Mutation and Mutagenesis

1/28

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

29 Terms

mutations and mutagenesis

Define mutation, discriminate between DNA damage and mutation.

Classify the different kinds of mutations according to the DNA base that changes.

Explain the classification of mutations according to the immediate consequence in protein synthesis.

State how mutations may suppress other mutations.

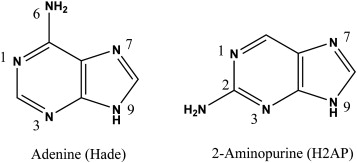

Recognize the tautomeric properties of the nitrogen bases.

Define and give examples of chemical mutagens.

State changes caused by chemical mutagens.

Explain physical mutagenesis, and mention some physical mutagens.

State changes caused by physical mutagens.

Describe the consequences of mutations, natural selection, and evolution.

Read the Ames (or Salmonella) test for carcinogenesis Discuss the principles involved in the Ames test.

Explain the Delaney Clause, and mention the arguments for and against it.

Define the GRAS list, and describe was it devised.

Review the attached handout below for this topic.

MUTATIONS

definition

is DNA damage mutations?

what are the reasons why most mutations have an absence of an effect?

what is the difference between degeneration and redundancy?

Definition of mutation: Alteration in DNA structure that leads to permanent change in genetic information. In order to establish itself, the mutation needs a round of DNA replication. “DNA damage” is not “mutations”, because it is fixed. Only a small proportion of damaged DNA goes on to become mutations. Moreover, most mutations have no noticeable effect.

DNA damage is not mutations because DNA damage is fixed.

The absence of an effect can be due to several reasons:

1) 3% of the DNA codes for genes, thus mutations have a big chance of not disturbing genes;

2) the genetic code is degenerated, so some codons can have a base (mainly the wobble base) changed and still code the same amino acid (silent mutations);

3) most proteins tolerate single amino acid substitutions without becoming pathological;

4) most mutations are somatic, so they are not inherited;

5) the cell has a certain degree of redundancy in its systems

Genetic code redundancy means that multiple different codons (3-letter mRNA sequences) can code for the same amino acid.

Types of Mutations

point mutation (transition, transversion)

tautomerization (keto, enol)

1.The most common is the point mutation. A point mutation is a change in a single nucleotide (one “letter”) in the DNA sequence. There are two types of point mutations:

transitions (substitute purine by purine or pyrimidine by pyrimidine) and transversions (substitutes a purine by a pyrimidine and vice versa).

A transition mutation is a change within the same class of nitrogenous base:

purine → purine (A ↔ G)

pyrimidine → pyrimidine (C ↔ T)

a transition is a “mild” or “small” shift—moving across within the same category

transversion: “a turning across”

A transversion mutation is a change between classes:

