Lab 5: Epidermis

1/13

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

14 Terms

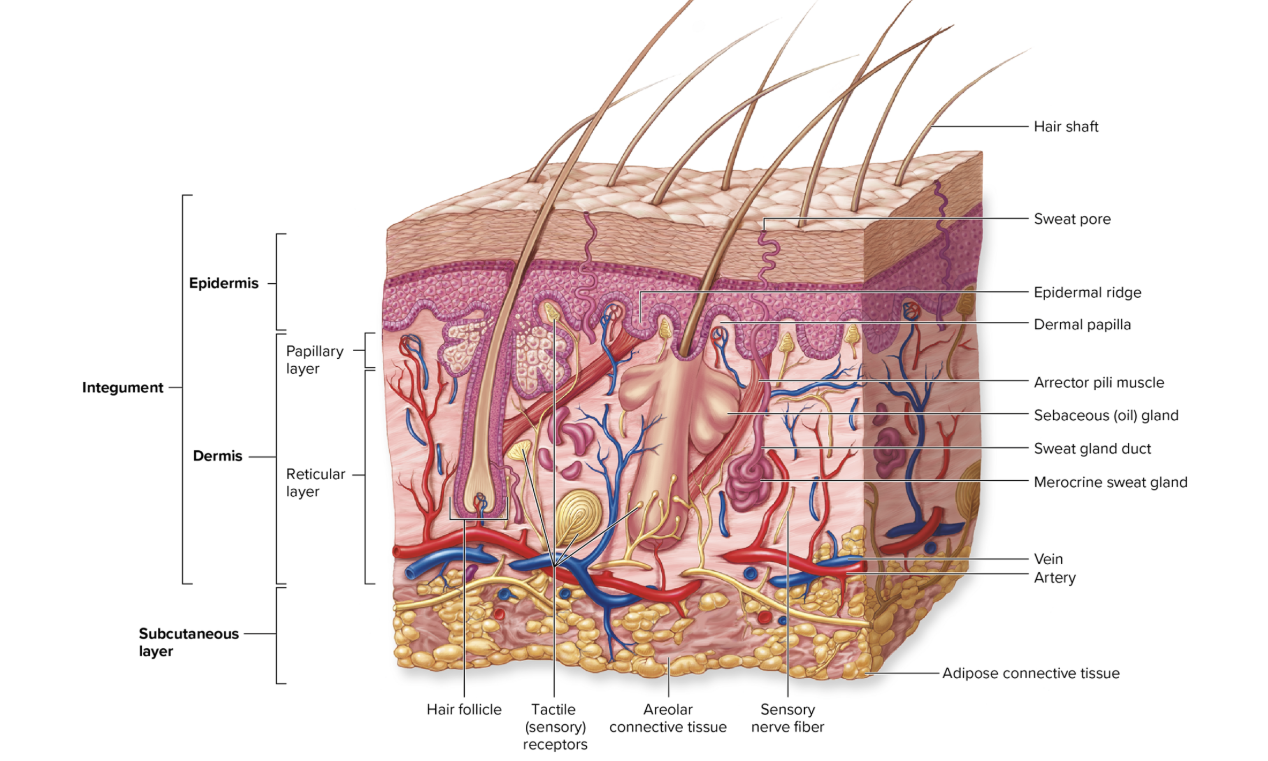

Composition and Functions of the Integument

The integument is the body's largest organ and is composed of all the tissue types that function in concert to protect internal body structures.

Its surface is an epithelium that protects underlying body layers.

The connective tissue that is deep to the epithelium provides strength and resilience to the skin.

This connective tissue also contains smooth muscle associated with hair follicles (arrector pili) that alters hair position.

Finally, nervous tissue within the integument detects and monitors sensory stimuli, thus providing information about touch, pressure, temperature, and pain.

The integument accounts for 7% to 8% of the body weight and covers the entire body surface with an area that varies between about 1.5 and 2.0 square meters (m?).

Its thickness ranges between 1.5 millimeters (mm) and 4 mm or more, depending on body location. (For comparison, a sheet of copier paper is about 0.1 mm thick, so the thickness of the skin would range between 15 and 40 sheets of paper.)

