developmental psychology ch5

1/40

Earn XP

Description and Tags

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

41 Terms

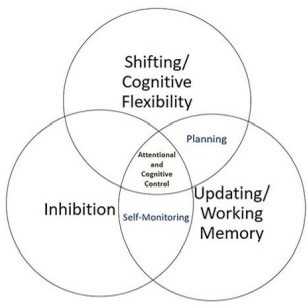

Executive functions:

Higher cognitive functions, an umbrella term for cognitive skills guiding goal directed behaviour.

Cognitive flexibility/Shifting

Inhibition

Updating

Frontal lobe responsibilities and functions

Abstract Thinking

Problem Solving

Reasoning

Executive Functioning

Organizing

Motor Functions

Regulates Emotions

Expressive language

Functions:

Organises thoughts on paper

Remembers and completes tasks

Tells stories

Cognitive flexibility/Shifting:

Two task sets, task is to switch between those.

Example: Is the number presented < 5 or not vs is it even or odd

3 and 4 year olds can shift between two simple, contextualised response sets.

Between 5 and 6 years further improvement in more complex shifting tasks - generalising rules to new, unseen objects.

With increasing age until early adolescence, steady increase in proportion of children who master complex shifting tasks

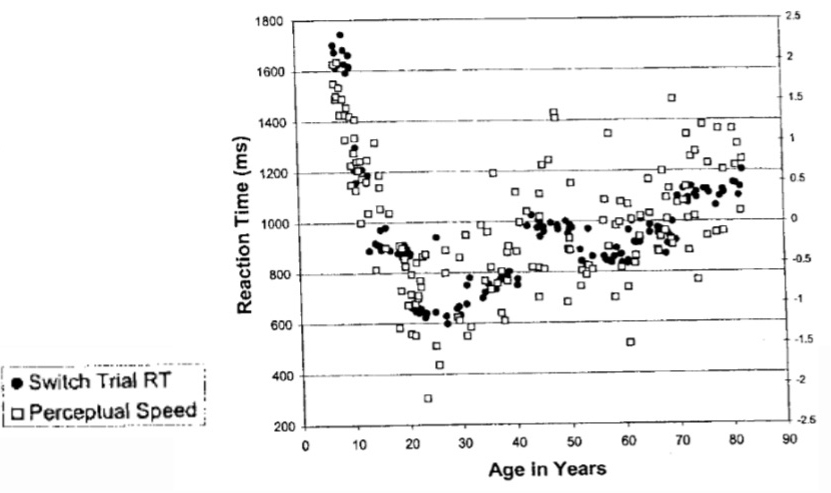

Shift cost:

=difference between shift and non shirt trials. Great for 7 and 11 yr olds than for 15yr olds, those are comparable to young adults.

Speed-accuracy trade off: slowing down to enhance accuracy: more noticeable across childhood → emerging presence of metacognition

In older age, marked age-related decline: higher shift costs.

Executive functions - Inhibition;

a) Motor inhibition - ex. dancing and stoping when the music stops

b) Oculomotor inhibition: Flanker tasks: “respond to direction of arrow in center”

c) Simple response inhibition tasks: “press key if background is green, but don’t press if the background is red”

d) Cognitive inhibition: Stroop task - “Name the colour of the word”

Inhibition: Development

Early childhood: rapid improvements → first signs

Preschool years: significant reduction of inhibition errors - significant improvement between 5-8 yrs

Middle childhood: continued improvements on a) motor inhibition, b) occulomotor inhibition and c) simple response inhibition

Adolescence and adulthood: little further improvement, continued improvement on oculomotor and response inhibition tasks until 15 yrs and until age 21 on d) cognitive inhibition

In aging: decline in response inhibition, no age related decline in oculomotor/cognitive inhibition

→ Fundamental changes during preschool, refinements in speed and accuracy in school age and adolescence, differential effects in aging

Short-term Memory Span:

= Passive short term storage: Retaining information for up to 30 seconds without rehearsal of information → longer retention with rehearsal

Short-term memory: Development

In childhood: very limited capacity → increases during childhood from about to digits in 2/3 year olds to five digits in 7 year olds.