purine → pyrimidine

pyrimidine → purine

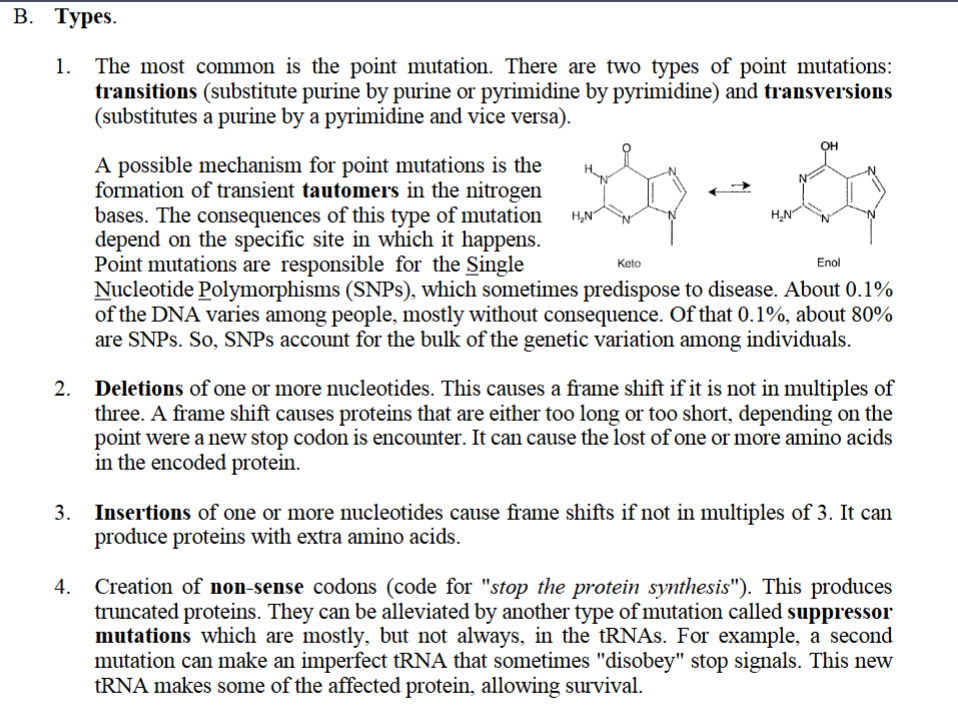

A possible mechanism for point mutations is the formation of transient tautomers in the nitrogen bases. The consequences of this type of mutation depend on the specific site in which it happens.

1. Nitrogenous bases can temporarily shift shape (tautomers)

DNA bases (A, T, G, C) normally exist in their common form, but sometimes they spontaneously shift into a rare alternative form called a tautomer.

Adenine (A) can switch to an imino form

Cytosine (C) can switch to an imino form

Guanine (G) and Thymine (T) can switch to an enol form

Keto form

Has a carbonyl group (C=O)

This is the more stable, more common form for DNA bases (like thymine and guanine).

Enol form

Has an OH group attached to a carbon–carbon double bond (C=C–OH)

This is a rare, unstable form

Keto ⇌ Enol

This reversible chemical shift is called tautomerization

2. A tautomer pairs incorrectly during DNA replication

Because the tautomer has a slightly different structure, it base-pairs wrong:

A* (rare form) pairs with C instead of T

C* pairs with A instead of G

G* pairs with T instead of C

T* pairs with G instead of A

So during replication, the DNA polymerase inserts the wrong nucleotide.

3. After replication, the mismatch becomes permanent

One daughter strand keeps the original correct base

The other daughter strand incorporates the incorrect base

After another round of replication, the incorrect base becomes locked in as a substitution mutation (transition or transversion).

This is how a simple tautomer shift → point mutation.

This creates a mismatched base pair → the first step of a point mutation.

These rare forms have different hydrogen-bonding patterns

what is the most common type of mutation?

point mutation

(point mutations)

SNP

SNP: condition where one nucleotide in the DNA sequence has many forms (polyMORPhism) across individuals

polymorphism: '“many forms”

Point mutations are responsible for the Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs), which sometimes predispose to disease. About 0.1% of the DNA varies among people, mostly without consequence. Of that 0.1%, about 80% are SNPs. So, SNPs account for the bulk of the genetic variation among individuals.

(types of point mutations)

deletions

2. Deletions of one or more nucleotides. Deletions causes a frame shift if it is not in multiples of three. A frame shift causes proteins that are either too long or too short, depending on the point were a new stop codon is encounter. a deletion mutation can cause the lost of one or more amino acids in the encoded protein.

(types of point mutations)

insertion

3. Insertions of one or more nucleotides cause frame shifts if not in multiples of 3. It can produce proteins with extra amino acids.

(point mutations)

non-sense codons

suppressor mutations

4. Creation of non-sense codons (code for "stop the protein synthesis"). This produces truncated proteins (shorted in duration or extent). Nonsense codons can be alleviated by another type of mutation called suppressor mutations which are mostly, but not always, in the tRNAs. For example, a second mutation can make an imperfect tRNA that sometimes "disobey" stop signals. This new tRNA makes some of the affected protein, allowing survival.

considered nonsense because a stop codon does not code for an amino acid, but rather codes for a stop codon.

