AP Art History: Unit 3 – Africa/Indigenous Americas

1/27

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

28 Terms

Great Serpent Mound

Mississippian

1070 CE

Earthwork/effigy mound

sacred space, likely associated with supernatural power

intentional decision with material and location (adjacent to a creek, which it follows)

Mississippians had a highly organized gov’t

No burials or artifact in the mound

The shape of the snake was significant: its shedding has been associated with supernaturalism

They also believed that the snake in the mound had always been there, and that the mound helped to emerge it

Ruler’s Feather Headdress

Mexica (Aztec)

1428-1520 CE

Gold and feathers (quetzal and cotinga)

Came from male quetzals, which indicates long distance trade

Costume was incredibly important to the Aztecs; this piece was meant to be seen in the movement of the ruler

Luxury products were demanded from cities the Aztecs conquered

Spanish conquistadores were so impressed by this that they allowed these to continue to be produced after the conquest.

Great Zimbabwe

Shona peoples

1000-1400CE

Coursed granite blocks

Elevated surfaces for sleeping/sitting

“Dramatic architecture”

Held about 250 royal houses

Symbol of political and economic power (trade network)

Split into 3 parts: Hill Ruins and Great Enclosure possibly for elite or ritual purposes, while Valley Ruins were where people lived

Bundu Mask

19th–20th century CE

Sande Society, Mende peoples (Sierra Leone and Liberia)

Wood, cloth, fiber

Used in girls’ initiation rites

Only African mask worn by women

Idealized female beauty and moral virtue (high forehead for intelligence, pursed lips for wise speech)

Represents female water spirit and patron deity Sowo → the masks and dancers are said to become her at some points in the ceremony

Templo Mayor

1375–1520 CE

Mexica (Aztec)

Stone, volcanic stone, stucco

Twin temples dedicated to Huitzilopochtli (war/sun) and Tlaloc (rain)

Center of Tenochtitlán, reflects Aztec cosmology (axis mundli

Site of sacrifices and rituals — reenacting of Huitzilpotchli’s victory

Rainy season, sun sets behind Tlaloc, and behind Huitzilpotchli during dry season

Maize Cobs

c. 1440–1533 CE

Inka

Sheet metal/repoussé, gold and silver alloys

Idealized naturalism — Inca visual expression, as opposed to geometrical and abstract shapes from Andean culture

Symbol of agricultural abundance and ritual offerings

Part of garden of life-size/miniature ritual objects in Qorikancha

Likely taken as spoils after defeat of Inka in 1530s

Great Mosque of Djenne

c. 1200 CE (rebuilt 1906–1907)

Mali

Mudbrick

Largest mudbrick structure in the world; elevated on a platform, mainly for water damage preventing

Community re-plasters annually (Crepissage); represents devotion to God and community

Center of Islamic learning and trade to indicate economic health

Nkisi n’kondi (Power Figure)

c. late 19th century CE

Kongo peoples (DRC)

Wood and metal

Spiritual figure activated through rituals

Nails represent oaths, healing, or justice -→ if you recant on your promise, the deity will come after you

Filled with believed to be apotropaic substances - if they are removed, the deity is as well

Yaxchilan

725 CE

Maya

Limestone (structure and reliefs)

Likely a burial site for Lady Xoc and her husband

Known for lintels depicting rituals and royal lineage

Structure 23 shows Lady Xoc performing bloodletting to justify her husband’s rule

Demonstrates Maya hieroglyphic writing and dynastic propaganda

All-T’oqapu tunic

1450–1540 CE

Inka

Camelid fiber and cotton

Worn by elite, possibly emperor or sacrificed to sun god Inti

Weaving held spiritual and political importance, so the tunic was woven in one piece, as cutting the loom was thought to destroy spirit existence

Cochineal red and indigo blue dye were indicative of high status (camellid fibers were easier to dye)

Wall Plaque, Oba’s palace

16th century CE

Edo peoples, Benin (Nigeria)

Cast brass

Depicts Oba (king) and court officials, the Oba being significantly larger (hierarchy of scale)

Lost-wax casting tradition, which used immense amounts of brass from Portuguese traders

Showed wealth and divine kingship of the Oba

Aka Elephant Mask

19th–20th century CE

Bamileke (Cameroon, western grassfields region)

Wood, woven raffia, cloth, beads

Worn by members of Kuosi society, the highest society under nobility/royalty → a means to intimidate the lower classes

Elephant symbolizes power and wealth, and is considered to be the alter ego of the king

Danced at royal court celebrations

Chauvín de Huántar

900–200 BCE

Chavín (Peru)

