized as “problems” rather than “disorders” during the first 2 years of life.

What issues occur more in later childhood

Emotional problems, such as

anxiety,

depression

post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

tend to occur in later childhood

They are difficult to recognise early by parents as many children have not developed appropriate vocabulary and comprehension to express their emotions intelligibly.

Many clinicians and carers find it difficult to distinguish between developmentally normal emotions (e.g., fears, crying) from the severe and prolonged emotional distresses regarded as disorders.

Emotional problems including disordered eating behaviour and low self-image are often associated with chronic medical disorders such as atopic dermatitis, obesity, diabetes and asthma, which lead to poor quality of life.

Identification and management of MHP

Identification and management of mental health problems in primary care settings such as routine Paediatric clinic or Family Medicine/General Practitioner surgery are cost-effective

their several desirable characteristics make it acceptable to children and young people (CYP) (e.g., no stigma, in local setting, and familiar providers).

models to improve the delivery of mental health services in the Paediatric/Primary care settings include coordination with external specialists, joint consultations, improved Mental Health training and more integrated on-site intervention with specialist collaboration.

CLINICAL PRESENTATIONS OF CHILDHOOD BEHAVIOURAL AND EMOTIONAL DISORDERS

Challenging behaviours - definitions

Any abnormal pattern of behaviour above the expected norm for age and level of development can be described as “challenging behaviour”.

defined as: “Culturally abnormal behaviour (s) of such an intensity, frequency or duration that the physical safety of the person or others is likely to be placed in serious jeopardy or behaviour which is likely to seriously limit or deny access to and use of ordinary community facilities”.

They can include self-injury, physical or verbal aggression, non-compliance, disruption of the environment, inappropriate vocalizations, and various stereotypies.

These behaviours can impede learning, restrict access to normal activities and social opportunities, and require a considerable amount of both manpower and financial resources to manage effectively.

what can challenging behaviour indicate?

Many instances can be interpreted as ineffective coping strategies for a young person trying to control what is going on around them.

Young people with disabilities (LD, Autism, and acquired neuro-behavioural disorders such as brain damage and post-infectious phenomena) may use challenging behaviour for specific purposes like for sensory stimulation, gaining attention of carers, avoiding demands or to express their limited communication skills.

People who have a diverse range of neurodevelopmental disorders are more likely to develop challenging behaviours.

what may increase challenging behaviour?

Some environmental factors increase the risk of challenging behaviour, including places offering limited opportunities for making choices, social interaction or meaningful occupation.

Other adverse environments are limited sensory input or excessive noise, unresponsive/unpredictable carers, predisposition to neglect and abuse, and where physical health needs are not promptly identified.

For example, the rates of challenging behaviour in teenagers and people in their early 20s is 30%-40% in hospital settings, compared to 5% to 15% among children attending schools for those with severe LD.

explain a common challenging behaviour

Aggression is a common, yet complex, challenging behaviour, and a frequent indication for referral to child and adolescent Psychiatrists.

It commonly begins in childhood,

more than 58% of preschool children demonstrate some aggressive behaviour

Aggression has been linked to several risk factors, including individual temperaments; the effects of disturbed family dynamics; poor parenting practices; exposure to violence and the influence of attachment disorders.

No single factor is sufficient to explain the development of aggressive behaviour.

Aggression is commonly diagnosed in association with other mental health problems including ADHD, CD, ODD, depression, head injury, mental retardation, autism, bipolar disorder, PTSD, or dyslexia

Disruptive behaviour problems

DBP include:

ADHD

oppositional defiant disorder (ODD)

and conduct disorder (CD). .

They constitute the commonest EBPs among CYP.

Recent evidence suggests that DBPs should be regarded as a multidimensional phenotype rather than comprising distinct subgroups

ADHD

the commonest neuro-behavioural disorder in children and adolescents,

prevalence ranging between 5% and 12% in the developed countries.

it is characterized by levels of hyperactivity, impulsivity and inattention that are disproportionately excessive for the child’s age and development.

The ICD-10 does not use the term “ADHD” but “hyperkinetic disorder”, which is equivalent to severe ADHD.

DSM-5 distinguishes between three subtypes: predominantly hyperactive/impulsive, predominantly inattentive and combined types

Compulsive disorder

refers to severe behaviour problems

characterized by repetitive and persistent manifestations of serious aggressive or non-aggressive behaviours against people, animals or property

such as being defiant, belligerent, destructive, threatening, physically cruel, deceitful, disobedient or dishonest, excessive fighting or bullying, fire-setting, stealing, repeated lying, intentional injury, forced sexual activity and frequent school truancy.

Children with CD often have trouble understanding how other people think, described as callous-unemotional.

They may falsely misinterpret the intentions of other people as being mean.

They may have immature language skills, lack appropriate social skills to establish and maintain friendships, which aggravates their feelings of sadness, frustration and anger

Subtypes of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (based on DSM-5)

predominantly inattentive (ADD)

criteria: 6 of 9 inattentive symptoms

details: fails to pay close attention to details or makes careless mistakes, has difficulty sustaining attention, does not appear to listen, struggles to follow through on instructions, has difficulty with organisation, avoids or dislikes tasks requiring a lot of thinking, loses things, is easily distracted

predominantly hyperactivity/ impulsivity

criteria: 6 of 9 hyperactivity/ impulsivity symptoms

details: squirms and fidgets, can’t stay seated, run/climbs excessively, can’t play/ works quietly, “on the go”/”driven by a motor”, blurts out answers, is unable to wait for his turn, intrudes/ interrupts others, talks excessively

combined ADHD

both criteria for the previous two

DSM-5 definition of conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder

oppositional defiant disorder

A pattern of angry/irritable mood, argumentative/defiant behaviour, or vindictiveness lasting at least 6 mo as evidenced by at least 4 of 8 symptoms from the following categories, and exhibited during interaction with an individual that is not a sibling

