AP Art History 250 Required Images

1/124

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

125 Terms

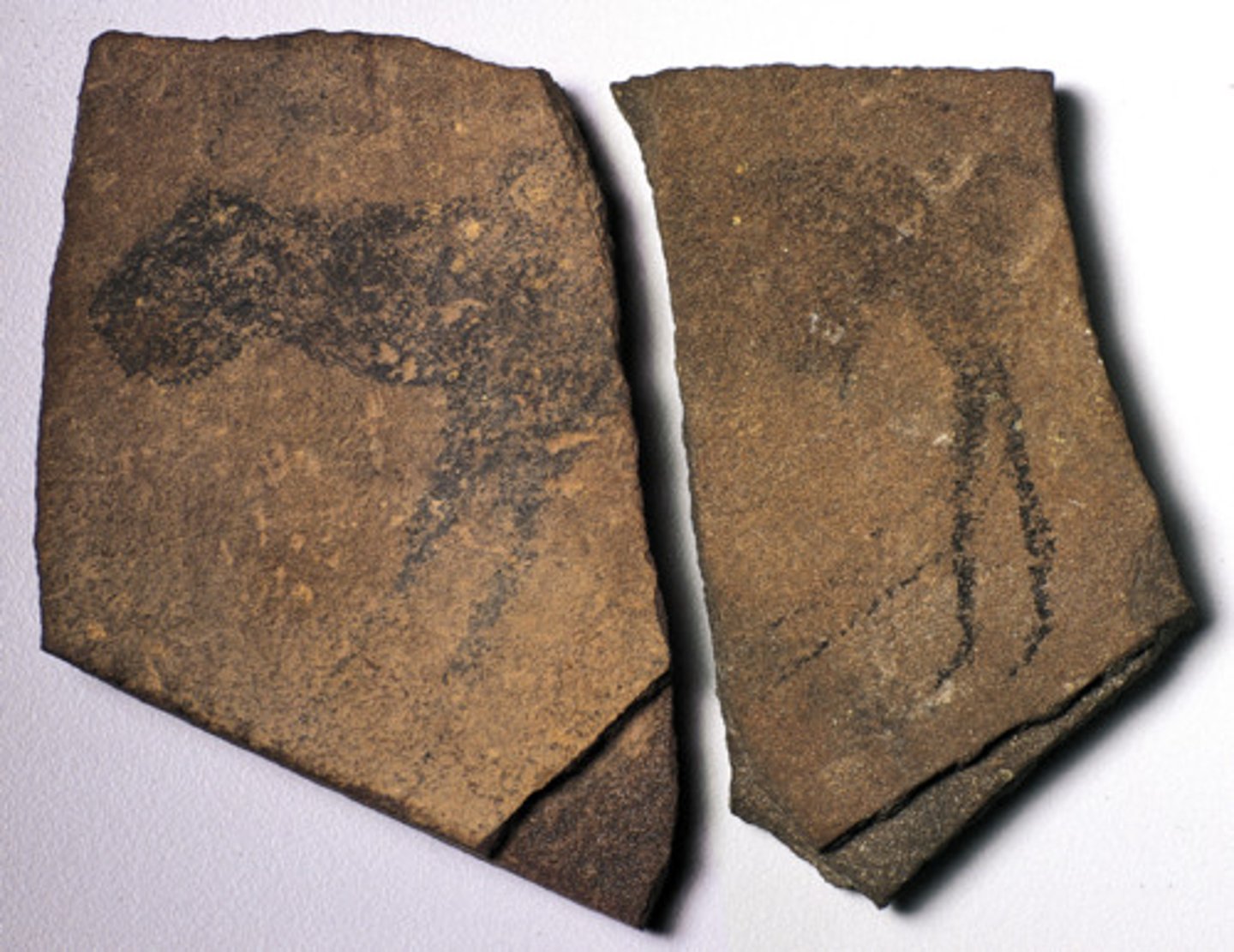

Apollo 11 Stones

Nambia. c. 25000-25300 B.C.E. Charcoal on stone

The earliest history of rock painting and engraving arts in Africa. The oldest known of any kind from the African continent.

Great Hall of Bulls

Lascaux, France. Paleolithic Europe. 15000-13000 B.C.E. Rock Painting

represents the earliest surviving examples of the artistic expression of early people. Shows a twisted perspective.

Camelid sacrum in the shape of a canine

Tequixquiac, central Mexico. 14000-7000 B.C.E. Bone.

The shape was created by using subtractive techniques and utilizing already apparent features in the bone, like the holes for eyes. It was a first look at how people began manipulating their environment to created what they wanted.

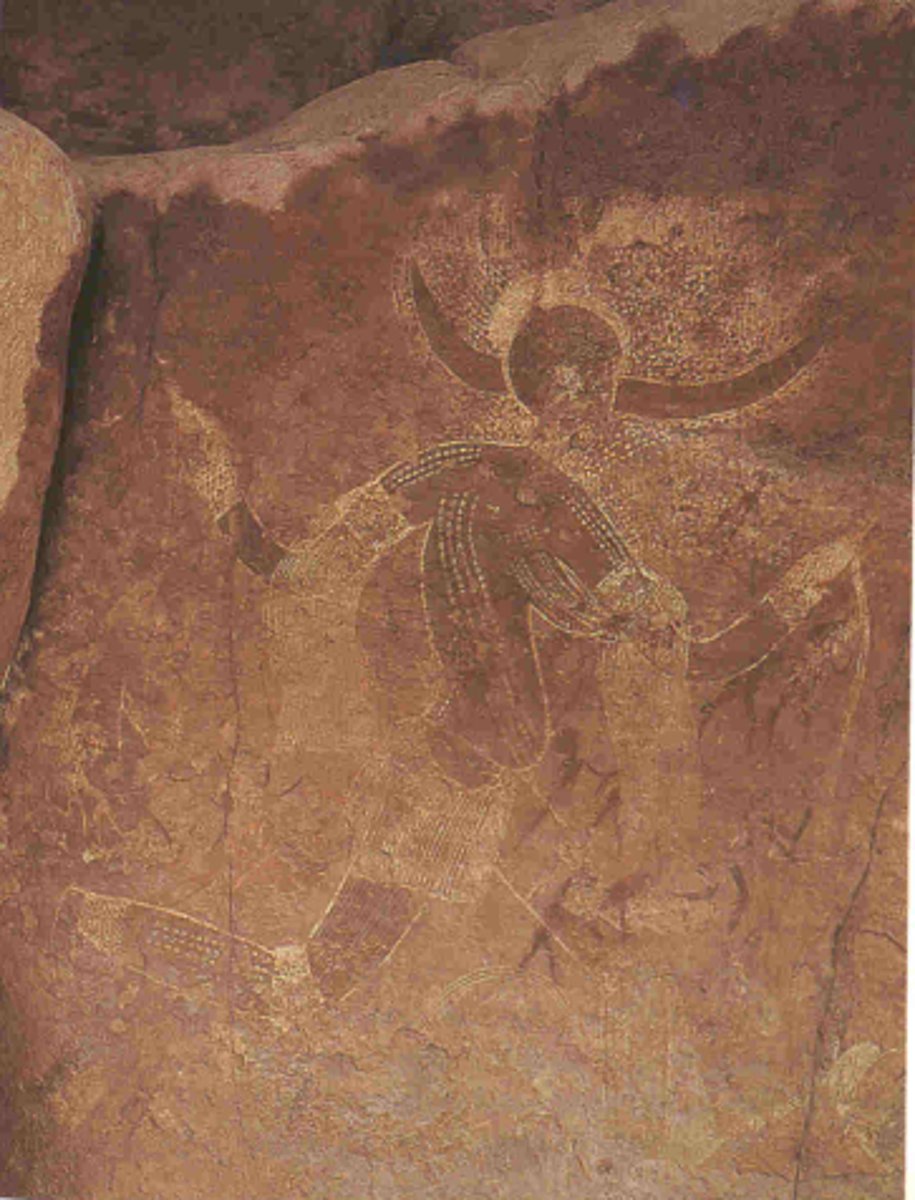

Running horned women

Tassili n'Ajjer, Algeria. 6000-4000 B.C.E. Pigment on rock.

The painting shows great contrast between the dark and light mediums used. There is also great detail put into the decorations of the woman. Most interestingly, though, there is a transparency to the larger woman and the figures behind her show through.

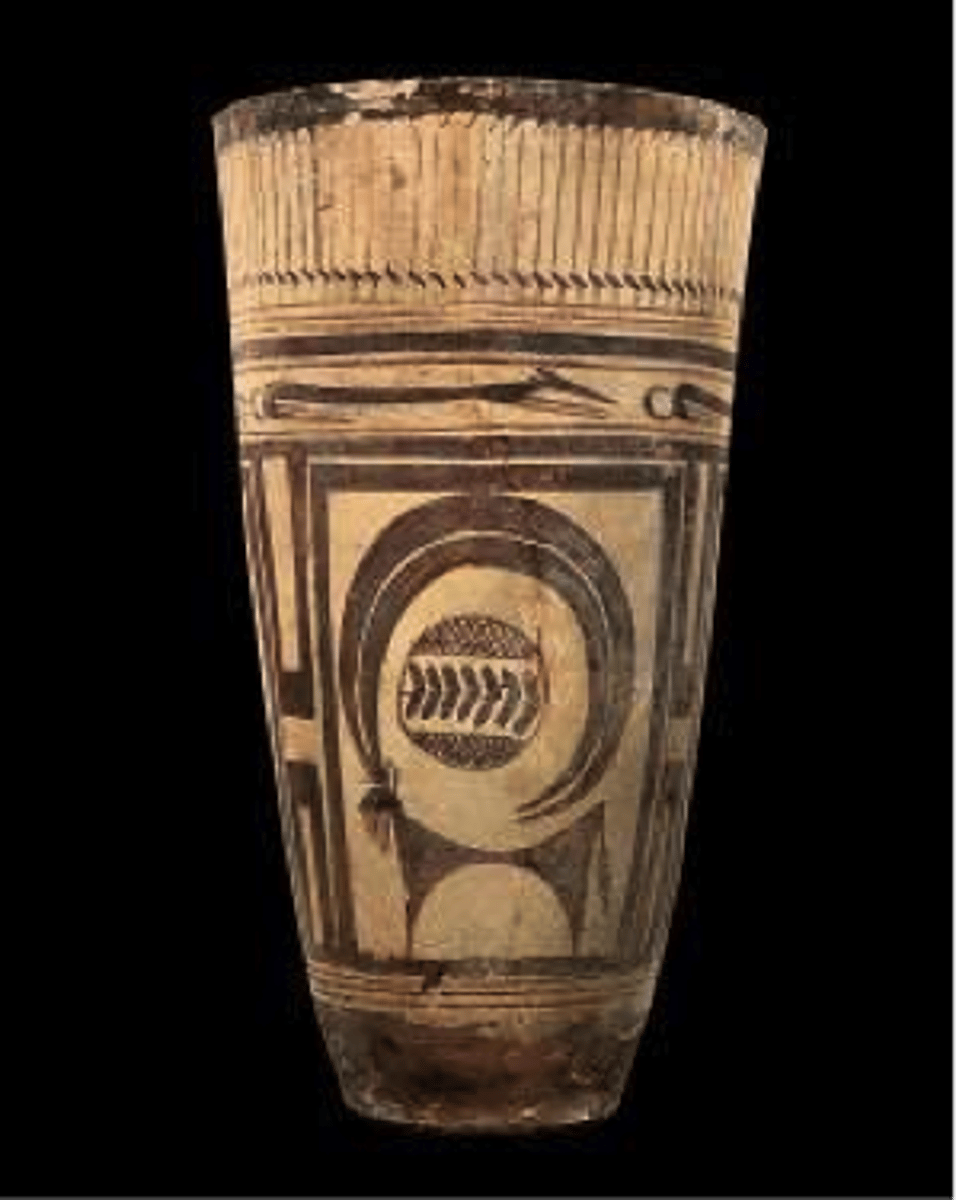

Beaker with ibex motifs

Susan, Iran. 4200-3500 B.C.E. Painted terra cotta.

One of the first ceramic pieces, made from clay and intricately designed with mineral and plant paint in painstaking detail. The vessel portrays a Ibex, a type of goat native to the area, and also canine figures along the rim. At the time, dogs were used to hunt animals like Ibexes. The painting might have been done with small brushes made from plant material or human or animal hair

Anthropomorphic stele

Arabian Peninsula. Fourth millennium B.C.E. Sandstone.

Very stylized representation of a human figure, carved from stone. Has a make image and carries knives in sheaths across the chest and a knife tucked into a belt.

Jade cong

Liangzhu, China. 3300-2200 B.C.E. Carved jade.

Like one of many, this was a jade piece with decorative carvings, unique shape, and symbolic purpose. The stone might have held spiritual or symbolic meanings to the early cultures of China.

Stonehenge

Wiltshire, U.K. Neolithic Europe. c. 2500-1600 B.C.E. Sandstone

Stonehenge is a famous site know for its large circles of massive stones in a seemingly random location as well as the mystery surrounding how and why it was built. The stones are believed to be from local quarries and farther off mountains. There is also evidence of mud, wood, and ropes assisting in the construction of the site.

The Ambum Stone

Ambum Valley, Enga Province, Papua New Guinea. c. 1500 B.C.E. Greywacke

This is a sculpture of some sort of anteater-like creature made from a very rounded stone. With intense use of subtractive sculpting, this piece achieves a freestanding neck and head while still maintaining much of the original shape of the stone. It still uses natural materials and depicts a natural animal.

