Islamic Art & Architecture 2nd Half (Images)

1/52

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

53 Terms

Aleppo Citadel, Aleppo, Syria, 1180s

Built by Ayyubids

Largest and one of the oldest fortified castles of the west

Entrance had 6 right turns

One of the gates into the citadel, showing a muqarnas archway and ablaq stonework – alternating colored courses, with joggled voussoirs (stones that go around an arch) around the portal

Fortified gate and bridge over moat resemble Roman aqueducts

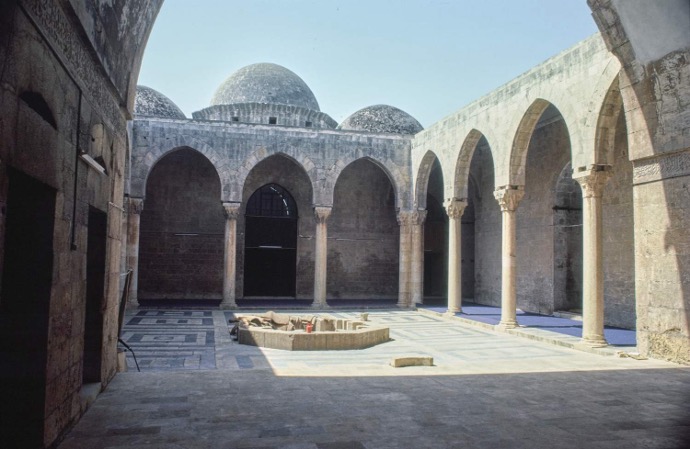

Madrasa al-Firadaus, Aleppo, Syria, 1235-41

Founded by a woman

Special place in terms of its spiritual aura

Courtyard is very geometrically thought out

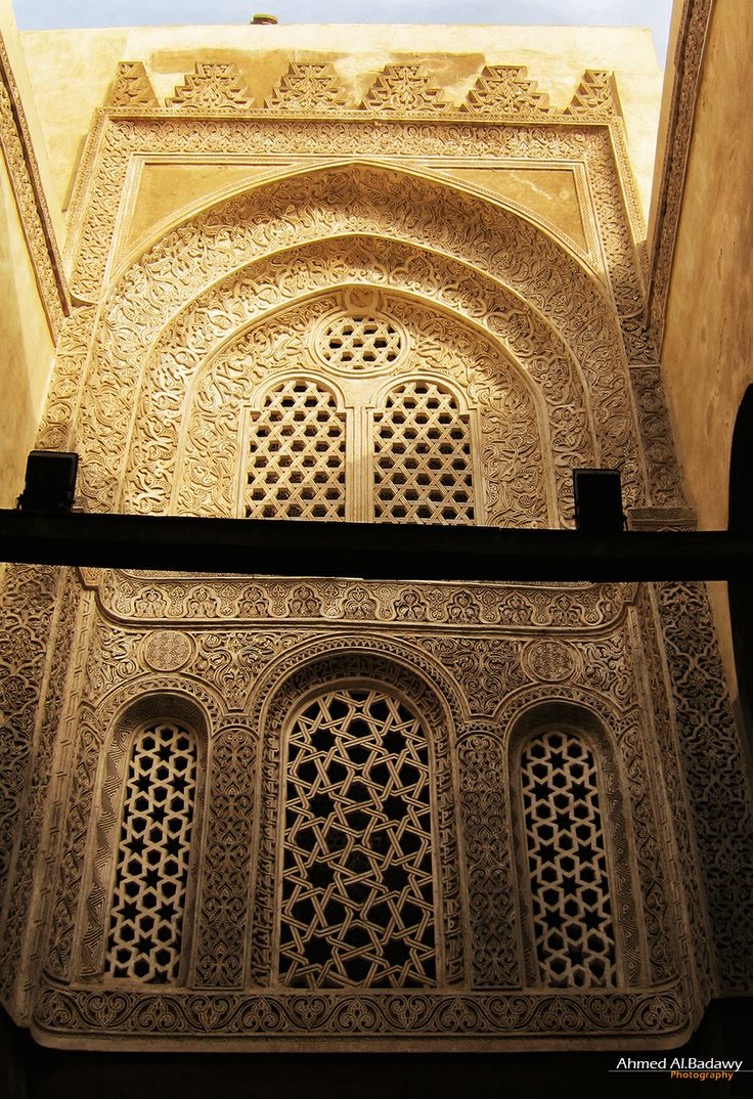

The mihrab niche in the mosque at al-Firdaus

Extraordinary stone inlay

Mamluks loved to do poly-hued interlaced stone inlay

Mausoleum of Qalawun, Cairo, Egypt, 1284-85

Entrance to the Mausoleum: mosaic, carved stucco, wooden detail, etc.

(Funeral complex of one of the first Mamluk sultans)

Similar architecture to the west

Stonework in the Mausoleum of Qala’un, Cairo (1284-85) – first use of polychrome marble inlay in Mamluk architecture

Mihrab in the mausoleum – has spolia columns, uses joggled voussoirs and glass mosaic

Palace of Bashtak, Cairo, Egypt, 1334-39

Two storied reception hall with gallery on second level for the women

Pierced wooden window grills to screen the women from the men

Upper floor windows like these helped circulate air and cool the palace (working with fountains and pools inside)

