Science Olympiad: Designer Genes C

1/358

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

359 Terms

Mendel’s laws of inheritance

Law of Segregation

Law of Dominance

Law of Independent Assortment

Linkage

Incomplete

Codominance

Complementation

Law of Segregation

(each parent passes one of two alleles for each gene to their offspring, and these alleles separate during gamete formation) = offspring receive a unique combination of alleles, leading to increased genetic variation within a population, and that traits can be masked or expressed depending on whether the allele is dominant or recessive

Law of Dominance

(a dominant allele can mask the effect of a recessive allele, so only the dominant trait is expressed in a heterozygous individual) = predictability of offspring traits for simple inheritance patterns, the expression of recessive traits only in homozygous individuals, and a foundational understanding of how dominant genes can mask the presence of harmful recessive ones

Law of Independent Assortment

(alleles for different genes are sorted into gametes independently of one another) = alleles for different traits are distributed into gametes independently of one another during meiosis

Linkage

the tendency for genes located close together on the same chromosome to be inherited together during meiosis, rather than assorting independently —> violates independent assortment

Incomplete

incomplete dominance is when a heterozygote’s phenotype is a blend of the two parents' traits, like a pink flower from a red and white cross, while codominance is when both parent traits are expressed simultaneously —> violates Mendel's Law of Dominance

Codominance

a genetic inheritance pattern where both alleles in a heterozygous individual are fully and separately expressed, resulting in a phenotype that displays both traits simultaneously without blending —-> violates Mendel's Law of Dominance

Complementation

when two different recessive mutations that cause the same phenotype, when combined, produce a normal phenotype —-> does not violate specific law, but leads to a modified phenotypic outcome which initially appears to be an exception to simple Mendelian inheritance patterns.

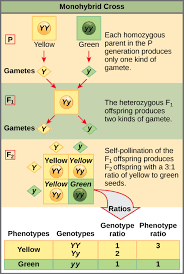

Monohybrid cross

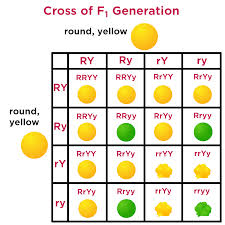

Dihybrid cross

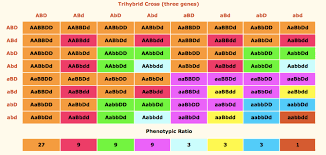

Trihybrid cross

What do hybrid cross charts do?

Predict genotypes and phenotypes of offspring and compute their likelihood based on Punnett Squares and experimental data using probability rules

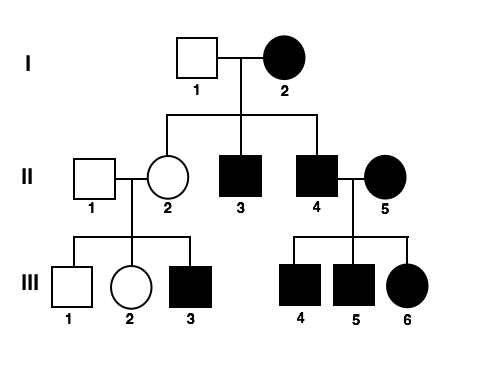

What is this and what does everything mean?

A pedigree (dominant vs. recessive traits)

Dominant = shaded

Recessive = not shaded

Male = square

Circle = female

Autosomal traits

Any chromosome that is not a s*x chromosome (X or Y)

Where does an autosomal trait appear?

With roughly equal frequency in both males and females, while a sex-linked trait (specifically X-linked) is more common in males because they have only one X chromosome and no second copy to mask a recessive allele

Female vs. male sex-linked

Yes, a female can have a sex-linked trait, but the presentation can differ from a male's. For X-linked recessive traits, a female typically needs to inherit the gene on both of her X chromosomes to be affected, whereas a male only needs one. However, if a female has the trait on one X chromosome, she is considered a carrier and can pass it to her offspring.

