Markets and Regulation Master

1/129

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

130 Terms

Core Principles of Economics

Efficiency: benefits > costs

Pareto efficiency

Kaldor-Hicks efficiency

Should the law aim to be efficient? —> Posner’s, Friedman, Cooter and Ulen

Welfare: Utility = satisfying desires

Transaction: transfer of property rights

Pareto efficiency

an allocation is efficient when one person is made better off without making someone else worse off (win-win)

Kaldor-Hicks efficiency

an allocation can be efficient even if someone loses, as long as the winner(s) could compensate the loser(s) (potential win-win)

Should the law aim to be efficient?

Posner’s ex-ante consent argument: before knowing our place in society, we would all choose efficient rules

Friedman’s argument: efficiency matters to most people; legal systems often designed to generate efficient outcomes

Cooter and Ulen: efficiency is crucial for the legal system, but society also addresses other goals

Market failure

imperfect competition

external effects

public goods

information asymmetries

Regulatory failure

incomplete information

lobbying

short time horizon

budget maximization

corruption

perfect competition

market = demand and supply

characteristics:

many suppliers and consumers

homogeneous goods

no transaction costs (perfectly transparant; property rights defined; free entry and exit)

MR = p

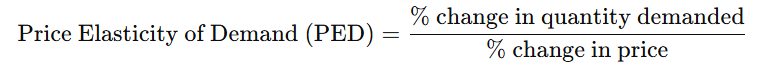

Price elasticity

Price elasticity of demand tells you how much the quantity demanded of a good changes when its price changes.

consumer surplus

difference between price that consumers are willing to pay and equilibrium price

producer surplus

difference between equilibrium price and price that entrepreneurs want to receive

monopoly

In a perfectly competitive market the price is given, the producer can only control the quantity provided and MR = P. Profit is maximised where MR=MC.

Producers aim to maximize profits: profits are (always) maximized where MR=MC.

The MR line is downward sloping in a monopolistic market, because the monopolist can set the market price. TR highest when MR = 0

welfare costs of monopoly

rent-seeking: welfare costs of maintaining monopoly

x-inefficiency: relatively weak incentive to control costs

dynamic inefficiency: relatively weak incentive to innovate

oligopoly

few suppliers (homogeneous oligopoly / heterogeneous)

no unequivocal oligopoly theory

behavior: preferably no price competition, firms coordinating behavior via cartel/merger

Cartel

oligopolists acting together as monopolist

economically unstable

free-riding: produce more than illegally agreed

collective action problem: cartel only enforceable in a small group of firms

entry: cartel’s excess profits attract new competitors

Monopolistic competition

many suppliers but heterogeneity of the product creates a monopolistic situation

not just price but also other product characteristics matter

every product has its own submarket where producer can behave like a monopolist

welfare increasing compared to monopoly

Deadweight loss

the loss of total economic efficiency that occurs when the equilibrium in a market is distorted, usually by things like taxes, subsidies, price controls, or monopolies.

Analyze imperfect competition

Imperfect competition refers to market structures where the assumptions of perfect competition—many buyers and sellers, identical products, and full information—do not hold. In these markets, firms have some control over prices, leading to higher prices, lower output, and reduced efficiency compared to perfect competition.

Types include:

Monopoly: one firm dominates, setting prices high.

Oligopoly: a few firms may collude or act strategically.

Monopolistic competition: many firms offer similar but differentiated products, leading to brand-based price differences.

The result is often deadweight loss, less consumer surplus, and potential for market abuse unless regulated.

types of public goods as market failure

non-exclusive: no individual can be excluded from its use

non-rivalrous: use by one individual does not reduce the availability to others

Tragedy of the commons

tendency for a resource that has no price to be used until its marginal benefit falls to zero

quasi-public goods

private goods partly financed by the government

negative externalities vs. positive externalities

Damage to others without compensation (noise)*

VS

Others profit without paying (dike).

external effects definition

(1) advantages or disadvantages associated with the consumption and/or production of a good

(2) that fall on or accrue to other people than the direct users of that good

(3) without financial compensation.

