social psych; week 8; prosocial behaviour

Definitions

prosocial behaviour: acts that are positively viewed by society

has positive social consequences and contributes to the physical/ psychological wellbeing of another person

it is voluntary and intended to benefit others

being prosocial includes both being helpful and altruistic

what is considered prosocial is defined by society’s norms

Types of prosocial behaviour

Helping behaviour – Acts that intentionally benefit someone else/group

•E.g., You find £10 and spend it = not helping behaviour; but if you gave £10 to someone who needs it = you have helped

Altruism – Acts that benefit another person rather than the self

Act is performed without expectation of one’s own gain

True altruism should be selfless, but it can be difficult to prove selflessness (Batson, 1981). Sometimes there are private rewards associated with acting pro socially (e.g., feeling good).

Examples of prosocial behaviour

The beginnings of prosocial behaviour research

the Kitty Genovese Murder (1964)

one her way home she was attacked

tried to fight off attacker and screamed for help

37 people openly admitted to hearing her screaming but failed to act

Why and when people help

biological and evolutionary perspectives

mutualism

kin selection

social psychological perspectives

social norms

social learning

The biological and evolutionary perspective

Humans have an innate tendency to help others to pass our genes to the next generation

Helping kin improves their survival rates

Prosocial behaviour as a trait that potentially has evolutionary survival value

Animals also engage in prosocial behaviour

Stevens, Cushman, and Hauser (2005) have distinguished two explanations of prosocial behaviour in animals and humans:

mutualism- prosocial behaviour benefits the co-operator as well as others; a defector will do worse than a co-operator

Kin selection- prosocial behaviour is biased towards blood relatives because it helps their own genes

Kin selection

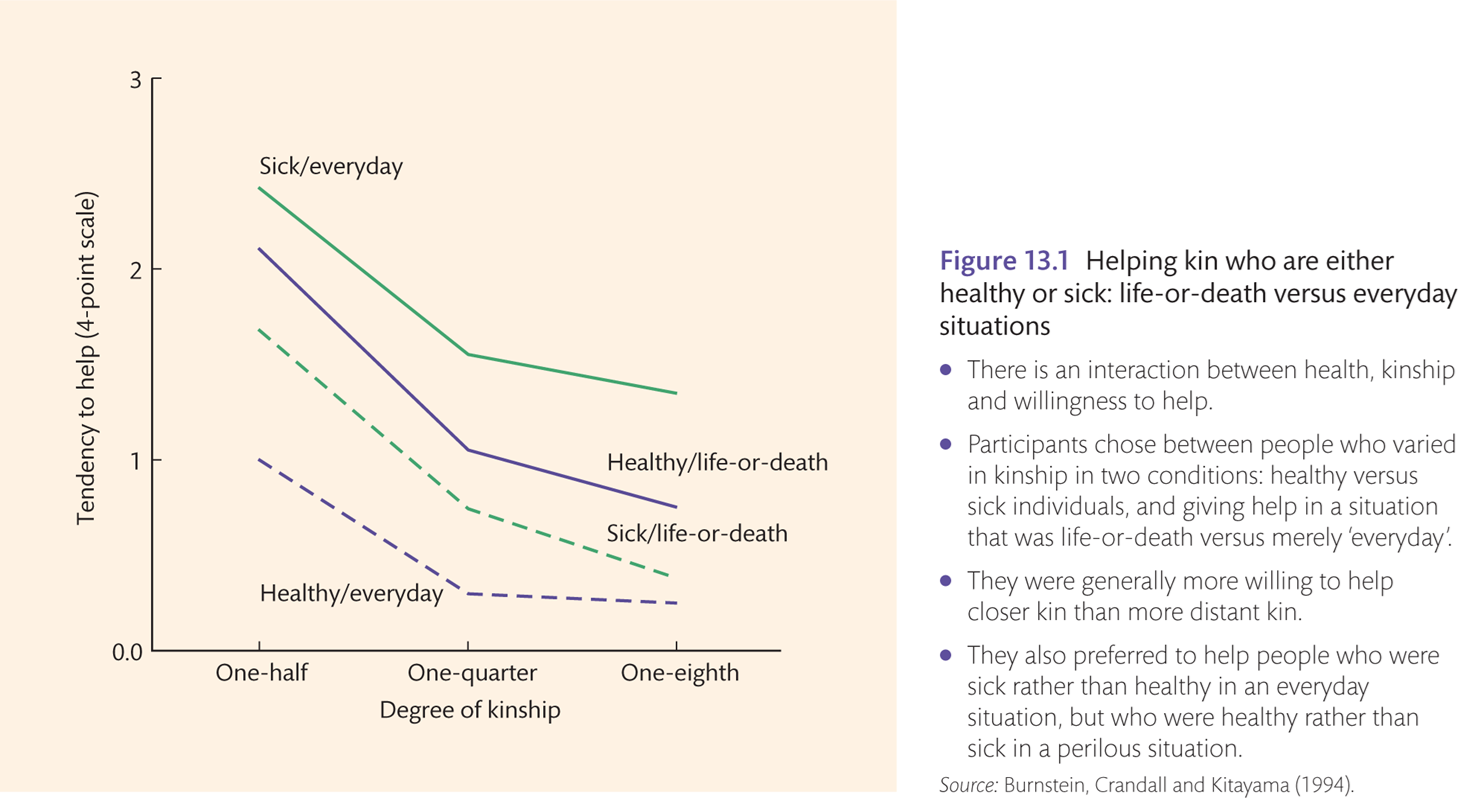

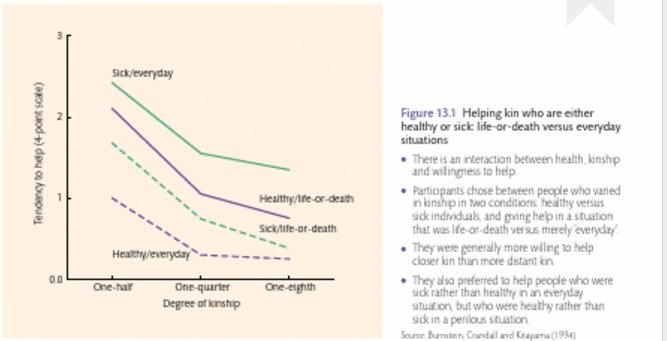

asked how likely they were to help in everyday and life or death situations if sick or healthy

people were more likely to help the sick in everyday situations, but more likely to help the healthy in life or death situations,

more likely to be willing to help if they were closer to them aka the closest kin get more help, keeping the bloodline going, keeping our genetic line going and helping those of value to us

Social psychological accounts

Norms:

Often we help others because “something tells us” we should (e.g., we ought to return a wallet we found);

Societal norms play a key role in developing and sustaining prosocial behaviour (e.g. not littering); and these are learnt rather than innate.