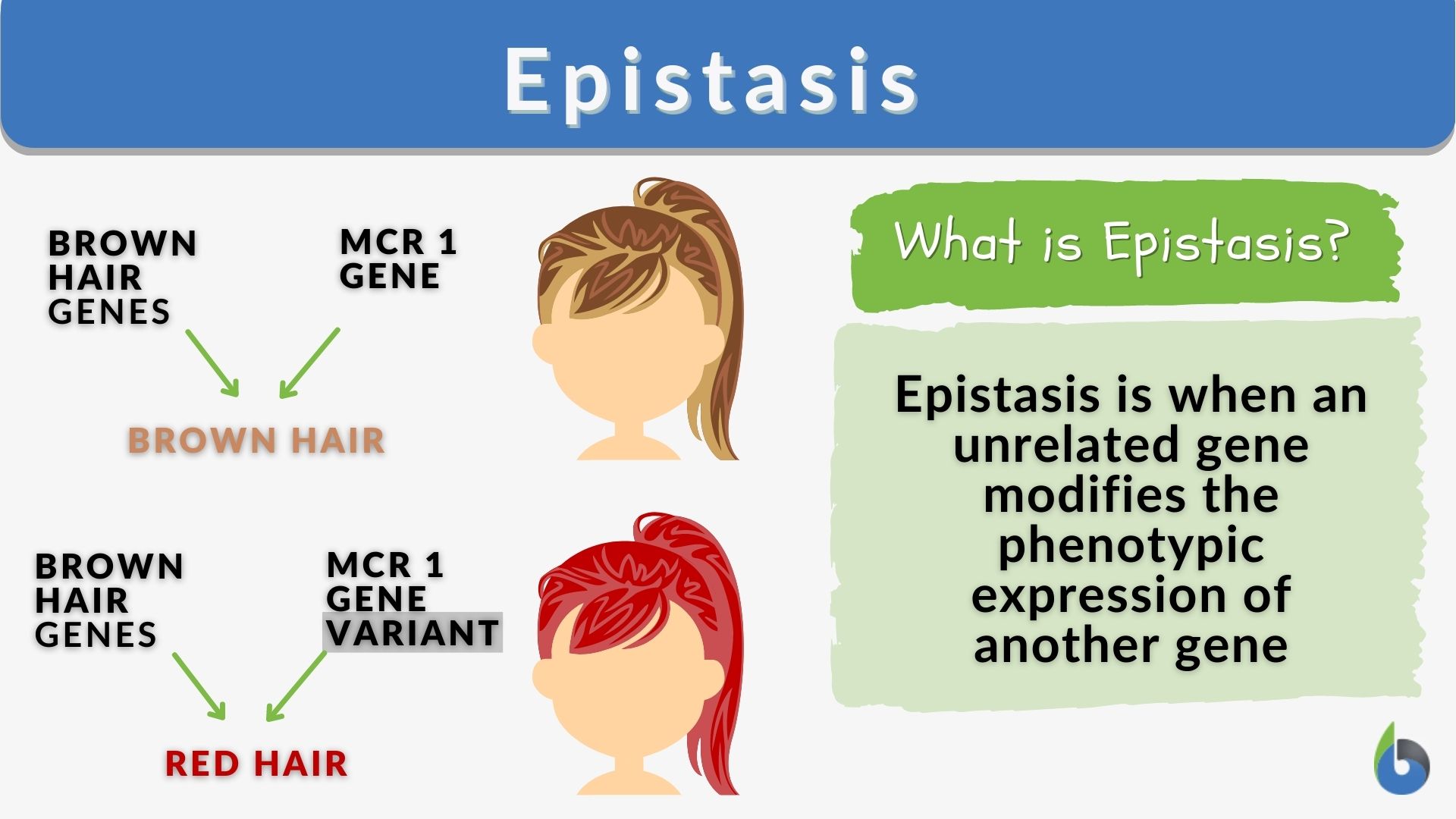

Epistasis

The interaction of genes that are not alleles, in particular the suppression of the effect of one such gene by another. Two or more genes where the expression of one gene (the epistatic gene) masks or modifies the expression of another gene (the hypostatic gene). This is used to explain how certain traits are inherited

What does this show?

Suppression of effect of one gene by another

How does Epistasis predict gene outcomes?

Epistasis predicts gene outcomes by demonstrating how one gene's alleles can mask or modify the effect of alleles at another gene locus, leading to non-Mendelian phenotypic ratios. This interaction means that the effect of a gene is not independent but is dependent on the genetic background of the other gene.

Inheritance pattern which violate Mendel’s laws of inheritance

Incomplete dominance, codominance, multiple alleles, sex-linked traits, polygenic inheritance, gene linkage, and maternal (organelle) inheritance.

Mitosis stages

Prophase

Metaphase

Anaphase

Telophase

Cytokinesis

Prophase Mitosis

Chromosomes condense and become visible; the nuclear envelope breaks down.

Metaphase mitosis

Chromosomes align at the center of the cell (the metaphase plate).

Anaphase mitosis

Sister chromatids separate and move to opposite ends of the cell.

Telophase mitosis

New nuclear envelopes form around the two sets of chromosomes, which begin to decondense.

Cytokinesis mitosis

The cell physically divides into two daughter cells, typically occurring concurrently with telophase.

Key structures of mitosis

chromosomes

Spindle fibers

Centrioles (in animal cells)

Centromere

Kinetochore

Chromosomes in mitosis

The thread-like structures carrying genetic information that become condensed and visible.

Spindle fibers in mitosis

Filaments that attach to chromosomes and pull them apart.

Centrioles (in animal cells) in mitosis

Organelles that organize the spindle fibers.

