4. Kingdom of Alba, Roman and Viking

1/21

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

22 Terms

Ptolomy’s 1st map of Europe, The islands of Albion and Hibernia’ (150AD) Orkney at top right, Caledonian Forest, Ireland on left, England at foot.

In the Roman imperial period, the area of Caledonia was north of the River Forth, while the area now called England was known as Britannia, the name also given to the Roman province roughly consisting of modern England and Wales and which replaced the earlier Ancient Greek designation as Albion.

The name for Scotland in most of the Celtic languages is related to Albion: Alba = Scottish Gaelic

Claudius Ptolemy (c. 100 – c. 170 AD) was an Alexandrian mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer.

In the service of the Romans he travelled around Europe and mapped everything including Scotland

The romans had been travelling around Scotland with Roman legions first arriving around AD 71, having conquered the Celtic Britons of southern Britannia over the preceding three decades.

Hadrians Wall begun 122 AD

A former defensive fortification of the Roman province of Britannia

Running from Wallsend on the River Tyne in the east to Bowness-on-Solway in the west of what is now northern England.

It was a stone wall with large ditches in front of it and behind it that crossed the whole width of the island.

Soldiers were garrisoned along the line of the wall in large forts, smaller milecastles, and intervening turrets.

In addition to the wall's defensive military role, its gates may have been customs posts

Context:

Romans invaded England founded civic centres across England in order to make a campaign north…

They built roads to service towns

In the campaign of Tacitus (first Roman emperor to reach Scotland)…the Romans were defeated by the Pictish tribes

Roman forts are found all over Scotland as well as marching towns

Hadrian returned and built Hadrians Wall - massive fortification that stretches along the border east-west roughly following the modern border

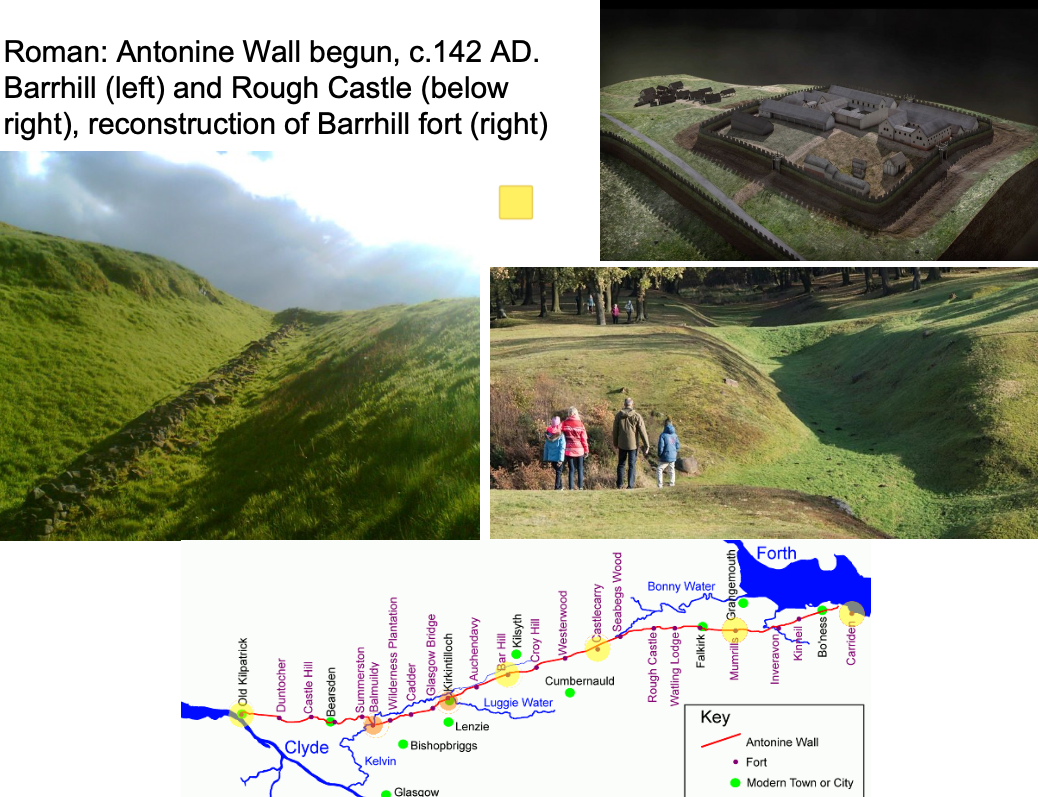

Roman: Antonine Wall begun, c.142 AD. Barrhill (left) and Rough Castle (below right), reconstruction of Barrhill fort (right).

A turf fortification on stone foundations, built by the Romans across what is now the Central Belt of Scotland, between the Firth of Clyde and the Firth of Forth

Construction began in 142 AD at the order of Roman Emperor Antoninus Pius.

Not strictly a wall but a rampart made of turf and ditches

Built approx. 20 years after Hadrian's Wall and intended to supersede it.

While it was garrisoned it was the northernmost frontier barrier of the Roman Empire.