“Social guidelines that establish what most people do in a certain context and what is socially acceptable” (Lay et al., 2020)

Behaving in line with social norms is often rewarded, leading to social acceptance.

Violating social norms can be punished and result in social rejection.

Three social norms may explain why people engage in prosocial behaviour

Reciprocity principle (Gouldner, 1960): we should help people who help us

Social responsibility (Berkowitz, 1972): we should help those in need independent of their ability to help us.

Just-world hypothesis (Lerner & Miller 1978): world is just and fair place, if we come across anyone who is undeservedly suffering, we help them to restore our belief in a just world.

Social psychological accounts: Learning to be helpful

childhood is a critical period during which we learn prosocial behaviour

How do children learn prosocial behaviour?

Giving instructions – Simply telling children to be helpful works (Grusec et al., 1978); telling children what is appropriate establishes an expectation and guide for later life. Though, if a child is told to be good but the preacher is inconsistent then it is pointless.

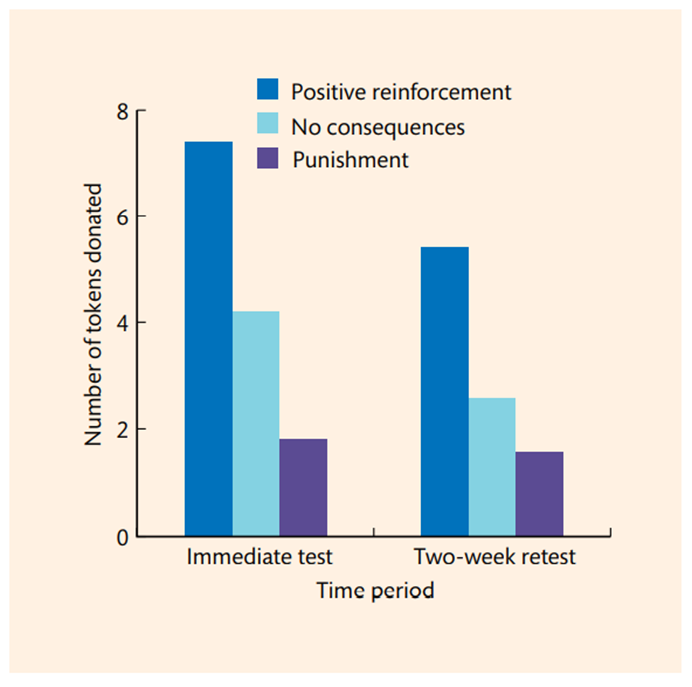

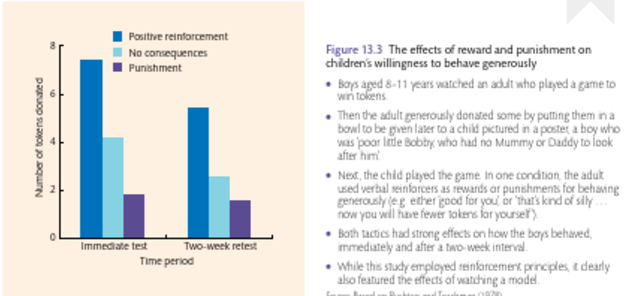

Using reinforcement – rewarding behaviour when young children are rewarded they are more likely to offer to help again; if children are not rewarded or punished they are less likely to offer to help again

Rushton and Teachman (1978)

•Children aged 8-11 observe an adult playing a game

•Adult is seen to donate tokens won in the game to a worse off child

•Conditions of: (1) positive reinforcement, (2) no consequences, and (3) negative reinforcement

Exposure to models – Rushton (1976) concluded from the review that modelling is more effective in shaping behaviour than reinforcement.

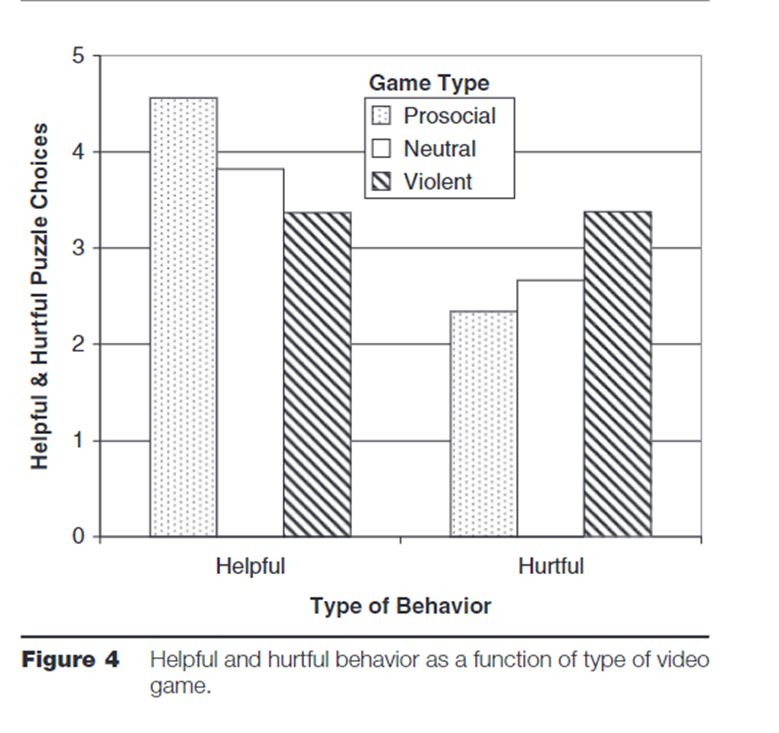

Gentile et al. (2009)

•Children aged 9-14 assigned to play prosocial, neutral or violent video games

Playing video games with prosocial content increased short term helping behaviour and decreased hurtful behaviour in a puzzle game

Social psychological accounts: Social learning theory (SLT)

When a person observes a person and then models the behaviour, is this just a matter of mechanical imitation?