Angry/ irritable mood: (1) often loses temper; ("2) is often angry and resentful

argumentative/ defiant behaviour: often argues with authority figures or, for children and adolescents, with adults; (5) often actively defies or refuses to comply with requests from authority figures or with rules; (6) often deliberately annoys others; (7) often blames others for his or her mistakes/ behaviour

Vindictiveness: (8) Has been spiteful or vindictive at least twice within the past 6 mo

Note: The persistence and frequency of these behaviours distinguish a behaviour within normal limits from a behaviour that is symptomatic and the behaviour should occur at least once per week for at least 6 mo

The disturbance in behaviour is associated with distress in the individual or others in his or her immediate social context (e.g., family, peer group, work colleagues), or it impacts negatively on social, educational, occupational, or other important areas of functioning

The behaviours do not occur exclusively during the course of a psychotic, substance use, depressive, or bipolar disorder. Also, the criteria are not met for disruptive mood dysregulation disorder

Specify current severity: Mild; moderate or severe based on number of settings with symptoms shown

conduct disorder

A repetitive and persistent pattern of behaviour where basic rights of others or major age-appropriate societal norms or rules are violated, as manifested by the presence of at least 3 of the following 15 criteria in the past 12 mo from the categories below, with at least one criterion present in the past 6 mo

Aggression to people and animals: (1) often bullies, threatens or intimidates others; (2) often initiates physical fights; (3) has used a weapon that can cause serious physical harm to others; (4) has been physically cruel to people; (5) has been physically cruel to animals; (6) has stolen while confronting a victim like mugging or armed robbery; (7) has forces someone into sexual activity

destruction of property: (8) has deliberately engaged in fire setting with the intention of causing serious damage; (9) has deliberately destroyed others’ property (other than by fire setting)

deceitfulness or theft: (10) has broken into someone else’s house, building or car; (11) often lies to obtain goods or favours to avoid obligations (i.e. cons others); (12) has stolen items of nontrivial value without confronting a victim (e.g. shoplifting, but without breaking and entering; forgery)

serious violations of rules: (13) often stays out at night despite parental prohibitions, beginning before age 13; (14) has run away from home overnight at least twice while living in the parental or parental surrogate home, or once without returning for a lengthy period; (15) is often truant from school, beginning before 13yrs

The disturbance in behaviour causes clinically significant impairment in social, academic, or occupational functioning

If the individual is age 18 yr or older, criteria are not met for antisocial personality disorder

Specify whether: Childhood-onset type (prior to age 10 yr); Adolescent-onset type or Unspecified onset

Specify if: With limited prosocial emotions: Lack of remorse or guilt; Callous-lack of empathy; Unconcerned about performance or Shallow or deficient affect

Specify current severity: Mild; Moderate or Severe

ICD-10

It also requires the presence of three symptoms from the list of 15, and duration of at least 6 mo.

There are four divisions of conduct disorder: Socialised conduct disorder, unsocialised conduct disorder, conduct disorders confined to the family context and oppositional defiant disorder

why are children and young people referred for psychological and psychiatric treatment?

CD is the commonest reason for CYP referral for psychological and psychiatric treatment.

Roughly 50% of all CYP with a MHD have a CD.

About 30%-75% of children with CD also have ADHD and 50% of them will also meet criteria for at least one other disorder including Mood, Anxiety, PTSD, Substance abuse, ADHD, learning problems, or thought disorders.

Majority of boys have an onset of CD before the age of 10 years, while girls tend to present mainly between 14 and 16 years of age.

Most CYP with CD grow out of this disorder, but a minority become more dissocial or aggressive and develop antisocial personality disorder as adults.

ODD is considered to be the mildest and commonest of the DBPs

prevalence estimates of 6%-9% for pre-schoolers; boys outnumbering girls by at least two to one

CYP with ODD are typically openly hostile, negativistic, defiant, uncooperative, and irritable. They lose their tempers easily and are mean and spiteful towards others.

They are mostly defiant towards authority figures, but they may also be hostile to their siblings or peers.

This pattern of adversarial behaviour significantly negatively impact on their lives at home, school, and wider society, and seriously impairs all their relationships.

Emotional problems

Emotional problems in later childhood

Emotional problems in later childhood include panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), separation anxiety, social phobia, specific phobias, OCD and depression.

Mild to moderate anxiety is a normal emotional response to many stressful life situations.

Anxiety is regarded as a disorder when it is disproportionately excessive in severity in comparison to the gravity of the triggering circumstances, leading to abnormal disruption of daily routines.

Panic disorder is characterized by panic attacks untriggered by external stimuli.

GAD is characterized by generalized worry across multiple life domains.

Separation anxiety disorder is characterized by fear related to actual or anticipated separation from a caregiver.

Social anxiety disorder is characterized by fear of social situations where peers may negatively evaluate the person.

common manifestations of anxiety disorders

Common manifestations include physical symptoms such as increased heart rate, shortness of breath, sweating, trembling, shaking, chest pain, abdominal discomfort and nausea.

Other symptoms include worries about things before they happen, constant concerns about family, school, friends, or activities, repetitive, unwanted thoughts (obsessions) or actions (compulsions), fears of embarrassment or making mistakes, low self-esteem and lack of self-confidence.

Depression

Depression often occurs in children under stress, experiencing loss, or having attentional, learning, conduct or anxiety disorders and other chronic physical ailments.

It tends to run in families.

Symptoms of depression are diverse and often mimic other physical and neurodevelopmental problems, including low mood, frequent sadness, tearfulness, crying, decreased interest or pleasure in almost all activities; or inability to enjoy previously favourite activities, hopelessness, persistent boredom; low energy, social isolation, poor communication, low self-esteem and guilt, feelings of worthlessness, extreme sensitivity to rejection or failure, increased irritability, agitation, anger, or hostility, difficulty with relationships, frequent complaints of physical illnesses such as headaches and stomach aches, frequent absences from school or poor performance in school, poor concentration, a major change in eating and/or sleeping patterns, weight loss or gain when not dieting, talk of or efforts to run away from home, thoughts or expressions of suicide or self-destructive behaviour.