→ Between 7 and 12 years increases by 1.5

In older age: older adults retain about 90% of the elements that younger adults can retain - only small age-related decline, much bigger for WM

Working Memory Model:

= Active short-term memory storage: systems that keep things in mind while performing complex tasks like reasoning, comprehension and learning

Certain overlap with EFs (updating)

Working Memory Model: Development in kids

Complexity of WM task effects trajectories of WM development: easier WM tasks are mastered before more complex ones

Young preschool children: can hold a couple of items in mind simultaneously, developmental differences emerge only by increasing the memory load.

Slow development: by age 8 children can only hold half the items that adults can remember in memory.

Children who have better working memory are more advanced in…

Language comprehension

Math skills

Problem solving

Working Memory Model Development in Adolescence

Further brain maturation → greater functional use of working memory, information processed quicker + simultaneous processes

→ 13 year olds with greater working memory ability show better performance on a variety of academic subjects

→ Lower working memory associated with impulsivity and adolescent alcohol use

Working Memory Model Development in Adults and Elderly

WM capacity diminishes with age.

Disagreement on peak: After 20s or around 45 years

In aging, WM capacity predicts performance on a range of cognitive tasks:

Long-term memory

Problem-solving

Tests of intelligence

What does long term memory consist of?

Explicit (declarative):

→ Episodic (events) → Autobiographical

→ Semantic (facts, general knowledge)

Implicit (nondeclarative):

→ Skills, procedures, habits (Procedural/Motor)

→ Priming

→ Other (ex. classical conditioning, habituation)

LTM - Procedural memory:

Implicit memory develops earlier in infancy than explicit memory: Infants as young as 2.5 months can retain information from being conditoned

Implicit memory capacity changes little across the lifespan: Young children do no worse than older children, older adults often do no worse than young adults

→ Young and old alike learn and retain a lot of information from their everyday experience without any effort, with advancing age affected by biological decline

LTM - Semantic memory:

Growth during childhood as a function of a child’s exposure to information → environment context, acculturation, social status, schooling

Preserved with age - Even expansion in some areas (vocabulary, historical facts):

→ Knowledge and skills learned long time ago persistent for long period of time - permastore, but older adults have difficulties with tip of the tounge etc.

→ Older adults show difficulties when semantic information needs to be accessed rapidly and according to arbitrary rules

LTM - Episodic memory in young childhood

Development starts with hippocampus maturation (second half od 1st year).

Across second year: substantial improvements.

6 months olds can remember information for 24 hours, but by 20 months of age infants can remember information they encountered 12 months earlier.

Still, most conscious memories of young infants are fragile and short-lived. From 3 to 5 years, children remember more events with time and location and remember more detail.

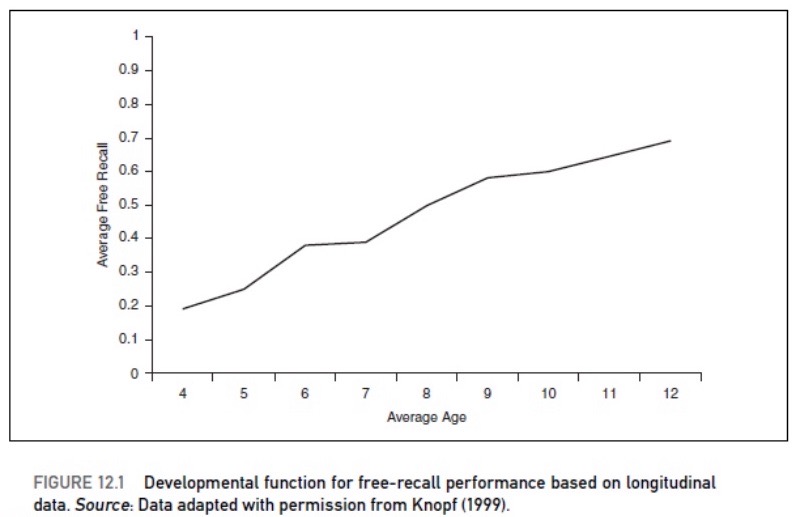

LTM - Episodic memory in older children

During preschool years, young children increasingly remember more autobiographical characteristics → in some areas reasonable good memories

They improve even more in middle and late childhood - advancements in memory strategies.