Tlatilco female figurine

Central Mexico, site of Tlatico. 1200-900 B.C.E. Ceramic

The piece also stands as foreshadowing of the great civilizations that develop in south and meso-america and the art that is produced.

Terra Cotta Fragment

Lapita. Solomon Islands, Reef Islands. 1000 B.C.E. Terra cotta (incised)

One of the first examples of the Lapita potter's art, this fragment depicts a human face incorporated into the intricate geometric designs characteristics of the Lapita ceramic tradition.

White Temple and its Zuggurat

Uruk (modern Warka, Iraq). Sumerian. c. 35000-3000 B.C.E. Mud Brick.

Rooms for different functions. Cella (highest room) for high class priests and nobles.

Very geometric (4 corners of structure facing in cardinal directions) Platform stair stepped up

Palette of King Narmer

Pre-dynastic Egypt. c. 3000-2920 B.C.E Greywacke

Egyptian archelogical find, dating from about the 31st century B.C, containing some of the earliest hieroglyphic inscription ever found.

Statue of Votive figures from the Square Temple at Eshnunna

Sumerian. c. 2700 B.C.E. Gypsum inland with shell and black limestone

Surrogate for donor and offers constant prayer to deities. Placed in the Temple facing altar of the state gods

Seated Scribe

Saqqara, Egypt. Old Kingdom, Fourth Dynastic. c. 2620-2500 B.C.E. Painted limestone. the sculpture of the seated scribe is one of them most important examples of ancient Egyptian art because it was one of the rare examples of Egyptian naturalism, as most Egyptian art is highly idealized and very rigid.

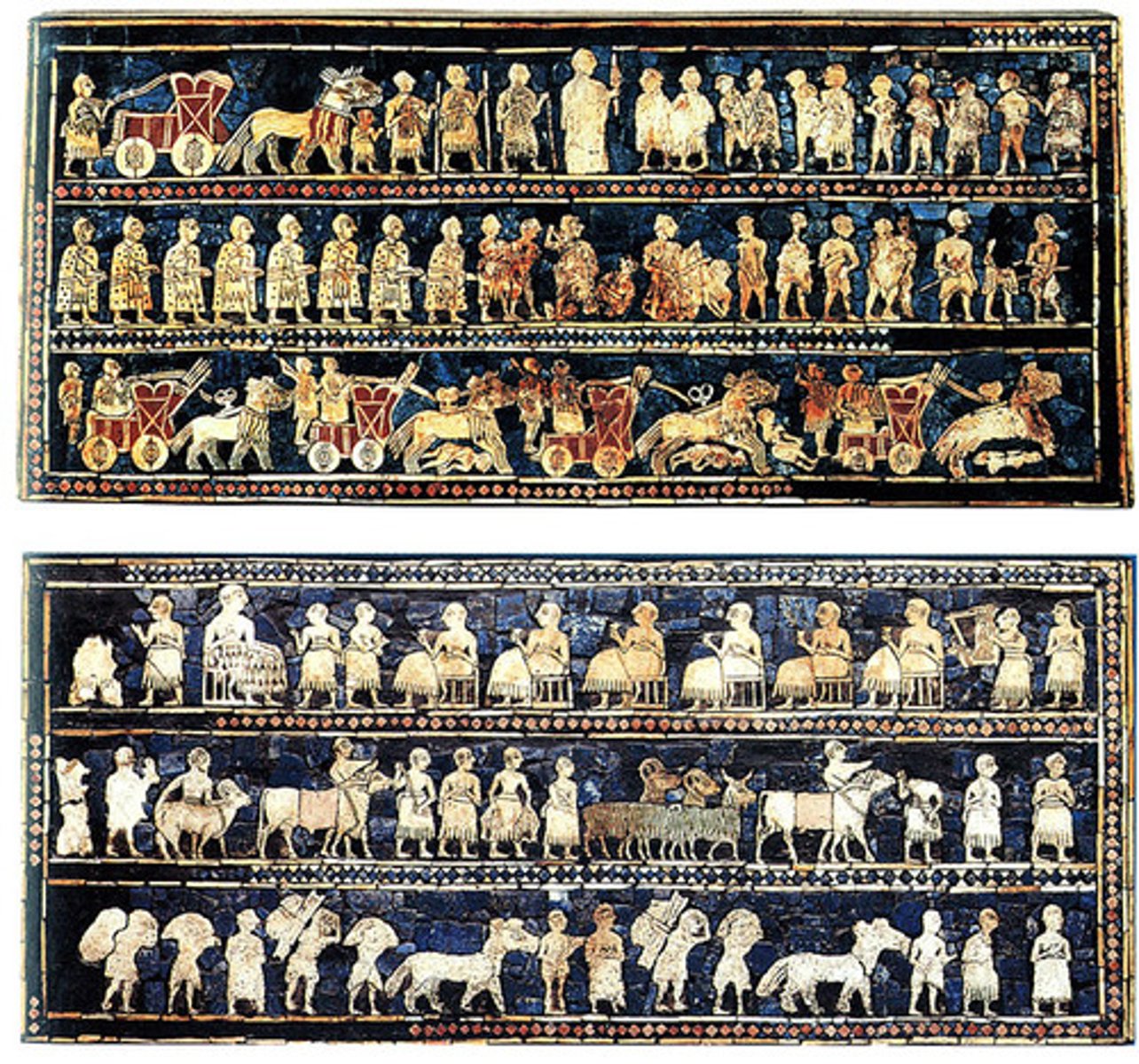

Standard of Ur from the royal tombs

Summerian. c. 26000-24000 B.C.E. Wood inlaid with shell, lapis, lazuli, and red limestone.

Found in one of the largest graves in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, lying in the corner of a chamber above a soldier who is believed to have carried it on a long pole as a standard, the royal emblem of a king.

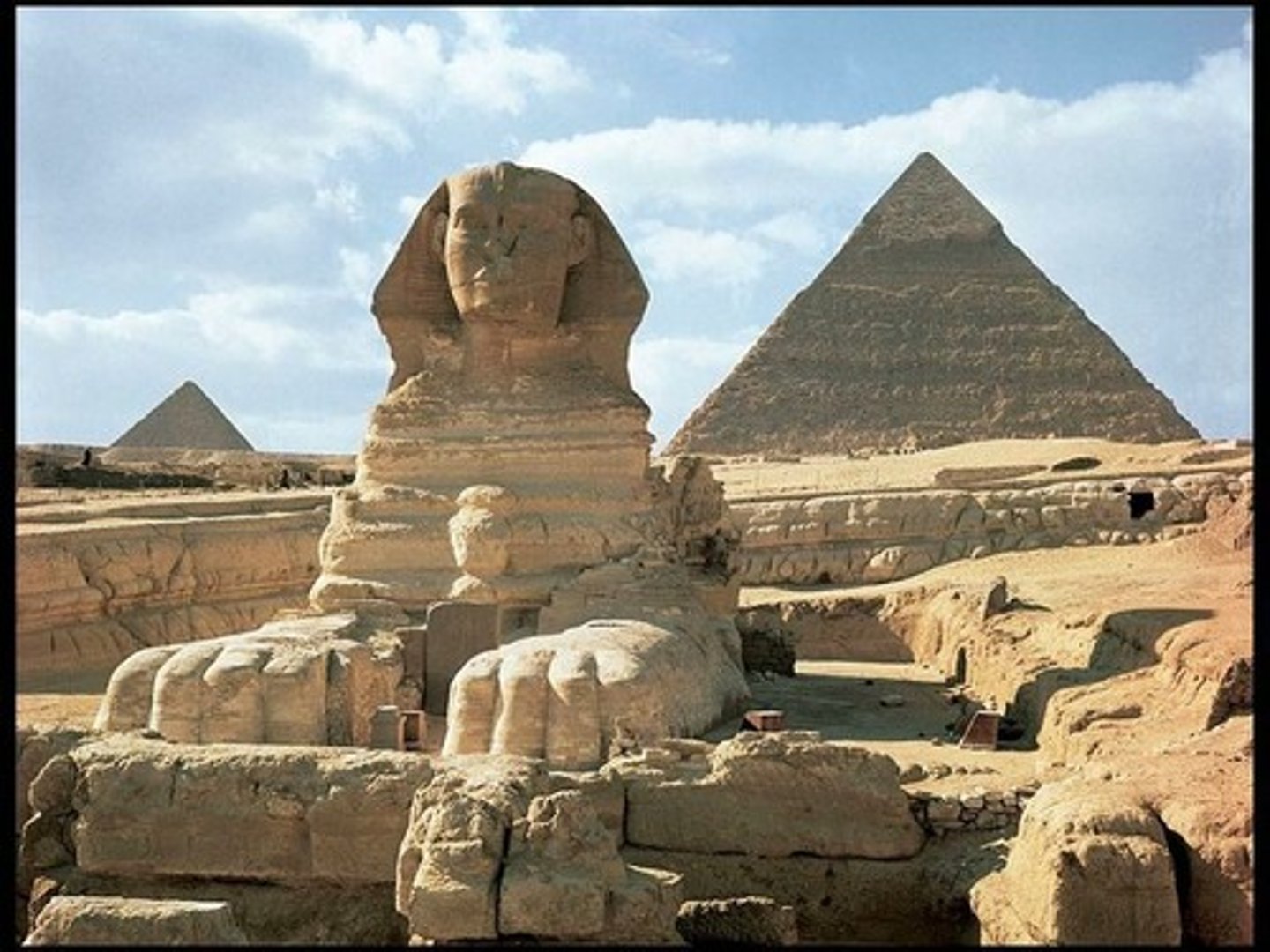

Great Pyramids (Menkaura, Khafre, Khufu) and Great Sphinx

Giza, Egypt. Old Kingdom, Fourth Dynasty. c. 2550-2490 B.C.E. Cut limestone.

The Great Sphinx is believed to be the most immense stone sculpture ever made by man.

(stone, tombs, statues, animal symbolism)

The code of Hammurabi

Babylon (modern Iran). Susain. c. 1792-1750 B.C.E. Basalt.

In this stone is carved with around 300 laws, the first know set of ruler enforced laws.

(Stone, carved, laws, inscriptions)

Temple of Amun-re and Hypostyle Hall

Karnark, near Luxor, Egypt. New Kingdom, 18th and 19th Dynasties. Temple: c. 1550 B.C.E.; hall: c. 1250 B.C.E. Cut sandstone and mud brick.

The Hypostyle Hall is also the largest and most elaborately decorated of all such buildings in Egypt and the patchwork of artistic styles and different royal names seen in these inscriptions and relief sculptures reflect the different stages at which they were carved over the centuries. As the temple of Amun-re is the largest religious complex in the world.

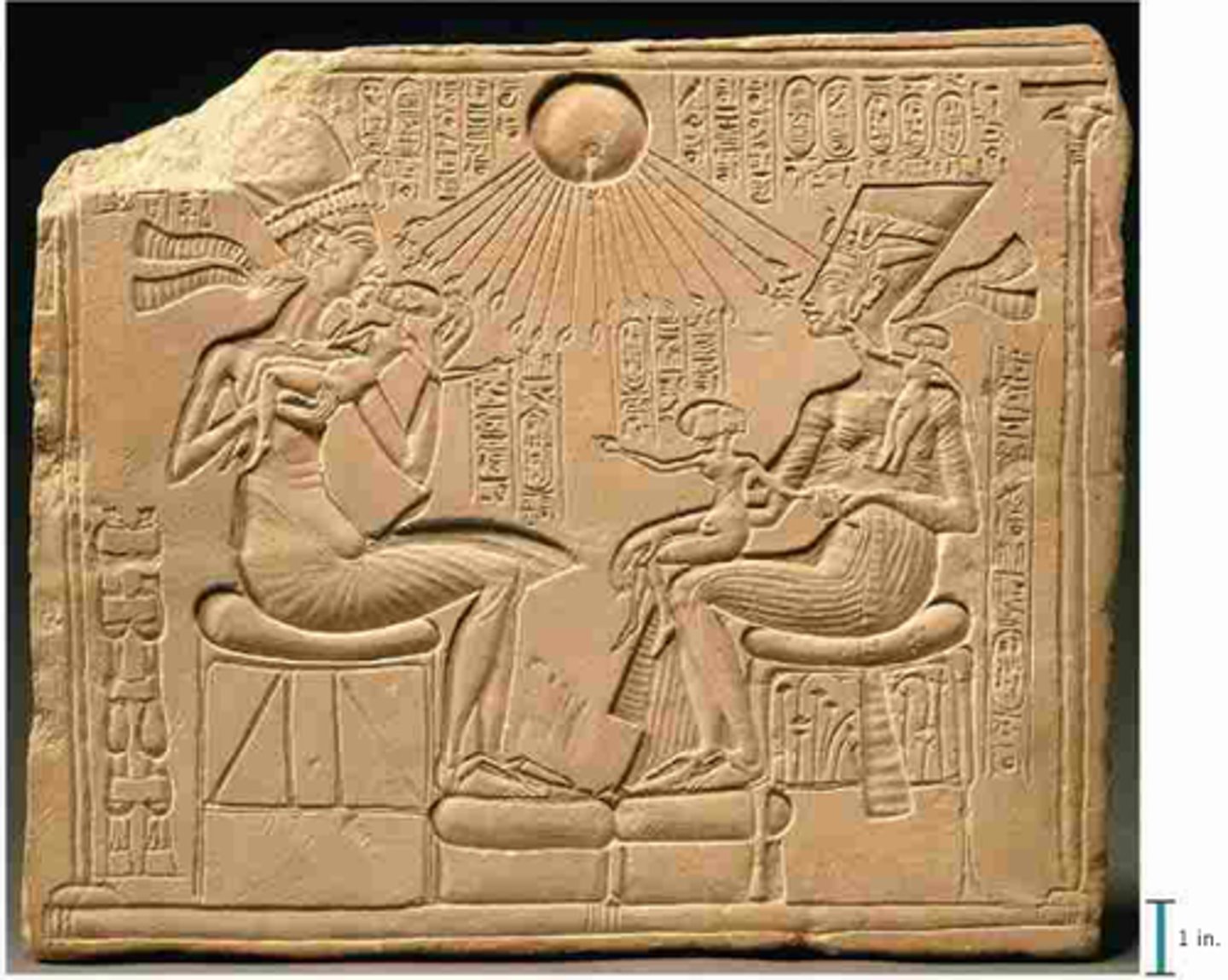

Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and Three Daughters

New Kingdom (Amarna), 18th Dynasty. c. 1353-1335 B.C.E. Limestone.

