APUSH Period 7

1/255

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

256 Terms

Idealism in Foreign Policy

An approach to formulating foreign policy based on the premise that the United States must give major consideration to promoting human rights, self-determination, and democracy throughout the world. In this sense, U.S. foreign policy must be sensitive to morality and not driven by strict economic, strategic, international political, or domestic political self-interest.

The reason why U.S. foreign policy must give primary consideration to morality is because, as stated in the Declaration of Independence, all people are endowed with certain irrevocable rights—to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. The purpose of governments is to promote these ends. Democratic governments, which by definition are based on the consent of the governed, are the kind most likely to achieve this purpose.

In practical terms, this means that the U.S. should apply economic sanctions and, if necessary, military force to create changes in those governments that grossly violate the human rights of their people. In doing so, the United States should ideally work in conjunction with an international organization, such as the League of Nations or the United Nations, that is based on a commitment to enforcing human rights and international peace based on the observance of international law. However, if that organization is unwilling or unable to execute its responsibilities, the U.S. must do so on its own.

Realism in Foreign Policy

An approach to formulating foreign policy based on the premise that nations, like individuals, act in their own self-interest. With respect to international relations, this means that all nations act on the basis of their own economic, strategic, international political, and domestic political self-interest. Therefore, it is the responsibility of U.S. foreign policy to achieve these goals for the U.S. while at the same time recognizing that other major world powers will try to do the same.

Major world powers are those nations with the most developed economies and the most powerful militaries. Since these nations are industrialized, they necessarily need international markets not only to supply the natural resources essential for their industrial production but also to purchase the manufactured goods they export. For the sake of their economies, major world powers will therefore have certain geographical areas of the world that they regard as essential to their economic health. Furthermore, all major world powers will want to be able to protect themselves from foreign aggression, and they will exercise dominance of nearby geographical areas they regard as vital to their national security. For these economic and strategic reasons, all major world powers will have spheres of influence. With respect to relations among themselves, major world powers will inevitably have closer relations with those nations with whom they share economic and strategic interests. These relationships will become either de jure or de facto alliances based on mutually shared interests, and offsetting alliances will create a balance of power.

The goal of all major world powers should be to maintain the balance of power and avoid wars between opposed alliances since such a war would necessarily involve global conflict, creating the potential for catastrophic international chaos and carnage.

DIMES

Domestic Political:

refers to the effect politically within the country. Will the American people approve of and support this decision? Will the decision enhance or detract from the popularity of the government or a particular politician or party? Will the decision strengthen or weaken our political system?

International Political:

refers to the effect on other countries. Will other nations see our country more positively or negatively as a result of the decision? Are there countries that would be compelled to take some action or adopt some behavior as a result of the decision? Would the decision create new friends or new enemies?

Moral:

refers to the rightness or wrongness of the decision in terms of character and principles. We can evaluate policies based on the moral vision of the people of the time and based on the moral vision of other people including ourselves. Does the decision enhance or harm our values such as a belief in democracy, equality, religious freedom, truth, honesty, compassion, responsibility and fairness?

Economic:

refers to the effect the decision will have on our prosperity. Will this produce more or less wealth or resources? Will some classes of people benefit more than others? What will the effect be on our way of life?

Strategic:

refers to gaining overall or long-term advantage militarily, economically, or politically. Will the decision strengthen or weaken our position in the world? Will the decision increase our overall security or our ability to acquire resources and conduct trade?

The Age of Imperialism

A periodization concept, used by historians, describing the last quarter of the nineteenth century in world history, when European empires carved up large portions of the world among themselves. Their justification was to bring "civilization," by which they meant Western values, labor practices, and Christianity. The process generally resulted in the economic exploitation of the colonized people and areas. During this period, U.S. foreign policy was influenced by, and in some ways came to resemble, that of other European empires.

Alfred T. Mahan's The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1890

A naval officer and his book that argued that no nation could prosper without a large fleet of ships engaged in international trade, protected by a powerful navy operating from overseas bases. The argument offered strategic considerations that were used to justify U.S. imperialistic expansion during the era.

"Yellow Press"

Mass-circulation newspapers (so called by their critics after the color in which a popular comic strip was printed) that mixed sensational accounts of crime and political corruption with aggressive appeals to nationalistic, patriotic sentiments. They contributed the public's support of imperialistic expansion in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Annexation of Hawaii, 1898

Although independent, Hawaii already had close economic ties with the U.S. in the late 19th century, and its economy was dominated by American-owned sugar plantations that employed native islanders and Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino laborers. In 1893, a group of American planters organized a rebellion that overthrew the Hawaii government of Queen Liliuokalani, and in 1898, the U.S. annexed the Hawaiian island, reflecting its growing empire during the Age of Imperialism.

Explosion of The U.S.S. Maine, 1898

One of the causes of U.S. entrance into the Spanish-American War. This was a U.S. battleship that exploded in Havana Harbor in 1898, resulting in 266 deaths; the American public, assuming that the Spanish had mined the ship, clamored for war (popular slogan: "Remember the Maine, and to hell with Spain!"), making this event a major domestic political consideration ("DIMES") that pushed the U.S. to declare war on Spain two months later.

Spanish-American War, 1898

A conflict fought between Spain and the United States in 1898. Hostilities began in the aftermath of the internal explosion of the U.S.S. Maine in Cuba leading to United States intervention in the Cuban War of Independence. Teddy Roosevelt made a name for himself with his "Rough Riders" in the battle of San Juan Hill. As a result of America's victory over Spain, America gained influence over Cuba, acquired Puerto Rico and Spain's Pacific possessions (Guam and the Philippines), and got involved in the bloody Philippine-American War. The war illustrates how the U.S. became an empire during the Age of Imperialism.

Teller Amendment (1898)

Congress adopted and then added this amendment to the Declaration of War on Spain in 1898. It promised that the U.S. had no intention of annexing or dominating Cuba after winning the Spanish-American War. It was intended to underscore America's humanitarian motives (Idealism) for intervening on the side of Cuba. However, this Amedment was later contradicted by the Platt Amendment (realism).

The Platt Amendment, 1901

Despite having passed the Teller Amendment at the beginning of the Spanish American War (which said the U.S. had no intention of annexing or dominating the island of Cuba), in 1901, President McKinley forced Cuba's new government to insert this amendment in the Cuban constitution, which authorized the U.S. to intervene militarily in Cuba whenever it saw fit and gave the U.S. permanent naval stations in Cuba, including what is now Guantanamo Bay (realism). This amendment illustrates how the U.S. was becoming an empire during the Age of Imperialism. The U.S. would exercise significant influence over Cuba until Fidel Castro's communist revolution in 1959.

The Open Door Policy (with China)

In this 1899 policy, shortly after the Spanish American War, the U.S. demanded that European powers that had recently divided China into commercial spheres of influence grant equal access to American exports to Chinese markets. Thus American territorial possessions in the Pacific (Guam, Philippines, Hawaii) during the Age of Imperialism had more to do with trade with China than with large-scale American settlement on those islands.

The White Man's Burden

This idea, popularized by an 1899 poem by Rudyard Kipling, suggested that "white" imperialism contributed to the "progress" of "civilization" by "uplifting" what Europeans and Americans perceived as "backward," "inferior," "savage" people in the non-industrialized world and helping them adopt the values of modernity. In this poem, Kipling urged the U.S. to take up the "burden" of empire, as had Britain and other European nations. The poem coincided with the beginning of the Philippine-American War and U.S. Senate ratification of the treaty that placed Puerto Rico, Guam, Cuba, and the Philippines under American control. This racialized notion became a euphemism for imperialism, and it gave imperialism an idealistic (but deeply racist) justification.

The Philippine War, 1899-1903

A conflict between the U.S., which was trying to establish control of the former Spanish colony, the Philippines, and the Filipino independence movement, led by Emilio Aguinaldo, between 1899-1903. Perhaps the least remembered of all U.S. wars today, at the time it was widely debated and cost the lives of more than 100,000 Filipinos and 4,200 Americans. Press reports of atrocities committed by American troops--the burning of villages, torture of prisoners of war, and rape and execution of civilians--tarnished the nation's self-image as liberators.

The Anti-Imperialist League

A diverse union of writers (including the famous author, Mark Twain), businessmen, and social reformers opposed to American imperialism, and particularly the annexation of the Philippines. Their reasons for opposition to imperialism differed wildly: some believed that imperialism ran counter to America's core values as a nation (self-determination, freedom, equality, democracy); some believed that American energies should be directed at home not abroad and that it would be too expensive to maintain overseas outposts; others were simply racists who did not wish to bring non-white populations into the United States. This group reflects the emergence of the debate over the extent to which the U.S. should play a leadership role in world affairs, and this debate continues to the present.

The Foraker Act, 1900

A law that declared Puerto Rico was an "insular territory," distinguishing it from the western territories in the continental United States that entered the union on an equal basis as states, as Thomas Jefferson's "Empire of Liberty" had imagined a century earlier. Puerto Rico's one million inhabitants were defined as citizens of Puerto Rico, not the U.S., and denied a future path to statehood. Congress would later extend U.S. citizenship, but not statehood, to Puerto Ricans in 1917. Puerto Rico remains "the world's oldest colony," poised on the brink of statehood or independence. It elects its own government but lacks a voice in the U.S. Congress.

The Insular Cases, 1901-1904

A series of cases between 1901 and 1904 in which the Supreme Court ruled that constitutional protection of individual rights did not fully apply to residents of "insular" territories acquired by the United States in the Spanish-American War, such as Puerto Rico and the Philippines.

The Panama Canal

Roosevelt engineered the separation of the northernmost province from the rest of Columbia in order to facilitate the construction of a canal linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans in order to facilitate the movement of naval and commercial vessels between the two oceans. In 1903, when Colombia refused to cede land for the project, Roosevelt helped to set in motion an uprising by conspirators. Upon establishing Panama's independence, Panama signed a treaty giving the U.S. both the right to construct and operate a canal and sovereignty over the Canal Zone, a ten-mile-wide strip of land through which the route would run. A remarkable feat of engineering, the canal was the largest construction project in history to that date. When completed in 1914, the canal reduced the sea voyage between the East and West Coasts of the U.S. by 8,000 miles. Because of the aggressive manner in which TR initiated the canal, it remained a source of tension with Latin America until President Carter negotiated treaties in 1977 that would return control of the canal zone to Panama. The acquisition of the Panama Canal Zone remains a classic example of realism in U.S. foreign policy.

The Roosevelt Corollary

President Theodore Roosevelt announced, in what was essentially an expansion of the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, that the U.S. had the right to exercise "an international police power" in the Western Hemisphere. It effectively began a period in which the U.S. regarded Latin American to be its "sphere of influence" in which the U.S. actively intervened in the affairs of many Latin American nations to advance the economic and strategic interests of the United States (realism).

World War One (aka the "Great War)

The most devastating war up to that point in human history (killing an estimated ten million soldiers and millions more civilians), lasting from 1914-1919, fought between "the Allies" (Britain, France, Russia, Japan, and eventually the U.S) and the "Central Powers" (Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire). Sparked by the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, its longer term causes included the industrial revolution and the scramble by European nations for colonial possessions overseas and a shifting set of alliances seeking military domination within Europe. The war dealt a severe blow to the optimism and self-confidence of Western civilization, and it sparked many important social, economic, and political changes within the U.S.

The Lusitania

A British passenger ship (which was also carrying a large cache of arms) that German submarines sunk in 1915 off the coast of Ireland, killing over one thousand British passengers, including 124 Americans. When WWI had broken out the prior year, Wilson had proclaimed U.S. neutrality (and thus the right for Americans to travel freely in the Atlantic and to trade with other countries). But Britain had declared a naval blockade of Germany, and Germany launched submarine warfare against ships entering and leaving British ports (of which the Lusitania was one). The sinking of the Lusitania outraged American public opinion and strengthened the hand of those who believed that the U.S. must prepare for possible entry into the war.

The Zimmerman Telegram

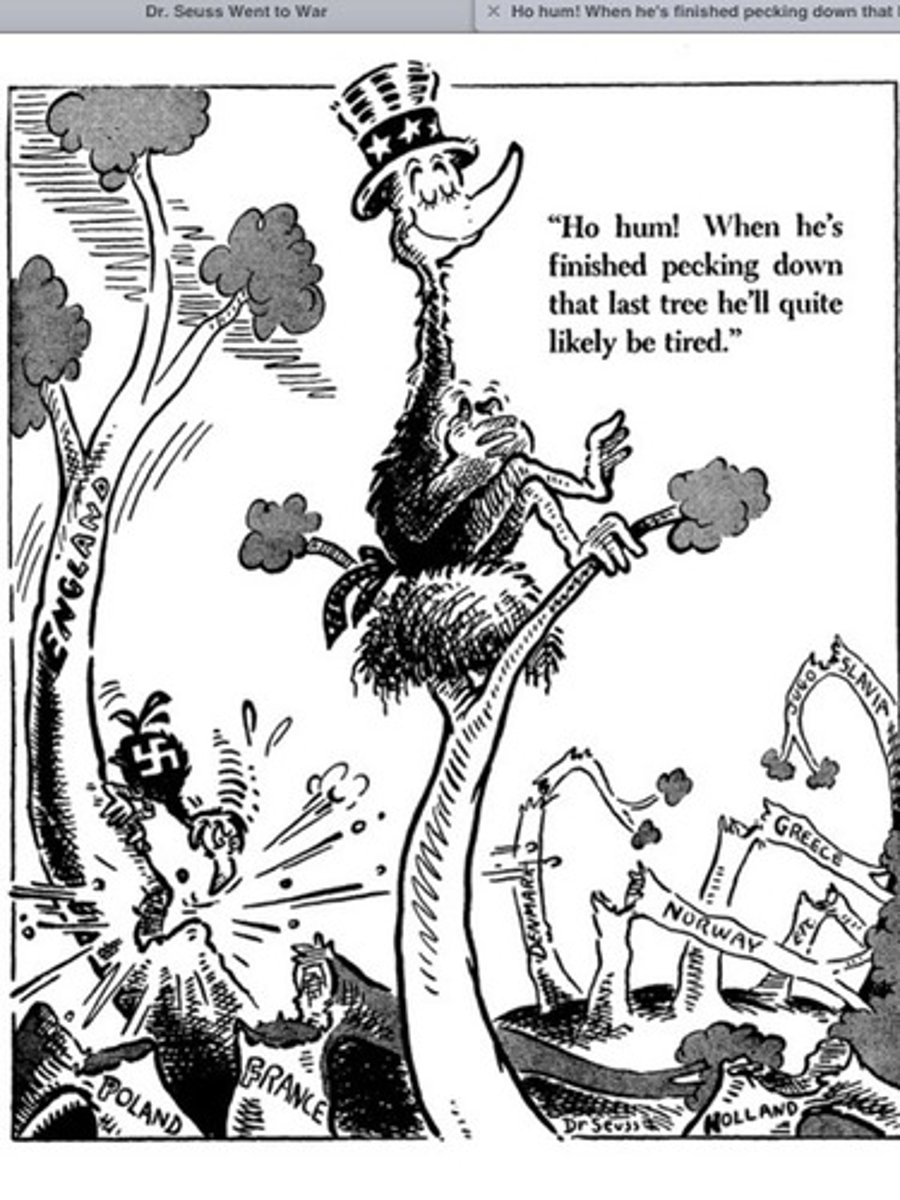

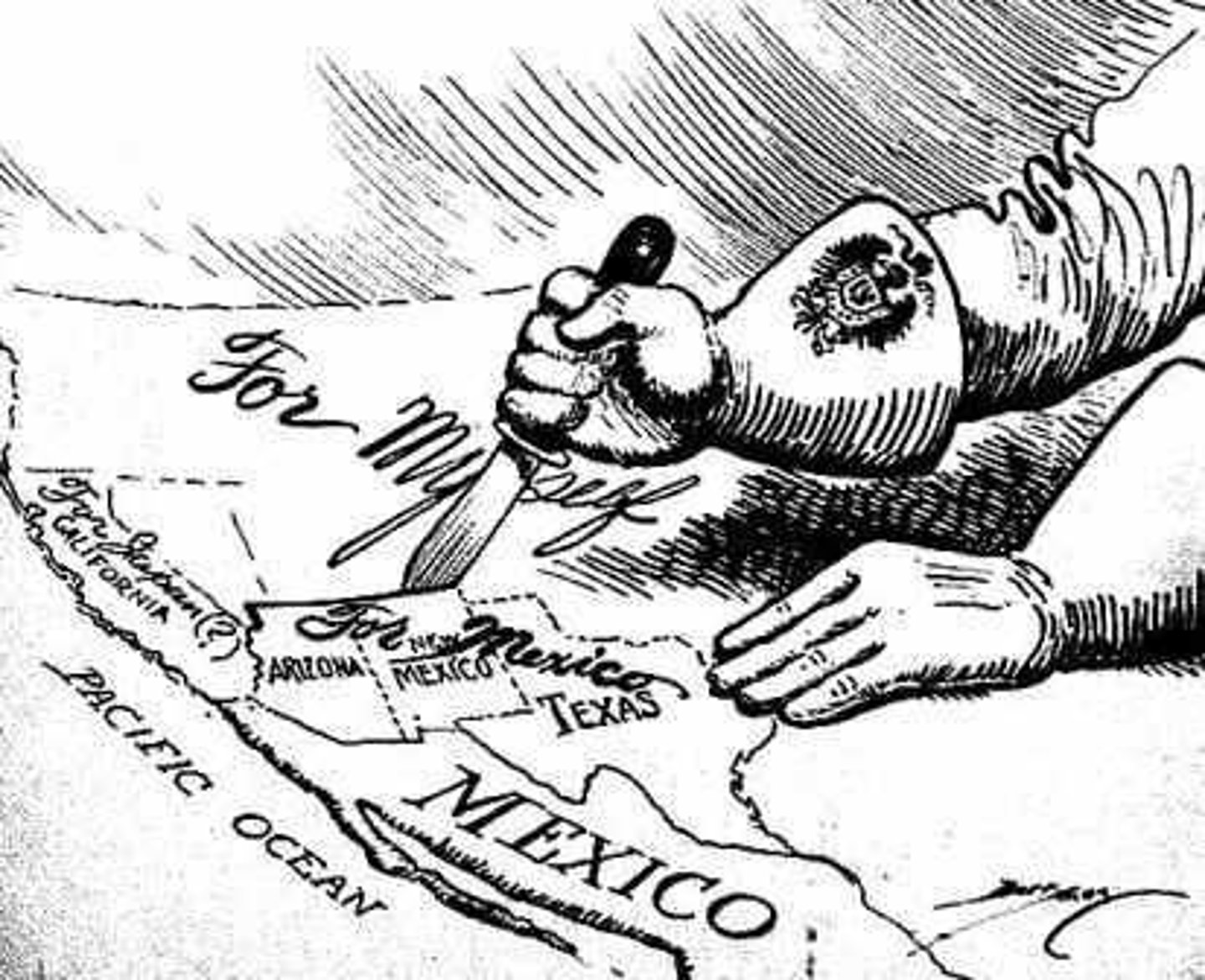

A 1917 message to Mexico from German foreign secretary Arthur Zimmerman asking Mexico to join Germany in a coming war against the U.S., if the U.S. entered WWI on the side of the Allies, and promising in exchange that Germany would help Mexico recover the territory it lost in the Mexican-American War of 1846-48. The message was intercepted by British spies and made public, further outraging Americans and contributing to the U.S. entrance into WWI on the side of the Allies.