It spanned approximately 63 kilometres and was about 3 metres high and 5 metres wide

At this stage situation in Rome was bad, they were under pressure from Vandals and Gauls so withdrew from Scotland without ever defeating it

Inside the fort (top right) it’s divided into four sections, consists of timber buildings and a central outlook tower to watch for attackers

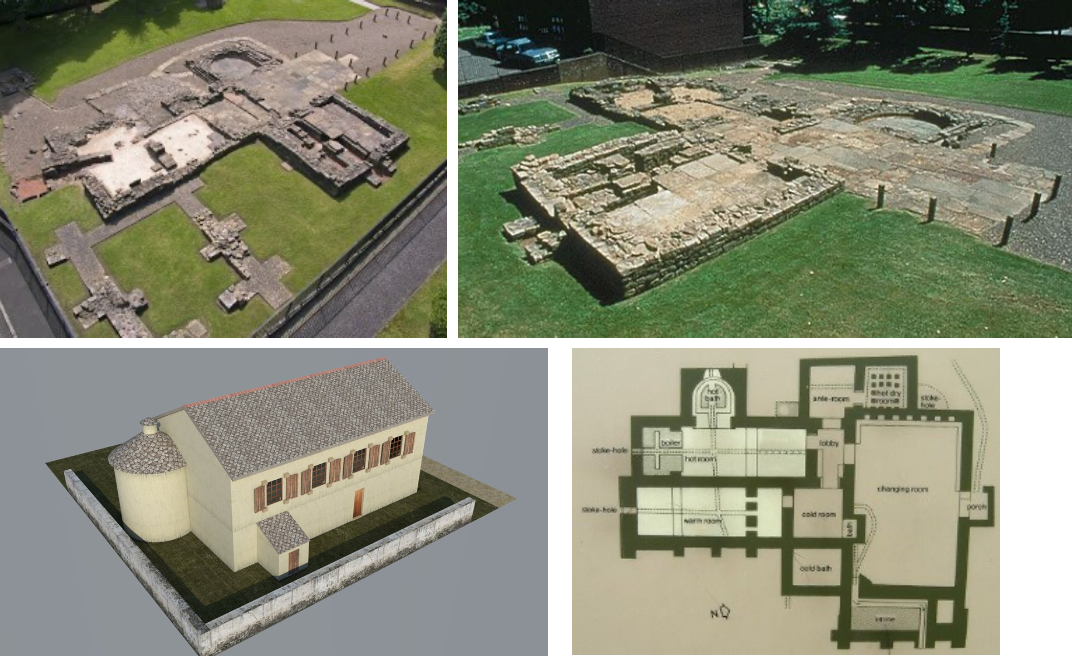

Roman: Bearsden bath-house, 2nd century AD to serve a small fort / Reconstrcution of Binchester Bath House, England

Romans also intersted in domestic comforts and enjoyed particularly Bath Houses

The fort which once stood at Bearsden is now mostly covered by roads and houses, but the bath house within its annexe can still be seen.

The well-preserved bath house and latrine give visitors an insight into the daily lives of the soldiers stationed along the Antonine Wall.

Bearsden was one of 16 known forts along the Antonine Wall, which was built across Scotland’s central belt from AD 140. The wall formed the north-western frontier of the Roman Empire.

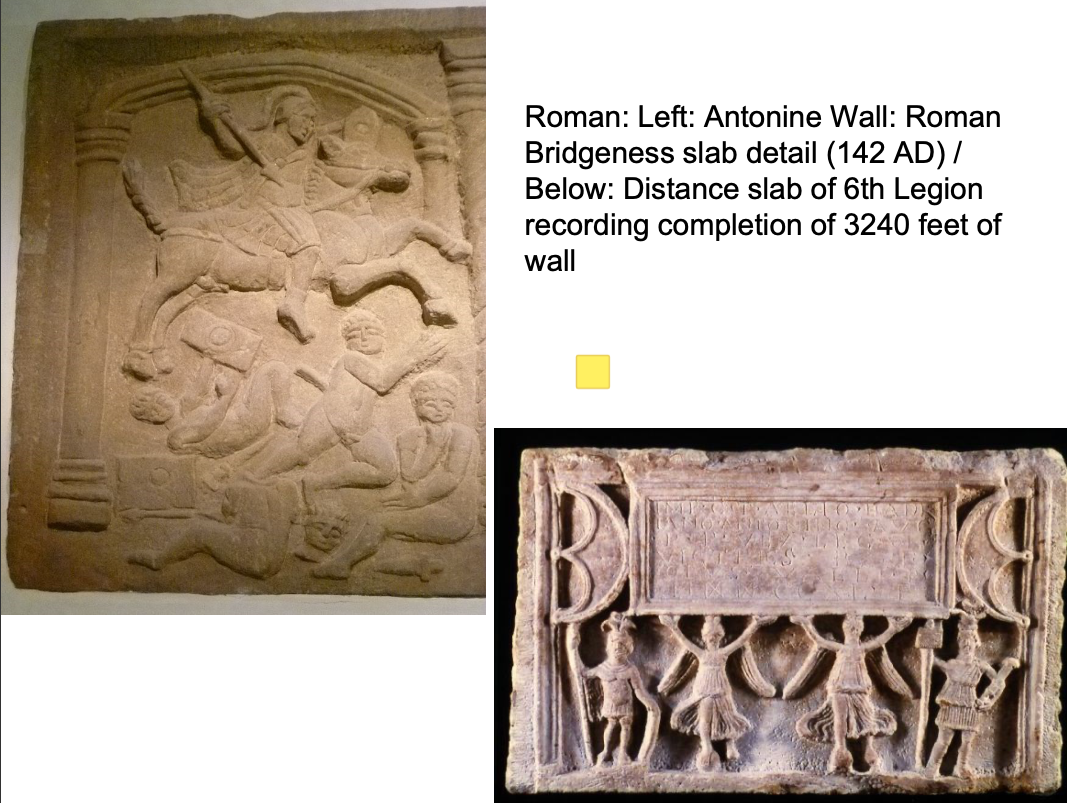

Roman: Left: Antonine Wall: Roman Bridgeness slab detail (142 AD) / Below: Distance slab of 6th Legion recording completion of 3240 feet of wall

Legions would have had an elite Roman officer and the under-soldiers would have been trained slaves from across the Empire

Roman Bridgeness slab

c. 142 AD

The Roman stone from Bridgeness (in modern Bo’ness, on the Firth of Forth) is one of the finest pieces of Roman sculpture from Britain.