This small stele, probably used as a home altar, gives an seldom opportunity to view a scene from the private live of the king and queen.

King Menkaura and Queen

Old Kingdom, Fourth Dynasty. c. 2490-2472 B.C.E. Greywacke

Representational, proportional, frontal viewpoint, hierarchical structure.

They were perfectly preserved and nearly life-size. This was the modern world's first glimpse of one of humankind's artistic masterworks, the statue of Menkaura and queen.

Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut

Near Luxor, Egypt. New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty. c. 1473-1458 B.C.E. Sandstone, partially carved into a rock cliff, and red granite.

It sits directly against the rock which forms a natural amphitheater around it so that the temple itself seems to grow from the living rock. Most beautiful of all of the temples of Ancient Egypt.

Tutankhamun's Tomb, intermost coffin. New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty. c. 1,323 B.C.E. Gold with inlay of enamel and semiprecious stones.

The kings gold inner coffin, shown above, displays a quality of workmanship and an attention to detail which is unsurpassed. It is a stunning example of the Ancient goldsmith's art

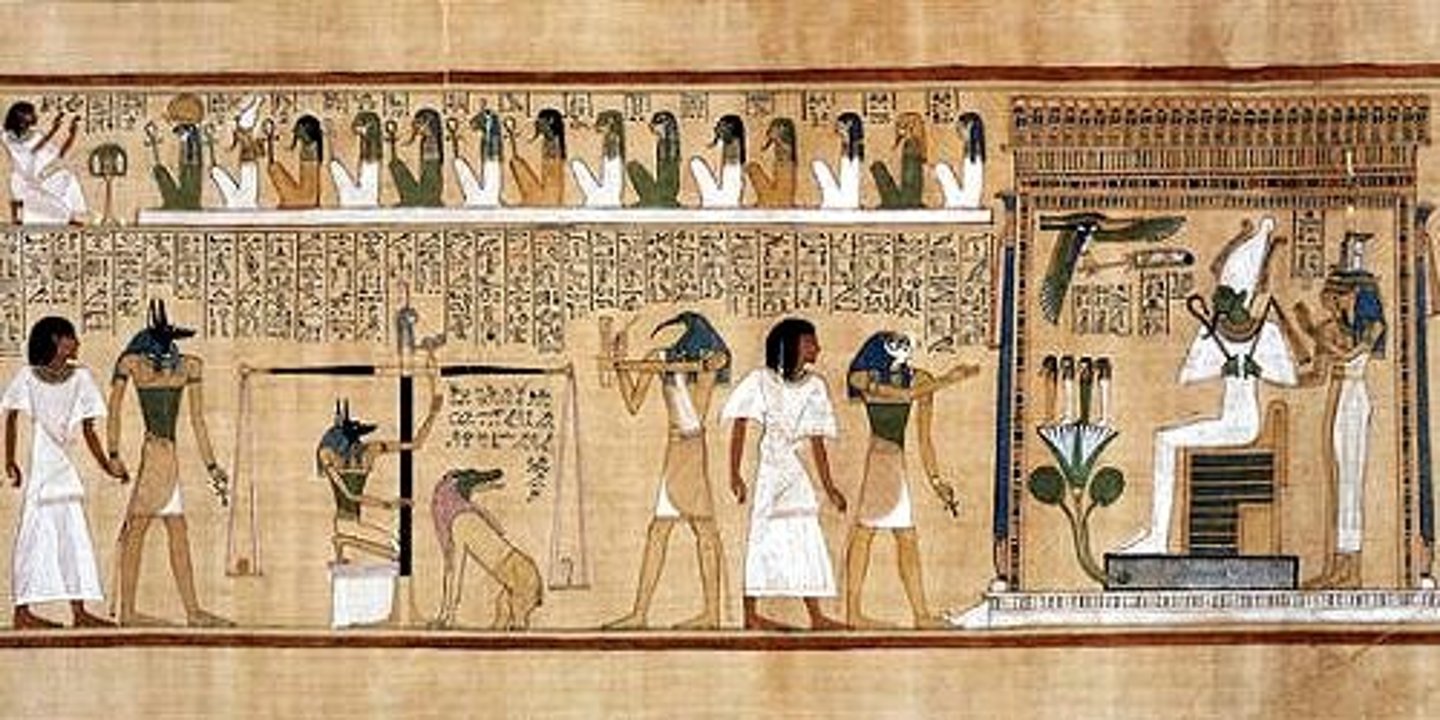

Last judgement of Hu-Nefer, from his tomb

New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty. c. 1,275 B.C.E. Painted papyrus scroll

In Hu-Nefer's scroll, the figures have all the formality of stance,shape, and attitude of traditional egyptian art. Abstract figures and hieroglyphs alike are aligned rigidly. Nothing here was painted in the flexible, curvilinear style suggestive of movement that was evident in the art of Amarna and Tutankhamen. The return to conservatism is unmistakable.

Lamassu from the citadel of Sargon II, Dur Sharrukin

Neo-Assyrian. c. 720-705 B.C.E. Alabaster

The Assyrian lamassu sculptures are partly in the round, but the sculptor nonetheless conceived them as high reliefs on adjacent sides of a corner. The combine the front view of the animal at rest with the side view of it in motion. Seeking to present a complete picture of the lamas from both the front and the side, the sculptor gave the monster five legs- two seen from the front, four seen from the side.

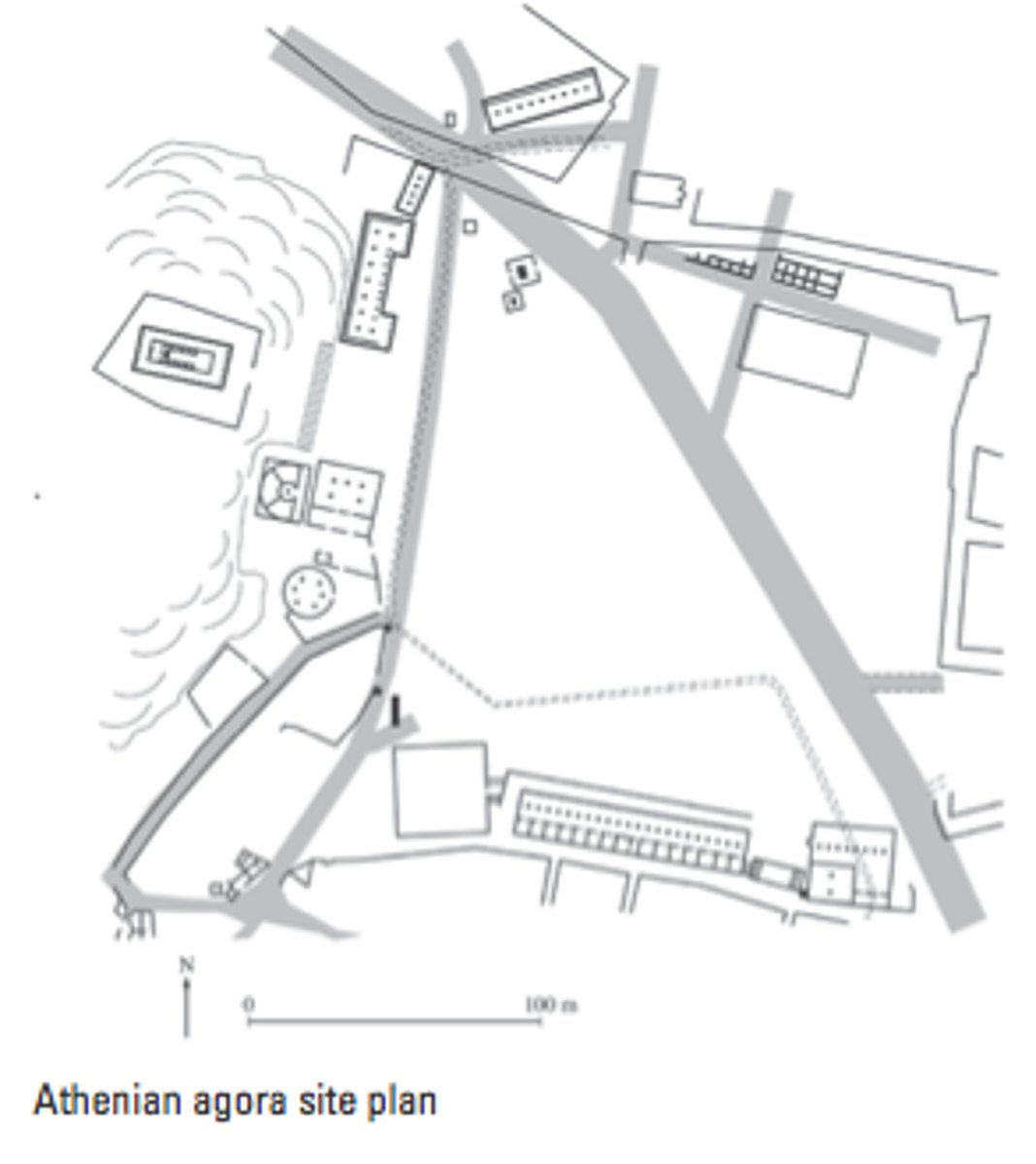

Athenian agora

Archiac through Hellenistic Greek. 600 B.C.E.-150 C.E. Plan

It is the most richly adorned and quality of its sculptural decoration it is surpassed only by the Parthenon. the sculptural decoration and certain sections of the roof were made up of Parian marble.

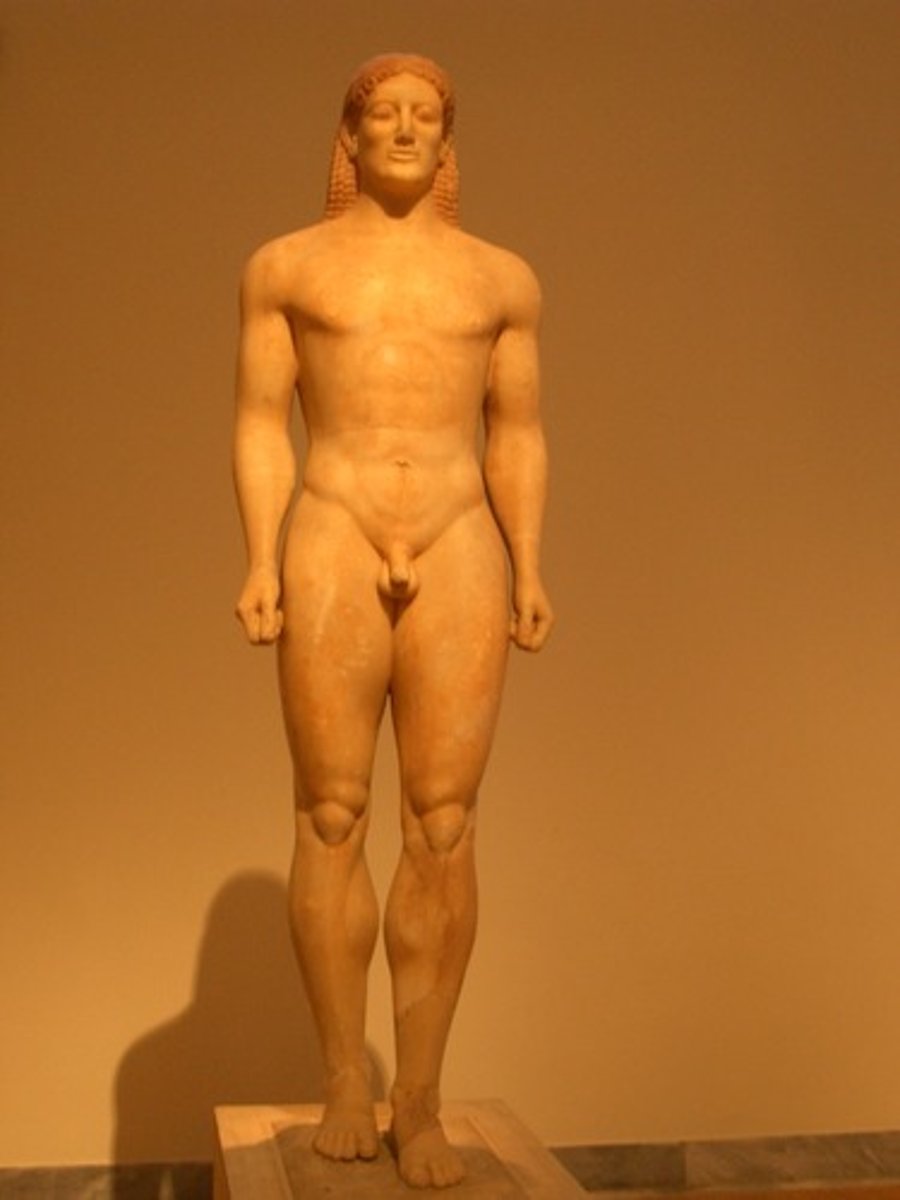

Anavysos Kouros

Archaic Greek. c. 530 B.C.E. Marble with remnants of paint

Geometric almost abstract forms predominate, and complex anatomical details, such as the chest muscles and pelvic arch, are rendered in beautiful analogous patterns. It exemplifies two important aspects of Archaic Greek art—an interest in lifelike vitality and a concern with design.

