(UNIT 5) Chapter 12 - The cell Cycle

1/40

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

41 Terms

Cell division

Reproduction of cells

Key Roles of Cell Division

Asexual reproduction in prokaryotic cells.

Multicellular eukaryote’s cell division starts from a fertilized egg.

Cell division helps in growth and repair

Genome

A cell’s DNA

Prokaryotic VS Bacteria VS Eukaryotic Cells’s DNA

Prokaryotic: Single, linear, DNA molecule associated with many proteins (maintain structure of chromosomes and help control activity of genes). Carries several hundred genes (units of information that specify an organism’s inherited traits.)

Bacteria have one single circular molecule, along with proteins and RNA molecules (nucleoid).

Plasmid DNA: can be picked up from other bacterial cells through conjugation or the environment. This contains few genes that might allow the bacteria to overcome stressful situations.

Eukaryotic: A number of linear DNA molecules and the length is enormous.

Chromatin

The entire complex of DNA and proteins. Organized into long thin fiber.

Chromosomes & structure

DNA molecules packaged together.

Double helix DNA molecule

Associated proteins = Histone proteins

Nucleosome

A segment of DNA wrapped around 8 histone proteins. (Beads on a string.)

Human somatic cells VS Reproductive Cells

Human somatic cells (all body cells except reproductive cells) contain 46 chromosomes, made up to two sets of 23, one inherited from each parent.

Reproductive cells (gametes, sperm/eggs) have half (23) as many chromosomes as somatic cells.

Diploid

Cell that contains two sets of homologous chromosomes. Example, somatic cells.

Homologous Chromosomes

Chromosomes containing the same type of genetic information. One comes from male parent, one comes from a female parent.

Autosomes & Sex Chromosome

Autosomes: First 22 pairs of homologous chromosomes.

Sex chromosome: 23rd pair (XX is female, XY is male).

Haploid

Cell that contains one set of chromosomes. Example, gametes.

DNA shape after and before replication

When not dividing (or replicating DNA) each chromosome is in the form of a long chromatin fiber. After DNA replication, the chromosomes condense.

Each chromatin fiber becomes densely coiled and folded, making the chromosomes much shorter and so thick that we can see them with a light microscope.

Sister chromatids & structure

Duplicated chromosomes consist of two, joined copies of the original chromosome containing identical DNA molecules are attached all along their lengths by protein complexes called cohesins (sister chromatid cohesion).

Centromere: A region made of repetitive sequences in the chromosomal DNA where the chromatid is attached most closely to its sister chromatid (the “waist” , inner curve, of sister chromatids).

Telomeres = repeated sequence at end of each arm

p= short arm; q= long arm

Mediated by proteins that recognize and bind to the centromeric DNA; other bound proteins condense the DNA.

Arm of chromatid: Portion of chromatid to either side of the centromere.

Meiosis & Fertilization

Produce gametes, yields daughter cells with only one set of chromosomes (half, 23). In humans it only occurs in special cells in ovaries or testes.

Fertilization: Fuses two gametes together (creating 46 again). Then mitosis occurs. (Occurs when sperm meets egg and creates zygote.)

Cell Cycle

Life of a cell from the time it is first formed during division of a parent cell until its own division into two daughter cells.

Phases of cell cycle

Interphase: 90% of cell cycle, cell grows by producing proteins and organelles.

G1 phase (“first gap”): Metabolic activity and cell growth. 5-6 hours

Cells that don't divide often spend their time in G1 or G0.

S phase (“synthesis”): Metabolic activity, growth, and DNA synthesis (duplication). 10 -12 hours

G2 phase (“second gap”): Metabolic activity, growth, and preparation for cell division. 4-6 hours

Mitotic (M) phase: Includes both mitosis and cytokinesis, usually shortest. 1 hour

Mitosis: Distribution of chromosomes into two daughter nuclei. (Nucleus divides.)

Cytokinesis: Division of cytoplasm, producing two daughter cells.

Mitosis Stages

G2 of Interphase

Two centrosomes have formed by duplication of a single centrosome.

Chromosomes are duplicated and uncondensed.

Contains nucleoli.

Prophase

The chromatin fibers become more tightly coiled, condensing into discrete chromosomes becoming visible.

Nucleoli disappear.

Duplicated chromosomes appear as two sister chromatids then resulting in sister chromatid cohesion.