It commemorated the construction of the eastern end of the Antonine Wall, the frontier built by the Romans across the narrowest part of Scotland between the Forth and Clyde estuaries, when they conquered southern Scotland in the 140s AD.

A whole series of such slabs were erected along the Wall…they detail various scenes related to conquest and religious ceremony

The panel glorifies the warfare and bloodshed involved in the conquest.

A Roman officer on horseback is riding down four local warriors.

The Roman is armed with helmet, body armour, shield, sword and spear.

In contrast, the locals are shown as naked, defended only by rectangular shields; their weapons (a spear and swords) have been cast aside.

This is very much a piece of propaganda intended to emphasise the difference between the ‘civilised’ Romans and their ‘savage’ opponents.

The scene compresses different events: the slaughter on the battlefield and the aftermath of the battle, with one captive beheaded and another contemplating his fate.

This triumphal image is a brutal and bloody reflection of frontier warfare, seen through the eyes of the victorious Romans.

Distance Slab of 6th Legion

These inscribed stones, known as distance slabs, celebrate the work of the legions which constructed the Antonine Wall in AD 142-43.

Evidence suggests that the slabs, all made of local sandstone, were set into stone frames along the length of the Wall and are likely to have faced South into the Empire.

Romans: Altar, Birrens (a Roman Fort), Dumfriesshire, dedicated to Discipline of the Emperor, set up by 2nd Cohort of Tungrians / Below, Cramond Lioness

Altar Birrens

2nd Century AD

Stone

Found at the site of the Roman fort at Birrens in Dumfriesshire

Dedicated to all the gods and goddesses.

Altars erected across the country to state that areas were dedicated to the service of Rome

Romans liked to use stone monuments as markers of areas

Cramond lioness:

Mid 2nd - early 3rd century AD

White sandstone

In 1997, a ferryman unearthed it at Cramond

One of the most important Roman finds in decades

Perhaps a memorial for a high ranking Roman officer.

Sculpture symbolises death, depicting a lioness devouring a naked bearded man. He has his hands tied behind his back, and represents a captive, probably a local Caledonian. The two snakes on the base symbolise survival of the soul.

In Roman times, death was not simply a matter of disposing of the body – it was a very important social occasion at which the living affirmed their relationships with the deceased and each other. Funerary rites marked aspects of the dead person's identity. The lioness would mark and protect the dead man’s grave and his memory.

Belongs to late Pictish period

Kingdom of Alba (late Pictish period): Class III stones (freestanding crosses); Dupplin Cross, (late 8th C. AD), Forteviot, Perthshire, inscription refers to Custantin, son of Urguist, Forteviot a royal centre until C12 / Upper right Camus Stone in from of Christian Cross, C10 AD, Angus

Belongs to late Pictish period

These are Class III stones

Dupplin Cross, (Late 8th Century), Forteviot, Perthshire

Thought to mark the site of a battle, the inscription refers to Custantin - one of the kings of Pict land

At the time when he was king, Christianity was no longer persecuted (indeed his name reflects the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity Constantine)

Latin cross with fineal ball in the centre, interlaced patterns along edges, various panels representing images

Thick sides with other ornamentation and panels detailing hunting scenes

Features figures of soldiers carved in relief

Also a panel perhaps representing Pictish court culture - harpist image functions perhaps as a bard that recites the genealogies of the King/Kinship

When Scottish Kings were crowned his ancestry was recited by the bard - the recitation of the hereditary line was a legal act authorising his kingship

Therefore important cultural functions are detailed

Camus Cross: (C10 AD)

The Camus Cross is an Early Medieval Scottish standing stone on the Panmure Estate near Carnoustie in Angus, Scotland.

First recorded in the 15th century, it is rare in Eastern Scotland.

Tradition and folk etymology suggest that the cross marked the burial site of Camus, leader of the Norse army purportedly defeated by King Malcolm II at the apocryphal Battle of Barry. The name of the stone is likely to derive from the extinct village of Camuston, which has a Celtic toponymy.

Pictish Stone Context:

A Pictish stone is a type of monumental stele, generally carved or incised with symbols or designs. A few have ogham inscriptions. Located in Scotland, mostly north of the Clyde-Forth line and on the Eastern side of the country, these stones are the most visible remaining evidence of the Picts and are thought to date from the 6th to 9th century, a period during which the Picts became Christianized. The earlier stones have no parallels from the rest of the British Isles, but the later forms are variations within a wider Insular tradition of monumental stones such as high crosses. About 350 objects classified as Pictish stones have survived, the earlier examples of which holding by far the greatest number of surviving examples of the mysterious symbols, which have long intrigued scholars

