Chapter 7 - THE EXCRETORY SYSTEM REMOVES WASTE PRODUCTS

1/32

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

33 Terms

THE ORGANS THAT PROCESS AND REMOVE WASTES

Several organs in the body are involved either in the processing of wastes or in the excretion of those wastes.

• The lungs are involved in the excretion of the carbon dioxide that is produced by all body cells during cellular respiration. The removal of carbon dioxide by the lungs was discussed in Chapter 4.

• The liver has an important role in processing many substances so that they can be excreted.

• Sweat glands in the skin secrete sweat, which is largely water, for cooling. Sweat contains by-products of metabolism such as salts, urea and lactic acid.

• The alimentary canal passes out bile pigments, which enter the small intestine with the bile. These pigments are the breakdown products of haemoglobin from red blood cells.

• The kidneys are the principal excretory organs. They are responsible for maintaining the constant concentration of materials in the body fluids. The most toxic wastes removed by the kidneys are the nitrogenous wastes urea, uric acid and creatinine. Urea is produced in the liver from the breakdown of amino acids, which come from protein metabolism.

involved in processing and excreting wastes.

The kidneys, liver, lungs, sweat glands and alimentary canal are all involved in processing and excreting wastes.

The liver

The liver is located in the upper abdominal cavity. It is a very large organ with a host of different functions, one of which is the preparation of materials for excretion.

Proteins

The proteins, which have been built up from amino acids, become the primary constituents of cell structures, enzymes, antibodies and many glandular secretions. However, if other energy sources have been used up, the body is able to metabolise large amounts of proteins, breaking them down to produce energy. To make use of proteins in this way, the amino group (NH2 ) must first be removed from the amino acids. This process, called deamination, occurs in the liver with the aid of enzymes. Once the amino group has been removed, it is converted by the liver cells to ammonia (NH3) and then finally to urea. The urea is eliminated from the body in urine. The remaining part of the amino acid, which is primarily made up of carbon and hydrogen, is converted into a carbohydrate. This carbohydrate can be readily broken down by the cells to release energy, carbon dioxide and water.

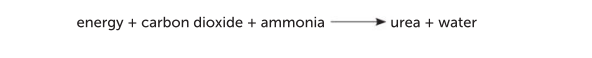

Deamination can be summarised as an equation:

Ammonia

is extremely soluble in water and is highly toxic to cells. One-thousandth of a milligram of ammonia in a litre of blood is sufficient to kill a person. The cells of the liver rapidly convert ammonia to the less toxic molecule urea. Moderate amounts of urea are harmless to the body. It is easily excreted by the kidneys and is eliminated from the body in the urine. Small amounts of urea are also lost in sweat from the sweat glands. The process can be expressed as:

The liver also:

• detoxifies alcohol and many other drugs such as antibiotics

• deactivates many hormones and converts them into a form that can be excreted by the kidneys

• breaks down haemoglobin from dead red blood cells to produce bile pigments, which are then passed out of the body with the faeces.

The liver plays an important role

The liver plays an important role in processing chemicals into a safer form. For example, it converts ammonia produced from proteins into the safer form of urea.

The skin

The main functions of the skin are to provide a protective covering over the surface of the body and to regulate body temperature. However, skin also has an important role in excretion. Even when there is no visible perspiration on the skin, the sweat glands secrete about 500 mL of water per day. Dissolved in the water are sodium chloride, lactic acid and urea. These substances are being excreted from the body. Some drugs, such as salicylic acid, are also excreted by the skin. Sweat glands are located in the lower layers of the skin. A duct carries the sweat to a hair follicle or to the skin surface where it opens at a pore. Cells surrounding the glands are able to contract and squeeze the sweat to the skin surface.

THE KIDNEYS

The kidneys are a pair of reddish-brown organs located in the abdomen. Each kidney is approximately 11 cm long. Their position and relative size can be seen in Figure 7.6. The kidneys, the bladder and their associated ducts are often referred to as the urinary system. The kidney is enclosed by the renal capsule. Under this is the outer renal cortex, the inner renal medulla, and then the renal pelvis sits in the concave side of the kidney. The renal hilum lies on the concave surface of the kidney, and is where the vessels enter and leave. The medulla consists of a number of renal pyramids, which are separated by renal columns, where the blood vessels lie.

what is a nephron

The nephron is the microscopic, functional unit of the kidney

The structure of nephrons

When examined under a microscope, the kidney is seen to be composed of a large number of structures called nephrons and collecting ducts. The nephron is the functional unit of the kidney, as it is where the urine is formed.

Each nephron consists of

Each nephron consists of a renal corpuscle and a renal tubule. The renal corpuscle consists of the glomerulus and the glomerular capsule. The glomerular capsule (formerly known as the Bowman’s capsule) is the expanded end of the nephron. It looks like a double-walled cup that surrounds, and almost completely encloses, a knot of arterial capillaries called the glomerulus.

