week 3; atypical development: diagnosis

Diagnosing William’s Syndrome

physical and cognitive features

more sunken nasal bridge, gaps in teeth, all prominent, but if not prominent when younger may test later on for cognitive profile

confirmed with a genetic test

blood test to identify absence of the ELN (elastin) gene, if absent the chances are they may have William’s Syndrome

the laboratory test used to detect the elastin gene is called fluorescent in situ hybridilization (FISH)

Down Syndrome: Prenatal

Screening test available between 10-14 weeks of pregnancy - Typically carried out at the 12 week scan

‘Combined’ test- has two primary parts

Blood test (Mother’s blood contains DNA from the foetus)

Nuchal translucency scan (checks the build of fluid at the back of the baby’s neck, the larger it is the greater the chance of a chromosomal abnormality)

If this test shows a ‘high risk’ then the mother would be offered an amniocentesis to confirm

Take a sample of the amniotic fluid

Voluntary

Down syndrome: post-natal

check physical characteristics

takes a while for features to take shape often, so may not be picked up on immediately

if unclear, follow up with a blood test

check for the presence of an extra chromosome

Conditions that are trickier to diagnose

ADHD

Autism

comorbidity

ADHD and autism frequently co-occur, with comorbidity rates potentially as high as 70% (Antshel & Russo, 2019),

ADHD is one of the most commonly comorbid conditions with autism

The previous edition of the DSM (DSM-4, 2000) prohibited dual diagnosis of autism and ADHD

Listed as two separate conditions in the DSM-5, hence why we discuss as two separate conditions throughout these lectures

Nevertheless, worth bearing in mind that many traits associated with ADHD overlap with traits associated with autism

Diagnosing ADHD

Initial referral often made in school (e.g. by SENCO).

Primary Care

GP / Social worker / Educational Psychologist

Secondary Care

Psychiatrist / Psychologist working within CAMHS (child and adolescent mental health service).

Diagnosis based on:

Discussion about behaviour in a range of different settings (e.g. school, home, etc)

Full developmental and psychiatric history and observer reports

Assessment of the person's mental state.

Screening instruments can be used to supplement diagnosis (but not on their own).

Conner’s rating scales

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

Diagnosing ASC

Initial referral often made by parents / school / GP.

Referral made to secondary care (e.g. CAMHS)

Autism assessment:

detailed questions about parent's or carer's concerns and, if appropriate, the child's or young person's concerns

details of the child's or young person's experiences of home life, education and social care a developmental history, focusing on developmental and behavioural features consistent with ICD-10 or DSM-5 criteria (consider using an autism-specific tool to gather this information)

a medical history, including prenatal, perinatal and family history, and past and current health conditions

a physical examination

Diagnostic manuals

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (currently 5th Edition, DSM-V, published in 2013)

International Classification of Diseases (currently 11th Edition, ICD-11)

DSM-5 Criteria for ADHD

Inattention: Six or more symptoms of inattention for children up to age 16 years, or five or more for adolescents age 17 years and older and adults; symptoms of inattention have been present for at least 6 months, and they are inappropriate for developmental level:

Often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, at work, or with other activities.

Often has trouble holding attention on tasks or play activities.

Often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly.

Often does not follow through on instructions and fails to finish schoolwork, chores, or duties in the workplace (e.g., loses focus, side-tracked).

Often has trouble organizing tasks and activities.

Often avoids, dislikes, or is reluctant to do tasks that require mental effort over a long period of time (such as schoolwork or homework).

Often loses things necessary for tasks and activities (e.g. school materials, pencils, books, tools, wallets, keys, paperwork, eyeglasses, mobile telephones).

Is often easily distracted

Is often forgetful in daily activities.

Hyperactivity and Impulsivity: Six or more symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity for children up to age 16 years, or five or more for adolescents age 17 years and older and adults; symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity have been present for at least 6 months to an extent that is disruptive and inappropriate for the person’s developmental level:

Often fidgets with or taps hands or feet, or squirms in seat.

Often leaves seat in situations when remaining seated is expected.

Often runs about or climbs in situations where it is not appropriate (adolescents or adults may be limited to feeling restless).

Often unable to play or take part in leisure activities quietly.

Is often “on the go” acting as if “driven by a motor”.

Often talks excessively.

Often blurts out an answer before a question has been completed.

Often has trouble waiting their turn.

Often interrupts or intrudes on others (e.g., butts into conversations or games)

DSM-5: Criteria for Autism

Persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts (You need to have all of these to be diagnosed):

Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, ranging, for example, from abnormal social approach and failure of normal back-and-forth conversation; to reduced sharing of interests, emotions, or affect; to failure to initiate or respond to social interactions.

Deficits in nonverbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction, ranging, for example, from poorly integrated verbal and nonverbal communication; to abnormalities in eye contact and body language or deficits in understanding and use of gestures; to a total lack of facial expressions and nonverbal communication.

Deficits in developing, maintaining, and understand relationships, ranging, for example, from difficulties adjusting behaviour to suit various social contexts; to difficulties in sharing imaginative play or in making friends; to absence of interest in peers.

Diagnostic Criteria for ASD

Restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities, as manifested by at least two of the following, currently or by history:

Stereotyped or repetitive motor movements, use of objects, or speech (e.g., simple motor stereotypes, lining up toys or flipping objects, echolalia, idiosyncratic phrases).

Insistence on sameness, inflexible adherence to routines, or ritualized patterns of verbal or nonverbal behaviour (e.g., extreme distress at small changes, difficulties with transitions, rigid thinking patterns, greeting rituals, need to take same route or eat same food every day).

Highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus (e.g., strong attachment to or preoccupation with unusual objects, excessively circumscribed or perseverative interests).

Hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input or unusual interest in sensory aspects of the environment (e.g. apparent indifference to pain/temperature, adverse response to specific sounds or textures, excessive smelling or touching of objects, visual fascination with lights or movement).