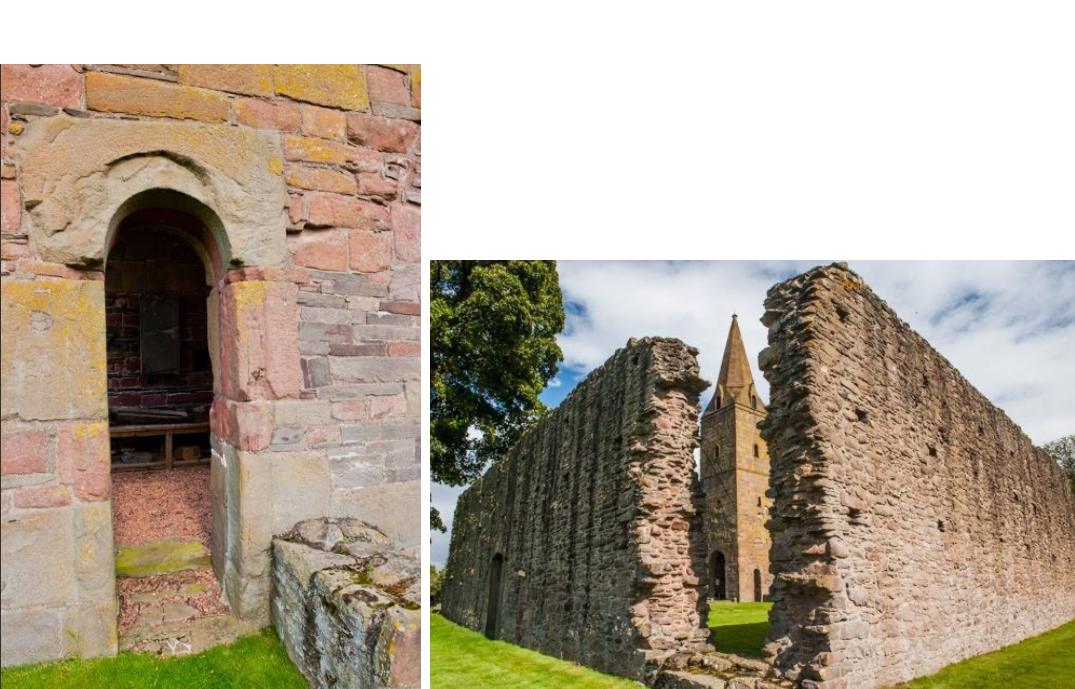

Kingdom of Alba: late Pictish period : Arch stone from chapel, possibly from the palace at Forteviot (Fortriu) early C9

The Forteviot Arch, Forteviot, Perthshire, Scotland, Northern Europe, late 9th or 10th century

Arch Stone was found in a river near a palace at Forteviot

Arch itself suggests a large palatial building

Part of a stone arch showing a cross, 'Agnus Dei' and figures of men

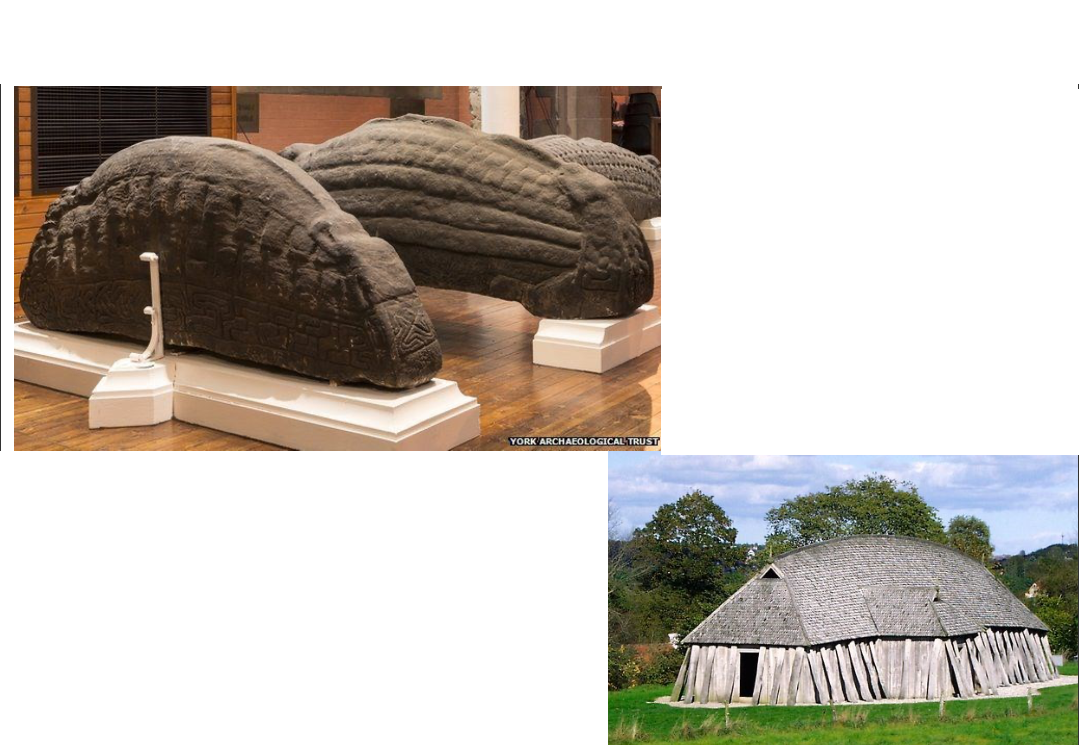

Viking: left: Belmont longhouse, Shetland / Right: Reconstrcution of Scandanavian wooden longhouse, interior (right), 9th–10th centuries AD

Belmont longhouse:

Boat-shaped with one curving wall and one straight wall (typical of Scottish longhouses).

