social psych; week 8; prosocial behaviour

1/37

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

38 Terms

prosocial behaviour definitions

prosocial behaviour: acts that are positively viewed by society

has positive social consequences and contributes to the physical/ psychological wellbeing of another person

it is voluntary and intended to benefit others

being prosocial includes both being helpful and altruistic

what is considered prosocial is defined by society’s norms

types of prosocial behaviour

Helping behaviour – Acts that intentionally benefit someone else/group

•E.g., You find £10 and spend it = not helping behaviour; but if you gave £10 to someone who needs it = you have helped

Altruism – Acts that benefit another person rather than the self

Act is performed without expectation of one’s own gain

True altruism should be selfless, but it can be difficult to prove selflessness (Batson, 1981). Sometimes there are private rewards associated with acting pro socially (e.g., feeling good).

the beginnings of prosocial behaviour research

the Kitty Genovese Murder (1964)

one her way home she was attacked

tried to fight off attacker and screamed for help

37 people openly admitted to hearing her screaming but failed to act

why and when people help

Why and when people help

biological and evolutionary perspectives

mutualism

kin selection

social psychological perspectives

social norms

social learning

The biological and evolutionary perspective

Humans have an innate tendency to help others to pass our genes to the next generation

Helping kin improves their survival rates

Prosocial behaviour as a trait that potentially has evolutionary survival value

Animals also engage in prosocial behaviour

two explanations of prosocial behaviour in animals and humans

Stevens, Cushman, and Hauser (2005) have distinguished two explanations of prosocial behaviour in animals and humans:

mutualism- prosocial behaviour benefits the co-operator as well as others; a defector will do worse than a co-operator

Kin selection- prosocial behaviour is biased towards blood relatives because it helps their own genes