Sultan Hasan Mosque Complex, Cairo, Egypt, 1356-62

Use of the 4-Iwan plan for the madrasa – coming from Syria and Iran

Monumental entrance to the complex with muqarnas arch

Mausoleum of Sultan Qaitbai, Cairo, Egypt, 1472-74

Detail of the ornament on the dome – a perfect blend of geometry and arabesques

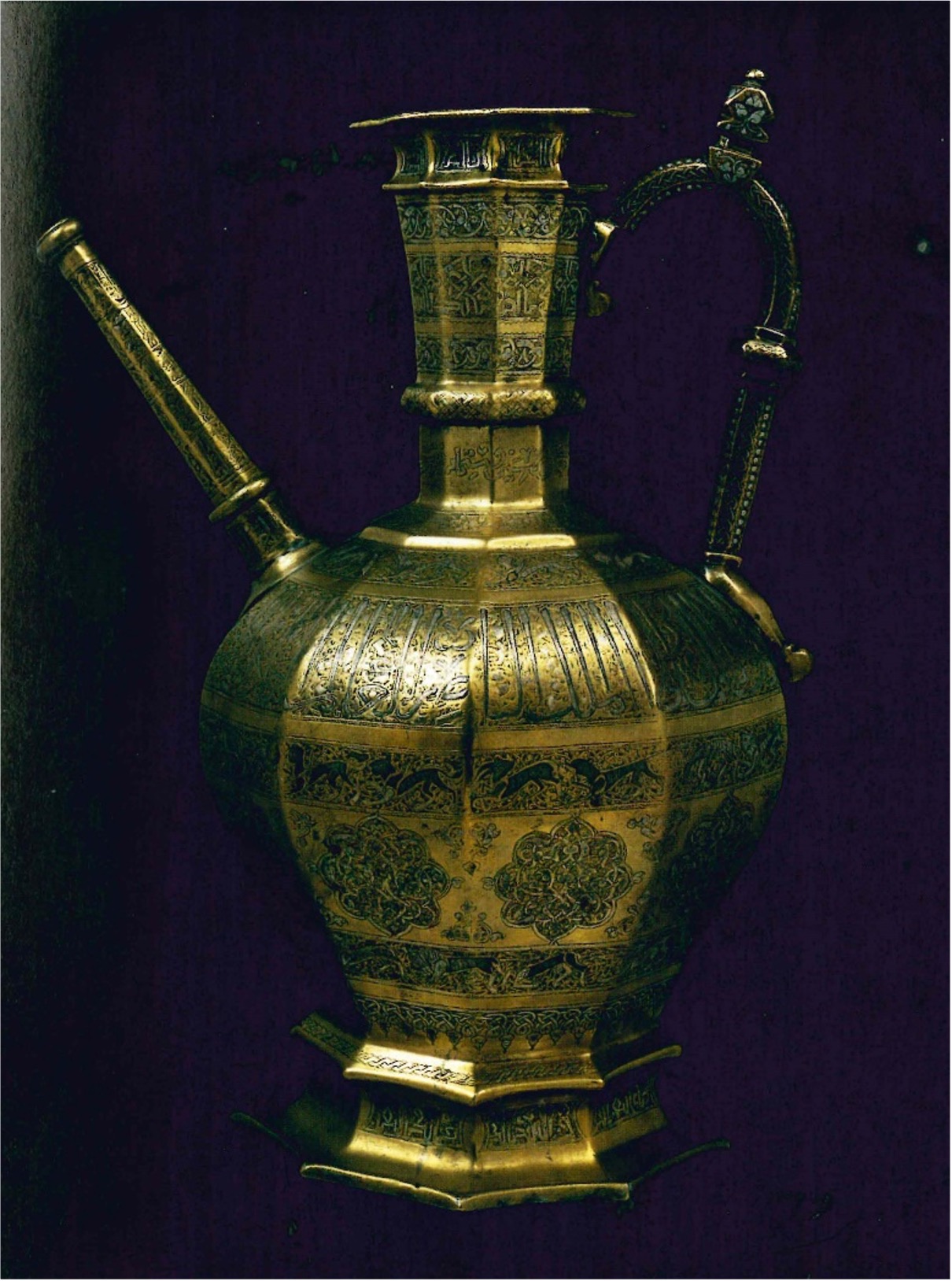

Husain ibn Muhamad, Water Ewer, Damascus, Syria, 1259

Glass Goblet, Aleppo, Syria, late 13th century

Used enameling

Steel Mirror, Syria, c. 1330

Utilized damascene work

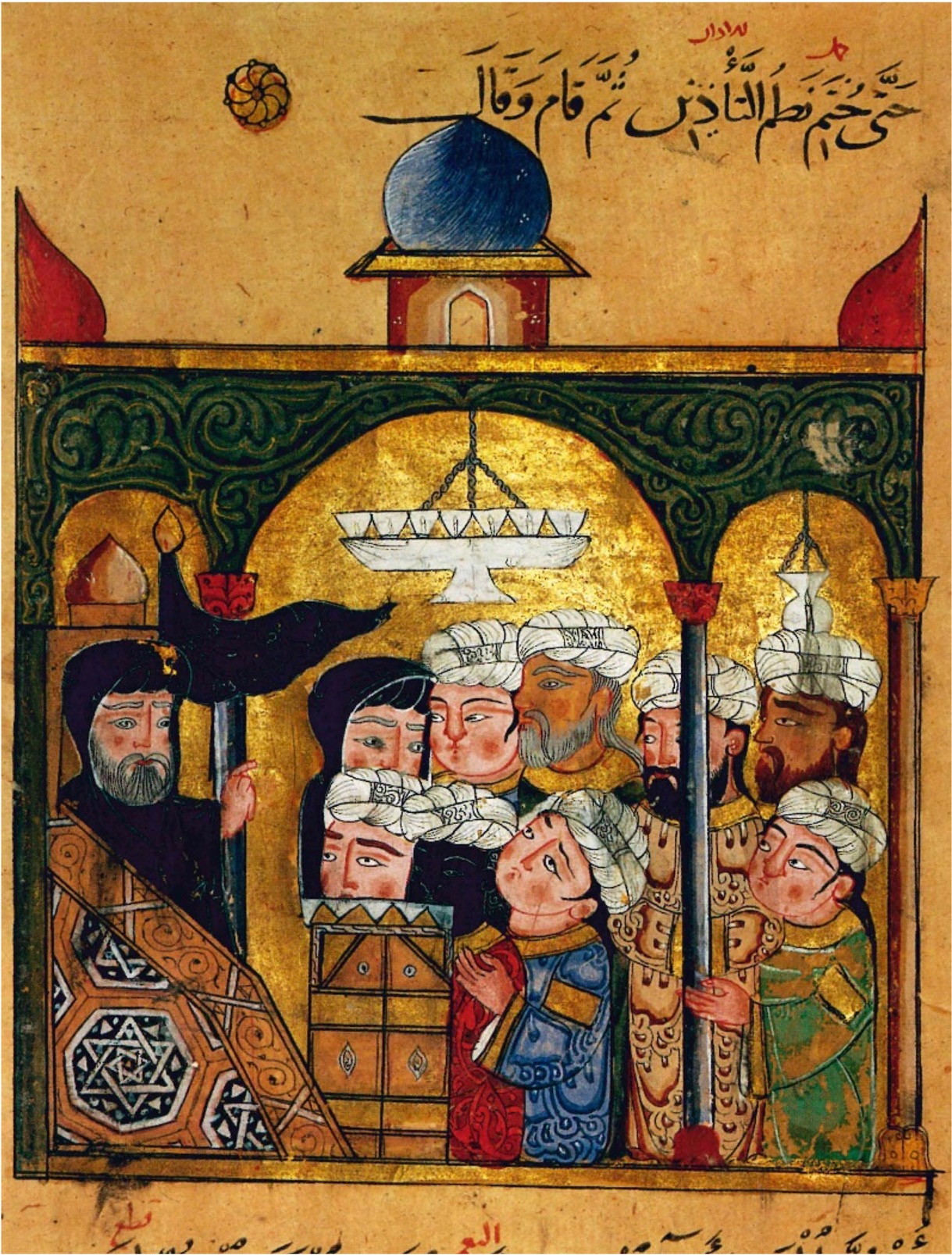

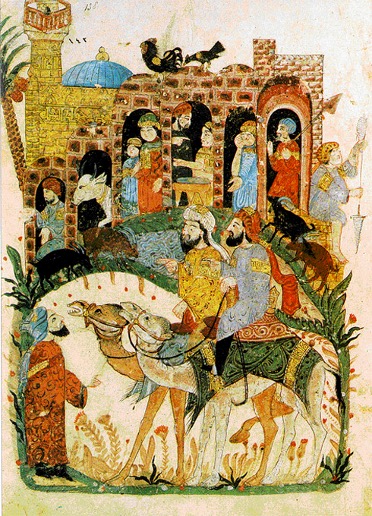

Page from Harari’s Maqamat, Cairo, Egypt, 1334

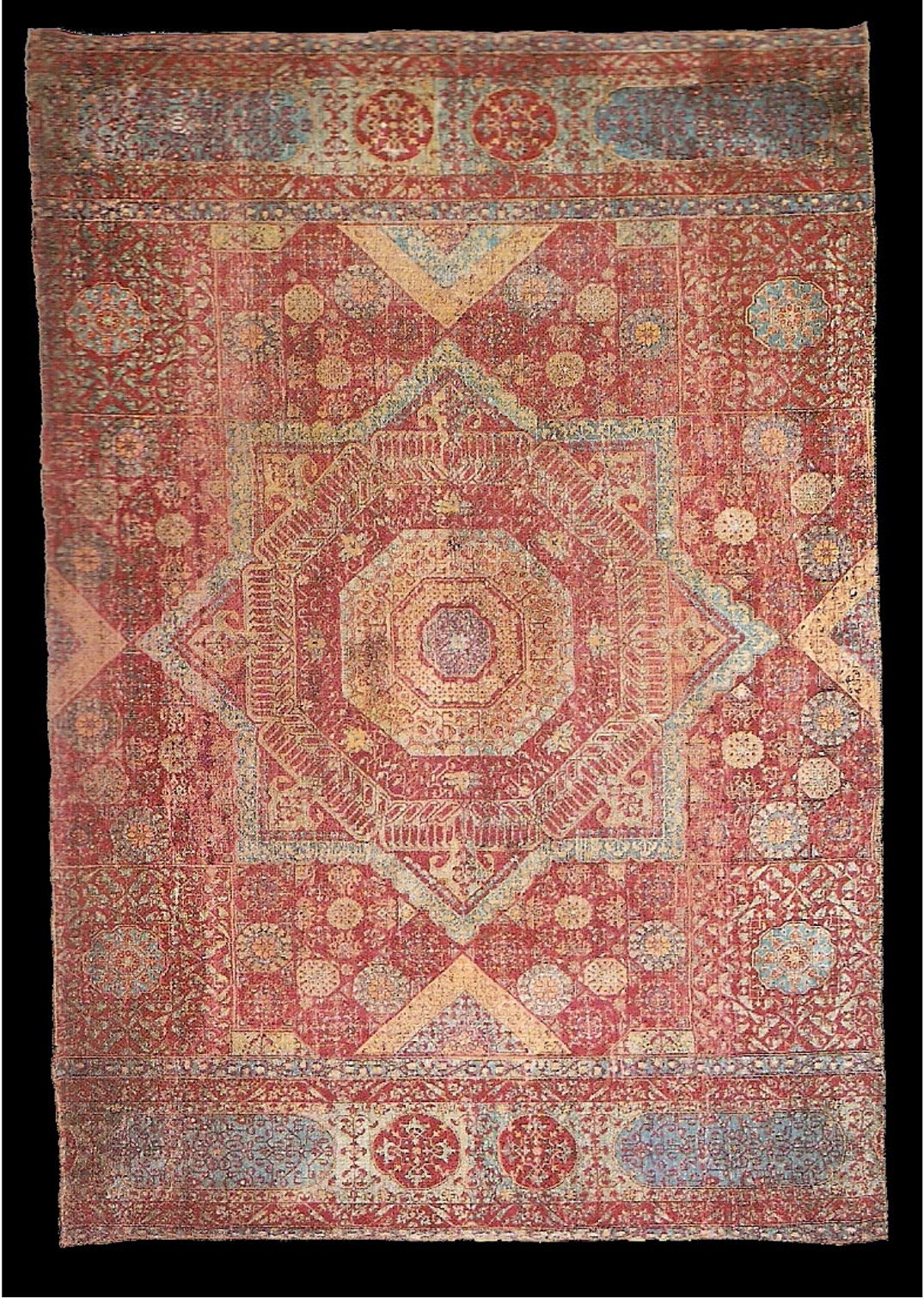

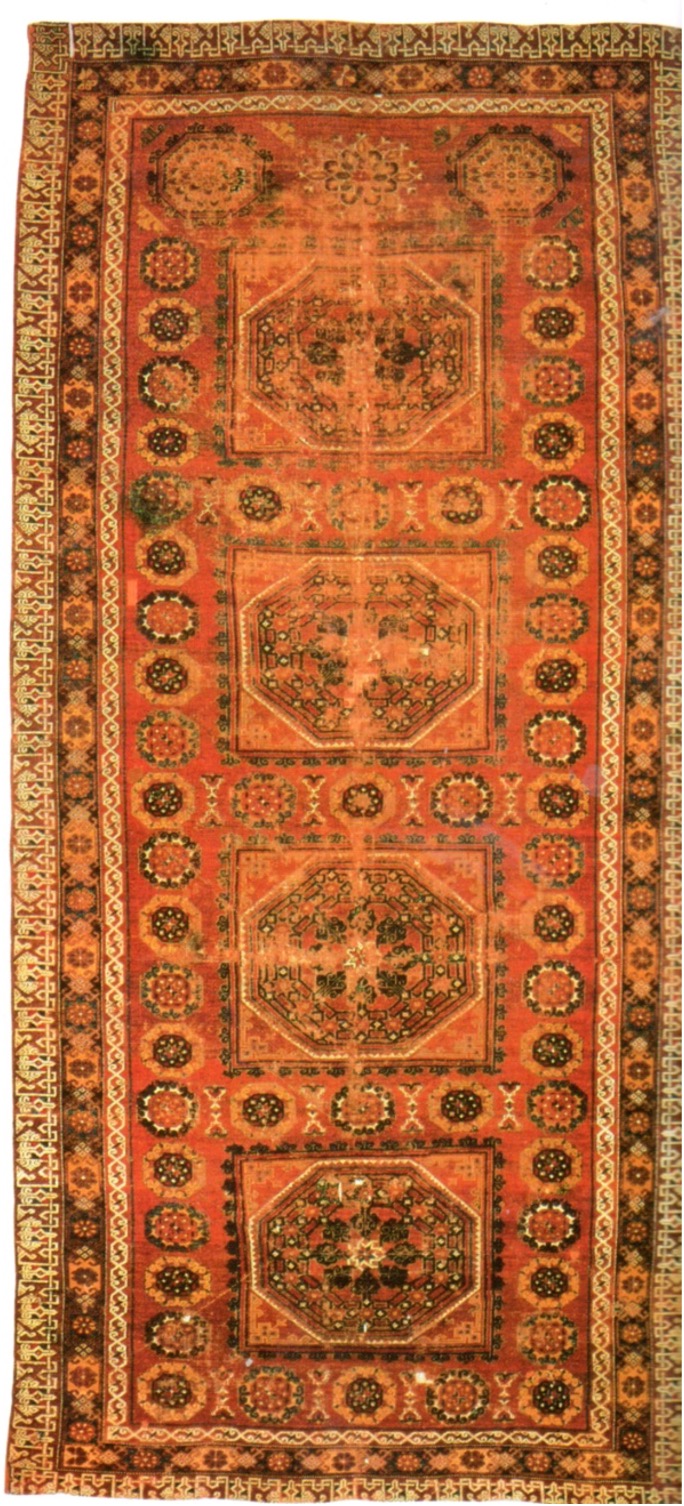

Wool Carpet, Cairo, Egypt, 1500

Prestige carpets, often used as tablecloths rather than on the floor to keep them clean

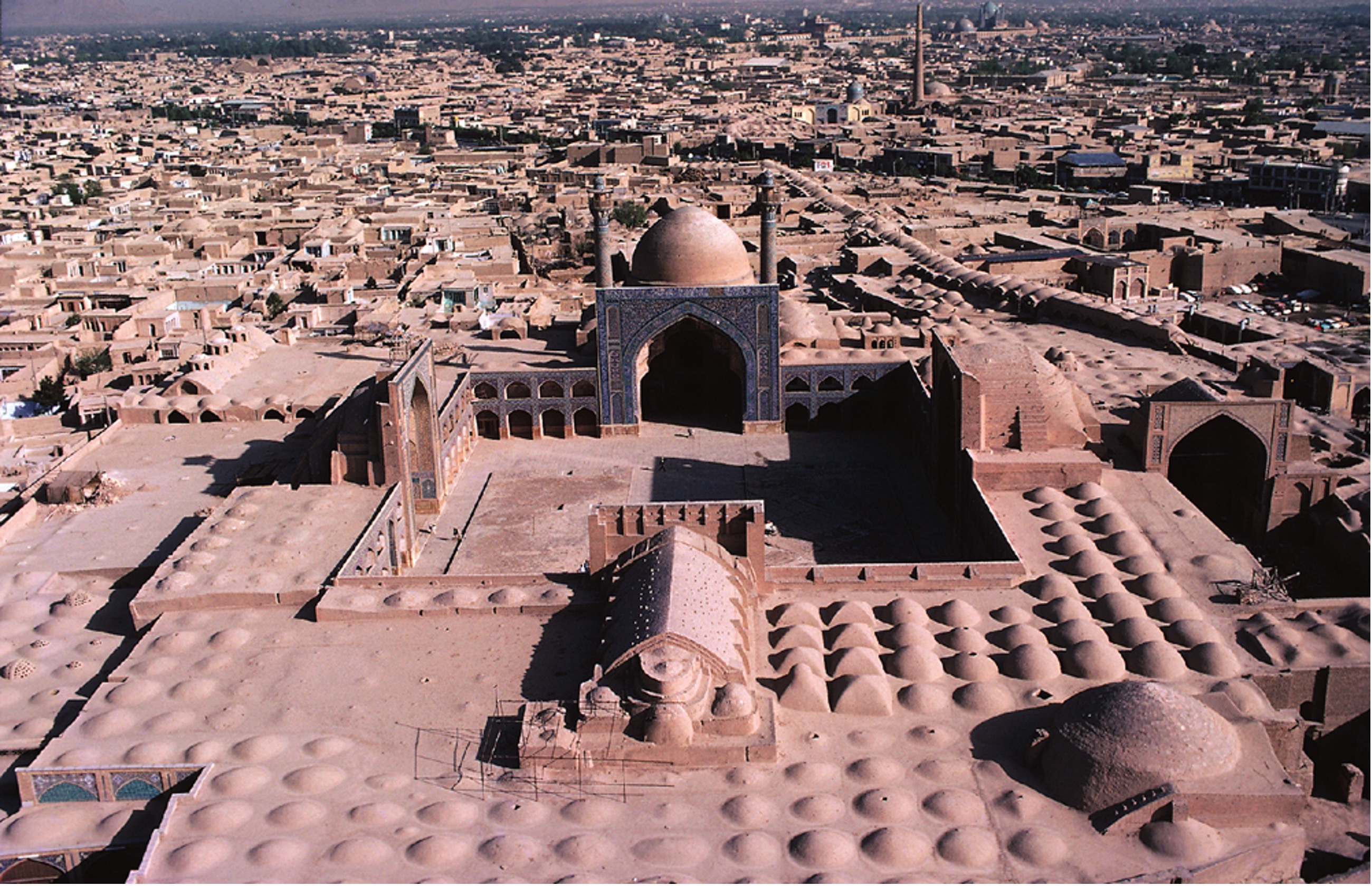

Great Mosque, Isfahan (Iran), 10th-11th century CE

It is the first mosque to use a true 4-Iwan plan

Holds articulated squinch similar to that of Arab Ata (8th century)