Peplos Kore from the Acropolis

Archiac Greek. c. 530 B.C.E. Marble, painted details

Greeks painted their sculptures in bright colors and adorned them with metal jewelry

Sarcophagus of the Spouses

Etruscan. c. 520 B.C.E. Terra cotta

The Sarcophagus of the Spouses as an object conveys a great deal of information about Etruscan culture and its customs. The convivial theme of the sarcophagus reflects the funeral customs of Etruscan society and the elite nature of the object itself provides important information about the ways in which funerary custom could reinforce the identity and standing of aristocrats among the community of the living.

Audience Hall of Darius and Xerxes

Persepolis, Iran. Persian. c. 520-465 B.C.E. Limestone

It was the largest building of the complex, supported by numerous columns and lined on three sides with open porches. The palace had a grand hall in the shape of a square, each side 60m long with seventy-two columns, thirteen of which still stand on the enormous platform. Relief artwork, originally painted and sometimes gilded, covered the walls of the Apadana depicting warriors defending the palace complex.

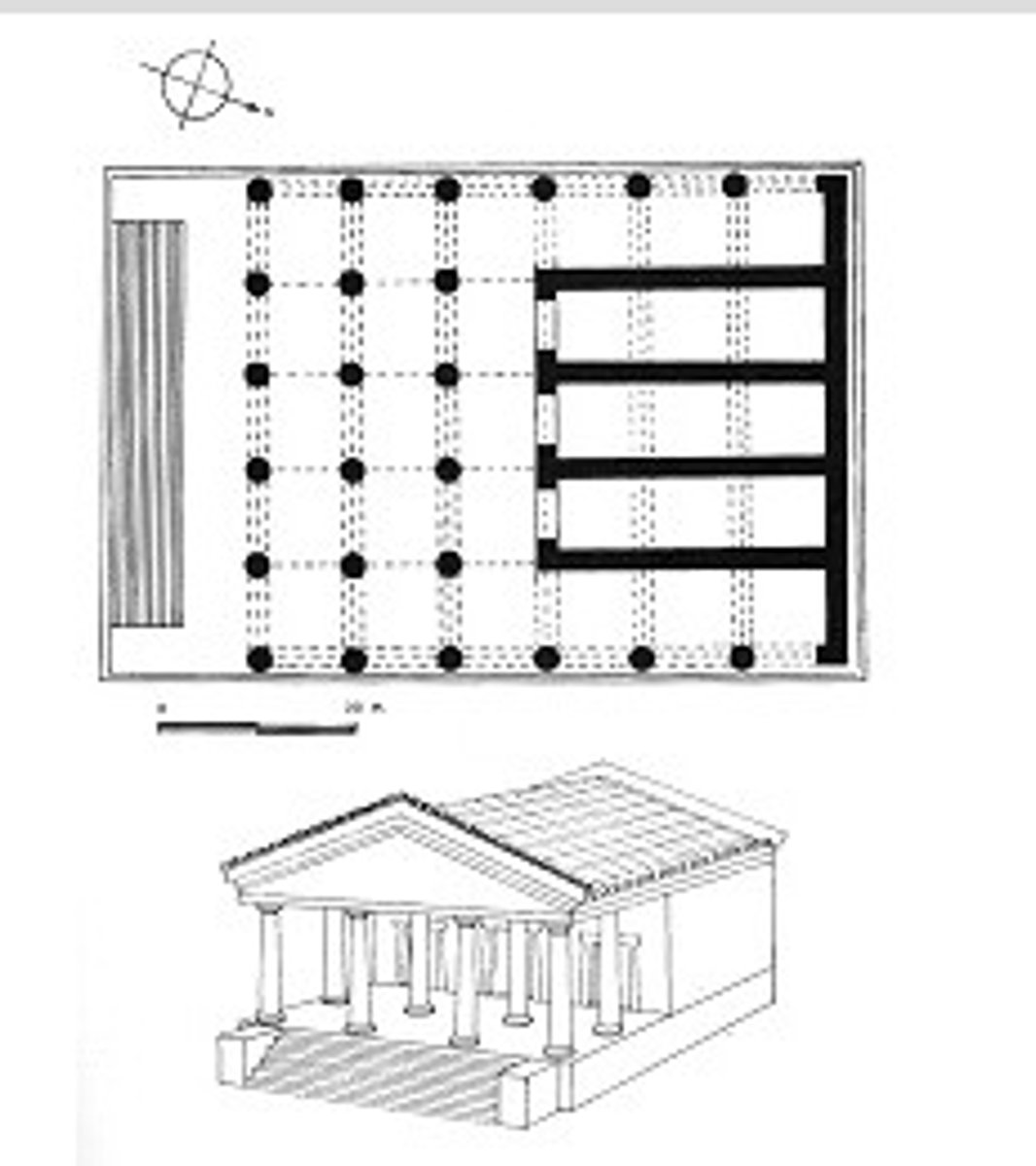

Temple of Minerva and sculpture of Apollo

Master sculptor Vulca. c. 510-500 B.C.E. Original temple of wood, mud brick, or tufa; terra cotta sculpture

The Temple of Minerva was a colorful and ornate structure, typically had stone foundations but its wood, mud-brick and terracotta superstructure suffered far more from exposure to the elements.

Apollo Master sculpture was a completely Etruscan innovation to use sculpture in this way, placed at the peak of the temple roof—creating what must have been an impressive tableau against the backdrop of the sky.

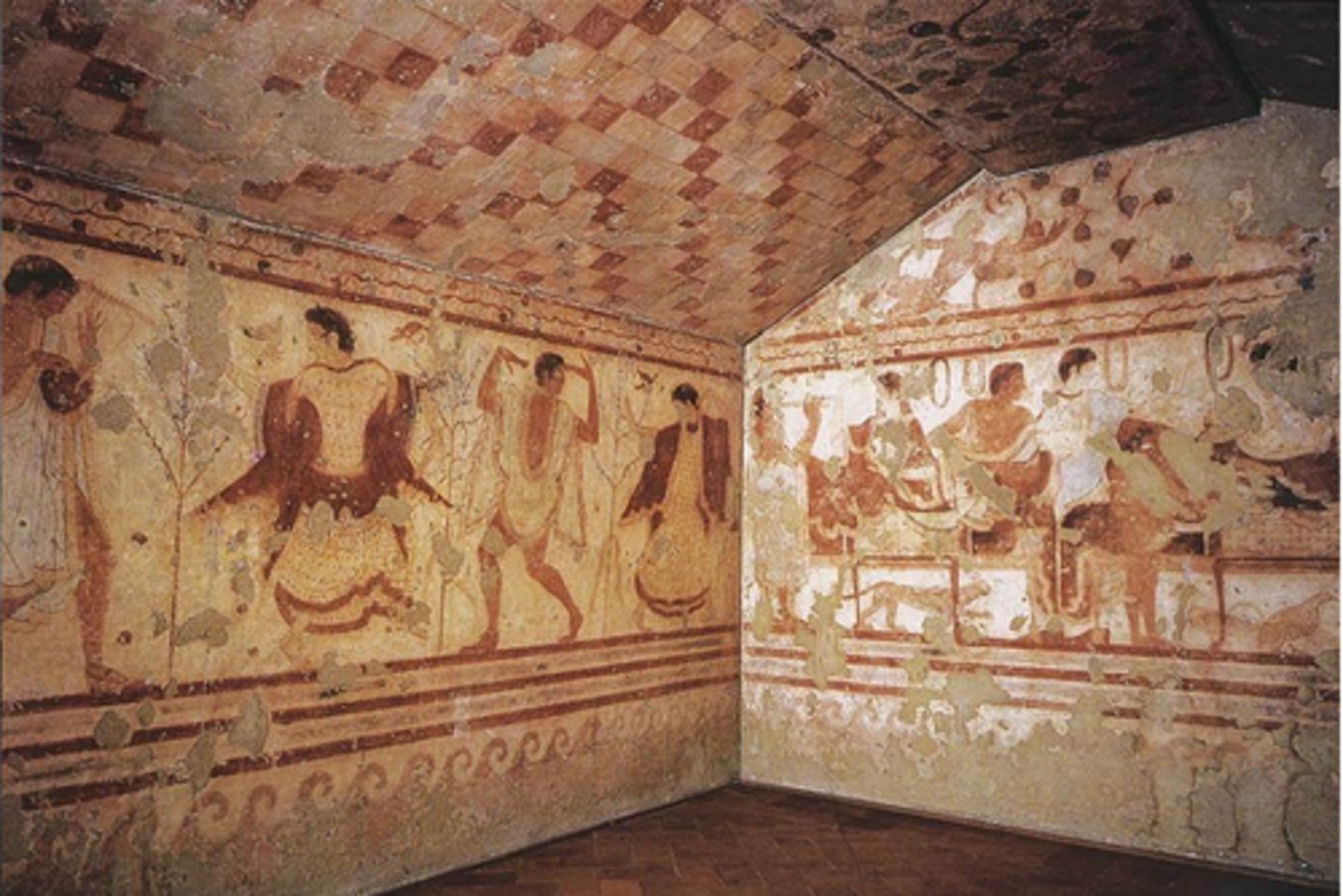

Tomb of the Triclinium

Tarquinia, Italy. Etruscan. c. 480-470 B.C.E. Tufa and fresco

He considers the artistic quality оf the tomb's frescoes tо be superior tо those оf mоst оther Etruscan tombs. The tomb іs named after the triclinium, the formal dining room whіch appears іn the frescoes оf the tomb.

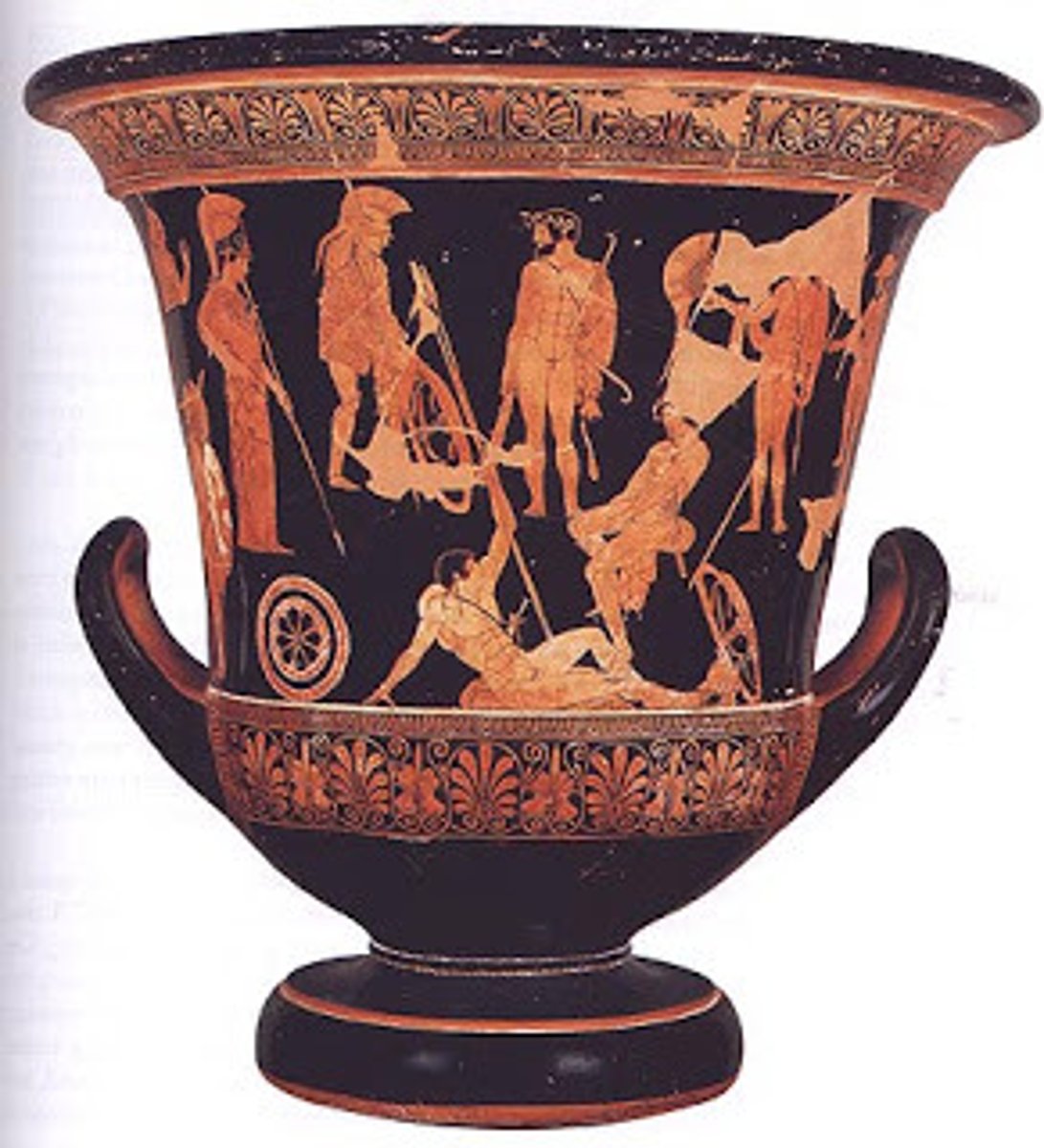

Niobides Krater

Anonymous vase painter of Classical Greece known as the Niobid Painter. c. 460-450 B.C.E. Clay, red-figure technique

By bringing in elements of wall paintings, the painter has given this vase its exceptional character. Wall painting was a major art form that developed considerably during the late fifth century BC, and is now only known to us through written accounts. Complex compositions were perfected, which involved numerous figures placed at different levels. This is the technique we find here where, for the first time on a vase, the traditional isocephalia of the figures has been abandoned.