Diagnosis: standardised tests

Standardised tools used in the diagnosis of ADHD

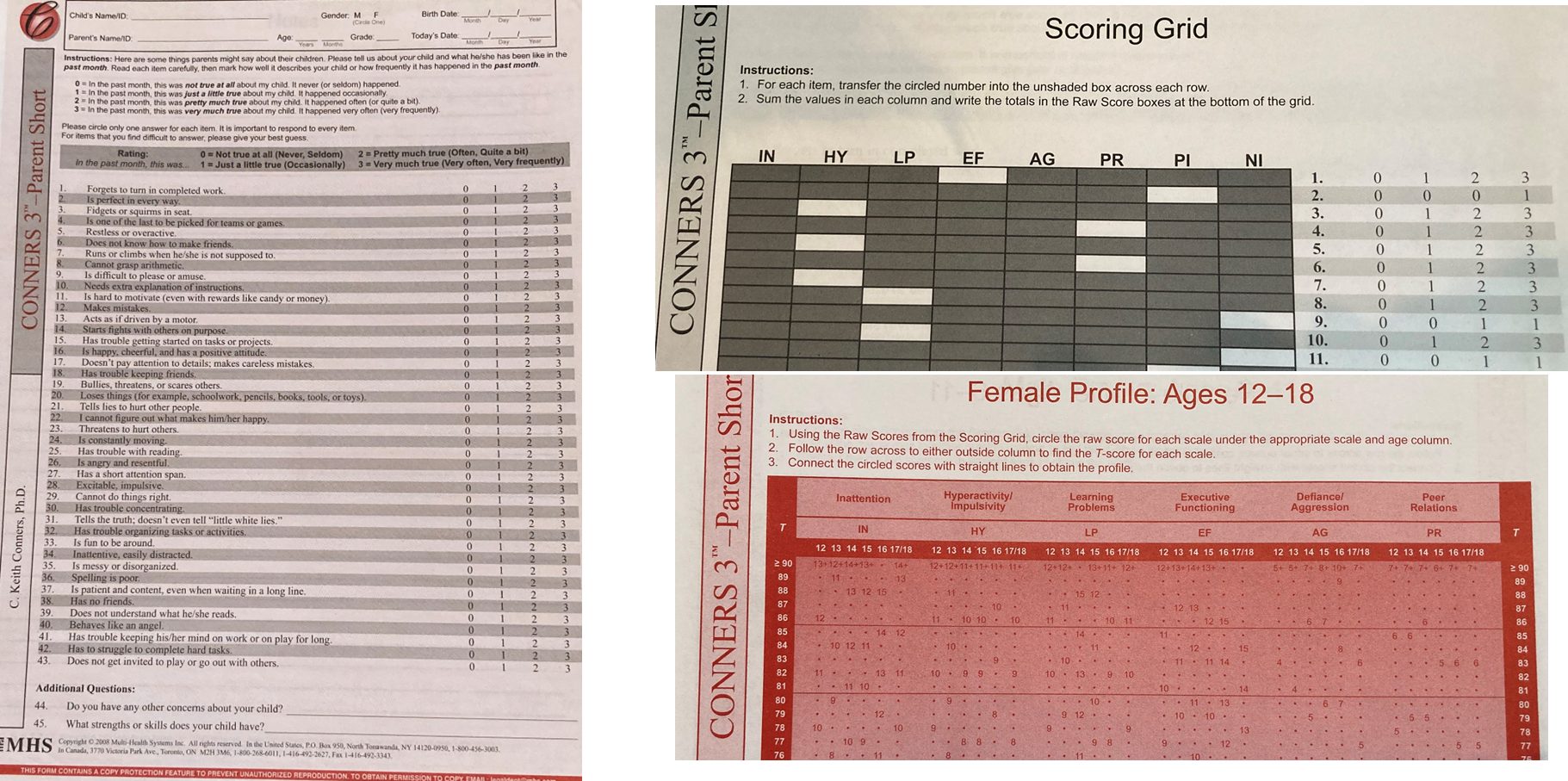

CONNERS SCALE FOR ASSESSING ADHD

Questionnaire screening for behaviours associated with ADHD, used as initial evaluation when ADHD is suspected

Three forms:

One for parents

One for teachers

Self-report to be completed by the child

Can be used during follow-up appointments to help doctors and parents monitor how well certain medications or behaviour-modification techniques are working.

The Conners Scale:

43 questions in total

The psychologist will total the scores from each area of the test. They will assign the raw scores to the correct age group column within each scale. The scores are then converted to standardized scores, known as T-scores.

Standardised tools used in the diagnosis of ASC

AUTISM DIAGNOSTIC OBSERVATIONAL SCHEDULE (ADOS)

Semi- Structured Interview. Code interaction for presence / absence of certain key behaviours, e.g. eye-contact, reciprocal interaction, turn-taking, imaginative play, non-verbal communication.

Five modules

Toddler: 12 – 30 months (no consistent speech)

Module 1: 31 months + (no consistent speech)

Module 2: Children any age (not verbally fluent)

Module 3: Children & young adolescents (verbally fluent)

Module 4: older adolescents & adults (verbally fluent)

•AUTISM DIAGNOSTIC INVENTORY (ADI)

Parent / caregiver interview focusing on developmental milestones and social behaviour.

Focus on age 4 / 5

•Both of these instruments require formal training before use.

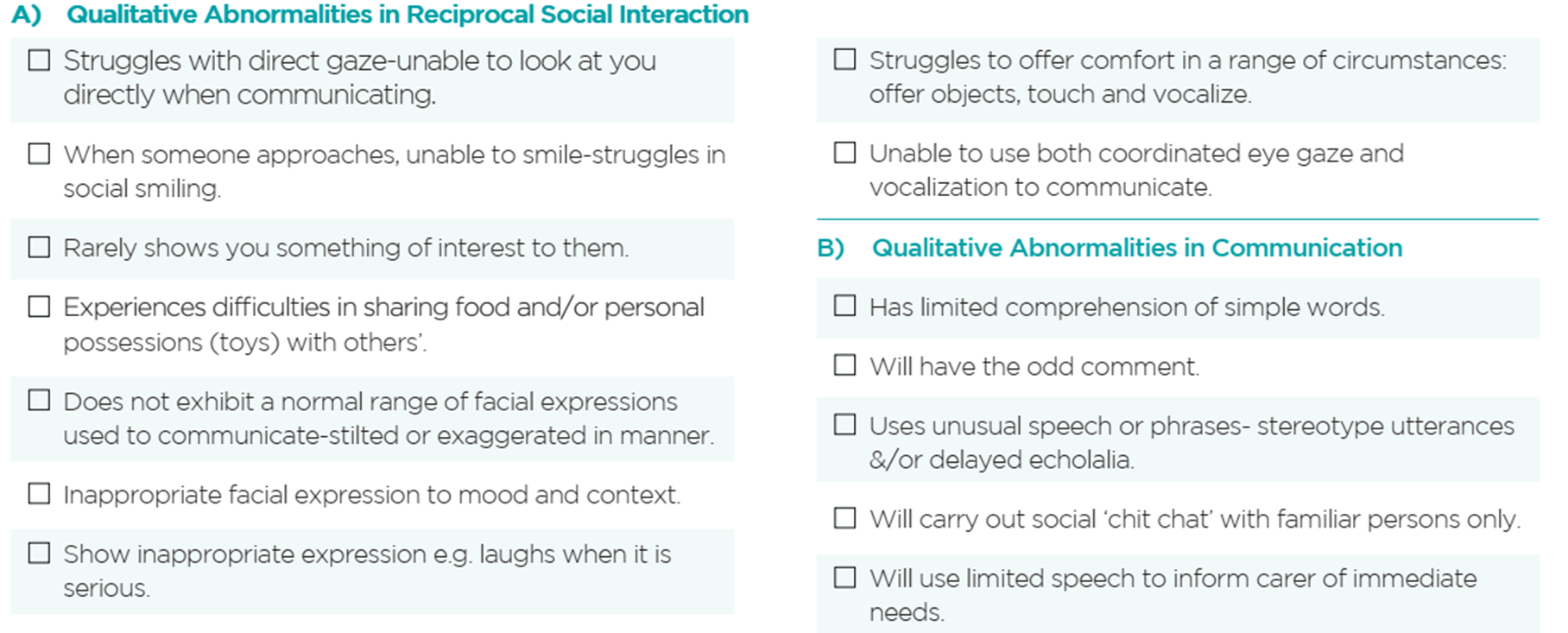

Example questions from the ADI

ADOS:

each behaviour has its own code

you add certain codes together to get an overall score for each domain of the DSM-5 Criteria

the pp’s scare on the two domains determines if they would be classed as autistic