Development of the muqarnas

Monumental pishtaqs

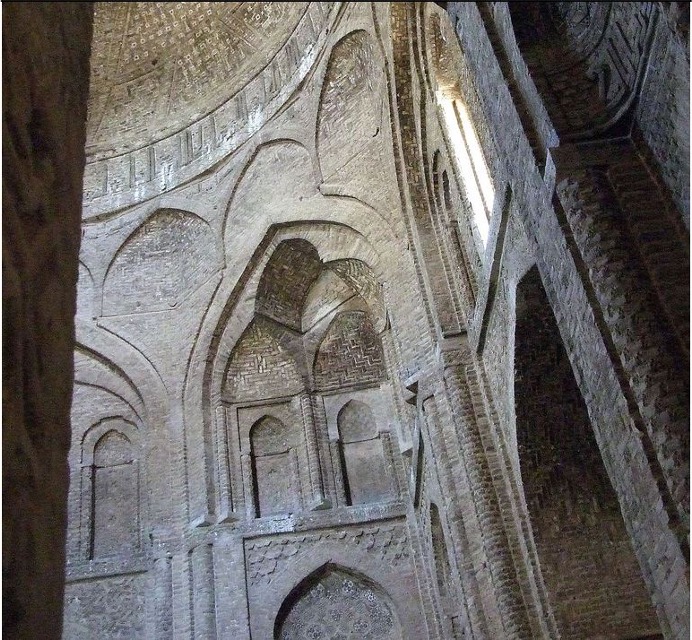

North Dome, Great Mosque, Isfahan (Iran), 1088 CE

Utilizes large articulated squinches/muqarnas

Very ornate geometric designs

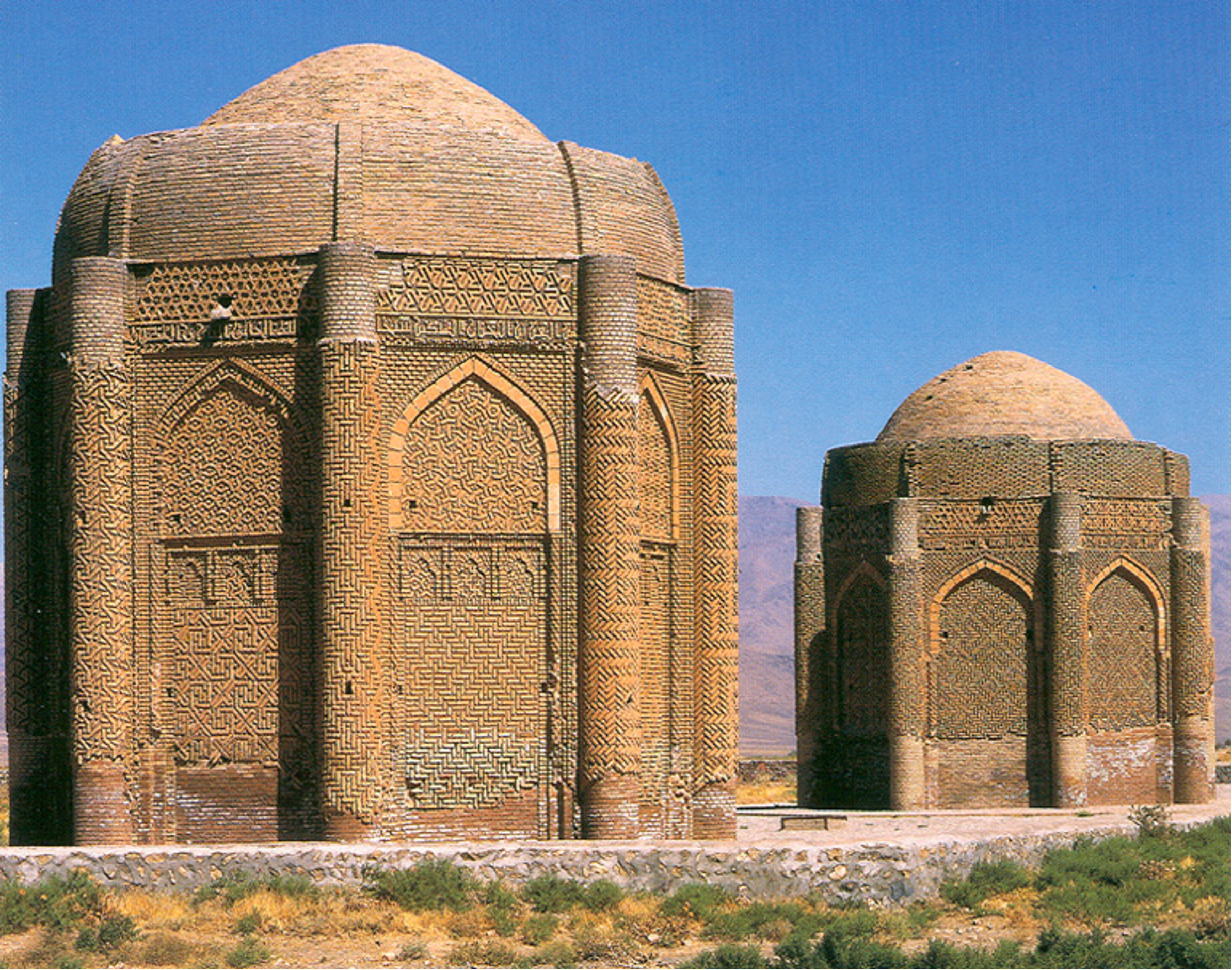

Mausoleum, Kharraqan (Iran), 1093 CE

Utilizes double-shell dome

Shape resembles Arab Ata (8th century)

Covered in brickwork and geometric designs

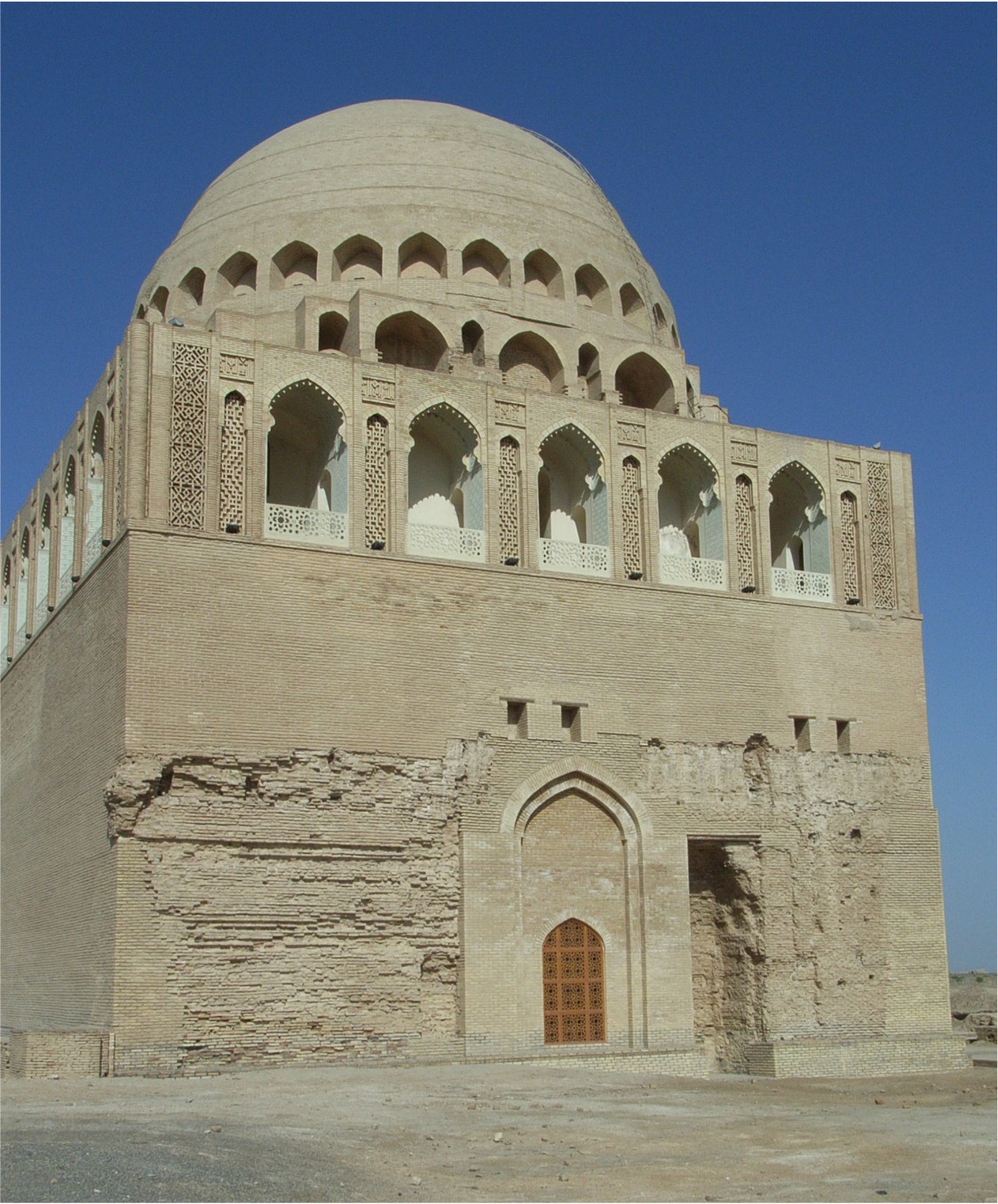

Mausoleum of Sanjar, Merv (Turkmenistan), c. 1152 CE

Light dome characterized by dark, simple geometric design on interior

Most of the dome is pretty much bare aside from the strap design

Mustansiriya Madrasa, Baghdad (Iraq), founded 1233

Mustansiriya uses a 4-Iwan plan, with some major changes

Only one of the iwans is used for a masjid – a prayer hall

A triple iwan forms the main entrance

The iwan opposite the main entrance has only one portal – but to keep the plan balanced, two false iwans are added on either side

The first madrasa built to house all four schools of Islamic law

The rooms on either side of the two main iwans are divided into four equal zones

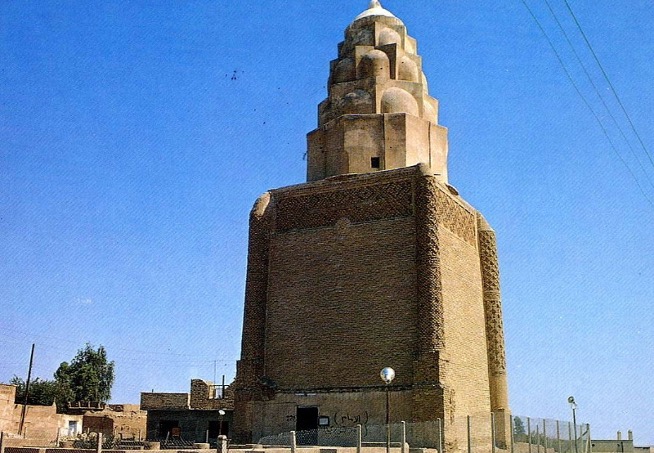

Imam Dur Mausoleum, Samarra (Iran), c. 1083

→ Mausolea in this period are different from any we have seen so far; the dome is replaced by a 3-D cone composed of muqarnas

Elevation of the Imam Dur Mausoleum – showing the repeating forms of the muqarnas and how they create the tall domical space

The repeated forms are multiplied by the linear decoration inside each muqarnas

It is possible that these muqarnas in the Baghdad area are an ideological representation of Seljuk sunnism – religious orthodoxy

Friday Mosque, Dunaysir (Koçhisar, Turkey), begun 1204

Anatolian Seljuks incorporated many regional styles that existed alongside the Islamic monuments

Use much more stone masonry, instead of the lighter brick used in Iran (has a lot to do with the colder climate in Turkey)

Armenian Christian architecture provided sources for decorative elements in Anatolian Seljuk architecture

The stone relief designs at Dunaysir are unlike anything we have seen so far, but strongly resemble Armenian architectural decoration

The mihrab niche at Dunaysir – using a polylobed arch that came from Umayyad Spain

Also has a very unusual muqarnas squinch in the corner near the mihrab

Friday Mosque, Diyarbakr (Turkey), 1191-2

Diyarbakr is a blend of motifs from Classical Antiquity, the Byzantine Empire, and local traditions

Byzantine figured columns, classical vine pattern border, Arabic script border, etc.

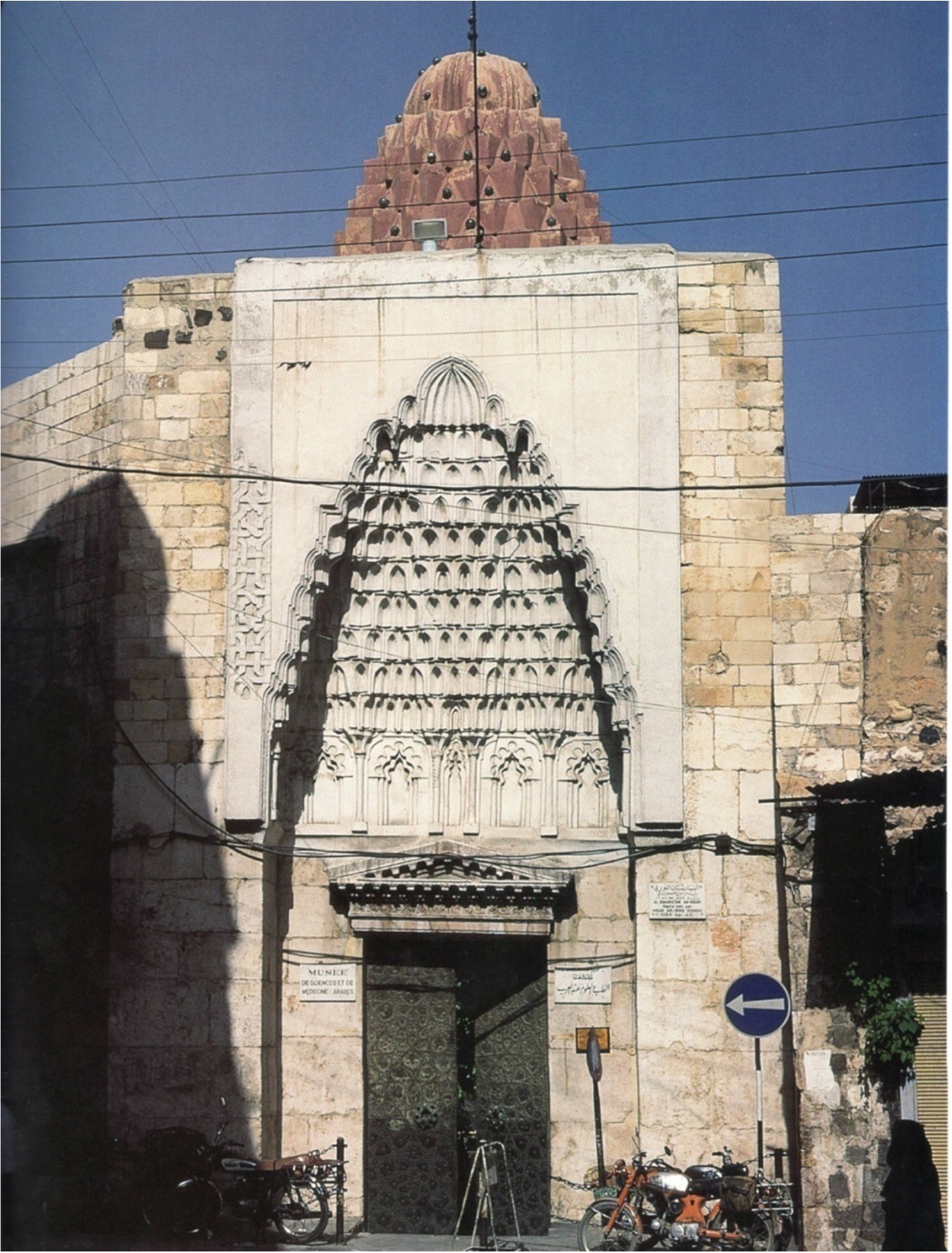

Façade, Hospital of Nur al-Din, Damascus (Syria), 1154

→ Seljuk hospitals were the best in the world

Image shows a ½ muqarnas dome as the ornamental pishtaq, but places it over a triangular Classical pediment on the actual door