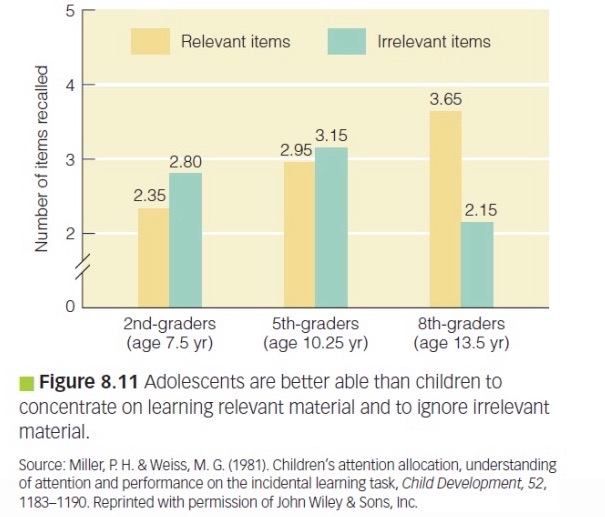

Episodic memory - Adolescents

Episodic memory performance of young teens similar to children, worse than adults.

New memory strategies during adolescence: Memory elaboration strategy is mastered

Advanced learning/memory strategies for school.

Deliberate and selective strategy use.

Memory - Strategies:

Use of mental activities to improve processing of information, not much used by preschool children, but older children and adults.

Use increases gradually:

Rehearsal: beneficial for STM

Organisation: beneficial for LTM - imaginary and verbal information

Elaboration on the information to be remembered and making it personal relevant: beneficial for LTM

Encoding and retrieval: Aging

Relatively stable in middle adulthood

Declines steading throughout older years.

Magnitude of the decline depends on the nature and method of task:

Retrieval vs type of memories.

Performance level: Recognition > Cued Recall > Free recall

Age differences mostly in recall, not recognition.

Age differences recognising paired objects, not old faces and names (unpaired).

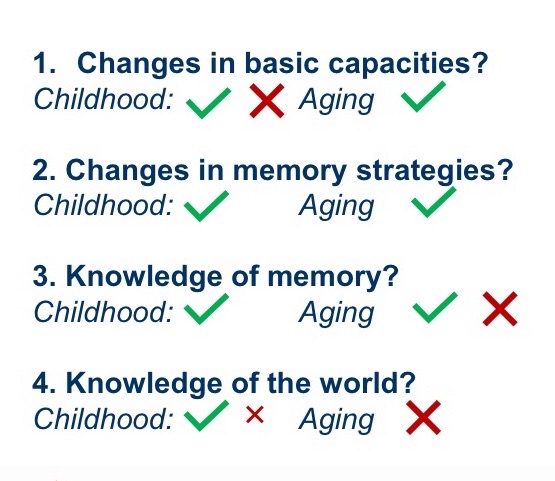

Memory mechanisms underlying change: 4 hypotheses why learning and memory improve/decline

Change in basic capabilities (hardware): WM space for manipulating and processing info

Changes in memory strategies (software): Effective methods for storing/retrieving

Knowledge of memory: Results in selecting appropriate strategies to learn

Knowledge of the world: To be learned material more familiar → easier to learn and remember

Mechanisms - Change in basic capacities: ChildhoodChildhood:

→ Not much change in sensory register and storage capacity of LTM

Encoding improves as PFC, medial temporal lobe mature and hippocampus develop.

Speed of mental processes improves → allows to simultaneously perform more mental operations in WM.

Mechanisms - Change in basic capacities: Older age→ Decline in sensory abilities strains available processing resources.

Not much change in STM, but in WM (PFC related)

Inhibition deficit

Slower functioning of the nervous system - reduced speed of processig.

Mechanisms: Changes in memory strategies: Childhood

→ More strategy usage when goal is personally relevant and remembering instructed, gradual development.

Young children (<4 yrs): perservation errors → stick to old strategy

Despite knowledge on strategies, deficient spontaneous use.

Mechanisms: Changes in memory strategies: Older age

→ Many older adults don’t spontaneously use strategies.

When prompted to use one, improved memory performance - bigger effect for high intelligence.

Correct strategy implementation = positive effect of strategy training.

Mechanisms: Knowledge of memory - Childhood

Metacognitive awareness present in early form at young age, improves throughout.

Children with greater metamemory awareness = better memory ability.

Good metamemory no guarantee of good recall, must be motivated.

Development continues in adolescence: only 50-60% plan for difficult tasks, but 80% monitor performance during task.

Mechanisms: Knowledge of memory - Older age

Metacognitive knowledge maintained.

Able to monitor memory, but misjudge accuracy.

Negative beliefs about their memory skills → age stereotypes.