How early can ASC be diagnosed

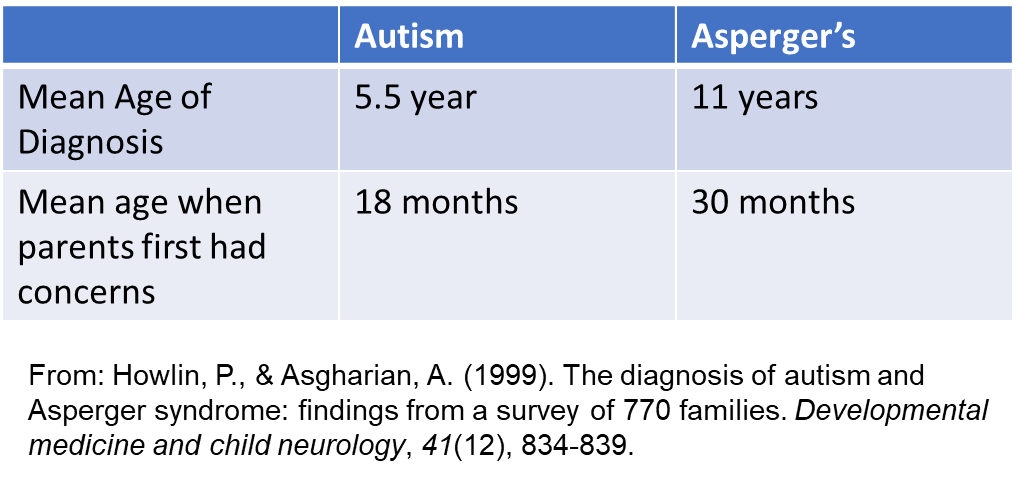

Based on a sample of 614 parents of children with autism and 158 children with Asperger’s syndrome, the average for diagnosis is shown in the table.

ASC is very rarely diagnosed before two years of age. Especially in the UK. Some countries carry out ASC screening, and the youngest age at which a child is diagnosed with ASC is ~ 2 years old.

There are a growing number of people being diagnosed with ASC in adulthood.

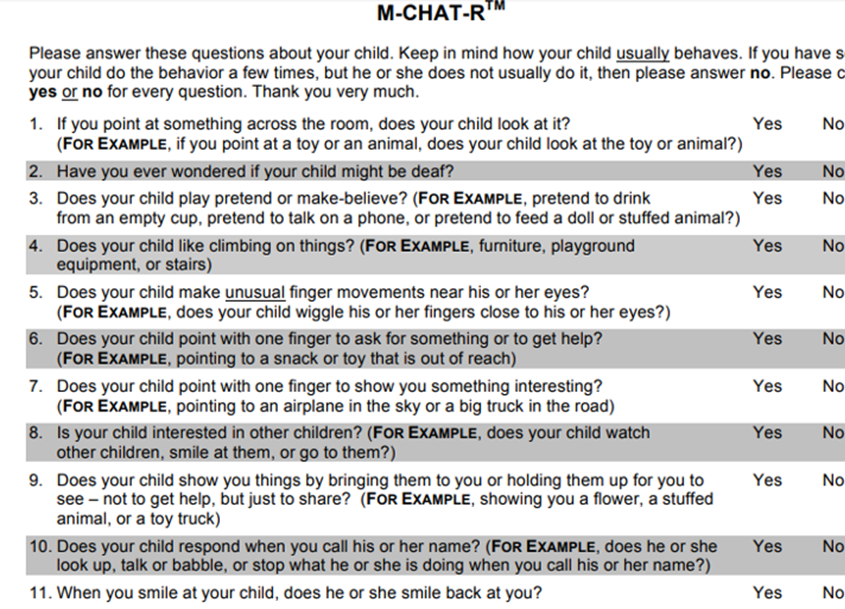

ASC Screening: the M-CHAT

A questionnaire used for screening toddlers for ASC is the M-CHAT (modified checklist for autism in toddlers).

This has been shown to be very useful in children aged between 16 and 36 months in terms of flagging up issues in development.

In one study, children who screened positive on the M-CHAT were 114 times more likely to receive an ASC diagnosis than children who screened negative.

However, while the M-CHAT is useful for screening for possible “red-flags” in development, it is not particularly sensitive for detecting ONLY autism, in this age group.

For example, it also picks up cases of children who may have developmental delay, but not necessarily ASC.

For this reason, researchers who are aiming to develop tools for early-identification of ASC, have started to study the “infant-siblings” of older children with a diagnosis of ASC.

“Infant siblings Approach”

ASC diagnosis typically made at around 4 years old (but can be a lot later).

Because of the genetic association with ASC, there is an increased chance (1 in 5) that a child with an older sibling who has a diagnosis of ASC will also go on to be diagnosed with ASC.

Therefore, looking for early markers for ASC in these children is considered a fruitful approach.

Techniques for early detection

The methodologies used in the infants'-sibs approach

Functional Near Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS)

Electroencephalogram (EEG)

Eye-tracking

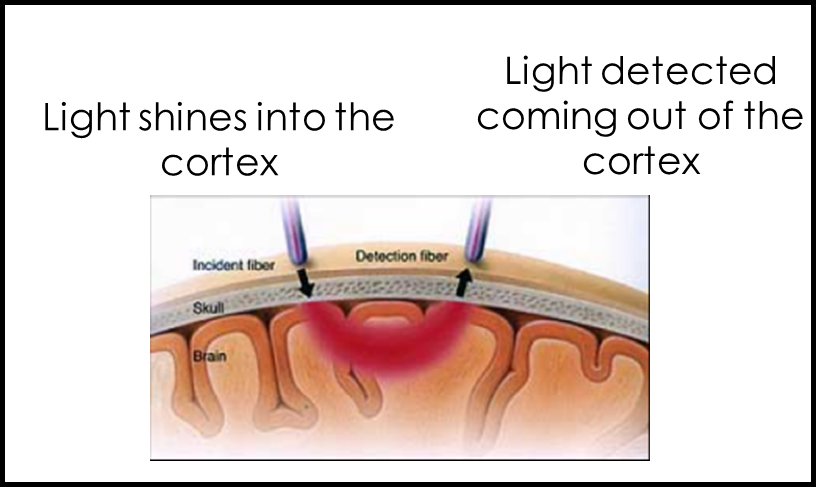

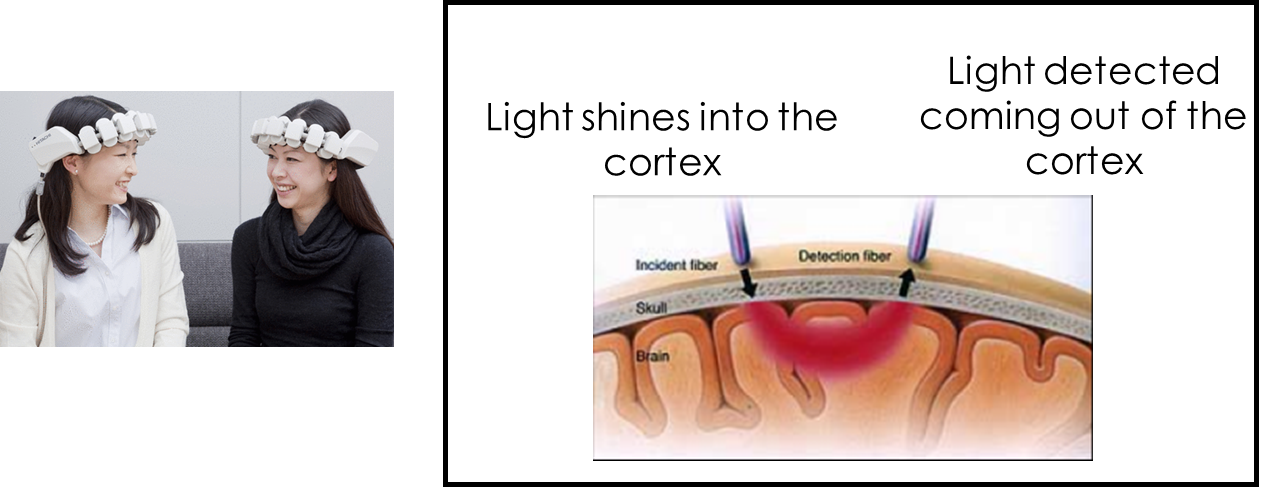

Functional Near Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS)

Optical Imaging Method (like a fit-bit measuring your heart-beat).