The muqarnas entrance echoes the dome behind it – both the exterior (which you can see above the entrance), and the interior muqarnas once you go inside the building

Khuand Khatun Külliyesi, Kayseri (Turkey), 1237-38

Kayseri is in Central Anatolia (the first capital of the Seljuks of Rum)

Khuand Katun was the wife of one of the Anatolian Seljuk Sultans

Very simple, stark stone construction – also based in part on Armenian architecture

Inside has virtually no decoration

The mosque at top is hypostyle, but has no courtyard (and is smaller, so easier to heat)

A simple dome covers the central square, and another is over the mihrab niche

Central dome uses a Byzantine arrangement It uses a dome pierced with windows, and simple pendentives instead of squinches

Pendentive: alternate solution for creating a circular space for a dome in a square room – a slightly curved, 3-D triangle in each corner of the cubic room

The entrance is on the right side, to keep it closer to Khuand Khatun’s tomb, which has complex geometric ornamentation carved into the stone)

This külliye (mosque complex) had the mosque, the tomb of the founder, and a madrasa

İnce Minareli Madrasa, Konya (Turkey), 1258

Seljuk madrasas are smaller → they abandon the 4-Iwan and courtyard plan used in Iran for a monumental pishtaq, with two domed rooms on either side of the façade

The central space, once open, is now covered with a dome

İnce Minareli means ‘slender minaret’

Decorated similarly to the dome, but also uses curved glazed bricks to construct the ribs

The areas between the ribs are not flat, but curve outwards to make the minaret swell

The ceramic tiles making the diamond design are also three dimensional – they are like small pyramids or square studs attached to the brick

The dome of the central space is placed on fan shaped angular pendentives, instead of the curved ones used at Khuand Khatun

The result is a circle at the top made up of 20 very small arcs, which give a “scalloped” look to the bottom of the dome

Typical Anatolian Seljuk decorative brickwork mixed with turquoise-glazed ceramic tiles

The pishtaq uses both heavy, sculpted 3-D motifs and delicate carved borders

A blend of local traditions (mostly Christian) in the heavy designs, with thuluth Arabic in the borders

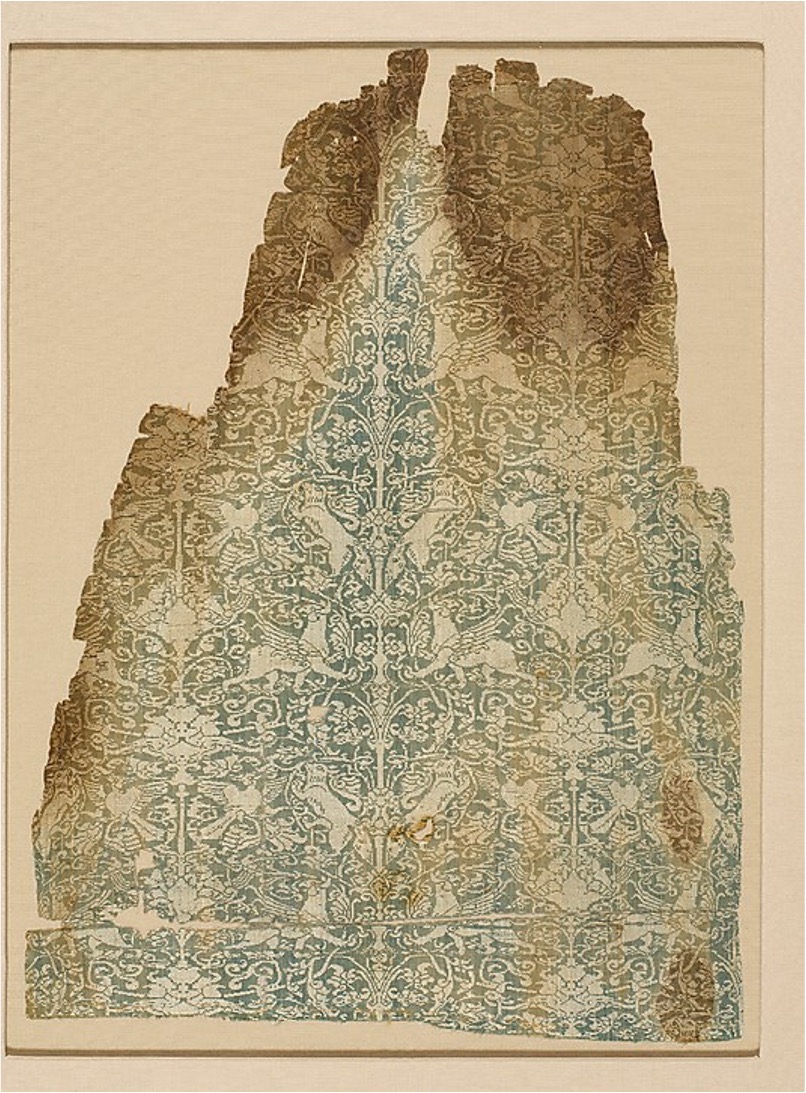

Silk Fragment, Mosul (Syria), 13th century

Mosul was famous for its textiles Muslin (or mousseline) is named after the town

Silk was also produced here and exported to the West

The quality was extremely high, and the designs developed out of Sasanian and Byzantine designs

Instead of placing senmurvs in beaded medallions, as had been done for centuries, the artist designing this fabric incorporated them into an overall, repeated arabesque design

Tile Panel, Konya (Turkey), 13th century

While the Jazira produced fine textiles and glass, Konya developed a new form of architectural decoration – the tile panel

It was different from both mosaic and from the ceramic wall mihrabs produced in Iran, since it was larger than mosaic, but could produce an infinite repeat (mihrabs were designed for one specific location)

Mihrab, Sırçalı Madrasa, Kanya (Turkey), 1242

Example of cuerda seca, a new type of ceramic was developed to be able to create polychrome designs

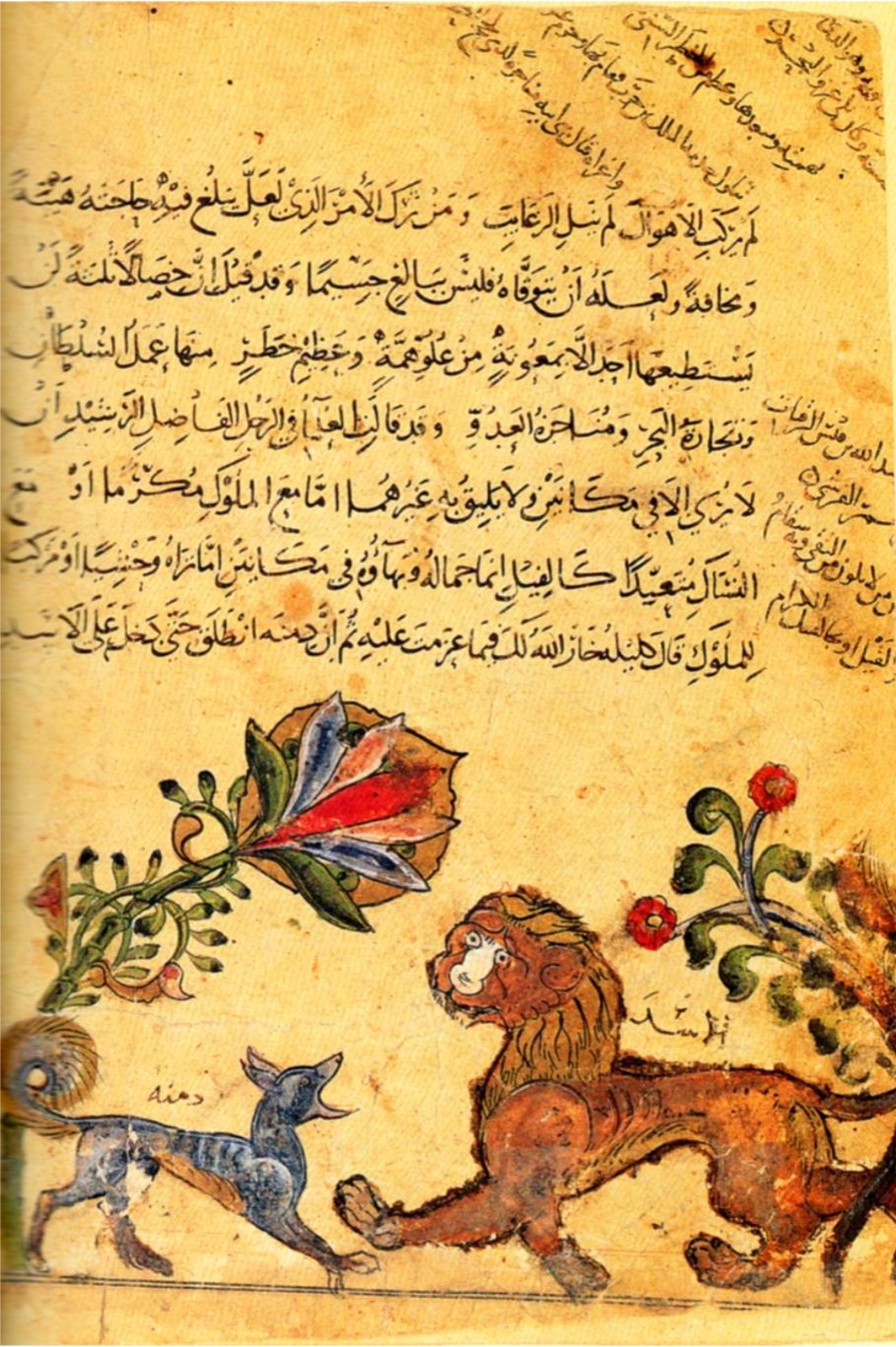

Kalila wa-Dimna, Konya (Turkey), 13th century

Tile panel using cuerda seca could be put together like a jigsaw puzzle to create entire walls, or to build ceramic mihrabs similar to those of 10th-century Iran