Bandura’s social learning theory (1973) argues against this –it is the knowledge of what happens to the model that determines whether or not the observer will help.

Hornstein (1970)

Conducted an experiment where people observed a model returning a lost wallet.

The model appeared either pleased to be able to help, displeased at helping, or no strong reaction.

Later the participant came across a ‘lost wallet’. Those who observed the pleasant condition helped the most; those who observed the negative helped the least.

Therefore modelling is not just imitation

The bystander effect/ apathy

people are less likely to help in an emergency when they are with others than when they are alone

Latané & Darley, 1968; Darley & Latane 1968:

•Emergency situations whilst completing a questionnaire: presence of smoke in the room or another participant suffering a medical emergency

•Presence of others: (1) confederates who do not intervene, (2) other participants or (3) alone

•Very few people intervened in the presence of others, especially when others did not intervene

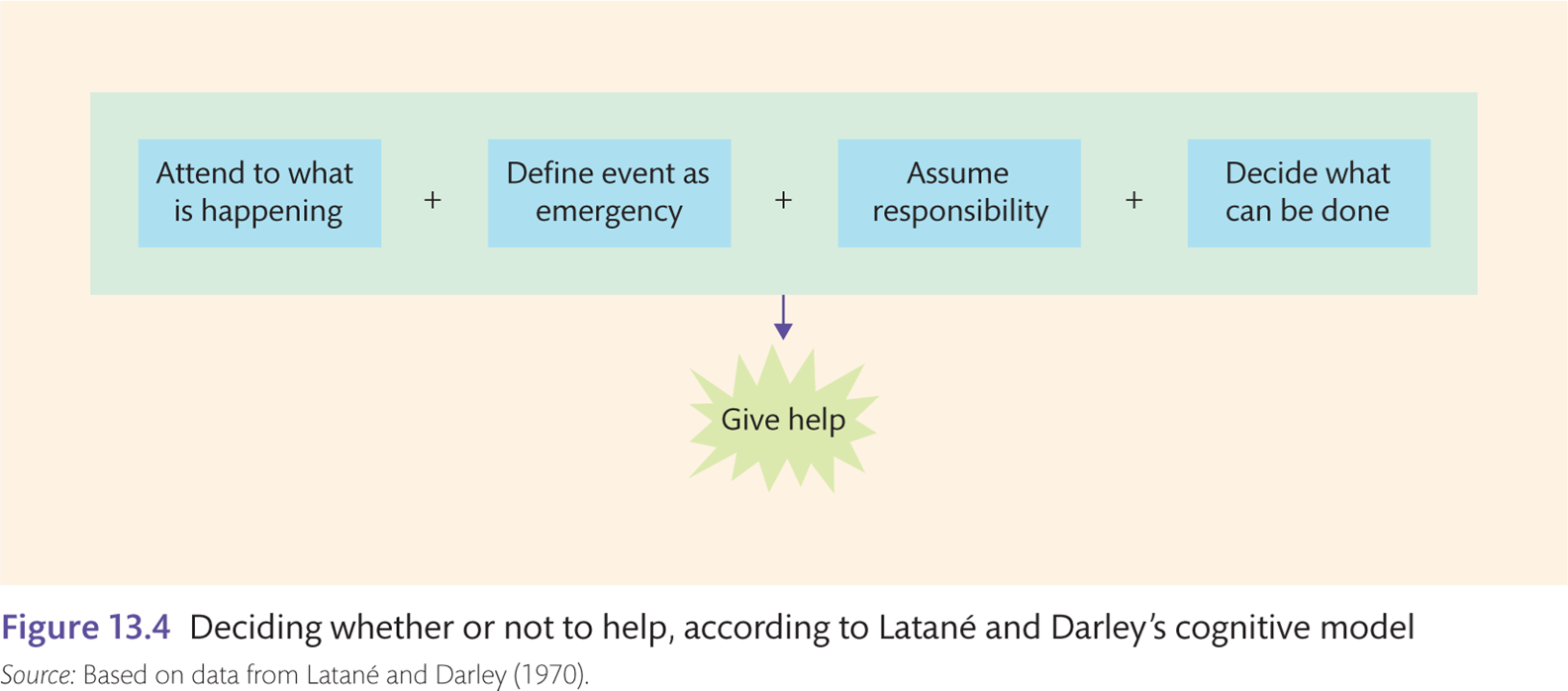

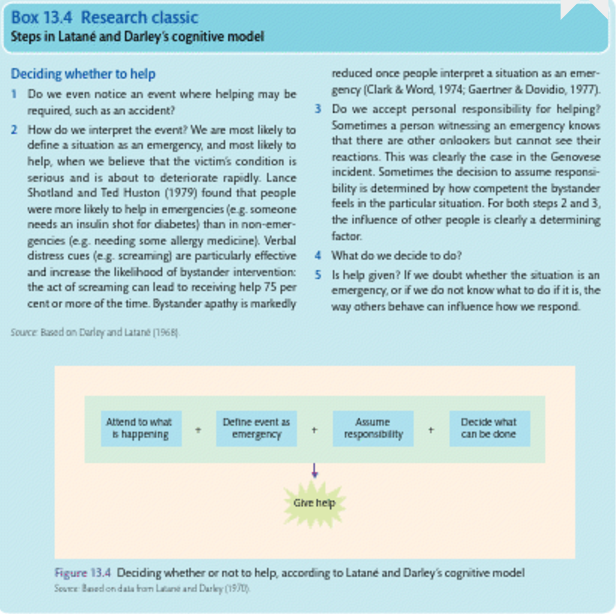

Latane and Darley’s cognitive model

Processes contributing to the bystander effect

diffusion of responsibility

tendency of an individual to assume that others will take responsibility

audience inhibition

other onlookers may make the individual feel self-conscious about taking action; people do not want to appear foolish by overreacting