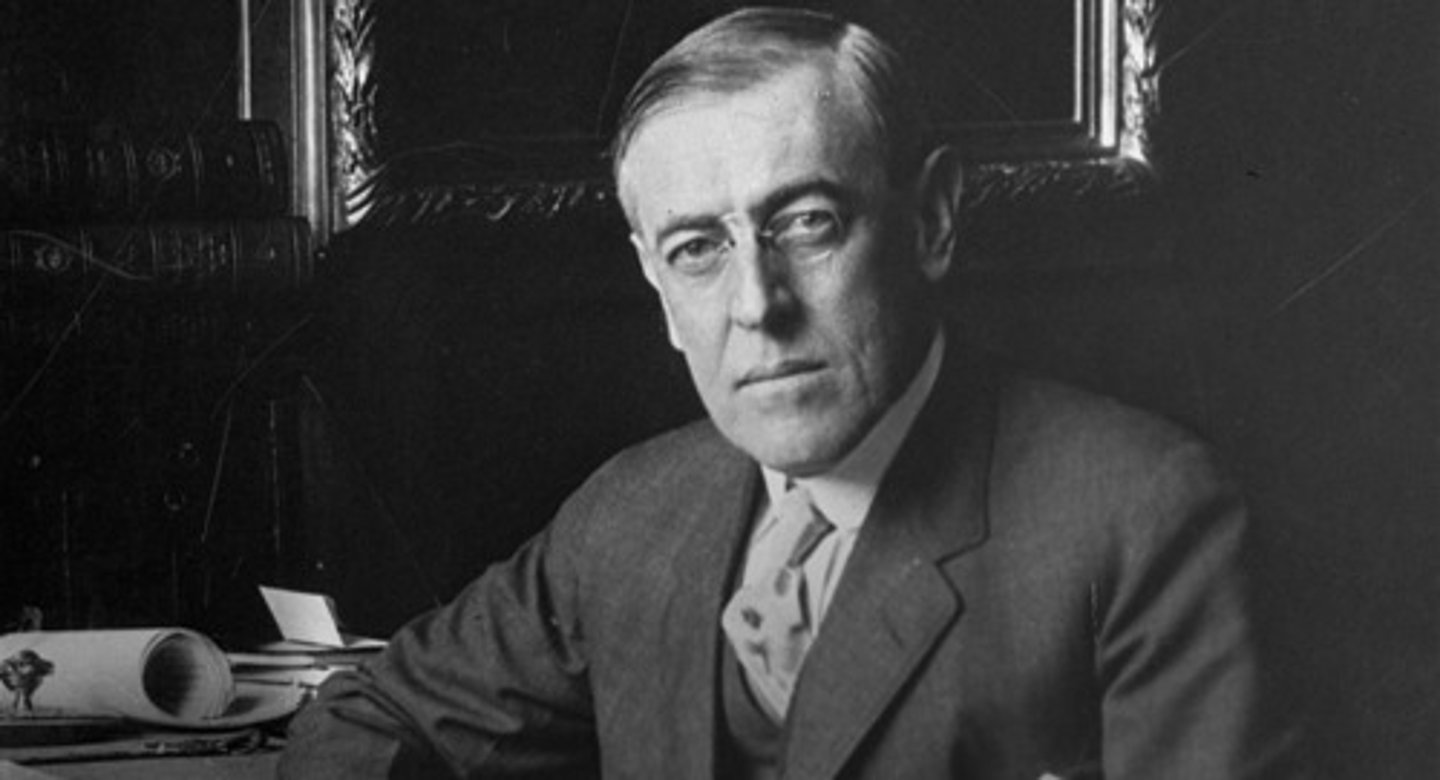

The Fourteen Points

The clearest statement of U.S. objectives during WWI, and President Wilson's vision for the post-WWI international order. Among them key principles were self-determination for all nations, freedom of the seas, free trade, open diplomacy (an end to secret treaties), the readjustment of colonial claims with colonized people give "equal weight" in deciding their futures, and the creation of a "general association of nations" to preserve the peace (soon to become the "League of Nations"). Although purely an American program, not endorsed by the other Allies, the Fourteen Points established the agenda for the Paris Peace Conference that followed the war.

The War Industries Board, and the War Labor Board

Two World War One era agencies that, albeit temporarily, contributed to the creation of a national state with unprecedented powers and sharply increased presence in Americans' everyday lives. The first (the WIB) promoted efficiency through presiding over all elements of war production from the distribution of raw materials to the prices of manufactured goods. The second (the WLB) pressed for the establishment of a minimum wage, eight-hour workday, and the right to form unions. These agencies saw themselves as partners of business as much as regulators. They guaranteed government suppliers a high rate of profit and encouraged cooperation among former business rivals by suspending antitrust laws. Many progressives hoped to see the wartime apparatus of economic planning continue after 1918. The Wilson administration, however, quickly dismantled the agencies that had established controls over industrial production and the labor market, although during the 1930s they would serve as models for some of the policies of FDR's New Deal.

Selective Service Act of 1917

To raise a national army for U.S. entry into World War, this act authorized the government to raise a national army through the compulsory enlistment of people. It required all men ages 21-30 (which included 24 million men at that time) to register with the draft board. The army soon swelled from 120,000 to 5 million men.

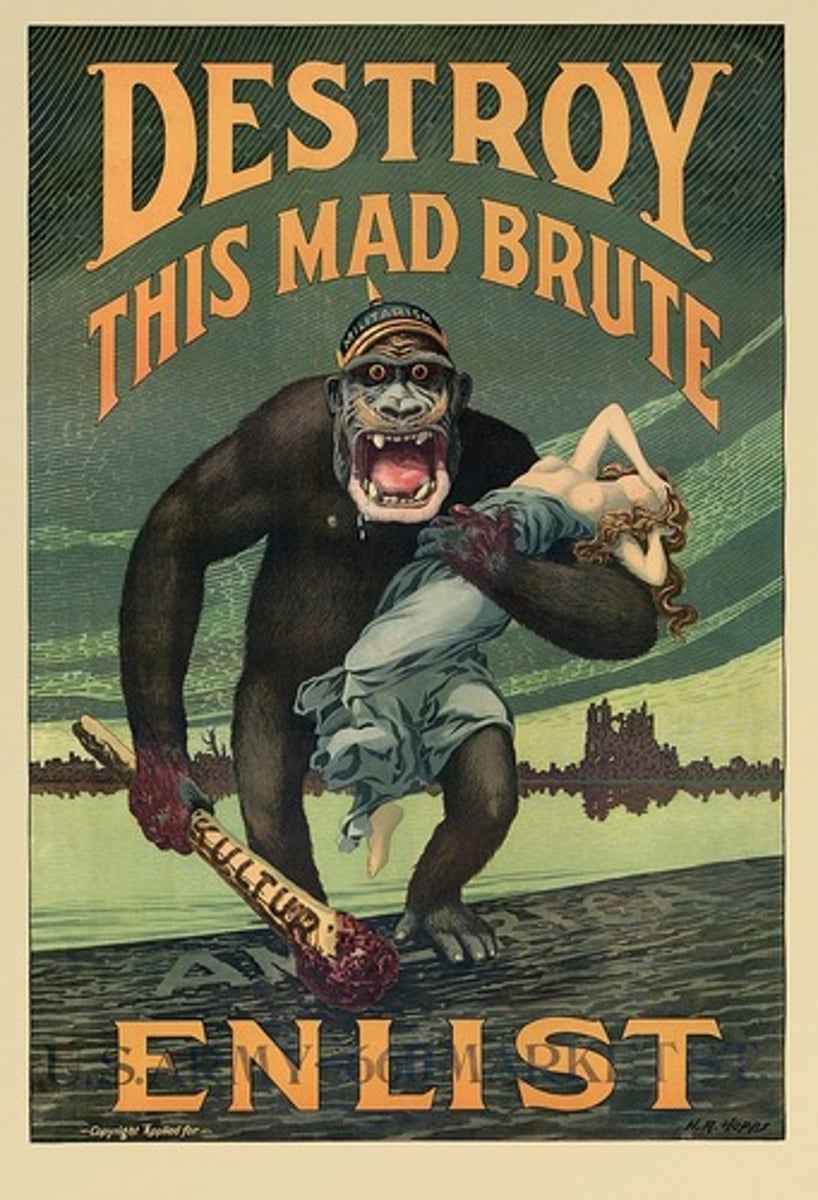

The Committee on Public Information (CPI)

Directed by George Creel, this was a government agency created in 1917 to influence public opinion in regards to World War One. Enlisting academics, journalists, artists, and advertising men, this agency dispatched "Four-Minute Men" to give pro-war speeches to audiences in schools, theaters, and other public venues, and it flooded the country with pro-war propaganda using every available medium from pamphlets, posters, newspaper ads, and motion pictures.

Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party

This suffragette and her organization was composed of a new generation of college-educated American activists who pressed for the right to vote with militant tactics that many older suffrage advocates found scandalous. She and her party used WWI to point out U.S. hypocrisy: "How could the country fight for democracy abroad while denying it to women at home?" They chained themselves to the White House fence, resulting in a seven-month prison sentence. They began a hunger strike in prison and were force fed raw eggs through a tube. The combination of women's patriotic service in the war effort as well as widespread outrage over the mistreatment of Paul and her fellow prisoners pushed the Wilson administration towards full-fledged support for woman suffrage. The Nineteenth Amendment was ratified in 1920.

The Nineteenth Amendment

Ratified in 1920, this Amendment stated,"The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex." It was the culminating victory of the seventy-two year long woman suffrage movement, which began at the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848.

The Prohibition Movement

Inherited from the 19th century, this movement to ban intoxicating alcoholic beverages gained new strength and militancy during Progressive Era and finally achieved national success during WWI with the ratification of the 18th Amendment. A number of impulses fueled the movement: Employers hoped it would create a more disciplined labor force; Urban reformers believed it would promote a more orderly city environment and undermine urban political machines that used saloons as places to organize; Women reformers hoped it would protect wives and children from husbands who engaged in domestic violence when drunk or who squandered their wages at saloons; and Native protestants saw it as a way of imposing "American" values on immigrants.

The Eighteenth Amendment

Ratified in 1919 (and taking effect in 1920) this amendment declared the production, transport, and sale of alcohol (though not the consumption or private possession) illegal. The separate Volstead Act set down methods for its enforcement and defined which "intoxicating liquors" were prohibited, and which were excluded from prohibition (e.g., for medical and religious purposes).

World War One had made beer seem unpatriotic since many prominent breweries were owned by German-Americans. And the recent passage of the Sixteenth Amendment (1913), which authorized a national income tax, had made prohibition economically viable by providing the national government with a significant new source of revenue that could replace taxes on alcohol. The 21st Amendment, ratified in 1933, repealed the 18th Amendment.

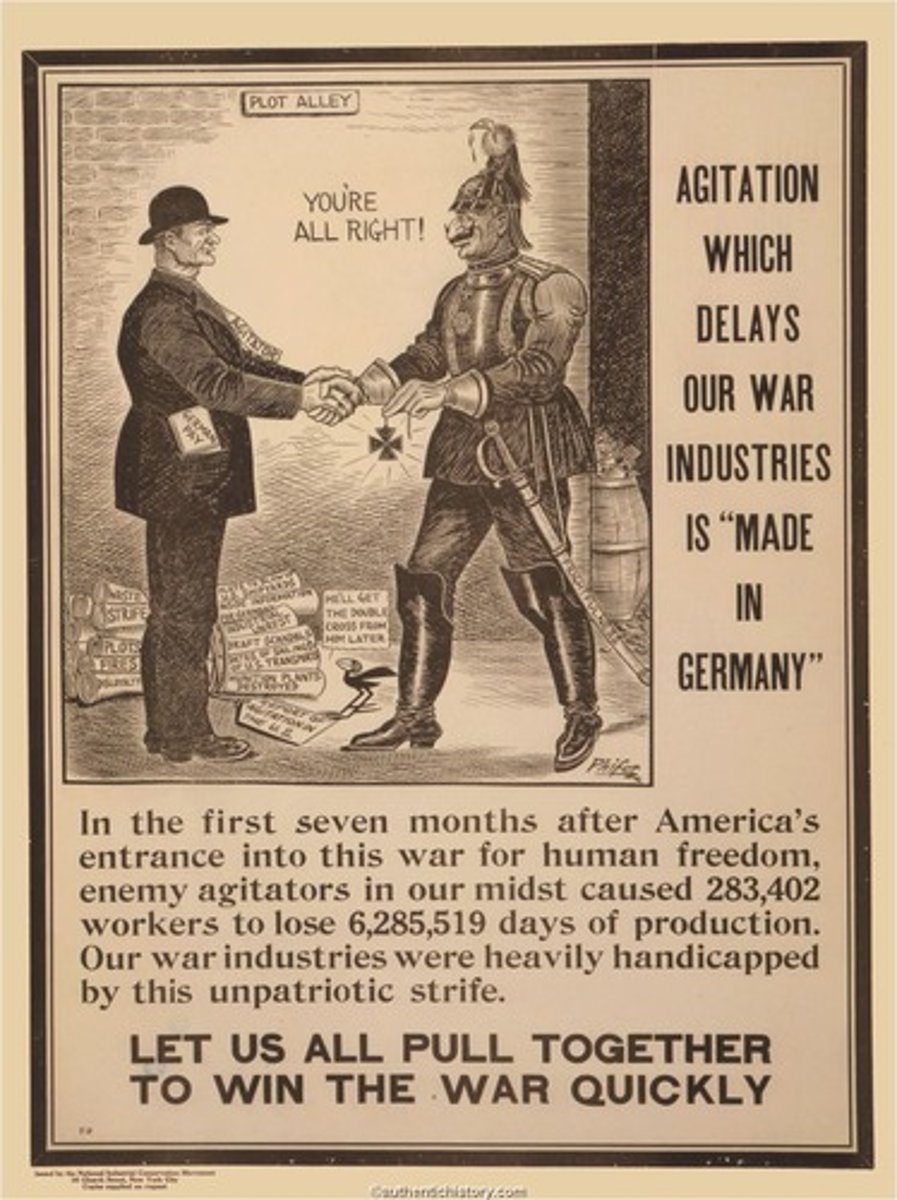

The Espionage and Sedition Acts of 1917-18

Laws enacted during WWI that restricted the freedom of speech. The first prohibited not only spying and interfering with the draft but also "false statements" that might impede military success. The postmaster general barred from the mails numerous newspapers and magazines critical of the administration, which included virtually the entire socialist press as well as many foreign-language publications. The second act made it a crime to make spoken or printed statements that intended to cast "contempt, scorn, or disrepute" on the "form of government," or that advocated interference with the war effort. The government charged more than 2,000 persons with violating these laws, including Eugene Debs for delivering an anti-war speech. Debs, the famous American socialist and labor union leader, was sentenced to ten years, ran for president from prison in 1920 (receiving 900,000 votes), and had his sentence commuted in 1921.

"Coercive patriotism" during WWI

Many incidents of extreme, and sometimes violent, repression took place during WWI as government and private groups, like the American Protective League, came to equate patriotism with support for the government, the war, and the American economic system while antiwar sentiment, labor radicalism, and sympathy for the Russian Revolution became "un-American."

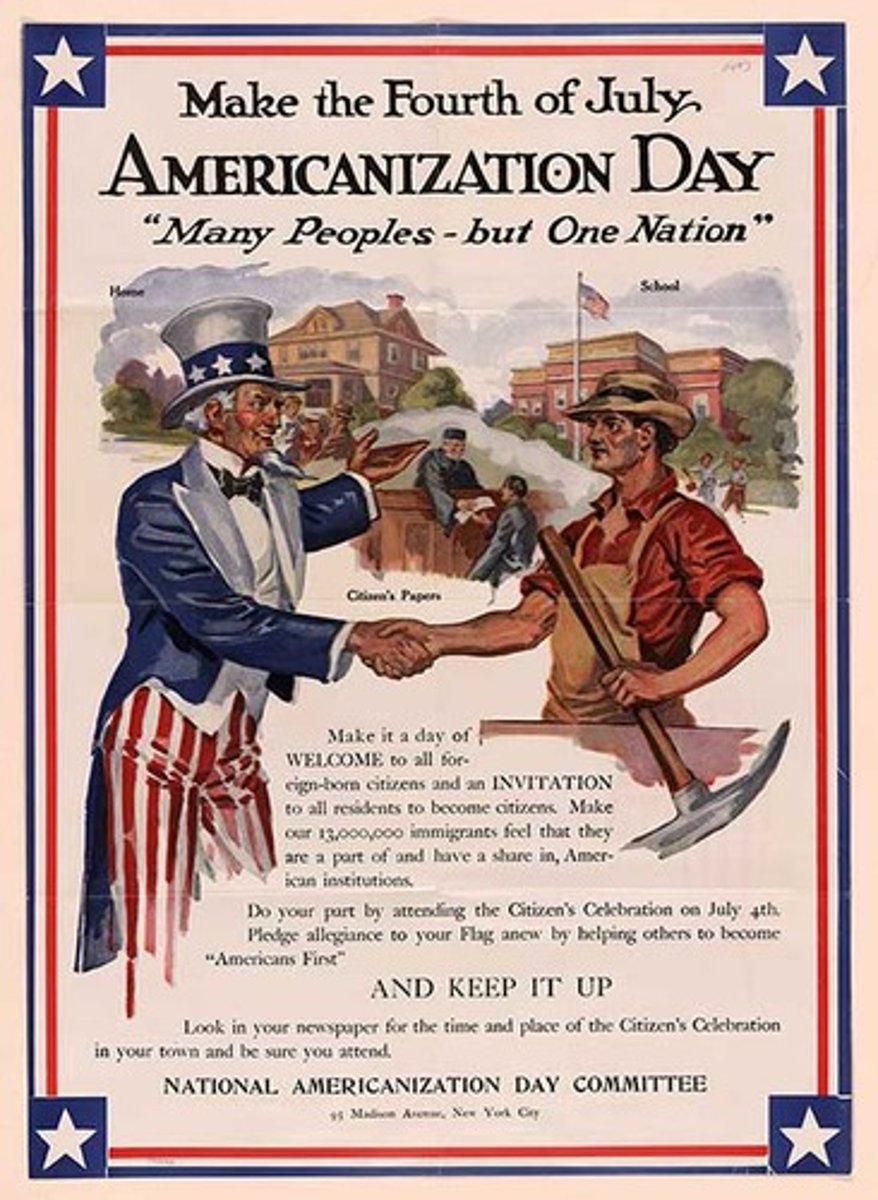

"Americanization" during WWI

This term refers to widespread efforts during WWI to create a more homogeneous national culture. The "melting pot" became a popular concept by which newcomers were supposed to merge their identity into existing American nationality. Public and private groups of all kinds--including educators, employers, labor leaders, social reformers, and public officials--took up the task of Americanizing new immigrants.

A minority of Progressives questioned and critiqued these efforts. Randolph Bourne, for example, pointed out that "there is no distinctive American culture," and instead envisioned a democratic, cosmopolitan society in which immigrants and natives alike submerged their group identities in a new "trans-national" culture.

The Anti-German Crusade

As the largest population descending from America's wartime enemy, German-Americans bore the brunt of forced Americanization during WWI. States and patriotic organizations enacted made many efforts to restrict German music, German culture, and the use of the German language. Even popular words of German origin went out of favor ("hamburger"="liberty sandwich").

