week 3; atypical development: diagnosis

1/31

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

32 Terms

Diagnosing William’s syndrome

physical and cognitive features

more sunken nasal bridge, gaps in teeth, all prominent, but if not prominent when younger may test cognitive profile

confirmed with a genetic test

blood test to identify absence of the ELN (elastin) gene, if absent they may have William’s Syndrome

the laboratory test used to detect the elastin gene is called fluorescent in situ hybridilization (FISH)

Down syndrome: prenatal

Screening test available between 10-14 weeks of pregnancy - Typically carried out at the 12 week scan

‘Combined’ test- has two primary parts

Blood test (Mother’s blood contains DNA from the foetus)

Nuchal translucency scan (checks the build of fluid at the back of the baby’s neck, the larger it is the greater the chance of a chromosomal abnormality)

If this test shows a ‘high risk’ then the mother would be offered an amniocentesis to confirm

Take a sample of the amniotic fluid

Voluntary

Down syndrome: post natal

check physical characteristics

takes a while for features to take shape often, so may not be picked up on immediately

if unclear, follow up with a blood test

check for the presence of an extra chromosome

Conditions trickier to diagnose than WS and DS

ADHD

autism

Comorbidity- AHD and Autism

comorbidity rates potentially as high as 70%,

The DSM-4 (2000) prohibited dual diagnosis of autism and ADHD, But is listed as two separate conditions in the DSM-5

Diagnosing ADHD

Initial referral often made in school (e.g. by SENCO).

Primary Care

GP / Social worker / Educational Psychologist

Secondary Care

Psychiatrist / Psychologist working within CAMHS.

Diagnosis based on:

Discussion about behaviour in a different settings (e.g. school, home, etc)

Full developmental and psychiatric history and observer reports

Assessment of their mental state.

Screening instruments can be used to supplement diagnosis (but not on their own).

Conner’s rating scales

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

Diagnosing ASC

Initial referral often made by parents / school / GP.

Referral made to secondary care (e.g. CAMHS)

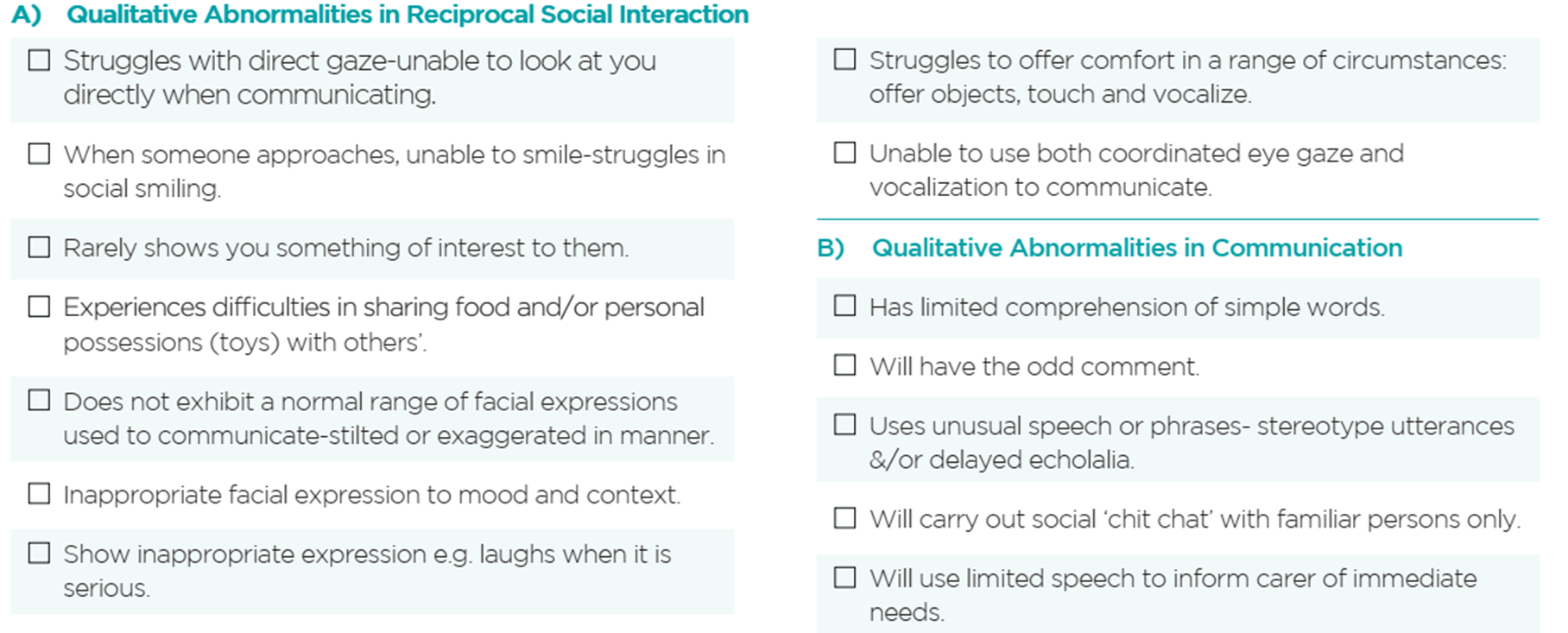

Autism assessment:

detailed questions about parent's or carer's concerns and, if appropriate, the young person's concerns

details of the child's or young person's experiences of home life, education and social care, a developmental history, focusing on developmental and behavioural features consistent with ICD-10 or DSM-5 criteria

a medical history, including prenatal, perinatal and family history, and past and current health conditions

a physical examination

Diagnostic manuals

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (currently 5th Edition, DSM-V, published in 2013)

International Classification of Diseases (currently 11th Edition, ICD-11)

diagnostic manual for ADHD- inattention

Inattention: 6 symptoms of inattention for children up to age 16 years, or 5 for ages 17 years and adults; symptoms present for at least 6 months:

Often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, at work, or with other activities.