Coase theorem conditions

conditions:

no/low transaction costs;

no public good;

parties have sufficient means to compensate;

clear property rights

how to internalize externalities when transaction costs are positive

taxation

direct regulation

liability law

asymmetric information

seller has more/better information than potential buyers

reduces the average quality of goods offered for sale

potential solutions:

parties can communicate knowledge truthfully

regulation & self-regulation

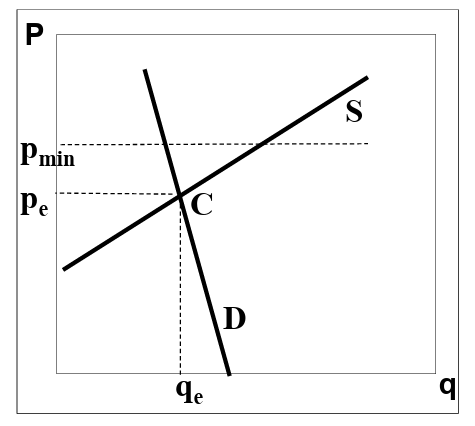

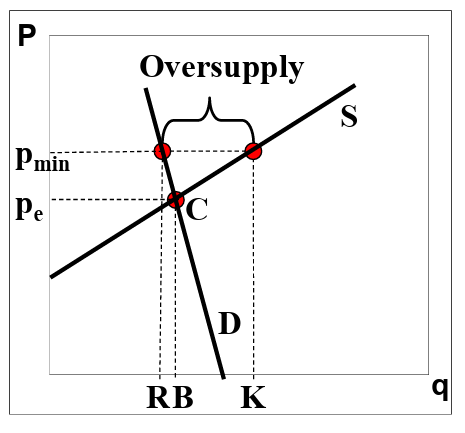

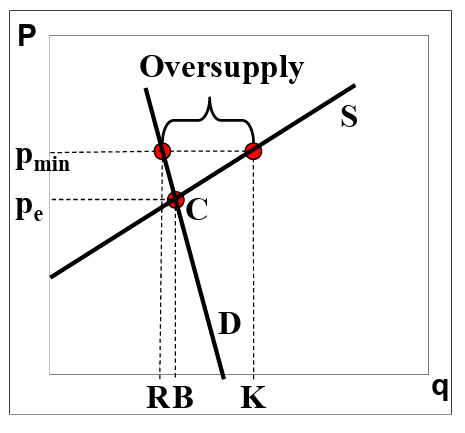

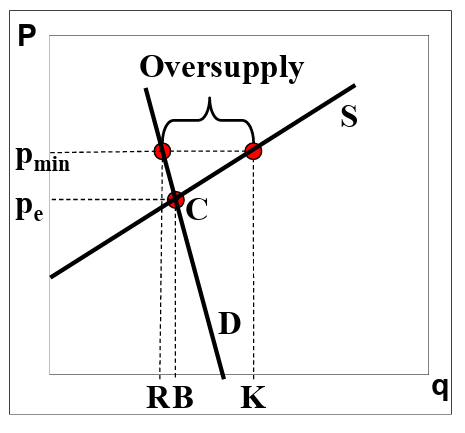

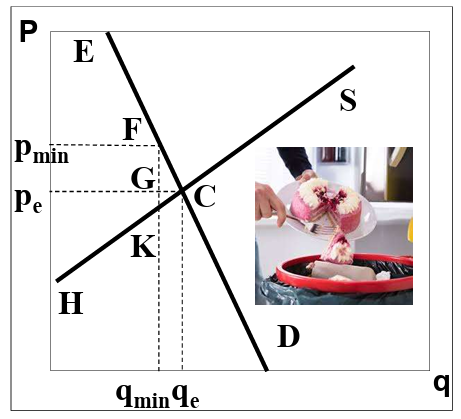

What is the effect of the minimum price Pmin on the quantity supplied and the quantity demanded?

Effect minimum (or: floor) price Pmin:

Supply = q(K); Demand = q(R)

Oversupply q(RK) = ‘milk lake’!

What is the effect of the minimum price on milk producers’ revenues?

Effect minimum price on producers’ revenues:

in equilibrium revenue = Pe x q(B)

Now higher revenue: Pmin x q(R)

Do milk consumers gain or loose from a minimum price?

Consumer pays twice:

higher price for milk (smaller consumer surplus)

extra tax money needed to buy up ‘milk lake’

Would a minimum price for milk be efficient or inefficient for society at large?