Shine light in, measure light coming out. Light that doesn’t exit the cortex has been absorbed.

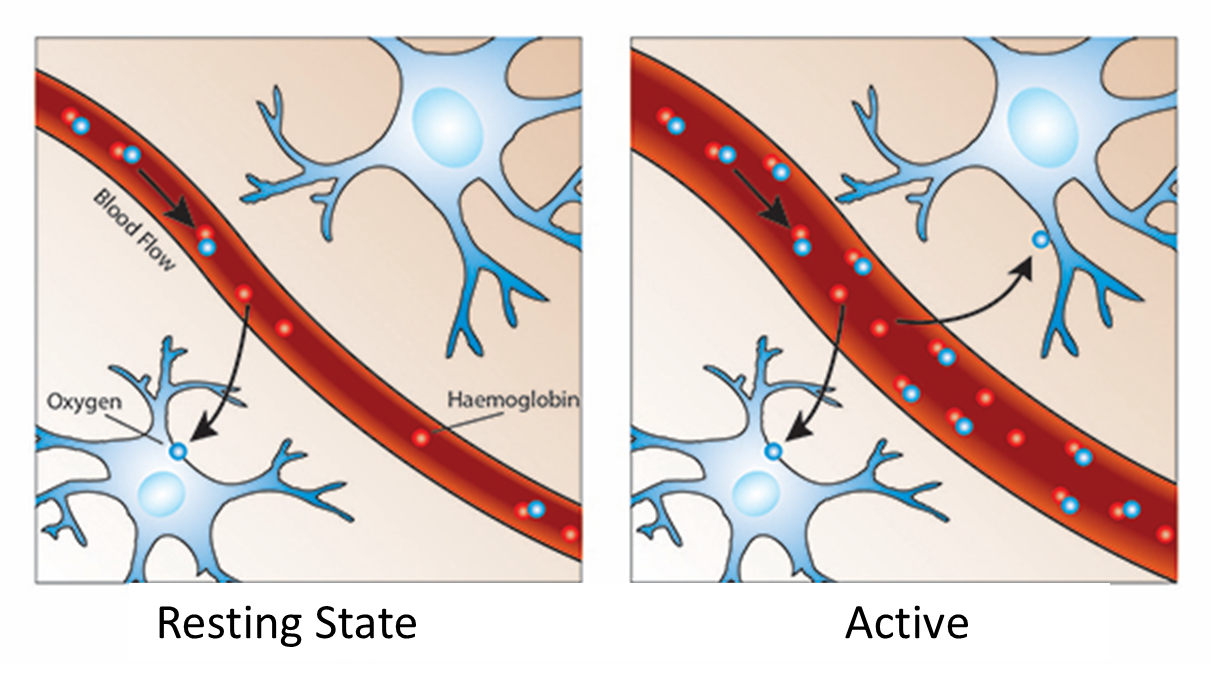

The main absorber of near-infrared light is haemoglobin. Therefore shining in near-infrared light allows us to measure haemoglobin.

Measuring absorption can tell us about blood flow.

Oxygen is delivered to neurons by haemoglobin in capillary red blood cells

more haemoglobin present in areas of the brain when it needs to replenish the oxygen used by active neurons

Using fNIRS to investigate early-markers of ASC

Recruited infants between 4-6 months of age:

Infant siblings of an older child with ASC (increased chance of having ASC)

Infant siblings of an older child without ASC (lower chance of having ASC)

Showed videos of social and non-social stimuli.

The infants with a higher chance of having ASC were found to show reduced activity over temporal cortex in response to social stimuli compared to infants with reduced chance of ASC.