High ceiling inside

Had large treeposts from tree trunks with wooden dowells at the top which wedge into the beams at the top

Wooden planking used for the roof

This leaves a nave-like gallery / banqueting hall for the chief Viking and his warriors to feast

Built on rock with Bronze Age cup marks.

Evidence of benches, hearths, postholes, gullies and paved areas.

There was also an outhouse or workshop outside.

Context:

Viking invasion of Scotland was very serious, permanent and damaging

Curved outer walls and straight ends reveals that this building accords to Viking architectural constructions

Viking: Shetland Amenity Trust's Architectural Heritage Team, reconstruction of Viking house, Brookpoint, Shetland

Built based on the excavated remains of the longhouse at Hamar, and elements from other excavations (all 9th-10th C. AD)

The craftsmen re-learnt traditional Viking building techniques, cutting each joint so the framework of the building is held together by the joints themselves, rather than nails.

The roof constructed from a wooden covering, with birch bark applied to keep the interior dry. This is then sealed with turf.

Vikings Context:

The Vikings were raiding in order to find land

In Scandanavia they became wealthy from trading with the East through the baltic (reaching the north of Russia and following the Neva across to Constantinople, sometimes even carrying their ships to find connecting rivers…they set up their own guard at Constantinople, they founded Russia and then set up trading routes to give them wealth)

Wealth meant they could feed their children and survive however they needed women, slaves, trading and most importantly, fertile land to grow food — since Scandanavia was mountainous and contained many fjords, not enough areas to effectively grow food

Women were also a factor as the Vikings were male-dominated…the women of Iceland for example contain Irish and Scottish heritage

Reconstructed Viking House, Denmark / Govan Parish Church, Hogback stones, 10th-12th century, Glasgow

Hogback Stones:

Dug up in the vicinity of the Church

Carved Anglo-Scandinavian sculptures, C10-12 Scotland, Yorkshire and Cumbria.

Likely grave markers.

Recumbent monuments, with a curved ridge and curved sides.

Decorated with 'shingles' suggest stylised 'houses' for dead, i.e., Scandinavian perhaps Danish type house.

Most hogback sites in Scotland found in maritime routes.

Forth-Clyde route connected York, England to Dublin.

There are two main types in Scotland warrior's tomb or house.

Govan Parish Church has 4 of largest known hogbacks, 5 in total, earliest is mid-C10.

The hogback combines Celtic and Scandinavian motifs

Celtic Church: cells, Left: Eileach an Naoimh (‘rocky place of the saint’) or Holy Isle, Inner Hebrides, c.542, Right: example of a Beehive-hut, Dingle Peninsula, Ireland / Gallarus Oratory, Ireland

Eileach an Naoimh (‘rocky place of the saint’) or Holy Isle.

The site of a monastery established by St Brendan of Clontarf in about AD 542

Isolation favoured by culdees.

Columba’s mother may have been buried here.

Destroyed by Vikings c. 800.

The most obvious remnants of the early monastic occupation are:

the unusual beehive cell

the grave enclosure traditionally associated with Eithne, mother of St Columba

a series of larger enclosures or burial grounds

Oldest ecclesiastical buildings in Scotland, earliest written record is late 9th century but possibly older.

The double beehive cell, standing at more than 3m tall, is the most visually striking remnant of the early monastery.

Hermetic cells built for Christians as private domiciles in which they could be closer to god — peace, quiet and away from the contamination of the pagan world

It’s laid out in a figure-of-eight plan, built of local sandstone split into thin slabs.

Monastic life on Eileach an Naoimh would have been similar to that on Iona in the AD 500s, with a cluster of communal buildings enclosed by a ditch or stockade, with an adjoining burial ground.

The original monastery was probably abandoned in the AD 800s due to Viking raids along the west coast, leaving the island uninhabited.

The island remained a place of pilgrimage and burial after its abandonment

Restenneth Priory, Forfar, Angus believed to have been founded by Nechtan, king of the Picts about 715. Church / Tower base c. late C11.

Lies at the heart of the old Pictish kingdom.

The earliest masonry dates to the 1100s, though it may well stand on the site of an ancient Pictish church built by King Nechtan c. 710 AD

Alexander I had the annals of Iona transferred to this site in the 1100s, and Robert the Bruce buried his young son Prince John here in the 1300s.

Much of the church we see today dates from the 1200s.

Image detail (left): Width of the arch is determined by the thickness / ability of the stone used for construction

Image detail (right): Outer precinct wall is very much associated with Irish and Celtic convents