social influence

other people provide a model for action

if they’re unworried, the situation may seem less serious

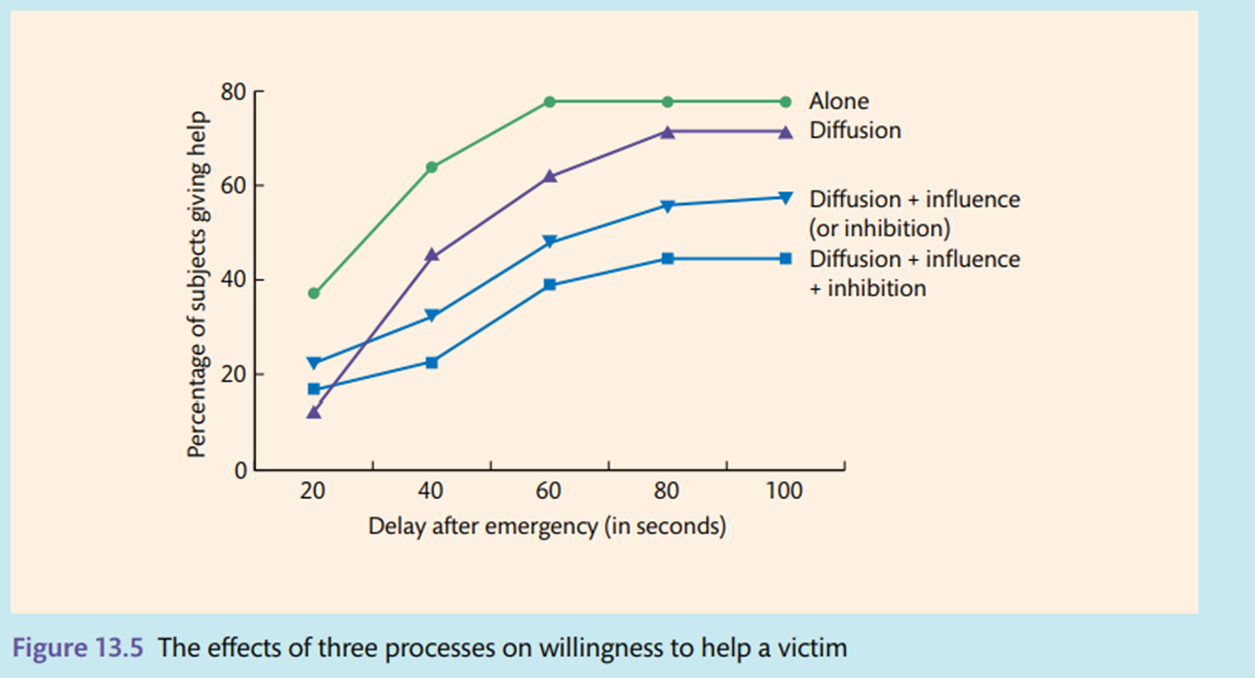

Testing the processes underlying bystander apathy effect

Latané & Darley 1976

Methods:

Five conditions:

1.Control: Alone, cannot be seen by others nor can see others

2.Diffusion of responsibility: aware of another participant but cannot see them

3.Diffusion of responsibility+ social influence: aware of another participant, can see the other participant in the monitor, cannot be seen themselves

4.Diffusion of responsibility + audience inhibition: aware of another participant but cannot see them, but can be seen themselves

5.Diffusion of responsibility + audience inhibition + social influence: aware of another participant, can see them and aware they can be seen themselves

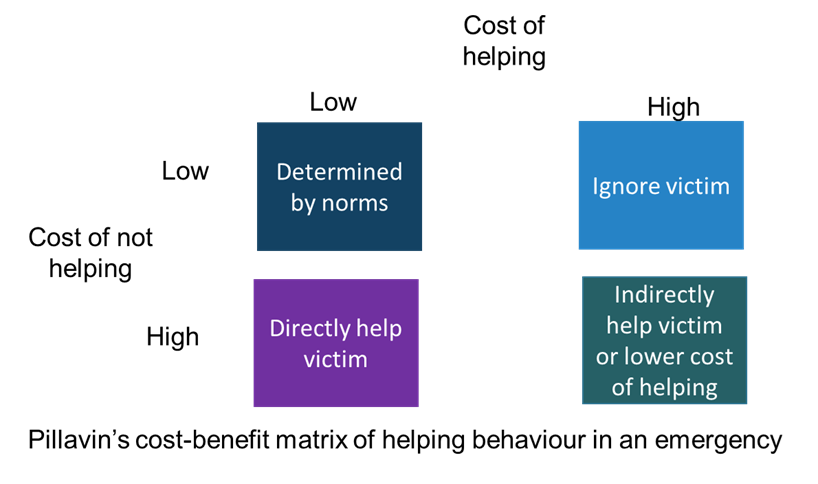

Bystander calculus model

Piliavin et al., 1981

1.Physiological processes – an empathic response to someone in distress. The greater the arousal, the greater chance we will help (Gaertner & Dovidio, 1977).

•Emphatic concern is triggered when we believe we are similar to the victim and can relate to them, we are more likely to help the person (Batson & Coke, 1981)

Labelling the arousal– we label this arousal as an emotion (e.g. distress, anger, fear).

•Personal distress at seeing someone else suffer- helping behaviour motivated by desire to reduce own negative emotional experience

Evaluating the consequences of helping:

Cost benefit analysis.

Costs of helping:

•Time and effort (Darley & Batson, 1973)

•but also personal risk

Costs of not helping:

•Empathy costs of not helping can cause distress to a bystander who empathises with the victim

•Personal costs of not helping a victim can cause distress (e.g., feeling guilt or blame)

Evidence for the bystander calculus model:

Shotland & Straw 1976

Experiment 1:

•Participants witness a man and a woman fighting

•Condition: married couple versus strangers

•Intervention rate is measured: 65% in the strangers condition vs 19% in the married couple condition.

•Why?

contradicting the bystander effect

Philpot et al (2020)

•CCTV recordings of 219 street disputes in three cities in different countries — Lancaster, England; Amsterdam, Netherlands; and Cape Town, South Africa.

•At least one bystander intervened in 90% of cases

•Contrary to the previous research, presence of others increased likelihood of helping

Since there has been admittance that the story of Genovese's murder had been exaggerated by the media. Reporting was "flawed“ and "grossly exaggerated the number of witnesses and what they had perceived"

Perceiver centred determinants of helping personality

is there actually such a thing as altruistic personality?