Centromere in mitosis

The region where sister chromatids are joined, and where spindle fibers attach.

Kinetochore in mitosis

Protein structures on the centromere where the microtubules bind.

Meiosis phases

Meiosis I:

Prophase I

Metaphase I

Anaphase I

Telophase I

Meiosis II:

Prophase II

Metaphase II

Anaphase II

Telophase II

Prophase I (meiosis)

Chromosomes condense, homologous chromosomes pair up (synapsis), and crossing over occurs.

Metaphase I (meiosis)

Homologous pairs align at the center of the cell.

Anaphase I (meiosis)

Homologous chromosomes separate and move to opposite poles.

Telophase I (meiosis)

Chromosomes arrive at poles, and the cell divides (cytokinesis).

Prophase II (meiosis)

Chromosomes condense again.

Metaphase II (meiosis)

Sister chromatids align at the center of the cell.

Anaphase II (meiosis)

Sister chromatids separate and move to opposite poles.

Telophase II (meiosis)

Chromatids arrive at poles, and cells divide (cytokinesis), resulting in four haploid daughter cells.

Key structures of Meiosis

Chromosomes

Homologous chromosomes

Sister chromatids

Centromere

Spindle fibers/Apparatus

Centrosomes (or Microtubule Organizing Centers)

Kinetochore

Nuclear Envelope/Membrane

Synaptonemal Complex

Chiasmata (singular: chiasma)

Chromosomes in Meiosis

Structures made of condensed chromatin that carry genetic information. They replicate before meiosis and exist as duplicated sister chromatids joined at the centromere.

Homologous chromosomes is Meiosis

Pairs of chromosomes, one from each parent, that are similar in size and gene location. They pair up during prophase I to form tetrads.

Sister chromatids in Meiosis

The two identical copies of a replicated chromosome, joined at the centromere. They separate during anaphase II.

Centromere in Meiosis

The region where sister chromatids are attached and where spindle fibers bind via the kinetochore.

Spindle Fibers/Apparatus in Meiosis

Protein structures made of microtubules that attach to chromosomes and pull them to opposite poles of the cell.

Centrosomes (or Microtubule Organizing Centers) in meiosis

Structures at the cell's poles that organize the formation of the spindle fibers.

Kinetochore in meiosis

A protein complex on the centromere to which spindle fibers attach.

Nuclear Envelope/Membrane in meiosis

The membrane that encloses the nucleus. It breaks down during prophase I and II and reforms during telophase I and II.

Synaptonemal Complex in meiosis

A protein lattice that forms during prophase I to mediate and maintain the stable pairing (synapsis) of homologous chromosomes.

Chiasmata (singular: chiasma) in meiosis

The physical points of connection between homologous chromosomes where crossing over (genetic exchange) has occurred.

Nondisjunction

the failure of homologous chromosomes or sister chromatids to separate properly during cell division (meiosis or mitosis). This error leads to daughter cells or gametes with an abnormal number of chromosomes, a condition known as aneuploidy.

Effects of nondisjunction

Pregnancy loss

Genetic disorders

Autosomal trisomies

Sex-chromosome abnormalities

Cancer risk

Pregnancy loss in nondisjunction

Most aneuploid embryos are inviable and result in spontaneous abortions or miscarriages, making nondisjunction the leading known cause of fetal loss.

Genetic disorders in nondisjunction

In cases where the offspring survives, they often have severe physical abnormalities, intellectual disabilities, and specific syndromes.

Autosomal trisomies in nondisjunction

Down syndrome

Edwards syndrome

Patau syndrome

Down syndrome

Trisomy 21

Intellectual disability, distinctive facial features, congenital heart defects.

Edwards Syndrome

Trisomy 18

Severe developmental issues, multiple organ defects; life expectancy is normally less than one year.

Patau syndrome

Trisomy 13

Severe brain, eye, and circulatory defects; life expectancy is typically a few months.

Sex chromosome abnormalities

Turner syndrome (Monosomy X, or XO)

Klinefelter syndrome (XXY)

Triple X syndrome (XXX) and XYY syndrome

Turner sydrome

Monosomy X, or XO

Short stature, webbed neck, ovarian dysgenesis, and infertility (the only survivable monosomy).

Klinefelter sydrome

XXXY

Tall stature, developmental delays, and sterility.

Triple X syndrome

XXX and XYY syndrome

Often phenotypically normal, with some potential for increased height or learning difficulties.

Cancer risk in nondisjunction

When nondisjunction occurs during mitosis in a developing organism or mature individual, it causes somatic mosaicism and can contribute to the development of certain cancers.

Somatic mosaicism

The presence of two or more genetically distinct cell populations within one individual, arising from a mutation in a single somatic (non-reproductive) cell after fertilization.