Often has trouble holding attention on tasks or play activities.

Often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly.

Often does not follow through on instructions and fails to finish task (e.g., loses focus, side-tracked).

Often has trouble organizing tasks and activities.

Often avoids, dislikes, or is reluctant to do tasks that require mental effort over a long period of time (such as schoolwork or homework).

Often loses things necessary for tasks and activities (e.g. school materials, pencils, books, tools, wallets, keys, paperwork, eyeglasses, mobile telephones).

Is often easily distracted

Is often forgetful in daily activities.

diagnostic manual for ADHD- Hyperactivity and impulsivity

6 symptoms for children up to age 16 years, or 5 for adolescents age 17 and older; symptoms have been present for at least 6 months and is disruptive and inappropriate for the person’s developmental level:

Often fidgets with or taps hands or feet, or squirms in seat.

Often leaves seat in situations when remaining seated is expected.

Often runs about or climbs in situations where it is not appropriate (adolescents or adults may be limited to feeling restless).

Often unable to play or take part in leisure activities quietly.

Is often “on the go” acting as if “driven by a motor”.

Often talks excessively.

Often blurts out an answer before a question has been completed.

Often has trouble waiting their turn.

Often interrupts or intrudes on others (e.g., butts into conversations or games)

DSM-5: Criteria for autism- Persistent deficits

Persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts (You need to have all of these to be diagnosed):

Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, ranging, for example, from abnormal social approach and failure of normal back-and-forth conversation; to reduced sharing of interests, emotions, or affect; to failure to initiate or respond to social interactions.

Deficits in nonverbal communicative behaviours used for social interaction, ranging, for example, from poorly integrated verbal and nonverbal communication; to abnormalities in eye contact and body language or deficits in understanding and use of gestures; to a total lack of facial expressions and nonverbal communication.

Deficits in developing, maintaining, and understand relationships, ranging, for example, from difficulties adjusting behaviour to suit various social contexts; to difficulties in sharing imaginative play or in making friends; to absence of interest in peers.

DSM-5: criteria for ASC: restricted and repetitive behaviours

Restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities, as manifested by at least two of the following, currently or by history:

Stereotyped or repetitive motor movements, use of objects, or speech (e.g., simple motor stereotypes, lining up toys or flipping objects, echolalia, idiosyncratic phrases).

Insistence on sameness, inflexible adherence to routines, or ritualized patterns of verbal or nonverbal behaviour (e.g., extreme distress at small changes, difficulties with transitions, rigid thinking patterns, greeting rituals, need to take same route or eat same food every day).

Highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus (e.g., strong attachment to or preoccupation with unusual objects, excessively circumscribed or perseverative interests).

Hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input or unusual interest in sensory aspects of the environment (e.g. apparent indifference to pain/temperature, adverse response to specific sounds or textures, excessive smelling or touching of objects, visual fascination with lights or movement).