Bierhoff, Klein & Kramp 1991:

•People who helped in a traffic accident vs those who did not help

•Helpers and non-helpers distinguished on:

•the norm of social responsibility

•internal locus of control

•greater dispositional empathy

Evidence is correlational and it’s not clear whether personality traits cause helping behaviour

perceiver centred determinants of helping: mood

individuals who feel good are more likely to help someone in need compared to those who feel bad

•Holloway et al., 1977: receiving good news-> increased willingness to help

•Isen (1970) found that teachers who were more successful on a task were more likely to contribute later to a school fundraising event. In fact, those who did well donated 7 times as much as others!

Though mood effects may be short-lived:

•Isen, Clark, Schwartz 1976: increased willingness to help a stranger only within the first seven minutes of positive mood induction

Perceiver centred determinants of helping: competence

Feeling competent to deal with an emergency makes it more likely that help will be given; there is the awareness that ‘I know what I am doing’ (Korte, 1971).

Specific kinds of competence have increased helping in these contexts:

People were more willing to help others move electrically charged objects if they were told they had a high tolerance for electric shocks (Midlarsky & Midlarsky, 1976);

People were more likely to help to recapture a dangerous lab rat if they were told they were good at handling rats (Schwartz & David, 1976).

Certain skills are perceived as being relevant to some emergencies, e.g., in reacting to a stranger who is bleeding, first-aid trained individuals were more likely to intervene (Shotland & Heinold, 1985).

Recipient centred determinants of prosocial behaviour: group membership

Levine et al., 2005 study 1

•45 Manchester United (ManU) fans

•Participants directed to take a short walk during which they witness an emergency incident

•Group membership is manipulated

•confederate wears Man U, Liverpool FC or plain sports top

•Rate of helping the confederate measured

•ManU fans were more likely to help other ManU fans than Liverpool FC fans or those not supporting a football team

Helping behaviour increased for in group members

Levine et al., 2005 study 2

•Same design as the first study

•Participants were told they were taking part in a study about football fans

•Focusing on the positives of being a football fan

•Measured helping behaviour to confederate who is wearing ManU, Liverpool FC, or plain top.

•Equally likely to help confederate wearing ManU or Liverpool FC top.

•those wearing a plain top were less likely to be helped.

Broadening the boundaries of social categories may increase helping behaviour

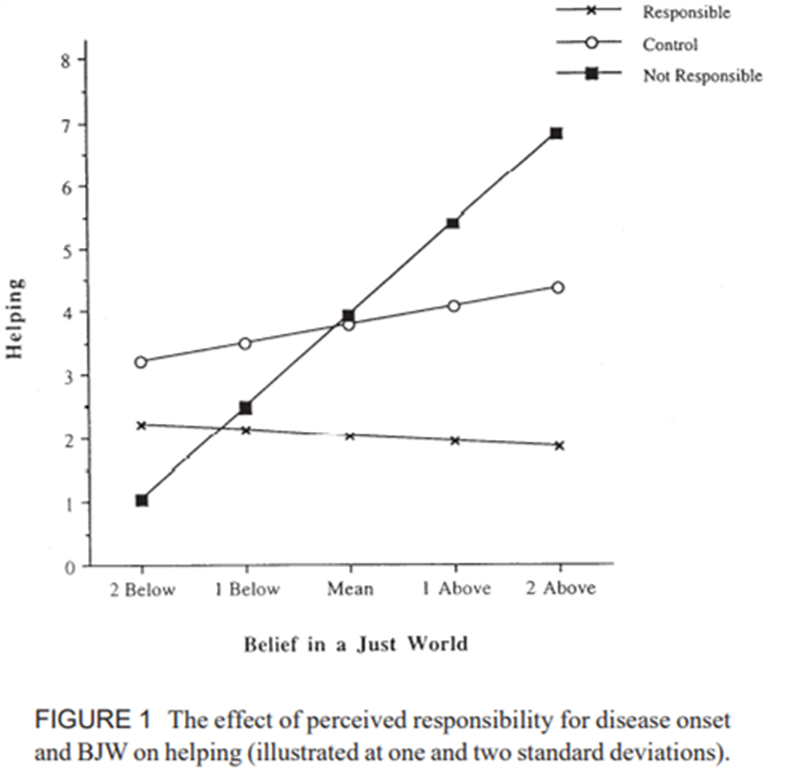

Recipient centred determinants of prosocial behaviour: responsibility for misfortune

people are generally more likely to help people who are not responsible for their misfortune (e.g. just world hypothesis)

Just world hypothesis: the world is a just and fair place and, if we come across anyone who is undeservedly suffering we help them to restore our belief in a just world.

Turner DePalma et al., 1999

•98 participants read booklet about a fictional disease

•Disease was either caused by a genetic anomality or an action of the individual or no information was given

•Measured participants’ belief in a just world

•Offered twelve helping options with differing commitment levels

•Helping behaviour was significantly increased when it was believed that the person was not responsible for illness

•People with high belief in a just world helped more only when the person was believed not to be responsible for their illness.

Receiving help

We have been focusing on the helper but what about the recipient. Do they always want help?

Wakefield, Hopkins, and Greenwood (2012)

•Female students were made aware that women may be stereotyped by men as dependant, and were then placed in a situation where they needed help;

•Asked to solve a set of anagrams

•Those made aware of the dependency stereotype (compared to controls who were not) were less willing to seek help;

•Those that did seek help felt worse the more help they sought.

Receiving help can be interpreted negatively if it confirms a negative stereotype about the recipient

READING (518-524, 526-537, 540 (competence), 546 (to motives & goals)

Prosocial behaviour:

Lauren Wispé (1972) defined prosocial behaviour as behaviour that has positive social consequences and contributes to the physical or psychological well-being of another person.

It is voluntary and is intended to benefit others (Eisenberg, Fabes, Karbon, Murphy, Wosinski, Polazzi, et al., 1996).

Being prosocial includes both being helpful and altruistic. It also includes acts of charity, cooperation, friendship, rescue, sacrifice, sharing, sympathy and trust. What is considered prosocial is defined by society’s norms.

Helping behaviour

Helping behaviour is a subcategory of prosocial behaviour. Helping is intentional, and it benefits another living being or group.

If you accidentally drop a ten-pound note and someone finds it and spends it, you have not performed a helping behaviour. But if you gave ten pounds to Connie who really needed it, you have helped her.

On the other hand, making a large public donation to a charity because you wanted to appear generous is not helping behaviour. Some corporate donations to a good cause may be driven by product promotion; e.g. in pursuit of a long-term increase in profit.