The integument consists of two distinct layers: a layer of stratified squamous epithelium called the epidermis, and a deeper layer of both areolar and dense irregular connective tissue called the dermis

Deep to the integument is a layer of areolar and adipose connective tissue called the subcutaneous layer, or hypodermis.

The subcutaneous layer is not part of the integumentary system; however, it is described in this chapter because it is closely associated with both the structure and function of the skin

Epidermis

The epithelium of the integument is called the epidermis (ep-i-derm'is; epi = on, derma = skin). It is a keratinized, stratified squamous epithelium

While the entire integument thickness ranges from 1.5-4 mm, the thickness of only the epidermis ranges between 0.075 mm and 0.6 mm.

Careful examination of the epidermis, from the basement membrane to its surface, reveals several specific layers, or strata.

From deep to superficial, these layers are:

stratum basale

stratum spinosum

stratum granulosum

stratum lucidum (found in thick skin only)

stratum corneum

The first three strata listed are composed of living cells, whereas the most superficial two strata contain dead cells.

Stratum Basale

The deepest epidermal layer is the stratum basale (strat'um bah-sa'le), also known as the stratum germinativum, or basal layer.

This single layer of cuboidal to low columnar cells is tightly attached by hemidesmosomes to an underlying basement membrane that separates the epidermis from the connective tissue of the dermis.

Three types of cells occupy the stratum basale

Keratinocytes

Melanocytes

Tactile cells, also called Merkel cells

Keratinocytes

(ke-ra'ti-nö-sit; keras = horn) are the most abundant cell type in the epidermis and are found throughout all epidermal strata.

The stratum basale is dominated by large keratinocyte stem cells, which divide to generate new keratinocytes that replace dead keratinocytes shed from the surface.

Their name is derived from their synthesis of keratin, a protein that strengthens the epidermis considerably.

Keratin is one of a family of fibrous structural proteins that are both tough and insoluble. Fibrous keratin molecules can twist and intertwine around each other to form helical intermediate filaments of the cytoskeleton.

The specific type of keratin proteins found in keratinocytes are called cytokeratins.

Their structure in these keratinocytes gives skin its strength and makes the epidermis water resistant.

Melanocytes

(mel'ă-nõ-sit; melano = black) have long, branching processes and are scattered among the keratinocytes of the stratum basale. T

hey produce and store the pigment melanin (mel'ă-nin) in response to ultraviolet light exposure.

Their cytoplasmic processes transfer melanin pigment within organelles called melanosomes (mel'ă-no-somes) to the keratinocytes within the basal layer and sometimes in more superficial layers.

This pigment (which includes the colors black, brown, tan, and yellow-brown) accumulates around the nucleus of the keratinocyte and shields the nuclear DNA from ultraviolet (UV) radiation.

The darker tones of the skin result from melanin produced by the melanocytes. Thus, "tanning" is the result of the melanocytes producing melanin to block UV light from causing mutations in the DNA of your keratinocytes (in the epidermis) and fibroblasts (in the dermis).

Tactile cells, also called Merkel cells

are few in number and found scattered among the cells within the stratum basale.

Tactile cells are sensitive to touch and, when compressed, they release chemicals that stimulate sensory nerve endings.

These cells are more common in the stratum basale in sensitive areas of the skin, such as the fingertips

Stratum Spinosum

Several layers of polygonal keratinocytes form the stratum spinosum (spi-no'sum), or spiny layer.

Each time a keratinocyte stem cell in the stratum basale divides, the new cell is pushed toward the external surface, while the other cell remains as a stem cell in the stratum basale.

Once this new cell enters the stratum spinosum, it begins to differentiate into a nondividing, highly specialized keratinocyte.

The keratinocytes in the stratum spinosum attach to their neighbors by many membrane junctions called desmosomes, which serve to provide structural support between cells of the epidermis.

The process of preparing epidermal tissue for observation on a microscope slide shrinks the cytoplasm of the cells in the stratum spinosum.

Because the cytoskeleton and desmosomes remain intact, the shrunken keratinocytes in the stratum spinosum resemble miniature porcupines that are attached to their neighbors. This spiny appearance accounts for the name of this layer.