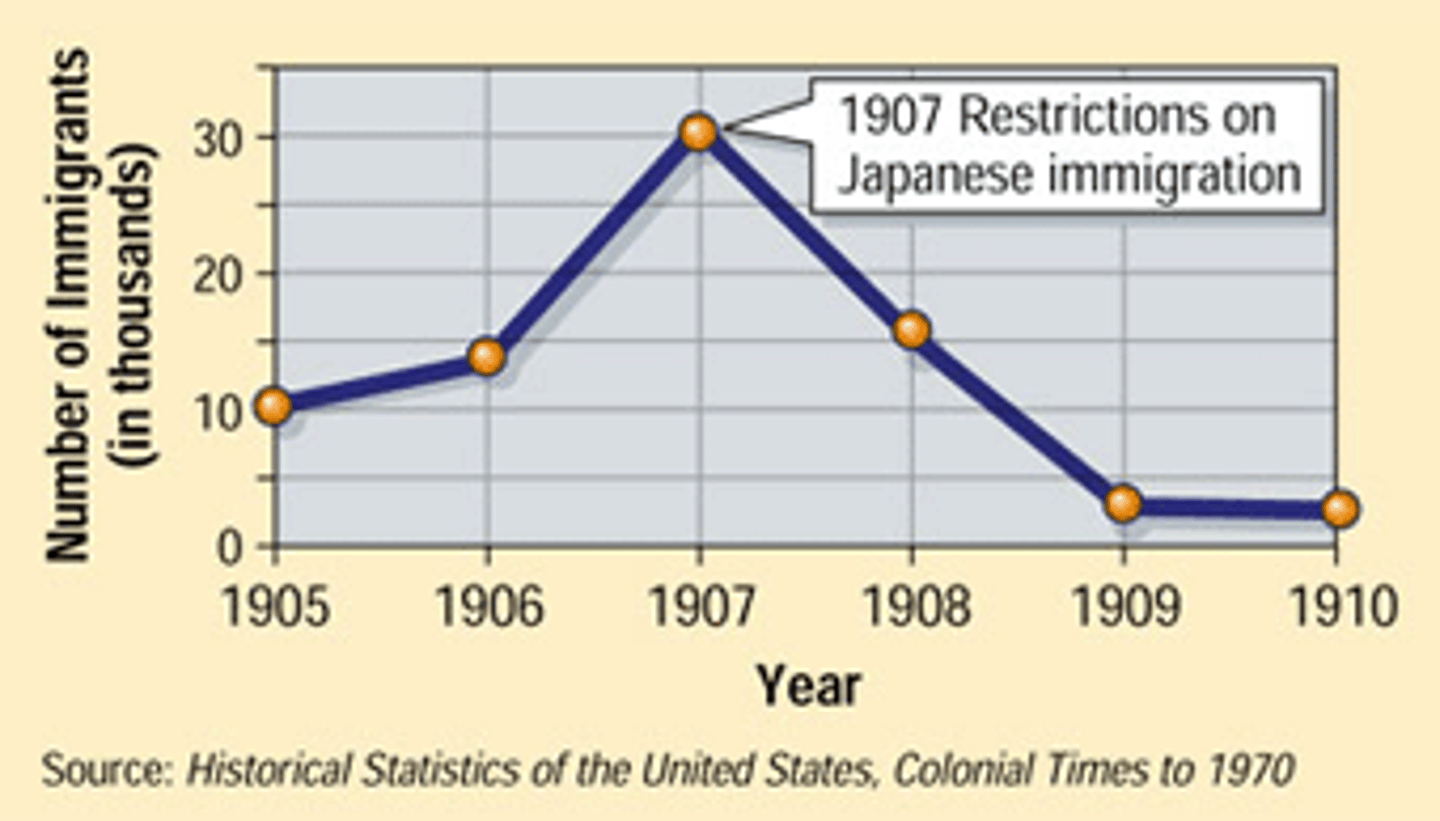

The Gentleman's Agreement of 1907

An informal agreement between President Teddy Roosevelt and the government of Japan whereby the United States of America would not impose restrictions on Japanese immigration, and Japan would not allow further emigration to the U.S.. The goal was to reduce tensions that had arisen between the two countries over the treatment of Asian Americans in West Coast cities like San Francisco. This agreement was an example of how non-whites confronted ever-present boundaries of exclusion during the era when "Americanization" and the "melting pot," no matter how coercive, allowed immigrants from Europe and their children to eventually adjust to the conditions of American life, embrace American ideals, and become productive citizens enjoying the full blessings of American freedom.

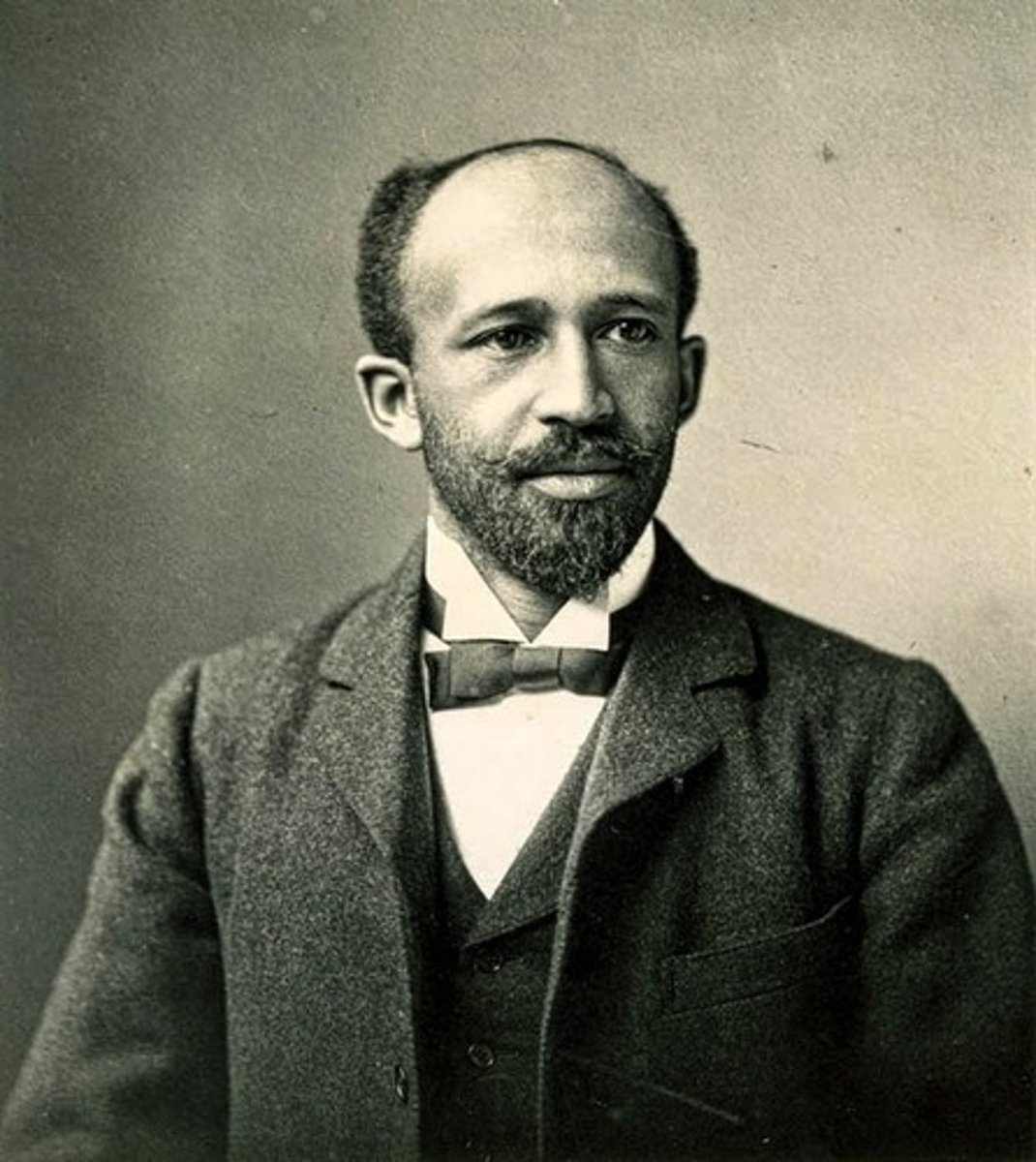

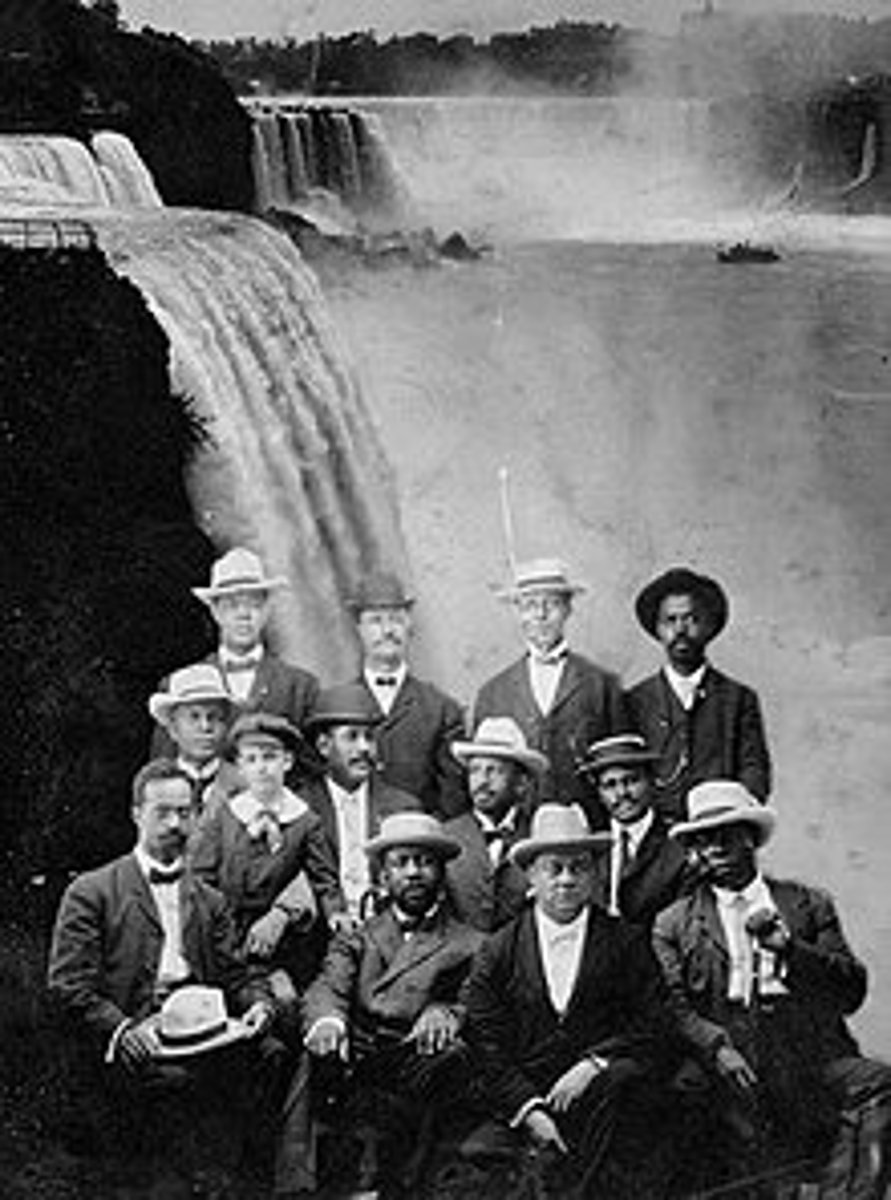

W. E. B. Du Bois

Born in Massachusetts in 1863, this prominent black scholar and activist was the first African American to earn a doctorate from Harvard, authored The Souls of Black Folk (1903)--which challenged the accommodationist policies of Booker T. Washington and called for equal social and political rights--and founded the Niagara Movement and the NAACP. He believe that educated African Americans like himself--the "talented tenth" of the black community--must use their education and training to challenge racial inequality. Typical of other Progressives of the era, he believed investigation, exposure, education, and agitation would lead to solutions for social programs.

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)

Civil Rights organization started in 1909 (growing out of the Niagara Movement) and founded by W. E. B. Du Bois. It was a bi-racial organization aimed at advancing justice for African Americans. In contrast to Booker T Washington's gradualism and economic focus, this organization primarily adopted a legal strategy of challenging Jim Crow laws in court with the goal of securing equal political and social rights for African Americans as soon as possible.

The Great Migration

A large-scale migration of African Americans from the South to the North during the WWI Era (half a million between 1910-1920). Harsh Jim Crow laws, the threat of lynching, and limited opportunities in the South acted as "push factors;" some historians consider these migrants to be "refugees" from the racial terrorism of the South. "Pull factors" in the North included the promise of more freedom, better education, and the higher wages offered by Northern factories contributing to wartime military production. During WWI, many factory jobs became available in in Northern cities due to previous employees entering the military, the drastic reduction of immigrants from Europe, and the increased demand for the production of war materials. Yes the migrants encountered vast disappointments; severely restricted employment opportunities, exclusion from unions, rigid housing segregation, and outbreaks of violence that made it clear that no region of the country was free from racial hostility.

The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921

High levels of racial violence, mostly targeting blacks, marked the WWI Era in the U.S.; more than 250 people died in riots in the North in 1919, and 76 blacks were lynched in the South in 1920. But this worst race riot in U.S. history. More than 300 blacks were killed and over 10,000 left homeless after a white mob, including police and National Guardsmen, burned an all-black section of the city to the ground. The violence erupted after a group of black veterans tried to prevent the lynching of a youth who had accidentally tripped and fallen on a white female elevator operator, causing rumors of rape to sweep the city.

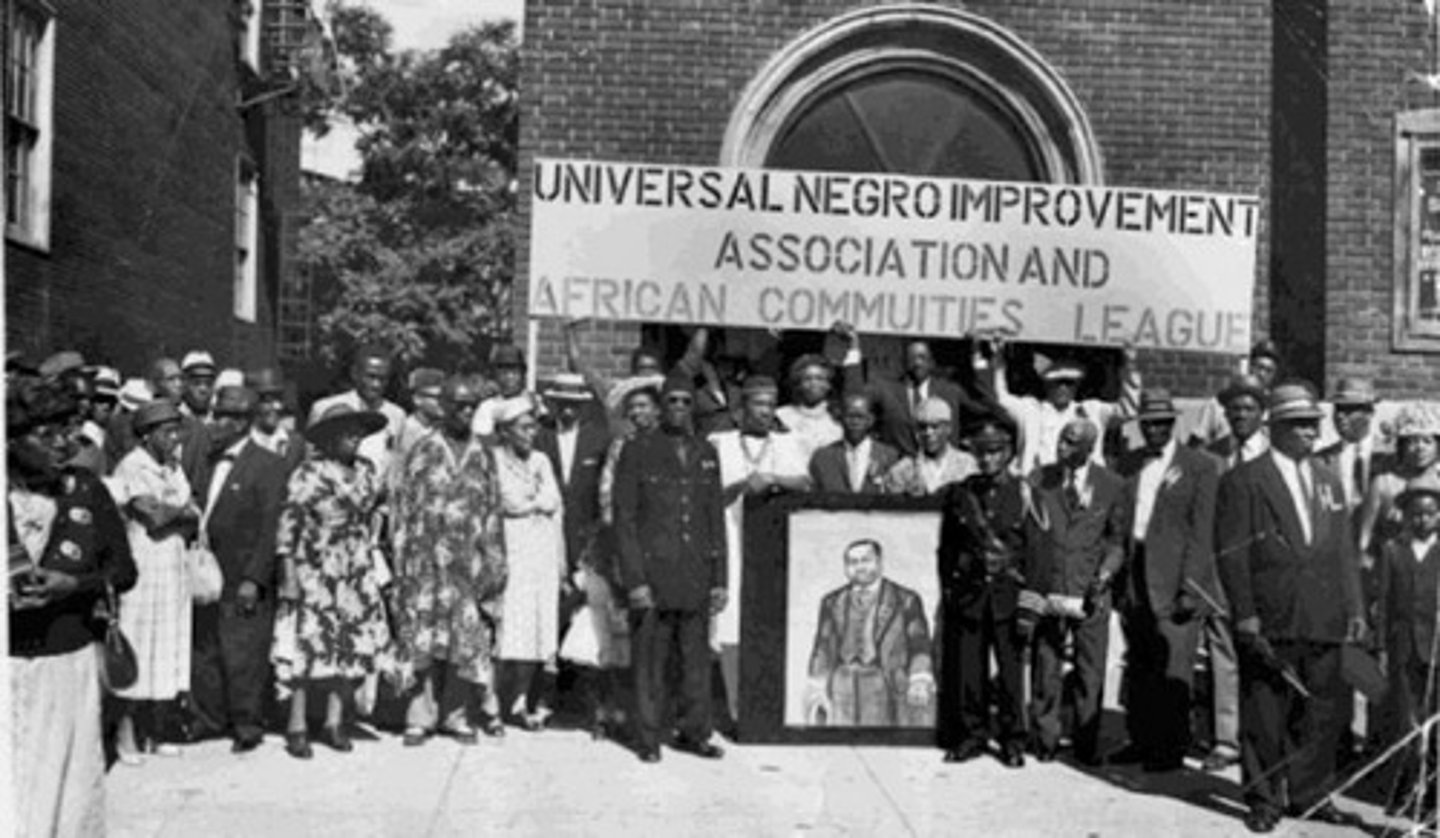

Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association

A proponent of black nationalism and a recent immigrant to New York City from Jamaica, this leader was at the forefront of a popular movement for African independence and black self-reliance (also called Pan-Africanism) in the 1920s, which reflected the new spirit of militancy among blacks. Freedom for Garveyites meant national self-determination (not integration). Blacks, they insisted, should enjoy the same internationally recognized identity enjoyed by other peoples in the aftermath of WWI. He also founded the Black Star Line, a shipping and passenger line which promoted the return of the African diaspora to their ancestral lands. Although most American black leaders condemned his methods and his support for racial segregation, he attracted a large following. By 1922, the Black Star Line had gone bankrupt, he served five years in prison for mail fraud, and he was deported to Jamaica in 1927. His movement then rapidly collapsed.

The Great Steel Strike of 1919

In 1919, at the end of a war more than 4 million workers engaged in strikes--the greatest wave of labor unrest in American history. But this, the largest labor uprising of the era, was centered in Chicago, and united some 365,000 mostly immigrant workers in demands for union recognition, higher wages, and an eight-hour workday. In response to the strike, leaders of the steel industry launched a concerted counterattack. Playing into the Red Scare that swept the nation, employers appealed to anti-immigrant sentiment among native-born workers and conducted a propaganda campaign that associated the strikers with the IWW, communism, and disloyalty. Middle class opinion turned against the labor movement, the strike collapsed in early 1920.

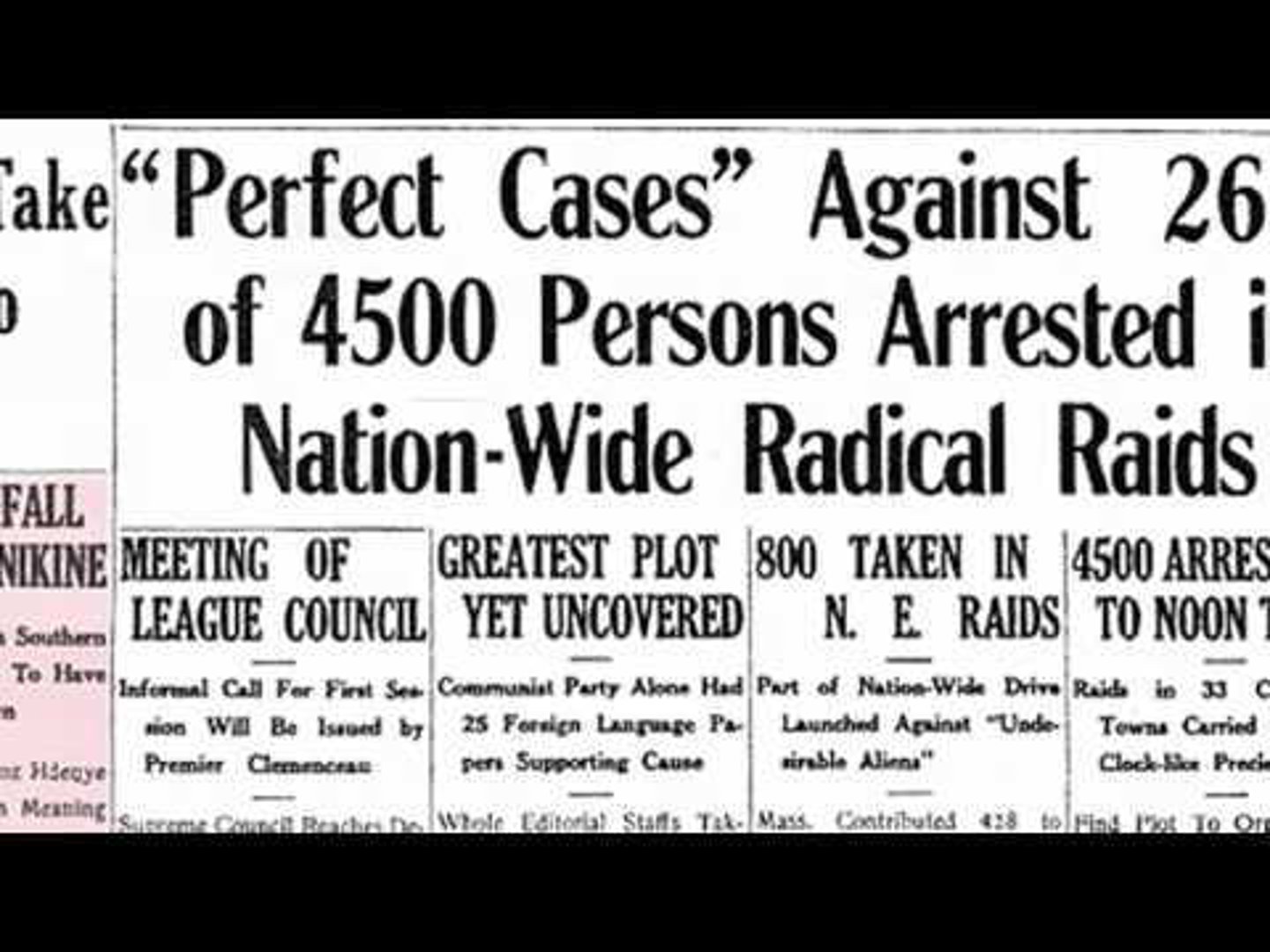

The (First) Red Scare and the Palmer Raids

Wartime repression of dissent continued after WWI and reached its peak in 1919-1920. This was a short-lived but intense period of political intolerance inspired by the post war strike wave and the social tensions and fears generated by the Russian Revolution.