Maqamat of al-Hariri, Konya (Turkey), 1237

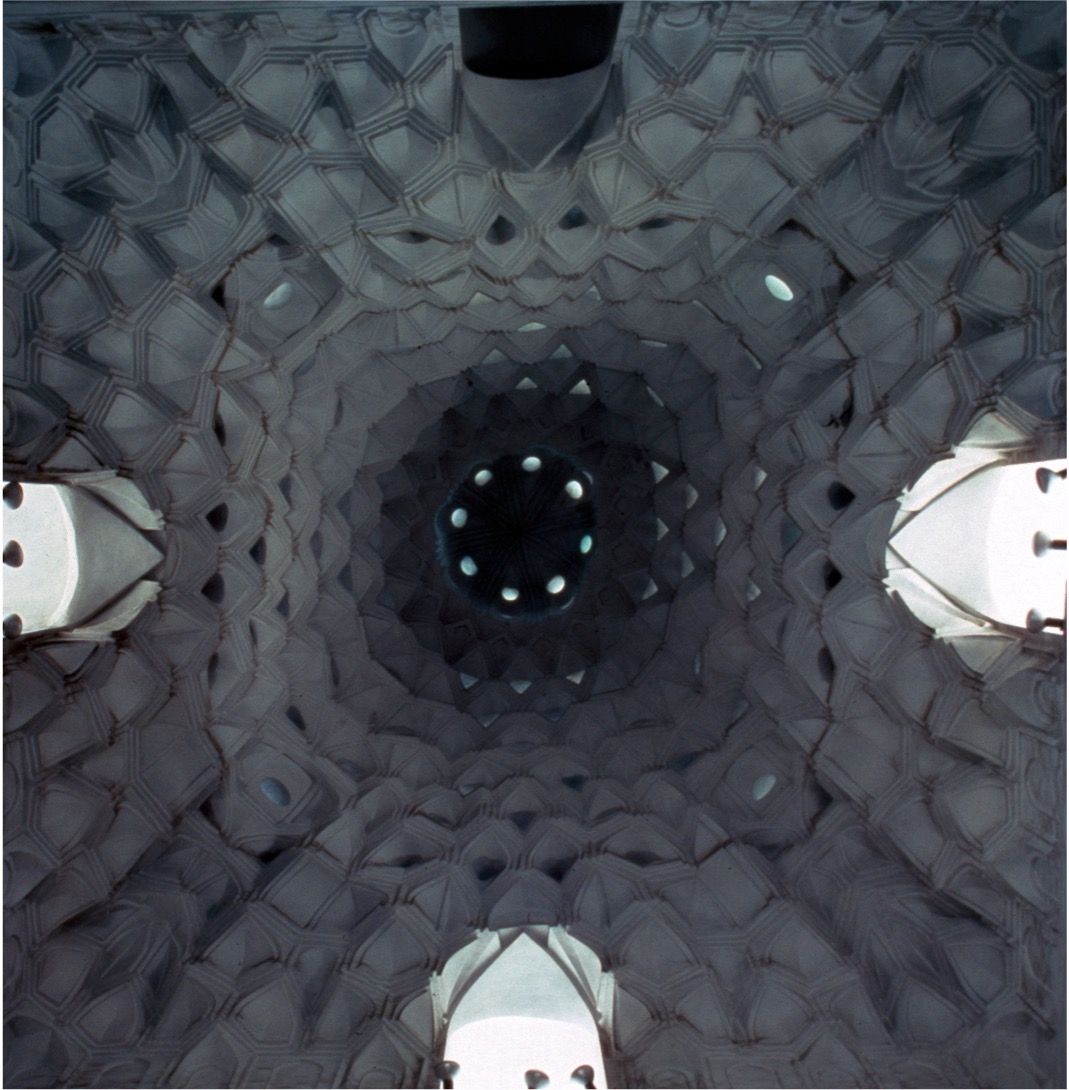

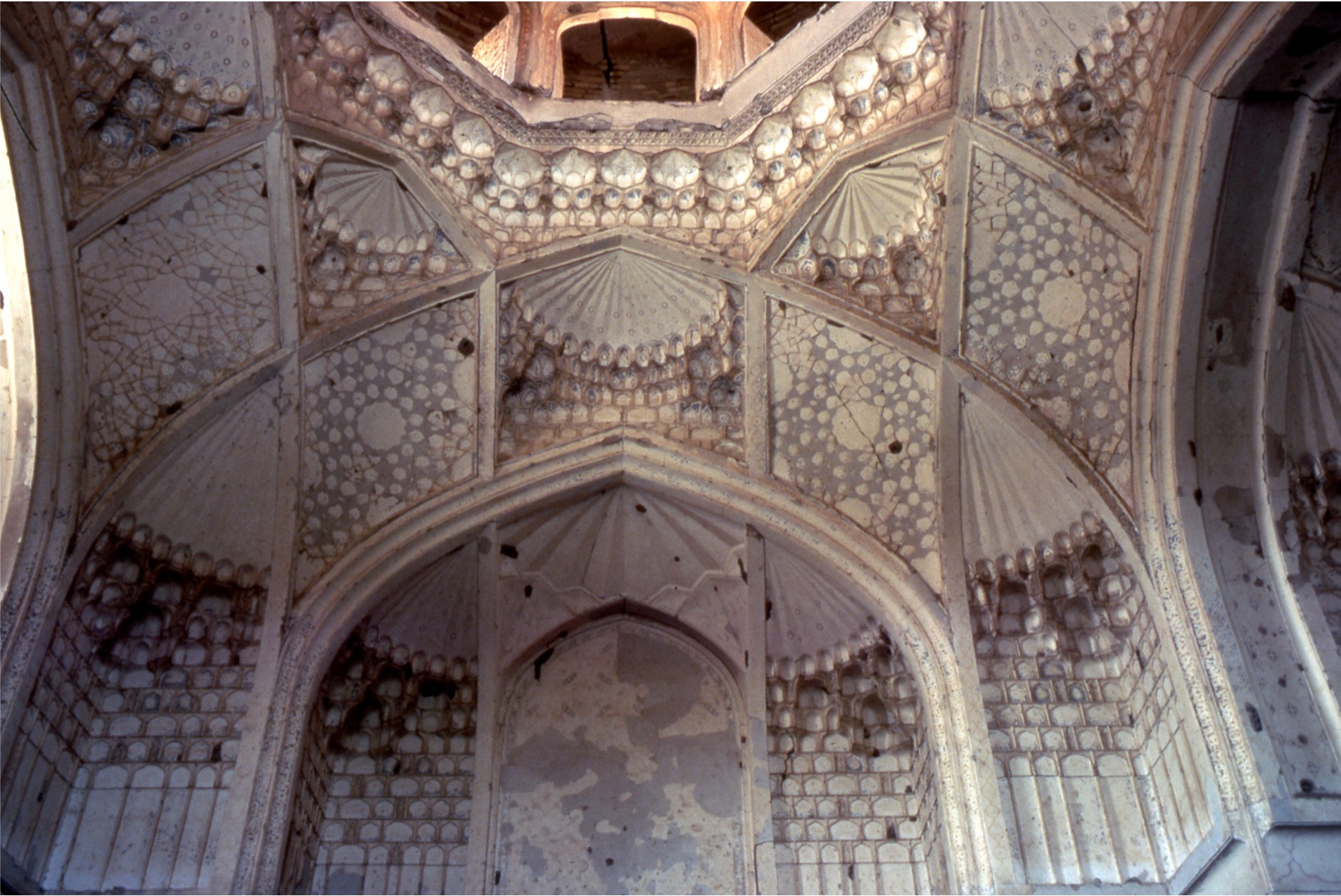

Muqarnas Dome, Shrine of Ahmad Yasavi, Turkestan City (Kazakhstan), 1379-96

Similar to Seljuk architecture is the use of muqarnas in the vaulting

The most elaborate ones are over the shaykh’s tomb and in the mosque – but also in the central space here

They had never been used on such a monumental scale in the past

Gur-i Mir (Tomb of Timur), Samarqand (Uzbekistan), c. 1400-04

Built originally as a madrasa , it was converted to a mausoleum

The tomb space is not square, but rather a kind of cross-in-square plan

The interior is quite rich, with different colored marbles and pierced stonework

Note how the change in plan from square to cross-in-square gives a more complicated visual aspect to the space

The exterior shows the continuation of the Seljuk aesthetic, with blue and turquoise glazed brick combined with uncolored ones to make a “brick mosaic” of geometric kufic patterns

The most surprising element is the dome over the tomb, which has a very high profile and is covered with fine ribs completely encased in curved cuerda seca ceramic tiles fired to conform to the ribbing

The high profile is a “false” dome, held up by wooden supports springing from the lower inner dome

The construction is very stable – it has survived earthquakes

The interior of the dome, showing its lower profile, along with the simple “muqarnas” shaped squinches alternating with ship’s keel arches

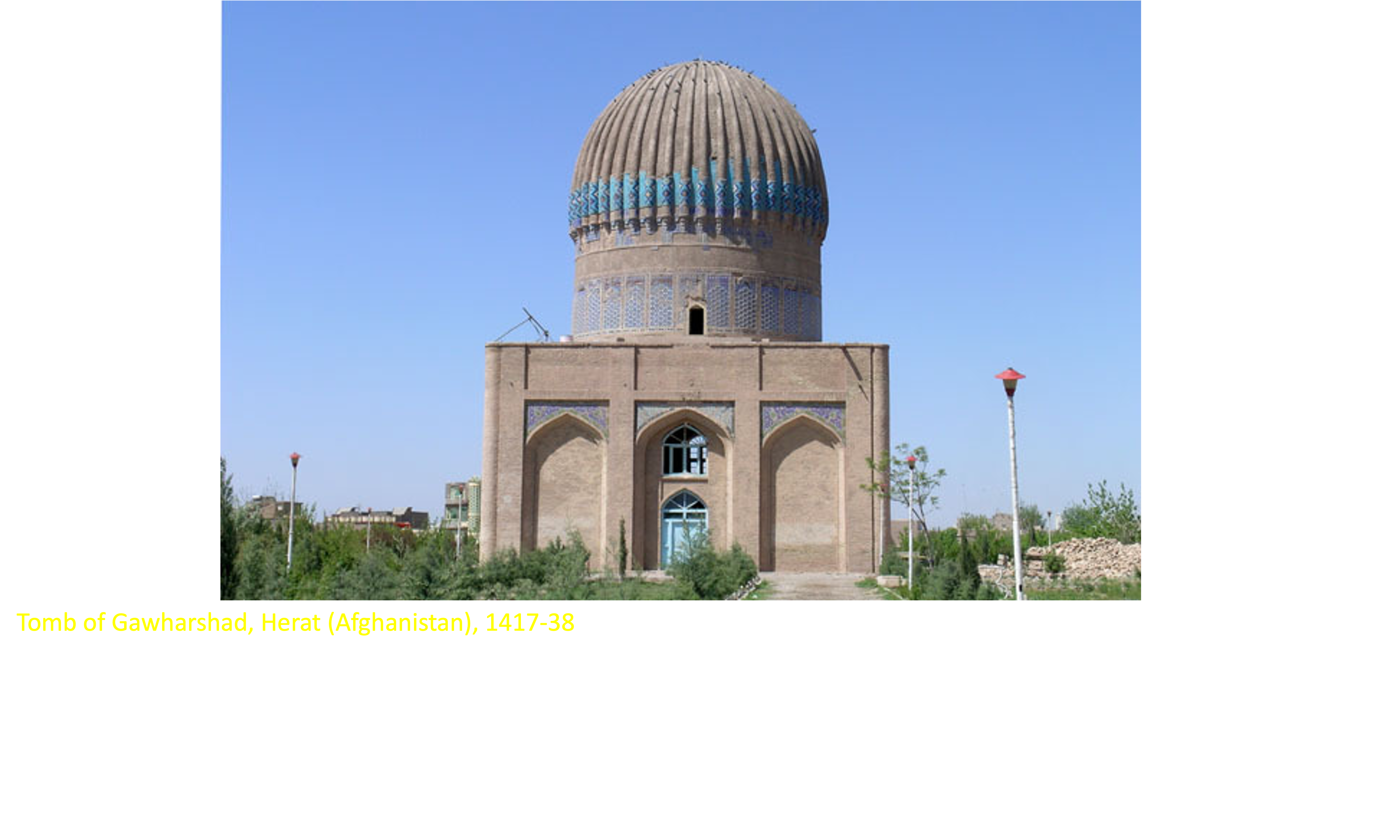

Tomb of Gawharshad, Herat (Afghanistan), 1417-38

Although the façade is very different from Timur’s architecture (three equally spaced blind iwans instead of one large one), the plan is the same cross-in-square, with the same high-profile dome

These high domes serve the same purpose as the tall muqarnas cone found on the Imam Dur Mausoleum (Seljuk) in Samarra – it makes them more visible from afar

The ribbed dome had muqarnas corbels at the bottom of each rib

Gawharshad’s tomb is one of the first great examples of the use of the squinch-net

The squinch-net is an elaborate system of vaulting using squinches and transverse ribs, with the areas between the ribs as well as the squinches are filled with muqarnas

The areas in between the transverse ribs are then filled with a stellar or fan shaped pattern that is supported by muqarnas in the bottom half

This will only work with a cross-in square plan

Ghiyathiyya Madrasa, Khargird (Qiasieh,Iran), 1442-45

Squinch-net from the center of the room

The rim around the dome center is ringed by individual muqarnas motifs that resemble a pearl necklace

The fan shapes in the high corner elements burst into muqarnas, which then reduce down in 3-dimensionality, ending in a low relief vertical ribbing that echoes the fans at the top

Instead of a closed dome, the ceiling rises to a low lantern with windows that allow in the light