Helping can even be antisocial; e.g. overhelping, when giving help is designed to make others look inferior

Altruism

Altruism is another subcategory of prosocial behaviour. It refers to an act that is meant to benefit another person rather than oneself.

True altruism should be selfless, but it can be difficult to prove true selflessness (Batson, 1991). For example, can we ever really know that an act does not stem from a long-term ulterior motive, such as ingratiation?

Ervin Staub (1977) noted that there are sometimes ‘private’ rewards associated with acting prosocially, such as feeling good or being virtuous. There is a considerable debate over how magnanimous human nature really is

Why and when people help

biology and evolution

Evolutionary biologists have grappled with these and other instances of cooperation in the animal world. Jeffrey Stevens and his colleagues (Stevens, Cushman, & Hauser, 2005) have distinguished two reliable explanations of cooperative behaviour in animals and humans:

mutualism- cooperative behaviour benefits the cooperator as well as others; a defector will do worse than a cooperator

kin selection- those who cooperate are biased towards blood relatives because it helps propagate their own genes; the lack of direct benefit to the cooperator indicates altruism

what is an obvious candidate for the evolutionary account of human altruism?

kin selection:

Eugene Burnstein and his colleagues studied ‘decision rules’ for being altruistic that might reflect genetic overlap between persons. Participants, who rated how likely they would be to help others in several situations, favoured the sick over the healthy in everyday situations but favoured the healthy over the sick in life-or-death situations. They took more account of kinship in everyday situations and the healthy in life-or-death situations. Finally, people were more likely to assist the very young or the very old in everyday situations, but under famine conditions, people prefer to help 10-year-olds or 18-year-olds rather than infants or older people. These data are consistent with the idea that close kin will get crucial help when ‘the chips are down’.

the idea that we’re wired to help others as well as kin has generated a debate

for example, between psychologists and sociobiologists (Vine, 1983). Few social psychologists accept an exclusively evolutionary explanation of human prosocial behaviour, and they accept evolutionary explanations only to a limited extent. The philosopher Derek Turner asked the question, ‘Is altruism an anomaly?’ We can ask psychological questions about people’s motives for helping others and philosophical questions also about moral obligations to do so. We can also ask biological questions about what we have inherited, but one concept is a sticking point – fitness altruism : ‘How could natural selection ever smile upon organisms that sacrifice their own reproductive fitness for another’s benefit?’

If I adopt a child who is not kin, is that a strong case for fitness altruism? If so, what are its genetic mechanisms and how did they evolve? A problem with evolutionary theory as a sole explanation of altruism is the lack of convincing human evidence. For example, a case such as the failure to help Kitty Genovese is difficult to explain at a biological level. Another criticism is the scant attention afforded by evolutionary theorists to the work of social learning theorists, in particular to the role of modelling

A problem with evolutionary theory as a sole explanation of altruism is the lack of convincing human evidence. For example, a case such as the failure to help Kitty Genovese is difficult to explain at a biological level. Another criticism is the scant attention afforded by evolutionary theorists to the work of social learning theorists, in particular to the role of modelling

Empathy and arousal

A common experience before acting prosocially is a state of arousal followed by empathy. Empathy is an emotional response to someone else’s distress, a reaction to witnessing a disturbing event. Adults and children respond empathically to signs that a person is troubled, which implies that watching someone suffer is unpleasant.

Have you ever looked away when a film shows someone being tortured? Censors forewarn us if a film depicts scenes of violence, and most of us have been in an audience when a few tears are not far away. Even infants one or two days old can respond to the distress of another infant. In real life, people often fail to act prosocially because they are actively engaged in avoiding empathy

however, when we try to help are we just trying to reduce our own discomfort?

The extra ingredient is empathy, an ability to identify with someone else’s experiences, particularly their feelings (Krebs, 1975). Empathy is related to perspective taking, being able to see the world through others’ eyes, but it is not the same thing. Generally speaking, empathy is affectand feeling-based (I feel your pain), whereas perspective taking is cognitionbased (I see your pain)

calculating whether to help

The bystander-calculus model of helping involves body and mind, a mixture of physiological processes and cognitive processes. According to sociologist Jane Piliavin, when we think someone is in trouble, we work our way through three stages or sets of calculations before we respond.

First, we are physiologically aroused by another’s distress.

Second, we label this arousal as an emotion.

Third, we evaluate the consequences of helping.

Interestingly, not helping can also involve costs. Piliavin distinguished between empathy costs of not helping and personal costs of not helping . A critical factor is the relationship between the bystander and the victim. We have already seen that empathic concern is one motive for helping a distressed person; conversely, not helping when you feel empathic concern results in empathy costs (e.g. anxiety) in response to the other’s plight. Thus, the clarity of the emergency, its severity and the closeness of the bystander to the victim will increase the costs of not helping

personal costs of not helping

self-blame

public censure

certain characteristics of the person in distress,

for instance, the greater the victim’s need for help, the greater the costs of not helping. If you believe a victim might die if you do not help, the personal costs are likely to be high.

If a tramp in the street asked you for money to buy alcohol, the personal costs of refusing might not be high; but if the request was for money for food or medicine, the costs might be quite high.

what increases the likelihood of a bystander helping?

the more similar the victim is to the bystander, the more likely the bystander is to help. Similarity causes greater physiological arousal in bystanders and thus greater empathy costs of not helping. Similar victims may also be friends, for whom the costs of not helping would be high.

What does the bystander-calculus model the Genovese case?

The bystander-calculus model suggests that, although the onlookers would have been aroused and felt personal distress and empathic concern, the empathy costs and personal costs were not sufficient. Personal costs, in particular, may have deterred people from intervening. What if they got killed themselves? The costs of not helping could be either high or low, depending on how people interpreted the situation: for example, was it merely a heated marital spat? Situational influences are significantly involved when adults decide whether to help in an emergency

Learning to be helpful

A different explanation of helping is that prosocial behaviour is intricately bound with becoming socialised: it is learned, not innate. The processes of classical conditioning, instrumental conditioning and observational learning all contribute to being prosocial. This learning theory perspective on prosocial behaviour has recently been pursued particularly strongly within developmental and educational psychology – for example, there is research showing how prosocial behaviour is acquired in childhood

Childhood is a critical period for learning. Carolyn Zahn-Waxler has studied the development of emotions in children, concluding that how we respond to distress in others is connected to the way we learn to share, help and provide comfort, and that these patterns emerge between the ages of 1 and 2

giving instructions: Joan Grusec found that simply telling children to be helpful to others actually works. Telling a child what is appropriate establishes an expectation and a later guide for action. However, preaching about being good is of doubtful value unless a fairly strong form is used. Furthermore, telling children to be generous if the ‘preacher’ behaves inconsistently is pointless: ‘do as I say, not as I do’ does not work. Grusec reported that when an adult acted selfishly but urged children to be generous, the children were actually less generous.