kin selection

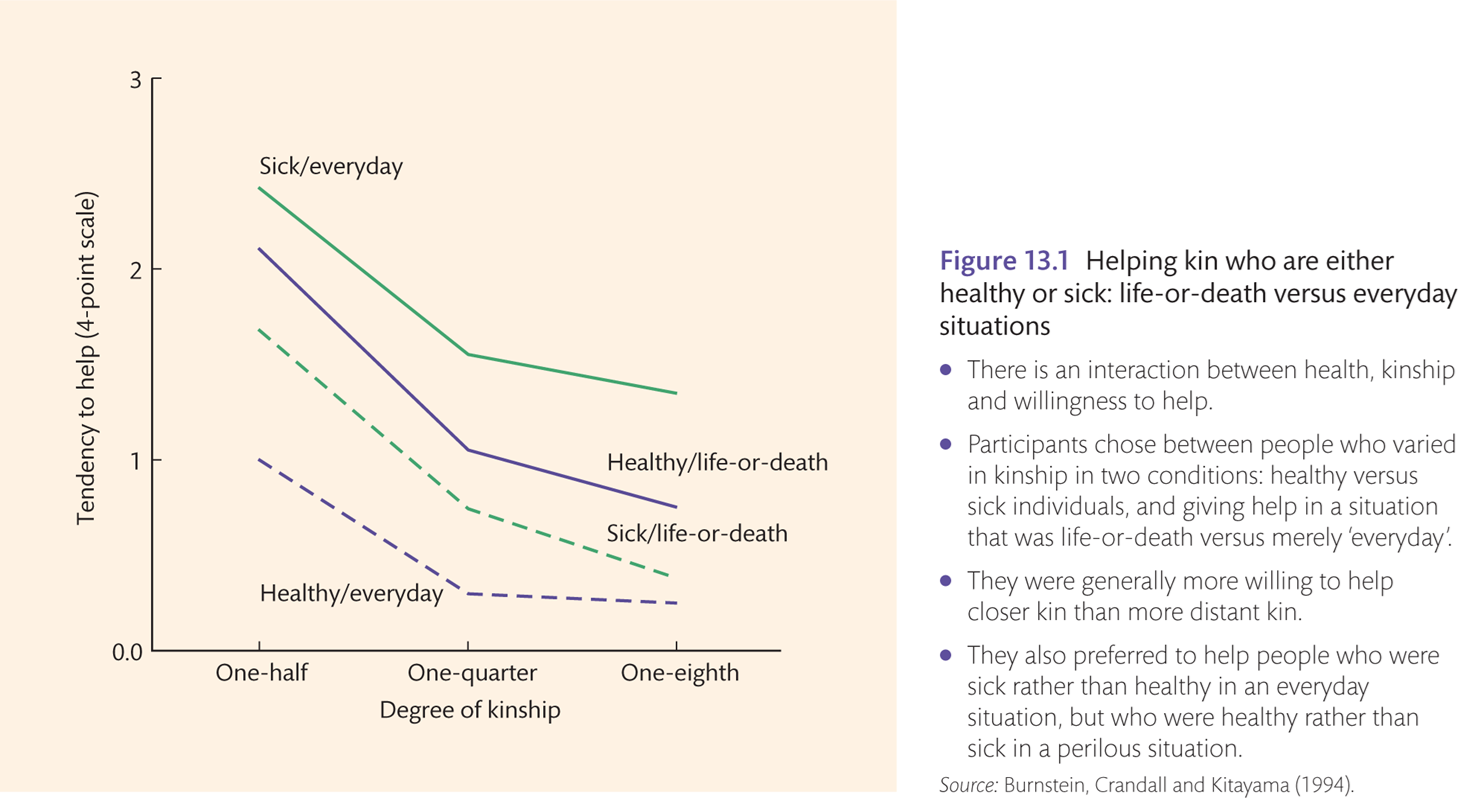

Burnstein et al (1994)

asked how likely they were to help in everyday and life or death situations if sick or healthy

people were more likely to help the sick in everyday situations, but more likely to help the healthy in life or death situations,

more likely to be willing to help if they were closer to them aka the closest kin get more help, keeping the bloodline going, keeping our genetic line going and helping those of value to us

social psychological accounts- norms

Often we help others because “something tells us” we should (e.g., we ought to return a wallet we found);

Societal norms play a key role in developing and sustaining prosocial behaviour (e.g. not littering); and these are learnt rather than innate.

“Social guidelines that establish what most people do in a certain context and what is socially acceptable” (Lay et al., 2020)

Behaving in line with social norms is often rewarded, leading to social acceptance.

Violating social norms can be punished and result in social rejection.

social norm types that may explain why people engage in prosocial behaviour

Reciprocity principle (Gouldner, 1960): we should help people who help us

Social responsibility (Berkowitz, 1972): we should help those in need independent of their ability to help us.

Just-world hypothesis (Lerner & Miller 1978): world is just and fair place, if we come across anyone who is undeservedly suffering, we help them to restore our belief in a just world.

how do children learn prosocial behaviour?

Social psychological accounts: Learning to be helpful

childhood is a critical period during which we learn prosocial behaviour

so how do children learn prosocial behaviour?

Giving instructions – Simply telling children to be helpful works (Grusec et al., 1978); telling children what is appropriate establishes an expectation and guide for later life. Though, if a child is told to be good but the preacher is inconsistent then it is pointless.

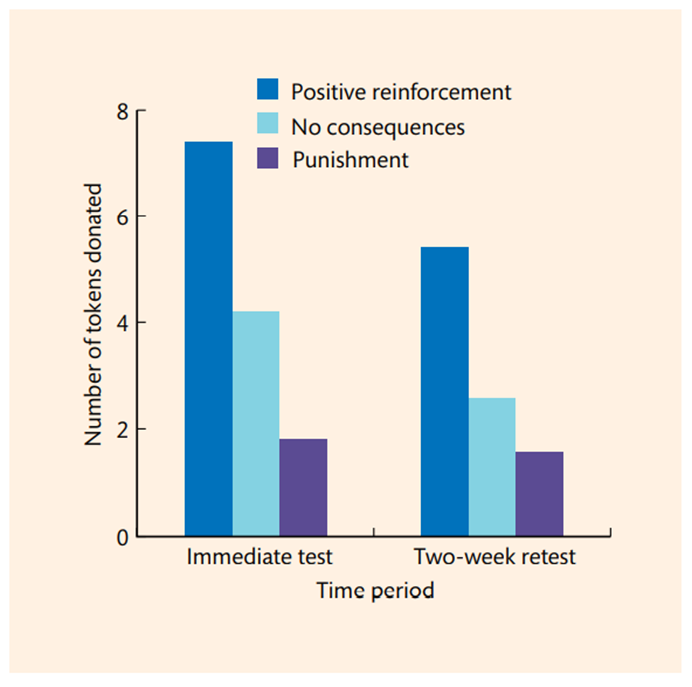

Using reinforcement – rewarding behaviour when young children are rewarded they are more likely to offer to help again; if children are not rewarded or punished they are less likely to offer to help again

Rushton and Teachman (1978)

•Children aged 8-11 observe an adult playing a game

•Adult is seen to donate tokens won in the game to a worse off child

•Conditions of: (1) positive reinforcement, (2) no consequences, and (3) negative reinforcement

Exposure to models – Rushton (1976) concluded from the review that modelling is more effective in shaping behaviour than reinforcement.