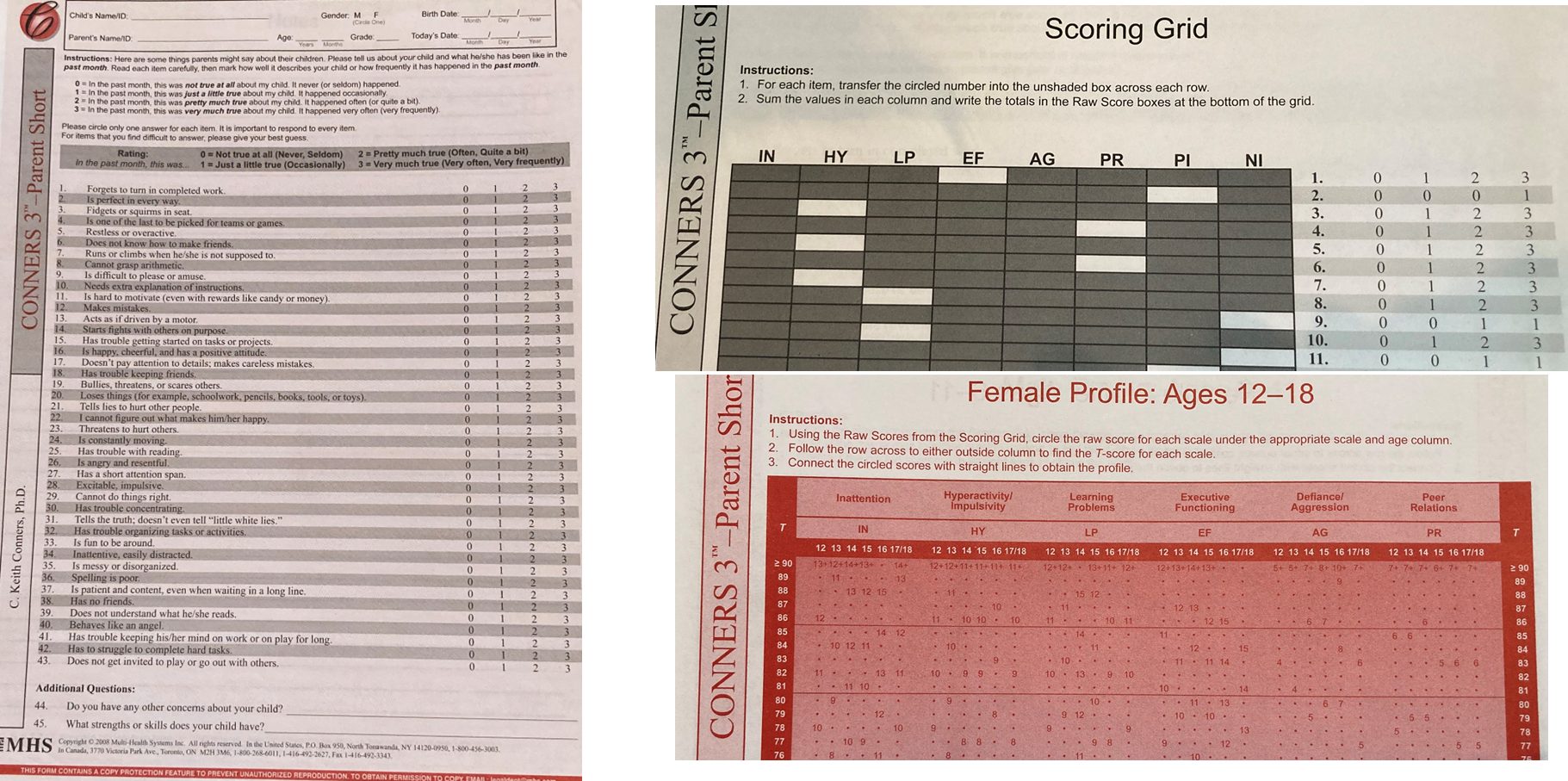

Standardised tools used in the diagnosis of ADHD

CONNERS SCALE FOR ASSESSING ADHD

Questionnaire screening for behaviours associated with ADHD, used as initial evaluation when ADHD is suspected

Three forms:

One for parents

One for teachers

Self-report to be completed by the child

Can be used during follow-up appointments to help doctors and parents monitor how well certain medications or behaviour-modification techniques are working.

The Conners Scale

43 questions in total

The psychologist will total the scores from each area of the test. They will assign the raw scores to the correct age group column within each scale. The scores are then converted to standardized scores, known as T-scores.

Standardised tools used in the diagnosis of ASC- ADOS

AUTISM DIAGNOSTIC OBSERVATIONAL SCHEDULE (ADOS)

Semi- Structured Interview. Code interaction for presence / absence of certain key behaviours, e.g. eye-contact, reciprocal interaction, turn-taking, imaginative play, non-verbal communication.

Five modules

Toddler: 12 – 30 months (no consistent speech)

Module 1: 31 months + (no consistent speech)

Module 2: Children any age (not verbally fluent)

Module 3: Children & young adolescents (verbally fluent)

Module 4: older adolescents & adults (verbally fluent)

ADOS:

each behaviour has its own code

you add certain codes together to get an overall score for each domain of the DSM-5 Criteria

the pp’s scare on the two domains determines if they would be classed as autistic

Standardised tools used in the diagnosis of ASC- ADI

AUTISM DIAGNOSTIC INVENTORY (ADI)

Parent / caregiver interview focusing on developmental milestones and social behaviour.

Focus on age 4 / 5

•Both of these instruments require formal training before use.

Example questions from the ADI

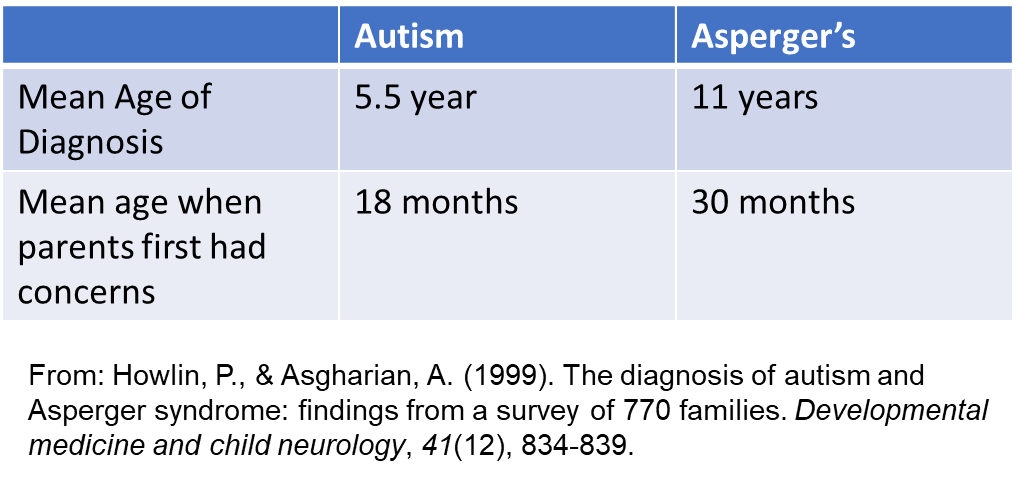

How early can ASC be diagnosed?