Convinced that episodes like the steel strike of 1919 were part of a worldwide communist conspiracy, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer dispatched federal agents to raid the offices of radical and labor organizations throughout the country. More than 5,000 people were arrested, most of them without warrants, and held for months without charge. The government deported hundreds of immigrant radicals, including Emma Goldman, and began keeping files on thousands of Americans suspected of holding radical political ideas.

The abuse of civil liberties in the early 1920s was so severe that that Palmer came under heavy criticism from Congress and much of the press. The reaction planted the seeds for a new appreciation of the importance of civil liberties that would begin to flourish in the 1920s. But in their immediate impact, the events of 1919-1920 dealt a devastating setback to radical and labor organizations of all kinds and kindled and intense identification of patriotic Americanism with support for the political and economic status quo.

Treaty of Versailles

The 1919 peace conference outside of Paris, France, where leaders of the Allied powers and Germany negotiated an end to World War One. Among the provisions of treaty, the League of Nations was established, and self-determination was applied to eastern Europe (but not elsewhere). But the treaty was much harsher than Wilson wanted, and it virtually guaranteed future conflict in Europe by limiting the size of the German military, declaring Germany morally responsible for the war, and saddling Germany with astronomical reparations payments that crippled the German economy.

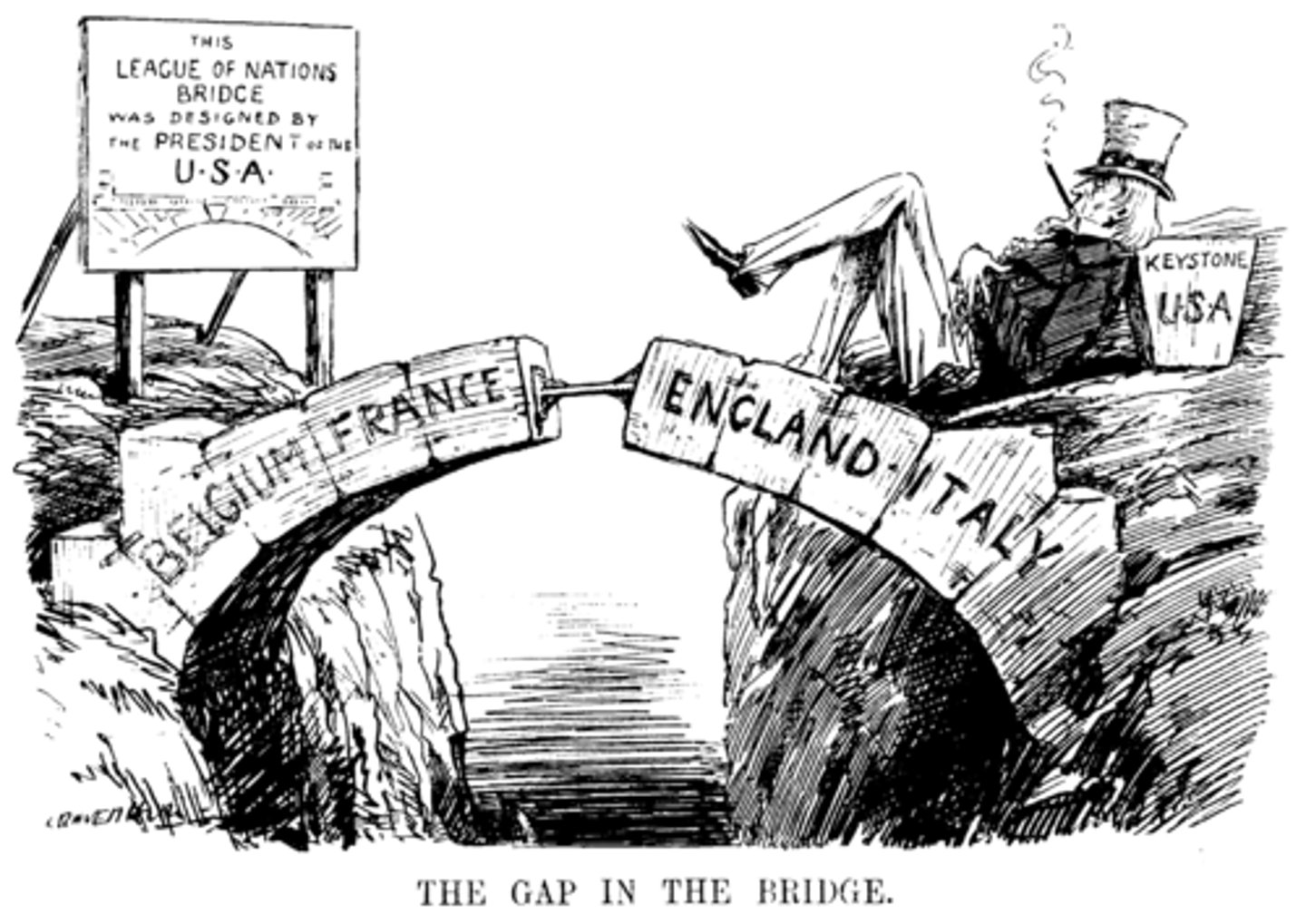

The debate over the League of Nations

Established by the Treaty of Versailles, this international organization's principal mission was to maintain world peace through collective security, disarmament, and settling international disputes through negotiation and arbitration, and each member nation had one one vote in the Assembly.

This represented a fundamental philosophical shift in world diplomacy from the previous one hundred years. Wilson envisioned the League of Nations as a kind of global counterpart to the regulatory commissions Progressives had created at home to maintain social harmony and prevent the powerful from exploiting the weak (Thus, he said, WWI would be "the war to end all wars" and the war "to make the world safe for democracy"). However, many Americans feared U.S. membership in the League would commit the U.S. to an open-ended involvement in the affairs of other countries, and that the League threaten to deprive the U.S. of its freedom of action. Wilson refused to compromise with "reservationists" who wanted assurances that the obligation to assist League members would against attack did not supersede the power of Congress to declare war, and so the U.S. never joined the League of Nations.

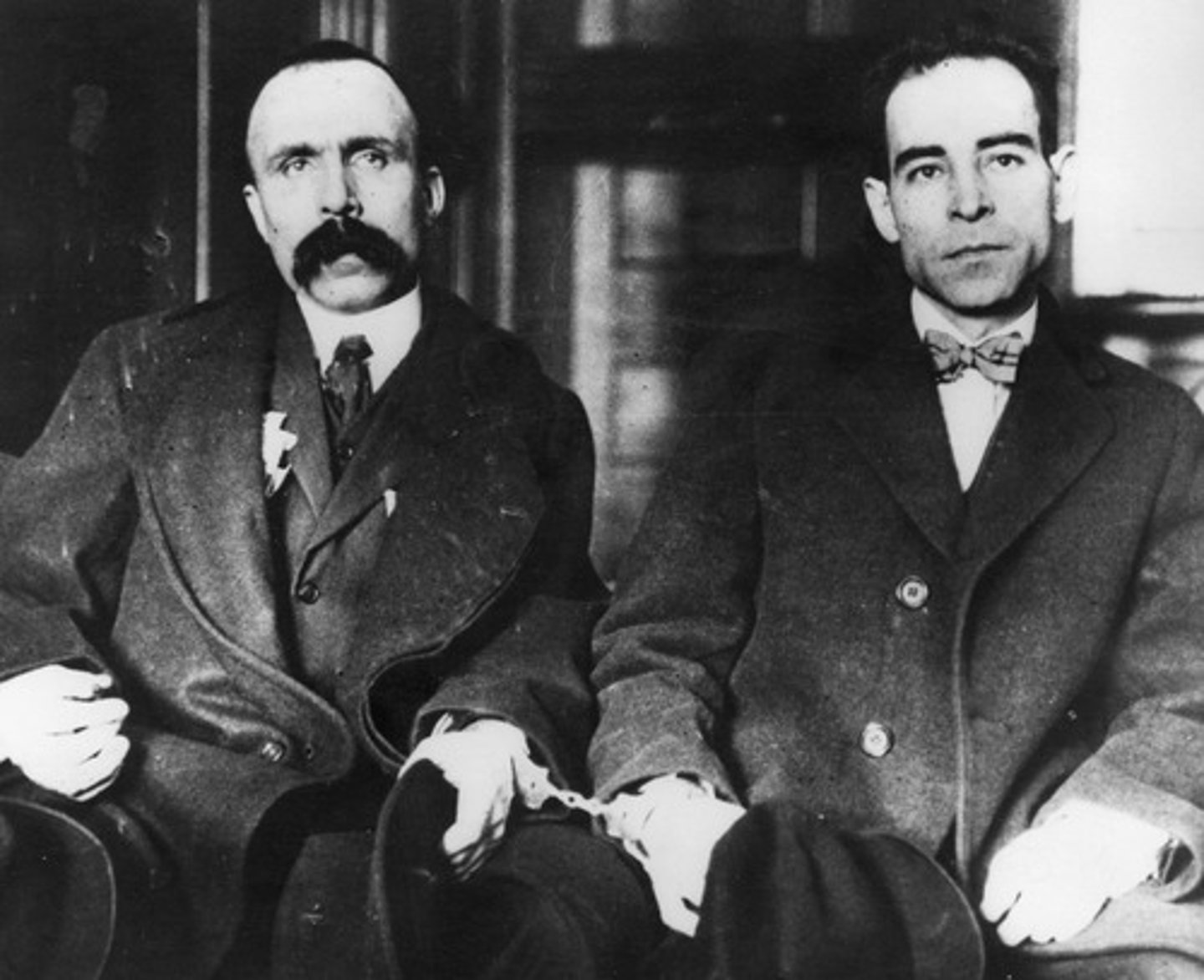

Sacco and Vanzetti

These two Italian immigrants were arrested and accused to participating in a robbery in 1920 in MA. It was the height of the Red Scare, and the two men were anarchists who saw violence as an appropriate weapon of class warfare. Despite the limited and dubious evidence presented against them, in the atmosphere of anti-radical and anti-immigrant fervor, their conviction was a certainty. Their case attracted international attention during a lengthy appeals process, and ultimately a special commission upheld their guilty verdict and their death sentences. While they both died in the electric chair, their case remained controversial and reflected the fierce cultural battles of the 1920s.

Edward Bernays

Often considered "the father of the public relations industry"--an industry that expanded dramatically during the 1920s--he had been a member of the Committee on Public Relations (CPI) during WWI and went on to apply the lessons that the CPI learned about "the conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses" to the world of commercial advertising. His best-known campaigns include a 1929 effort to promote female smoking by branding cigarettes as feminist "Torches of Freedom" and his work for the United Fruit Company connected with the overthrow of the Guatemalan government in 1954.

Flappers

A term that refers to the mostly young and urban women during the 1920s who challenged the gender norms of society by wearing bobbed hair and short skirts, by drinking and smoking in public, and by using birth control unapologetically. These women frequented sexually charged Hollywood films, dance halls, and music clubs where white people now performed "wild" dances like the Charleston that had long been popular in black communities. However, this form of personal freedom was largely a function of lifestyle and consumer choices resulting from the advertising and mass entertainment of the Twenties, and it had little connection to political or economic radicalism of feminists during the Progressive Era.

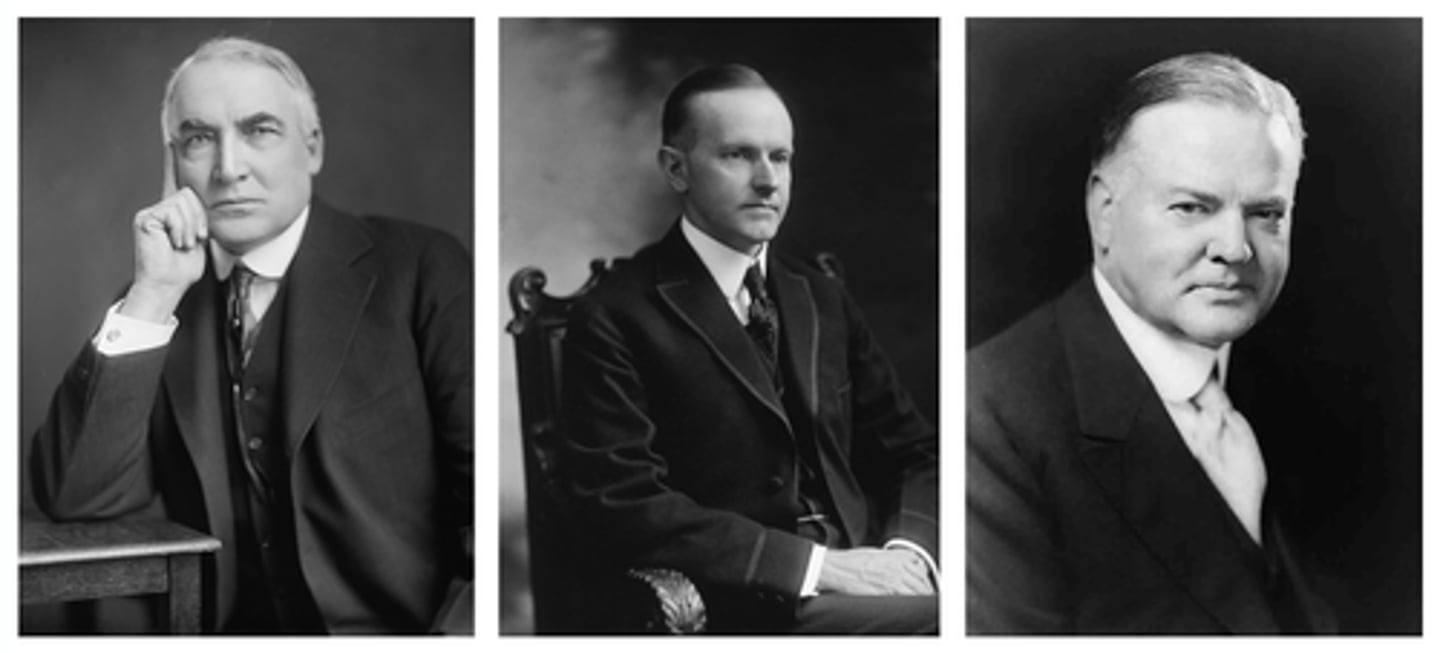

The Republican Era

The term used by political historians to refer to the politics of the 1920s and specifically the Presidencies of Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover; all three were Republicans. Reflecting the interests of business lobbyists, Republicans lowered taxes on personal incomes and business profits, maintained high tariffs, supported employers' continuing campaign against unions, and appointed many pro-business members to government agencies that, Progressives complained, they effectively repealed the regulatory system.

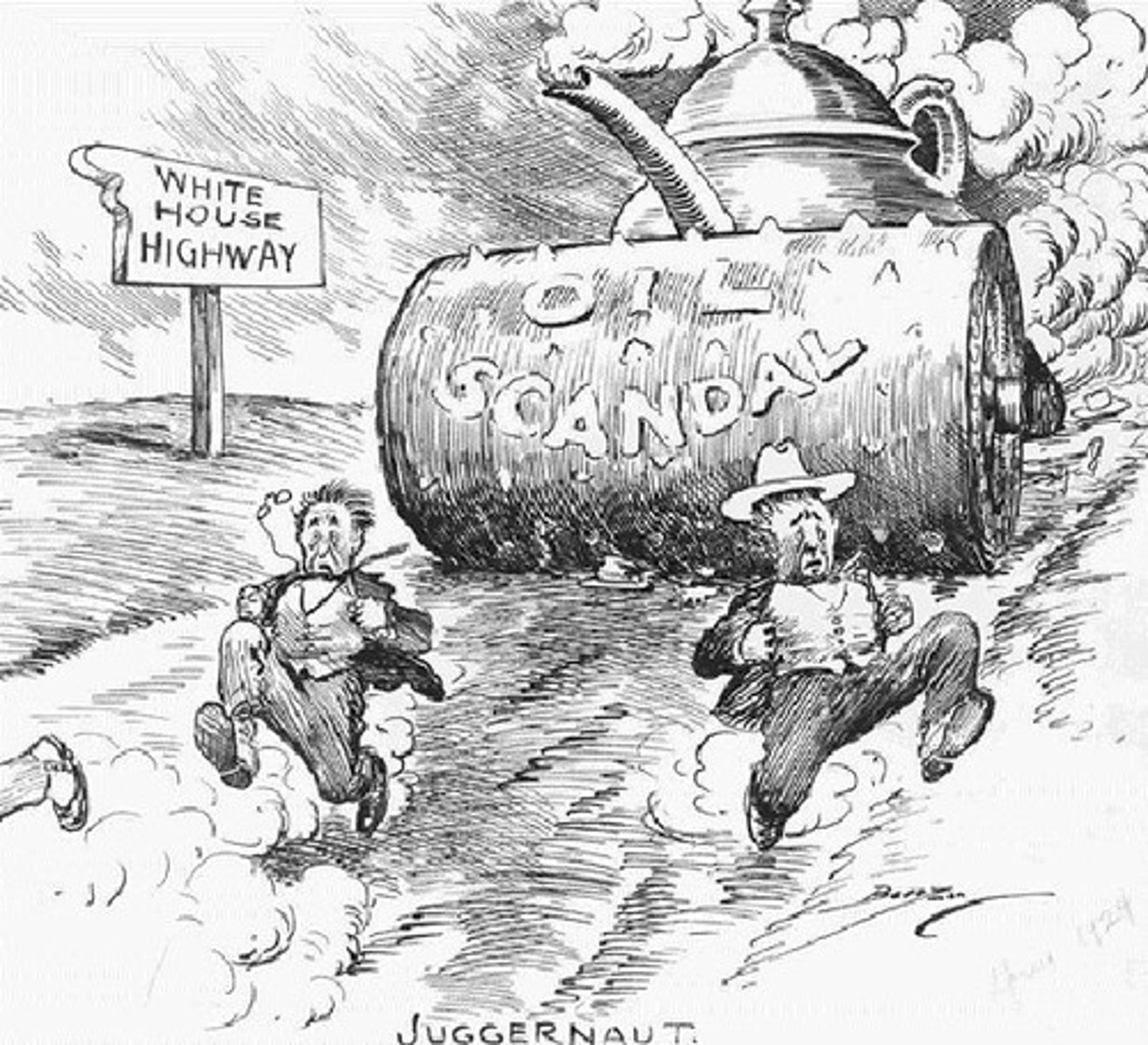

The Teapot Dome Scandal

The biggest scandal of President Warren G. Harding's Presidency, which was one of the most corrupt presidential administrations in U.S. history. Between 1921 and 1922, the Secretary of the Interior, Albert Fall, accepted nearly $500,000 from private businessmen to whom he leased government oil reserves in Wyoming. Fall became the first cabinet member in history to be convicted of a felony.

The Hays Code

A set of self-regulatory moral guidelines that the film industry adopted in 1930 which prohibited movies from depicting nudity, long kisses, and adultery, and barred scripts that portrayed clergymen in a negative light or criminals sympathetically.

The Lost Generation

A group of American writers and poets, both men and women, who immigrated to Europe during the 1920s, in part due to their disillusionment with the conservatism of American politics and the materialism of American culture. It included novelists and poets like Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and T.S. Eliot.