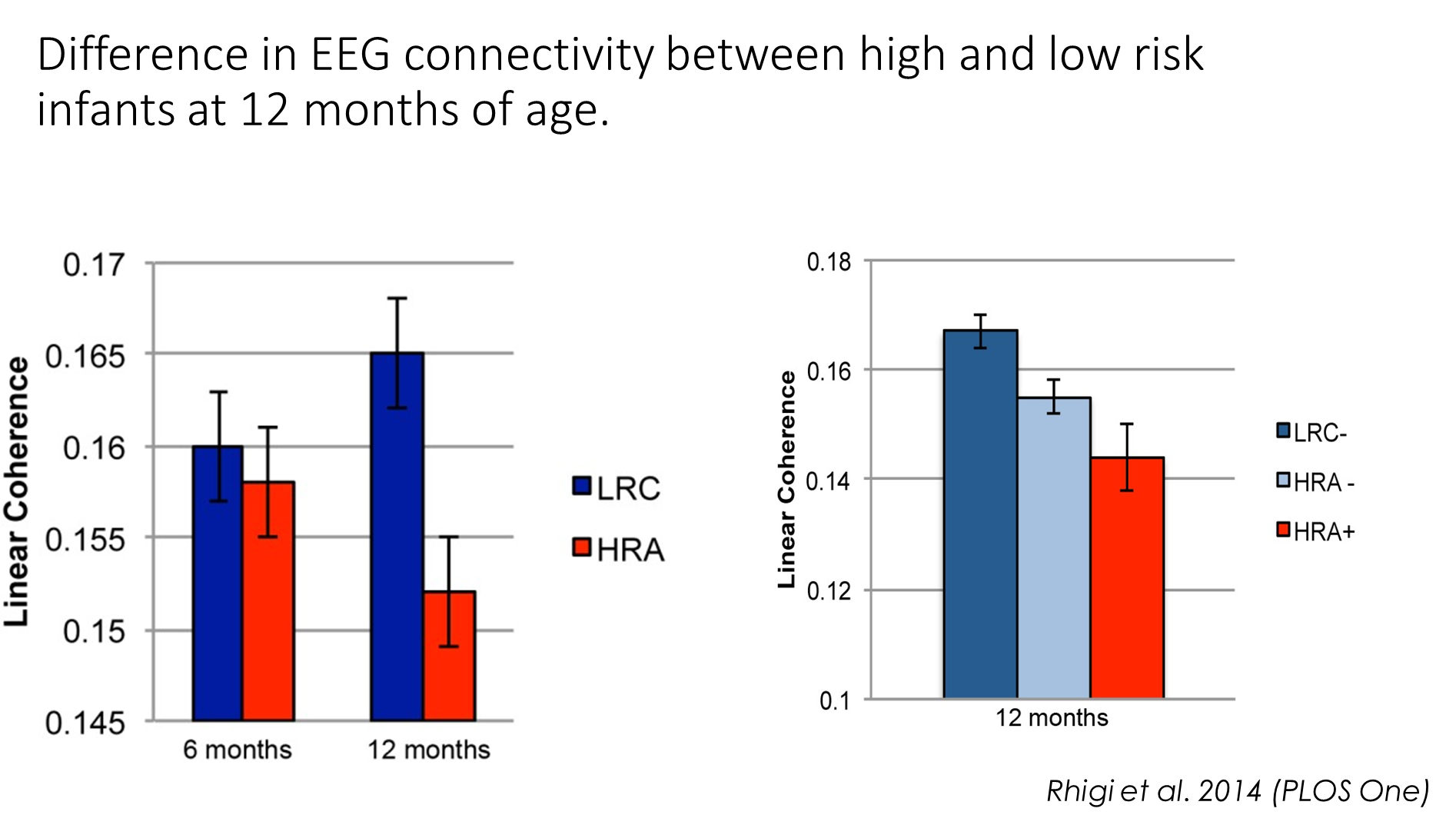

electroencephalography (EEG)

EEG measures electrical signals generated by the brain through electrodes placed at the scalp

EEG signals are produced by cortical field activity and are measured as changes in voltage, recorded at the scalp, over time.

Analysis of EEG signals may be task dependent or task independent

EEG data can be analysed in many different ways- connectivity between different brain regions (coherence)

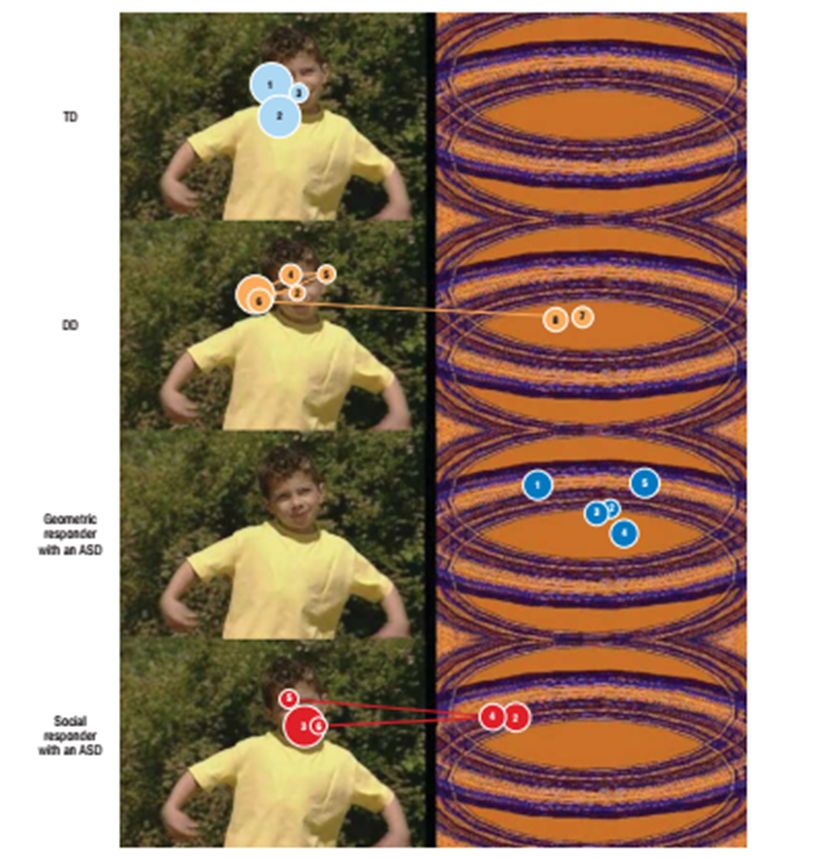

Eye tracking:

Difference in looking behaviour (measured with eye-trackers) in toddlers with a diagnosis of ASC (identified during an earlier screening study).

Majority of neurotypical toddlers spent more time looking at the social videos than the geometric patterns.

Some of the toddlers with ASC spent more time looking at the geometric videos.

“If a toddler spent more than 69% of his or her time fixating on geometric patterns, then the positive predictive value for accurately classifying that toddler as having an ASD was 100%.”

Challenges of the infant-sibs/ early detection approach

While differences can be seen at a group-level, the work has not yet yielded clear biomarkers that are useful at an individual level.

Most of the studies do not follow up the ‘at-risk’ infants in order to confirm whether or not they do receive a later ASC diagnosis.

Therefore, group differences between high and low risk infants could be reflecting the “broader autism phenotype” rather than specific biomarkers for autism.

ASC is a very heterogeneous condition, and there is a lot of individual variability in the way that ASC is expressed. Therefore, aiming to identify a single neural or behavioural construct that can classify ASC is a difficult (impossible?) challenge.

