trauma biomechanics, BFT

1/43

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

44 Terms

slow impact trauma

in kilometers per hour (kmh), can include beatings, motor vehicle accidents, falls from heights, airplane crashes — recording of location, appearance, morphological attributes of fractures are necessary, may provide interpretive clues to speed, direction of load

force (/load)

any mechanical disturbance that causes an object to deform, change its state of motion,/both

magnitude

area of force being applied

direction

line along which magnitude of load travels

stress

force per unit of area

strain

relative deformation

slow loaded force

permits bone to respond, compensate for an increase in stress; when stress is removed, bone may; return to its original shape, remain deformed, fail — in rapid loading scenarios, bone dont experience bending/adjustment; it merely shatters due to energy absorbance

ante-mortem

before death

peri-mortem

at/around time of death

post-mortem

after death

wet bone

can pass through both elastic, plastic phases before failure

dry bone

if stress exceeds strain, dry bone fractures immediately; dry bone may resist stress to higher lvl, but failure occurs immediately at end of elastic phase, no elastic/plastic deformation of dry bone

postmortem fracture

Bone damage occurring after death, often from drying or environmental exposure. These fractures appear dry, follow the bone's grain, may show color differences, and include cortical flaking and mosaic-like cracking

ante- vs peri-mortem

Antemortem fractures show healing signs like porosity, edge rounding, and callus formation—indicating the injury happened before death. Perimortem fractures lack healing but occurred around the time of death when bones were still fresh and flexible

fracture healing

Healing time depends on bone type, fracture severity, immobilization, blood supply, infection, and the individual’s age

peri- vs post-mortem

Perimortem fractures occur when bone is still fresh (wet), showing angled breaks with sharp or smooth edges. Postmortem damage happens after death, often showing right-angle fractures with flat, dry edges. Timing is easier to determine in fresh remains than in skeletonized ones

fracture margin

Perimortem (green bone) fractures have smooth, sharp, bevelled edges matching bone color, sometimes with flaking. Postmortem (dry bone) fractures have jagged, blunt edges that are lighter in color due to environmental exposure

BFT

a common injury causing abrasions, contusions, lacerations, or fractures. It may result from a single fatal event or repeated trauma with healing, possibly indicating abuse. Injury severity depends on impact surface size and bone resistance—smaller contact areas (like on the curved skull) focus energy and cause more damage

classification of fractures

Fractures are first categorized as simple (2 pieces) or multi-fragmented/comminuted (3+ pieces), and then by shape (e.g. spiral, linear), location, completeness, and orientation. A complete break separates the bone; an infarction is an incomplete break

types of fractures

Radiating: Spread outward from the impact point; common in gunshot or sharp force trauma.

Linear: Run along the bone's axis.

Transverse: Cross the bone's axis.

Concentric (Hoop): Circle around the impact site; often seen in depressed fractures.

Radiating and concentric types are typical in high-stress trauma.

traverse

linear

oblique non-displaced

oblique displaced

spiral

greenstick

comminuted

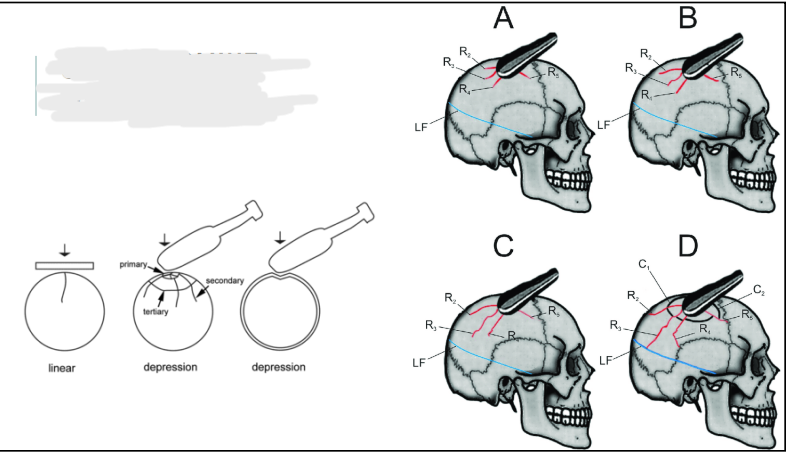

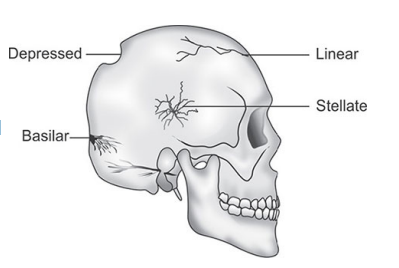

cranial vault fractures

Classified by shape:

Linear (70–80%): Straight cracks across the skull.