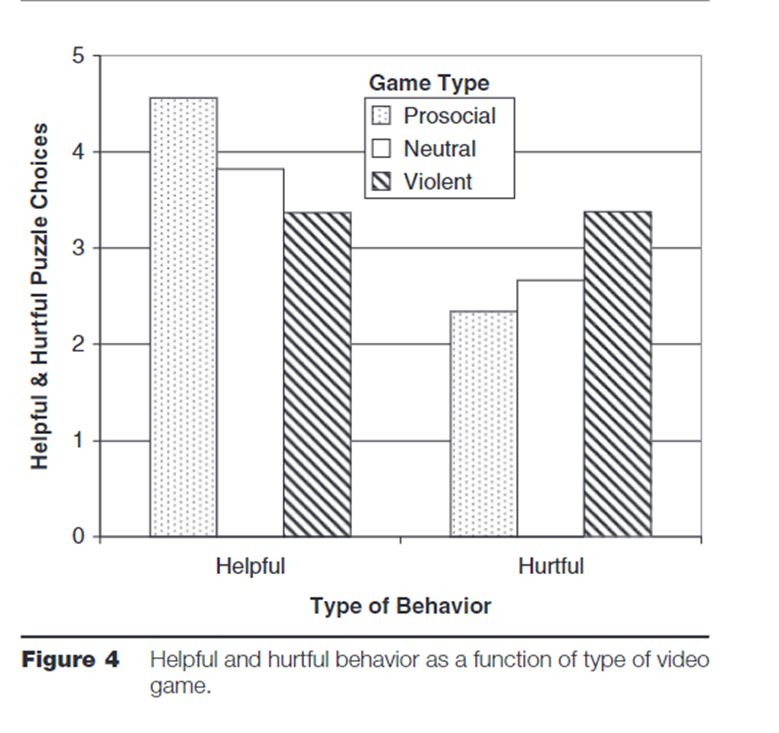

Gentile et al. (2009)

•Children aged 9-14 assigned to play prosocial, neutral or violent video games

Playing video games with prosocial content increased short term helping behaviour and decreased hurtful behaviour in a puzzle game

social psychological accounts: social learning theory

When a person observes a person and then models the behaviour, is this just a matter of mechanical imitation?

Bandura’s social learning theory (1973) argues against this –it is the knowledge of what happens to the model that determines whether or not the observer will help.

Hornstein (1970)

Conducted an experiment where people observed a model returning a lost wallet.

The model appeared either pleased to be able to help, displeased at helping, or no strong reaction.

Later the participant came across a ‘lost wallet’. Those who observed the pleasant condition helped the most; those who observed the negative helped the least.

Therefore modelling is not just imitation

the bystander effect/ apathy

people are less likely to help in an emergency when they are with others than when they are alone

Latané & Darley, 1968; Darley & Latane 1968:

•Emergency situations whilst completing a questionnaire: presence of smoke in the room or another participant suffering a medical emergency

•Presence of others: (1) confederates who do not intervene, (2) other participants or (3) alone

•Very few people intervened in the presence of others, especially when others did not intervene