Mechanisms - Knowledge of the world: Childhood

Adults outperform children, but age difference could be reversed if kids had more expertise than adults.

Older kids controlling familiarity of material and young adults still perform better than young kids.

→ Memory improvements not solely attributable to greater knowledge base.

Mechanisms - Knowledge of the world: Older age

At least as knowledgeable as adults + further improvements.

→ Knowledge not source of memory problems, rather help to compensate.

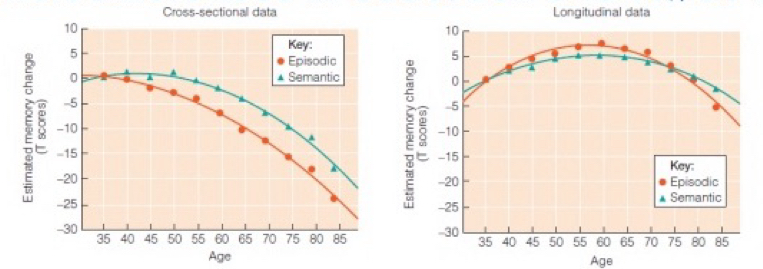

Memory ability change: Summary

Methodological considerations: Cross-sectional vs Longitudinal assessment of cognition

Cross-sectional data confirms lower performance with older age.

Opposite patterns for cross-sectional and longitudinal assessments.

Longitudinal improvements at least party explained by test-retest.

Contextual factors in aging:

Biological and genetic factors + environmental and situational factors.

Characteristics of the learner

Characteristics of the task or situation

Characteristics of the broader environment, including cultural context.

Cohort differences in education and IQ as well as health and lifestyle.

In familiar context often high performance, but not laboratory.

Contextual factors in aging: Prospective Memory

= memory for intentions.

Age-prospective memory paradox:

YA > OA in lab

OA < YA in real life

Cognitive functioning in older age - general patterns:

High functioning if: Routines and habits, supporting external cues, access to prior knowledge, clear structure provided

Problems might occur if: new situations, time pressure, several goals followed at the same time, tired or distracted, senses or body deplete resources.

Inter-individual differences (variability):

In addition to mean age trends - important variations within age groups. Wide individual differences within age groups and distribution overlap.

Protection and Resilience: A multisystem approach

Is it possible to minimise or slow down decline?

Yes - adaptive lifestyle, modifiable psychosocial and behavioural factors and interventions. Can reduce risk for decline and disease.

Risk factors: Smoking, poor diet, obesity, loneliness

Protective factors: Engaged lifestyle, physical exercise, social support, positive beliefs, sense of control.

Mulifactorial background for age-related variability

Protection and Resilience: Incident Alzheimer’s disease

Low educational attainment and smoking increase relative risks for incident Alzheimer’s disease.

Physical activity shows protective effects.

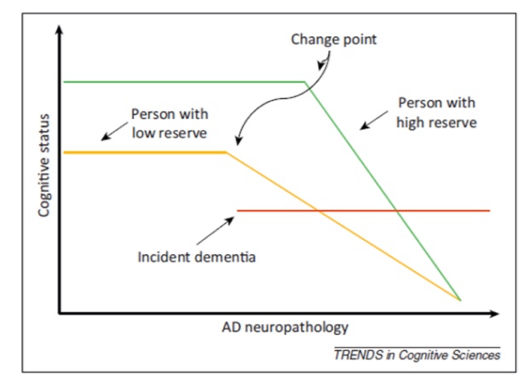

Cognitive reserve:

=Cummulative enhancement of neural resources based on genetic and or environmental factors: helping to mitigate the effects of decline caused by aging/age-related diseases.

Ideal: Reserve counteracts aging fully.

Typical: Only attenuates.

Cognitive reserve can continue to accumulate in older age.

Striking inter-individual variability: In cross-sectional studies some 80 year olds perform better than 40 year olds on cognitive tasks impaired by aging.

What is cognitive reserve, what shapes it, and how does it affect cognitive decline?

Cognitive reserve is shaped by cognitive exposures/activities across the lifespan, including:

Years of education

Crystallized intelligence (knowledge)

Occupational complexity

Intellectually stimulating leisure activities

Socioeconomic status

It acts as a buffer for cognitive decline:

Low cognitive reserve → earlier and faster decline, earlier signs of pathology (e.g. Alzheimer’s)

High cognitive reserve → later decline, but typically steeper once reserve is depleted