Leading away from the glomerular capsule is the

renal tubule, a tube about 5 cm long. It begins with a winding, or convoluted, section called the proximal convoluted tubule. Beyond this, each tubule has a straight portion before it forms a loop, the loop of Henle. The loop of Henle is like a hairpin bend, with a straight section leading into the bend and another straight section leading away from the bend. The tubule then becomes convoluted and highly coiled again. This second coiled section is known as the distal convoluted tubule. The distal convoluted tubules of several nephrons join into a collecting duct that opens into a chamber in the kidney called the renal pelvis. The renal pelvis is shaped like a funnel and channels fluid from the collecting ducts into the ureter.

renal arteries.

Blood enters the kidney through the renal arteries. These arteries are quite large, so together the two kidneys receive about a quarter of the blood from the heart. Approximately 1.2 L of blood pass through the two kidneys every minute. Shortly after entering the kidney, the renal artery divides into small arteries and arterioles. Each renal corpuscle is supplied by an arteriole, the afferent arteriole, which then forms a knot of capillaries called the glomerulus. This knot of capillaries is located within the glomerular capsule. The capillaries eventually unite to form another arteriole, the efferent arteriole, which passes out of the renal corpuscle. After leaving the renal corpuscle, the efferent arteriole breaks up into a second capillary network. These capillaries surround the proximal and distal convoluted tubules of the nephron, the ascending and descending limbs of the loop of Henle, and the collecting duct. They are known as peritubular capillaries (Figure 7.7). Venous blood drains away from this network of capillaries and eventually leaves the kidney in the renal vein.

Key concept Blood enters

Blood enters the nephron through the afferent arteriole. It is filtered in the glomerulus, a network of capillaries, and then exits via the efferent arteriole.

The production of urine

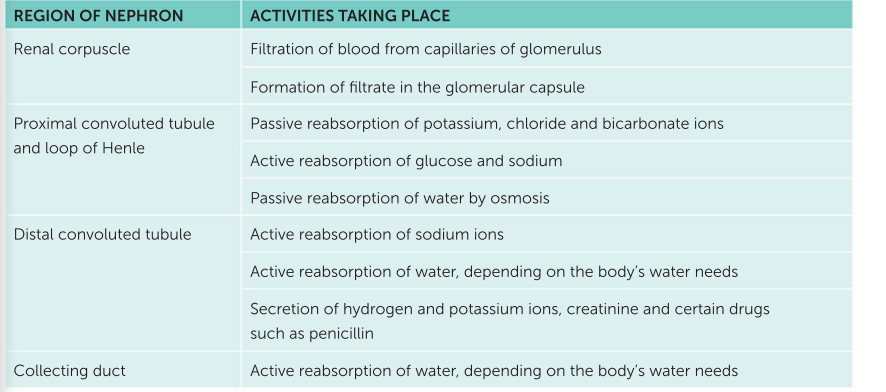

The formation of urine by the nephrons of the kidneys involves three major processes: glomerular filtration, selective reabsorption and secretion by the tubules.

Glomerular filtration

The first step in the production of urine is glomerular filtration. This process takes place in the renal corpuscle when fluid is forced out of the blood and is collected by the glomerular capsule. Fluid is normally forced out of the capillaries into the tissue in all parts of the body due to differences in pressure between the capillaries and tissue. In the glomerulus the process is enhanced by the high pressure of blood. The afferent arteriole leading into the glomerulus has a wider diameter than the efferent arteriole leaving it. This narrowing of the efferent arteriole increases resistance to the flow of blood and produces a higher pressure in the glomerulus. The blood in the capillaries in the glomerulus is separated from the cavity of the capsule by only two single layers of thin, flat cells. One layer makes up the capillary wall and the other the wall of the capsule. Therefore, when blood enters the glomerulus, the high pressure forces water and dissolved blood components through the differentially permeable cell membranes and into the capsule. The resultant fluid is termed the filtrate. In a healthy person, the filtrate consists of all the materials present in the blood except red and white blood cells and plasma proteins. These are too large to pass through the differentially permeable membranes of the cells making up the walls of the glomerulus and capsule. Therefore, the filtrate consists of water, salts, amino acids, fatty acids, glucose, urea, uric acid, creatinine, hormones, toxins and various ions. As blood flows through the capillaries of the glomerulus, 20% of the plasma is filtered through the capillary walls into the glomerular capsule. Complete filtration of all the plasma cannot take place as the blood in the capillaries is continually being pushed on by the blood behind it. With about 1.2 million nephrons in each kidney, the amount of plasma filtered every minute is still quite high. In normal adults, the total filtrate produced by all the renal corpuscles of both kidneys is about 125 mL of filtrate per minute. This amounts to about 180 L in a day! Although this large amount is filtered, only about 1% actually leaves the body as urine. Most is reabsorbed back into the blood.