The mitotic spindle (between two centrosomes) begins to form as centrosomes move away from each other.

Asters (“stars”): Radial array of shorter microtubules that extend from centrosomes.

Prometaphase

Nuclear envelope fragments.

Microtubules extending from each centrosome now invade the nuclear area.

A kinetochore, specialized protein structure, has formed at the centromere of each chromatid.

Some microtubules attached to kinetochores (kinetochore microtubules) jerk the chromosomes back and forth.

Nonkinetochore microtubules interact with those from the opposite pole of the spindle, lengthening the cell.

Metaphase

The centrosomes are at opposite poles of the cell.

The chromosomes are at the metaphase, a (imaginary) plane that is equidistant between the spindle's two poles.

The kinetochores of the sister chromatids are attached to kinetochore microtubulus coming from opposite poles.

Anaphase

Shortest stage.

Begins when cohesin proteins are cleaved (split) by an enzyme called separase, the two sister chromatids part becoming an independent chromosome.

The chromosomes begin moving toward opposite ends (kinetochore microtubulus shorten).

The cell elongates as nonkinetochore microtubules lengthen.

Telophase

Two daughter nuclei form in the cell. Nuclear envelopes arise from the fragments of the parent cell’s nuclear envelope and other portions of the endomembrane system.

Nucleoli reappear.

Chromosomes become less condensed.

Remaining spindle microtubules are depolymerized.

Cytokinesis

Division of the cytoplasm is well under way by late telophase.

In animal cells, cytokinesis involves the formation of a cleavage furrow, which pinches the cell in two.

In plant cells, cell plate forms.

What is mitotic spindle made of?

Fibers made of microtubules and associated proteins.

When a mitotic spindle assembles, other microtubules of the cytoskeleton partially disassemble, providing material used to construct it.

The spindle microtubules elongate (polymerize) by incorporating more subunits of the protein tubulin and shorten (depolymerize) by losing subunits.

Mitotic spindle in animal cells

During interphase (animal cells), the single centrosome duplicates.

One side of the chromosome begins to move toward the pole due to being held by kinetochore microtubules however this is halted when the other side also gets captured by a kinetochore microtubules leading to a “draw” and thus the chromosomes lining in the middle.

Microtubules that do not attach to kinetochores have been elongating the cell, and by metaphase they overlap and interact with other nonkinetochore microtubules from the opposite pole of the spindle.

In a dividing animal cell, the nonkinetochore microtubules are responsible for elongating the whole cell during anaphase.

By metaphase, the microtubules of the asters have also grown and are in contact with the plasma membrane. The spindle is now complete.

Poleward movement of chromosomes occurs

As the microtubules push apart from each other, their spindle poles are pushed apart, elongating the cell.

At the same time, the microtubules lengthen somewhat by the addition of tubulin subunits to their overlapping ends. As a result, the microtubules continue to overlap.

How does poleward movement of chromosomes happen?

Motor proteins on the kinetochores “walk” the chromosomes along the microtubules, which depolymerize at their kinetochore ends after the motor proteins have passed. (“Pac Man”)

Chromosomes are “reeled in” by motor proteins at the spindle poles and that the microtubules depolymerize after they pass by these motor proteins at the poles.

Cytokinesis in animal cells

Cytokinesis, in animal cells, occurs by a process known as cleavage.

The first sign of cleavage is the appearance of a cleavage furrow, a shallow groove in the cell surface near the old metaphase plate.

On the cytoplasmic side of the furrow is a contractile ring of actin microfilaments associated with molecules of protein myosin. The actin microfilaments interact with the myosin molecules, causing the ring to contract (go inward) eventually deepening and producing two cells.

Cytokinesis in plant cells

Cytokinesis, in plant cells, during telophase, vesicles derived from the Golgi apparatus move along microtubules to the middle of the cell, where they come together, producing a cell plate.

Cell wall materials carried in the vesicles collect inside the cell plate as it grows.

The cell plate enlarges until its surrounding membrane fuses with the plasma membrane along the perimeter of the cell, producing two cells.

Meanwhile, a new cell wall arising from the contents of the cell plate forms between the daughter cells.

Binary Fission

Binary fission: Asexual reproduction of single-celled eukaryotes or reproduction in prokaryotes in which the cell grows roughly double its size then divides to form two cells.

The process in eukaryotes involves mitosis, while that in prokaryotes does not.