At Pmin demand is qmin

consumer surplus is EFPmin

Producer surplus is HKFPmin

Welfare loss is KCF

hence: (Pareto-) inefficient

minimum price for milk could be seen as fair (for producer) or as unfair (for consumer); but: consumer pays twice

minimum price for milk is inefficient due to welfare loss for society at large

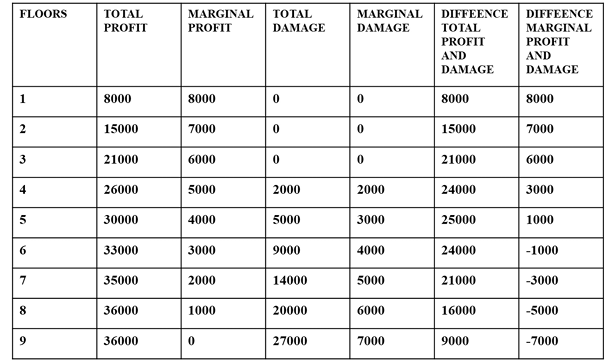

Nuisance case: project developer vs local residents

Project developer: higher apartment building = higher profit

Local residents: higher apartment building = more damage (in the form of loss of living enjoyment)

See the table: how many floors should the judge allow to ensure an efficient allocation of rights?

Efficient allocation is realized with 5 floors where MR=MC, namely where marginal profit is equal to or at least still higher than marginal damage (or: where the difference between total profit and total damage is the biggest)

Nuisance case: project developer vs local residents

Project developer: higher apartment building = higher profit

Local residents: higher apartment building = more damage (in the form of loss of living enjoyment)

Suppose the judge allows 3 floors: will he project developer comply or build more floors in case of a liability protection of local residents?

When the judge allows 3 floors, the project developer will still build 5 floors, because he can increase his profit by building 2 extra floors even though he has to compensate the damage for the local residents

Emissions trading is a market-based instrument to achieve an emission reduction target cost-effectively by allowing companies to buy and sell emission allowances. In the EU, companies are legally obliged to cover their yearly emissions with (an equal amount of) CO 2 16 emission allowances.

Prior to 2013, electricity producers received their tradable emission allowances for free, but they passed through the market value of those rights in the electricity price.

Consumers then accused producers of making windfall profits and argued in favour of more competition in the oligopolistic electricity market to stop or at least reduce those windfall profits.

Will more competition in the electricity market reduce or even make an end to those windfall profits from free allowances?

›💰 Opportunity costs of free emission allowances are passed on to consumers no matter what the market structure is.

⚡ More competition = bigger price increase = more cost passed to consumers

→ Called “windfall profits” by policymakers.✅ In competitive markets, price = cost (P = MC), so this is normal.

😃 More competition = lower electricity prices for consumers overall.

📈 Passing on opportunity costs is economically correct, even if it causes windfall profits.

🛑 Want to avoid windfall profits? → Auction the emission allowances instead of giving them for free (as done after 2013).

🌍 Higher electricity prices help society by putting a price on CO₂, which helps fight climate change.

Property rights

A bundle of rights that include:

right of use

right to enjoyment

right of exclusion

right of disposition

and right to split the bundle

exclusion and disposition make exchange possible

How do laws influence transaction costs

They may reduce or increase transaction costs depending on their design

default rules: govern situations not regulated by contract parties

binding power of agreements: reduces monitoring costs for parties

good faith: limits strategic behavior when interpreting contracts

Coase theorem

Allocation of property rights does not matter for efficiency (unless transaction costs)

Social costs = external costs

by negotiating over rights, externalities can be internalized so that social costs cannot exist in the micro-economic model

extra assumption necessary for social cost: the existence of transaction costs

For efficiency it doesn’t matter to whom the rights are allocated because without transaction costs parties can negotiate to internalize the externality

Validity of Coase Theorem is limited due to transaction costs - in case of transaction costs allocation does matter for efficiency

transaction costs

the time, money and paperwork it takes to make deals

Calabresi and Melamed

property rule A = A prohibits damage by B;

liability rule A = B may cause damage, provided A is compensated;

property rule B = B may cause damage (unless transfer of entitlement to A);

liability rule B = A prohibits damage by B, provided B is compensated.