DMDD

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) is a childhood disorder characterized by a pervasively irritable or angry mood recently added to DSM-5.

The symptoms include frequent episodes of severe temper tantrums or aggression (more than three episodes a week) in combination with persistently negative mood between episodes, lasting for more than 12 mo in multiple settings, beginning after 6 years of age but before the child is 10 years old.

Autistic spectrum and pervasive development disorder

Pervasive developmental disorders

DSM-IV-TR and the ICD-10 defined the diagnostic category of pervasive developmental disorders (PDD) as the umbrella terminology used for a group of five disorders characterized by pervasive “qualitative abnormalities in reciprocal social interactions and in patterns of communication, and by a restricted, stereotyped, repetitive repertoire of interests and activities” affecting “the individual’s functioning in all situations”. These included:

autism,

asperger syndrome,

childhood disintegrative disorder (CDD),

pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS)

and Rett syndrome.

Autism and Asperger Syndrome are the most widely recognised and clinically diagnosed.

CDD is a term used to describe children who had a period of normal development for the first 2-3 years before a relatively acute onset of regression and emergence of autistic symptoms.

PDD-NOS was used, particularly in the US, to describe individuals who have autistic symptoms, but do not meet the full criteria for Autism or Asperger’s Syndrome, denote a milder version of Autism, or to describe atypical autism symptoms emerging after 30 mo of age, and autistic individuals with other co-morbid disorders.

PDD in the DSM-5

The category of PDD has been removed from DSM-5 and replaced with Autism Spectrum disorders (ASD).

ASD is diagnosed primarily from clinical judgment usually by a multidisciplinary team, with minimal support from diagnostic instruments.

Most individuals who received diagnosis based on the DSM-IV should still maintain their diagnosis under DSM-5, with some studies confirming that 91% to 100% of children with PDD diagnoses from the DSM-IV retained their diagnosis under the ASD category using the new DSM-5, while a systematic review has found a slight decrease in the rate of ASD with DSM-5

DSM-5 criteria for autism spectrum disorders

Persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts, as manifested by 3 out 3 of the following:

Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, ranging, for example, from abnormal social approach and failure of normal back-and-forth conversation; to reduced sharing of interests, emotions, or affect; to failure to initiate or respond to social interactions

Deficits in nonverbal communicative behaviours used for social interaction, ranging, for example, from poorly integrated verbal and nonverbal communication; to abnormalities in eye contact and body language or deficits in understanding and use of gestures; to a total lack of facial expressions and nonverbal communication

Deficits in developing, maintaining, and understanding relationships, ranging, for example, from difficulties adjusting behaviour to suit various social contexts; to difficulties in sharing imaginative play or in making friends; to absence of interest in peers

Restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests, or activities, as manifested by at least two out of 4 of the following, currently or by history

Stereotyped or repetitive motor movements, use of objects, or speech (e.g., simple motor stereotypies, lining up toys or flipping objects, echolalia, idiosyncratic phrases)

Insistence on sameness, inflexible adherence to routines, or ritualized patterns or verbal nonverbal behaviour (e.g., extreme distress at small changes, difficulties with transitions, rigid thinking patterns, greeting rituals, need to take same route or eat food every day)

Highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus (e.g., strong attachment to or preoccupation with unusual objects, excessively circumscribed or perseverative interest)

Hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input or unusual interests in sensory aspects of the environment (e.g., apparent indifference to pain/temperature, adverse response to specific sounds or textures, excessive smelling or touching of objects, visual fascination with lights or movement)

Symptoms must be present in early developmental period (but may not fully manifest until social demands exceed limited capacities, or may be masked by learned strategies in later life)

Symptoms cause clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of current functioning

Specify if

With or without accompanying intellectual impairment With or without accompanying language impairment

Associated with a known medical or genetic condition or environmental factor

Specify current severity based on social communication impairments and restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour

interventions for those with ASD

There are many intervention approaches and strategies for supporting individuals with ASD.

These interventions need to individualized and be closely tailored to the level of social and linguistic abilities, cultural background, family resources, learning style and degree of communication skills.

Various communication enhancement strategies have been designed to manage ASD, including augmentative and alternative communication (AAC), Facilitated Communication, computer-based instruction and video-based instruction. Several behavioural and psychological interventions have also been used successfully in managing ASD children, including applied behaviour analysis and functional communication training

Summary of common social communication enhancement strategies

Method→ description

augmentative and alternative communication → Supplements/replaces natural speech and/or writing with aided [e.g., Picture Exchange Communication System, line drawings, Blissymbols, speech generating devices, and tangible objects] and/or unaided (e.g., manual signs, gestures, and finger spelling) symbols

Effective in decreasing maladaptive or challenging behaviour such as aggression, self-injury and tantrums, promotes cognitive development and improves social communication

Activity schedules/ visual supports → Using photographs, drawings, or written words that act as cues or prompts to help individuals complete a sequence of tasks/activities or behave appropriately in various settings

Scripts are often used to promote social interaction, initiate or sustain interaction

Computer-/ video-based instruction → Use of computer technology or video recordings for teaching language skills, social skills, social understanding, and social problem solving

Summary of common behavioural modification strategies for management of childhood emotional and behavioural disorder

Method → description

ABA → Uses principles of learning theory to bring about meaningful and positive change in behaviour, to help individuals build a variety of skills (e.g., communication, social skills, self-control, and self-monitoring) and help generalize these skills to other situations

Discrete trial training → A one-to-one instructional approach based on ABA to teach skills in small, incremental steps in a systematic, controlled fashion, documenting stepwise clearly identified antecedent and consequence (e.g., reinforcement in the form of praise or tangible rewards) for desired behaviours