Reabsorption

Many of the components of the plasma that are filtered from the capillaries of the glomerulus are of use to the body, and their excretion would be undesirable. Therefore, some selective reabsorption of the filtrate must take place, returning them to the blood in the peritubular capillaries. These processes are carried out by the cells that line the renal tubule. Materials that are reabsorbed include water, glucose and amino acids. Ions such as sodium, potassium, calcium, chloride and bicarbonate are also reabsorbed. Some wastes, such as urea, are partially reabsorbed as well. Like the body’s other exchange surfaces, a large surface area is required. This large surface area for effective reabsorption of materials is achieved by the long length of the kidney tubule – two sets of convolutions and the long loop of Henle – and by the huge number of nephrons in each kidney. Reabsorption of much of the water in the filtrate can be regulated. Depending on the body’s water requirements, the permeability of the plasma membranes of the cells making up parts of the tubules can be changed. Therefore, more or less water can be reabsorbed depending on the body’s requirements. This is an active process, under hormonal control, and is often referred to as facultative reabsorption. This is discussed further in Unit 3.

Tubular secretion

The third process involved in the formation of urine is tubular secretion. Whereas selective reabsorption removes substances from the filtrate into the blood, tubular secretion adds materials to the filtrate from the blood, as Figure 7.10 shows. Materials secreted in this way include potassium and hydrogen ions, creatinine, and drugs such as penicillin. Tubular secretion can be either active or passive, and has two main effects.

• It maintains the blood pH. The body needs to maintain the blood within its normal pH range of 7.4–7.5. Our diets usually contain many acid-producing foods that tend to lower pH; therefore, the kidneys must remove the excess hydrogen and ammonium ions.

• It maintains the urine pH. The presence of hydrogen and ammonium ions in the urine makes the urine slightly acidic, with a normal pH of 6.

Water and other substances not reabsorbed drain from the collecting ducts into the renal pelvis. From the pelvis, the urine, as it is now called, drains into the ureters and is pushed by waves of muscle contraction to the urinary bladder where it is stored. The two ureters, one from each kidney, are essentially extensions of the pelvis of the kidneys. They extend 25–30 cm to the urinary bladder. The bladder is a hollow muscular organ from which the urethra exits. The urethra carries urine from the bladder to the exterior of the body.

The processes of glomerular filtration, selective reabsorption and tubular secretion control the composition of urine and, therefore, the blood.

The formation of urine is maximised by the structure of the kidney, particularly the nephron, as follows:

• The glomerular capsule surrounds the glomerulus to collect the fluid filtered out of the blood capillaries. • There are only two cells for the filtrate to pass through from the blood, one cell from the capillary wall and the other from the capsule wall.

• A large volume of blood passes through each kidney. The continual flow maintains the concentration gradient. • The efferent arteriole leading out of the glomerulus has a smaller diameter than the afferent arteriole leading in. This raises the blood pressure so that more fluid is filtered out of the blood. • Each tubule has a large surface area for reabsorption and secretion due to each tubule having two sets of convolutions and a long loop. • Each kidney has over a million nephrons, so the total surface area available for reabsorption and secretion is extremely large.

The composition of urine

The body must excrete its waste products, such as urea, sulfates and phosphates, on a regular basis. These substances need to be in solution, and so the elimination of these wastes requires a certain amount of water loss. Regardless of the amount of water available in the body, or the amount taken in, about half a litre of water must be lost each day simply to remove wastes. When the water content of the body fluids is low, the urine that is excreted is very concentrated. Table 7.2 compares the composition of the fluid filtered from the blood and the urine. It also shows the amount of each component that is reabsorbed during a 24-hour period. The values shown can vary markedly between individuals, and with diet, and so they should be regarded only as a guide. Uric acid is produced by the metabolism of substances called purines. Purines may come from the breakdown of nucleic acids, such as DNA, when cells die. Purines also occur naturally in many foods. Creatinine is produced in muscle from the breakdown of creatine phosphate, an energy-rich molecule. Thus, under normal circumstances: • about 99% of the water that enters the nephron is reabsorbed • the urine does not normally contain significant amounts of protein • the urine does not normally contain any glucose • the main materials making up the urine, besides water, are urea, ions, uric acid and creatinine. Generally, a healthy adult produces about 1.5 L of urine a day, but this varies tremendously depending on diet, environment and other factors. Table 7.3 indicates the components that the urine of a healthy adult may contain. Again, this is highly variable and should be used only as a guide. The amber colour of urine is due to the presence of some bile pigments.

Dialysis

Dialysis is a method of removing wastes from the blood when kidney failure occurs. There are two types of dialysis: peritoneal dialysis and haemodialysis. The peritoneum is a membrane that lines the inside of the abdominal cavity and covers abdominal organs such as the stomach, liver and intestines. It has a very rich blood supply. Peritoneal dialysis occurs inside the body using the peritoneum as a membrane across which waste can be removed. A tube, called a catheter, is placed through the wall of the abdomen. For an adult, 2–3 L of fluid are passed through the catheter into the abdominal cavity. The fluid contains glucose and other substances at concentrations similar to those found in the blood. However, there are no wastes in the fluid. This means that, because of the concentration difference, wastes will diffuse out of the blood into the fluid in the abdominal cavity. Useful substances stay in the blood because there is no concentration difference between the blood and the fluid. After a time, the fluid that was placed in the abdominal cavity is drained out through the catheter, along with any wastes and extra water that have diffused from the blood. Peritoneal dialysis is usually done each day.