How to detect chromosomal abnormalities from karyotypes

Involve identifying both numerical abnormalities (like extra or missing chromosomes, known as aneuploidy) and structural abnormalities (such as translocations, deletions, inversions, and duplications)

How to detect chromosomal abnormalities from karyotypes (types)

Translocation

Deletion

Inversion

Duplication

Translocation

a genetic change where a piece of one chromosome breaks off and attaches to another chromosome

Deletion

the loss of a segment of genetic material from a chromosome

Inversion

a structural rearrangement where a segment of a chromosome breaks off, rotates 180 degrees, and reattaches in its original position but in reverse orientation

Duplication

a specific type of chromosomal structural mutation where a segment of a chromosome is repeated.

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium

A principle in population genetics that states that allele and genotype frequencies in a population will remain constant from generation to generation in the absence of evolutionary influences. It is based on five conditions: no mutation, random mating, no gene flow, a large population size, and no natural selection.

The consequences of violating these assumptions of the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium

Violating the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium means a population is not in genetic equilibrium, which can be caused by forces like natural selection, mutation, genetic drift, and non-random mating. Specific consequences include changes in allele and genotype frequencies (evolution), increased homozygosity, and the potential for deleterious traits to become more or less common.

Consequences of specific violations of the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium

Non-random mating

Inbreeding

Assortative mating

Overdominance

Underdominance

Directional selection

Genetic drift

Mutation

Gene flow/Migration

Non-random mating

Changes in genotype frequencies without changing allele frequencies.

Inbreeding

Increases homozygosity, making individuals more likely to be homozygous for both beneficial and harmful recessive alleles, which can lead to an increased incidence of genetic disorders.

Assortative mating

Leads to an excess of homozygotes compared to what is expected by chance.

Natural selection

Modifies allele and genotype frequencies based on fitness.

Overdominance (heterozygote advantage) of natural selection

Results in an excess of heterozygotes.

Underdominance (heterozygote disadvantage) of natural selection

Leads to an excess of homozygotes.

Directional selection of natural selection

Causes a significant shift in allele frequencies, such as when a lethal recessive allele is selected against, although the rate of removal slows as the allele becomes rarer and is protected in heterozygotes.

Genetic drift

The random change in allele frequencies from one generation to the next, with significant effects in small populations.

Mutation

The introduction of new alleles into the population, which can alter allele frequencies.

Gene flow/Migration

Introduces new alleles from another population, changing allele frequencies.

How these consequences of natural selection are used

Indicating evolution

Understanding evolutionary forces

Informing public health

Indicating evolution

Deviations from the expected Hardy-Weinberg proportions are a sign that a population is evolving.

Understanding evolutionary forces

By observing the specific type of deviation, researchers can infer which evolutionary forces are at play, such as identifying if selection is favoring certain traits or if genetic drift is a factor.

Informing public health

Deviations from equilibrium in a population can provide insights into the genetic basis of diseases and guide public health decisions.

P + q = 1 (explanation)

P and q are the frequencies of the dominant and recessive alleles

What does P + q = 1 calculate

The allele frequencies in a population

p^2 + 2pq + q^2 = 1 (explanation)

p^2 is the frequency of the homozygous dominant genotype, 2pq is the frequency of the heterozygous genotype, and q^2 is the frequency of the homozygous recessive genotype

What does p^2 + 2pq + q^2 = 1 calculate?

The genotype frequencies in a population

Allele

one of two or more alternative forms of a gene that arise by mutation and are found at the same place on a chromosome.

Genotype

the genetic constitution of an individual organism

Central dogma of molecular biology

DNA is transcribed into RNA, which is then translated into protein. It establishes that DNA holds the instructions, RNA acts as the messenger, and proteins are the functional products.

Central dogma of reverse trascription

Reverses the traditional DNA-to-RNA flow, demonstrating that genetic information can transfer from RNA back to DNA. Enabled by the enzyme reverse transcriptase (often in retroviruses like HIV), this process synthesizes complementary DNA (cDNA) from an RNA template, which then integrates into the host genome.

Reverse transcription

The process in cells by which an enzyme makes a copy of DNA from RNA. The enzyme that makes the DNA copy is called reverse transcriptase and is found in retroviruses, such as the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Reverse transcription can also be carried out in the laboratory.

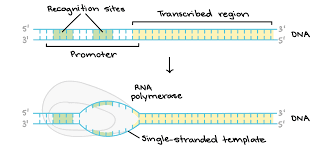

Initiation (stage of transcription)

the first, tightly regulated step of gene expression where RNA polymerase (RNAP) binds to a gene's promoter region, unwinds the DNA, and begins synthesizing RNA. It involves the assembly of a pre-initiation complex (PIC) and is divided into three key steps: closed complex formation, open complex (bubble) formation, and abortive initiation.

What does this show?

Initiation (stage of transcription)