Based on 614 parents of children with autism and 158 children with Asperger’s syndrome.

ASC is rarely diagnosed before two years, especially in the UK.

Some countries carry out ASC screening, and the youngest age of diagnosis is 2 years old.

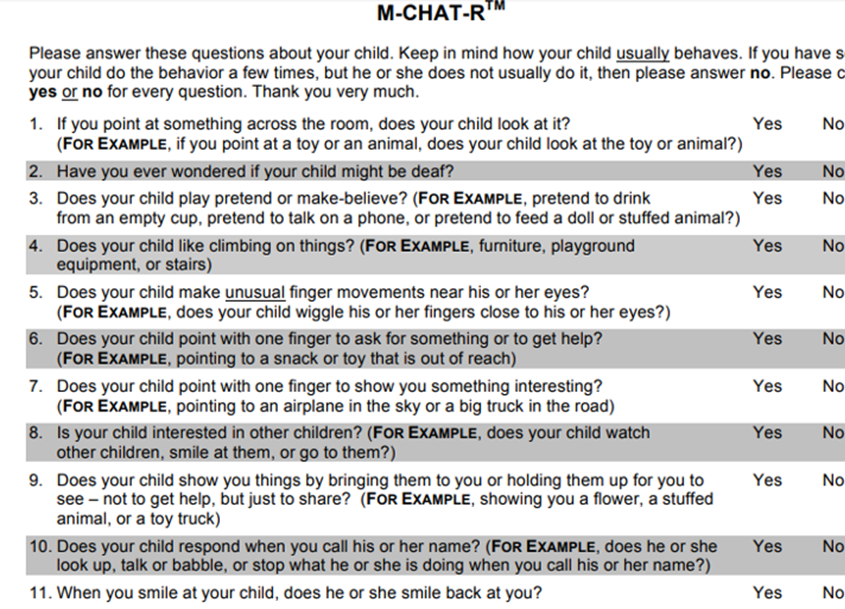

ASC Screening: the M-CHAT

A questionnaire used for screening toddlers for ASC is the M-CHAT (modified checklist for autism in toddlers).

This has been useful in children 16-36 months for flagging issues in development.

In a study, children who screened positive on the M-CHAT were 114 times more likely to receive an ASC diagnosis.

However, while the M-CHAT is useful for screening for possible “red-flags” in development, it is not particularly sensitive for detecting ONLY autism.

It also picks up cases on developmental delays, but not necessarily ASC.

For this reason, researchers who are aiming to develop tools for early-identification of ASC, have started to study the “infant-siblings” of older children with a diagnosis of ASC.

“Infant Siblings Approach”

ASC diagnosis is typically at 4 years old.

Because of the genetic association with ASC, there is an increased chance (1 in 5) that a child with an older sibling with ASC will also go on to be diagnosed with ASC.

Therefore, looking for early markers for ASC in these children is considered a fruitful approach.

Techniques for early detection

The methodologies used in the infants'-sibs approach

Functional Near Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS)

Electroencephalogram (EEG)

Eye-tracking

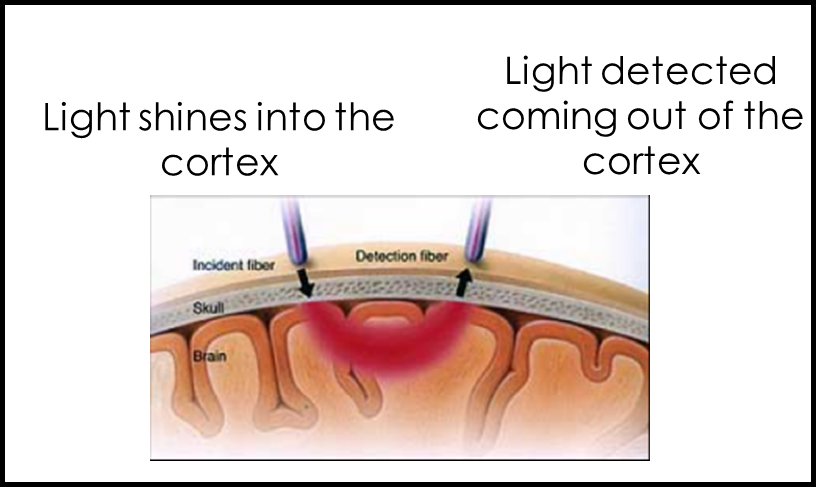

Functional Near Infrared Spectroscopy

Optical Imaging Method (like a fit-bit measuring your heart-beat).

Shine light in, measure light coming out. Light that doesn’t exit the cortex has been absorbed.