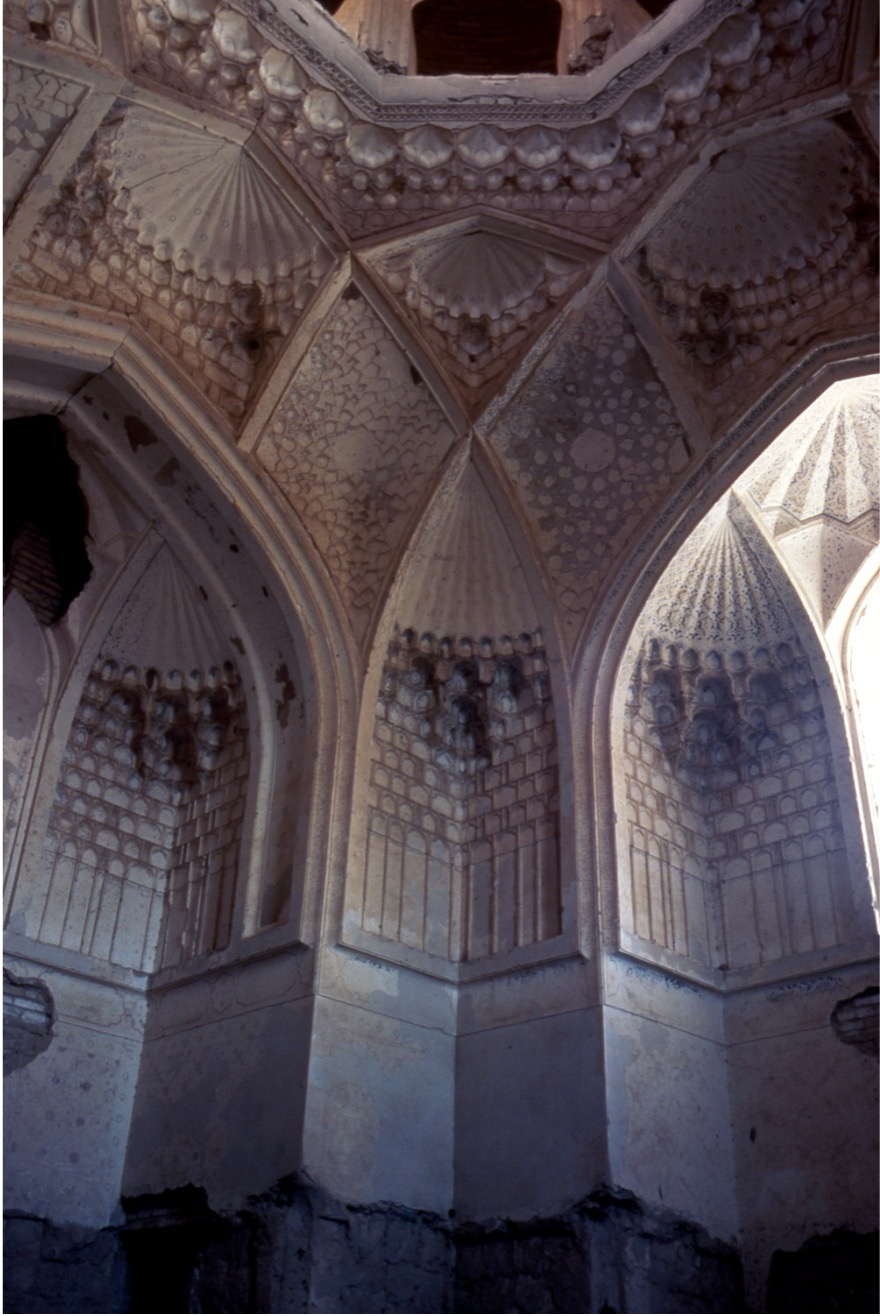

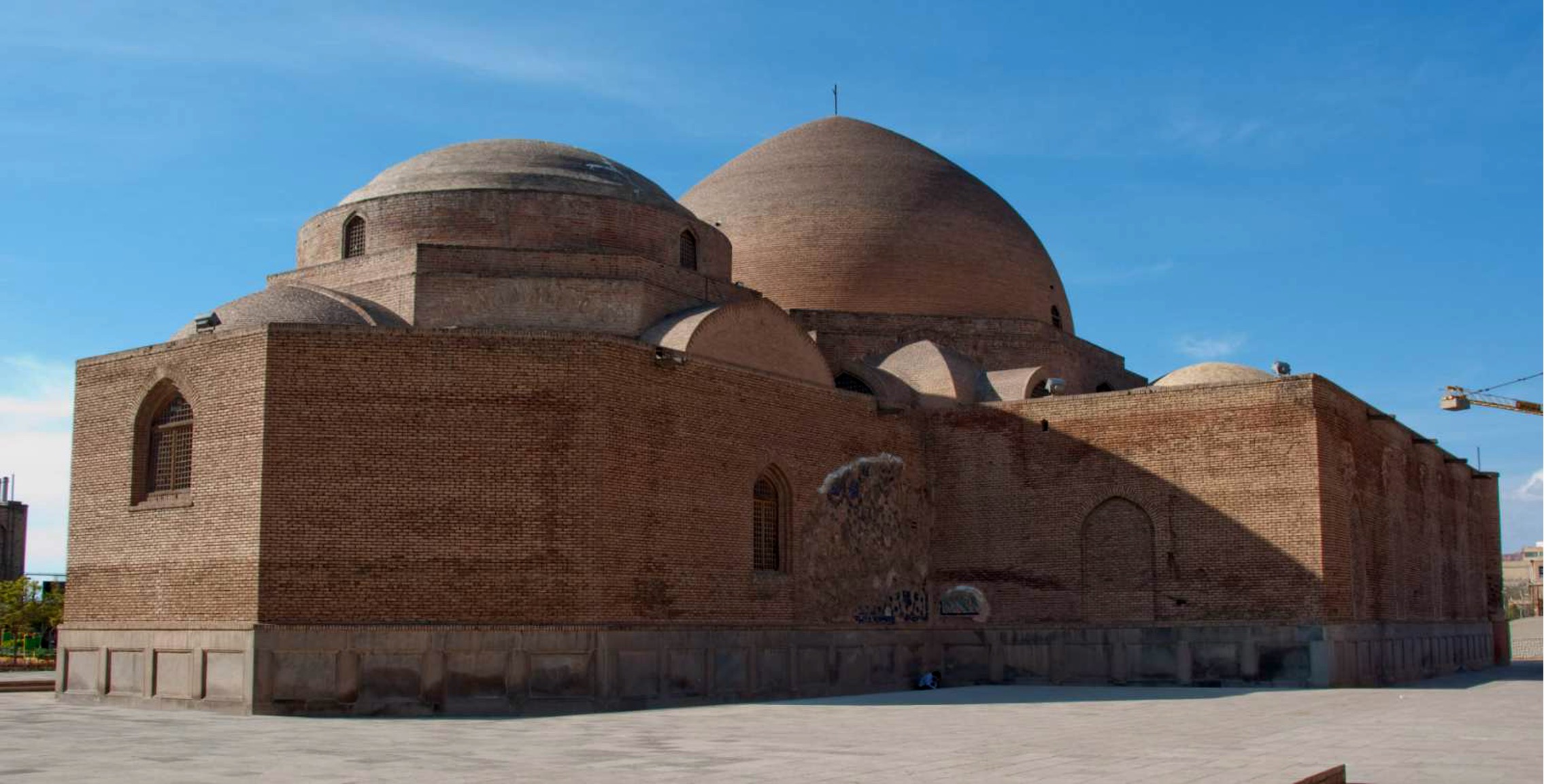

Blue Mosque, Tabriz (Iran), 1465

A group of Turkeman tribal confederations rose in Eastern Anatolia and Northern Syria known as the Black Sheep and the White Sheep

The Black Sheep (ruled from 1380 to 1468) made Tabriz, Iran their capital

The Blue Mosque is the only building remaining from their reign

The Blue Mosque is built around a large central domed space, with a second domed room facing the qibla, and a U-shaped vestibule

It was a multi-function complex, but the different spaces have not all been identified

The central space and dome – set up in a configuration similar to that of the Gur-i-Mir, but with a simple square space instead of a cross-in-square plan

The dome was once covered with deep blue hexagonal ceramic tiles

It is called the Blue Mosque for the stunning tile revetment, displaying the highest quality Tabriz ceramics in the city’s history

Porridge Cauldron from Shrine of Ahmad Yasavi, c. 1396

Timur also commissioned huge standing oil lamps and this giant cauldron for Ahmad Yasavi

The bronze cauldron is 1.58 meters high, and 2.43 meters wide

It was used to serve porridge in a Sufi ceremony ending the fasting month of Ramadan

The shape (as well as the hanging metal pendants) come from China, while the arabesques and calligraphy are pure Islamic

Good example of the Chinese influence on allied arts

Timur granting an Audience at Balkh, (Zafarname), Shiraz (Iran), 1436

The first Timurid books were commissioned by his son, Shahrukh (Gawharshad’s husband)

He preferred historical subjects, but quickly Timurid contacts with Persian book arts caused their artists to change their style

This copy of the History of Timur was commissioned by his grandson

The composition is mostly composed of figures – with limited background details and subdued colors

Note the cloud-like tree at upper left (very Chinese)

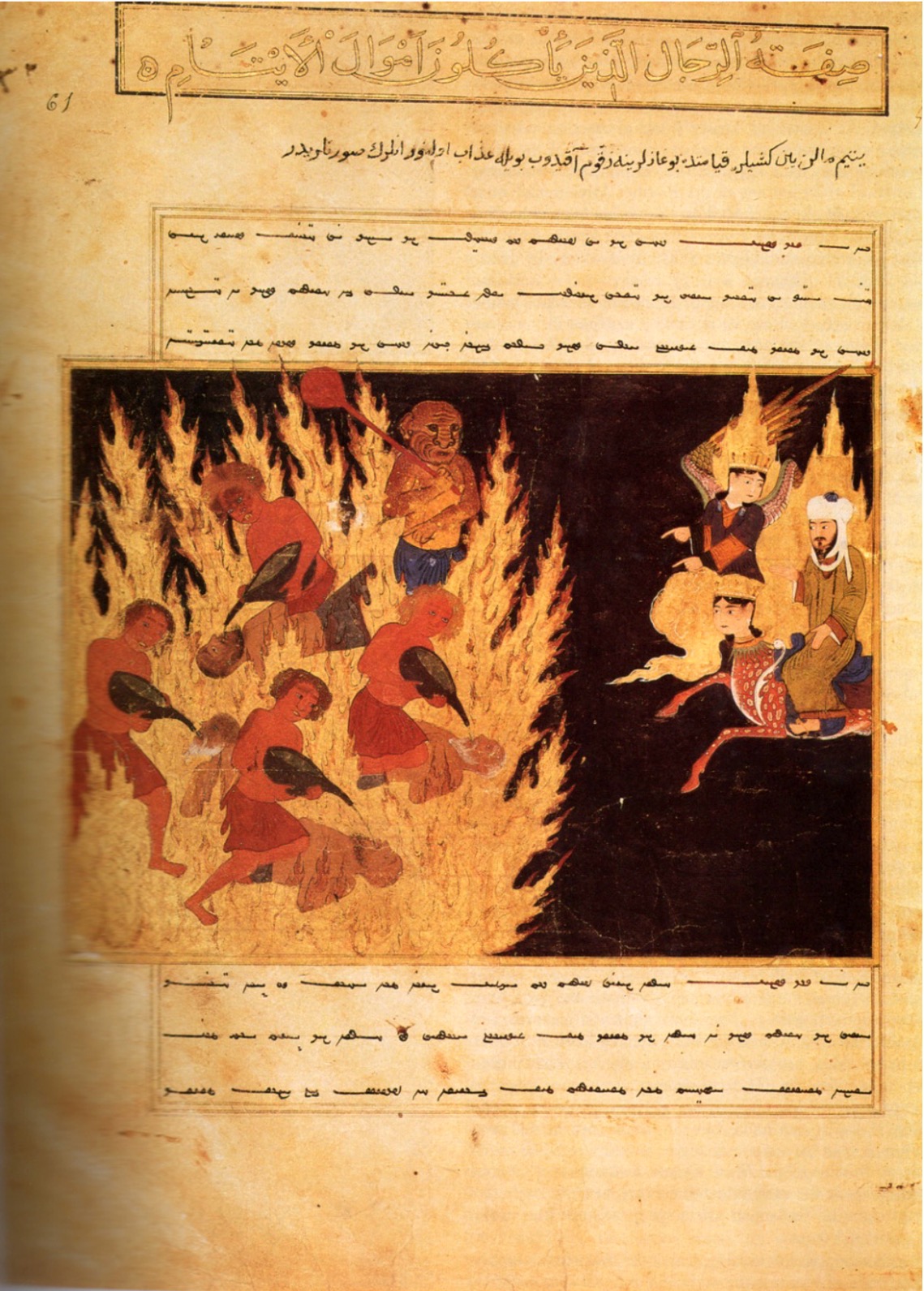

The Torment of Those who Squander the Inheritance of Orphans, (Mir'ajnama), Herat (Afghanistan), 1436

Herat, in Afghanistan, was another important center for book production

This manuscript illustrates the journey made by Muhammad (riding his mythical steed Buraq) and the angel Gabriel to hell, where he views the various torments

Two standpoints: Muhammad’s face is uncovered and is fully painted, and the demons bear a strong resemblance to depictions of demons in the animist Turkeman religion that existed long before the arrival of Islam