A suppressor mutation must occur in tRNA to alleviate a nonsense mutation because tRNAs are the molecules that directly interpret codons during translation.

1. A nonsense mutation introduces a STOP codon

Example:

UAU (Tyr) → UAG (STOP)

The ribosome reaches UAG and terminates translation early, producing a truncated, nonfunctional protein.

2. Only tRNA can “override” a STOP codon

Why?

Because: tRNAs are what read codons on mRNA.

Each tRNA has an anticodon that pairs with a codon.

If a STOP codon is to be bypassed, something must pair with it instead of letting release factors bind.

Release factors usually bind to STOP codons and end translation.

A normal tRNA for tyrosine has anticodon:

AUA → pairs with UAU

A suppressor tRNA might mutate its anticodon to:

CUA → pairs with UAG (STOP)

Now the tRNA:

binds to the STOP codon

inserts an amino acid (like tyrosine)

lets translation continue downstream

This suppresses (overrides) the nonsense mutation.

II. MUTATIONS ARE VERY RARE

DNA pol III of E.coli

what is proofreading done by in mammals?

relationship between mutations and evolution

Approximately six nucleotides change per cell per year for an overall frequency of ~10-10.

A. DNA polymerase III of E. coli

DNA pol III proofreads the outcome of the last polymerization before proceeding. Ten percent of correctly matched nucleotides get excised. This means that the enzyme is very stringent, and "in doubt" it is slanted towards deletion of the nucleotides involved.

1. DNApol III is very big (800 kd) and has about 12 peptides.

2. In mammals, the proofreading is done by other peptides

3. Fidelity increases by the 3' → 5' nuclease activity. So, it can remove in “reverse”.

fidelity: how accurate an enyzme is doing its job.

4. Speed increases by the high processivity of the enzyme, i.e. it does not fall off

5. Initially, the enzyme has an error rate of 1/10,000 , but only 1/1000 errors remain, of these, 99.9% are corrected. Error correction is by polymerase and post-polymerase mechanisms

6. There is a balance between mutation rate and evolution. Almost all the mutations are detrimental, but you need mutations some in order to evolve. This is particularly true in environments that change quickly, for example the HIV virus under immunological attack.

relationship between mutations and evolution:

Mutations are the ultimate source of genetic variation, and genetic variation is necessary for evolution.

Without mutations:

No new alleles

No new traits

No adaptation

No evolution

So yes—mutation is essential for evolution.

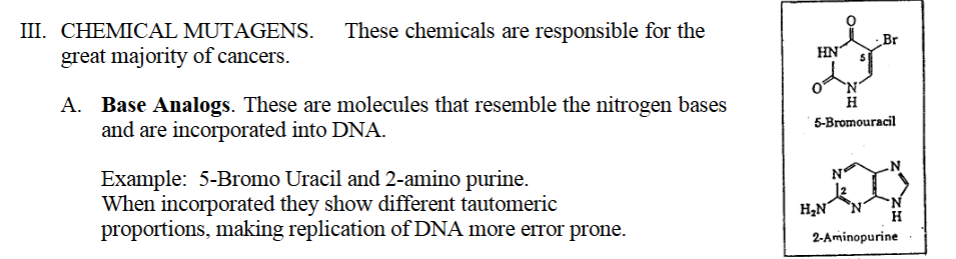

III. CHEMICAL MUTAGENS.

A chemical mutagen is: Any chemical substance that increases the rate of mutations by altering the DNA’s structure or interfering with DNA replication.

These chemicals are responsible for the great majority of cancers.