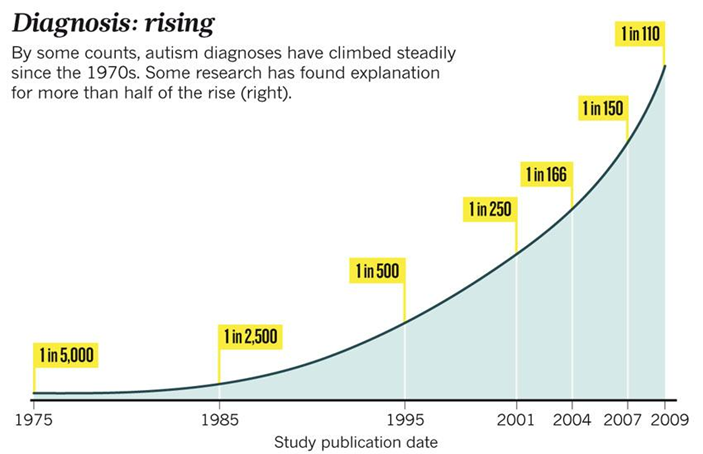

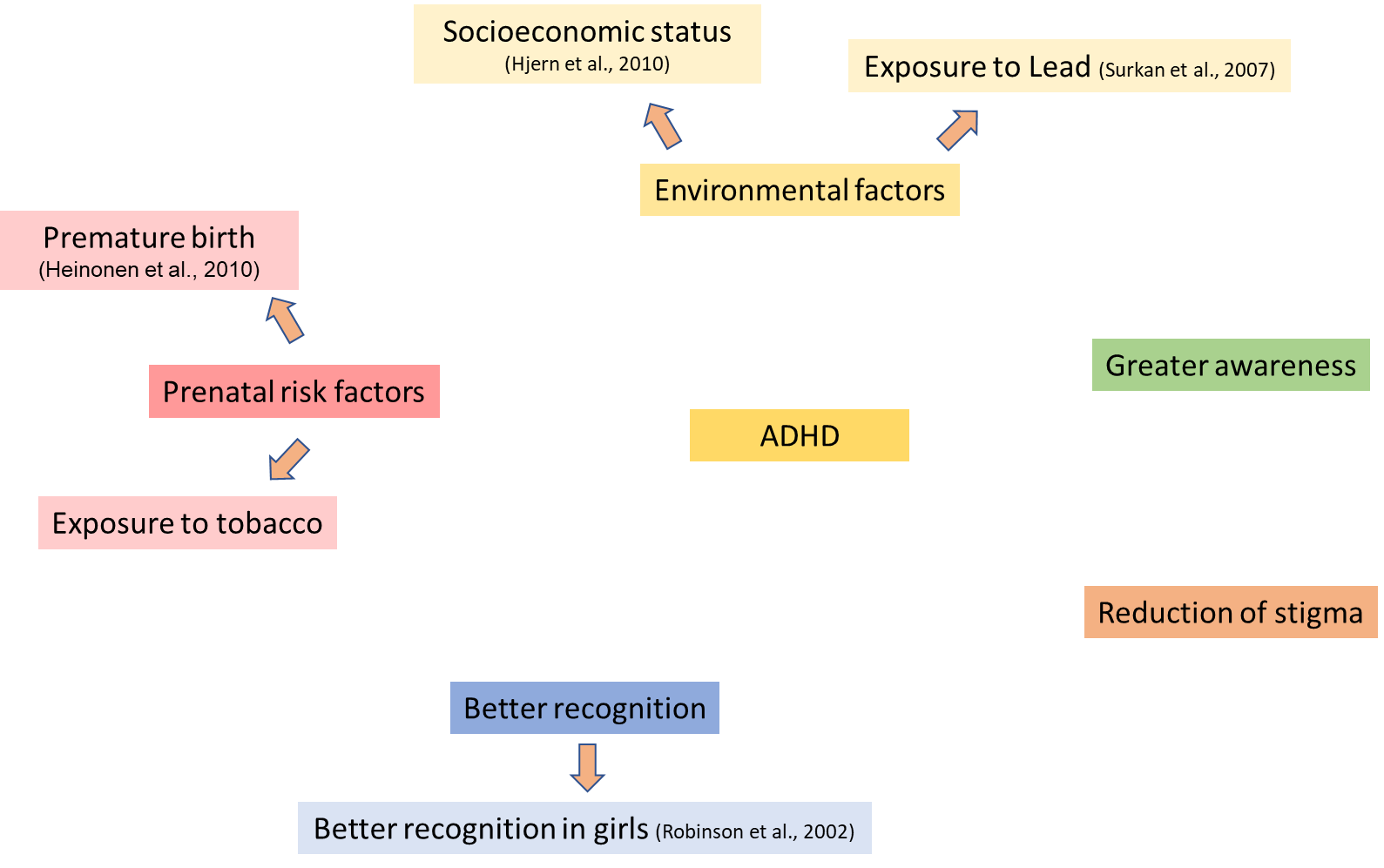

Prevalence of ADHD & ASC

Both ADHD and ASC diagnoses have increased over time

Bugha et al., 2011 –7,461 households completed an autism screening questionnaire

5,102 people eligible for phase two (AQ20 score >5)

Phase 2 = Face to face diagnostic evaluation

Number of people meeting diagnostic criteria for autism = 9.8 per 1,000 (~1 in 100)

Prevalence of diagnosed ASC

According to the Centre for Disease Control (US), ASC prevalence rates in 8 year old children are:

2008 = 1 in 88

2010 = 1 in 68

2012 = 1 in 69

2014 = 1 in 58

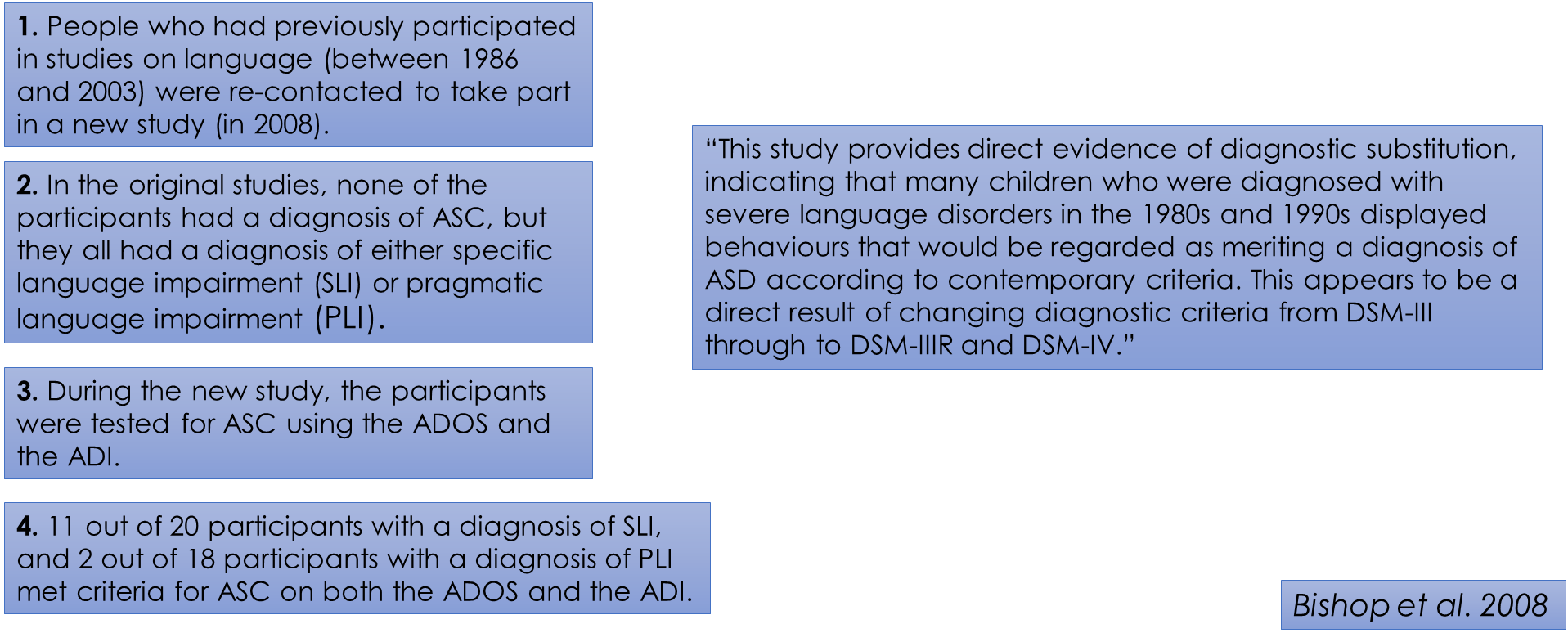

“diagnostic substitution”

Children who would now meet the diagnostic criteria for ASC, were previously diagnosed with other conditions, e.g. language disorders.

Reading

Autism and diagnostic substitution: evidence from a study of adults with a history of developmental language disorder

Rates of diagnosis of autism have risen since 1980, raising the question of whether some children who previously had other diagnoses are now being diagnosed with autism. We applied contemporary diagnostic criteria for autism to adults with a history of developmental language disorder, to discover whether diagnostic substitution has taken place. A total of 38 adults (aged 15–31y; 31 males, seven females) who had participated in studies of developmental language disorder during childhood were given the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule – Generic. Their parents completed the Autism Diagnostic Interview – Revised, which relies largely on symptoms present at age 4 to 5 years to diagnose autism. Eight individuals met criteria for autism on both instruments, and a further four met criteria for milder forms of autistic spectrum disorder. Most individuals with autism had been identified with pragmatic impairments in childhood. Some children who would nowadays be diagnosed unambiguously with autistic disorder had been diagnosed with developmental language disorder in the past. This finding has implications for our understanding of the epidemiology of autism.