Functional communication training → Combines ABA procedures with communicative functions of maladaptive behaviour to teach alternative responses and eliminate problem behaviours

pivotal response treatment → A play-based, child-initiated behavioural treatment, designed to teach language, decrease disruptive behaviours, and increase social, communication and academic skills, building on a child’s initiative and interests

positive behaviour support → Uses ABA principles with person-centred values to foster skills that replace challenging behaviours with positive reinforcement of appropriate words and actions. PBS can be used to support children and adults with autism and problem behaviours

Self-management → Uses interventions to help individuals learn to independently regulate, monitor and record their behaviours in a variety of contexts, and reward themselves for using appropriate behaviours. It’s been found effective for ADHD and ASD children

Time delay → It gradually decreases the use of prompts during instruction over time. It can be used with individuals regardless of cognitive level or expressive communication abilities

incidental teaching → Utilizes naturally occurring teaching opportunities to reinforce desirable communication behaviour

anger management → Various strategies can be used to teach children how to recognise the signs of their growing frustration and learn a range of coping skills designed to defuse their anger and aggressive behaviour, teach them alternative ways to express anger, including relaxation techniques and stress management skills

Social (pragmatic) communication disorder

Social (pragmatic) communication disorder (SCD) is a new diagnosis included under Communication Disorders in the Neurodevelopmental Disorders section of the DSM-5.

It is characterized by persistent difficulties with using verbal and nonverbal communication for social purposes, which can interfere with interpersonal relationships, academic achievement and occupational performance, in the absence of restricted and repetitive interests and behaviours.

Some consider that CYP with SCD present with similar but less severe restricted and repetitive interests and behaviours (RRIBs) characteristic of children on the autistic spectrum.

SCD is thought to occur more frequently in family members of individuals with autism

DSM-5 criteria for social (pragmatic) communication disorder:

Persistent difficulties in the social use of verbal and nonverbal communication as manifested by all of the following

Deficits in using communication for social purposes, such as greeting and sharing information, in a manner that is appropriate for social context

Impairment in the ability to change communication to match context or the needs of the listener, such as speaking differently in a classroom than on a playground, talking differently to a child than to an adult, and avoiding use of overly formal language

Difficulties following rules for conversation and storytelling, such as taking turns in conversation, rephrasing when misunderstood, and knowing how to use verbal and nonverbal signals to regulate interaction

Difficulties understanding what is not explicitly stated (e.g., making inferences) and nonliteral or ambiguous meaning of language (e.g., idioms, humour, metaphors, multiple meanings that depend on the context for interpretation)

The deficits result in functional limitations in effective communication, social participation, social relationships, academic achievement, or occupational performance, individually or in combination

The onset of the symptoms is in the early developmental period (but deficits may not become fully manifest until social communication demands exceed limited capacities)

The symptoms are not attributable to another medical or neurological condition or to low abilities in the domains of word structure and grammar, and are not better explained by autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability (intellectual developmental disorder), global developmental delay, or another mental disorder

Pathological demand avoidance or Newson’s syndrome

Pathological demand avoidance (PDA) or Newson’s Syndrome was first used in 2003 to describe some CYP with autistic symptoms who showed some challenging behaviours.

It is characterized by exceptional levels of demand avoidance requested by others, due to high anxiety levels when the individuals feel that they are losing control.

Avoidance strategies can range from simple refusal, distraction, giving excuses, delaying, arguing, suggesting alternatives and withdrawing into fantasy, to becoming physically incapacitated (with an explanation such as “my legs don’t work”) or selectively mute in many situations.

If they feel threatened to comply, they may become aggressive, best described as a “panic attack”, apparently intended to shock. They tend to resort to “socially manipulative” behaviours. The outrageous acts and lack of concern for their behaviour appears to draw parallels with conduct problems (CP) and callous-unemotional traits (CUT), but reward-based techniques, effective with CP and CUT, seem not to work in people with PDA.

PDA is currently neither part of the DSM-5 nor the ICD-10.

demand avoidance: ASD Vs PDA

a common characteristic of CYP with ASD

it becomes pathological when the levels are disproportionately excessive, and normal daily activities and relationships are negatively impaired

Unlike typically autistic children, people with PDA tend to have much better social communication and interaction skills, and are consequently able to use these abilities to their advantage. They often have highly developed social mimicry and role play, sometimes becoming different characters or personas. The people with PDA appear to retain a keen awareness of how to “push people’s buttons”, suggesting a level of social insight when compared to CYP with Autism.

On the other hand, children with PDA exhibit higher levels of emotional symptoms compared to those with ASD or CD. They often experience excessive mood swings and impulsivity. While the prevalence of ASD in boys is more than four times higher compared to that of girls, the risk of developing PDA appears to be the same for both boys and girls.

O’Nions et al have recently reported on the development and preliminary validation of the “Extreme Demand Avoidance Questionnaire” (EDA-Q), designed to quantify PDA traits based on parent-reported information, with good sensitivity (0.80) and specificity (0.85).

PREVALENCE OF BEHAVIOURAL AND EMOTIONAL DISORDERS IN CHILDHOOD

Accurate estimation of various childhood EBPs is difficult due to the problems of research methodologies relying on subjective assessments and varying definitions used. Between 10% and 20% of CYP are affected annually by MHDs, and the rates are very similar across different racial and ethnic groups.

However, poverty and low socioeconomic status are risk factors that appear to increase the rate of MHDs across populations. A 2001 WHO report indicated the 6-mo prevalence rate for any MHD in CYP, up to age 17 years, to be 20.9%, with disruptive behaviour disorders (DBD) at 10.3%, second only to Anxiety disorders at 13%. About 5% of CYP in the general population suffer from Depression at any given point in time, which is more prevalent among girls (54%).