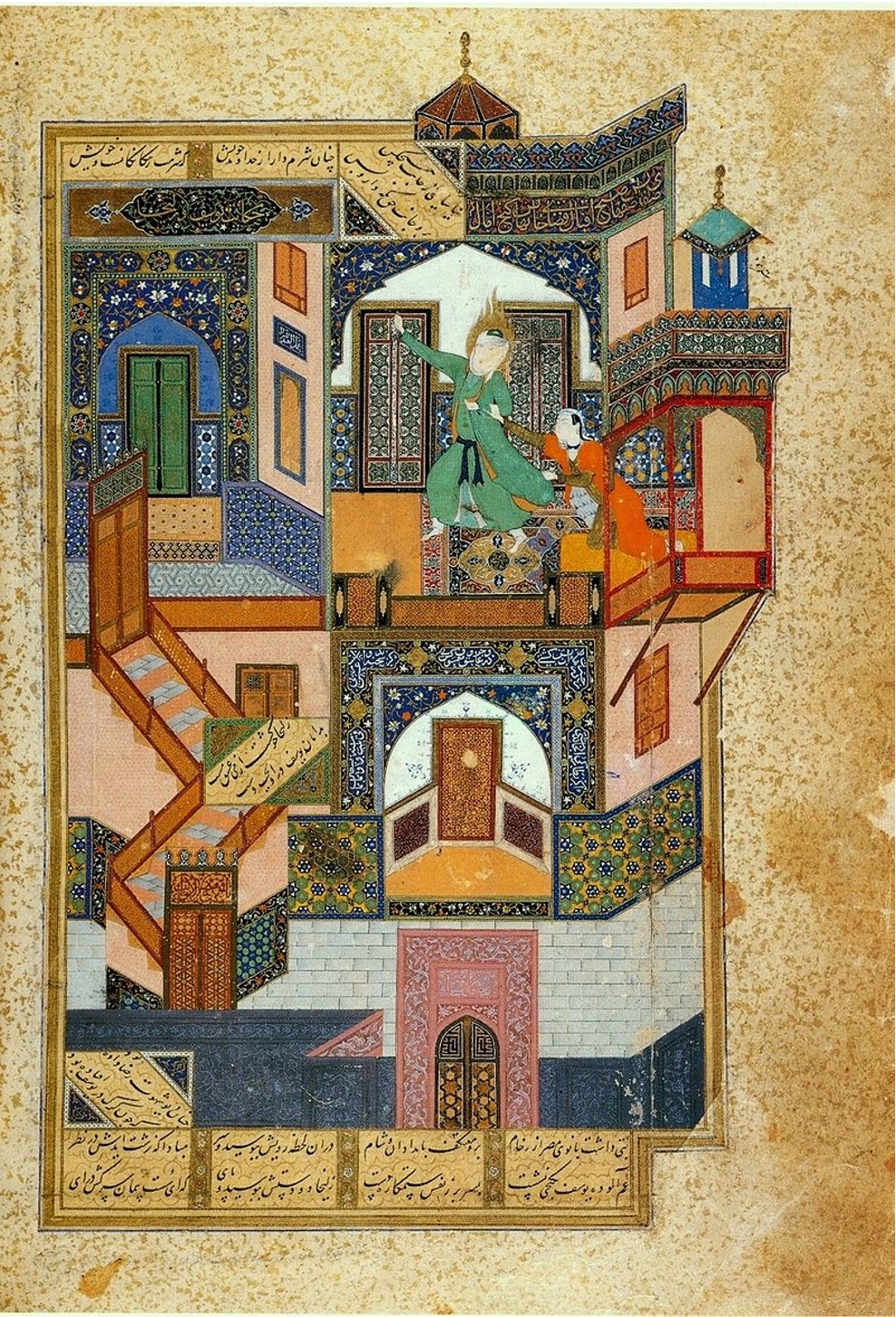

Bihzad, The Seduction of Yusuf, (Bustan), Herat (Afghanistan), 1488

Bihzad was the most famous Timurid book illustrator

He began working for the Timurid sultans, but eventually wound up in Tabriz, where he was head of the Safavid shah’s book workshop

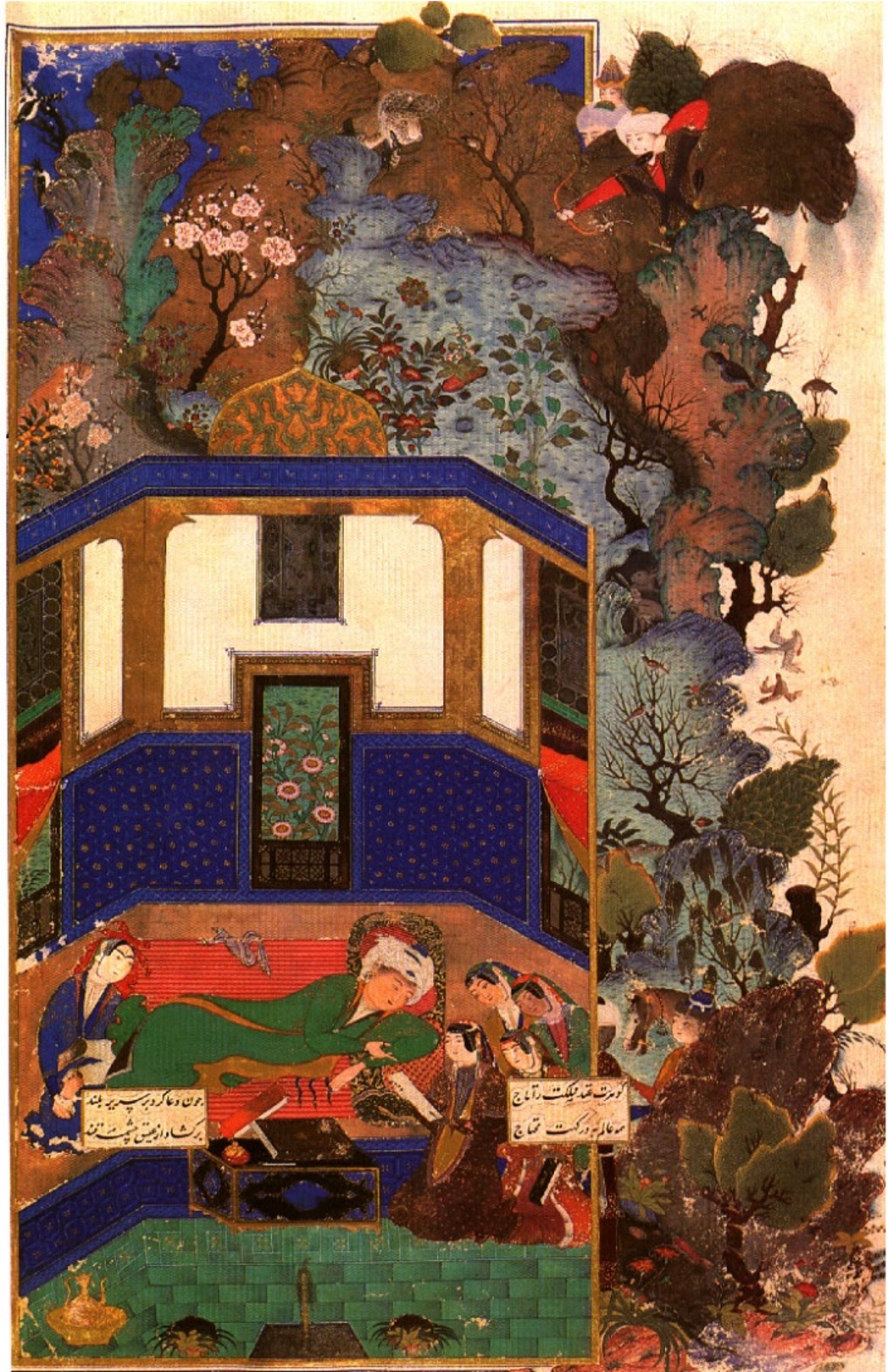

Shaykhi, Bahram Gar in the Green Pavilion (Khamza), Tabriz (Iran), 1480's

The story of this book is very complex – it was begun under one of the princes of the Turkeman White Sheep confederations and passed to several relatives after that prince died

It ended in the hands of Isma’il I, the founder of the Safavid dynasty, - who finally had the book finished

Mosque of Orhan Gazi, Bursa (Turkey), 1399

An example of a Zaviye Mosque

The “arms” of the T were allocated to traveling Sufi dervishes, who used them as hostel while on the road (“Sufi hostel”)

Highly unusual squinches – the emergence of the “Turkish Triangle”

Isa Bey Mosque, Selçuk (Ephesus, Turkey), 1375

A different form of congregational mosque associated with the Beylik principalities

Closer to the most ancient mosques (Great Mosque of Damascus), with a long, shallow, two-bay hall and courtyard, but the hall is intersected by two central domes

The pishtaq is now 3-D, forming an Entrance Block, and decorated with an inlayed stone interlace pattern based on Seljuk designs

Multi-media: different colored marbles, low relief arabesques, and muqarnas

Actually very little carved ornamentation

Sculptor used muqarnas to create a window frame, wrapping them around the window opening

The interior is extremely stark and plain but contains spolia from the ruins of the great Hellenistic city of Ephesus nearby

The mihrab is also simple and stark, with black marble inserts in an interlace pattern that complements the entrance

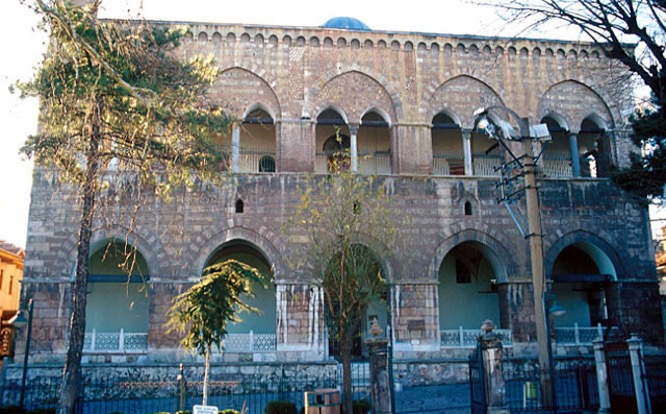

Mosque of Murad I (Muradiye), Bursa (Turkey), 1366-85

Shows a traditional Byzantine building technique - rows of brick alternate with rows of white stone

Façade is very similar to Venetian or Italian medieval facades, making architectural historians suspect an Italian architect

This mosque is built on two levels, with a ground floor and a second story

Ground floor – a modified Zaviye plan, with a central dome, mihrab space, vestibule and porch, and the side Zaviye

2nd floor - functioned as a madrasa, with rooms for the students and for study, making the Muradiye a true multi-function mosque

Another important feature: the porch, where muqarnas are replaced with Turkish Triangles

The Turkish triangle could also be used to transform column capitals, and in this case, the rim around the porch dome

Interior: very simple, barrel vaults, round-headed arch headed to mihrab area, column-less architecture

The interior also has an Italian feel, w/ its emphasis on the walls and vault

The central space is designed much like the Arena Chapel in Padua (Italy), built about 50 years earlier

Another feature of early Ottoman mosques: an interior ablutions fountain in the center of the hall

Ulu Cami (Great Mosque) of Bayazit I, Bursa (Turkey), 1396-1400

A hypostyle congregational mosque (note the rows of domes)

Simple in its exterior design, using the traditional Seljuk masonry

Plan combines a domed hypostyle prayer hall with the interior fountain – but eliminates the porch, vestibule and zaviye

The Ulu Cami, in contrast to Bayazit’s own complex, was built to serve the people of Bursa, so the older hypostyle plan served that purpose better

Pishtaq is a monumental entrance block with a muqarnas arch similar to the entrance at the Nur-al-Din hospital (Seljuk) in Damascus

Interior – plastered piers replace columns (the painted decoration is later)

The walls are perfect grounds for the calligraphy, which were commissioned by citizens of Bursa as votive gifts

Also has an interior fountain

The decoration is focused on the mihrab, with gold ornamentation and stained-glass windows

Central dome (over ablutions fountain) is pierced w windows and rests on pendentives, like Byzantine church and architecture

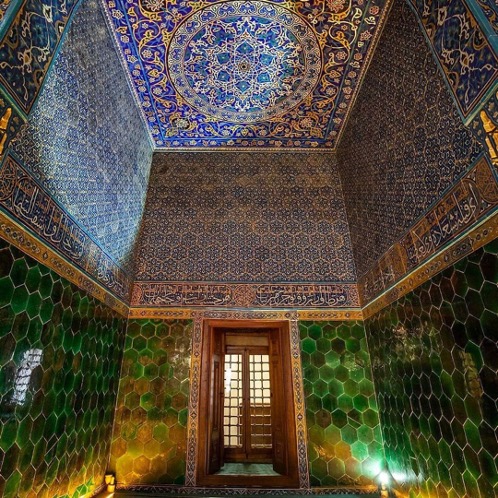

Yeşil Camii (Green Mosque) of Mehmet I, Bursa (Turkey), 1412-24

Tomb of Mehmet I is actually on a hill higher than that of the mosque – very unusual and not really proper

A classic Zaviye mosque

Top of the interior: an ornamented Turkish triangle ring around the base of the central dome

Huge mihrab niche covered in ceramics with the Seljuk muqarnas niche

Walls of the zaviye are tiled in hexagonal, emerald green tiles, with medallion inserts of cuerda seca interlaces

The entrance block pishtaq retains the traditional muqarnas arch design

However, the design is a hybrid of muqarnas and Turkish triangles, with little bosses attached to the bottoms of several of them

Windows are decorated with finely carved arabesques, and surrounded by muqarnas (like at Isa Bey Camii)

Very fine carving uses floriated kufic, arabesques in the center, and a thuluth inscription

The Yeşil Türbe (Green Tomb) of Mehmet I

The walls of the tomb and Mehmet’s cenotaph are covered with turquoise ceramics – hexagonal tiles on the walls, and cuerda seca ornaments with cobalt blue, gold and white ornaments and calligraphy

Üç Şerefeli Camii (Three Balcony Mosque), Edirne (Turkey), 1437-47

Named for the three balconies on the minaret in the foreground

Has two new elements

An integrated fountain courtyard (instead of the interior fountains seen in Bursa)