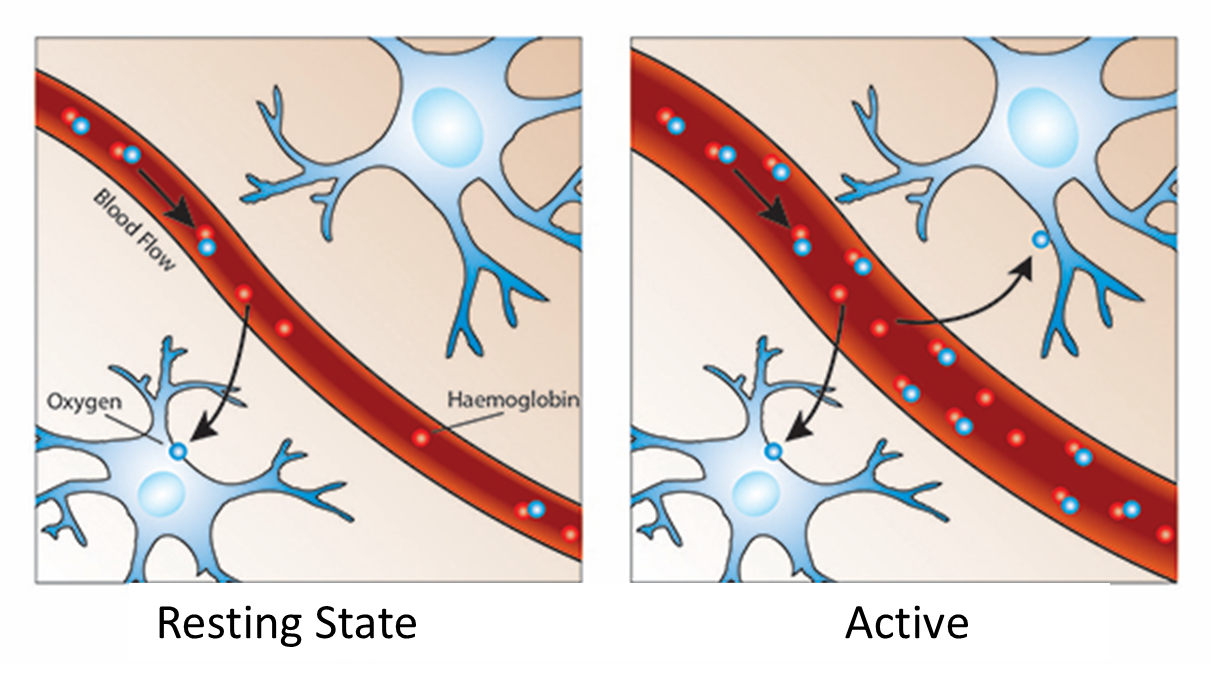

The main absorber of near-infrared light is haemoglobin. Therefore this measures haemoglobin and tell us about blood flow.

oxygen is delivered to neurons by haemoglobin in capillary red blood cells

more haemoglobin present in areas of the brain when it needs to replenish the oxygen used by active neurons

Using fNIRS to investigate early-markers of ASC

Recruited infants 4-6 months old:

Infant siblings of an older child with ASC (increased chance of ASC)

Infant siblings of an older child without ASC (lower chance of ASC)

Showed videos of social and non-social stimuli.

The infants with a higher chance of having ASC were found to show reduced activity over temporal cortex in response to social stimuli.