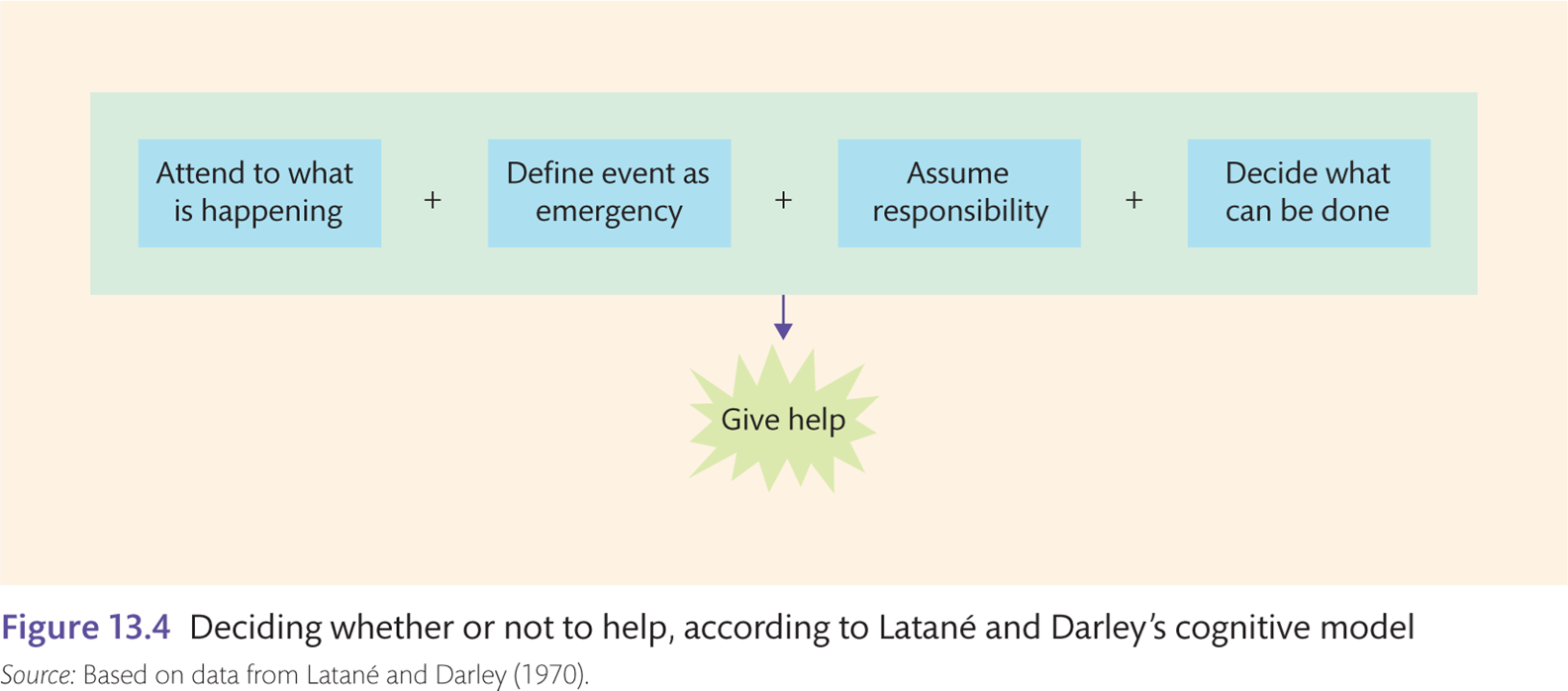

Latane and Darley’s cognitive model

processes contributing to the bystander effect

diffusion of responsibility

tendency of an individual to assume that others will take responsibility

audience inhibition

other onlookers may make the individual feel self-conscious about taking action; people do not want to appear foolish by overreacting

social influence

other people provide a model for action

if they’re unworried, the situation may seem less serious

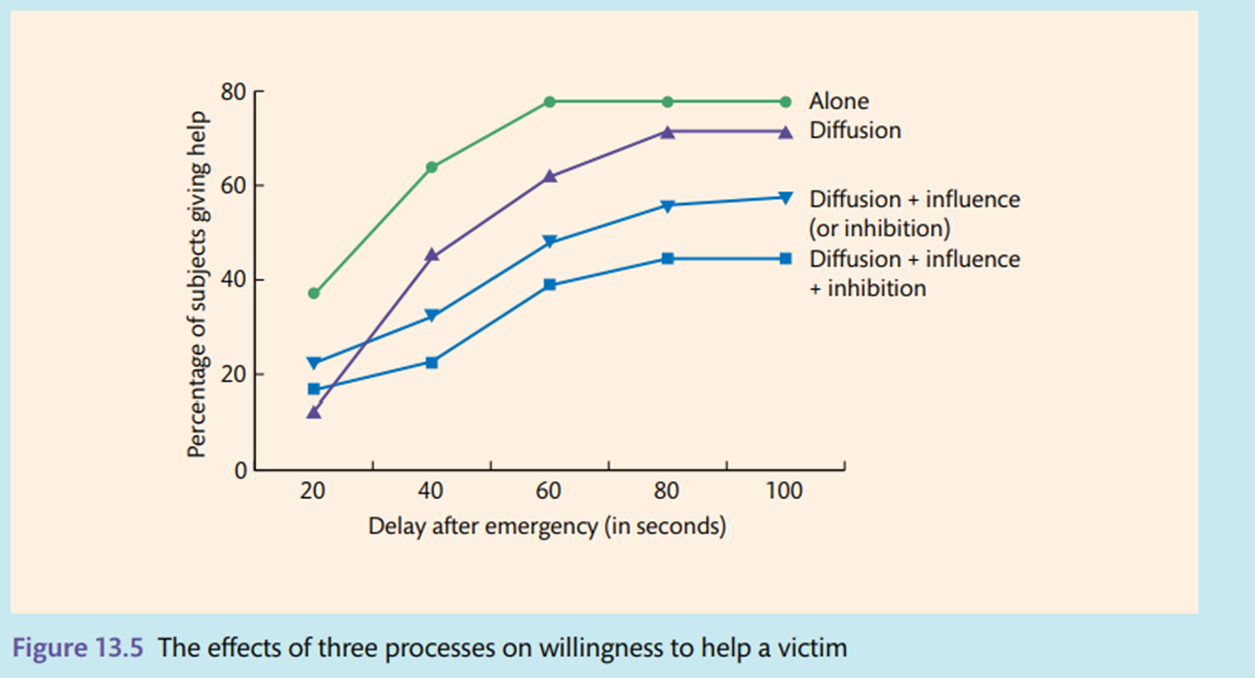

testing the processes underlying bystander apathy effect

Latané & Darley 1976

Methods:

Five conditions:

1.Control: Alone, cannot be seen by others nor can see others

2.Diffusion of responsibility: aware of another participant but cannot see them

3.Diffusion of responsibility+ social influence: aware of another participant, can see the other participant in the monitor, cannot be seen themselves

4.Diffusion of responsibility + audience inhibition: aware of another participant but cannot see them, but can be seen themselves

5.Diffusion of responsibility + audience inhibition + social influence: aware of another participant, can see them and aware they can be seen themselves

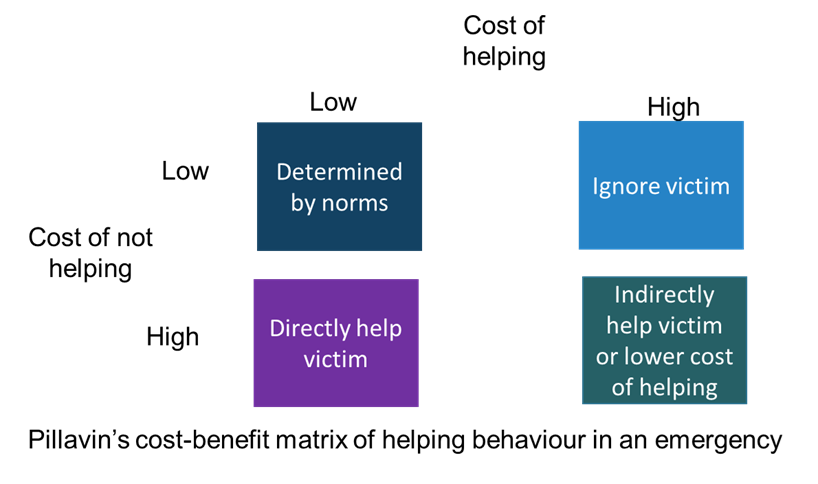

bystander calculus model

Piliavin et al., 1981

1.Physiological processes – an empathic response to someone in distress. The greater the arousal, the greater chance we will help (Gaertner & Dovidio, 1977).

•Emphatic concern is triggered when we believe we are similar to the victim and can relate to them, we are more likely to help the person (Batson & Coke, 1981)

Labelling the arousal– we label this arousal as an emotion (e.g. distress, anger, fear).

•Personal distress at seeing someone else suffer- helping behaviour motivated by desire to reduce own negative emotional experience

Evaluating the consequences of helping:

Cost benefit analysis.

Costs of helping:

•Time and effort (Darley & Batson, 1973)

•but also personal risk

Costs of not helping:

•Empathy costs of not helping can cause distress to a bystander who empathises with the victim

•Personal costs of not helping a victim can cause distress (e.g., feeling guilt or blame)

evidence for the bystander calculus model

Shotland & Straw 1976

Experiment 1:

•Participants witness a man and a woman fighting

•Condition: married couple versus strangers

•Intervention rate is measured: 65% in the strangers condition vs 19% in the married couple condition.

•Why?

contradicting the bystander effect

Philpot et al (2020)

•CCTV recordings of 219 street disputes in three cities in different countries — Lancaster, England; Amsterdam, Netherlands; and Cape Town, South Africa.

•At least one bystander intervened in 90% of cases

•Contrary to the previous research, presence of others increased likelihood of helping

Since there has been admittance that the story of Genovese's murder had been exaggerated by the media. Reporting was "flawed“ and "grossly exaggerated the number of witnesses and what they had perceived"

perceiver centred determinants of helping personality- is there actually a thing of an altruistic personality?

Bierhoff, Klein & Kramp 1991:

•People who helped in a traffic accident vs those who did not help

•Helpers and non-helpers distinguished on:

•the norm of social responsibility

•internal locus of control

•greater dispositional empathy

Evidence is correlational and it’s not clear whether personality traits cause helping behaviour

perceiver centred determinants of helping: mood

individuals who feel good are more likely to help someone in need compared to those who feel bad

•Holloway et al., 1977: receiving good news-> increased willingness to help

•Isen (1970) found that teachers who were more successful on a task were more likely to contribute later to a school fundraising event. In fact, those who did well donated 7 times as much as others!

Though mood effects may be short-lived:

•Isen, Clark, Schwartz 1976: increased willingness to help a stranger only within the first seven minutes of positive mood induction

Perceiver centred determinants of helping: competence

Feeling competent to deal with an emergency makes it more likely that help will be given; there is the awareness that ‘I know what I am doing’ (Korte, 1971).

Specific kinds of competence have increased helping in these contexts:

People were more willing to help others move electrically charged objects if they were told they had a high tolerance for electric shocks (Midlarsky & Midlarsky, 1976);

People were more likely to help to recapture a dangerous lab rat if they were told they were good at handling rats (Schwartz & David, 1976).

Certain skills are perceived as being relevant to some emergencies, e.g., in reacting to a stranger who is bleeding, first-aid trained individuals were more likely to intervene (Shotland & Heinold, 1985).