Rates of diagnosis of autism have risen markedly over the past three decades.1 According to the ‘autism epidemic’ hypothesis, the rise is genuine, whereas the ‘diagnostic sub stitution’ hypothesis maintains that the true prevalence of the syndrome is constant but the diagnostic boundaries have broadened, so that more children who would previously have had some other diagnosis are now identified with autism. Specific developmental language disorder is a cate gory where diagnostic substitution seems plausible, given that: (1) communication problems are a core feature of autism; (2) there has been debate over diagnostic bound aries between autism and language disorder; and (3) autism is increasingly being recognized in children with normal IQ.2 We used follow-up data to test the hypothesis that some chil dren diagnosed with developmental language disorder 5 to 25 years ago would currently be diagnosed with autism.

Method

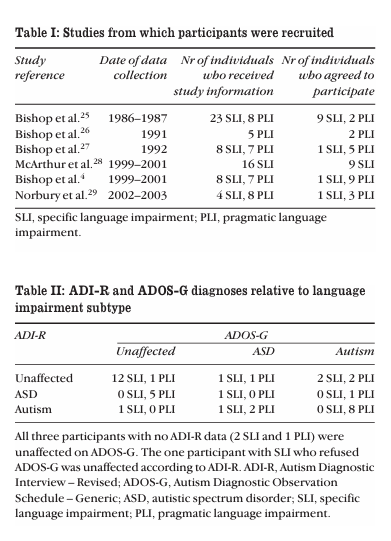

participants

Participants were drawn from a pool of children who had taken part in a series of studies of developmental language disorder conducted in the period 1986 to 2003 (see Table I). All children had been in receipt of services for children with language impairments, in most cases attending special schools. School records had been checked at the time of the original study for diagnostic information. No child had a pre vious diagnosis of autistic disorder; indeed, autism was an exclusionary criterion for admission to the special schools that were involved in the study. Also excluded from the pre sent study were children who had a known cause for their language impairment, such as brain injury, a known syn drome, or physical abnormality of the articulators. The quan tity and quality of data available from childhood varied from study to study, but in all cases there was at least one expres sive and one receptive language measure, and all partici pants had a nonverbal IQ of at least 80. We expected that the subtype of language disorder might be important, given the long-standing debate about the rela tionship between autistic disorder and pragmatic language impairment (PLI), formerly known as ‘semantic–pragmatic disorder’.3–7 Insofar as there is diagnostic substitution, one would predict that this would be most marked for those with the characteristics of PLI, because pragmatic oddities in com munication are one of the diagnostic features of autism. The studies shown in Table I took place at a time when the con cept of ‘semantic–pragmatic disorder’ was evolving, and PLI had been identified by a variety of methods. In the early stud ies, a simple teacher checklist had been used, listing the symptoms identified by Bishop and Rosenbloom8 and Rapin and Allen.9 This checklist went through various transforma tions and ultimately led to the development of the Children’s Communication Checklist,10 on which a specific cut-off for PLI was given. For some of the studies in Table I, recruitment had specifically focused on individuals with PLI, so the pro portions with this language profile are higher than would be expected in this population in general; Conti-Ramdsen et al.11 found that about 10% of children enrolled in special lan guage classes in the UK had this profile. For participants in studies performed before 1999, tracing was conducted through the Office of National Statistics; for the later studies, direct contact was made with the use of addresses held on file, but only a subset of participants from the final two studies were contacted to avoid over-testing and to exclude those who had not yet reached adulthood. Table I shows the number who agreed to receive information about the study and the number who agreed to participate. Those who agreed to take part did not differ from the remainder of the sample (including those we could not con tact) in terms of either nonverbal ability or receptive lan guage level in childhood. They represented 26% of cases of specific language impairment (SLI) and 24% of PLI among the original study participants.

Autism Diagnostic Assessments in Adulthood

As part of their diagnostic workup at follow-up in adulthood, participants were given the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule – Generic (ADOS-G)12by a trained examiner (AW or EL) and their parents were given the Autism Diagnostic Interview – Revised (ADI-R)13by a trained interviewer (AW, HW, or DB). Together, these two instruments provide the ‘cri terion standard’ for autism diagnosis, with the ADOS-G pro viding contemporaneous information about diagnostic symptomatology, and the ADI-R providing information about early development, with a particular focus on the child’s behaviour at age 4 to 5 years. Both instruments provide cut offs for autism diagnosis, and the ADOS-G also provides cut offs for pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified; that is, the milder variant of autism, more com monly referred to as autistic spectrum disorder (ASD). On the ADI-R we coded participants who fell above threshold for autism on two of the three domains (communication, social ization, and repetitive behaviour) as meeting criteria for ASD. Informed consent was obtained from participants as well as parents. This research was approved by the Central University Research Ethics Committee of Oxford University. One adult participant did not complete ADOS-G (as a result of psychiatric illness) and three parents did not com plete the ADI-R (one set of parents could not be contacted, and two refused to participate). All of these participants were male. For the remaining 38 participants, both sources of information were available. The 31 males and seven females were between 15 and 31 years of age at follow-up.

Results

Table II shows the number of participants who fell above cut offs for autistic disorder in relation to their original subtype of language impairment. The association between language subgroup and diagnosis from parental report on ADI-R was statistically significant (χ2=16.09, degrees of freedom [df]=2, p<0.001). The association between language sub group and diagnosis was again statistically significant when ADOS-G was the basis for diagnosis (χ2=9.21, df=2, p=0.01). If a strict definition of autism was used, requiring scores above threshold for autism on both ADI-R and ADOS-G, then eight of 20 cases of PLI and none of the 18 cases of SLI met the criterion. In relation to ‘criterion standard’ consensus autism diagnosis, this criterion has been shown to give sensi tivity and specificity of more than 80% in a US sample.14A broader definition, requiring a diagnosis of ASD or autism on both measures, selected 11 of 20 cases of PLI and two cases of SLI. For the broadest possible definition, where ASD is diag nosed if ASD criteria are reached on either instrument, then 19 of 20 PLI cases and 6 of 18 SLI cases met the criterion. However, previous research has shown a significant loss of specificity when this latter criterion is used, with many non autistic ‘false positives’ being included.14