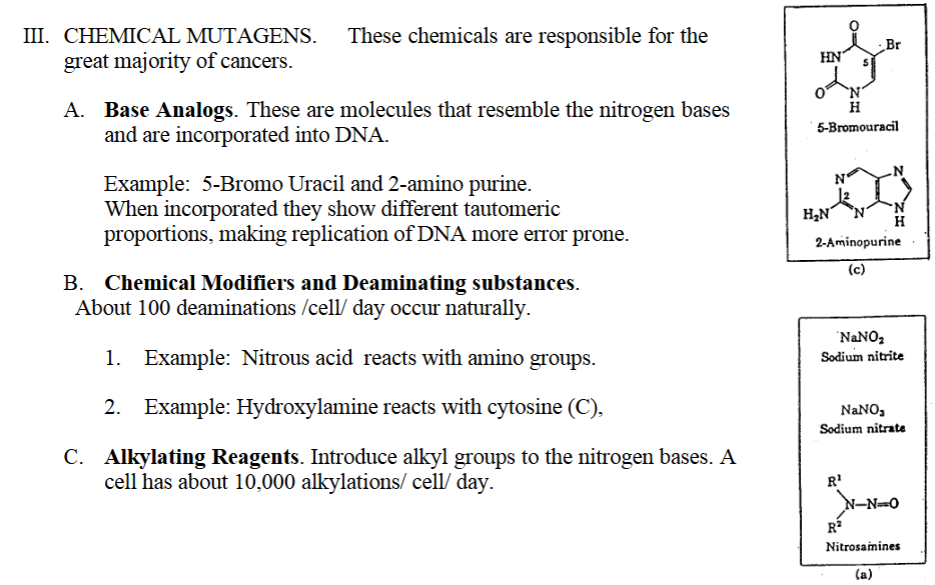

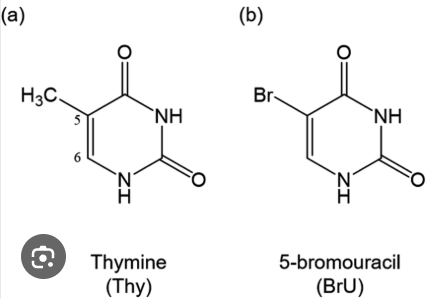

A. Base Analogs. These are molecules that resemble the nitrogen bases and are incorporated into DNA.

"base analog: molecules that are analogous to bases (by resemblance)

Example of a base analog: 5-Bromo Uracil and 2-amino purine.

2-amino purine is a base analog, it’s not a nitrogenous base.

When incorporated they show different tautomeric proportions, making replication of DNA more error prone

B. Chemical Modifiers and Deaminating substances. About 100 deaminations /cell/ day occur naturally.

1. Deamination = removing an amino group (–NH₂) from a nitrogenous base

Some bases in DNA contain an amino group.

A deaminating reaction removes the amino group, changing one base into another:

Cytosine → Uracil

These conversions can cause incorrect base pairing → mutations.

1. Example: Nitrous acid reacts with amino groups and deaminates the base.

2. “Chemical modifiers” refers to chemicals that alter DNA

Certain chemicals modify bases by adding or removing chemical groups.

Hydroxylamine (NH₂OH) is another chemical mutagen, but it is very specific.

It reacts almost only with cytosine.

It adds a chemical group to C, causing it to mispair with adenine (A).

This causes:

C→T transitions

(because C pairs with A instead of G)

C. Alkylating Reagents. chemicals that add alkyl groups to the nitrogen bases. A cell has about 10,000 alkylations/ cell/ day.

1. Example: Dimethyl sulfate (DMS) and Ethyl methane sulfonate (EMS) are alkylate guanine. Releases the nitrogen base from guanine which weakens the bond between guanine and DNA leaves a hole in DNA that can be filled with any other base.