Recipient centred determinants of prosocial behaviour: group membership

Levine et al., 2005 study 1

•45 Manchester United (ManU) fans

•Participants directed to take a short walk during which they witness an emergency incident

•Group membership is manipulated

•confederate wears Man U, Liverpool FC or plain sports top

•Rate of helping the confederate measured

•ManU fans were more likely to help other ManU fans than Liverpool FC fans or those not supporting a football team

Helping behaviour increased for in group members

Levine et al., 2005 study 2

•Same design as the first study

•Participants were told they were taking part in a study about football fans

•Focusing on the positives of being a football fan

•Measured helping behaviour to confederate who is wearing ManU, Liverpool FC, or plain top.

•Equally likely to help confederate wearing ManU or Liverpool FC top.

•those wearing a plain top were less likely to be helped.

Broadening the boundaries of social categories may increase helping behaviour

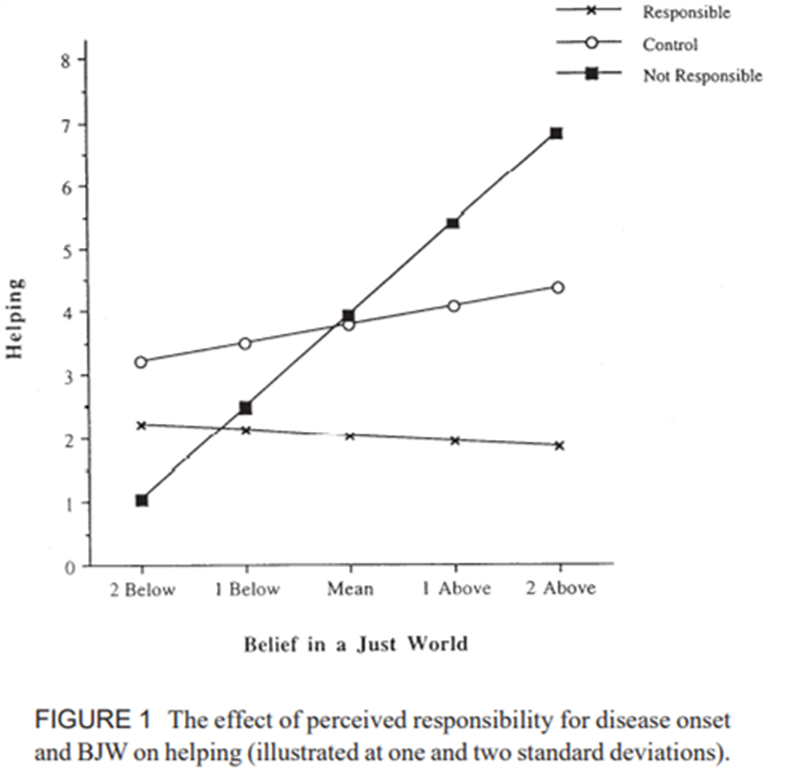

Recipient centred determinants of prosocial behaviour: responsibility for misfortune

people are generally more likely to help people who are not responsible for their misfortune (e.g. just world hypothesis)

Just world hypothesis: the world is a just and fair place and, if we come across anyone who is undeservedly suffering we help them to restore our belief in a just world.

Turner DePalma et al., 1999

•98 participants read booklet about a fictional disease

•Disease was either caused by a genetic anomality or an action of the individual or no information was given

•Measured participants’ belief in a just world

•Offered twelve helping options with differing commitment levels

•Helping behaviour was significantly increased when it was believed that the person was not responsible for illness

•People with high belief in a just world helped more only when the person was believed not to be responsible for their illness.

We have been focusing on the helper but what about the recipient. Do they always want help?

Wakefield, Hopkins, and Greenwood (2012)

•Female students were made aware that women may be stereotyped by men as dependant, and were then placed in a situation where they needed help;

•Asked to solve a set of anagrams

•Those made aware of the dependency stereotype (compared to controls who were not) were less willing to seek help;

•Those that did seek help felt worse the more help they sought.

Receiving help can be interpreted negatively if it confirms a negative stereotype about the recipient

helping behaviour

Helping behaviour is a subcategory of prosocial behaviour. Helping is intentional, and it benefits another living being or group.

If you accidentally drop a ten-pound note and someone finds it and spends it, you have not performed a helping behaviour. But if you gave ten pounds to Connie who really needed it, you have helped her.

On the other hand, making a large public donation to a charity because you wanted to appear generous is not helping behaviour. Some corporate donations to a good cause may be driven by product promotion; e.g. in pursuit of a long-term increase in profit.

Helping can even be antisocial; e.g. overhelping, when giving help is designed to make others look inferior

altruism

Altruism is another subcategory of prosocial behaviour. It refers to an act that is meant to benefit another person rather than oneself.