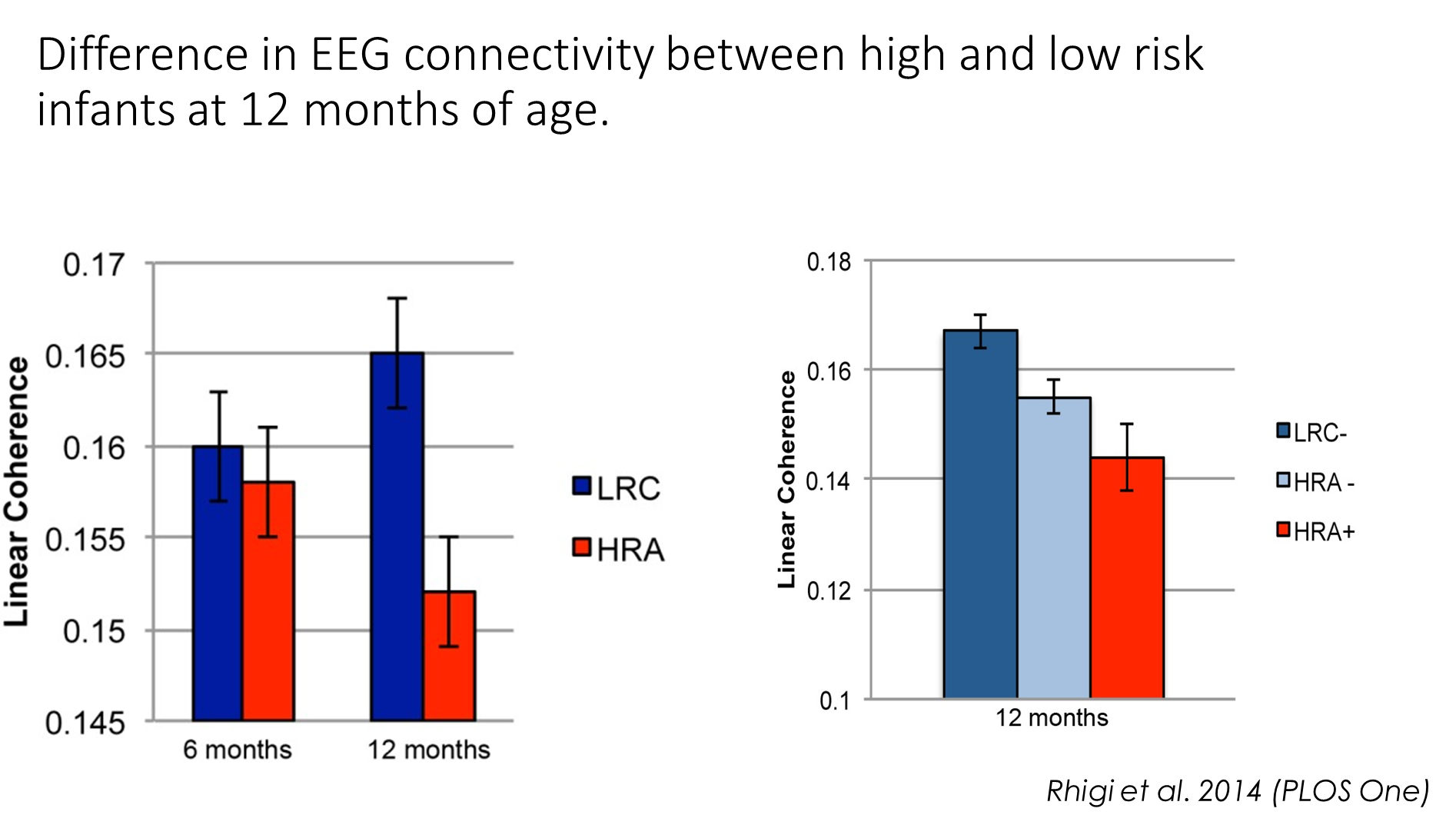

Early diagnosis of ASC- EEG and eye tracking

EEG measures electrical signals generated by the brain through electrodes placed at the scalp

EEG signals are produced by cortical field activity and are measured as changes in voltage, recorded at the scalp, over time.

EEG data can be analysed in different ways- connectivity between different brain regions (coherence)

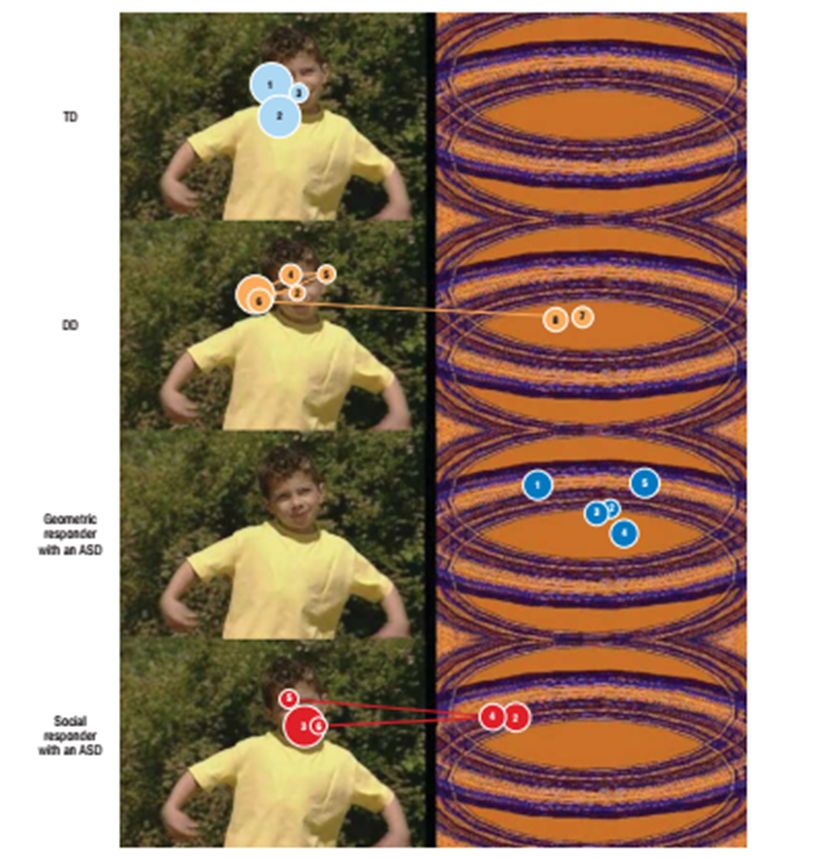

Eye tracking:

Difference in looking behaviour (measured with eye-trackers) in toddlers with a diagnosis of ASC.

Majority of neurotypical toddlers spent more time looking at the social videos than the geometric patterns.

Some toddlers with ASC spent more time looking at the geometric videos.

“If a toddler spent more than 69% of their time fixating on geometric patterns, then the positive predictive value for accurately classifying that toddler as having an ASD was 100%.”

Challenges of the infant-sibs/ early detection approach

While differences are seen at a group-level, there are not yet useful biomarkers at an individual level.

Most studies do not follow up the ‘at-risk’ infants to confirm whether they receive a later ASC diagnosis.

Therefore, group differences between high and low risk infants could reflect the “broader autism phenotype” rather than specific biomarkers for autism.

ASC is a very heterogeneous condition, with a lot of individual variability in its expression. Therefore, aiming for a single neural or behavioural construct that can classify ASC is difficult.