A CAMH survey by the office of National Statistics (ONS) in 1999 and 2004, comprising 7977 interviews from parents, children and teachers, found the prevalence of MHD among CYP (aged 5-16 years) to be 6% for conduct problems, 4% for emotional problems (Depression or Anxiety) and 1.5% for Hyperkinetic disorders. A similar survey in the United States between 2005 and 2011, the National survey of children’s health (NSCH) involving 78042 households, indicated that 4.6% of CYP aged 3-17 years had a history DBD, with prevalence twice as high among boys as among girls (6.2% vs 3.0%), Anxiety (4.7%), Depression (3.9%), and ASD (1.1%). Reported prevalence rates for DMDD range from 0.8% to 3.3% with the highest rate in preschool children

AETIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS FOR CHILDREN’S BEHAVIOURAL AND EMOTIONAL DISORDERS

The exact causes of various childhood EBPs are unknown. Several studies have identified various combinations of genetic predisposition and adverse environmental factors that increase the risk of developing any of these disorders. These include perinatal, maternal, family, parenting, socio-economic and personal risk factors[53]. Table 7 summarizes the evidence for various risk factors associated with development of childhood EBPs.

There is ample evidence supporting the genetic inheritability of many EBDs in CYP from their parents. From a prospective study of 209 parents along with their 331 biological offsprings, moderate inheritability (r = 0.23, P < 0.001) between parental and offspring CD was found[74]. Anxiety seems to be transmissible from mothers to their preschool children, through both genetic factors and also through behaviour modelling and an anxious style of parenting[6].

A developmental taxonomy theory has been proposed by Patterson et al[75] to help understand the mechanisms underlying early onset and course of CPs. They described the vicious cycle of non-contingent parental responses to both prosocial and antisocial child behaviour leading to the inadvertent reinforcement of child behaviour problems. Parents’ engagement in “coercive cycles” lead to children learning the functional value of their aversive behaviours (e.g., physical aggression) for escape and avoidance from unwanted interactions, ultimately leading to the use of heightened aversive behaviours from both the child and parents to obtain social goals. This adverse child behavioural training combined with social rejection often lead to deviant peer affiliation and delinquency in adolescence

Summary of common risk factors for development of childhood emotional and behavioural disorder:

Domain → characteristic examples

maternal psychopathology (mental health status) → Low maternal education, one or both parents with depression, antisocial behaviour, smoking, psychological distress, major depression or alcohol problems, an antisocial personality, substance misuse or criminal activities, teenage parental age, marital conflict, disruption or violence, previous abuse as a child and single (unmarried status)

adverse perinatal → Maternal gestational moderate alcohol drinking, smoking and drug use, early labour onset, difficult pregnancies, premature birth, low birth weight, and infant breathing problems at birth

poor child-parent relationships → Poor parental supervision, erratic harsh discipline, parental disharmony, rejection of the child, and low parental involvement in the child’s activities, lack of parental limit setting

adverse family life → Dysfunctional families where domestic violence, poor parenting skills or substance abuse are a problem, lead to compromised psychological parental functioning, increased parental conflict, greater harsh, physical, and inconsistent discipline, less responsiveness to children’s needs, and less supportive and involved parenting

household tobacco exposure → Several studies have shown a strong exposure–response association between second-hand smoke exposure and poor childhood mental health

poverty and adverse socio-economic environment → Personal and community poverty signs including homelessness, low socio-economic status, overcrowding and social isolation, and exposure to toxic air, lead, and/or pesticides or early childhood malnutrition often lead to poor mental health development Chronic stressors associated with poverty such as single-parenthood, life stress, financial worries, and ever-present challenges cumulatively compromise parental psychological functioning, leading to higher levels of distress, anxiety, anger, depressive symptoms and substance use in disadvantaged parents

Chronic stressors in children also lead to abnormal behaviour pattern of ‘reactive responding’ characterized by chronic vigilance, emotional reacting and sense of powerlessness

early age of onset → Early starters are likely to experience more persistent and chronic trajectory of antisocial behaviours

Physically aggressive behaviour rarely starts after age 5

child’s temperament → Children with difficult to manage temperaments or show aggressive behaviour from an early age are more likely to develop disruptive behavioural disorders later in life

Chronic irritability, temperament and anxiety symptoms before the age of 3 yr are predictive of later childhood anxiety, depression, oppositional defiant disorder and functional impairment

developmental delay and intellectual disabilities → Up to 70% of preschool children with DBD are more than 4 times at risk of developmental delay in at least one domain than the general population

Children with intellectual disabilities are twice as likely to have behavioural disorders as normally developing children

Rate of challenging behaviour is 5% to 15% in schools for children with severe learning disabilities but is negligible in normal schools

Child’s gender → Boys are much more likely than girls to suffer from several DBD while depression tends to predominantly affect more girls than boys

Unlike the male dominance in childhood ADHD and ASD, PDA tends to affect boys and girls equally

NEUROBIOLOGY OF CHILDHOOD BEHAVIOURAL AND EMOTIONAL DISORDERS

Conflicting findings have been reported in the brain structural variations among CYP with EBPs using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies. The most consistently reported structural abnormalities associated with the DBD include reduced grey matter volume (GMV) in the amygdala, frontal cortex, temporal lobes, and the anterior insula, which is involved in part of a network related to empathic concern for others. Reduced GMV along the superior temporal sulcus has also been found, particularly in girls[77]. A decreased overall mean cortical thickness, thinning of the cingulate and prefrontal cortices; and decreased grey matter density in different brain regions have been reported[78].

Subtle neurobiological changes in different parts of the brain of CYP with EBPs have been reported from many research studies of functional scans. Peculiar brain changes have been found in the hypothalamus, inferior and superior parietal lobes, right amygdala and anterior insula[79]. Functional MRI studies have demonstrated less activation in the temporal cortex in violent adult offenders[80] and in antisocial and psychopathic individuals[81] compared to non-aggressive offenders.