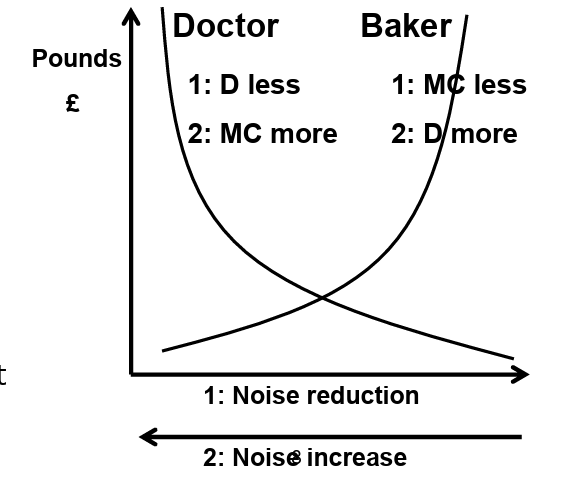

Sturges versus Bridgman: Nuisance case 1879: doctor Sturges moved next door to baker (confectioner) Bridgman

Doctor: ‘The noise disturbs me: it “causes great discomfort and annoyance”’

Baker: ‘I was here first: “during the last sixty years [we] carried on the business”’

› Court ruling: Doctor has right to work in silence (nuisance weighs more than doctor coming to the nuisance) › Coase: more efficient would have been to negotiate (or mediate) and allow for some noise

› Conclusion Coase: doctor right or baker right does not matter for efficiency

Both in option 1 and in option 2 parties choose the intersection of both curves where P = MC

Additional conclusion: Choice is not so much between noise or no noise, but between a lot of noise or little noise

Efficient breach of contract

End the agreement, breach the contract, if this provides an advantage to the breaker, provided he fully compensates the other party for damage

magnitude of compensation: such that the counterparty remains at least equal in welfare

breaker then internalizes full costs of breach of contract

only breach of contract if the benefit of non-compliance is greater than the welfare loss of the counterparty to be compensated: breach of contract is then Pareto efficient

Under efficient breach of contract, there is a choice between property rule or liability rule protection (Calabresi & Melamed)

Nuisance case: factory smoke vs local residents

✅ Total surplus is higher when smoke is emitted:

With smoke: €600

Without smoke: €580

📈 Niemeyer gains €40 more by emitting smoke:

From €160 → €200

📉 Lefier loses only €20 from allowing smoke:

From €420 → €400

⚖ Net gain to society:

Gain (€40) is greater than loss (€20)

💬 Lefier has the right to allow or block the smoke

🤝 Niemeyer can compensate Lefier (e.g., €30):

Lefier's loss (€20) is covered + €10 bonus

Niemeyer still gains €10 (after paying €30)

🔁 Result: Smoke is emitted, but the harm is internalized through negotiation → efficient and fair outcome

The bargain theory

principle: Promise is enforceable if part of a bargain, otherwise it is not

elements: offer, acceptance, and consideration (what promisee gives to induce the promise (reciprocal inducement)

the focus is on the presence of consideration, not adequacy

Economic critiques of the bargain theory

Underinclusiveness:

Fails to enforce promises that both parties want enforceable but lack consideration.

Frustrates potentially beneficial exchanges.

Bargain theory can be dogmatic (rigid rules) vs. responsive (serves parties' desires).

Examples: Firm Offers, Charitable Pledges.

Modern law uses doctrines like Promissory Estoppel to address this.

Overinclusiveness:

Mandates enforcement of any bargain, even if unfair, deceptive, or exploitative.

Ignores issues like fraud, duress, unequal bargaining power.

Example revisited: The Grasshopper Killer- Strict bargain theory enforces, but modern law voids for fraud.

Economic analysis explains why doctrines like Fraud and Unconscionability exist (correcting market failures).

The paradox of commitment

refers to a situation where being able to commit less (or being more flexible) actually leads to a worse outcome, while committing more strictly—even if it limits your options—can lead to a better result.

The paradox of limiting options

Purposes of contract law

facilitate efficient trade where trust and commitment are needed

to incentivize efficient level of performance and breach

to minimize transaction costs of negotiating contracts by supplying efficient default rules

Expectation damages

Puts promisee where they’d be if the contract was performed (“benefit of bargain”)

incentivizes efficient performance (perform only if cost < value)

Goal: put the victim in the position they would have been in had the contract been performed

Baseline: the state of the world with performance

Economic aim: make the victim indifferent between performance and breach + damages

Why? forces the breacher to internalize the victim’s full expected gain

Overreliance

when the promisee (the person relying on a contract) invests more in reliance on the contract being fulfilled than is economically reasonable, because they expect to be fully compensated if the contract is breached.