Using reinforcement: Behaviour that is rewarded is more likely to be repeated. When young children are rewarded for offering to help, they are more likely to offer help again later. Similarly, if they are not rewarded, they are less likely to offer help again

exposure to models: J. Philippe Rushton (1976) concluded that reinforcement is effective in shaping behaviour, but modelling is even more effective. Watching someone else helping another is a powerful form of learning. Take the case of young Johnny who first helps his mummy to carry some shopping into the house and then wants to help in putting it away, and then cleans up his bedroom.

In older studies of the effect of viewing prosocial behaviour on television, the general finding has been that children’s attitudes towards prosocial behaviour are improved. However, the effect on prosocial behaviour was weak and even weaker as time passed. Children who behave prosocially are also able to tolerate a delay in gratification and are more popular with their peers. There are also close developmental links between prosocial skills, coping and social competence, which suggests an overall socialisation process into adulthood. We can take some comfort that it is never too late – adults can also be influenced by a helpful model.

When a person observes a model and behaves in kind, is this just matter of mechanical imitation?

Bandura says NO! according to SLT, it is the knowledge of what happens to the model that determines whether or not the observer will help. As with direct learning, a positive outcome increases a model’s effectiveness in influencing the observer to help, while a negative outcome decreases the model’s effectiveness.

Harvey Hornstein (1970) conducted an experiment where people observed a model returning a lost wallet. The model either appeared pleased to be able to help, appeared displeased at the bother of having to help or showed no strong reaction. Later, the participant came across another ‘lost’ wallet. Those who had observed the pleasant consequences helped the most; those who observed the unpleasant consequences helped the least. Observing the outcomes for another person is called learning by vicarious experience; it can increase the prevalence of both selfish and selfless behaviour

Game player and the media

Lawrence Rosenkoetter (1999) found that children who watched television comedies that included a moral lesson engaged more frequently in prosocial behaviour than children who did not, provided they understood the principle involved. Gentile and his colleagues investigated the effects of playing video games featuring prosocial acts on prosocial behaviour measured by questionnaires

In a series of three developmental studies, three age groups of Singaporeans, Americans and Japanese played a variety of both prosocial and violent video games. A central finding was that when the video content was prosocial, the participants acted in more helpful ways, but when it was violent, they acted in more hurtful ways. These effects were consistent across cultures and age groups.

The effects of the media can be broadened to include music.

For example, Tobias Greitmeyer (2009) found that both German and British participants who listened to prosocial songs were more willing to offer help to other people, without request. Greitmeyer and Osswald (2010) have reported that viewing prosocial videos increased the rate of helping behaviour; and further, these videos made prosocial cognitions more accessible. Consequently, they argued that the General Aggression Model (GAM) could be developed into a General Learning Model (GLM)

The impact of attribution

People make causal attributions for helping. To continue being helpful on more than one occasion requires a person to internalise the idea of ‘being helpful’. Helpfulness can then be a guide in the future when helping is an option. A self-attribution can be even more powerful than reinforcement for learning helping behaviour: young children who were told they were ‘helpful people’ donated more tokens to a needy child than those who were reinforced with verbal praise, and this effect persisted over time. Indeed, Perry and his colleagues found that children may feel bad and experience self-criticism when they fail to live up to the standards implied by their own attributions

If we are wondering whether to offer help to someone in need, we usually try to figure out who or what this person might be. Sometimes we may even blame an innocent victim for their plight. One reason why we might do this is to make the world seem like a just place where bad things happen to bad people and good things to good people – the just-world hypothesis. People are responsible for their own plight and get what they deserve, and since we tend to assume that we are good people, we can then breathe a sigh of relief that nothing bad will happen to us.

Therefore, if some victims deserve their fate, we can think ‘Good, they had that coming to them!’ and not help them. Some witnesses in the Kitty Genovese case may have believed that it was her fault for being out so late – a familiar response to many crimes. Take another rather disturbing example: perhaps a rape victim ‘deserved’ what happened because her clothing was too tight or revealing? Accepting that the world must necessarily be a just place begins in childhood and is a learnt attribution.

. A necessary precondition of actually helping is to believe that the help will be effective. Miller (1977) isolated two factors that can convince a would-be helper: (1) the victim is a special case rather than one of many, and (2) the need is temporary rather than persisting. Each of these allows us to decide that giving aid ‘right now’ will be effective. Invoking this line of reasoning, Peter Warren and Iain Walker (1991) showed that if the needs of a person in distress can be specified, others can use this information to determine if giving help is justified. In a field study of more than 2,500 recipients, a letter mail-out solicited donations for a refugee family from Sudan. Cover letters with slightly different wording were used. More donations were recorded when the letter highlighted that: (1) the donation was restricted to this particular family rather than being extended to other people in Sudan; and (2) the family’s need was only short term. In short, the case was just and action would be effective.

the bystander effect:

Latane and Darley’s cognitive model

Stemming directly from the wide public discussion and concern about the Genovese case, Bibb Latané and John Darley began a programme of research. Surely, these researchers asked, empathy for another’s suffering, or at the very least a sense of civic responsibility, should lead to an intervention in a situation of danger? Furthermore, where several bystanders are present, there should be a correspondingly greater probability that someone will help. Consider first the elements of an emergency situation:

it can involve danger, for person or property

it is an unusual event, rarely encountered by the ordinary person

it can differ widely in nature, from a bank on fire to a pedestrian being mugged

it is not foreseen, so that prior planning of how to cope is improbable

it requires instant action, so that leisurely consideration of options is not feasible

Latané and Darley noted that it would be easy simply to label the failure to help a victim in an emergency as apathy – an uncaring response to the problems of others. However, they reasoned that the apparent lack of concern shown by the witnesses in the Genovese case could conceal other processes. An early finding was that failure to help occurred more often when the size of the group of witnesses increased. Latané and Darley’s cognitive model of bystander intervention proposes that whether a person helps depends on the outcomes of a series of decisions. At any point along this path, a decision could be made that would terminate helping behaviour.