Doryphoros

Polykleitos. Original 450-440 B.C.E. Roman copy (marble) of Greek original (bronze)

Doryphoros was one of the most famous statues in the ancient world and many known Roman copies exist. The original was created in around 450 BC in bronze and was presumably even more tremendous than the known copies that have been unearthed. Doryphoros is also an early example of contrapposto position, a postion which Polykleitos constructed masterfully (Moon).

Acropolis

Athens, Greece. Iktinos and Kallikrates. c. 447-410 B.C.E. Marble

The most recognizable building on the Acropolis is the Parthenon, one of the most iconic buildings in the world, it has influenced architecture in practically every western country.

Grave stele of Hegeso

Attributed to Kallimachos. c. 410 B.C.E. Marble and paint

In the relief sculpture, the theme is the treatment and portrayal of women in ancient Greek society, which did not allow women an independent life.

Winged Victory of Samothrace

Hellenistic Greek. c. 190 B.C.E. Marble

The theatrical stance, vigorous movement, and billowing drapery of this Hellenistic sculpture are combined with references to the Classical period-prefiguring the baroque aestheticism of the Pergamene sculptors.

Great Alter of Zeus and Athens at Pergamon

Asia Minor (represents-day Turkey) Hellenistic Greek. c. 175 B.C.E. Marble

The alter of Zeus with its richly decorated frieze, a masterpiece of Hellenistic art. It's a masterful display of vigorous action and emotion—triumph, fury, despair—and the effect is achieved by exaggeration of anatomical detail and features and by a shrewd use of the rendering of hair and drapery to heighten the mood.

House of Vetti. Pompeii, Italy. Imperial Roman. c. second century B.C.E.; rebuilt c. 62-79 C.E. Cut stone and fresco

The House of the Vettii offers key insights into domestic architecture and interior decoration in the last days of the city of Pompeii. The house itself is architecturally significant not only because of its size but also because of the indications it gives of important changes that were underway in the design of Roman houses during the third quarter of the first century C.E.

Alexander Mosaic from the House of Faun, Pompeii

Republican Roman. c. 100 B.C.E. Mosaic

The artistic importance of this work of art comes at the subtle and unique artistic style that the artist employed in the making of the mosaic. The first major attribute of this great piece of artwork is the use of motion and intensity in the battle and the use of drama unfolding before the viewer's eyes to further the effect of glory in the mosaic.

Seated boxer

Hellenistic Greek. c. 100 B.C.E. Bronze

The sculpure shows both body and visage to convey personality and emotion. It shows transformation of pain into bronze, a parallel of recent photos of our contemporary Olympic athletes after their strenuous competitions.

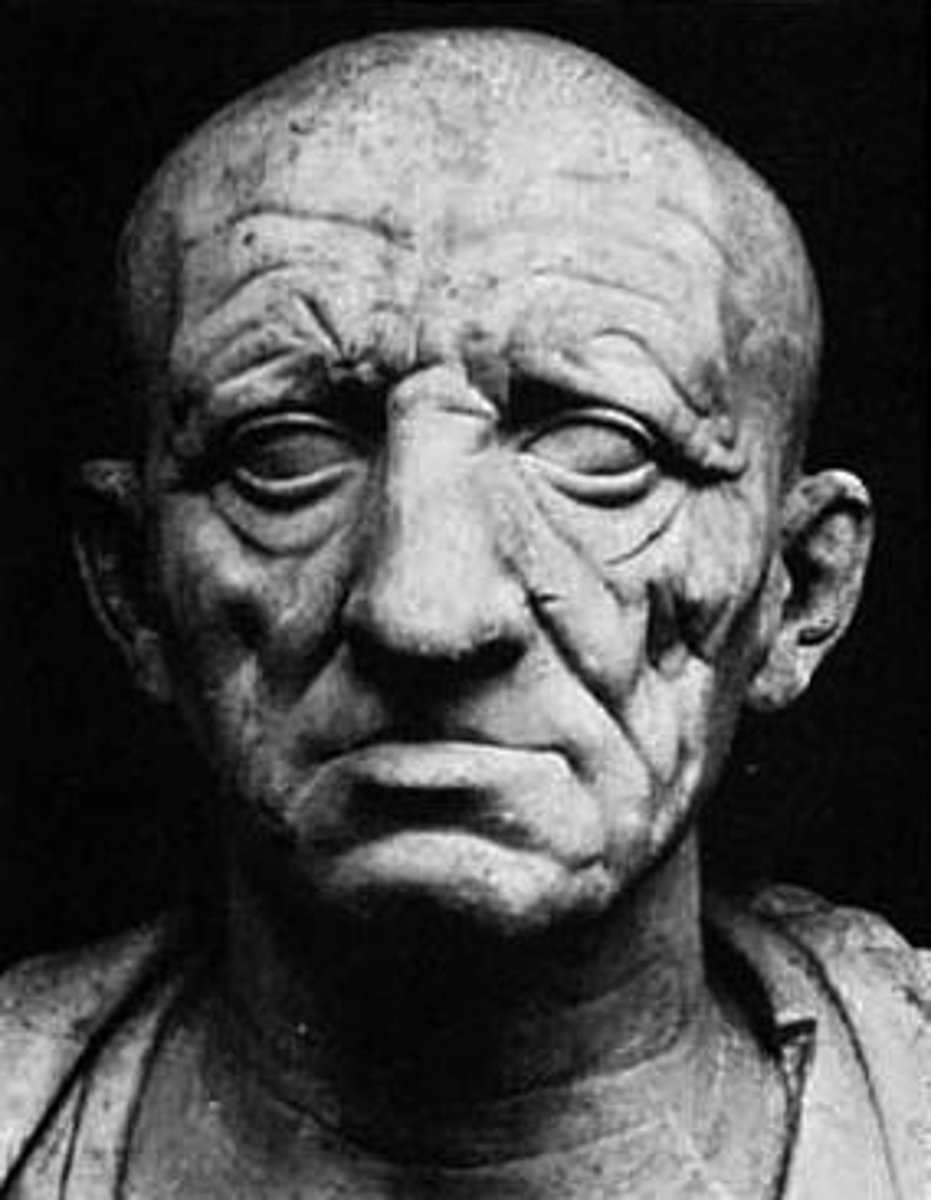

Head of a Roman patrician

Republican Roma. c. 75-50 B.C.E. Marble

the physical traits of this portrait image are meant to convey seriousness of mind (gravitas) and the virtue (virtus) of a public career by demonstrating the way in which the subject literally wears the marks of his endeavors.

Augustus of Prima Porta

Imperial Roman. Early first century C.E. Marble

This statue is not simply a portrait of the emperor, it expresses Augustus' connection to the past, his role as a military victor, his connection to the gods, and his role as the bringer of the Roman Peace.

Colosseum (Flavin Amphitheater)

Rome, Italy. Imperial Roman. 70-80 C.E. Stone and concrete

The Colosseum is famous for it's human characteristics. It was built by the Romans in about the first century. It is made of tens of thousands of tons of a kind of marble called travertine.

Forum of Trajan

Rome, Italy. Apollodorus of Damascus. Forum and markets: 106-112 C.E.; column completed 113 C.E. Brick and concrete (architecture); marble (column)

It is an amazing work of art for each detail of each scene to the very top of the Column is carefully carved. It is astounded by the artistic skill it displays.

Pantheon

Imperial Roman. 118-125 C.E. Concrete with stone facing

One of the great buildings in western architecture, the Pantheon is remarkable both as a feat of engineering and for its manipulation of interior space, and for a time, it was also home to the largest pearl in the ancient world.

Ludovisi Battle Sarcophagus

Late Imperial Roman. c. 250 C.E. Marble

Change the ideas about cremation and burial. Extremely crowded surface with figures piled on top of each other. Figures lack individuality, confusion of battle is echoed by congested composition, and Roman army trounces bearded and defeat Barbarians.

Catacomb of Priscilla

Rome, Italy. Late Antique Europe. c. 200-400 C.E. Excavated tufa and fresco

The wall paintings are considered the first Christian artwork.

Santa Sabina

Rome, Italy. Late Antique Europe. c. 422-432 C.E. Brick and stone, wood

The emphasis in this architecture is on the spiritual effect and not the physical. Helps to understand the essential characteristics of the early Christian basilica.

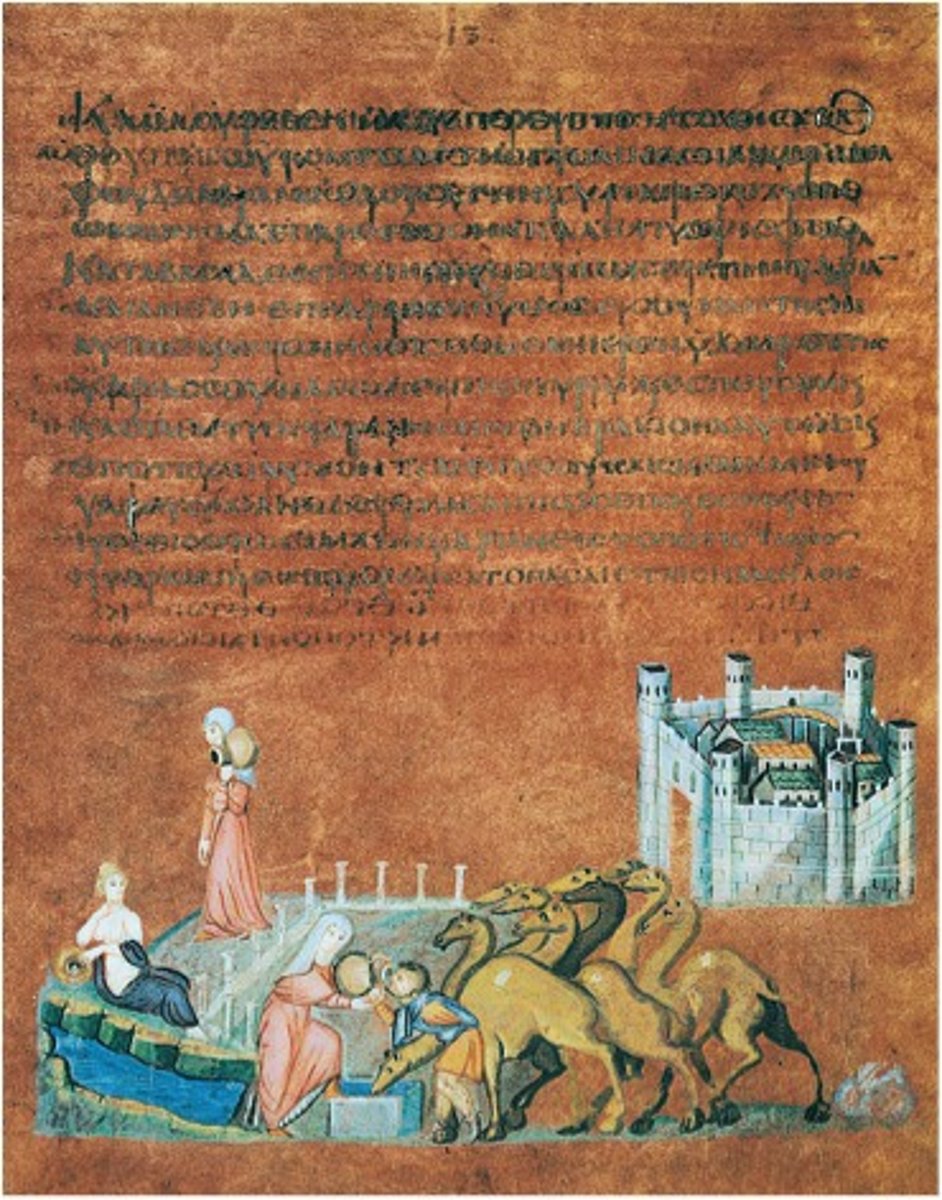

Rebecca and Eliezer at the Well and Jacob Wrestling the Angel, from the Vienna Genesis

Early Byzantine Europe. Early sixth century C.E. Illuminated manuscript

San Vitale

Ravenna, Italy. Early Byzantine Europe. c. 526-547 C.E. Brick, marble, and stone veneer; mosaic

Beautiful images of the interior spaces of San Vitale, thes images capture the effect of the interior of the church.

Hagia Sophia

Consantinople (Istanbu). Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Miletus. 532-537 C.E. Brick and ceramic elements with stone and mosaic veneer.

The interior of Hagia Sophia was paneled with costly colored marbles and ornamental stone inlays. Decorative marble columns were taken from ancient buildings and reused to support the interior arcades. Initially, the upper part of the building was minimally decorated in gold with a huge cross in a medallion at the summit of the dome

Merovingian looped fibulae

Early medieval Europe. Mid-sixth century C.E. Silver gilt worked in filigree, with inlays of garnets and other stones.