How do you mitigate overreliance

Hadley v. Baxendale:

problem: high damages (insuring reliance) can lead to promisee overreliance

economic solution: limit compensation for unforeseeable reliance. Promisee bears costs of unusual, undisclosesd reliance

legal doctrine: foreseeability rules

damages limited to losses foreseeable to the breaching party at contract formation

economic effect: caps damages, making promisee bear the cost of unforeseeable reliance. Incentivizes promisee to disclose unusual reliance to the promisor

Default rules

Real-world contracts are incomplete and have gaps due to the transaction costs of making a comprehensive contract - these help fill the gaps and provides efficient rules that parties would have agreed to in order to save transaction costs (majoritarian defaults)

Mandatory rules

sometimes courts override explicit contract terms

economic justification: correcting market failures or protecting third parties/public interest

examples:

lack of rationality: incompetence, duress, necessity

asymmetric information: fraud, duty to disclose, mutual mistake

monopoly power: unconcionability

externalities: public policy violations

Cooperation beyond formal enforcement

relational contracts: long-term relationships where trust, reputation, and informal norms are key

repeated interactions: enable informal enforcement

effective for ongoing relationships, smaller stakes per interaction

the endgame problem: informal methods weaken when relationship ends

formal contracts complements informal methods, crucial at start/end

Types of remedies

court-imposed: damages and specific performance

party-designed: liquidated damages

Incentives

Influence decisions before and during contract life:

contract formation

Investment in performance

reliance on promises

breach or performance

Reliance Damages

Restoring the pre-contract position

goal: put the victim in the position they would have been in had the contract never been made

baseline: the state of the world without any contract

key idea: compensate for losses incurred because the victim relied on the promise = > Protects against wasted investments

economic aim: make the victim indifferent between no contract and breach + damages

Opportunity cost damages

goal: put the victim in the position they would have been in had they signed the best alternative contract

baseline: the value of the foregone opportunity

idea: compensate for the lost opportunity of making a better deal elsewhere

Compare Damage Measures

Typical relationship:

expectation damages > opportunity cost damages > reliance damages

Why?

you choose the most valuable contract available

the contract is expected to be more valuable than no contract

expectation protects the full value of your chosen contract

opportunity-cost protects the value of your next-best option

reliance only protects against losses from changing position

Subjective value

Hawkins V. McGee (The Hairy Hand case)

facts: doctor promised a perfect hand, delivered a much worse hair hand

problem: how to measure damages when the value is subjective and has no market price?

Highlights: difficulty applying standard damages when subjective value differs from market value

Specific performance

Court orders the promised performance instead of damages

typically used when:

goods are unique

damages are hard to calculate

close substitutes don’t exist

economic considerations

avoids difficulty of valuing subjective loss

gives promisee strong bargaining power

may lead to inefficient performance if renegotiation fails

Liquidated damages

a fixed amount of money that two parties agree in advance will be paid if one of them breaks the contract.

It’s used to avoid arguing later about how much harm was caused — the amount is set upfront to make things clear and simple if something goes wrong.

💡 Think of it like a pre-agreed “penalty” for not keeping your promise.

Do different remedies lead to efficient breach?

coase theorem: costless bargaining = efficient outcomes; legal rules only affect distribution

Real world: transaction costs exist

Remedy can affect efficiency.

Expectation Damages: Facilitates efficient breach. Promisor chooses cheaper option (perform vs. breach + pay damages), internalizing victim's loss.

Specific Performance: Gives victim strong right. Can lead to inefficient outcomes if bargaining fails due to high transaction costs when performance is costly. (Advantage: Avoids court valuation).

Investment in performance and reliance

remedies influence investments made before breach

promisor’s investment in performance:

💼 Money, time, or effort a party puts in to carry out their part of a contract (e.g. producing goods, preparing services).

👉 It's about doing what you promised.

promisee’s reliance on promise:

🔧 Resources a party spends because they trust the other side will perform (e.g. building a store expecting delivery of goods).