When DNA is replicated:

Any base (A, T, G, C) can be inserted randomly

→ very high mutation rate

2. Example: Nitrogen mustards like β-chloroethylamine.

3. Example: Benzopyrene is oxidized to a reactive molecule that attaches itself to Guanine.

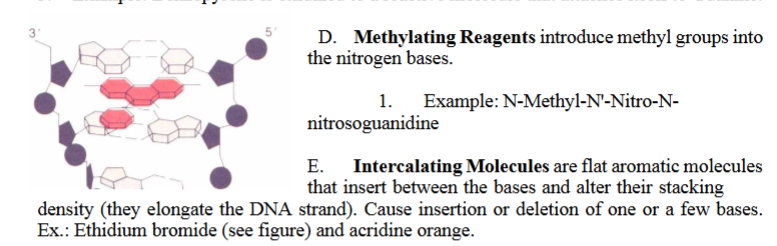

D. Methylating Reagents introduce methyl groups into the nitrogen bases.

1. Example: N-Methyl-N'-Nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine

When a base receives a methyl group, its hydrogen-bonding pattern changes.

So methylation can cause wrong base pairing → point mutations.

Sometimes methylation destabilizes the base–sugar bond, causing the base to fall off, creating an abasic site (AP site).

This leaves a hole in the DNA.

During replication, the polymerase inserts any random base, causing mutations.

E. Intercalating Molecules are flat aromatic molecules that insert between the bases and alter their stacking density (they elongate the DNA strand). Cause insertion or deletion of one or a few bases.

Ex.: Ethidium bromide (see figure) and acridine orange.

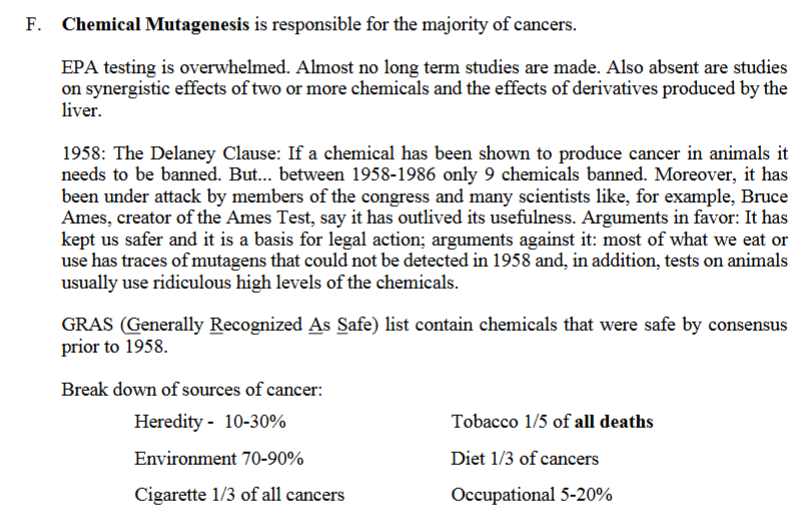

F. Chemical Mutagenesis is responsible for the majority of cancers

1. Base Analogs (5-bromouracil, 2-aminopurine)

what does base does 5-bromouracil look like? therefore, what base does 5-bromouracil bind to?

what does base does 2-aminopurine look like? therefore, what base does 2-aminopurine bind do?

1. Base Analogs (5-bromouracil, 2-aminopurine) WHY they cause mutations

Base analogs look like normal bases, so DNA polymerase mistakenly incorporates them into DNA.

But—they have abnormal tautomeric forms and abnormal pairing behavior, so they mispair.

Examples

5-bromouracil looks like thymine (both are pyramidines) → 5-bromouracil pairs with A

But in rare form pairs with G

→ causes T ↔ C transitions2-aminopurine looks like adenine (both are purines)

Can pair with T or C

→ causes A ↔ G transitions

Base analogs get inserted normally but pair incorrectly→ mispairing → point mutations.