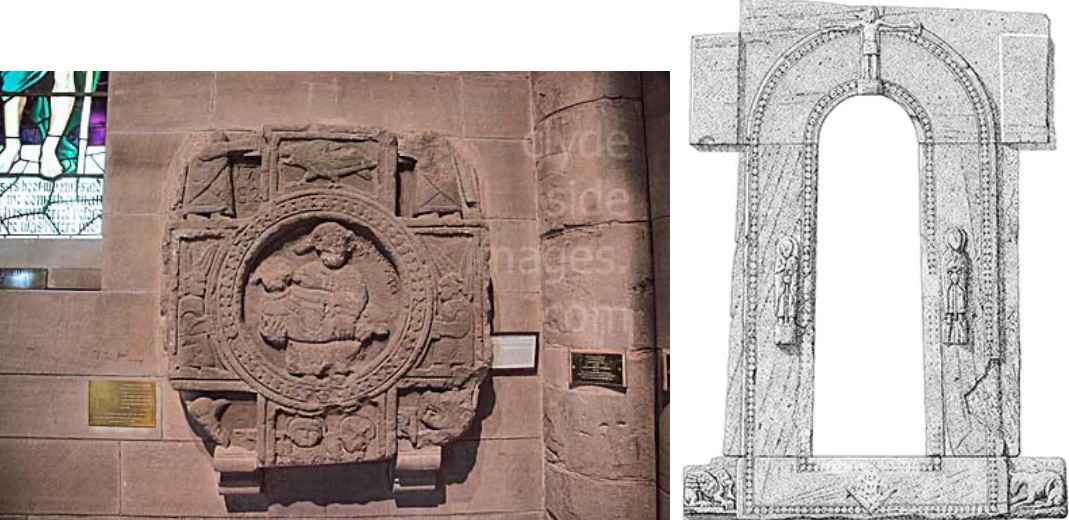

Celtic church: Left: Abernethy and Right: Brechin Round Towers, late C10-C11.

Context:

Round towers are typically Irish. Nearly 100 may have been built in Ireland between AD 900 and 1200, and more than 60 survive today.

primarily used as bell towers, though they also often found use as treasuries and refuges.

Only three round towers are known outside of Ireland: Abernethy (Perth & Kinross), Brechin (Angus) and Peel (Isle of Man)

Large monastic foundations — churches in the middle, precinct wall, graveyards, towers, monasteries

Steeply pitched roof with a steeple-like pencil tower emerging from its end

Pencil towers were built in the early 11th century

Abernethy (11th C. AD), Perth and Kinross

one of only two such towers surviving in Scotland—the other is at Brechin

22m tall and 5m wide.

A roofless sandstone tower

The twelve lower layers are of a different coloured stone to the rest of the building, leading to speculation that the base was built earlier than the rest.

There are indications that the tower originally had six wooden floors, probably connected by ladders.

There was a church at Abernethy from at least AD 600. It soon became the episcopal centre of the Pictish church, but was surpassed by St Andrews in the 1100s.

The Pictish symbol stone mounted on the tower was added in the 1900s

No one knows how Abernethy got its round tower, but over the years it has found use as a bell tower.

Brechin: (C11 AD), Angus

26m high, base circumference of 15m

Capped with a hexagonal spire of 5.5 m added in the 14th century.

The quality of the masonry is superior to all but a few of the Irish examples.

The narrow single doorway, raised some feet above ground level in a manner common in these buildings, is also exceptionally fine.

The door-surround is enriched with two bands of pellets, and the monolithic arch has a well-preserved representation of the Crucifixion.

The slightly splayed sides of the doorway (also monolithic) have relief sculptures of ecclesiastics

Relief sculpted figures — perhaps apostles

Plaques either side with Pictish styled animals

St Mary’s Stone, Brechin Cathedral, pellet band, Angus, 9th C AD

Beaded decoration along two channels of incised carvings

Pieta (Christ crucified with mother) relief carving in the centre

A carved Pictish cross-slab

Set against east wall of nave

One of the earliest Scottish sculptures with a Latin inscription.

Made of red sandstone

Measures 3ft x 3 ft

Kilmichael Glassary Bell-shrine C7-C9 reliquary in form of box containing iron handbell / St Fillan’s crozier C11 / Monymusk Reliquary of St. Columba, C8 Roayl Museum of Scotland

Kilmichael Glassary Bell-shrine, C7-C9, National Museum of Scotland

A relic of a saint, possibly Columba.

The bell inside dates to the 7th-9th century, the shrine to the first half of the 12th century.

The latter bears evidence in its design of a mixed artistic heritage, including local, Irish and Scandinavian influence.

St Fillan’s Crozier (C11 AD) and Coigreach (c. 13th C AD), NMS

The St Fillan’s Crozier and Coigreach are two separate yet connected objects.

Both are associated with Fillan, who according to tradition was an early-medieval abbot who settled in Glendochart in Perthshire.

Crozier is Bronze

Coigreach is made of Silver, gold, rock crystal

What is a Crozier?

A staff of office usually surmounted by a crook, representing the pastoral authority of a bishop, symbolising their role as the shepherd of their ‘flock’.

The St Fillan’s Crozier is made in the characteristic West Highland style, decorated with a mixture of materials.

What is a Coigreach?

A silver-gilt reliquary encasing the Crozier.

Monymusk Reliquary of St. Columba, C8, NMS

Reliquary contains part of St. Columba’s hand — taken from Iona

Made from wood, covered in bronze and silver plates

Decorated with animals and enameled bronze mounts

What is the Monymusk Reliquary?

Reliquaries housed precious relics associated with Christian saints, although the Monymusk Reliquary is now empty.

The casket and lid are carved from a solid piece of wood, and covered in thin bronze and silver plates.

The silver plates are decorated with faint interlacing animals

Celtic (Irish origin) church: Iona Abbey: St Columba’s Shrine, possible place of saint’s burial in 597 / Lower centre: St Martin’s Cross (early C9) / St John's Cross in Abbey museum / Replica of St John’s Cross in front of Abbey portal

Iona Abbey

Iona was one of the oldest Christian religious centres in Western Europe.

The abbey was a focal point for the spread of Christianity throughout Scotland and marks the foundation of a monastic community by St. Columba (who arrived in 563 AD), when Iona was part of the Kingdom of Dál Riata.