Reduced basal Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis activity has been reported in relation to childhood DBDs and exposure to abuse and neglect[82]. It has been hypothesized that high levels of prenatal testosterone exposure appears to be part of the complex aetiology of EBDs, providing possible explanation for the higher prevalence in males for DBDs, by increasing susceptibility to toxic perinatal environments such as exposure to maternal nicotine and alcohol in pregnancy

Complications of childhood behavioural and emotional disorders:

EBDs in childhood, if left untreated, may have negative short-term and long-term effects on an individual’s personal, educational, family and later professional life. CD has been linked to failure to complete schooling, attaining poor school achievement, poor interpersonal relationships, particularly family breakup and divorce, and experience of long-term unemployment. DBPs in parents have been linked to the abuse of their offspring, thereby increasing their risk of developing CD[84,85]. Children presenting with hyperactivity-inattention behaviours are more likely to have a more favourable educational outcome compared with those with aggression or oppositional behaviours[86,87].

A high prevalence of sleep disturbances is associated with various childhood EBPs. Sleep problems in early childhood is associated with increased prevalence of later Anxiety disorders and ODD[88,89].

Several studies have confirmed a strong relationship between early childhood EBPs and poor future long-term physical and mental health outcomes. Chronic irritability in preschool children, CD and ODD in older children each may be predictive of any current and lifetime Anxiety, Depression and DBDs in later childhood, Mania, Schizophrenia, OCD, major depressive disorder and panic disorder[84,90-92]. Individuals on the adolescent-onset CP path often consume more tobacco and illegal drugs and engage more often in risky sexual behaviour, self-harm, and have increased risk of PTSD, than individuals without childhood conduct problems. They also frequently experience parenting difficulties, including over-reactivity, lax and inconsistent discipline, child physical punishment and lower levels of parental warmth and sensitivity[74,84,93,94]. Approximately 40%-50% of CYP with CD are at the risk of developing antisocial personality disorder in adulthood[84]. Other potential complications include adverse mental and physical health outcomes, social justice system involvement including incarceration, substance use and abuse, alcoholism, homelessness, poverty and domestic abuse[95,96].

An analysis of several Scandinavian studies up to the 1980s has shown higher rates of violent death, estimated to be almost five times higher than expected among young people with previous MHD, with common associated predictive factors including behavioural problems, school problems, and co-morbid alcohol or drug abuse and criminality

Assessment and diagnosis of childhood behavioural and emotional disorders:

Assessment through detailed history taking as well as observation of a child’s behaviour are indispensable sources of information required for clinical diagnosis of EBPs[1]. This should include general medical, developmental, family, social, educational and emotional history. Physical and neurological examination should include assessment of vision, hearing, dysmorphic features, neuro-cutaneous stigmata, motor skills and cognitive assessment. Condition-specific and generic observer feedback on screening rating scales and questionnaires can be used to complement direct clinical observations.

There is no single gold-standard diagnostic tool available for the diagnosis of EBDs, which largely depends on the clinical skills of an integrated collaboration of multi-professional experts. Diagnosis relies on interpretation of subjective multi-source feedback from parents or carers, teachers, peers, professional or other observers provided through a number of psychometric questionnaires or screening tools[98]. Significant discrepancies between various respondents are quite common and clinical diagnosis cannot rely on the psychometric tools alone. There is evidence from the literature suggesting that parents have a tendency to over-report symptoms of ODD and CD in children compared to the teachers[99].

There are several screening tools that are used for assessing the risk of MHD among CYP. The tools help to identify which individuals would require more in-depth clinical interventions[100]. Supplement material shows a list of common Mental Health screening and assessment tools, summarizing their psychometric testing properties, cultural considerations and costs. The commonest behaviour screening tools include the Behavioral and Emotional Screening System (BESS; ages 3-18 years), the Behavior Assessment System for Children-2nd edition, Pediatric Symptom Checklist (PSC), the Ages and Stages Questionnaire-Social Emotional (ASQ-SE, Ages 0 to 5 years) and the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA), for children aged 1.5 years through adulthood.

Management of behavioural and emotional disorders in children:

Identification of appropriate treatment strategies depend on careful assessment of the prevailing symptoms, the family and caregiver’s influences, wider socio-economic environment, the child’s developmental level and physical health. It requires multi-level and multi-disciplinarian approaches that include professionals such as Psychologists, Psychiatrists, Behavioural Analysts, Nurses, Social care staff, Speech and language Therapists, Educational staff, Occupational Therapists, Physiotherapists, Paediatricians and Pharmacists. Use of pharmacotherapy is usually considered only in combination with psychological and other environmental interventions[15].

Holistic management strategies will include various combinations of several interventions such as child- and family-focused psychological strategies including Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), behavioural modification and social communication enhancement techniques, parenting skills training and psychopharmacology. These strategies can play significant roles in the management of children with a wide range of emotional, behavioural and social communication disorders. Effective alternative educational procedures also need to be implemented for the school age children and adolescents.

In early childhood, similar parenting strategies have been found useful to manage several apparently dissimilar EBPs (e.g., infant feeding or sleeping problems, preschool tantrums, disruptive and various emotional problems). This may suggest there is a common maintaining mechanism, which is probably related to poor self-regulation skills, involving the ability to control impulses and expressions of emotion[101].

Several studies have confirmed the effectiveness of various psychological and pharmacologic therapies in the management of childhood EBDs. A meta-analysis of thirty-six controlled trials, involving 3042 children (mean sample age, 4.7 years), evaluating the effect of psychosocial treatments including parenting programmes on early DBPs, demonstrated large and sustained effects (Hedges’g = 0.82), with the largest effects for general externalizing symptoms and problems of oppositionality and non-compliance, and were weakest, relatively speaking, for problems of impulsivity and hyperactivity[102].

The treatment of CD among CYP with callous-unemotional traits is still at early stages of research. The mainstay of management for CDs includes individual behavioural or cognitive therapy, psychotherapy, family therapy and medications

Parental skills training:

Any challenging behaviour from CYP is likely to elicit persistent negative reactions from many parents, using ineffective controlling strategies and a decrease in positive responses[104]. There is evidence from published research that social-learning and behaviourally based parent training is capable of producing lasting improvement in children with callous-unemotional traits or CD, reducing externalizing problems for children with DBDs, leading to significant parent satisfaction, particularly when delivered early in childhood[84,105-107]. These interventions are typically delivered in a group format, one 2-h session per week for 4-18 wk, by trained leaders, with the focus on improving parenting skills to manage child behaviour, where parents typically learn to identify, define and observe problem behaviours in new ways, as well as learn strategies to prevent and respond to oppositional behaviour[108,109].