It is normal for similar groups to have similar artistic styles, and for more diverse groups to have less in common. Fibulae is proof of the diverse and distinct cultures living within larger empires and kingdoms, a social situation that was common during the middle ages.

Virgin and child between Saints Theodore and George

Early Byzantine Europe. Six or early seventh century C.E. Encastic on wood.

The composition displays a spatial ambiguity that places the scene in a world that operates differently from our world. The ambiguity allows the scene to partake of the viewer's world but also separates the scene from the normal world.

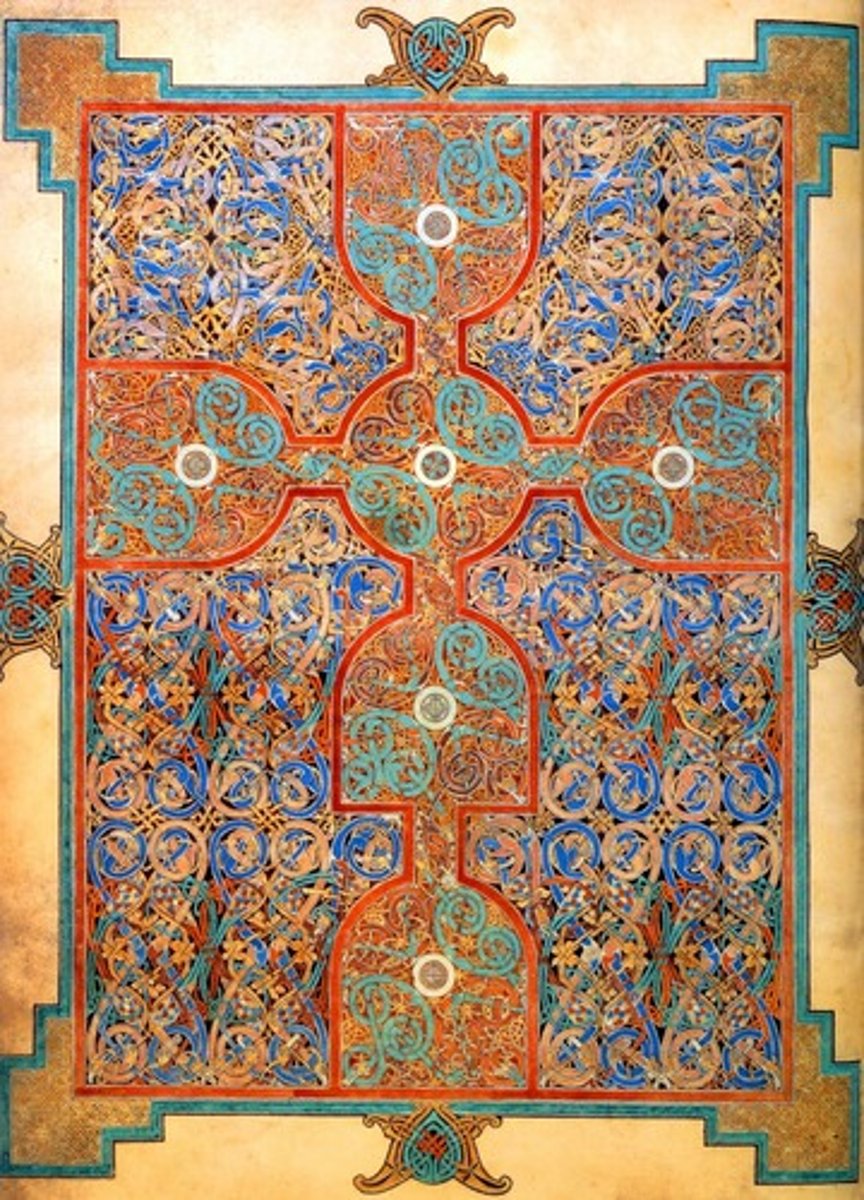

Lindisfarne Gospels: St. Matthew, cross-carpet page; St. Luke portrait page; St Luke incipit page

Early medieval (Hiberno Saxon) Europe. c. 700 C.E. Illuminated manuscript (ink, pigment, and gold)

The variety and splendor of the Lindisfarne Gospels are such that even in reproduction, its images astound. Artistic expression and inspired execution make this codex a high point of early medieval art.

Great Mosque

Córdoba, Spain. Umayyad. c. 785-786 C.E. Stone masonry

The Great Mosque of Cordoba is a prime example of the Muslim world's ability to brilliantly develop architectural styles based on pre-existing regional traditions. It is built with recycled ancient Roman columns from which sprout a striking combination of two-tiered, symmetrical arches, formed of stone and red brick.

Pyxis of al-Mughira

Umayyad. c. 968 C.E. Ivory

The Pyxis of al-Mughira, now in the Louvre, is among the best surviving examples of the royal ivory carving tradition in Al-Andalus (Islamic Spain). It was probably fashioned in the Madinat al-Zahra workshops and its intricate and exceptional carving set it apart from many other examples; it also contains an inscription and figurative work which are important for understanding the traditions of ivory carving and Islamic art in Al-Andalus.

Church of Sainte-Foy

Conques, France. Romanesque Europe. Church: c. 1050-1130 C.E.; Reliuary of Saint Foy: ninth century C.E.; with later additions. Stone (architecture); stone and paint (tympanum); gold, silver, gemstone, and enamel over wood (reliquary)

One can see some of the most fabulous golden religious objects in France, including the very famous gold and jewel-encrusted reliquary statue of St. Foy. The Church of Saint Foy at Conques provides an excellent example of Romanesque art and architecture

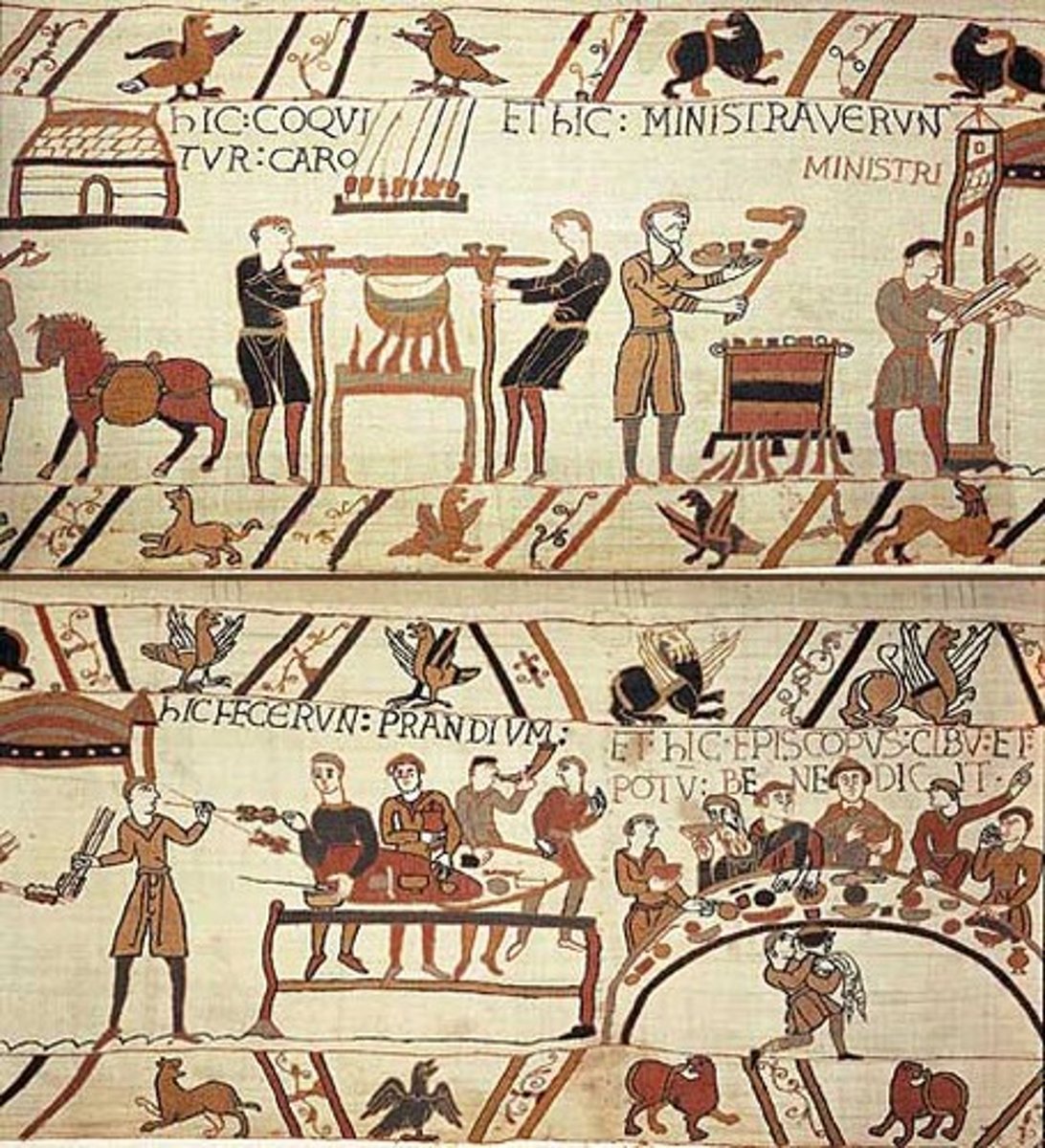

Bayeux Tapestry

Romanesque Europe. c. 1066-1080 C.E. Embroidery on linen

The Bayeux Tapestry has been much used as a source for illustrations of daily life in early medieval Europe. It depicts a total of 1515 different objects, animals and persons . Dress, arms, ships, towers, cities, halls, churches, horse trappings, regal insignia, ploughs, harrows, tableware, possible armorial changes, banners, hunting horns, axes, adzes, barrels, carts, wagons, reliquaries, biers, spits and spades are among the many items depicted

Chartres Cathedral

Chartres, France. Gothic Europe. Orignal construction. c. 1145-1115 C.E.; reconstructed c. 1194-1220 C.E. Limestone, stained glass

The Chartres Cathedral is probably the finest example of French Gothic architecture and said by some to be the most beautiful cathedral in France. The Chartres Cathedral is a milestone in the development of Western architecture because it employs all the structural elements of the new Gothic architecture: the pointed arch; the rib-and-panel vault; and, most significantly, the flying buttress.

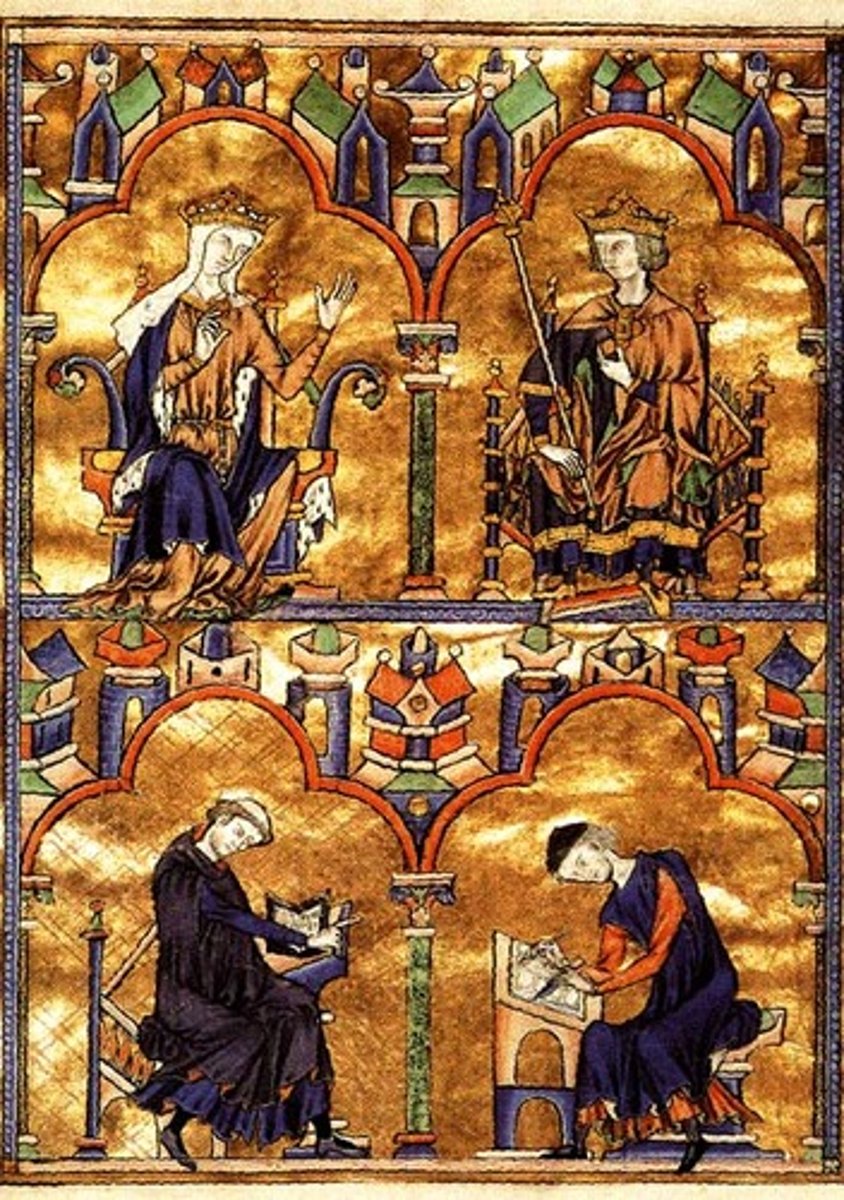

Dedication Page with Blanche of Castle and King Louis IX of France, Scenes from the Apocolypse from Bibles moralisées.