Around 800AD the original wooden chapel was replaced by a stone chapel

In the 12th century, the Macdonald lords of Clan Donald made Iona the ecclesiastical capital of the Royal Family of Macdonald, and subsequent Lords of the Isles into the early 16th century endowed and maintained the abbey, church and nunnery.

The Abbey (restored in the 20th century) is largely the legacy of the 15th century Clan MacDonald, Lords of the Isles

St Martin’s Cross & St. John’s Cross (8th C.)

Several high crosses are found on the island of Iona.

A replica of St John's Cross is found by the doorway of the Abbey.

The restored original is located in the Infirmary Museum at the rear of the abbey.

Kells, St John's Gospel, incipit (the opening of a manuscript), 9th Century

St. John features at the top

Intense detail in the composition/design — v enriched

Vellum (calfskin) used as material

3-4 monks would have worked on this

Lapis Lazuli from the east and gold from ireland

This lavish text opens the Gospel of John

Book of Kells Context:

The Book of Kells is one of a group of manuscripts in what is known as the Insular style, produced from the late 6th through the early 9th centuries in monasteries in Ireland, Scotland and England.

The proposed dating in the 9th century coincides with Viking raids on Lindisfarne and Iona, which began c. 793-794 and eventually dispersed the monks and their holy relics into Ireland and Scotland

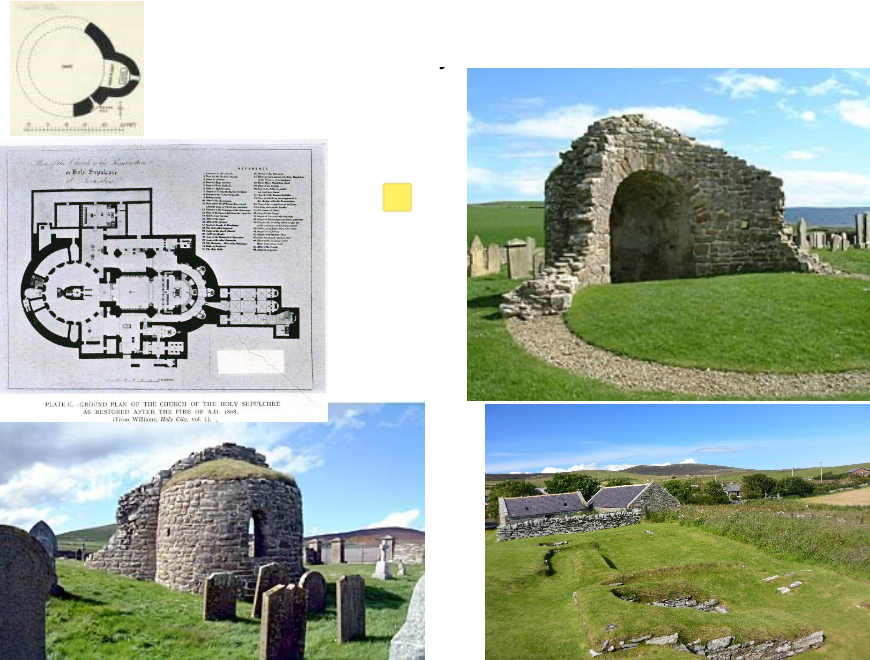

Orphir Round Kirk and Bu, Orkney, dated c. 1090 — 1160 by HES

Round Kirk and Bu

Bu = a drinking hall…specifically for Vikings

The ruined church, dedicated to Saint Nicholas, consisted of a barrel-vaulted apse on the eastern side of its 6 metre wide circular nave.

The walls are one metre thick

Contains an apse…

Apse = east facing curved section of the church, contains the altar, thus most sacred area of the church which is segregated from the congregation

Perhaps built by Jarl Haakon Paulsson of Orkney as penance for murdering his cousin in the late 11th century.

According to the Orkneyinga saga, he took sole power in 1117 after killing his cousin Magnus

The saga refers to a "large drinking-hall" with a "magnificent church" nearby. The remains of the drinking hall, known as the 'Earl's Bu', can still be seen (bottom right)

It is the oldest surviving round church in Scotland, a circular design is highly unusual for Scotland

Design was inspired by the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem — circular churches became a popular design re-told by returning crusaders

Semi-circular apse has a tall, slender window composed of different segments of stone / voussoirs

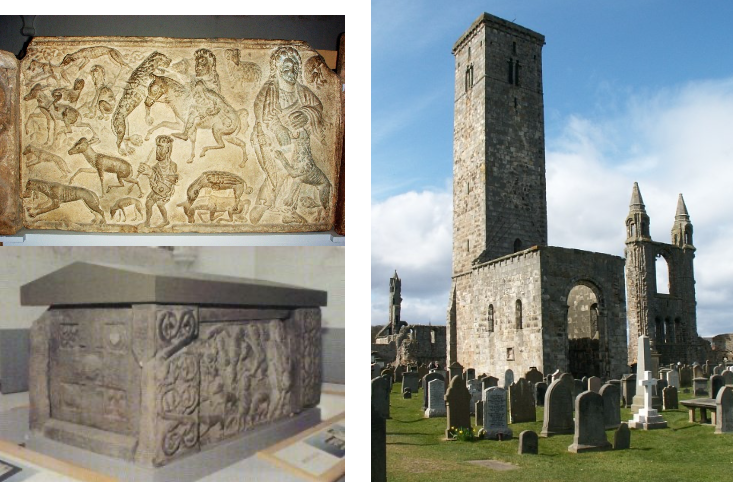

St. Rule’s Church, St. Andrews, c. 1130 / Relics of Apostle Andrews brought to Scotland by St. RulPossibly displayed on a feretrum. Below, St. Andrews sarcophagus, late C8 Pictish

St. Rule’s Church, St. Andrews (Fife)

The small building now known as St Rule's Church was once St Andrews' main cathedral.