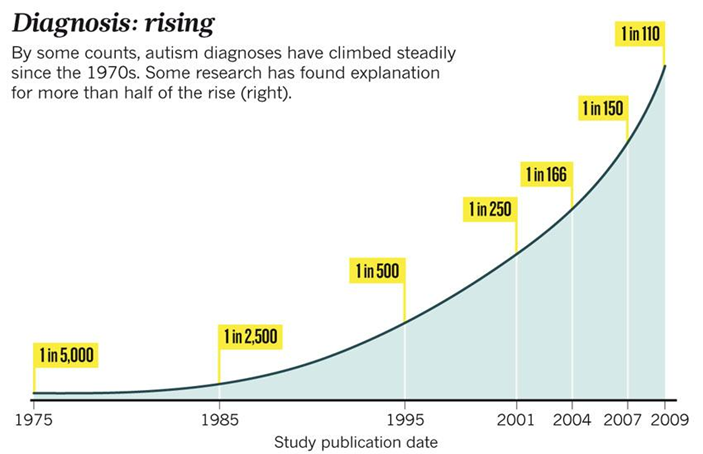

Prevalence of ADHD and ASC

Both ADHD and ASC diagnoses have increased over time

Bugha et al., 2011 –7,461 households completed an autism screening questionnaire

5,102 people eligible for phase two (AQ20 score >5)

Phase 2 = Face to face diagnostic evaluation

Number of people meeting diagnostic criteria for autism = 9.8 per 1,000 (~1 in 100)

Prevalence of diagnosed ASC

According to the Centre for Disease Control (US), ASC prevalence rates in 8 year old children are:

2008 = 1 in 88

2010 = 1 in 68

2012 = 1 in 69

2014 = 1 in 58

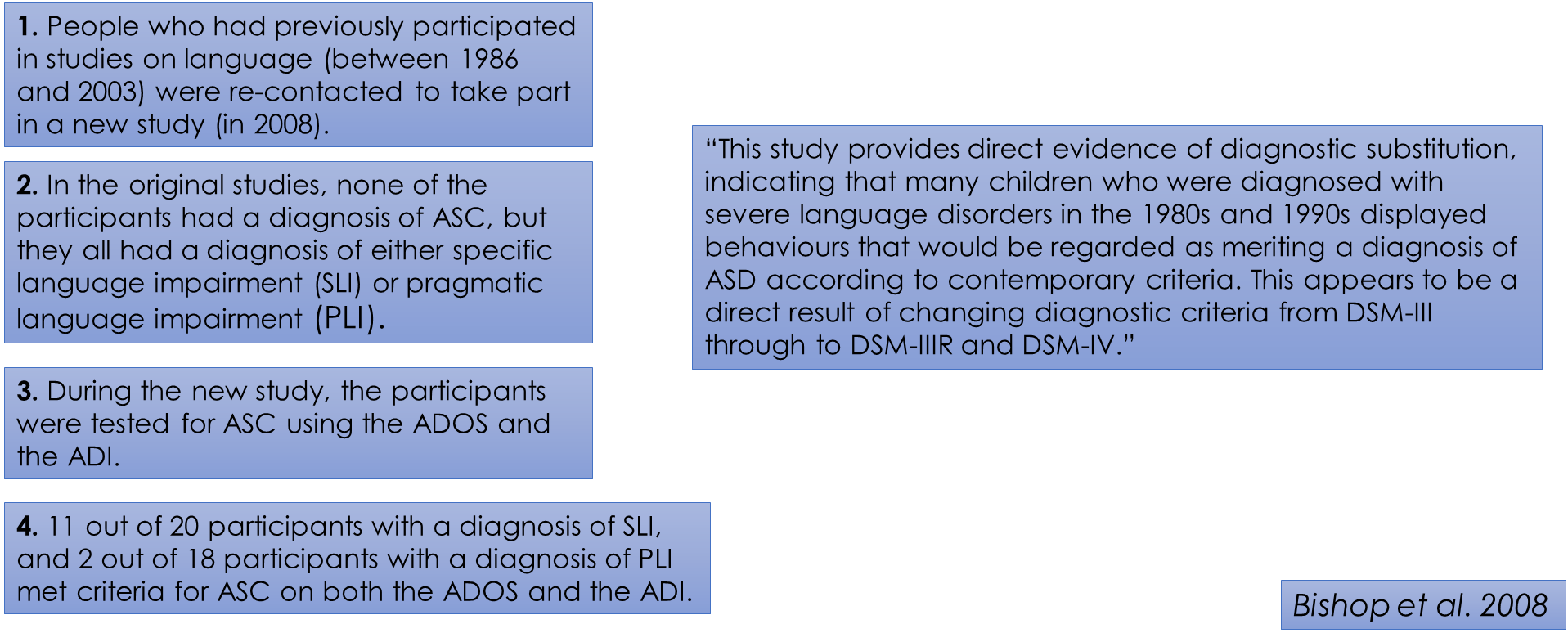

Diagnostic substitution

Children who would now meet the diagnostic criteria for ASC, were previously diagnosed with other conditions, e.g. language disorders.

Reading- intro

38 adults (15–31y; 31 males, 7 females) who had participated in studies of developmental language disorder during childhood were given the ADOS – Generic. Their parents completed the ADI – Revised, which relies on symptoms at age 4-5 years to diagnose autism.

8 individuals met criteria for autism on both instruments, and a further 4 met criteria for milder forms of ASD.