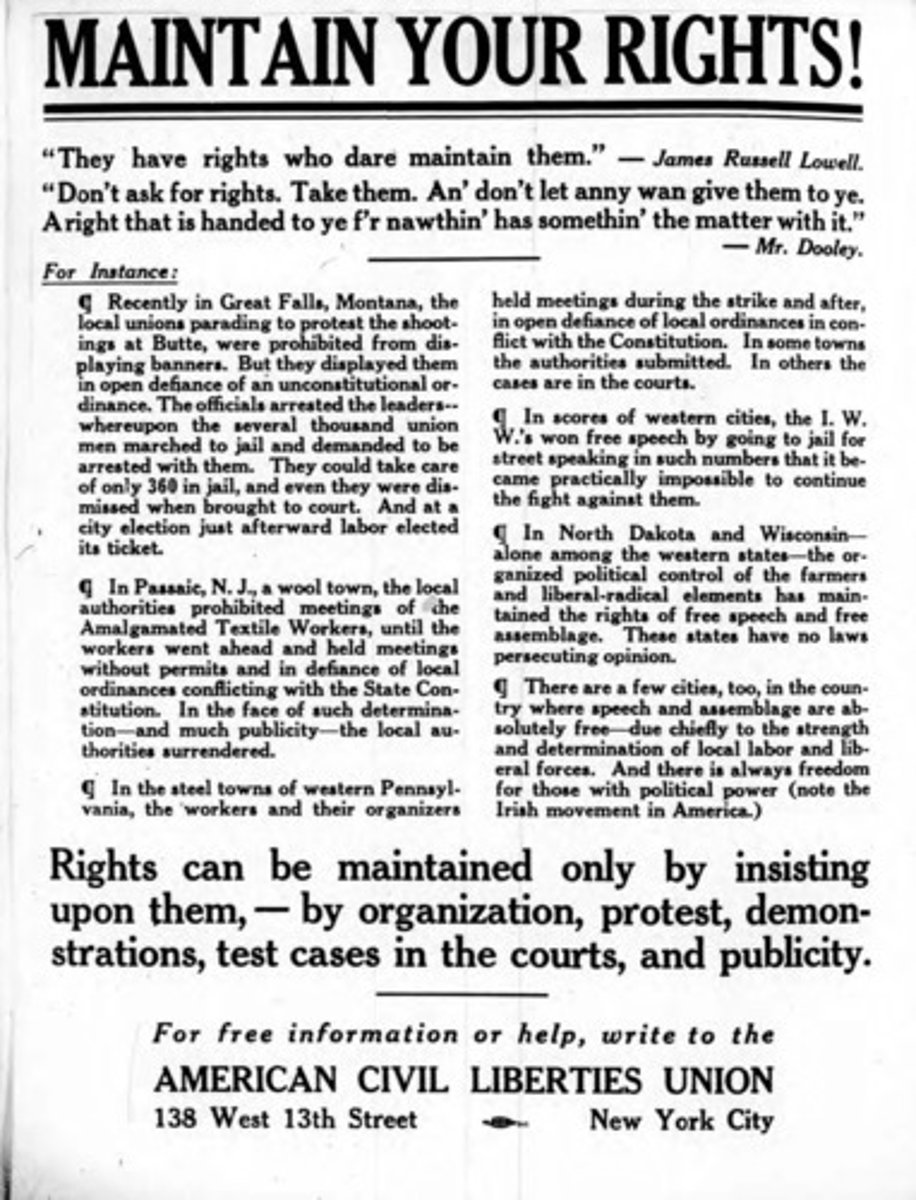

The ACLU (The American Civil Liberties Union)

Formed in 1917 by a small group of pacifists, Progressives, and lawyers who were upset by the the repression of dissenters during WWI, this organization aimed to protect "civil liberties," which are rights an individual may assert even against democratic majorities. For the next century, and beyond, this organization would grow and take part in most of the landmark cases that helped to bring about a "rights revolution." Its efforts helped to give meaning to the traditional civil liberties like freedom of speech and invented new ones, like the right to privacy.

"Clear and Present Danger"

The concept from Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes' opinion in Schenck v. United States (1919) that became the basic test in First Amendment cases for the next half-century. The Schenck case upheld the constitutionality of the Espionage Act and the conviction of Charles Schenck, as socialist who had distributed anti-draft leaflets through the mails during WWI. Holm's concept dealt a devastating blow to the concept of civil liberties.

"Marketplace of ideas"

This is a rationale for freedom of expression based on an analogy to the economic concept of a free market. It holds that the truth will emerge from the competition of ideas in free, transparent public discourse, and that ideas and ideologies will be distinguished according to their superiority or inferiority and widespread acceptance among the population. The concept began to emerge in the courts in Abrams v. United States (1919) [very shortly after Schenck (1919)]. While the majority upheld the conviction of Jacob Abrams and five other men for distributing pamphlets critical of American intervention in Russia after the Bolshevik revolution, Justices Oliver Wendell Holmes and Louis Brandeis both dissented from the court majority, marking the emergence of a court minority committed to a broader defense of free speech. In the ensuing years, Holmes would write, "The only meaning of free speech" was that advocates of every set of beliefs, even "proletarian dictatorship," should have the right to convert the public to their views in the great "marketplace of ideas."

The Culture Wars

A concept that refers, in the United States, to the conflict between traditional or conservative values and progressive or liberal values. The expression entered U.S. political discourse during the 1990s to refer to the increasing polarization brought about by issues of abortion, gun laws, global warming, immigration, separation of church and state, privacy, recreational drug use, homosexuality, and censorship. But historians also use the term to describe the era of the 1920s when debates around fundamentalist religion, the teaching of evolution, immigration, eugenics, the KKK, the Harlem Renaissance, pluralism, prohibition, flappers, and gender roles powerfully divided Americans, often along urban and rural lines.

"Modernists"

A term used in the 1920s to describe the growing members of Protestant faiths who sought to integrate science (including the theory of evolution) and religion and adapt Christianity of the new secular culture. They were often in tension with "fundamentalists."

"Fundamentalists"

A term used in the 1920s to describe those who believed that the literal truth of the Bible formed the basis of Christian belief. They often felt threatened by the decline of traditional values and the increased visibility of Catholicism and Judaism because of immigration, and they launched a campaign to rid Protestant denominations of modernism and to combat the new individual freedoms that seemed to contradict traditional morality.

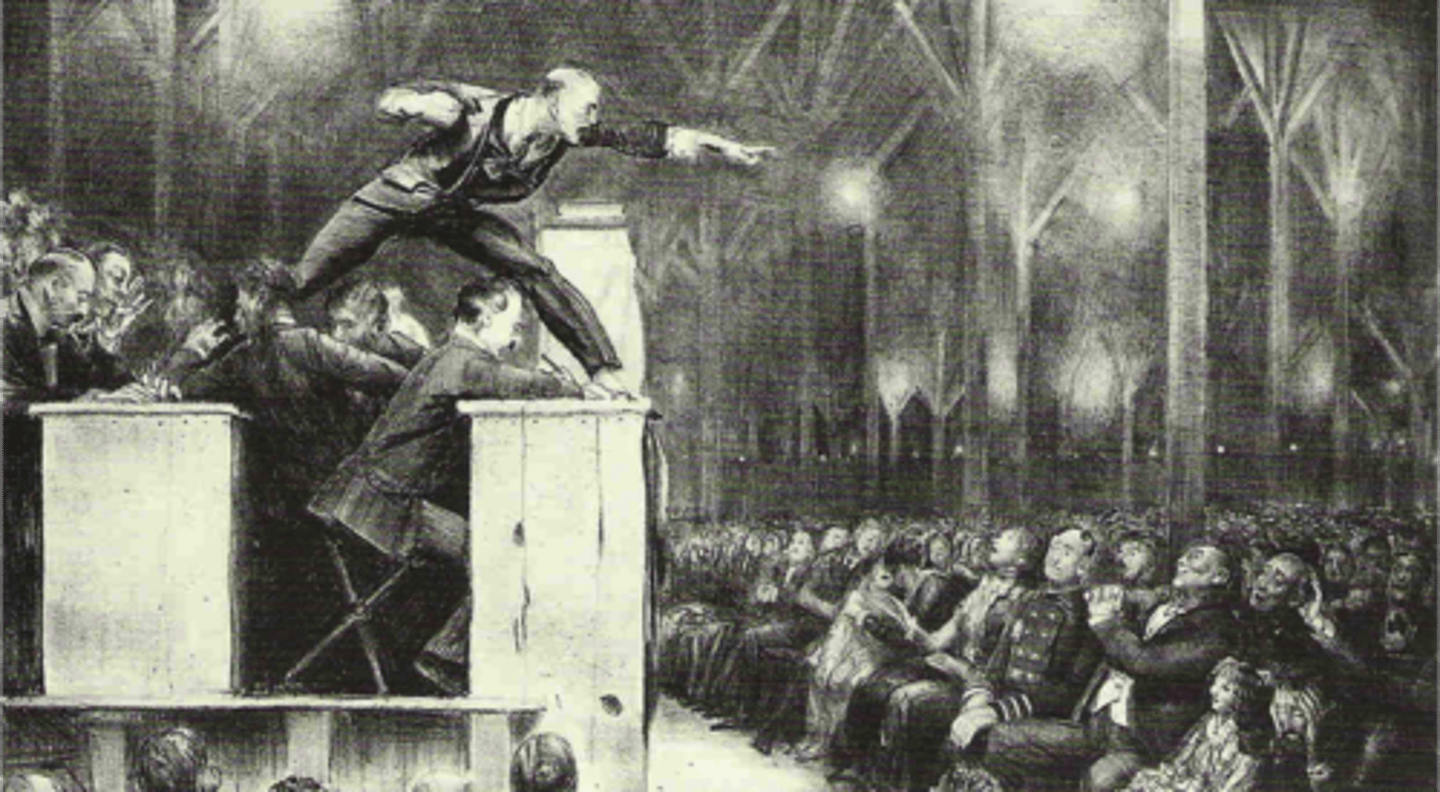

Billy Sunday

The leading--and perhaps the most flamboyant--fundamentalist of the 1920s. A talented professional baseball player who became a revivalist preacher, he drew huge crowds with a highly theatrical preaching style and a message denouncing sins ranging from Darwinism to alcohol. He was said to have preached to 100 million people during his lifetime, more than any other individual at that point in history.

Prohibition

A term that refers to the nationwide constitutional ban on the production, importation, transportation, and sale (but not consumption!) of alcoholic beverages that remained in place from 1920 to 1933 in the U.S.. During the 19th century, alcoholism, family violence, and saloon-based political corruption prompted activists, led by Protestant reformers, to end the alcoholic beverage trade to cure the ills of society. Prohibition become a hotly debated issue. Supporters, who were called "drys," presented it as a victory of public morals and health. But opponents, who were called "wets," presented it as a violation of individual liberty that led to large profits for the owners of illegal "speakeasies" (an illegal liquor store or nightclub) and the "bootleggers" (smugglers of illegal alcoholic beverages) who supplied them. Prohibition produced widespread corruption as police and public officials accepted bribes to turn a blind eye to violations of the law. Prohibition raised major questions of local rights, individual freedom, and the wisdom of attempting to impose religious and moral values on the entire society through legislation.

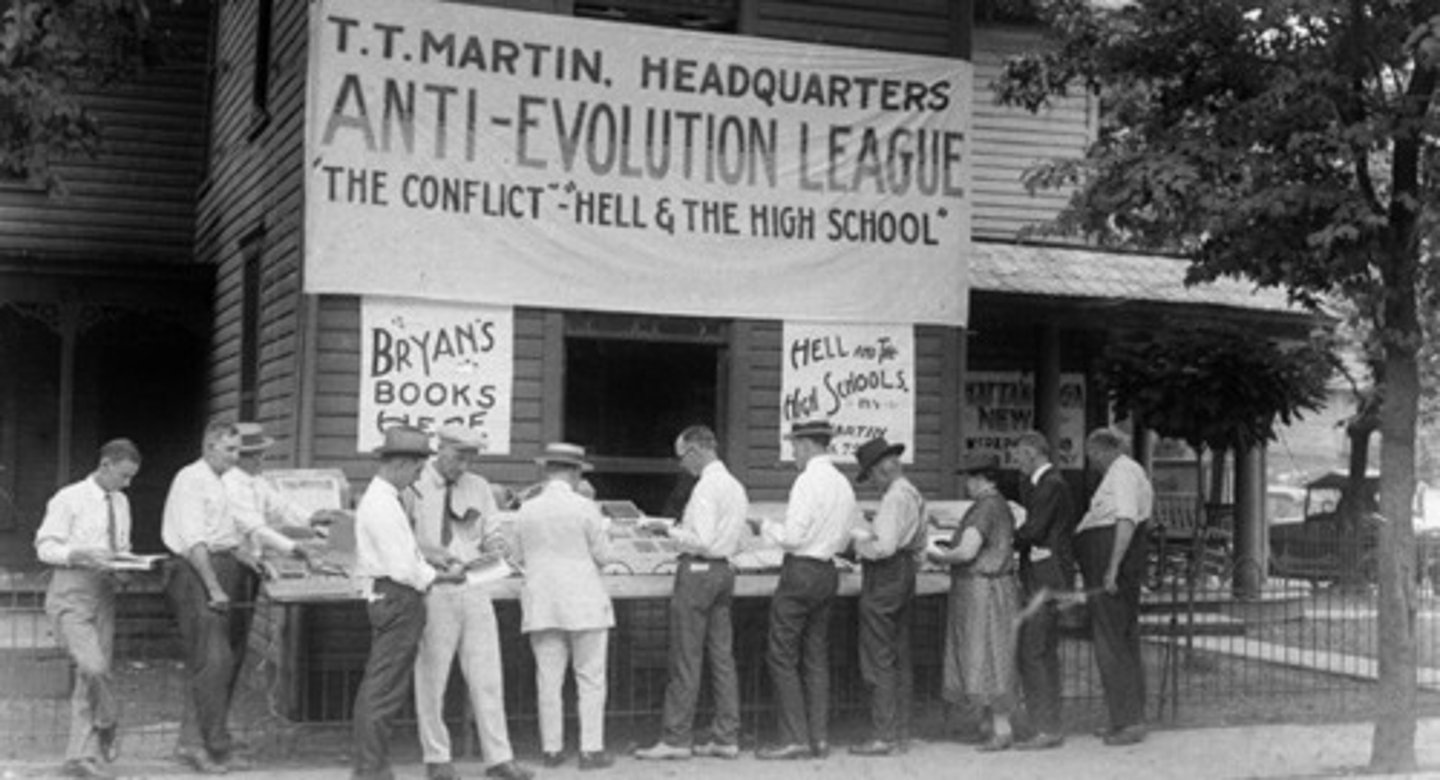

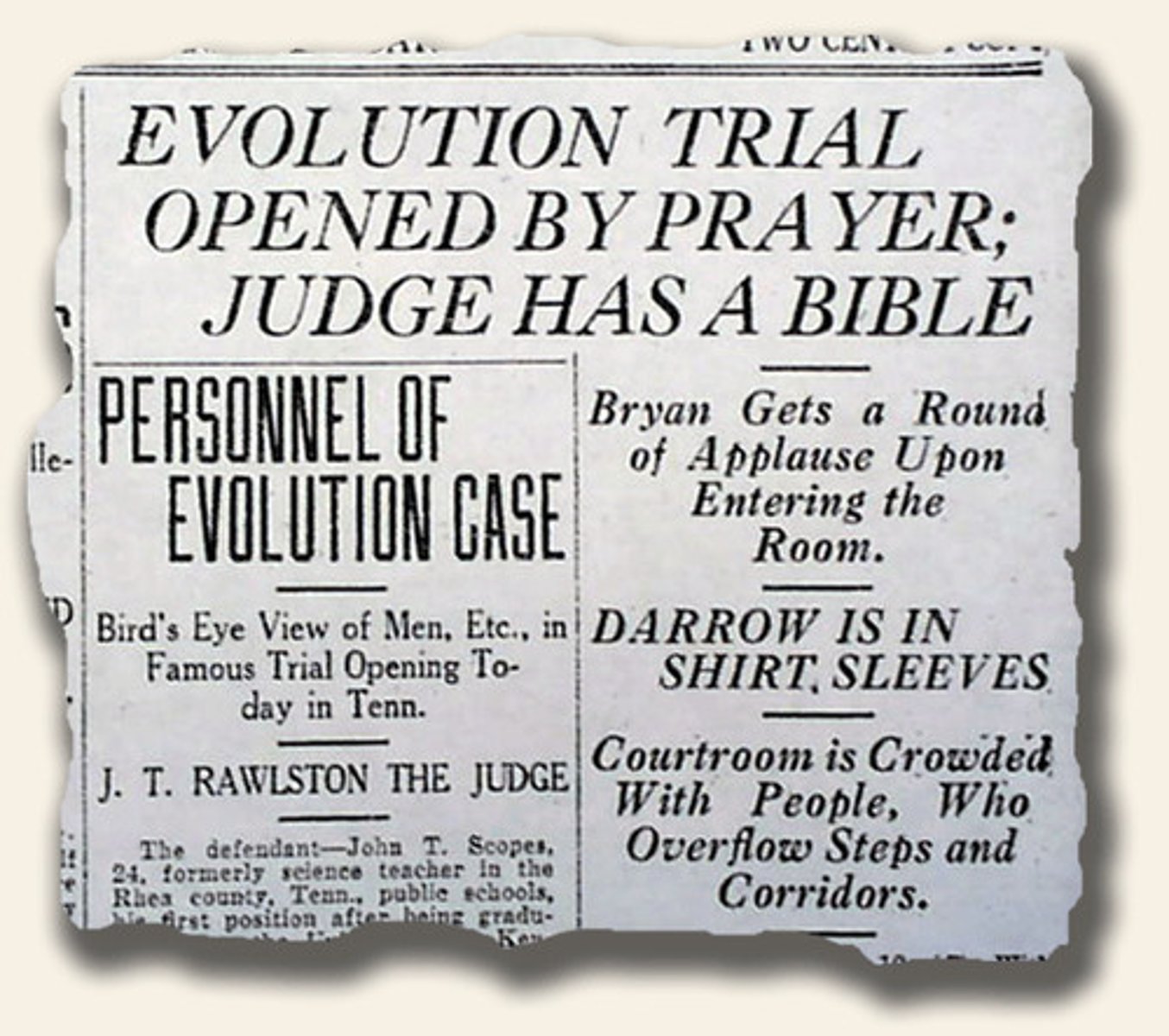

The Scopes (Monkey) Trial of 1925

A 1925 trial in Tennessee that threw into sharp relief the division between traditional values and modern, secular culture. A teacher in a TN public school was arrested for violating a state law that prohibited the teaching of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution. His trial became a national sensation, and the proceedings were carried live on national radio. The case reflected the enduring tension between two American definitions of freedom: moral liberty, or the voluntary adherence to time-honored religious beliefs, vs. the right to independent thought and individual self-expression. While the teachers was found guilty, the trial weakened the movement for religious fundamentalism.

The Second Klan

The resurgence of the KKK (Ku Klux Klan) during the 1920s among white, native-born, Protestants. Unlike the KKK of the Reconstruction, the organization was popular and visible in the North and the West, as well as its traditional home in the South. Moreover, it attacked a broader array of targets than just African Americans: immigrants (especially Jews and Catholics) and all the forces (feminism, unions, immorality, sometimes even giant corporations) that endangered "individual liberty."