Built c. 1130, as the first place of worship in Scotland for the newly arrived Augustinian canons.

This Continental reformed order supplanted the existing clergy.

It was perhaps built by workmen from northern England.

Romanesque (or Norman) style

30m tall St Rule’s Tower

A beacon for pilgrims heading for the shrine of St Andrew

Late 12th century St Rule's was superseded by the much larger cathedral whose ruins it stands beside.

St. Andrews sarcophagus, late C8 Pictish

Recovered in 1833 during excavations

It would have comprised two side panels, two end panels, four corner pieces and a roof slab.

The roof slab and other panels are missing

Constructed of local sandstone.

The surviving side panel shows, from right to left:

A figure breaking the jaws of a lion

A mounted hunter with his sword raised to strike a leaping lion

A hunter on foot, armed with a spear and assisted by a hunting dog, about to attack a wolf.

The surviving end panel = a cross with four small panels between the arms.

Historians differ on who was likely to have been interred in the sarcophagus.

Perhaps the Pictish King Óengus

Iona, Western Isles: St Oran's Chapel, before 1164 (left) / Nunnery 1203 (right) / Monumental Grave Slabs

St. Oran’s Chapel, C12

Norman chapel

Oran was a convert who is said to have been buried alive in order to consecrate the ground for the building.

During the 9th-11th centuries the cemetery became a royal burial ground.

In mid C16 an inventory of 48 Scottish, 8 Norwegian and 4 Irish kings was recorded.

None of these graves are now identifiable

The chapel is a plain oblong building with an elaborate doorway

Numerous monumental slabs are preserved in the chapel

2nd to the right is dedicated to Agnus Og in 1314-18

Middle one dedicated to Donald I (d. 1247)

Iona Nunnery, 1203 AD

An Augustinian convent of nuns located on Iona

Established shortly after the foundation of the nearby Benedictine monastery in 1203

Now in ruins but form the most complete remains of a medieval nunnery extant in Scotland.

After the Reformation, the priory was dissolved and reduced to a ruin.

The construction of Nunnery follows the typical Irish style.

Consists of a building with three bays with a passage to the north side and a small chapel on the east side of the passage.

The east wing had three rooms on ground level, above was the dormitory.

The south wing contained the refectory.

The west wing was for guests

Simple arches and clerestory above

Lecture Notes on Context:

Iona was one of the most important Christian centres during the dark ages (“when Europe falls into barbarity amidst the destruction of old civilised Roman centres across Europe”)

The collapse of the Roman Empire left a vacuum/loss of human knowledge

Shift in centre to Constantinople

Charlemagne took control

He had Irish priests at his court in Aachen…Ireland had been relatively untouched from barbarism other than the Vikings…Oddo was sent by Charlemagne to find out about early Christian architecture pre building the palatine chapel

Iona becomes one of the great centres of learning...

At this period the Vikings have settled along the west coast…there is a Viking king buried here (bottom left image)…King Sommerled was perhaps Christian…

Vikings were christianised by the state in 700 AD??

Kings and Queens of Ireland were brought over to be buried on Iona as were the early Kings of Scotland — it is thus an incredibly important religious site!

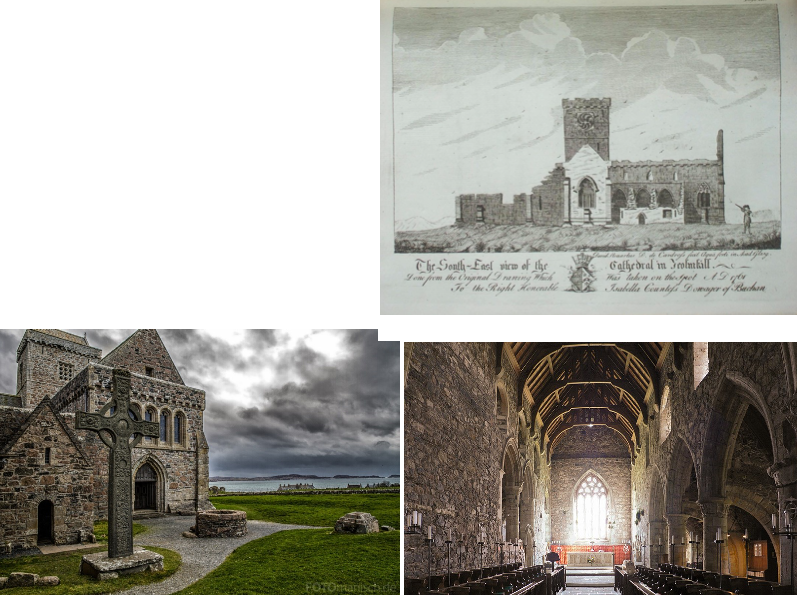

Iona: Michael Chapel, early 1200s, restored Abbey / Iona Abbey, 1761

Benedictine Abbey Church erected the 1200s

Built on the site of its predecessor, a stone church built in the years up to 825.

The Michael Chapel is a small chapel built in the early 1200s.

The Michael Chapel is built on a more exact east-west alignment than the later Abbey Church.

Like Iona Abbey, the chapel became derelict following the Reformation of 1560.

One of the last buildings to be restored by the Iona Community in 1959