The monumental single dome in the center of the mosque

With one dome considerably larger than the rest, exterior design that builds up

There are some awkward areas in the building (despite even plan)

Had 4 minarets

The prayer hall is long and narrow, like the Isa Bey Mosque, but Üç Şerefeli had only the large central dome, resting on six piers, with transverse arches connecting them to form a hexagon on which the dome rests

Result is a large, open, centrally planned space within a rectangular hall

Pendentives are more like the center section of a wall between two arches (called a spandrel) that simply curves around the corner

The architect uses Turkish triangles in a muqarnas format to ring the bottom of the dome (decorations beneath them that look like “inside out” muqarnas)

Ceramics are used sparingly, but the ceramics are of the highest quality

Made of blue and turquoise under-painting on fritware, they were made by artisans from Tabriz, in Iran

Şehzade Camii, (Mosque of the Crown Prince) Istanbul (Constantinople, Turkey), 1545-8

Complex was a true Ottoman külliye – containing mosque, madrasa, soup kitchen, bathhouse, dormitories, and the tombs of Mehmet and several other family members

Plan follows that of Hagia Sophia in many ways – but Sinan placed two more half domes around the main one, making a clover-leaf design

Plan abandons early Ottoman design w/ a fountain incorporated into mosque itself, in favor of the enclosed courtyard and fountain at Üç Şerefali Mosque

However, Sinan’s architecture is perfectly balanced and coordinated

Interior: the same canopy dome system (piers support all the weight)

White walls and large piers that carry the weight of the dome – wanted lines of his architecture to stand out

Canopy piers → cut the corners off the square profile and carved a muqarnas arch into the resulting angle to lighten the effect, then added a ribbed section so upper part of the pier would match the white arches around it

Only area in the mosque showing any gold is the mihrab – continuing the Early Ottoman convention of concentrating all ornate decorative work around mihrab niche

Dome had Ottoman stenciled designs

Used mostly paint to decorate their mosques, rather than ceramics, mosaics, or marble inlays

Red and white arches are a direct reference to the bi-colored arches in the Dome of the Rock

Since there are so many repeating forms, there is a kind of harmony in the architecture

Design also allows for the insertion of many windows, which allow a great deal of light to enter the mosque

This, plus white paint on the walls and white marble construction, allow for a very bright and airy interior

Exterior: also pure white marble, with only a touch of color in the terracotta inserts around the windows and the entrance arch

Sinan referred to the Şehzade Camii as the “Masterpiece of his Apprenticeship,” but was unhappy - four massive piers interrupted the open space of the prayer hall

Süleymaniye Camii, (Mosque of Suleyman the Magnificent), Istanbul (Constantinople), 1550-57

Sinan’s “Masterpiece of his Maturity” was the mosque complex that Süleyman built to house his own tomb

Original complex: mosque itself, a hospital, primary school, public baths, a Caravanserai, four madrasa, a specialized school for the learning of hadith, a medical college, and a public kitchen that served food to the poor

Plan is Sinan’s closest imitation of Hagia Sophia – he uses only the two axial semi-domes, which form a line leading to the mihrab niche

If we were to cut off the courtyard, the plan would be almost identical

The resulting profile of the mosque is a perfectly balance concoction of domes, semi-domes, turrets, and buttresses (my 15-scoop ice cream sundae)

Almost exactly the same size a Hagia Sophia – the 37-meter dome is only one foot smaller than the dome in the Byzantine church, and the height of the mosque is also nearly the same

Courtyard: Sinan raises the three center arches very slightly to emphasize the main entrance

View of the exterior – noted the aa-b-aaa-b-aa arrangement of the arches – like syncopated music

Sinan also introduced the “pencil” minaret: tall, thin, with a sharp peaked roof

Sinan varies the size of the pointed arches in the gallery, with an a-b-a plan, instead of using a row of identical arches (like the Hagia Sophia); other than that, the effect is nearly identical

The end result is an interior that is more classically balanced than Şehzade Camii

Bulk of ornamentation is situated around mihrab, where Sinan has allowed the use of Iznik ceramics

Stained glass windows are placed on either side of the mihrab – but all the other windows in the mosque are of plain white glass to allow the max. amount of light into the space

Uses spolia from ruined Byzantine churches

This was ordered by Süleyman himself, who saw the Ottoman sultans as the legitimate successors to the Byzantine emperors

The closeness of the plan to that of Hagia Sophia is also directly related to this imperial self-promotion

Although older columns were used as spolia, Sinan did not allow any antique column capitals to be used in his mosques

Instead, he devises a blend of Turkish triangles and muqarnas to decorate the tops of the Byzantine spolia

Rüstem Paşa Camii (Mosque of the Grand Vizier Rüstem Paşa), Istanbul (Constantinople), 1561-62

Plan shows space issues – courtyard wraps around the mosque to make a side entrance, because it sits on the 2nd floor of the building structure

Built there b/c there was no land available

You must go through a small portal in the street and up a flight of stairs to get to mosque

Continuing to play w/ canopy dome issue, Sinan decides to place the dome at Rüstem Paşa Camii on eight supports – 4 are incorporated into walls, and 4 act as columns to delineate the center space from the side aisles

The interior is much busier than at Süleymaniye

This is due in part to the fact that Rüstem Paşa was fabulously wealthy and bought entire loads of Iznik tiles to decorate his mosque

Not as “classical” as his other mosques, but Rüstem is a popular tourist attraction b/c of its “jewel box” quality

Scale is much smaller, and the 8-sided canopy gives a very regular, almost monotonous repeat of the arched shapes

Ceramics are on the exterior porch as well as inside – you can see the patchwork quality of the decoration, where the areas around the central panel were filled with tiles left over from other designs

Some ex. of ceramics at Rüstem show the addition of the tomato red color previously unknown in Ottoman tile work

Selimiye Camii (Mosque of Selim II), Edirne (Hadrianople, Turkey), 1568-75

Sinan’s last major commission - “Masterpiece of his Old Age”

Largest of his mosques, built in Edirne, Süleyman’s son, Selim the Sot

There was more room to build in the smaller town

Plan is an enlargement and refinement of Rüstem Paşa, with the dome resting on eight supports

Supports are more clearly defined in this, and the monumental courtyard w/ its fountain has been retained from earlier Ottoman archit.

Directly in front of the mosque, Sinan also built a bazaar that demonstrates his love of simple, refined forms

Exterior of the Selimiye uses the same local stone – warm, yellow limestone with terracotta accents, that early Ottoman Edirne mosques used (Üç Şerefeli)

We see some very faint echoes of Western Renaissance archit. in his decorative program

Pishtaq corresponds to one of Palladio’s solutions for his entrance portals, but Islamicized

Entrance into mosque is pure Islam – a muqarnas arch carved white marble

Size of Selimiye allowed Sinan to double the arched elements in his side walls, so that two sets of windows could be inserted

Octagonal plan allowed Sinan to retain equally sized arches around perimeter of dome (all painted decoration is later)

Over the mihrab niche, you have a semi-dome, then above it a semi-circle of windows

Each side: Sinan had reversed the order, w/ semi-domes ABOVE the windows

Continues this through entire building to create another a-b-a-b rhythm

3 sides of the mosque that don’t have the mihrab have a monumental arch instead of the mini dome

Huge piers that support the dome:

Right one → incorporated into the wall, as it forms a frame for the mihrab niche

Left one → cut through, w/ a passage behind it, in order to lighten the heaviness of huge mass of stone

“Engaged” pier – it reconnects to the wall at the level of the gallery, so it operates as a kind of Π support

Costanzo da Ferrara, Portrait Medal of Mehmet II, Istanbul, Turkey, 1470’s

The Duke of Ferrara also sent his best medal sculptor, Costanzo, who created this portrait medal of Mehmet shortly before he died

Medallions were popular diplomatic gifts, as multiple copies could be cast

Large-Pattern Holbein Carpet, Anatolia, Turkey, late 15th century

Turkish rugs were prized by anyone in the West who had the money to buy one

Turkish carpets generally used abstract geometric patterns, which were laid out in medallions in the center of ornate geometric borders

This type of carpet, with the large central medallions, became known as the Holbein style

Sünnet Odası, Topkapı Sarayı (Circumcision Room, Topkapi Palace), Istanbul, Turkey, 1527-28

The other craft at which Ottoman artisans excelled was the ceramic tile

The original artists came from Tabriz, in Iran, and they trained local craftsmen

By the mid-16th century the ceramic workshops in Iznik (ancient Nicaea) were among the best

Under-glazed fritware (the artists were trying to imitate Chinese imports)

Underglaze-painted dish, Iznik (Nicaea, Turkey), c. 1550

Damascus Ware (turquoise, blues, and greens, always floral/organic motifs)

The long-curved leaves in this design form a style known as Saz

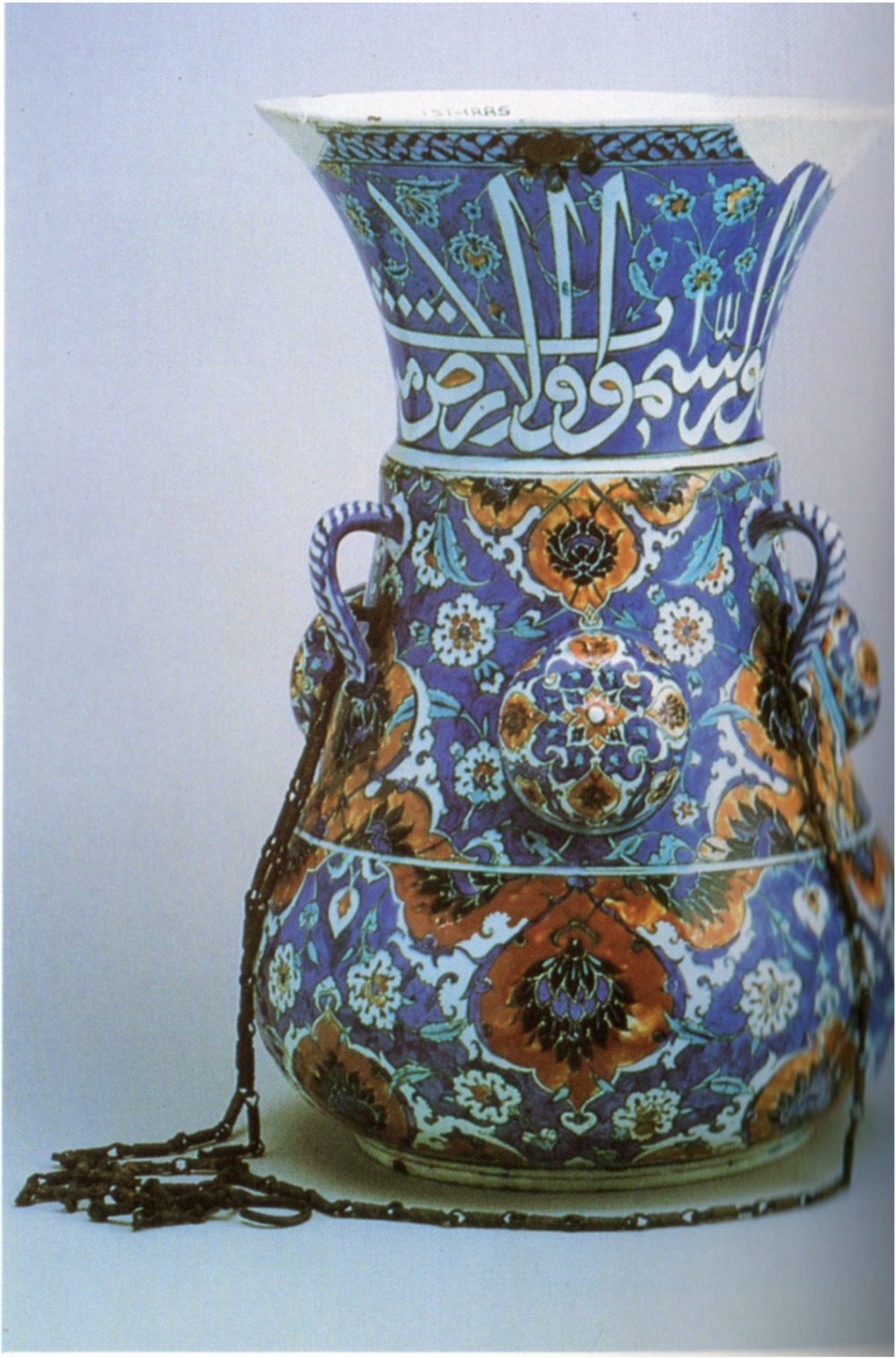

Underglaze-painted Mosque Lamp, Iznik, Turkey, c. 1557

Polychrome Ware

Invented in the 1550’s, when ceramic artists developed a new color - Red Bole (a tomato red under-glaze) to add to the existing colors

Purple, which occasionally appeared in Damascus ware, disappeared altogether.

Arifi, The Accession of Süleyman from Sulaymannama, Istanbul, Turkey, 1558

By the time of Süleyman, in the mid 16th-century, large numbers of high-quality manuscripts were being produced

More than anywhere else, these books tended to be histories – either of the world, or of the sultan in power at that time

The Sulaymannama (History of Süleyman) tells the history of the great sultan - but was composed 20 years before his death

This two-page scene shows his accession to the throne – which takes place when he receives the homage of all his advisors, the paşas and viziers

Close copy of Bihzad’s style