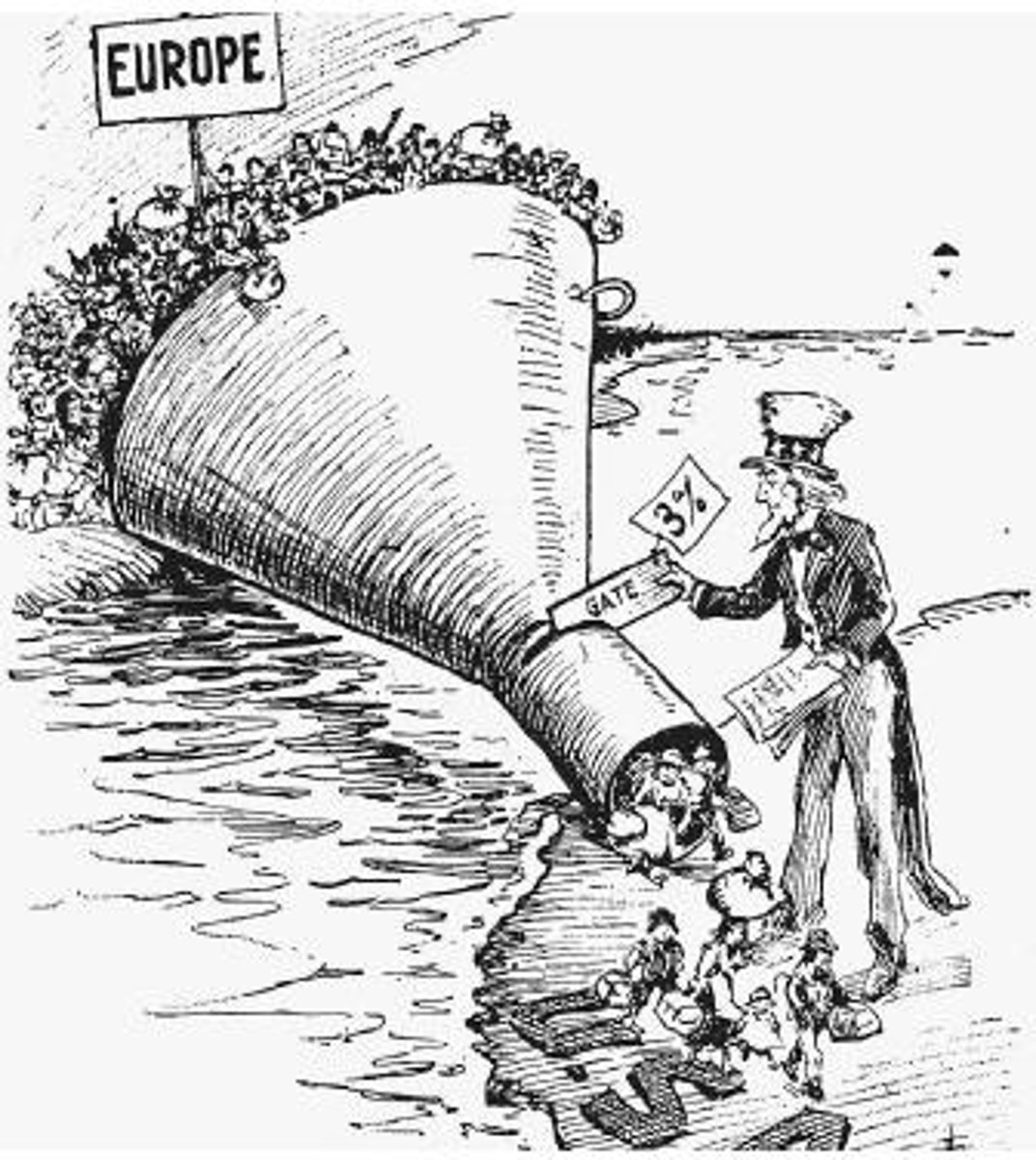

The National Origins Act of 1924

Reflecting a fundamental change in immigration policy, this law permanently limited European immigration to 150,000 per year, distributed according to as series of national quotas that severely restricted the numbers from Southern and Eastern Europe. The law aimed to ensure that descendants of the old immigrants (from Northern and Western Europe) forever outnumbered the children of the new (from Southern and Eastern Europe). It also barred all immigrants who were ineligible for naturalized citizenship (that is, the entire population of Asia, which had been declared ineligible for citizenship ever since the 1790 Naturalization Act). However, the law placed no limits on immigration from the Western hemisphere.

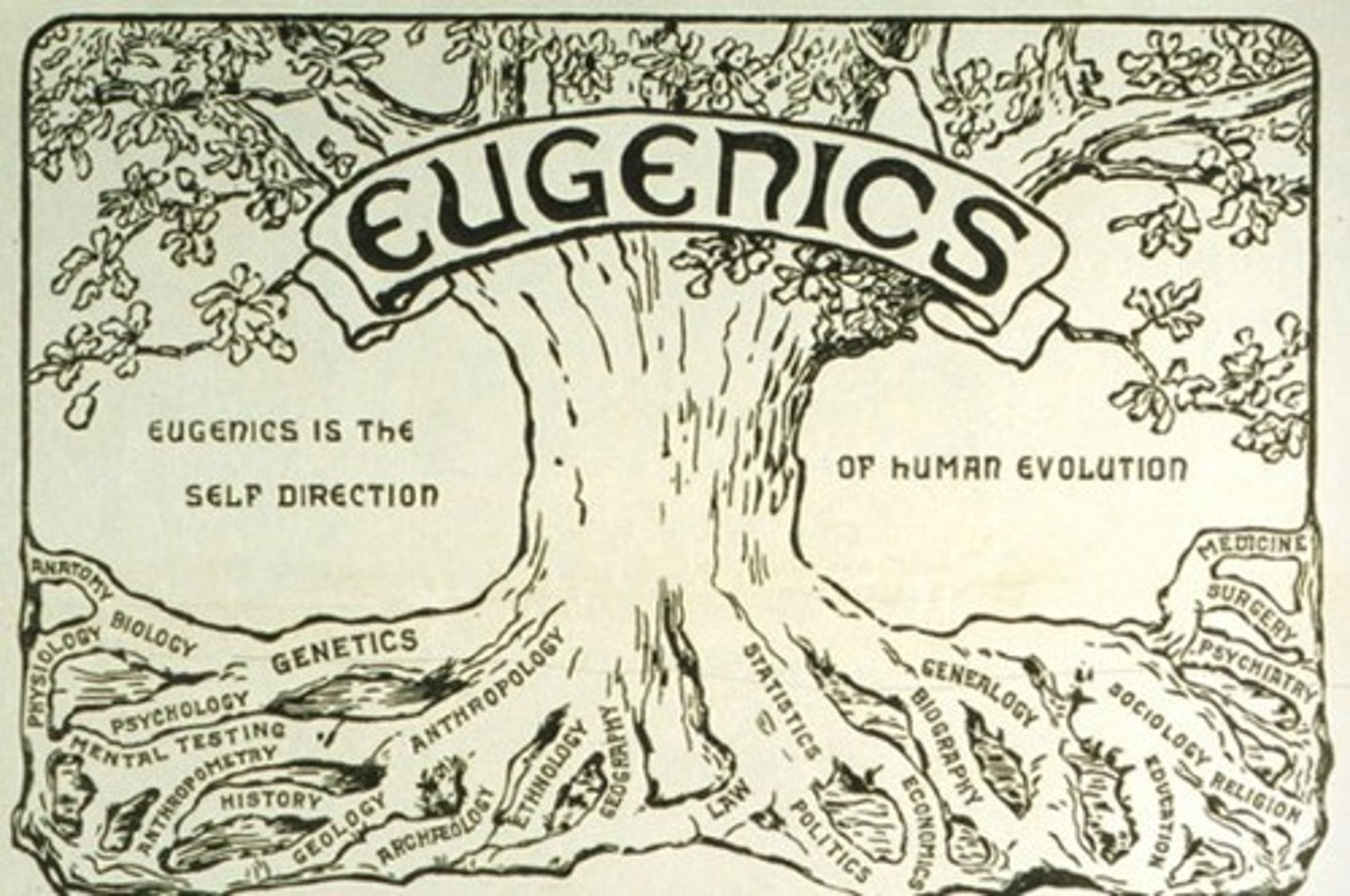

Buck v. Bell, 1927

In this case, the Supreme Court upheld the Constitutionality of forced sterilization laws such as the 1907 Indiana law authorizing doctors to sterilize insane and "feeble-minded" inmates in mental institutions so that they would not pass on their "defective" genes to children. The decision was largely seen as an endorsement of eugenics—the attempt to improve the human race by eliminating "defectives" from the gene pool.

The Harlem Renaissance

A flourishing of African American cultural, social, and artistic expression throughout the 1920s centered in the northernmost borough of New York City, which had gained an international reputation as the capital of black America following the Great Migration as tens of thousands of Africans Americans settled there during the WWI era. Including writers like Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes, and Claude McKay, this, this artistic flourishing was associated with the "New Negro" and efforts to challenge the cultural of white supremacy.

The "New Negro"

A term associated both with the politics of pan-Africanism and the militancy of Marcus Garvey's movement of the 1920, and also associated in art with the Harlem Renaissance artists who rejected established stereotypes and sought to replace them with black values instead.

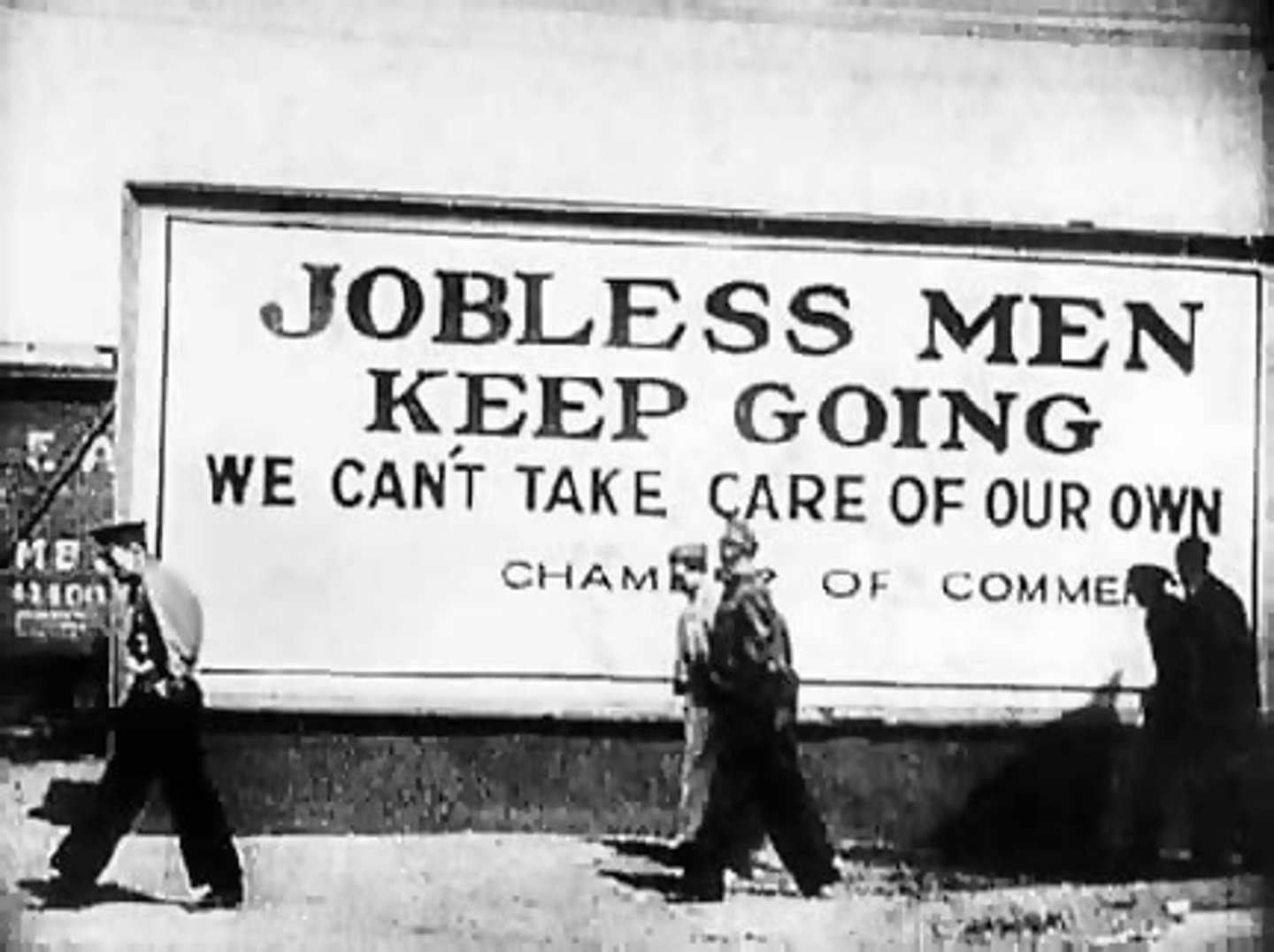

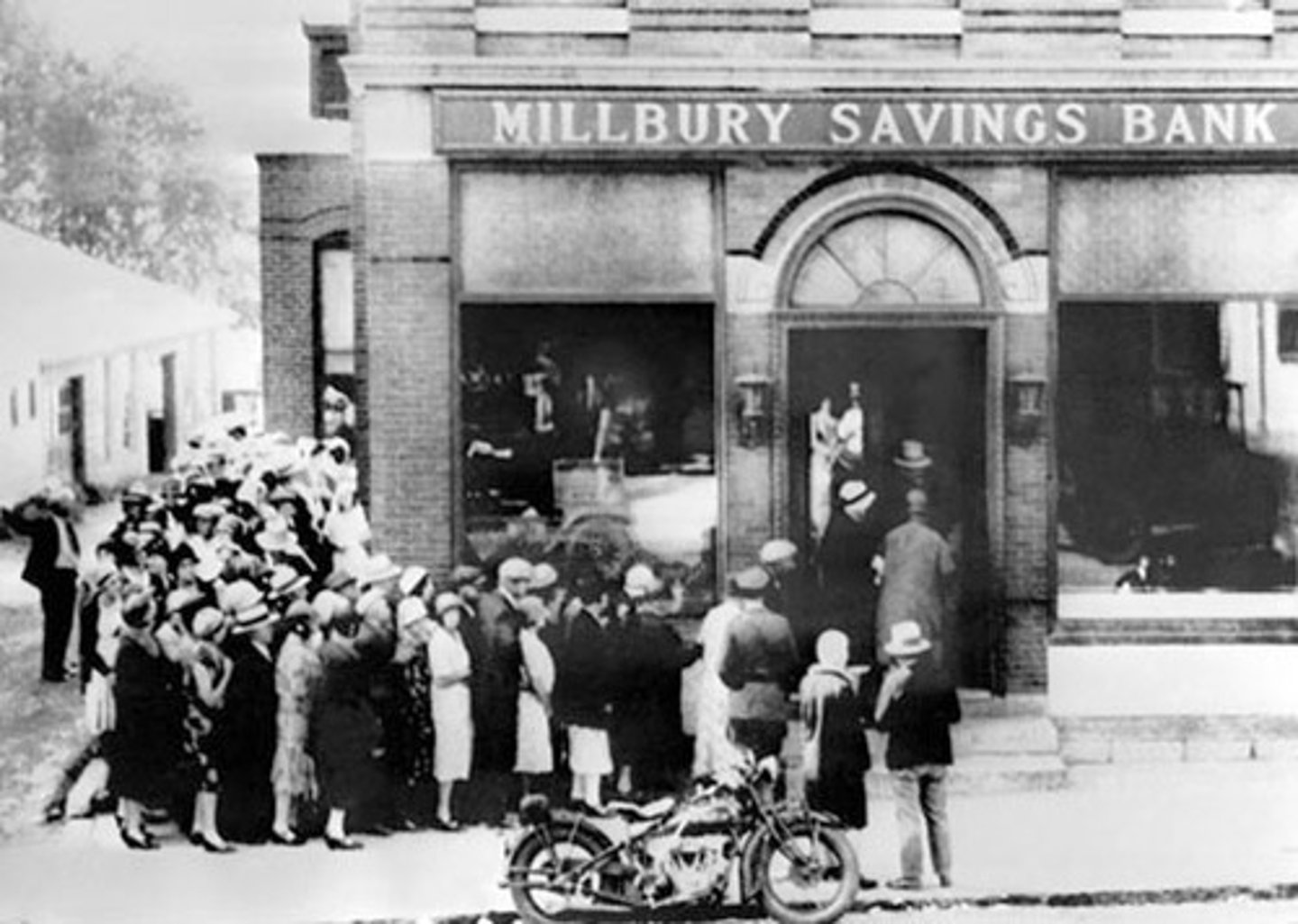

The Great Depression

Lasting in the U.S. from 1929 to 1939, this was the deepest, longest, and most widespread economic downturn in the history of the industrialized world. It began after the stock market crash of October 1929, which sent Wall Street into a panic and wiped out millions of investors. Over the next several years, personal income, consumer spending, investment, and government tax revenue all dropped causing steep declines in industrial output, international trade, and employment as failing companies laid off workers. By 1932, when this had reached its lowest point, some 11 million Americans--about 25% of the U.S. labor force--were unemployed and nearly half the country's banks had failed.

Herbert Hoover's response to the Great Depression

In the eyes of many American's, this President's response to the Great Depression seem inadequate and uncaring, leading people to call the shantytowns of homeless people springing up outside of many cities "Hoovervilles." To be fair, the federal government had never faced an economic crisis as severe as the Great Depression. At first, Hoover was committed to "associational action;" he put his faith in voluntary steps by business to maintain investment and employment and efforts by local charity organizations to assist needy neighbors. By 1932, Hoover had to admit that voluntary action had failed to stem the Depression, and he accepted greater federal government engagement, signing laws creating the Reconstruction Finance Corporation and the Federal Home Loan Bank System.

The Bonus Army

In the spring of 1932, 20,000 unemployed WWI veterans descended on Washington to demand early payment of a bonus due in 1945. However, they were driven away by federal soldiers led by the army's chief of staff, Douglas MacArthur, and their treatment seemed to confirm in the public mind Hoover's lack of sympathy for unemployed Americans.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR)

President of the U.S. from 1932-1945, serving through the Great Depression and World War Two.

Raised in privilege in a New York country estate, he came to be beloved as the symbolic representation of ordinary citizens. A Democrat, who was elected to a record four terms, he was the dominant leader of the Democratic Party, assembled the "New Deal Coalition," and redefined "liberalism" for much of the 20th century. Very few Americans realized that the president who projected an image of vigorous leadership during the 1930s and WWII was confined to a wheelchair, paralyzed from the waist down from polio. Scholars consider him to be among the greatest presidents in U.S. history.

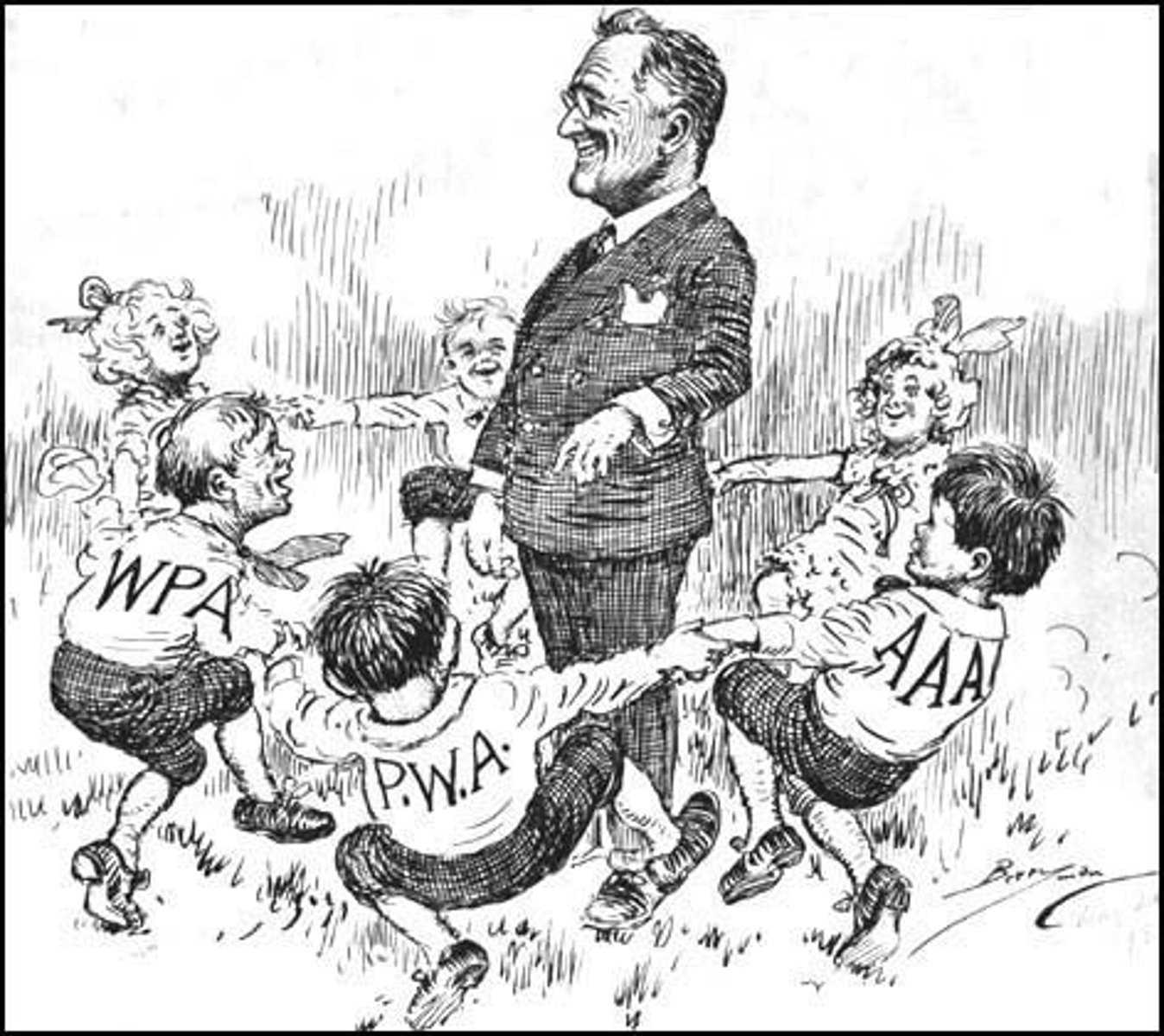

The New Deal

This term, originating in an FDR speech, came to refer to the entire collection of federal programs that FDR initiated in response to the Great Depression. Consisting of a wide variety of very diverse programs and initiatives, many of them known by the acronyms (WPA, CCC, TVA, AAA) (aka "alphabet soup"), they generally involved a more active role for the government in the economy. Historians have often summed up the New Deal as an effort to provide "relief, recovery, and reform" (the "Three Rs").