Chemical Modifiers (Hydroxylamine)

2. Chemical Modifiers (Hydroxylamine) WHY they cause mutations

Chemical modifiers attach functional groups to specific bases, altering hydrogen-bonding.

Hydroxylamine reacts specifically with cytosine

Modified C pairs with A instead of G

→ C → T transitions

They chemically modify bases so the base-pairing rules change.

Deaminating Agents (Nitrous acid)

deaminating agents remove amino groups (–NH₂) from bases → converting one base into a different base.

C → U

(U pairs with A) → C→T transitionA → hypoxanthine

(pairs with C) → A→G transition

Deamination literally changes one base into another → mispairing during replication.

Nitrous acid produces NO⁺ nitrosating agents

These attack –NH₂ groups on DNA bases

Converts amino groups → keto groups

Changes the identity and base-pairing of A, C, and G

Causes transition mutations (A→G, C→T)

Alkylating Agents (DMS, EMS)

alkyl group

weakened glycosidic bond

abasic site in DNA

4. Alkylating Agents (DMS, EMS) WHY they cause mutations

They add alkyl groups (–CH₃, –C₂H₅) to bases, which:

A. Change base-pairing

O⁶-ethylguanine pairs with T instead of C

→ G→A transition

B. Cause base loss

1⃣ Alkylation adds a positive charge at N7 (especially in guanine)

2⃣ Why does a positive charge weaken the glycosidic bond? (charge repulsion with sugar, distortion of ring structure, leaving group becomes better)

Alkylation weakens the glycosidic bond → base falls off → abasic site.

During replication, polymerase inserts any base randomly → mutation.

Bottom line: Alkyl groups distort the base so it pairs wrong, or knocks it out entirely.

5. Methylating Agents

(e.g., N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine)

guanine

blocks replication

5. Methylating Agents

(e.g., N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine)

WHY they cause mutations

They add methyl groups specifically to bases (especially guanine).

Results:

O⁶-methylguanine pairs with T → G→A transitions

3-methyladenine blocks replication forks → strand breaks

Bottom line: Methylation alters pairing or physically blocks replication.

(Chemical Mutagens)

Intercalating Molecules (Ethidium bromide)

why do intercalating molecules cause frameshift mutations?

6. Intercalating Molecules (Ethidium bromide) WHY they cause mutations

Intercalating agents are flat, aromatic molecules that slide between base pairs.

pushes bases apart

distorts the helix

confuses DNA polymerase during replication

The polymerase may insert or delete a nucleotide to adjust to the distortion.

→ Causes frameshift mutations (insertions/deletions)

Bottom line: Intercalators wedge into DNA → replication slippage → frameshifts.

(chemical mutagens)

base analogs

A. Base Analogs. These are molecules that resemble the nitrogen bases

and are incorporated into DNA.

Example: 5-Bromo Uracil and 2-amino purine.

When incorporated they show different tautomeric

proportions, making replication of DNA more error prone.

Chemical Modifiers and Deaminating substances

nitrous acid

hydroxyamine

B. Chemical Modifiers and Deaminating substances.

About 100 deaminations /cell/ day occur naturally.

1. Example: Nitrous acid reacts with amino groups.

2. Example: Hydroxylamine reacts with cytosine (C)

alkylating agents

DMS, EMS

nitrogen mustards B-chloroethylamine)

benzopyrene

C. Alkylating Reagents. Introduce alkyl groups to the nitrogen bases. A

cell has about 10,000 alkylations/ cell/ day.

1. Example: Dimethyl sulfate (DMS) and Ethyl methane sulfonate (EMS) are specific for guanine. Releases the nitrogen base, leaves a hole that can be filled with any other base.

2. Example: Nitrogen mustards like β-chloroethylamine.

3. Example: Benzopyrene is oxidized to a reactive molecule that attaches itself to Guanine

methylating agents

N-Methyl-N'-Nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine

D. Methylating Reagents introduce methyl groups into

the nitrogen bases.