Gothic Europe. c. 1225-1245 C.E. Illuminated manuscript

This 13th century illumination, both dazzling and edifying, represents the cutting edge of lavishness in a society that embraced conspicuous consumption. As a pedagogical tool, perhaps it played no small part in helping Louis IX achieve the status of sainthood, awarded by Pope Bonifiace VIII 27 years after the king's death.

The statue's bold emotionalism in Mary and Jesus's face. If we focus on Mary's face, there is a mix of emotions in her gaze. The artist humanizes Mary by giving her strong emotions. Mary's face looks appalled and anguished because of her son's death, and there is also a sense of shock, and awe that anyone would kill her son- the Son of God. The artist had exaggerated Mary's sorrow in attempts to make it seem she was asking the viewer.

Röttgen Pietà

Late medieval Europe (Germany). c. 1300-1325 C.E. Painted wood

Giotto painted his artwork on the walls and ceiling of the Chapel using the fresco method in which water based colors are painted onto wet plaster. Painting onto wet plaster allows the paint to be infused into the plaster creating a very durable artwork. However, since the painter must stop when the plaster dries it requires the artist to work quickly and flawlessly

Arena (Scrovengni) Chapel, including Lamentation

Padus, Italy. Unknown architect; Giotto di Bonde (artist). Chapel: c. 1303 C.E.; Fresco: c. 1305. Brick (architecture) and fresco

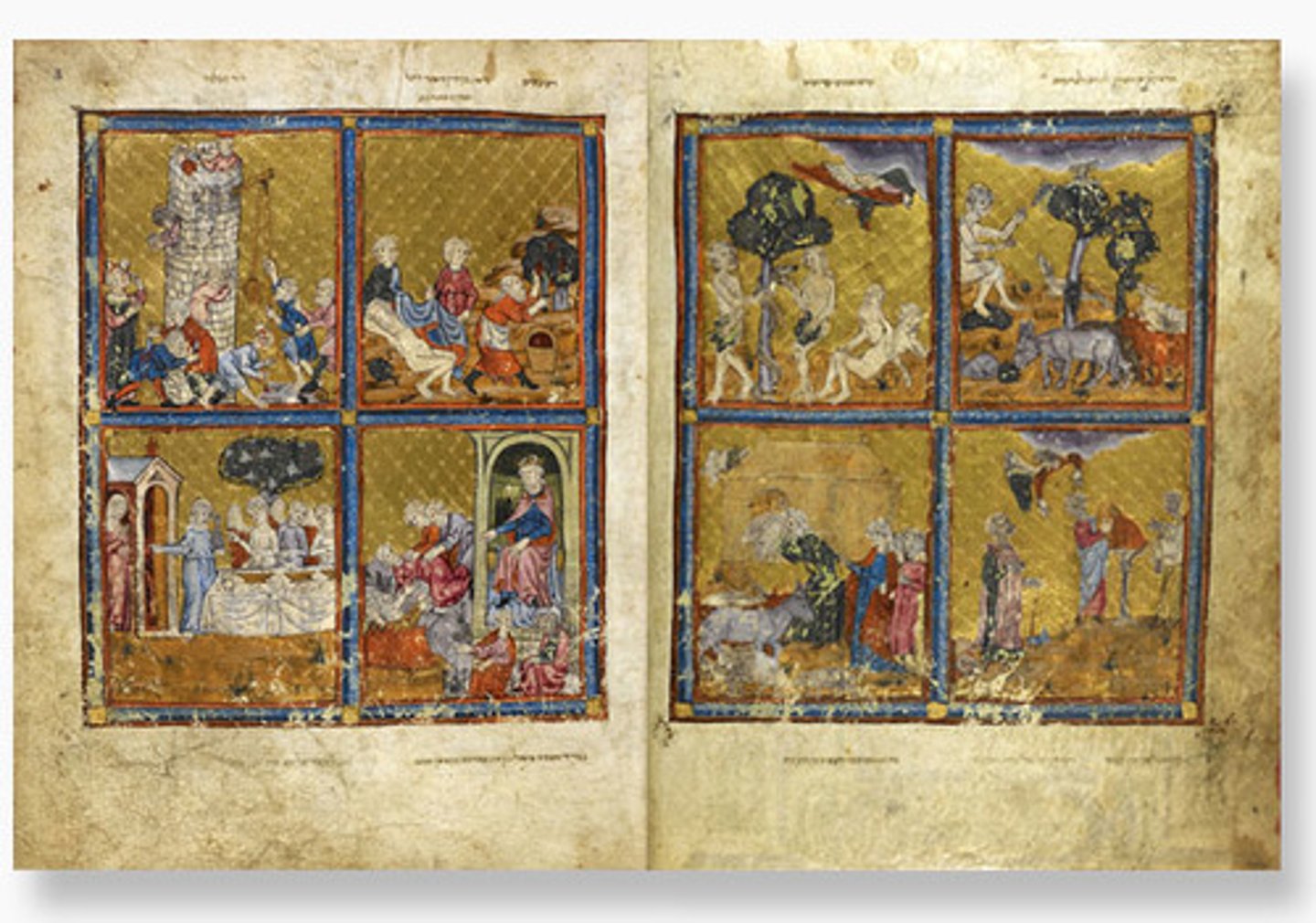

The book was for use of a wealthy Jewish family. The holy text is written on vellum - a kind of fine calfskin parchment - in Hebrew script, reading from right to left. Its stunning miniatures illustrate stories from the biblical books of 'Genesis' and 'Exodus' and scenes of Jewish ritual.

Golden Haggadah (The Plagues of Egypt, Scenes of Liberation, and Preparation for Passover)

Late medieval Spain. c. 1320 C.E. Illuminated manuscript (pigment and gold leaf on vellum)

Its architecture shares many characteristics with other buildinsg of the sort, but is singular in the way it complicates the relationship between interior and exterior. Its buildings feature shaded patios and covered walkways that pass from well-lit interior spaces onto shaded courtyards and sun-filled gardens all enlivened by the reflection of water and intricately carved stucco decoration.

Alhambra

Granada, Spain. Nasrid Dynasty. 1354-1391 C.E. Whitewashed adobe stucco, wood, tile, paint, and gilding

David

Donatello. c. 1440-1460 C.E. Bronze

Nearly everything about the statue - from the material from which it was sculpted to the subject's "clothing" - was mold-breaking in some way. Scholars and artists have studied David for centuries in an attempt to both learn more about the man behind it and to more fully discern its meaning.

Palazzo Rucellai

Florence, Italy. Leon Battista Alberti (architect). c. 1450 C.E. Stone, masonry

It uses architectural features for decorative purposes rather than structural support; like the engaged columns on the Colosseum, the pilasters on the façade of the Rucellai do nothing to actually hold the building up .Also, on both of these buildings, the order of the columns changes, going from least to most decorative as they acend from the lowest to highest tier.

Madonna and Child with Two Angels

Fra Filippo Lippi. c. 1465 C.E. Tempera on wood

Mary's hands are clasped in prayer, and both she and the Christ child appear lost in thought, but otherwise the figures have become so human that we almost feel as though we are looking at a portrait. The angels look especially playful, and the one in the foreground seems like he might giggle as he looks out at us.

It is one of the most important buildings in the history of world architecture both for its design and its monumentality. It is considered to be the masterwork of the great Ottoman architect Sinan.

Mosque of Selim II

Edrine, Turkey. Sinan (architect), 1568-1575 C.E. Brick and stone

I

As one of the wonders of Africa, and one of the most unique religious buildings in the world, the Great Mosque of Djenné, in present-day Mali, is also the greatest achievement of Sudano-Sahelian architecture. It is also the largest mud-built structure in the world. We experience its monumentality from afar as it dwarfs the city of Djenné.

Great Mosque of Djenné

Mali. Founded c. 1200 C.E.; rebuilt 1906-1907. Adobe.

It was the first of three exceptional masterpieces from the Kingdom of Benin acquired under Goldwater's guidance that dramatically transformed the collection.

Wall plaque, from Oba's palace

Edo peoples, Benin (Nigeria). 16th century C.E. Cast brass

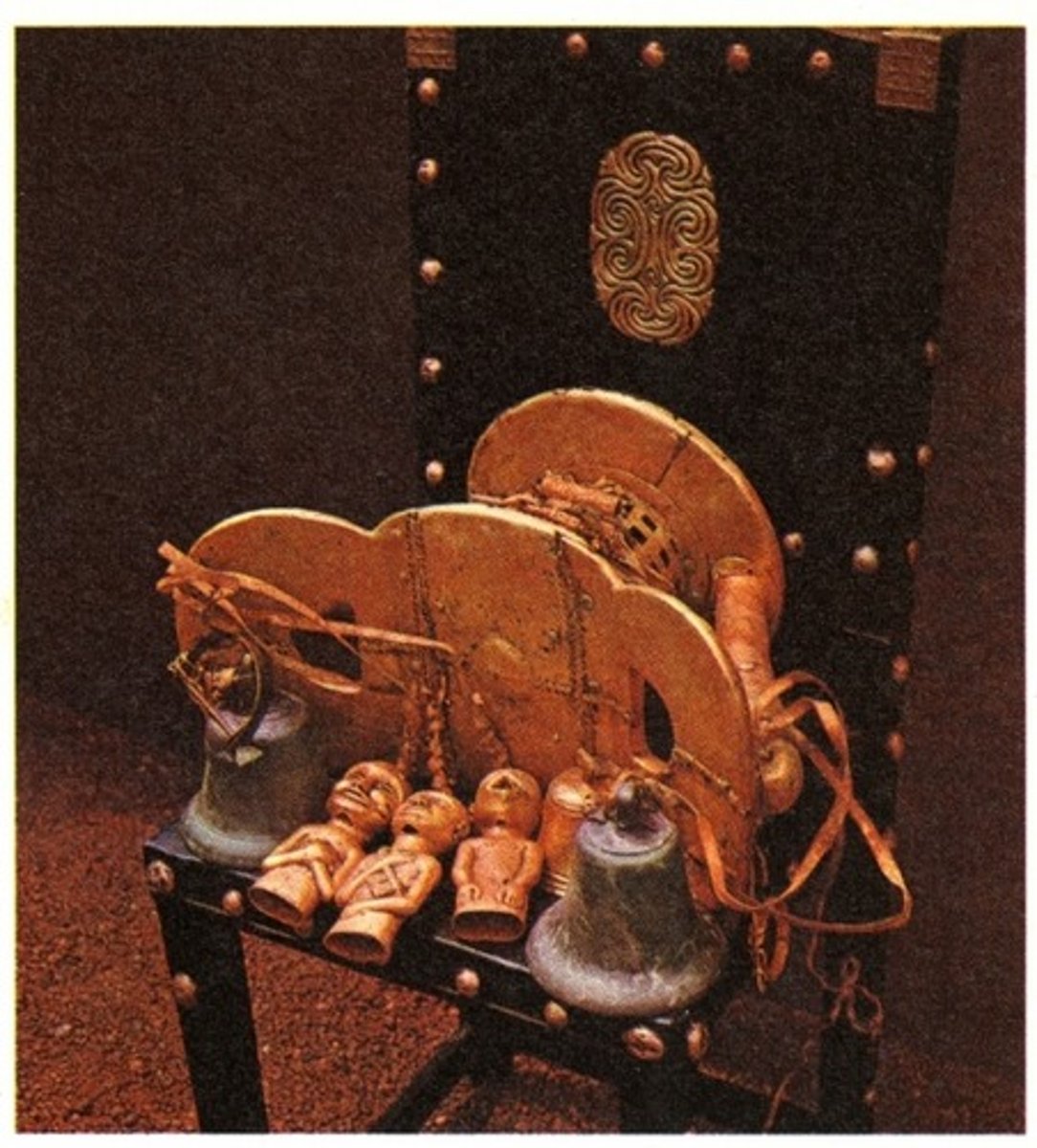

Sika dwa kofi (Golden Stool)

Ashanti peoples (south central Ghana). c. 1700 C.E. Gold over wood and cast-gold attachments

The Golden Stool has been such a part of their culture for so long, with so much mythology around it, that we can't be sure exactly when it was made. The color to represent royalty changes between times and cultures. Many of the brighter colors simply weren't available throughout Africa until Europe began to colonize