The New Deal Coalition

During the 1930s, FDR assembled this broad group of constituencies to support the Democratic Party. It included groups like farmers, industrial workers, the reform-minded urban middle class, liberal intellectuals, northern African-Americans, and, somewhat incongruously, the white supremacist South, united by the belief that the federal government must provide Americans with protection against the dislocations caused by modern capitalism. This coalition held together, for the most part, and enabled the Democratic Party to dominate U.S. politics until the late 1960s.

"Liberalism"

This term was given new meaning by FDR and the New Deal. Traditionally understood as limited government and free market economics, in the 1930s it took on its modern meaning of active efforts by the national government to modernize and regulate the market economy and to uplift less fortunate members of society.

The First Hundred Days

The first, roughly, three months of FDR's first term in office, during which time fifteen major pieces of legislation were enacted (most of which attempted some form of economic recovery from the Great Depression), making it one of the most productive periods in the history of the U.S. Congress.

The NIRA (National Industrial Recovery Act)

A piece of New Deal recovery legislation during the First Hundred Days, this act established the National Recovery Administration, which would work with groups of business leaders to establish industry codes that set standards for output, prices, and working conditions. Thus, "cutthroat" competition (in which companies took loses to drive competitors out of business) would be ended. Section 7a of the act recognized workers' right to organize unions. Very controversial, in part because large companies dominated the code-writing process to protect their own interests against smaller competitors, the act produced neither economic recovery nor peace between employers and workers. It did, however, undercut the pervasive sense that the federal government was doing nothing to deal with the economic crisis. It ended in 1935 when the Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional, in part, because its codes and other regulations attempted to regulate local business that did not engage in interstate commerce.

The CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps)

A piece of New Deal relief legislation during the First Hundred Days, this program set unemployed unmarried young men (the kinds of people who might traditionally be drawn by despair into radical or revolutionary political movements) to work on public works projects like forest preservation, flood control, and the improvement of national parks and wildlife preserves. By the time the program ended in 1942, over three million men had worked in the camps, where they received monthly checks of $30 ($25 of which had to be sent home to their parents, helping them to also stay afloat during the Depression).

The TVA (Tenesse Valley Authority)

A piece of New Deal legislation during the First Hundred Days that served as both relief and recovery by initiating government-planned economic transformation as much as economic relief. This law put thousands of people to work in the construction of a series of dams to prevent floods and deforestation along the Tennessee River and to provide cheap electric power for homes and factories in a seven-state region of the South where many families still lived in isolated log cabins. This law put the federal government, for the first time, in the business of selling electricity in competition with private companies.

The AAA (Agricultural Adjustment Act)

A piece of New Deal recovery legislation during the First Hundred Days, this law authorized the federal government to try to raise farm prices by setting production quotas for major crops and paying farmers to plant less. It succeeded in raising farm prices and incomes, but not all farmers benefited (particularly poor tenants and sharecroppers who worked on land owned by others). It ended in 1936 when the Supreme Court ruled it to be unconstitutional exercise of congressional power over local economic activities.

The Dust Bowl

The area centered around Oklahoma, and including parts of Texas, Kansas, and Colorado, during the 1930s where, for several years, major dust storms occurred. The dust storms, which displaced more than a million farmers (many who migrated West in search of jobs were derogatorily called "Okies"), were caused by severe drought and mechanized agriculture (with deep plowing) that had pulverized the topsoil and killed the native grasses that prevented erosion.

The SEC (the Securities and Exchange Commission)

A piece of New Deal reform legislation that regulated the stock and bond markets.Prior to the its creation, oversight of the trade in stocks, bonds, and other securities was virtually nonexistent, which led to widespread fraud, insider trading and other abuses.

The Glass-Steagall Act

This New Deal law reformed the banking industry by barring commercial banks from becoming involved in the buying and selling of stocks. Until its repeal in the 1990s, the law lent stabilty, security, and confidnece in the commercial banking system by preventing many of the irresponsible practices that had contributed to the stock market crash.

FDIC (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation)

This New Deal law reformed the banking industry by establishing a government system that insured the accounts of individual depositors in banks, thus increasing the security, stability, and confidence in the nations banking system.

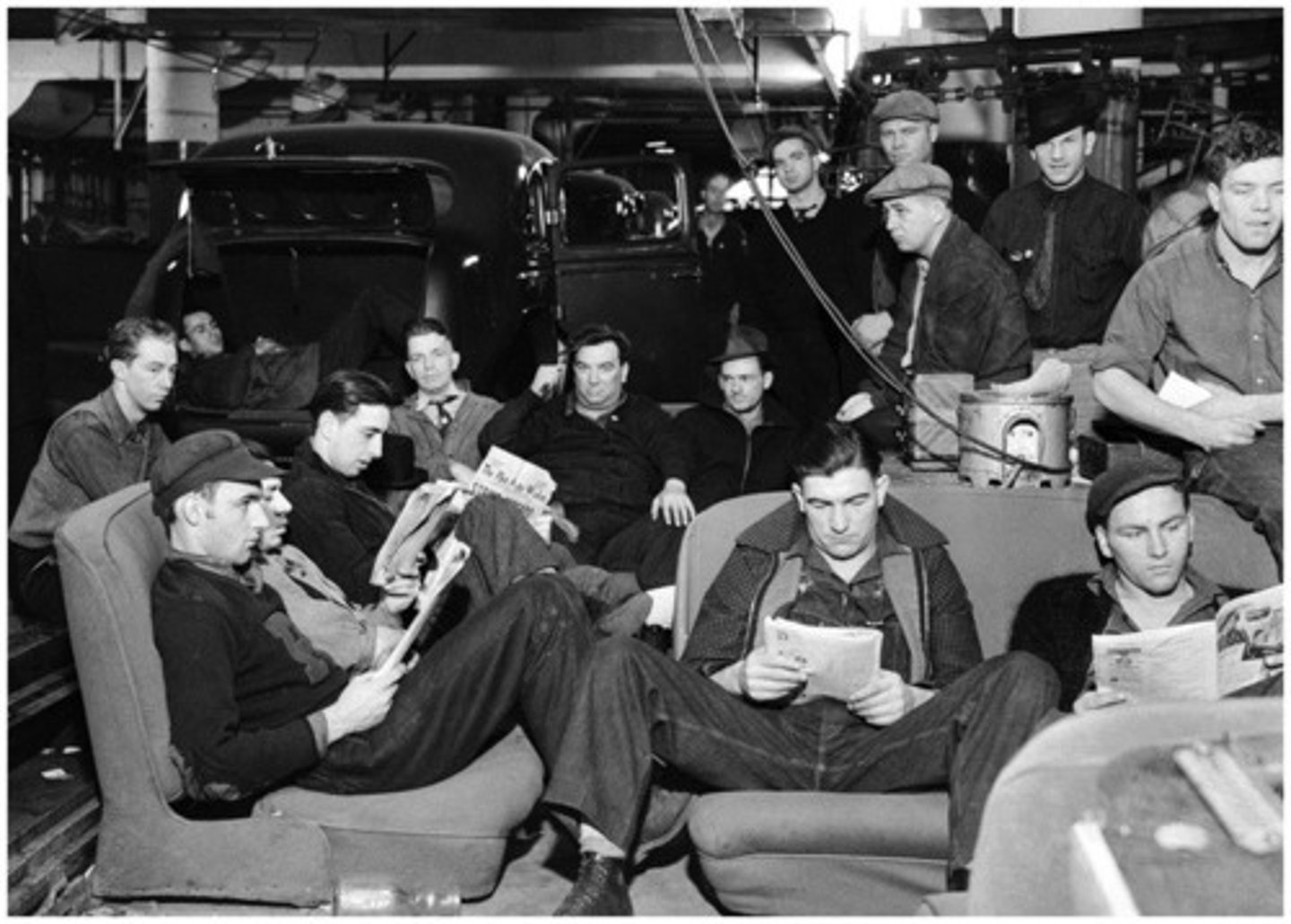

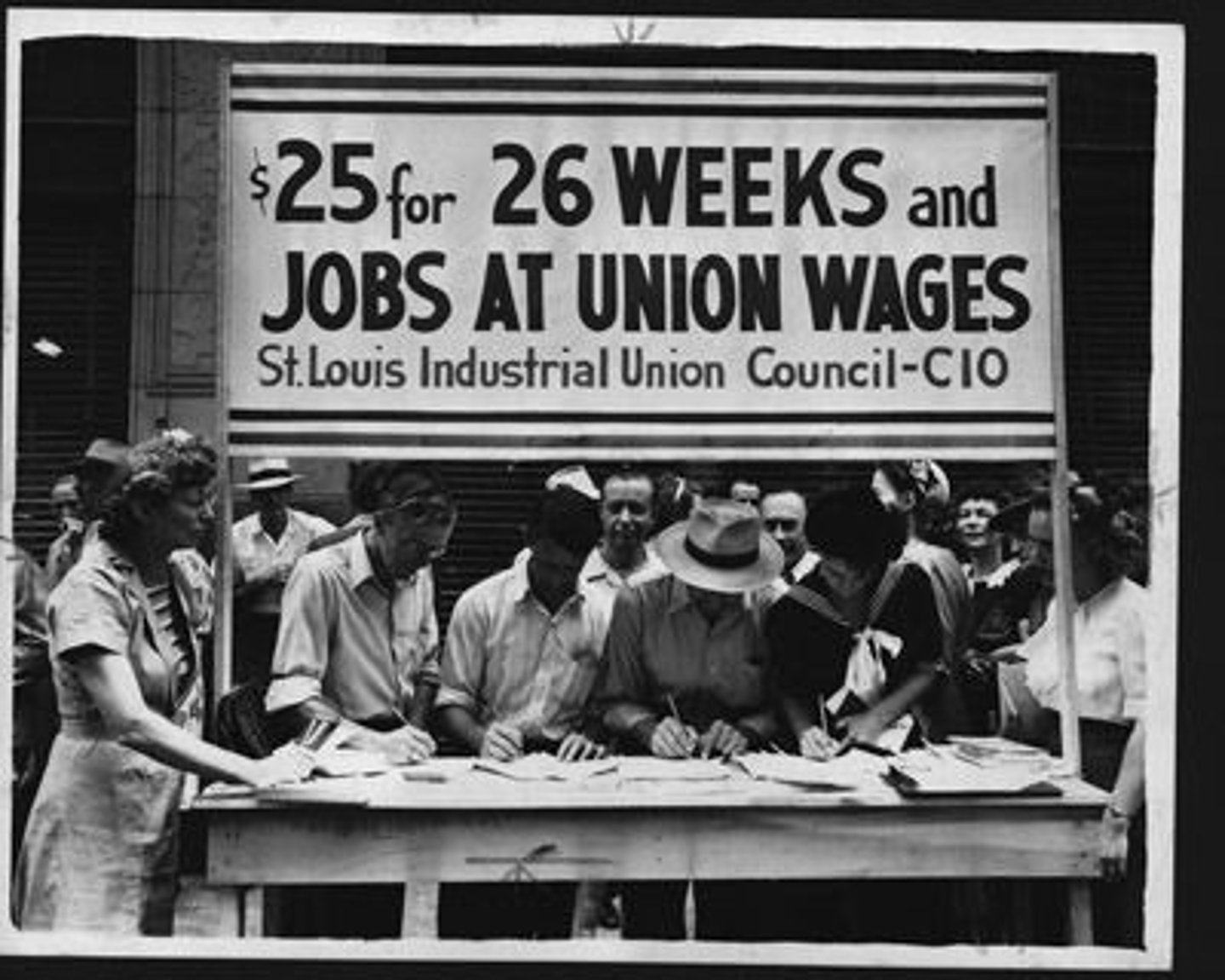

"Labor's Great Upheaval"

This term refers to the upsurge in activity, unprecedented militancy, and increased membership of organized labor during the 1930s. The era witnessed the creation of the CIO (The Congress of Industrial Organizations, which is a union, not a New Deal program) that aimed to organize unions that welcomed all the workers in a particular industry (as opposed to just a skilled set of workers in a particular craft). The United Auto Workers, used "sit-down strikes (a strikingly effective tactic), and along with thousands of other strikes, the era saw the doubling of the number of Americans who were members of unions (9 million by 1940). After nearly a century of struggle, American workers finally won the right to form unions, and thus to bargain collectively to secure for themselves a larger share of the profits of American capitalism. Unlike in the past, the federal government seemed to be on labor's side; first the NIRA and then the Wagner Act granted workers the right to form unions.

Huey Long

The populist and dictatorial Louisiana governor, and afterwards Senator, referred to as "the Kingfish," who became of the most colorful characters in American politics. A critic of FDR's New Deal programs from the left, in 1934, he launched the "Share Our Wealth" movement, with the slogan "Every Man a King." He called for the confiscation of most of the wealth of the richest Americans in order to finance an immediate grant of $5,000 and a guaranteed job and annual income for all citizens. He was on the verge of announcing a run for president when the son of a defeated political rival assassinated him in 1935.

The Second New Deal

Launched in 1935 during the second half of FDR's first term--after the Supreme Court has begun striking down elements of the First New Deal which were passed during the First Hundred Days--this second wave of New Deal legislation focused on achieving economic security--or the guarantee that Americans would be protected against unemployment and poverty. It included the Social Security Act, the Rural Electrification Agency, and the Wagner Act. And it transformed the relationship between the federal government and American citizens; before the 1930s, national political debate often revolved around the question of whether the federal government should intervene in the economy. After the New Deal, debate rested on how it should intervene.

The WPA (Works Progress Administration)

A popular Second New Deal relief program, this one hired about three million people during each year of its existence and put them to work constructing thousands of public buildings and bridges, more than 500,000 miles of roads, and 600 airports. It built stadiums, swimming pools, and sewage treatment plants. The most famous projects were in the arts, in which hundreds of artists worked to decorate public buildings with murals, and many other writers, actors, musicians, dancers, and photographers produced work for the public.

The Wagner Act

A major piece of reform legislation of the Second New Deal, this act was know at the time as "Labor's Magna Carta" because it brought democracy into the workplace by empowering the National Labor Relations Board to supervise elections in which employees voted on union representation (thus, effectively, ensuring workers' right to form unions). (Section 7a of the NIRA had previously established workers' right to form unions, but the Supreme Court had struck down the NIRA in 1935.) This act also outlawed "Unfair labor practices," including the firing and blacklisting of union organizers.

The Social Security Act

The centerpiece of the Second New Deal, this program embodied FDR's conviction that the national government had a responsibility to ensure the material well-being of ordinary Americans. It created a system of unemployment insurance, old age pensions, and aid to the disabled, the elderly poor, and families with dependent children. Reflecting a hybrid of national and local funding, control, and eligibility standards, its old age pensions were administered nationally but paid for by taxes on employers and employees. Such taxes also paid for payments to the unemployed, but this program was highly decentralized, with the states retaining considerable control over the level of benefits. By committing the government to supervising not simply temporary relief but a permanent system of social insurance, this program launched the American version of the welfare state.

The Welfare State

A term that originated in Britain during World War II to refer to a system of income assistance, health coverage, and social services for all citizens. It first began to take shape in the U.S. in 1930s with the creation of the Social Security program, and was later expanded in the 1960s with the addition of the Medicare and Medicaid programs, and reformed again in 2010 by the Affordable Care Act ("Obamacare"). The American version of the welfare state marked a radical departure from government policies prior to the 1930s, but compared with similar programs in Europe, it has always been far more decentralized, involved lower levels of public spending, and covered fewer citizens.