Diagnosis of autism have risen markedly over the past 3 decades. According to the ‘autism epidemic’ hypothesis, the rise is genuine, whereas the ‘diagnostic substitution’ hypothesis believes the true prevalence is constant but the diagnostic boundaries have broadened, so more children who previously had some other diagnosis are now identified with autism.

Developmental language disorder is where diagnostic substitution seems plausible, given that: (1) communication problems are a core feature of autism; (2) there was debate over diagnostic boundaries between autism and language disorder; and (3) autism is increasingly being recognized in children with normal IQ.

Reading- method- participants

Participants were drawn from a pool of children who had taken part in a series of studies of developmental language disorder conducted in the period 1986 to 2003. Autism was an exclusionary criterion in the study. Also excluded were children who had a known cause for their language impairment, such as brain injury, a known syndrome, or physical abnormality of the articulators.

We expected the subtype of language disorder to be important, given the long-standing debate between autistic disorder and pragmatic language impairment (PLI). Recruitment had focused on individuals with PLI, so the proportions with this language profile are higher than expected in this population; about 10% of children enrolled in special language classes in the UK had this profile.

Reading- Autism Diagnostic assessments in adulthood

Participants were given the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule – Generic by a trained examiner (AW or EL) and their parents were given the Autism Diagnostic Interview – Revised (ADI-R).

Together, this provided the ‘criterion standard’ for autism diagnosis, with the ADOS-G providing information about diagnostic symptomatology, and the ADI-R providing information about early development, with a focus on behaviour at 4-5 years.

The ADOS-G provides cut offs for PDNOS; the milder variant of autism, commonly referred to as ASD. On the ADI-R we coded participants above threshold for 2 of the 3 domains (communication, socialization, and repetitive behaviour) as meeting criteria for ASD.

The 31 males and 7 females were 15-31 at follow-up.

Reading- results

The association between language subgroup and diagnosis from parental report on ADI-R was statistically significant.

The association between language sub group and diagnosis was significant when ADOS-G was used.

If a strict definition of autism was used, requiring scores above threshold on ADI-R and ADOS-G, then eight of 20 cases of PLI and none of the 18 cases of SLI met the criterion.

In relation to ‘criterion standard’ consensus autism diagnosis, this criterion give sensitivity and specificity of more than 80% in a US sample.

For the broadest definition, where ASD is diagnosed if ASD criteria are reached on either instrument, 19 of 20 PLI cases and 6 of 18 SLI cases met the criterion.

However, previous research has shown a significant loss of specificity with this latter criterion, with many non autistic ‘false positives’ being included.

Reading- discussion

Many seen as language impaired in childhood met diagnostic criteria for ASD in adulthood. This was particularly true for those judged to have pragmatic impairments in childhood. The diagnostic criteria for autism came from the DSM-III or DSM-III-R, which adopted more stringent criteria, and milder forms of autism (ASDs) were not well recognized.

The broadening of diagnostic criteria for autism is apparent as 9-10-year-old children had a rate of 24.8 per 10 000 for cases, rising to 38.9 for diagnosis of autism, and to 116.1 per 10 000 for diagnosis of ASD.

Diagnostic substitution findings have been inconsistent. A UK study found a decline in frequency of language disorder that mirrored the increase in autism, but a US study of children enrolled in special education found no such pattern. However, the latter study included children with relatively mild speech or language difficulties, which may have masked a decline in diagnosis of rarer receptive language disorders.

Some authors argued that children developed autistic symptoms as they grew older. In our sample, this is most plausible for participants who did not show signs of autism according to parental report but did score in the ASD/ autism range on the ADOS G (3 SLI cases and 3 PLI cases). We found that parents often gave vivid and highly specific examples of behaviours that would lead to a clear coding of abnormality on ADI-R.

There are several reasons why an autism diagnosis might not have occurred. These children were not problematic for their parents. Their behaviour, although often odd, was not usually disruptive. This could have led to a reluctance of professionals to diagnose autism even when the signs were marked, because most provision for children with autism would have catered for children with much more severe difficulties. However, our impression was that, in most cases, autism was considered an inappropriate diagnosis because these children were communicative. Wing regarded such children as falling on the autistic spectrum, but they did not show the ‘aloof’ profile typical of autism.

A limitation of our study is the small sample size. Only 41% of contacted volunteered took part in our follow-up. Nevertheless, we were able to show that the responders were representative of the larger pool of potential participants in terms of language subtype, nonverbal ability, and receptive language level. At follow-up, we were able to assess ASD symptoms in the young people themselves and to obtain a retrospective report of symptoms in childhood from their parents, and thus demonstrate in individual participants how a given symptom profile related to changes in diagnostic practices over time.

Reading- conclusion

This study provides direct evidence of diagnostic substitution, indicating that many children diagnosed with severe language disorders in the 1980-90s displayed behaviours that merit a diagnosis of ASD.

This is a direct result of changing diagnostic criteria from DSM-III to DSM-IIIR and DSM-IV. We can’t conclude that an increasing prevalence of autism is only because of broadening diagnostic criteria, but secular changes in diagnostic concepts have led to diagnostic reassignment from language disorder to autistic disorder.

Our study also has implications for the research literature on developmental language disorders. Many studies of children with receptive language disorder need to be re-evaluated as they will have included children who would nowadays be regarded as having ASD