In addition to the keratinocytes, the stratum spinosum also contains the fourth epidermal cell type, called epidermal dendritic (Langerhans) cells.

Epidermal dendritic cells are immune cells that help fight infection in the epidermis.

These immune cells are often present in the stratum spinosum and stratum granulosum, but they are not identifiable in standard histologic preparations

. Their phagocytic activity initiates an immune response to protect the body against pathogens that have penetrated the superficial epidermal layers as well as epidermal cancer cells

Stratum Granulosum

The stratum granulosum (gran-ü-lö'sum), or granular layer, consists of three to five layers of keratinocytes superficial to the stratum spinosum.

Within this stratum begins a process called keratinization (ker'ätin-iza'shun), where the keratinocytes synthesize significant amounts of the protein keratin.

(The granules seen in this layer contain proteins that will help aggregate the keratin filaments in the stratum corneum.)

This accumulation of keratin causes both the nucleus and the organelles of these cells to disintegrate, which ultimately results in the death of these cells.

Keratinization is not complete until the keratinocytes reach the more superficial epidermal layers.

A fully keratinized cell is dead (because it has neither a nucleus nor organelles), but it is structurally strong because of the keratin it contains.

Stratum Lucidum

The stratum lucidum (Iü si-dum), or clear layer, is a thin, translucent region of about two to three keratinocyte layers that is superficial to the stratum granulosum.

This stratum is found only in the thick skin within the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet.

Keratinocytes occupying this layer are flattened, pale cells with indistinct boundaries. They are filled with the translucent protein called eleidin (e-le'i-din), which is an intermediate product in the process of keratin formation.

This layer helps protect the skin from ultraviolet light.

Stratum Corneum

The stratum corneum (kor'ne-um; corneus = horny), or hornlike layer, is the most superficial layer of the epidermis. It is the stratum you see when you look at your skin.

The stratum corneum consists of about 20 to 30 layers dead, scaly, interlocking, keratinized cells.

The dead keratinocytes are anucleate (lacking a nucleus) and are tightly packed together.

The keratinized, or cornified, cells of the stratum corneum layer contain large amounts of keratin.

After keratinocytes are formed from stem cells within the stratum basale, they change in structure and in their relationship to their neighbors as they progress through the different strata until they eventually reach the stratum corneum and are sloughed off its external surface.

Major changes during keratinocyte migration include synthesis of keratin and loss of the nucleus and organelles as described.

What remains of these keratinocytes in the stratum corneum is essentially keratin protein enclosed in a thickened plasma membrane.

(The thickening of the plasma membrane is due to a coating of lipids, which helps form the water barrier in the epidermis.)

Migration of the keratinocyte to the stratum corneum occurs during the first 2 weeks of the keratinocyte's life.

The dead, keratinized cells usually remain for an additional 2 weeks in the exposed stratum corneum layer, providing a barrier before they are shed.

Overall, individual keratinocytes are present in the integument for about 1 month following their formation.

The stratum corneum presents a thickened surface unsuitable for the growth of many microorganisms.

Additionally, some exocrine gland secretions (e.g., sweat, which contains demicidin, an antimicrobial peptide) help prevent the growth of microorganisms on the epidermis, thus supporting its barrier function

Variations in the Epidermis

The epidermis exhibits variations between different body regions within one individual as well as differences between individuals. The epidermis varies in its thickness, coloration, and skin markings.

Thick Skin Versus Thin Skin

Although the skin ranges in thickness from 1.5 mm to 4 mm (see (- section 6.1), its thickness over most of the body is between 1 mm and 2 mm.

However, skin is classified as either thick or thin based on the number of layers and thickness of the stratified squamous epithelium only, rather than the thickness of the entire integument

Thick skin

is found on the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet. All five epidermal strata occur in the thick skin.

The epidermis of thick skin is between 0.4 mm and 0.6 mm thick. It houses sweat glands but has no hair follicles or sebaceous (oil) glands.

Thin skin

Thin skin covers most of the body.

It lacks a stratum lucidum, so it has only four specific layers in the epidermis.

Thin skin contains the following structures: hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and sweat glands. The epidermis of thin skin is between 0.075 mm to 0.150 mm thick.