👉 It's about preparing based on the other party's promise.

economic goal: incentivize efficient levels of both

Anticipatory breach

Promisor repudiates contract before performance is due

example: seller announces one month before delivery that van won’t be delivered

issues:

when should damages be calculated

should promisee be compensated for post-repudiation reliance

how does timing affect efficient breach

What is a tort

a civil wrong that causes harm to a person or property

Tortious liability

arises from the breach of a duty primarily fixed by law that is towards persons generally and is redressable by an action for unliquidated damages

types of torts

intentional torts: deliberate acts that cause harm

tort of negligence: harm caused by failure to exercise reasonable care

strict liability torts: liability imposed regardless of fault

Essential elements of a tort claim

breach of duty

harm

causation

Strict liability: only harm and causation required

negligence: all three elements

Types of costs

cost of precaution: expenses incurred to prevent accidents

cost of expected harm: the anticipated monetary value of injuries, property damage, and other losses if an accident occurs

Expected social cost

the sum of the cost of precaution and the cost of expected harm

Minimizing social costs

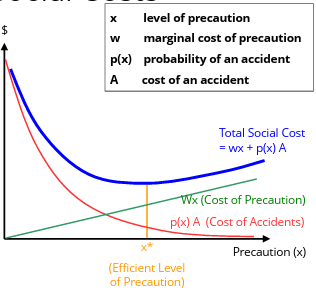

Key elements:

x: Level (amount) of precaution taken to prevent accidents.

w: the cost of each “unit” of precaution

p(x): Probability of an accident occurring, given precaution x

A: Monetary value of harm caused by an accident (if it occurs).

Expected costs

Expected Cost of Accidents: p(x)A

Cost of Precaution: wx

Total Social Cost: p(x)A + wx

Social cost of accidents

Precaution Costs (wx) increase with care

Expected Harm (p(x)A) decreases with care

Total Social Cost (SC = wx + p(x)A)

Efficient Level of Precaution (x*)

Minimizes total expected social costs

Marginal cost = marginal benefit

w=−p′(x*)A

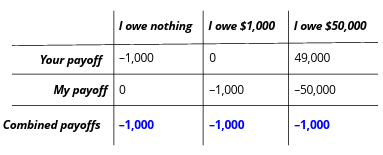

For efficiency, do post-accident events matter?

NO

compensation is just a wealth transfer:

it doesn’t change the total social cost - accident still destroys $1,000 in value and combined payoffs is always -$1,000

Implications:

focus on prevention, not redistribution

liability rules matter for incentives, not post-accident fairness

efficiency requires minimizing total costs, not balancing them

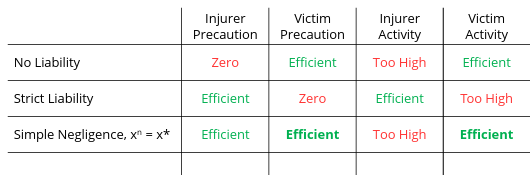

Incentives for precaution and activity levels

No liability:

Injurer: No incentive for precaution or reducing risky activity.

Victim: Strong incentive for precaution and reducing risky activity (bears all costs).

Outcome: Often leads to under-precaution by injurers.

Strict liability:

Injurer: Strong incentive for precaution and reducing risky activity (bears all costs).

Victim: No incentive for precaution (gets fully compensated).

Outcome: Often leads to under-precaution by victims in bilateral settings.

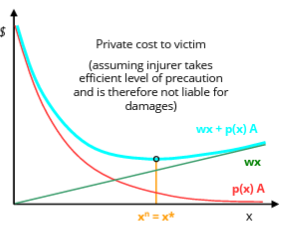

Simple negligence: injurer is liable only if they breached their duty of reasonable care

the injurer is incentivized to choose the level of precaution that minimizes total social costs

the negligence rule aligns private incentives with social efficiency

it encourages injurers to take the right amount of precaution, not too little or too much

What does this mean for the victim?

If the injurer takes efficient precaution (x*), they are not liable under the negligence rule.

Victim bears the costs of any accidents.

Even with optimal precaution, some risk of accidents remains. This is called residual risk.

Bilateral Precaution and Paradox of Compensation

If we try to split the damages (e.g., imperfect compensation), both parties only internalize a portion of the harm cost.

This leads to incentives for deficient precaution by both parties.

Solving the Paradox: The Negligence Rule!