Discussion

A high proportion of people who were regarded as language impaired rather than autistic when seen in childhood were deemed to meet contemporary diagnostic criteria for ASD in adulthood, on the basis of parental report of childhood symptoms and/or on the basis of current behaviour. This was particularly true for those who were judged to have pragmat ic impairments in childhood. Most of these individuals were first seen as children when the diagnostic criteria for autism came from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition (DSM-III) or the revised 3rd edition (DSM-III-R).15Both of these schemes, especially DSM-III, adopted more stringent criteria than are currently used, and milder forms of autism, currently referred to as ASDs, were not well recognized. The broadening of diagnostic criteria for autism is apparent in a recent epidemiological study of 9- to 10-year-old children which found a rate of 24.8 per 10 000 for cases where consensus diagnosis of autism was con firmed by both ADI-R and ADOS-G, rising to 38.9 for all cases of consensus diagnosis of autism, and to 116.1 per 10 000 for consensus diagnosis of ASD.16 Diagnostic substitution has previously been studied by comparing long-term trends in prevalence of autism versus developmental language disorders in epidemiological data, but findings have been inconsistent. A UK study using the General Practice Research Database found a decline in fre quency of language disorder that mirrored the increase in autism,17 but a US study of children enrolled in special edu cation found no such pattern.18 However, it is likely that the latter study included many children with relatively mild speech or language difficulties, and this may have masked a decline in diagnosis of rarer receptive language disorders. The only other follow-up study of which we are aware that used algorithms from autism diagnostic instruments with children diagnosed with developmental language disorder was performed by Conti-Ramsden et al.19 They studied a group of children originally recruited from language units (special classes) at 7 years of age. These children were given the ADOS-G and their parents were given the ADI-R when the children were 14 years old. The proportion of participants who met diagnostic criteria for autism on both ADI-R and ADOS-G was relatively low (3/76), but in total 11 children met criteria for autism on ADI-R, and 19 met criteria for ASD or autism on ADOS-G. These are lower rates than found in our study, but this could be explained by the fact that most of the sample were recruited in the early to mid 1990s, after the publication of DSM-III-R, which used broader diagnostic cri teria than DSM-III. In addition, our sample was selected to include a high proportion of individuals with PLI. Conti Ramsden et al. noted that there was no difference on lan guage tests between children who did and did not meet criteria for an ASD. However, they did not present any data on children’s pragmatic abilities. These authors argued against the idea of diagnostic sub stitution, instead proposing that some children had devel oped autistic symptoms as they grew older. They noted that ‘this sample were all definite cases of SLI as late as 7 years of age, when the stereotypical behaviours and atypical social skills characteristic of autism would have been visible if they had been present’ (p 626). In a similar vein, another study found autistic-like symptomatology in adulthood in a sample of individuals originally recruited because of developmental receptive language disorder in childhood, but the authors argued that this had developed with age, rather than being part of the original presentation.20,21 In our sample, this explanation is most plausible for those participants who did not show signs of autism according to parental report on the ADI-R but did score in the ASD or autism range on the ADOS G (three SLI cases and three PLI cases in Table II). However, for most individuals with autistic symptomatol ogy in the current study, and for just over half of those in the study by Conti-Ramsden et al., autistic symptoms were evi dent on parental report on the ADI-R, which uses an algo rithm based on behaviour observed at 4 to 5 years of age. Clearly, one must be cautious about interpreting retrospec tive reports of early childhood behaviours that are made some 20 or so years after the event. Furthermore, reports could be contaminated by parents’ having read about autism and thereby developing biased memories of their child’s early development. Nevertheless, we found that parents often gave vivid and highly specific examples of behaviours that would lead to a clear coding of abnormality on ADI-R, despite the fact that nobody had discussed a possible autism diagnosis with them. Some illustrative vignettes are given in Appendix I. This provides clear evidence of autistic sympto matology at the time when the children had been diagnosed with language disorder. It may seem remarkable that a diagnosis of autism was not made during childhood for the individuals featured in Appendix I, especially bearing in mind that these were chil dren who had typically undergone thorough assessments to access special educational services. There are several reasons why this might have occurred. One point to note is that these children were not, in general, particularly problematic for their parents. Their behaviour, although often odd, was not usually disruptive to family life. This could have led to a reluctance of professionals to diagnose autism even when the signs were marked, because most provision for children with autism would have catered for children with much more severe difficulties – see, for example, participant PLI07 (Appendix I), who was seen by an expert paediatric neurolo gist but not given a diagnosis. However, our impression was that, in most cases, autism was considered an inappropriate diagnosis because these children were communicative; as noted by Gernsbacher et al.,22to qualify for a DSM-III diagno sis of autism, a child had to exhibit a ‘pervasive lack of responsiveness to other people’. In its account of differential diagnosis from receptive language disorder, DSM-III stated ‘In Infantile Autism … no efforts are made to communicate or watch faces, whereas in Developmental Language Disorder, Receptive Type, the children will make eye contact and will often try to communicate through gestures’ (p 97). Such guidelines led clinicians to operate with a view of the autistic child as locked away in their own world, showing lit tle interest in people, and doing little other than engaging in stereotyped activities. Despite their social and communicative oddities, the par ticipants with PLI and autistic features in our current study did not usually resemble this picture in childhood; they tended instead to show profiles described by Wing23as either ‘passive’ (see participant PLI10) or ‘active but odd’ (see par ticipant PLI06). Wing regarded such children as falling on the autistic spectrum, but they did not show the ‘aloof’ profile typical of classic Kanner autism. Children who are ‘active but odd’, for instance, ‘make active social approaches that are naïve, odd, inappropriate and one-sided… These children might show quite complicated play, but observation shows that it is only concerned with one or a few themes and usual ly not shared with other children’ (p 1762). Those following DSM-III or DSM-III-R guidelines would not regard such chil dren as meeting criteria for autism. However, by DSM-IV-TR24 the differential diagnosis is based on ‘the characteristics of the communication impairment (e.g. stereotyped use of lan guage) and by the presence of a qualitative impairment in social interaction and restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped patterns of behavior’ (pp 60–61). A further point to note is that it is only with the development of objective diagnostic assessment in the form of ADI-R that the importance of bas ing diagnosis on behaviour at a given age (4–5y) has been emphasized. This is the age at which symptoms of autism are typically most pronounced. In some of our participants who met ADI-R criteria for autism, florid autistic symptomatology at 4 to 5 years of age had become much less apparent by mid dle childhood. A limitation of our study is the small sample size. Although we succeeded in tracing a relatively high proportion of indi viduals who had participated in early studies, only 41% of those contacted volunteered to take part in our follow-up. This is perhaps not surprising when one considers that we were focusing on individuals who had serious communica tion problems, often associated with poor literacy skills. Nevertheless, we were able to show that the responders were representative of the larger pool of potential participants in terms of language subtype, nonverbal ability, and receptive language level. The value of this sample is that, although small in size, it is unique in being well documented in terms of language characteristics in early childhood, and including many individuals first seen before the advent of DSM-IV. At follow-up, we were able to assess ASD symptoms in the young people themselves and to obtain a retrospective report of symptoms in childhood from their parents, and thus demonstrate in individual participants how a given symptom profile related to changes in diagnostic practices over time. Even though rates of autistic behaviours were high in our sample, especially in those with PLI, our study agrees with others4,19 in emphasizing the lack of a clear dividing line between language disorder and autism.

Conclusion

This study provides direct evidence of diagnostic substitu tion, indicating that many children who were diagnosed with severe language disorders in the 1980s and 1990s displayed behaviours that would be regarded as meriting a diagnosis of ASD according to contemporary criteria. This appears to be a direct result of changing diagnostic criteria from DSM-III through to DSM-IIIR and DSM-IV. As noted by Rutter,2 it would be rash to conclude that an increasing prevalence of autism is entirely explicable in terms of broadening diagnos tic criteria, but the data reported here illustrate how secular changes in diagnostic concepts and clinical awareness have led to diagnostic reassignment from language disorder to autistic disorder. It is likely that similar factors have operated to lead to a diagnosis of autism in other children who would hitherto have been regarded as cases of learning disability* or attention-deficit–hyperactivity disorder. Our study also has implications for our evaluation of the research literature on developmental language disorders. Many studies of chil dren with receptive language disorder that were published in the last century need to be re-evaluated on the grounds that they will have included children who would nowadays be regarded as having ASD