Stone (architecture), granite (Lanzón and reliefs), gold alloy (jewelry)

Religious and ceremonial center of Chavín culture

Iconography combines human and jaguar imagery, which represents power

Pilgrimage site that helped unify people culturally; offering came from faraway places

Long maze like corridors that controlled access to sacred places and put visitors in a trance-like state

Bandolier Bag

c. 1850 CE

Lenape (Eastern Woodlands)

Beadwork on leather

Inspired by European ammunition bags, though these weren’t nearly as durable

Made by women, ceremonial regalia worn by men

Beadwork reflects cultural resilience and exchange

Pre-colonialism, decorative work was done by porcupine quills

Post-contact, glass beads from Venice were used

Embroidery was learned by Canadian nuns

Ndop (Portrait Figure)

760–1780 CE

Kuba peoples (Democratic Republic of Congo)

Wood

Idealized portrait of king (not literal likeness)

Acts as spiritual double of ruler

All placed together, so one could derive the royal lineage

All have the same seated pose, ornamentation, stoic expressions, and headdresses and blades

Mblo portrait mask

Early 20th century CE

Baule peoples (Côte d’Ivoire)

Wood, pigment, metal

Worn in dance performances (always by a man) honoring individuals (women)

Idealized features, reflects values of beauty and virtue

Performance includes music, dance, costume; the women’s mannerisms are studied and imitated during the performance

Said to be the spiritual double of a woman, so it can’t be commissioned without her permission

It can’t be seen without her or one of her close relatives being with it.

Transformation Mask

Late 19th century

Kwakwaka’wakw (Northwest Coast of Canada)

Wood, paint, string

Meant to be seen in movement; opens during performance to reveal second face (conceals and reveals identity)

Used in potlatch ceremonies

Represents spiritual transformation and clan identity (the belief that birds/fish/humans/animals differ only in skin + can transform into one another)

The Seattle Seahawks logo is a transformation mask

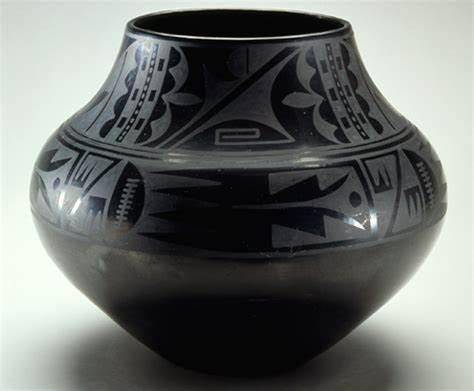

Black-on-Black vessel

c. mid-20th century

Puebloan, San Ildefonso, New Mexico; Maria Martínez and Julian Martínez

Blackware ceramic

Revitalized ancient Pueblo pottery techniques

Matte and glossy finish creates subtle decoration

Elevated Indigenous craft to fine art status

Sika dwa Kofi (Golden Stool of Ashanti)

c. 1700 CE

Ashanti peoples (South Central Ghana)

Gold over wood and cast-gold attachments

Symbol of Ashanti nation and soul of the people

Never sat upon, only by the stool itself

Represents unity and authority

Ikenga (shrine figure)

c. 19th–20th century CE

Igbo peoples (Nigeria)