Pooled estimates from a review of 37 randomised controlled studies identified a statistically significant improvement on several rating scales among children with CD up to the age of 18 years[23]. A previous meta-analysis of 24 studies confirmed that Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) demonstrated significantly larger effect sizes for reducing negative parent behaviours, negative child behaviours, and caregiver reports of child behaviour problems than did most or all forms of Positive Parenting Programme (Triple P)[110]. A recent Cochrane review of 13 studies confirmed the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of group-based parenting interventions for alleviating child conduct problems, enhancing parental mental health and parenting skills, at least in the short term

Differentiated educational strategies:

Research has focused on identifying alternative educational strategies that can be used to improve learning opportunities for children presenting with challenging behaviours from various causes. Supportive school strategies for children with EBDs have traditionally focused on classroom management, social skills and anger management, but many researchers have more recently argued that academically-focused interventions may be most effective[112]. Traditional school policies of suspending or expelling children with EBD can be harmful to them. Researchers have developed “step-by-step” guidelines for teachers to guide them in the selection and implementation of evidence-based strategies that have been identified as effective in increasing levels of engagement and achievement by children with EBD, including peer-assisted learning procedures, class-wide peer tutoring, self-management interventions and tiered intervention systems - most notably Response to Intervention (RtI) and Positive Behavioural Interventions and Supports (PBIS)[113,114].

There is increasing evidence to confirm that school-based interventions to address emerging DBPs produce significant reductions in both parent-, self- and teacher-reported internalizing and externalizing symptoms[114,115].

Treatment and Education of Autistic and Related Communication Handicapped Children (TEACCH) is an educational system designed for the management of children with Autism and related communication disorders[116,117]. There is some evidence that TEACCH programmes also lead to some improvements in motor skills and cognitive measures[117].

Best practice management strategies for children with PDA are known to differ from those with Autism. Specific guidelines for children with PDA[118] have been published by the British institute for Learning Disabilities. Educational support for CYP with PDA relies on highly individualized strategies that allows them to feel in control. They would respond much better to more indirect and negotiative approaches. For example, “I wonder how we might…” is likely to be more effective than “Now let’s get on with your work”

Child-focused psychological interventions

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is one of the most widely used non-pharmacologic treatments for individuals with emotional disorders, especially depression, and with individuals with behavioural problems including ASD[119]. CBT integrates a combination of both cognitive and behavioural learning principles to encourage desirable behaviour patterns. Research evidence from several trials[120] provide strong support for the effectiveness of cognitive–behavioural interventions among CYP with Anxiety and Depression. A recent study of child-focused CBT programme introduced at schools has shown that it produces significant improvement in disruptive behaviours among children[121].

Self-esteem building strategies can help many children with EBDs, who often experience repeated failures at school and in their interactions with others. These children could be encouraged to identify and excel in their particular talents (such as sports) to help build their self-esteem.

Behavioural modification and social communication enhancement strategies

Behavioural interventions and techniques are designed to reduce problem behaviours and teach functional alternative strategies using the basic principles of behaviour change. Most interventions are based on the principles of Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA) which is grounded on behavioural learning theory. Table 5 summarizes the common behavioural modification strategies for management of childhood EBDs.

Several strategies have been designed to help children acquire important social skills, such as how to have a conversation or play cooperatively with others, using social group settings and other platforms to teach peer interaction skills and promote socially appropriate behaviours and communication. There is ongoing research in the development of social communication treatment approaches[45]. Table 4 summarizes common social communication enhancement strategies.

Psychopharmacology of childhood behavioural and emotional disorders

Medications are often prescribed as part of a comprehensive plan for the management of childhood EBDs that includes other therapies. The greatest level of evidence for pharmacotherapy of childhood EBDs is available for their use in the management of childhood and adolescent ADHD. There is less evidence of any efficacy for medications in the management of other DBPs including ODD and CD. Table 8 lists the common classes of medications used in the management of childhood EBD.

Psychostimulants (including different formulations of Methylphenidate and Dexamphetamines) remain the primary medication of choice for management of ADHD in CYP for more than 60 years. About 75% to 80% of children with ADHD will benefit from the use of psychostimulants. Non-stimulant therapy with Atomoxetine or alpha 2-adrenergic agonists (Clonidine and Guanfacine) are also effective second-line alternative options[133]. A recent analysis of 16 randomized trials and one meta-analysis, involving 2668 participants with ADHD, showed that both stimulant and non-stimulant medications led to clinically significant reductions in core symptoms with consistently high effect sizes. The psychosocial treatments alone combining behavioural, cognitive behavioural and skills training techniques demonstrated small- to medium-sized improvements for parent-rated ADHD symptoms, co-occurring emotional or behavioural symptoms and interpersonal functioning[134].

The use of pharmacological treatments for symptoms of ASD is common but challenging, as there are no medications that directly treat the social and language impairments present in individuals with ASD. The medications used most frequently include antipsychotics (e.g., Risperidone) and Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRI) to treat mood and repetitive behaviour problems, and stimulants and other medications used to treat ADHD-related symptoms. The evidence base is good for using atypical antipsychotics to treat challenging and repetitive behaviours, but they also have significant side effects[119,135]. Naltrexone is an opioid antagonist that has been shown from a systematic review (involving 155 children from 10 studies) to significantly improve symptoms of self-injury, irritability, restlessness and hyperactivity in autistic children, with minimal side effects and generally good tolerance, although long-term data are lacking[136].

Medication use in preschool children for control of ASD and ADHD symptoms is still largely controversial. Stimulant medications for treatment of ADHD are not uniformly licensed for pre-schoolers as there is limited available research evidence to confirm efficacy and safety. Moreover, the effectiveness of parenting interventions in this age group are comparable to the effects of using stimulant drugs among the older CYP[137,138].