Variations of the negligence rule

simple negligence: injurer liable if negligent

contributory negligence: injurer liable if negligent unless victim also negligent

comparative negligence: liability split based on proportion to fault

strict liability with contributory negligence: injurer strictly liable unless victim negligent

Precaution vs. Activity level

Precaution: how safely you perform an activity

Activity level: how much you engage in a risky activity

Incentives for activity levels

No liability

injurer: not responsible for accident

victim: bears full cost of accident

outcome: inefficiently high level of injurer activity, but efficient level of victim activity

Strict liability

injurer: internalizes cost of accidents

victim: bears no cost of accidents

outcome: efficient level of injurer activity, but an inefficiently high level of victim activity

Simple negligence

injurer: only liable if he was negligent

victim: bears “residual risk”

outcome: inefficient level of injurer activity, but efficient level of victim activity

The Hand rule

Failure to take a precaution constitutes negligence if B < L x P

B: burden of taking precautions (cost of precautions)

L: magnitude of loss/harm (cost of accident)

P: probability of harm (probability of accident)

—> courts can set the legal standard of care (xn) equal to the efficient level of precaution (x*)

Maria inherits a scooter. › Sells it to Noah for €3,000. › Noah spends €150 on protection. › Noah values the scooter at €5,000. › Olivia offers Maria €6,000. Who is the efficient owner of the scooter?

Efficiency maximizes overall benefit - the owner is the one who values it the most

Olivia values it at > €6,000, Noah at €5,000, Maria at < €3,000

Olivia is the efficient owner

Maria inherits a scooter. › Sells it to Noah for €3,000. › Noah spends €150 on protection. › Noah values the scooter at €5,000. › Olivia offers Maria €6,000. If Maria breaches, calculate reliance damages for Noah?

Reliance damages compensate expenses. Reliance damages: €150.

Maria inherits a scooter. › Sells it to Noah for €3,000. › Noah spends €150 on protection. › Noah values the scooter at €5,000. › Olivia offers Maria €6,000. What would the expectation damages be?

Expectation damages compensate lost benefit. Value of scooter to Noah (€5,000) – Price of scooter (€3,000) Expectation damages: €2,000.

Maria inherits a scooter. › Sells it to Noah for €3,000. › Noah spends €150 on protection. › Noah values the scooter at €5,000. › Olivia offers Maria €6,000. Given the remedy of expectation damages, who would own the scooter?

Maria would breach the contract - pay Noah €2,000 in damages - sell to Olivia for €6,000 - Olivia gets the scooter (efficient outcome)

Maria inherits a scooter. › Sells it to Noah for €3,000. › Noah spends €150 on protection. › Noah values the scooter at €5,000. › Olivia offers Maria €6,000. Olivia refuses to buy from Noah; Maria and Noah can't renegotiate; and specific performance is ordered.

Maria sells to Noah (original contract enforced) - Noah gets the scooter - Noah's payoff: €2,000 net benefit - Maria's payoff: €3,000 (or €3,000 minus her value of the scooter)

Emily orders custom sofa › Store orders special fabric › Sofa arrives but Emily dislikes the colour › Store can return sofa to supplier without cost › Store expected significant profit. Emily might back out due to various reasons (financing, job loss, etc.). 80% of buyers best manage these risks, 20% of sellers. What would a majoritarian default rule dictate regarding liability for buyer breach?

🧠 Buyers are usually better at managing their own risk (e.g., job loss, moving).

⚖ So, the default rule puts that risk on the buyer.

🔁 In rare cases (~20%), the seller may be better suited to bear the risk.

📝 Parties can contract around the default, but it increases transaction costs.

💰 If the seller takes on the risk, the price (e.g., of a sofa) will likely be higher to compensate for that added risk.

Homeowner hires contractor to build deck › Agreed price: €6,000 › Homeowner values deck at €8,000 › Second homeowner offers €9,000 for same deck. Who is the efficient owner?

› Efficient owner: Second homeowner, who values it most

› Values: First homeowner: €8,000 Second homeowner: >€9,000 Contractor: <€6,000

Whitewater rafting carries injury risks › Base cost of operating a rafting trip is €150 per person. › Safety measures cost €100 extra per customer › Reduce injury probability from 1/100 to 1/300 › Average injury costs €30,000 › Five potential customers, valuing experience differently § Customer enjoyment values: €500, €400, €300, €200, €100.What is the efficient level of precaution for rafting companies to take (high or low)?