1. Example: N-Methyl-N'-Nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine

attaches to guanine

intercalating molecules (Ethidium bromide) (acridine orange)

E. Intercalating Molecules are flat aromatic molecules that insert between the bases and alter their stacking density (they elongate the DNA strand). Cause insertion or deletion of one or a few bases.

Ex.: Ethidium bromide (see figure) and acridine orange

chemical mutagenesis

the delaney cause

arguments in favor of delaney cause

arguments against delaney cause

GRAS

F. Chemical Mutagenesis is responsible for the majority of cancers.

EPA testing is overwhelmed. Almost no long term studies are made. Also absent are studies on synergistic effects of two or more chemicals and the effects of derivatives produced by the liver.

delaney cause: “The legal rule written by (or attributed to) Congressman Delaney.

1958: The Delaney Clause: If a chemical has been shown to produce cancer in animals it needs to be banned. But... between 1958-1986 only 9 chemicals banned. Moreover, it has been under attack by members of the congress and many scientists like, for example, Bruce Ames, creator of the Ames Test, say it has outlived its usefulness.

Arguments in favor: It has kept us safer and it is a basis for legal action;

arguments against it: most of what we eat or use has traces of mutagens that could not be detected in 1958 and, in addition, tests on animals usually use ridiculous high levels of the chemicals.

GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe) list contain chemicals that were safe by consensus prior to 1958.

Break down of sources of cancer:

Heredity - 10-30%

Tobacco 1/5 of all deaths

Environment 70-90% Diet 1/3 of cancers

Cigarette 1/3 of all cancers Occupational 5-20%

IV. PHYSICAL MUTAGENS - UV and ionizing radiation = 10% of all DNA damage.

A. UV

B. Ionizing Radiation

effect of physical mutagen (UV radiation)

wavelength?

effect on dna?

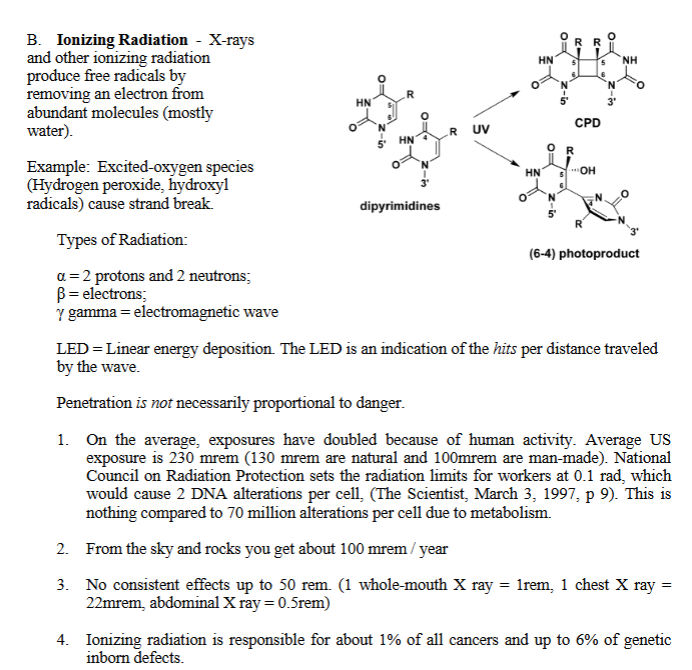

A. UV of 260nm (200-400nm) crosslinks thymine dimers. It also produces the 6-4 photo product.

When DNA is exposed to UV light, two adjacent thymine bases (T–T) on the same strand can react with each other.

They form abnormal covalent bonds.

This structure is called a:

Thymine dimer

= two thymines stuck together by extra covalent bonds.

This is NOT normal.

Normally, thymine should hydrogen-bond with adenine (A), not with itself.

physical mutagen (ionizing radiation)

X-rays

hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radicals

what do physical mutagens produce?