Latané and Darley suggested that the presence of others can inhibit people from responding to an emergency: the more people, the slower the response (‘he’s having a fit’ study). Even worse, many of the people who did not respond were persuaded that if others were passive, there was no emergency. Some later reported that there was no danger from the smoke. In a real emergency, this could easily have proved fatal.

Processes contributing to bystander apathy

is the individual aware that others are present?

can the individual actually see or hear the others and be aware of how they are reacting?

can these others monitor the behaviour of the individual?

diffusion of responsibility

Think back to social loafing, where a person who is part of a group often offloads responsibility for action to others. In the case of an emergency, the presence of other onlookers provides the opportunity to transfer responsibility for acting, or not acting, to them. The communication channel does not imply that the individual can be seen by the others or can see them. It is necessary only that they be available, somewhere, for action. People who are alone are most likely to help a victim because they believe they carry the entire responsibility for action. If they do not act, nobody else will. Ironically, the presence of just one other witness allows diffusion of responsibility to operate among all present.

Audience inhibition: Other onlookers can make people self-conscious about taking action; people do not want to appear foolish by overreacting. In the context of prosocial behaviour, this process is sometimes referred to as a fear of social blunders . Have you felt a dread of being laughed at for misunderstanding little crises involving others? What if it is not as it seems? What if someone is playing a joke? The communication channel implies that the others can see or hear the individual, but it is not necessary that they can be seen

social influence: Other onlookers provide a model for action. If they are passive and unworried, the situation may seem less serious. The communication channel implies that the individual can see the others, but not vice versa.

The three-in-one experiment

By the use of TV monitors and cameras, participants were induced to believe that they were in one of four conditions with respect to other onlookers. They could (1) see and be seen; (2) see, but not be seen; (3) not see, but be seen; or (4) neither see nor be seen. This complexity was necessary to allow for the consequences of sequentially adding social influence and audience inhibition effects to that of diffusion of responsibility. We should note here that diffusion of responsibility must always be involved if a bystander is, or is thought to be, present at the moment of the emergency. However, the additive effect of another process can be assessed and then compared with the effect of diffusion acting on its own.

Limits to the bystander effect

Bystanders who are strangers to each other inhibit helping even more because communication between them is slower. When bystanders are known to each other, there is much less inhibition of prosocial behaviour than in a group of strangers (Latané & Rodin, 1969; Rutkowski, Gruder, & Romer, 1983). However, Jody Gottlieb and Charles Carver (1980) showed that even among strangers, inhibition is reduced if they know that there will be an opportunity to interact later and possibly explain their actions. Overall, the bystander effect is strongest when the bystanders are anonymous strangers who do not expect to meet one another again, which was most likely the situation in the Genovese case. Catherine Christy and Harrison Voigt (1994) found that bystander apathy is reduced if the victim is an acquaintance, friend or relative or is a child being abused in public

the studies above have much in common: bystanders who are strangers and who are present by chance at an emergency generally do not constitute a group- friends do

For example, if the victim is female and the bystanders are male, gender becomes a salient category, males are now a group, and the sex-role stereotype of the chivalrous male can ‘spring into action’ (Levine & Crowther, 2008). The key point is that normative expectations about how to respond in a particular situation come into play if a social identity is primed by the context. In the absence of a salient identity to guide appropriate action, people are very much on their own to figure out what to do

the influence of Mood states:

Good mood:

Alice Isen

found that teachers who were more successful on a task were more likely to contribute later to a school fundraising drive. Those who had done well in fact donated seven times as much as the others! So, such momentary feelings as success on a relatively innocuous task can dramatically affect prosocial behaviour. Isen suggested that doing well creates a ‘warm glow of success’, which makes people more likely to help.

People who hear good news on the radio express greater attraction towards strangers and greater willingness to help than people who hear bad news, and people are in better moods and are more helpful on sunny, temperate days than on overcast, cold days. Even experiences such as reading aloud statements expressing elation, or recalling pleasant events from our childhood, can increase the rate of helping. The evidence consistently demonstrates that good moods produce helpful behaviour under a variety of circumstances.

Bad mood

They concentrate on themselves, their problems and worries (Berkowitz, 1970), are less concerned with the welfare of others and help others less (Weyant, 1978). Berkowitz (1972b) showed that self-concern lowered the rate and amount of helping among students awaiting the outcome of an important exam.

Darley and Batson (1973) led seminary students, who were due to give a speech, to think they were quite late, just in time or early. They then had the opportunity to help a man who had apparently collapsed in an alley. The percentages that helped were: quite late, 10 per cent; just in time, 45 per cent; and early, 63 per cent.

Competence: ‘have skills, will help’

Feeling competent to deal with an emergency makes it more likely that help will be given; there is the awareness that ‘I know what I’m doing

specific kinds of competence have increased helping in these contexts:

People who were told they had a high tolerance for electric shock were more willing to help others move electrically charged objects.

People who were told they were good at handling rats were more likely to help to recapture a ‘dangerous’ laboratory rat.

The competence effect may even generalise. Kazdin and Bryan (1971) found that people who thought they had done well on a health examination or even on a creativity task were later more willing to donate blood.

Pantin and Carver (1982) made student participants feel more competent by showing them a series of films on first aid and emergencies. Three weeks later, they had the chance to help a confederate who was apparently choking. The bystander effect was weakened by having previously seen the films. Pantin and Carver also reported that the increase in helping persisted over time. This area of skill development is at the core of Red Cross first-aid training courses for ordinary people in many countries.

The impact of skill level was tested experimentally by comparing professional help with novice help (Cramer, McMaster, Bartell, & Dragna, 1988). Participants were two groups of students, one highly competent (registered nurses) and the other less competent (general students). In a contrived context, each participant waited in the company of a non-helping confederate. The nurses were more likely than the general students to help a workman, seen earlier, who had apparently fallen off a ladder in an adjoining corridor (a rigged accident, with pre-recorded moans). In responding to a post-experimental questionnaire, the nurses specified that they felt they had the skills to help.