Wood

Personal shrine representing a man’s power and success

Horns symbolize strength and determination

Ritual offerings and prayers made to it

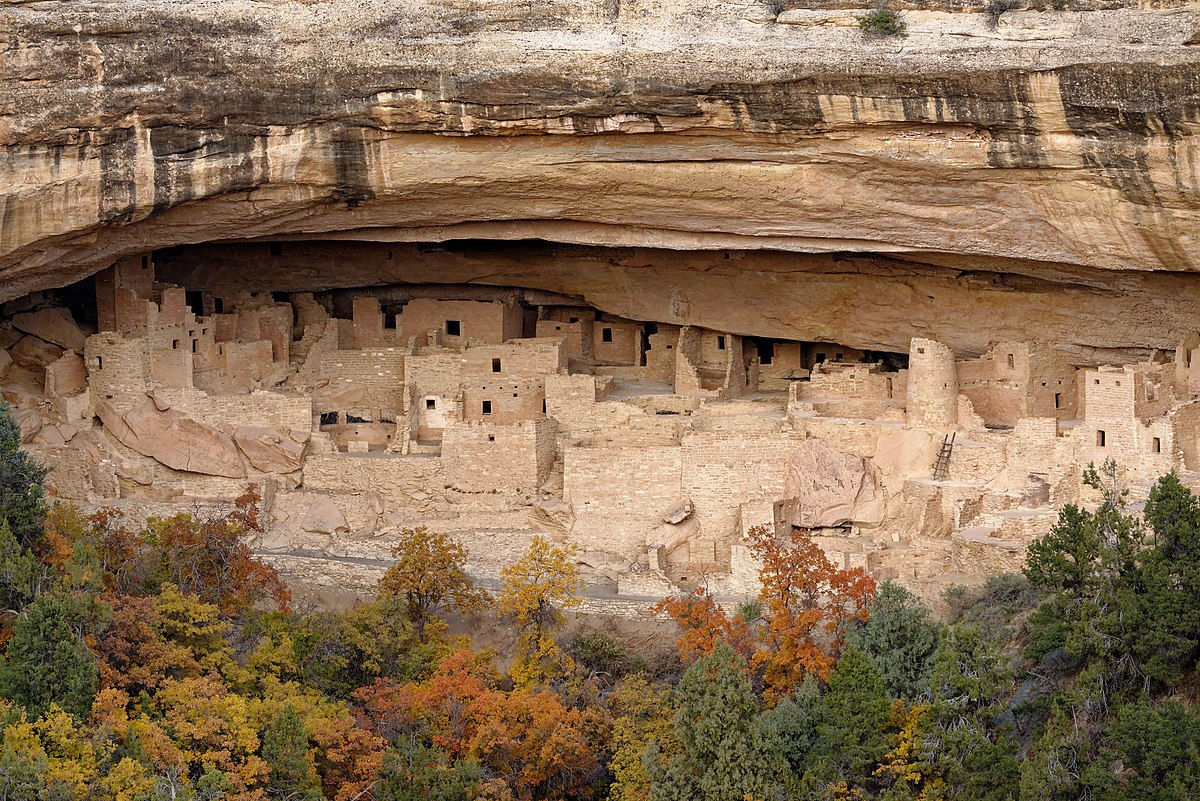

Mesa Verde Cliff Dwellings

c. 450–1300 CE

Ancestral Puebloan (Anasazi)

Sandstone, mortar, plaster

Built into cliffs for protection and insulation, and dwellings were very much elevated

Contained kivas (ceremonial spaces)

Shows community planning and adaptation to environment

Abandoned due to drought/migration

Painted Elk hide

c. 1890–1900 CE

Eastern Shoshone (Wind River Reservation, Wyoming); attributed to Cotsiogo (Cadzi Cody)

Painted elk hide

Depicts Sun Dance and buffalo hunt

Storytelling about the past (cultural preservation and pandering to collectors)

Paints were commercialized, so more vibrant colors were used than traditionally

Veranda post

c. 1910–1938 CE

Yoruba peoples (Nigeria) → Olowe of Ise

Wood and pigment

Functions as an architectural support post for palace

Senior wife’s placement indicates close, supporting relationship between her and king

Her eyes are alert and protective to ward off evil

Trickster god Esu announces the presence of the kind

Byeri (reliquary figure)

c. 19th–20th century CE

Culture: Fang peoples (Cameroon)

Medium: Wood

Guarded ancestral relics in cylindrical containers

Combines naturalism and abstraction

Ensured ancestral protection and continuity

During youth initiation rituals, they would be removed from the containers and set at the youth’s feet.

City of Cusco

1440 CE (Inca capital established earlier)

Inka

Andesite (stone)

Laid out in shape of a puma (symbolic of power in Inka culture)

Sits at 11,200 ft (extraordinary elevation)

Qorikancha temple was spiritual and physical center (axis mundli)

Lukasa

. 19th–20th century CE

Luba peoples (DRC)

Wood, beads, metal

Used by trained members to recount history and genealogy

Tactile reading of beads and shells

Encoded political and cultural knowledge

Pwo Mask

Late 19th–early 20th century CE

Chokwe peoples (DRC)

Wood, fiber, pigment, metal

Honors female ancestors

Worn by male dancers in initiation rituals

Symbolizes fertility and womanhood with Pwo being young, beautiful, and ready for marriage

Paired with Cihongo, the founding father → when danced together, they bring fertility and prosperity for all time

Identity is covered so “Pwo” can inhabit the body and teach the boys founding stories and to treasure women

City of Machu Picchu

c. 1450–1540 CE

Inka

Granite (architectural complex)

Royal estate of first Inka emperor

Lower elevation, but meant to be a place of entertainment, religious ceremony, and administering the affairs of the kingdom

Stones for the complex were laboriously shaped with tools, and fit together meticulously

Lower status buildings did not have the meticulously shaped stones of high Inka society + had rougher construction