Research evidence from two systematic reviews and 20 randomized controlled trials has recently documented the efficacy of psychopharmacology in the management of childhood DBP. Psychostimulants have have been shown to have a moderate-to-large effect on oppositional behaviour, conduct problems, and aggression in youths with ADHD, with and without ODD or CD, while Atomoxetine has only a small effect. There is very-low-quality evidence that Clonidine and Guanfacine have a small-to-moderate effect on oppositional behaviour and conduct problems in youths with ADHD[139].

Other behavioural disorders in children could also be successfully treated by medications. Traditional and the newer atypical antipsychotics can be used for OCD, Depression, aggression and mood instability[140].

The commonest antidepressants in used in children are the SSRI and Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor (SNRI) medications as they work well and usually have fewer side effects compared to the older Tricyclic Antidepressants. Antidepressants can be used in the management of Major Depression, Anxiety, Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD), OCD, PTSD and Social Anxiety. They may also be used to treat enuresis and pre-menstrual syndrome

conclusion

Childhood EBDs have significant negative impacts on the society, in the form of direct behavioural consequences and costs, and on the individual, in the form of poor academic, occupational and psychosocial functioning and on the family. The costs to society include the trauma, disruption and psychological problems caused to the victims of crime or aggression in homes, schools and communities, together with the financial costs of services to treat the affected individuals, including youth justice services, courts, prison services, social services, foster homes, psychiatric services, accident and emergency services, alcohol and drug misuse services, in addition to unemployment and other required state benefits[23].

Prevention and management of EBD is not easy and it requires an integrated multidisciplinary effort by healthcare providers at different levels to be involved in the assessment, prevention and management of affected individuals, and also to provide social, economic and psycho-emotional support to the affected families.

There is increasing evidence base for several psychosocial interventions but less so for pharmacological treatment apart from the use of stimulants for ADHD. Preventive measures that have been researched for controlling the risk of childhood emotional and behaviour problems include breastfeeding[142], avoiding second-hand smoke exposure in non-smoker youths [143] and intensive parenting interventions

Table 8.

Major classes of medications used in management of childhood emotional and behavioural disorders

Common examples | Indications for use | Common Side-effects | Follow up monitoring | |

Traditional antipsychotics | Haloperidol, Chlorpromazine, Thiotixene, Perphenazine, Trifluoperazine | Schizophrenia, Bipolar disorder, Schizoaffective, Disorder, Obsessive-compulsive disorder, Depression, Aggression, Mood instability, Irritability in ASD | Tremors, Muscle spasms, Abnormal movements, Stiffness, Blurred vision, Constipation | Frequent blood tests (Clozapine), Blood pressure checks, Cholesterol testing, Heart Rate checks, Blood Sugar testing, Electrocardiogram, Height, Weight and blood chemistry tests |

Atypical antipsychotics | Aripiprazole, Clozapine, Olanzapine, Quetiapine, Risperidone, Ziprasidone | Low white blood cell count (Agranulocytosis - with Clozapine), Diabetes, Lipid abnormalities, Weight gain, Other medication-specific side effects | ||

Tricyclic antidepressants | Amytriptyline, Desipramine, Doxepin, Imipramine, Nortriptyline, | Depression, Anxiety, Seasonal Affective Disorder, OCD, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Social Anxiety, Bed-wetting and pre-menstrual syndrome | Dry mouth, Constipation, Blurry vision, Urinary retention, Dizziness, Drowsiness | Watch for worsening of depression and thoughts about suicide, Watch for unusual bruises, bleeding from the gums when brushing teeth, especially if taking other medications, Blood tests and Blood pressure checks may be needed |

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors | Citalopram, Escitalopram, Fluoxetine, Fluvoxamine, Sertraline | Headache, Nervousness, Nausea Insomnia, Weight Loss | ||

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor | Venlafaxine, Levomilnacipran, Duloxetine, Desvenlafaxine | |||

Other antidepressants | Bupropion, Mirtazepine, Trazodone | |||

Stimulants | Methylphenidate Immediate Release and Modified Release (e.g., Concerta XL, Equasym XL), Dexamfetamines Immediate Release and Modified Release (e.g., Lisdexamfetamine) | ADHD | Decreased appetite/ weight loss, Sleep problems, Jitteriness, restless, Headaches, Dry mouth, Dysphoria, feeling sad, Anxiety, Increased heart rate, Dizziness | Blood pressure and heart rate will be checked before treatment and periodically during treatment. Child’s height and weight are monitored |

Non-stimulants | Atomoxetine | |||

Alpha-2 agonists | Clonidine, Guanfacine | Drowsiness, Dizziness, Sleepiness | ||

Benzodiazepines | Lorazepam, Clonazepam, Diazepam, Alprazolam, Oxazepam, Chlordiazepoxide | Anxiety, Panic disorder, Alcohol withdrawal, PTSD, OCD | Drowsiness, Dizziness, Sleepiness, Confusion, Memory loss, Blurry vision, Balance problems, Worsening behaviour | Do not stop these medications suddenly without slowly reducing (tapering) the dose as directed by the clinician. While taking buspirone, avoid grapefruit juice, Avoid alcohol, Blood tests may be needed prior to the start of treatment and during treatment |

Antihistamines | Hydroxyzine HCl, Hydroxyzine, Pamoate, Alimemazine | Sleepiness, Drowsiness, Dizziness, Dry mouth, Confusion, Blurred Vision, Balance problems, Heartburn | ||

Other anxiolytics | Buspirone | Dizziness, Nausea, Headache, Lightheadedness, Nervousness | ||

Sleep-enhancement | Zolpidem, Zaleplon, Diphenhydramine, Trazodone | Insomnia (short-term) | Headache, Dizziness, Weakness, Nausea, Memory loss, Daytime sleepiness, Hallucinations, Dry mouth, Confusion, Blurred Vision, Balance problems, Heartburn | Blood tests may be needed before the start of treatment. Avoid alcohol |