The DNA (bacterical chromosome) begins to replicate at a specific place (origin of replication), producing two origins.

Eventually one origin (duplicated DNA) moves rapidly toward the opposite end of the cell involving an actin-like protein.

The cell elongates while the chromosome is replicating.

When replication is complete, proteins cause its plasma membrane to pinch inward by a tubulin-like protein, dividing the parent bacterial cell into two daughter cells.

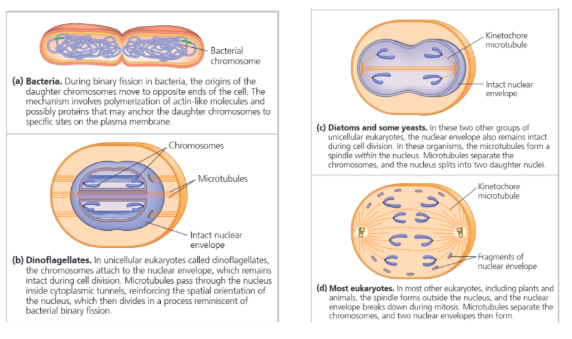

The Evolution of Mitosis

Proteins involved in bacterial binary fission are related to eukaryotic proteins that function in mitosis.

Two unusual types of nuclear division that keep the nuclear envelope intact.

Cell cycle control system

Cyclically operating set of molecules (signaling molecules in the cytoplasm) that both triggers and coordinates key events in the cell cycle.

Checkpoint

Control point where stop and go-ahead signals can regulate the cycle.

The cell cycle is regulated at certain checkpoints for both internal and external signals.

Signals registered at checkpoints and report if certain important processes have occurred. The signals are transmitted within the cell by signal transduction pathways

Internal regulatory molecules

Mainly proteins of two types: protein kinases and cyclins.

Many of the kinases are present at a constant concentration but usually in an inactive form. To be active it must be attached to a cyclin (protein, gets its name from its cyclically fluctuating concentration.)

These kinases are called cyclin-dependent kinases (protein enzyme, Cdks). Cdks are dependent on cyclic concentration.

During G2 when Cdk associates with cyclin it phosphorylates a variety of proteins, initiating mitosis.

Helps control all stages of cell cycle and gives go-ahead signals at some checkpoints.

Example of Cdk

MPF (“M-phase-promoting factor”): Cyclin-Cdk complex that was discovered first (in frog eggs).

MPF acts both directly as a kinase and indirectly by activating other kinases. For example, MPF causes phosphorylation of various proteins of the nuclear lamina which promotes fragmentation of the nuclear envelope during prometaphase of mitosis.

There is also evidence that MPF contributes to molecular events required for chromosome condensation and spindle formation during prophase.

During anaphase, MPF switches itself off by initiating a process that leads to the destruction of its own cyclin.

Three Main Checkpoints + Additional

Three checkpoints in G1 (⅘ to the end), G2 (end of) and mitosis (⅔ to the end).

G1: Most important phase, if a cell receives a go-ahead signal here it will usually complete the whole cell cycle. If it doesn't it may exit the cycle and switch to G0 phase (nondividing state).

Controlled by cell size, growth factors, environment (lets say a cell doesn’t have multiple copies of a certain DNA).

Cells in the G0 phase include mature nerve cells and muscle cells. Liver cells can be called back from the G0 phase by external cues (growth factors) from injury.

G2 checkpoint

Controlled by DNA replication completion, DNA mutations, cell size

M checkpoint: (Internal signal): Ensures daughter cells do not end up with missing or extra chromosomes.

Receives a stop single when any of its chromosomes are not properly attached to the spindle fibers (not beginning anaphase.) When done, the appropriate regulatory protein complex becomes activated (complex made up of several proteins).

Once activated, the complex sets off a chain of molecular events that activates the enzyme separase (cleaves the cohesins).

Additional checkpoint

Checkpoint in S phase: Stops cells with DNA damage from proceeding in the cell cycle.

Checkpoint between anaphase and telophase: Ensures anaphase is completed and the chromosomes are well separated before cytokinesis can begin, thus avoiding chromosomal damage.

Stop and go-ahead signals

Signaling molecules

If an essential nutrient is lacking it fails to divide.

Has specific growth factors.

Growth factor: Protein released by certain cells that stimulates other cells to divide.

Density-dependent inhibition: Effect of an external physical factor on cell division.