True altruism should be selfless, but it can be difficult to prove true selflessness (Batson, 1991). For example, can we ever really know that an act does not stem from a long-term ulterior motive, such as ingratiation?

Ervin Staub (1977) noted that there are sometimes ‘private’ rewards associated with acting prosocially, such as feeling good or being virtuous. There is a considerable debate over how magnanimous human nature really is

empathy and arousal

A common experience before acting prosocially is a state of arousal followed by empathy. Empathy is an emotional response to someone else’s distress, a reaction to witnessing a disturbing event. Adults and children respond empathically to signs that a person is troubled, which implies that watching someone suffer is unpleasant.

Have you ever looked away when a film shows someone being tortured? Censors forewarn us if a film depicts scenes of violence, and most of us have been in an audience when a few tears are not far away. Even infants one or two days old can respond to the distress of another infant. In real life, people often fail to act prosocially because they are actively engaged in avoiding empathy

however, when we try to help are we just trying to reduce our own discomfort?

The extra ingredient is empathy, an ability to identify with someone else’s experiences, particularly their feelings (Krebs, 1975). Empathy is related to perspective taking, being able to see the world through others’ eyes, but it is not the same thing. Generally speaking, empathy is affect and feeling-based (I feel your pain), whereas perspective taking is cognition based (I see your pain)

personal cost of not helping

self-blame

public censure

certain characteristics of the person in distress,

for instance, the greater the victim’s need for help, the greater the costs of not helping. If you believe a victim might die if you do not help, the personal costs are likely to be high.

If a tramp in the street asked you for money to buy alcohol, the personal costs of refusing might not be high; but if the request was for money for food or medicine, the costs might be quite high.

what increases the likelihood of a bystander helping?

the more similar the victim is to the bystander, the more likely the bystander is to help. Similarity causes greater physiological arousal in bystanders and thus greater empathy costs of not helping. Similar victims may also be friends, for whom the costs of not helping would be high.

why does the bystander-calculus model the Genovese case?

The bystander-calculus model suggests that, although the onlookers would have been aroused and felt personal distress and empathic concern, the empathy costs and personal costs were not sufficient. Personal costs, in particular, may have deterred people from intervening. What if they got killed themselves? The costs of not helping could be either high or low, depending on how people interpreted the situation: for example, was it merely a heated marital spat? Situational influences are significantly involved when adults decide whether to help in an emergency

gameplayer and the media

Lawrence Rosenkoetter (1999) found that children who watched television comedies that included a moral lesson engaged more frequently in prosocial behaviour, provided they understood the principle involved.

Gentile et al investigated the effects of playing video games featuring prosocial acts on prosocial behaviour measured by questionnaires

In a series of three developmental studies, three age groups of Singaporeans, Americans and Japanese played both prosocial and violent video games. A central finding was that when the video content was prosocial, the participants acted in more helpful ways, but when it was violent, they acted in more hurtful ways. These effects were consistent across cultures and age groups.

The effects of the media can be broadened to include music.

For example, Tobias Greitmeyer (2009) found that both German and British participants who listened to prosocial songs were more willing to offer help to other people, without request. Greitmeyer and Osswald (2010) have reported that viewing prosocial videos increased the rate of helping behaviour; and these videos made prosocial cognitions more accessible. Consequently, they argued that the General Aggression Model (GAM) could be developed into a General Learning Model (GLM)

the impact of attribution

People make causal attributions for helping. To continue being helpful on more than one occasion requires a person to internalise the idea of ‘being helpful’.

If we are wondering whether to offer help to someone in need, we usually try to figure out who or what this person might be. One reason why we might do this is to make the world seem like a place where bad things happen to bad people and good things to good people – the just-world hypothesis.

Therefore, if some victims deserve their fate, we can think ‘Good, they had that coming to them!’ and not help them. Some witnesses in the Kitty Genovese case may believe that it was her fault for being out so late.

A necessary precondition of actually helping is to believe that the help will be effective. Miller (1977) isolated two factors that can convince a would-be helper: (1) the victim is a special case rather than one of many, and (2) the need is temporary rather than persisting. Each of these allows us to decide that giving aid ‘right now’ will be effective.

Peter Warren and Iain Walker (1991) showed that if the needs of a person in distress can be specified, others can use this information to determine if giving help is justified. In a field study with 2,500 recipients, a letter mail-out solicited donations for a refugee family from Sudan. Cover letters with slightly different wording were used. More donations were recorded when the letter highlighted that: (1) the donation was restricted to this particular family rather than being extended to others in Sudan; and (2) the family’s need was only short term.

the bystander effect: Latane and Darley’s cognitive model

Bibb Latané and John Darley asked, where several bystanders are present, there should be a correspondingly greater probability that someone will help? Consider first the elements of an emergency situation:

it can involve danger, for person or property

it is an unusual event, rarely encountered by the ordinary person

it can differ widely in nature, from a bank on fire to a pedestrian being mugged

it is not foreseen, so that prior planning of how to cope is improbable

it requires instant action, so that leisurely consideration of options is not feasible

Latané and Darley noted that it would be easy to label the failure to help in an emergency as apathy – an uncaring response to the problems of others. However, they reasoned that the apparent lack of concern by the witnesses in the Genovese case conceal other processes.