Diastatic (5%): Follow and separate sutures.

Other types (15%):

Depressed – bone pushed inward

Comminuted – multiple fragments

Stellate – star-shaped fracture pattern

cranial BFT

Fractures follow paths of least resistance, avoiding strong buttresses like the frontal midline, petrous temporal, and mastoid. Instead, they often travel through thinner bone areas, adjacent orbits, or along sutures—natural weak points in the skull

sequence of events

Fractures follow paths of least resistance. The first impact creates radiating fractures spreading until energy dissipates, often with concentric fractures. A second impact produces intersecting fracture lines, helping determine the order of blows.

linear vault fractures

These fractures pass through the cranial vault’s outer and/or inner layers, following paths of least resistance. They’re often curved, caused by large-mass forces like blunt objects or accidents. Linear fractures can also result from force transmitted through the body, causing breaks distant from the impact site

depressed cranial fractures (complete)

These fractures cause inward crushing or penetration of the skull, collapsing the diploe and breaking the inner and outer tables. Radiating linear fractures often extend from the impact site. The damage usually outlines the impacting object, though skull curvature can sometimes limit the imprint size

stellate, comminuted

Stellate fractures are star-shaped with multiple radiating cracks from a heavy, low-velocity impact, often on upper parietals and sometimes with depressed fractures.

Comminuted fractures involve bone fragmentation from heavy, low-speed crushing forces, usually on skull convexities, making full reconstruction nearly impossible.

BFT to long bones

classification of long bone fractures

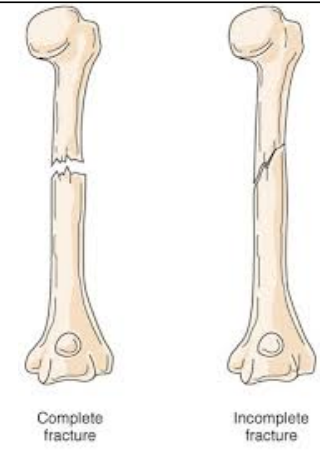

Fractures are classified by the degree and pattern of breakage into two main types:

Incomplete fractures (partial breaks)

Complete fractures (bone fully separated)

incomplete fractures

These fractures retain some bone continuity and are more common in children due to their more organic, moist bones. They become less frequent as bones dry out postmortem.

bow fractures (incomplete fracture)

Bone shows exaggerated curvature along its length, common in forearms and juveniles. The bone may plastically deform and remodel over time.

greenstick fracture (incomplete fracture)

Result from bending forces causing tension on one side and compression on the other. This creates an incomplete transverse fracture starting on the tension side and extending halfway through the bone

depressed fractures (incomplete fracture)

Occur mainly in the skull from direct blows causing inward “caving.” Injury severity depends on impact size and force velocity. Often only the outer table is damaged; sometimes the inner table shows incomplete fractures, especially with smaller, faster impacts

complete fractures

Fractures that fully separate bone into two or more pieces. They are further classified by the shape and location of the fracture line

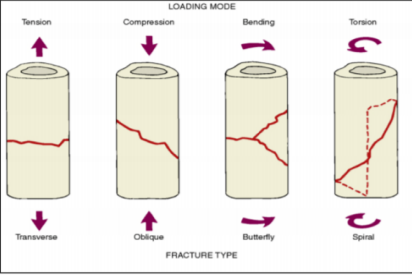

transverse fracture (complete fracture)

Runs roughly at right angles to the long axis of the bone.

Often caused by three-point bending forces during blunt force trauma.

Produces severe angulation and concentrated force.

May occur when the bone is supported longitudinally and not under normal compression.

oblique fracture (complete fracture)

Runs diagonally (around 45°) across the bone shaft.

Caused by a mix of bending and compressive forces.

Fracture propagation varies:

High compression → purely oblique fracture.

High bending → resembles transverse fracture.

Commonly starts as transverse, then extends obliquely due to shear forces.

Results in a fracture partly perpendicular, partly diagonal to the bone’s long axis.

spiral fracture (complete fracture)

Start as small cracks that spiral around the bone shaft, creating a vertical step.

Caused by rotational (torsional) forces, usually low-velocity.

The spiral direction reveals the twist’s direction and helps reconstruct the injury event

comminuted fracture (complete fracture)

Bone breaks into more than two fragments.

Classified as slight, moderate, or marked comminution based on fragment number and size.

Severe fragmentation indicates high-force impacts.