External Regulatory Factors

Density-dependent inhibition Cells normally divide until they form a single layer of cells on the inner surface of a culture. If cells are removed they begin dividing to fill up the open space again.

Cell-surface protein binds to adjoining cells to inhibit growth.

Anchorage dependence: To divide, they must be attached to something.

Anchorage is signaled to the cell cycle control system via pathways involving plasma membrane proteins and elements of the cytoskeleton linked to them.

Cancer Cells vs Normal Cells (Regulation)

Cancer cells do not stop dividing even when growth factors are depleted. (Can respond to regulation signals.)

Explanations:

Cancer cells do not need growth factors in their culture medium to grow and divide. They may make a required growth factor themselves, or have an abnormality in the signaling pathway that conveys the growth factor’s signal to the cell cycle control system even in absence of it.

Abnormal cell cycle control system: Change in one or more genes (mutation) that alters the function of their protein products, resulting in faulty cell cycle control.

Cancer cells stop dividing at random points in the cycle, rather than at normal checkpoints.

Cancer cells can go on dividing indefinitely in culture if they are given a continual supply of nutrients (“immortal”).

Cancer cells evade the normal controls that trigger a cell to undergo apoptosis when something is wrong (mistake in DNA replication).

Abnormal changes on cell surface cause them to lose attachments to neighboring cells and the extracellular matrix, allowing them to spread into nearby tissues.

Transformation

A process that cells in culture that have the ability to divide indefinitely undergo.

Multistep process of about 5-7 genetic changes (for a human) for a cell to transform.

Example of immortal cancer cells

Example: HeLa cells (tumor removed from Henrietta Lacks) which were deemed immortal (could survive outside the body) helped biologists make countless significant discoveries over the years.

Imporant tumor suppressor protein vs what happens to it in cancer cells

P53 is an important tumour-suppressor protein that is altered in most cancers. p53 activates various responses, including cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis. Each of these appears to contribute to tumour suppression.

Cell cycle arrest → DNA repair → cell cycle restart , apoptosis

Mutated cell: Cell cycle continues despite problems.

How does cancer cells form?

A single cell in a tissue undergoes the first of many steps that convert a normal cell to a cancer cell.

This cell often has altered proteins on its surface and the immune system may destroy it but if not it spreads.

It will proliferate and form a tumor (mass of abnormal cells within normal tissue).

Two types of tumors

Benign Tumor: The cells remain at the original site as their genetic and cellular changes don’t allow them to move to or survive at another site.

Don’t cause serious problems and can be removed by surgery.

Malignant Tumor: Cells who can spread to new tissues and impair the functions of one or more organs (cancer).

May also secrete signaling molecules that cause blood vessels to grow toward the tumor and separate from the original tumor, enter blood vessels and lymph vessels, and travel to other parts of the body.

Metastasis

Spread of cancer cells to locations distant from their original site.

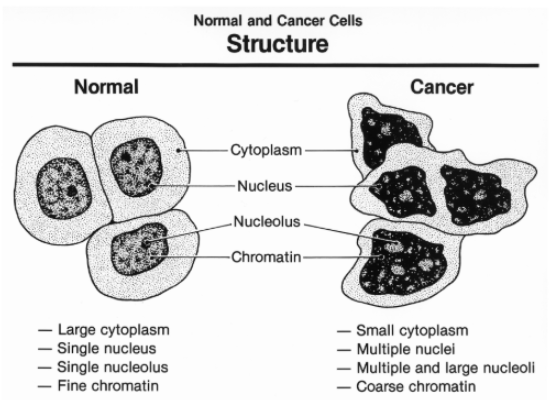

Normal cell vs Cancer cell (structure)

These cancer cells may have unusual numbers of chromosomes, alter metabolism, and fail to function in any constructive way.

Cancer Treatments

Localized: High energy radiation, which damages DNA in cancer cells (much more than normal cells). Cancer cells lose the ability to repair DNA.

Known/suspected metastatic tumors: Chemotherapy, drugs that are toxic to actively dividing cells are used through the circulatory system.

Chemotherapeutic drugs interfere with specific steps in the cell cycle. For example, the drug Taxol freezes the mitotic spindle by preventing microtubule depolymerization, which stops actively dividing cells from proceeding past metaphase and leads to their destruction.

Side effects (like hair loss, nausea, infection) are due to effects of the drugs on normal cells that divide frequently.