Total Expected Cost: Cost of Precaution + Expected injury cost

Expected injury cost

Without safety measures:

Probability of injury: 1/100

Expected injury cost per person: 1/100 × €30,000 = €300

Operating cost = Base cost + Cost of Precaution = €150 + €0 = €150

Total expected cost: Cost of Precaution + Expected injury cost = €150 + €300 = €450

With safety measures:

Probability of injury: 1/300

Expected injury cost per person: 1/300 × €30,000 = €100

Operating cost: Base cost + Cost of Precaution = €150 + €100 = €250

Total expected cost: €250 + €100 = €350

Thus, it is efficient for the operator to take precaution

Whitewater rafting carries injury risks › Base cost of operating a rafting trip is €150 per person. › Safety measures cost €100 extra per customer › Reduce injury probability from 1/100 to 1/300 › Average injury costs €30,000 › Five potential customers, valuing experience differently § Customer enjoyment values: €500, €400, €300, €200, €100. How many customers should go rafting where benefits outweigh costs?

Social cost of rafting with precaution: €350

Customer valuations:

Customer 1: €500 (efficient)

Customer 2: €400 (efficient)

Customer 3: €300 (inefficient)

Customer 4: €200 (inefficient)

Customer 5: €100 (inefficient)

Efficient activity level: 2 customers

Assume perfect competition in the rafting industry, with many companies and identical costs. The price of rafting is driven down to marginal cost, plus expected liability payments, if any. For (c)-(f), assume customers accurately perceive and consider the injury risk and can observe the precaution level taken by each rafting company. Under no liability, what precaution level will operators take? Why?

The Pricing Dilemma

Low Precaution Option:

Company cost: €150

Price: €150 (due to competition)

Customer perceived cost: €450 (€150 + €300 expected injury cost)

High Precaution Option:

Company cost: €250

Price: €250

Customer perceived cost: €350 (€250 + €100 expected injury cost)

Rational customers will choose the safer option, and companies are incentivized to take high precaution.

Assume perfect competition in the rafting industry, with many companies and identical costs. The price of rafting is driven down to marginal cost, plus expected liability payments, if any. For (c)-(f), assume customers accurately perceive and consider the injury risk and can observe the precaution level taken by each rafting company. Under perfect competition, what will be the price of rafting?

In a perfectly competitive market, the price of a service equals the marginal cost of providing it.

Since operators will take the high precaution level to attract customers, …:

… price of rafting with high precaution: €250

Macroeconomics

deals with the economy as a whole:

aggregate income, consumption, investment, and the overall level of prices

focus on national and international economic performance

Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

The market value of the final goods and services produced within a country’s borders in a given period

How to measure GDP

production approach: market value of all final goods and services produced domestically

expenditure approach: total spending by all economic agents on final goods and services - must subtract imports

GDP (Y) = C + I + G + NX

Y = GDP

C = Consumption expenditure (households)

I = Investment (business)

G = Government Purchases

NX = Net exports (exports minus imports)

What is inflation

A sustained rise in the average price level over time

not just temporary price increases

affects the purchasing power of money

makes comparisons across time difficult

Functions of money

medium of exchange (facilitating trade)

Unit of account (measuring value)

Store of value (measuring value)

Standard of deferred payment (contracts over time)

How is money’s value determined by supply and demand

supply: controlled by central banks

demand: based on economic activity and confidence

key relationship: more money in circulation generally leads to higher prices

How do central banks control money supply?

interest rate policy

bank reserve requirements

government bond purchases and sales

Why might money supply increase?

economic stimulus during recessions

financing government deficits

responding to financial crises

The costs of inflation

price system distortion:

makes it harder to distinguish relative price changes from general inflation

reduces efficiency of market signals

redistribution of wealth

hurts creditors, helps debtors

particularly harmful to those on fixed incomes

planning difficulties

makes long-term contracts and investments risky

interferes with retirement and savings planning

Consumer Price Index

Measures cost of a representative basket of goods and services and compares current cost to base year cost

example:

base year (2010) basket cost: $680

current year (2025) basket cost: $850

CPI = $850/$680 = 1.25 (25% higher than base year)

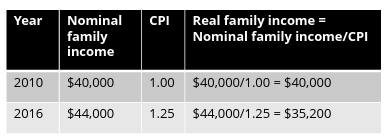

Real vs. Nominal values

Converting nominal to real values: real value = nominal value / price index

Real vs. Nominal Interest Rates

Real interest rate = nominal interest rate - inflation rate

formula: r ≈ i- π

r = real interest rate

i = nominal (market) interest rate

π = inflation rate

example:

bank pays 5% nominal interest

inflation is 3%

real return = 2%