Latané and Darley suggested that the presence of others can inhibit people from responding to an emergency: the more people, the slower the response.

Even worse, many of the people who did not respond were persuaded that if others were passive, there was no emergency.

processes contributing to bystander apathy

is the individual aware that others are present?

can the individual actually see or hear the others and be aware of how they are reacting?

can these others monitor the behaviour of the individual?

actual processes include:

diffusion of responsibility

audience inhibition

social influence

diffusion of responsibility

Think back to social loafing, where a person who is part of a group often offloads responsibility for action to others. In the case of an emergency, the presence of other onlookers provides the opportunity to transfer responsibility for acting, or not acting, to them. The communication channel does not imply that the individual can be seen by the others or can see them. It is necessary only that they be available, somewhere, for action. People who are alone are most likely to help a victim because they believe they carry the entire responsibility for action. If they do not act, nobody else will. Ironically, the presence of just one other witness allows diffusion of responsibility to operate among all present.

audience inhibition

Other onlookers can make people self-conscious about taking action; people do not want to appear foolish by overreacting. In the context of prosocial behaviour, this process is sometimes referred to as a fear of social blunders . Have you felt a dread of being laughed at for misunderstanding little crises involving others? What if it is not as it seems? What if someone is playing a joke? The communication channel implies that the others can see or hear the individual, but it is not necessary that they can be seen

social influence

Other onlookers provide a model for action. If they are passive and unworried, the situation may seem less serious. The communication channel implies that the individual can see the others, but not vice versa.

the three-in-one experiment

By the use of TV monitors and cameras, participants were induced to believe that they were in one of four conditions with respect to other onlookers. They could (1) see and be seen; (2) see, but not be seen; (3) not see, but be seen; or (4) neither see nor be seen. This complexity was necessary to allow for the consequences of sequentially adding social influence and audience inhibition effects to that of diffusion of responsibility. We should note here that diffusion of responsibility must always be involved if a bystander is, or is thought to be, present at the moment of the emergency. However, the additive effect of another process can be assessed and then compared with the effect of diffusion acting on its own.

limits to the bystander effect

Bystanders who are strangers to each other inhibit helping even more because communication between them is slower. When bystanders are known to each other, there is much less inhibition of prosocial behaviour than in a group of strangers. However, Jody Gottlieb and Charles Carver (1980) showed that even among strangers, inhibition is reduced if they know that there will be an opportunity to interact later and possibly explain their actions. Overall, the bystander effect is strongest when the bystanders are anonymous strangers who do not expect to meet one another again, which was most likely the situation in the Genovese case. Catherine Christy and Harrison Voigt (1994) found that bystander apathy is reduced if the victim is an acquaintance, friend or relative or is a child being abused in public

the studies above have much in common: bystanders who are strangers and who are present by chance at an emergency generally do not constitute a group- friends do

For example, if the victim is female and the bystanders are male, gender becomes a salient category, males are now a group, and the sex-role stereotype of the chivalrous male can ‘spring into action’. The key point is that normative expectations about how to respond in a particular situation come into play if a social identity is primed by the context. In the absence of a salient identity to guide appropriate action, people are very much on their own to figure out what to do

the influence of mood states on the action of helping

Good mood:

Alice Isen

found that teachers more successful on a task were more likely to contribute later to a school fundraising drive. Those who had done well donated seven times as much as the others! Isen suggested that doing well creates a ‘warm glow of success’, which makes people more likely to help.

People who hear good news on the radio express greater attraction towards strangers and greater willingness to help than people who hear bad news, and people are in better moods and are more helpful on sunny, temperate days than on overcast, cold days. Even experiences such as reading aloud statements expressing elation, or recalling pleasant events from our childhood, can increase the rate of helping.

Bad mood

They concentrate on themselves, their problems and worries (Berkowitz, 1970), are less concerned with the welfare of others and help others less (Weyant, 1978). Berkowitz (1972b) showed that self-concern lowered the rate and amount of helping among students awaiting the outcome of an important exam.

Darley and Batson (1973) led seminary students, who were due to give a speech, to think they were quite late, just in time or early. They then had the opportunity to help a man who had apparently collapsed in an alley. The percentages that helped were: quite late, 10 per cent; just in time, 45 per cent; and early, 63 per cent.