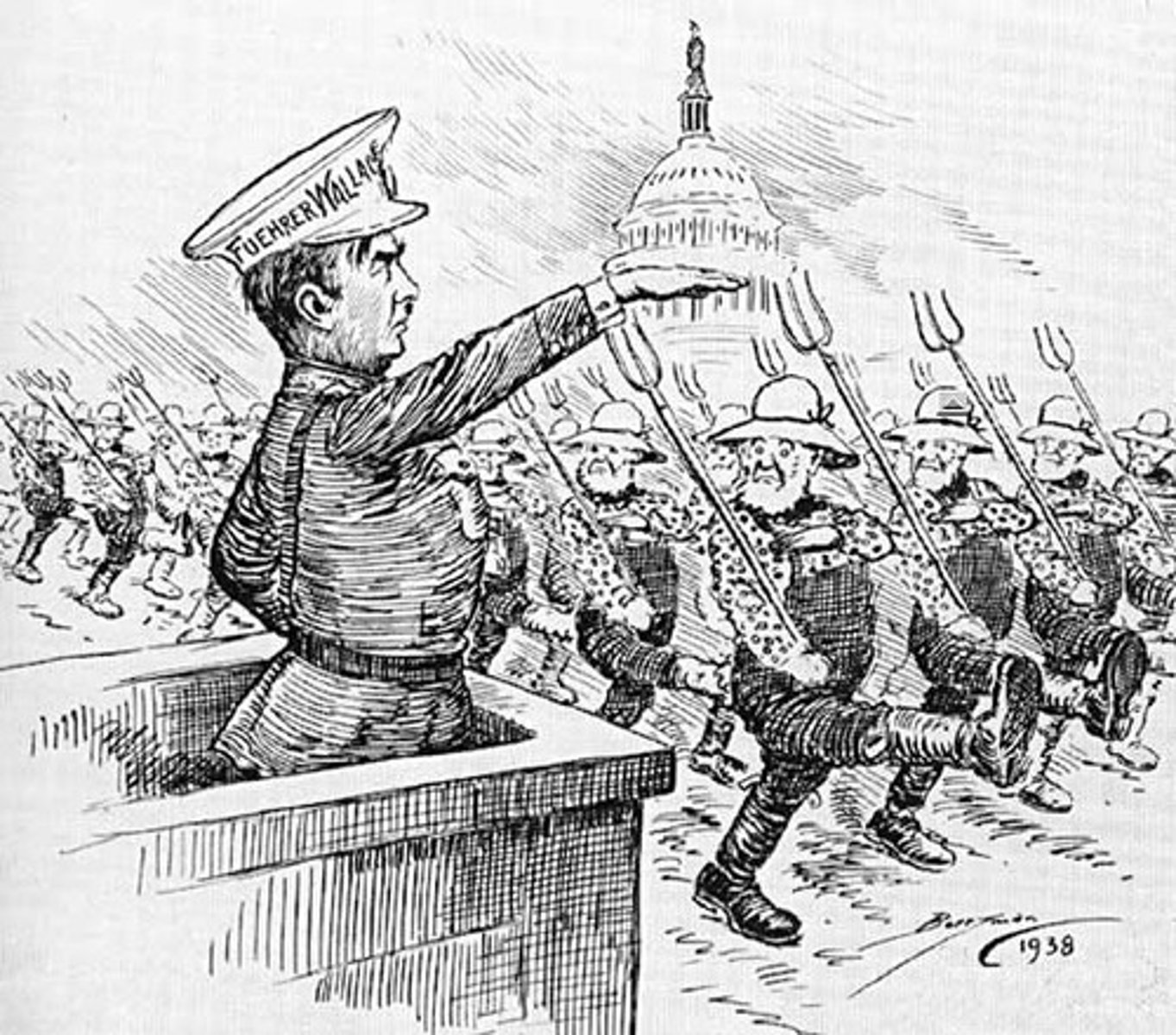

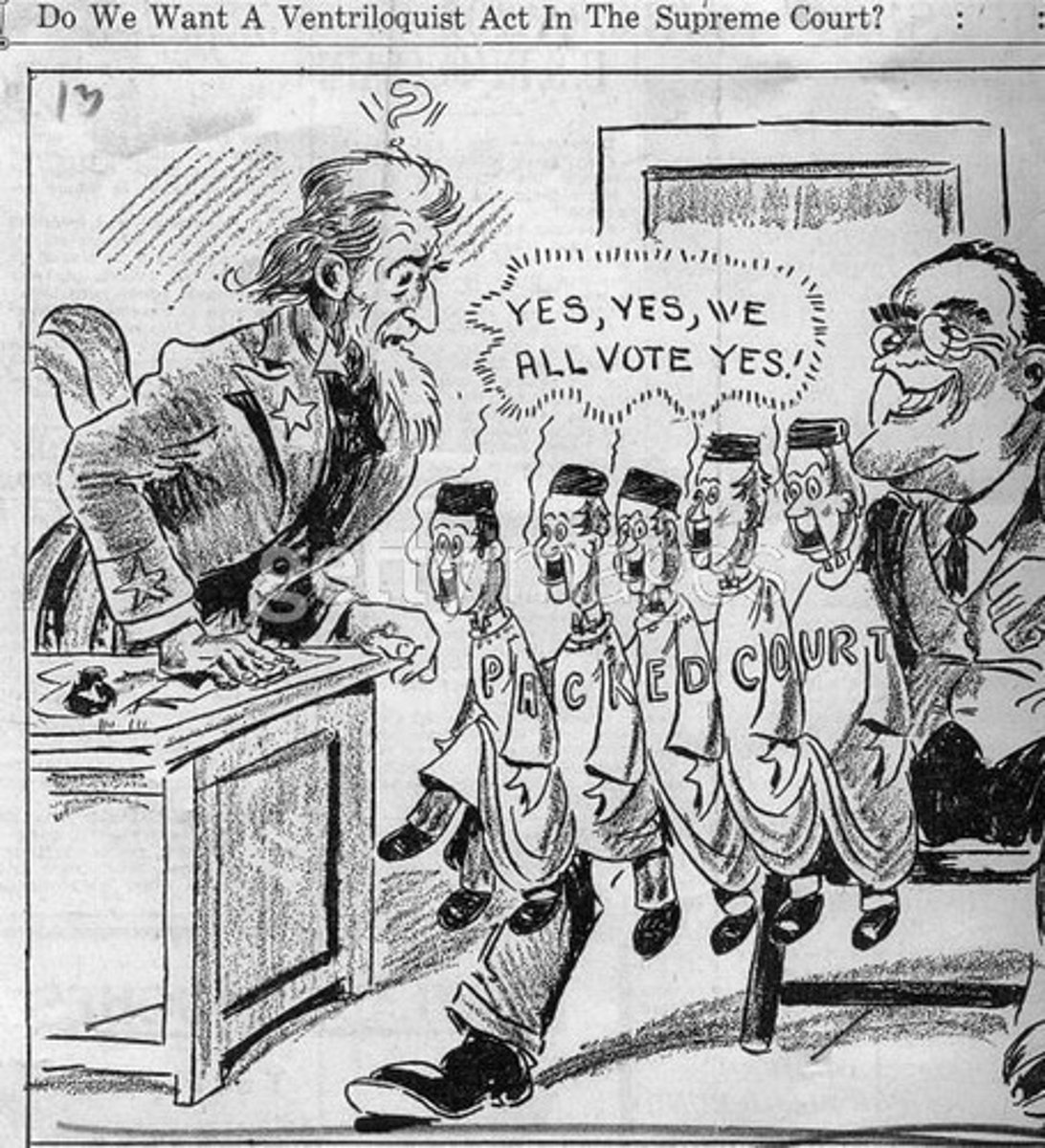

FDR's Court-Packing Scheme

Emboldened by his reelection in 1936, FDR proposed that the president be allowed to appoint a new Supreme Court justice for each one who remained on the Court past age seventy (an age that six of the nine had already surpassed). Publicly, FDR used the pretense that several members of the Court were too old to perform their functions, but his real aim was to change the balance of power on the Court that, he feared, might invalidate Social Security, the Wagner Act, and other measures of the Second New Deal. The plan aroused cries that the president was an aspiring dictator. Congress rejected it. But FDR accomplished his underlying purpose. The Supreme Court suddenly revealed a new willingness to support economic regulations by both the federal and state government (thus abandoning "Lochnerism"). The Court's willingness to accept the New Deal marked a permanent change in judicial policy; having declared dozens of economic laws unconstitutional in the decades leading up to 1937, the justices have rarely done so since.

The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)

A last major piece of (reform) legislation of the New Deal, it established the practice of the federal regulation of wages and working conditions, another radical departure from pre-Depression policies and "Lochnerism." When it passed in 1938, it banned goods produced by child labor from interstate commerce, set forty cents as the minimum hourly wage, and required overtime pay for hours of work exceeding forty per week (effectively creating "the weekend"!).

John Maynard Keynes

A British economist who wrote The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936) (widely known simply by the abbreviated title, The General Theory) and went on to become the founder of modern macroeconomics and one of the most influential economists of the 20th century. His ideas definedthe economic school of thought known as Keynesian economics. [Challenging Adam Smith's notion that the economy is a product of nature best left alone to regulate itself through natural laws of supply and demand (the "invisible hand"), Keynes said the economy is like a "machine" that governments must be fine-tuned from time to time;]

During the Great Depression, he challenged economists' traditional belief in the sanctity of balanced budgets. Large-scale government spending, he insisted, was necessary to sustain purchasing power and stimulate economic activity during downturns. Such spending should be enacted even at the cost of a budge deficit (a situation in which the government spends more money that it takes in). FDR was persuaded, and Keynesian economic assumptions were adopted by most American politicians until the Conservative Resurgence of the 1970s and 80s.

![<p>A British economist who wrote The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936) (widely known simply by the abbreviated title, The General Theory) and went on to become the founder of modern macroeconomics and one of the most influential economists of the 20th century. His ideas definedthe economic school of thought known as Keynesian economics. [Challenging Adam Smith's notion that the economy is a product of nature best left alone to regulate itself through natural laws of supply and demand (the "invisible hand"), Keynes said the economy is like a "machine" that governments must be fine-tuned from time to time;]<br>During the Great Depression, he challenged economists' traditional belief in the sanctity of balanced budgets. Large-scale government spending, he insisted, was necessary to sustain purchasing power and stimulate economic activity during downturns. Such spending should be enacted even at the cost of a budge deficit (a situation in which the government spends more money that it takes in). FDR was persuaded, and Keynesian economic assumptions were adopted by most American politicians until the Conservative Resurgence of the 1970s and 80s.</p>](https://knowt-user-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/072c69f6-74d9-41ee-a558-e4d022b96c0d.image/jpeg)

Eleanor Roosevelt

FDRs wife (and distant cousin), she transformed the role of First Lady, turning a position with no formal responsibilities into a base for political action. She traveled widely, spoke out on public issues, wrote a regular newspaper column that sometimes disagreed openly with her husband's policies, and worked to enlarge the scope of the New Deal in areas like civil rights, labor legislation, and work relief. Historians consider her one of the more influential champions of human rights in the 20th century for her leadership in the creation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights ("UDHR") after World War Two.

The Southern Veto

A reference to the power of the white South to mold the New Deal into an entitlement for white Americans and to deny many of the New Deal's benefits to African Americans. A Democrat himself, FDR understood he needed the votes of Southern Democrats in order to pass his New Deal Legislation. And Southern Democrats were tremendously powerful in Congress where they held many key leadership positions and committee chairmanships. Therefore, FDR had to accommodate the Southern Democrats' desire to insert racially discriminatory language in many New Deal bills in order to get them enacted into law. For example, at their insistence, both the Social Security Act and the FLSA excluded agricultural and domestic workers (the largest category of black employment).

John Collier and the Indian New Deal

The Commissioner of Indian Affairs during the 1930s who oversaw the most radical shift in federal Indian policy in U.S. history. He ended the policy of forced assimilation and allowed Indians unprecedented cultural autonomy. He replaced the boarding schools meant to eradicate the tribal heritage of Indian children with schools on reservations, dramatically increased spending on Indian health, and secured passage of the Indian Reorganization Act.

The Indian Reorganization Act, 1934

A New Deal era law that ended the policy, dating back to the Dawes Act of 1887, of dividing Indian lands into small plots for individual Indian families and selling off the rest to white settlers. Federal authorities once again recognized Indians' right to govern their own affairs, except where specifically limited by national laws.

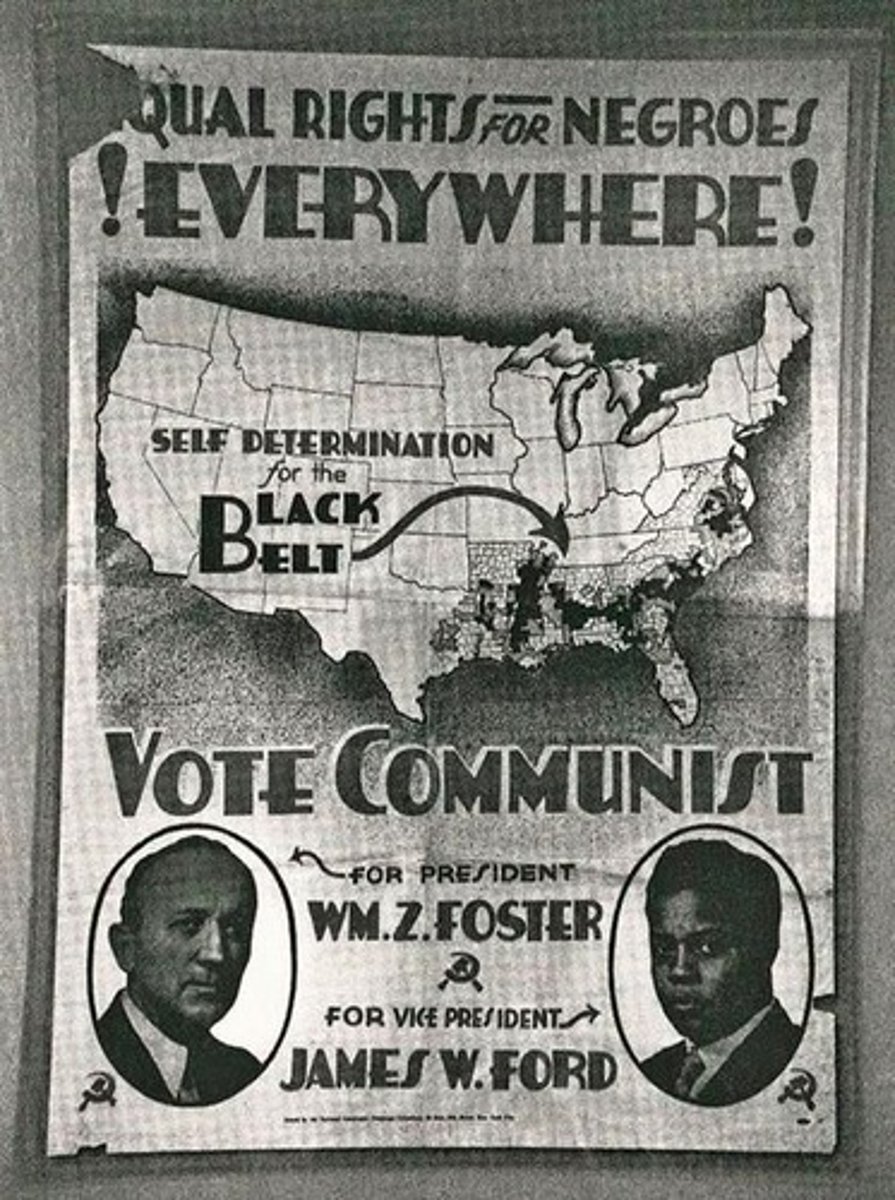

The Popular Front

A period during the 1930s when the Communist Party gained unprecedented respectability in the U.S. by seeking to ally itself with socialists and New Dealers in movements for social change, urging reform of the capitalist system rather than revolution. During this period the Communist Party's vitality--its involvement in a mind-boggling array of activities, including demonstrations for the unemployed, struggles for industrial unionism, and a renewed movement for civil rights--made it the center of gravity for a broad democratic upsurge, and it helped to imbue New Deal liberalism with a militant spirit and a more pluralistic understanding of Americanism.

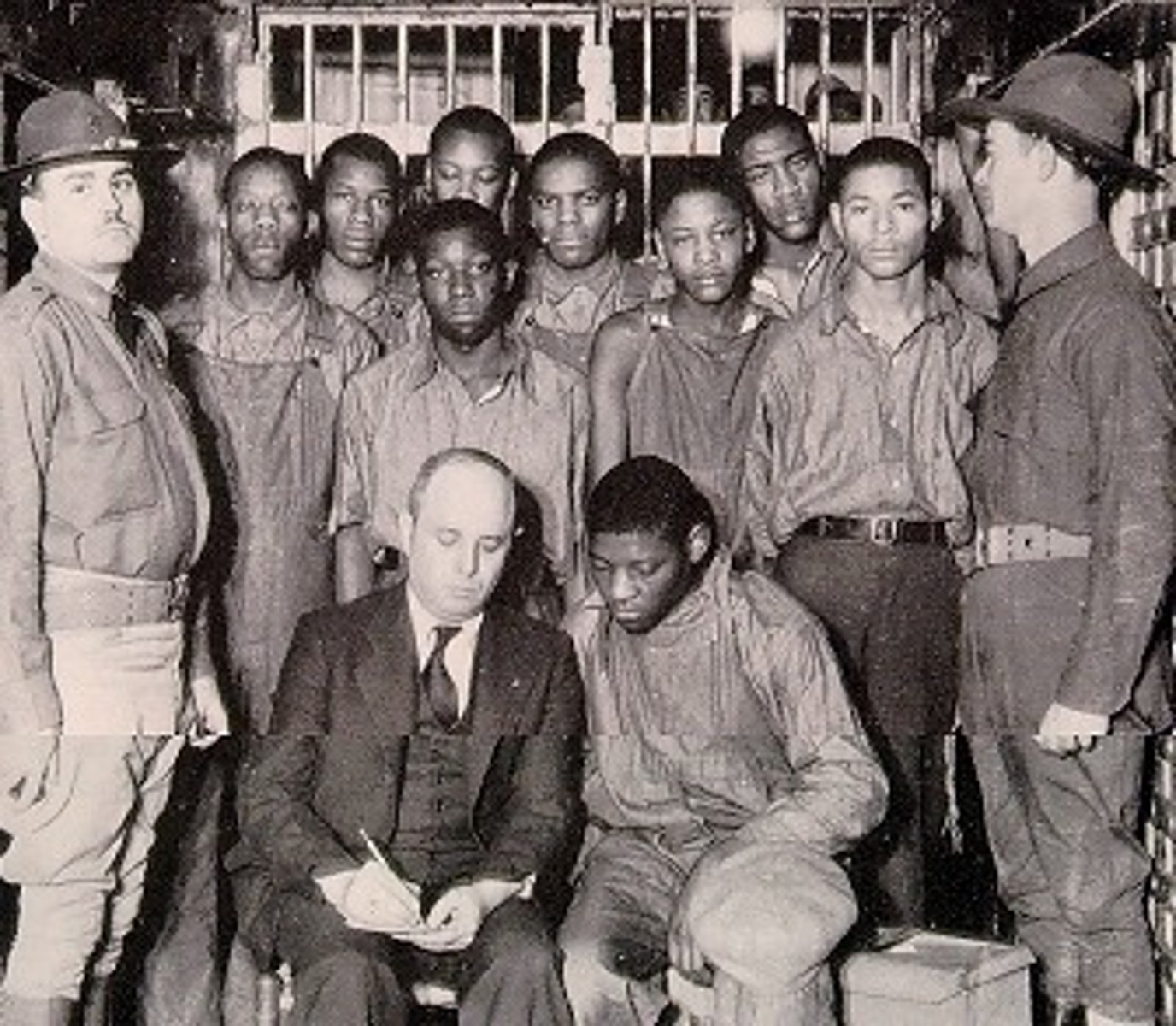

The Scottsboro Boys

Nine young black men who had been arrested for the rape of two white women in Alabama in 1931, and whose legal case, with the support of the the Communist Party and the NAACP, went on to become an an international cause célèbre and an often cited example of the miscarriage of justice in the U.S. legal system. Despite the weakness of the evidence against the nine accused young men, and the fact that one of the two accusers recanted, Alabama authorities three times put them on trial and three times won convictions. Landmark Supreme Court decisions overturned the first two verdicts and established legal principles that greatly expanded the definitions of civil liberties--that defendants have a constitutional right to effective legal representation, and that states cannot systematically exclude blacks from juries. But the court allowed the third set of convictions to stand.

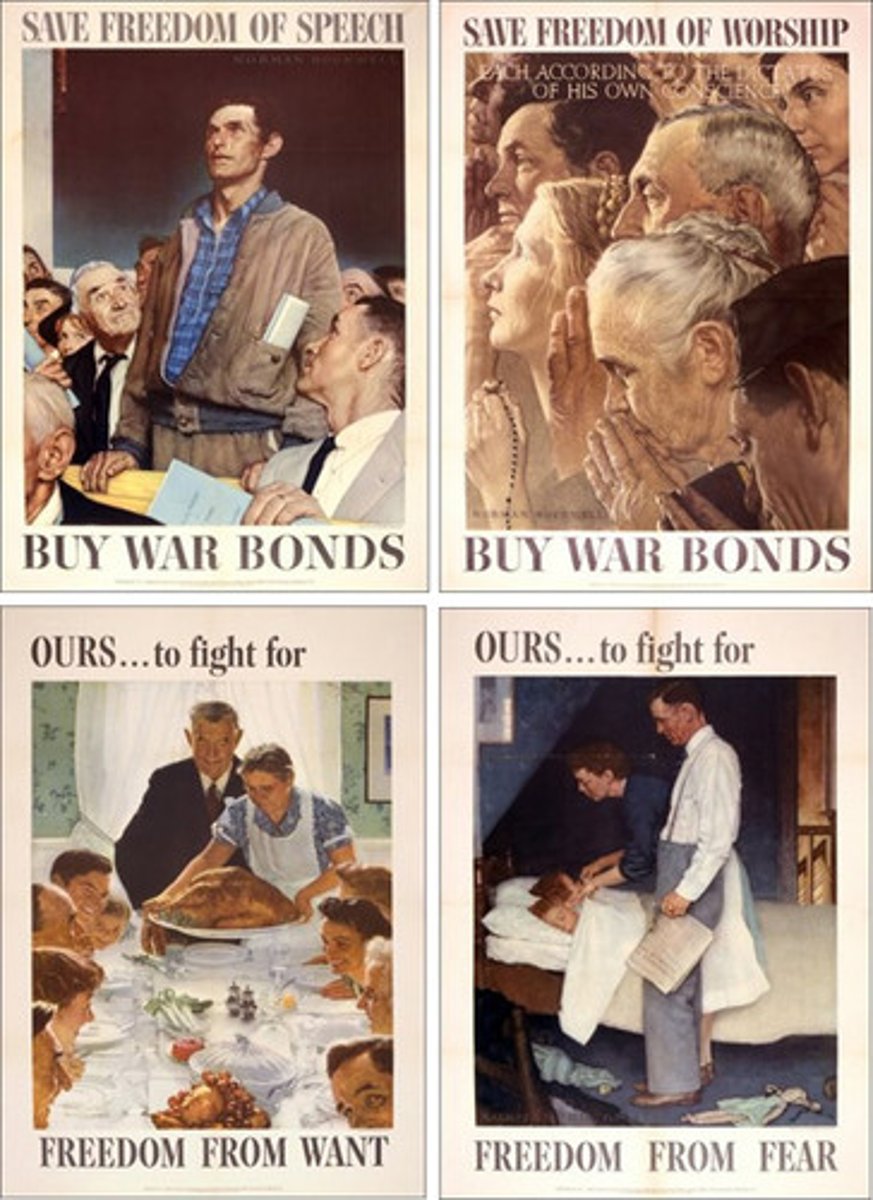

"The Four Freedoms"

"Freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear"--FDR's favorite statement, from 1941, of the Allied aims during Word War Two. In 1943, Norman Rockwell depicted them in a series of paintings of small-town life in America that became the most popular works of art produced during the era. As a means of generating support for the struggle, FDR's statement provided crucial language of national unity, but it also sometimes obscured divisions within American society.

The Good Neighbor Policy

During FDR's administration, this was the name given to U.S. foreign policy towards Latin America. A repudiation of the (Teddy) Roosevelt Corollary from earlier in the century, FDR's policy was premised on the principle of nonintervention and noninterference in Latin America. It had mixed results. The U.S. withdrew its troops from Haiti and Nicaragua, and accepted Cuba's repeal of the Platt Amendment, but it nevertheless dealt comfortably with undemocratic governments in Latin America that were friendly to U.S. business interests.

Isolationism

An approach to foreign policy in which a country tries to stay out of affairs of other nations, this became widely popular among Americans during the 1930s in part because of the Great Depression, and in part because many believed the U.S. involvement in WWI had been a mistake. This position was championed in the late 1930s by the America First Committee, which had very-well known leaders and hundreds of thousands of members.