B. “Ionizing” Radiation - X-rays and other ionizing radiation produce free radicals (ions) by removing an electron from abundant molecules (mostly water).

Example: Excited-oxygen species

(Hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radicals) cause strand break.

These forms of radiation carry enough energy to damage DNA.

How they cause strand breaks1. Direct action: breaking the sugar–phosphate backbone

Ionizing radiation (X-rays, gamma rays) can hit the DNA and:

knock electrons off atoms

break covalent bonds in the backbone

This produces:

single-strand breaks (SSBs)

double-strand breaks (DSBs) if both strands are cut close together

DSBs are the most dangerous form of DNA damage.

Types of Radiation:

α = 2 protons and 2 neutrons;

β = electrons;

γ gamma = electromagnetic wave

LED = Linear energy deposition. The LED is an indication of the hits per distance traveled by the wave.

ionizing radiation (penetration)

“Penetration is not necessarily proportional to danger.”

Just because a type of radiation can penetrate deeply into the body does not automatically mean it is the most harmful.

Radiation exposure today is doubled due to human activities, but still small.

Natural sources give ~100 mrem/year.

Normal X-rays are far below harmful levels.

Metabolic processes cause vastly more DNA damage than typical radiation.

Ionizing radiation contributes little to overall cancer and birth defect rates.

V. BIOLOGICAL ENTITIES THAT CAUSE MUTATIONS

IS (insertion sequences)

retrotransposons (LINEs and SINEs)

retroviruses

translocations

transposons

transposable elements (and how to reduce transposable lements)

V. BIOLOGICAL ENTITIES THAT CAUSE MUTATIONS

IS (insertion sequences), retroposons (LINEs and SINEs), retroviruses, translocations, transposons, etc.

1. LINEs — Long Interspersed Nuclear Elements

2. SINEs — Short Interspersed Nuclear Elements

For example abl oncogene created by translocation in myelogenous leukemia. Remember that cancer is a multi mutation event, it needs at least 2 mutations in the same cell.

Trinucleotide repeats in DNA sequence makes the polymerase form loops, and their numbers expand. For example Huntington’s disease is seen when a triplet is amplified beyond a certain number of times.

Transposable Elements (TE) account for about 1/3 of the human genome, but are responsible only for about 0.2% of the mutations. Methylation and burying in heterochromatin (highly methylated areas of the chromatin) are ways to reduce the jumping activity of these elements.

A transposable element is:

A DNA sequence that can move from one location in the genome to another.

They are also called “jumping genes.”

VI. AMES TEST

salmonella

mutations

histidine

“The test developed by Bruce Ames to evaluate mutagenicity”

The ames test is a microbiological test for mutagens. It is based on the restoration of an inactivated gene in a Salmonella mutant strain.

This strain is cannot make the amino acid histidine, but mutations can restore the capacity to make histidine.

To improve the test, lipopolysacharides are removed from the cell wall (to reduce diffusion barriers) and an active liver homogenate is included in the medium (to produce potentially mutagenic derivatives of the test substance).

A filter paper disk is impregnated with the test compound, and is laid in the center of a Petri plate.

The plate contains a lawn of the mutant bacterium, but it can only grow if there is a mutation that reactivates its death gene for histidine

One important conclusion derived from the Ames test is that the relationship of dose to mutations is linear, with no threshold concentration, which can be deemed safe

Every additional bit of a mutagen causes additional mutations—there is no safe minimum amount.

More formally:

Linear relationship

= The number of mutations increases proportionally with the dose of the chemical tested.

Double the dose → double the mutations.No threshold

= There is no dose so small that it produces zero mutations.

Even extremely tiny exposures produce some measurable mutagenic effect.No safe concentration

= According to this theory, any exposure—even at very low levels—has the potential to cause mutations.

This underlies the “zero tolerance” philosophy used in early carcinogen regulation (e.g., the Delaney Clause you studied earlier).