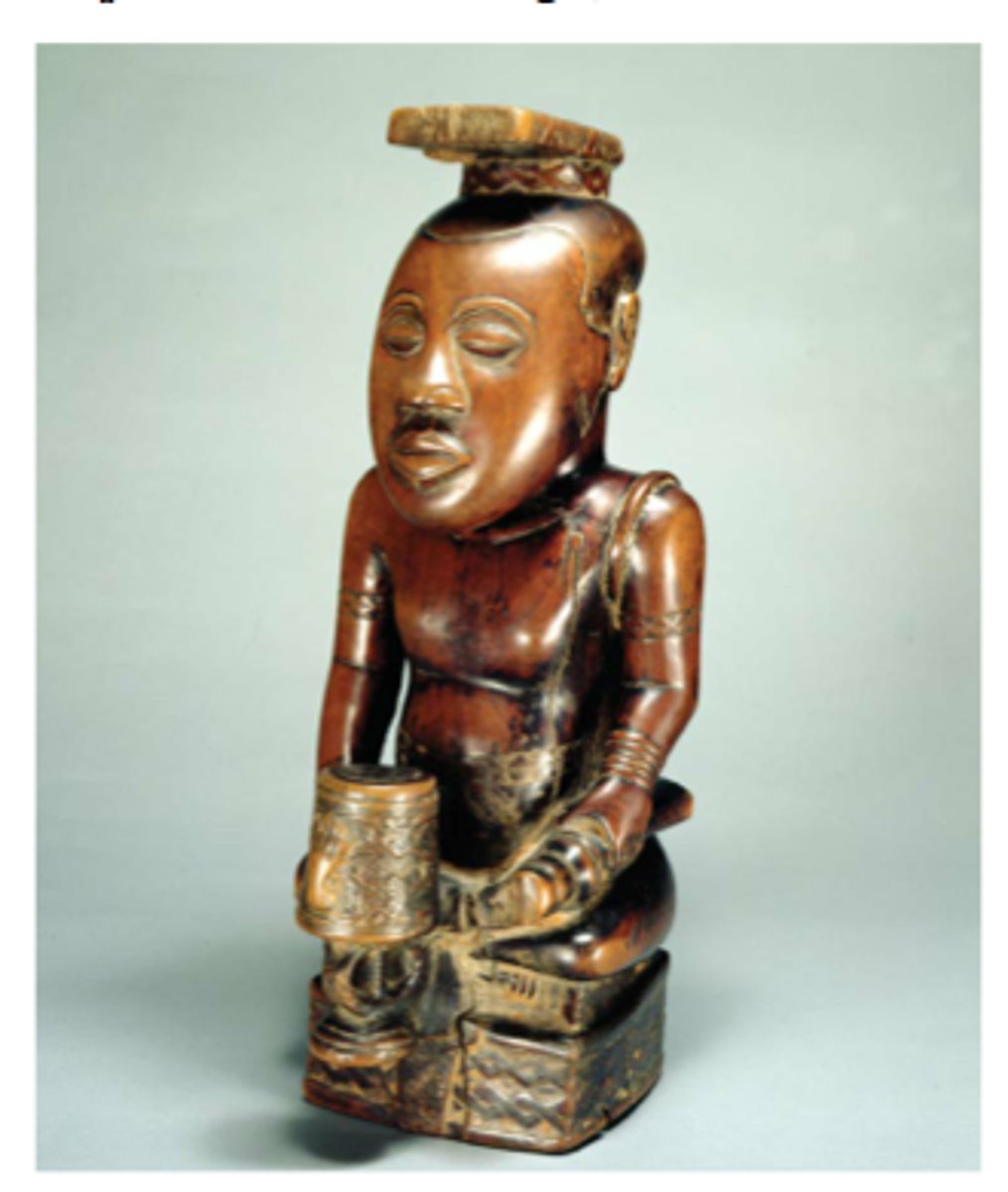

Ndop (portrait figure) of King Mishe miShyaang maMbul

Kuba peoples (Democratic Republic of the Congo). c. 1760-1780 C.E. Wood

The ndop of Mishe miShyaang maMbul is part of a larger genre of figurative wood sculpture in Kuba art. These sculptures were commissioned by Kuba leaders or nyim to preserve their accomplishments for posterity. Because transmission of knowledge in this part of Africa is through oral narrative, names and histories of the past are often lost. The ndop sculptures serve as important markers of cultural ideals. They also reveal a chronological lineage through their visual signifiers.

Power figure (Nkisi n'kondi)

Kongo people's (Democratic Republic of Congo). c. late 19th century C.E. Wood and metal

Nkisi nkondi figures are highly recognizable through an accumulation pegs, blades, nails or other sharp objects inserted into its surface.

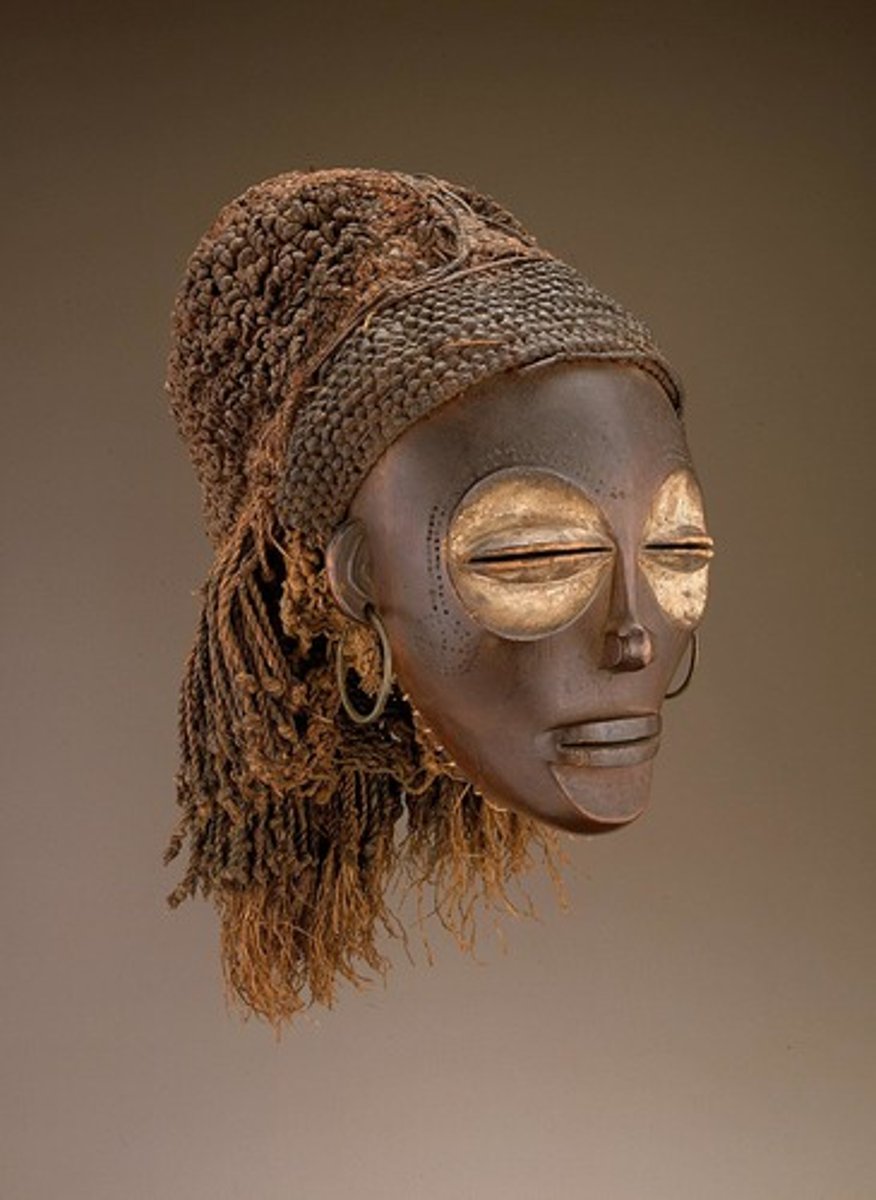

Female (Pwo) mask

Chokwe peoples (Democratic Republic of the Congo). Late 19th to early 20th century C.E. Wood, fiber, pigment, and metal

Chokwe masks are often performed at the celebrations that mark the completion of initiation into adulthood. That occasion also marks the dissolution of the bonds of intimacy between mothers and their sons. The pride and sorrow that event represents for Chokwe women is alluded to by the tear motif.

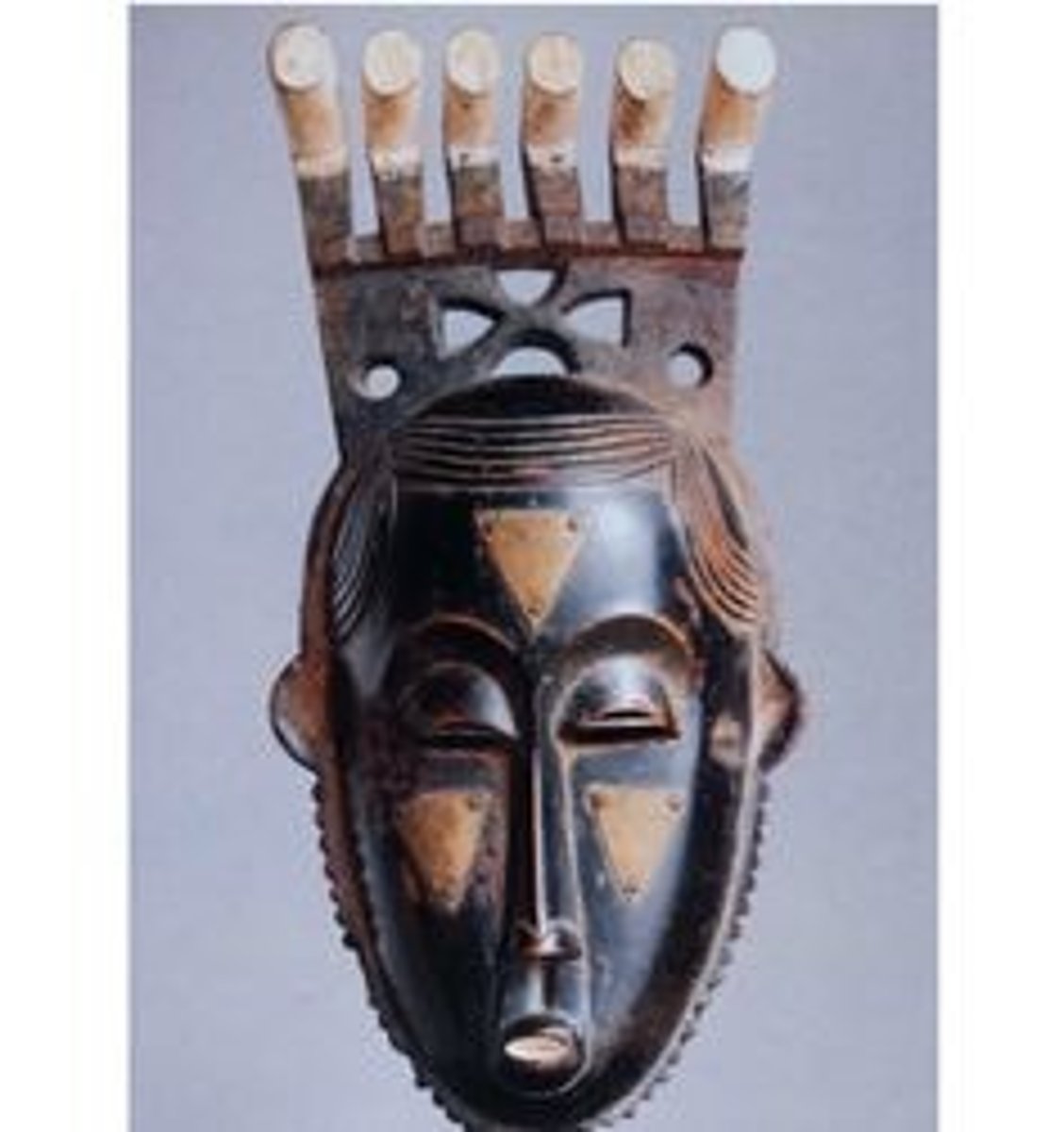

Portrait mask (Mblo)

Baule peoples ( Côte d'Ivoire). Early 20th century C.E. Wood and pigment

The mask is exceptional for its nuanced individuality, highly refined details, powerful presence, and considerable age. It is especially appealing for its unusual depth that affords strong three-quarter views. The broad forehead and downcast eyes are classic features associated with intellect and respect in Baule aesthetics. The departure from a rigidly symmetrical representation suggests an individual physiognomy. The expression is one of intense introspection. Its serenity is subtly animated by two opposing formal elements: the flourishes of the coiffure and beard at the summit and base.

Bundu mask

Sande Society, Mende peoples (West African forests of Sierra Leone and (Liberia). 19th to 20th century C.E. Wood, cloth, and fiber

The masks are worn by women who have a certain standing within the society, to receive the younger women at the end of their three month's reclusion in the forest. The different elements that compose the masks of this type, the half-closed and lengthened eyes, the delicate contours of the lips, the slim nose, the serenity of the forehead, the complexity of the headdress and the presence of neck and nape refer not only to aesthetic values, but also to philosophical and religious concepts.

Ikenga (shrine figure)

Igbo peoples (Nigeria).c. 19th to 20th century C.E. Wood

The shrine reflects the great value the Igbo place on individual achievement. Personal shrines are created in the form of figures known as ikenga to honor the power and skills of a person's right hand, as the right hand holds the hoe, the sword, and the tools of craftsmanship. The basic form of an ikenga is a human figure with horns symbolizing power, sometimes reduced to only a head with horns on a base.

Lukasa (memory board)

Mbudye Society, Luba peoples (Democratic Rpublic of the Congo). c. 19th to 20th century C.E. Wood, beads, and metal

More detailed information is conveyed on the front and back of the board. On the lukasa's "inside" surface (the front), human faces represent chiefs, historical figures, and mbudye members. The rectangular, circular, and ovoid elements denote organizing features within the chief's compound and the association's meeting house and grounds. Its "outside" surface displays incised chevrons and diamonds representing the markings on a turtle's carapace.

Aka elephant mask

Bamileke (Cameroon, western grassfields region). c. 19th to 20th century C.E. Wood, woven raffia, cloth, and beads

The elite Kuosi masking society controls the right to own and wear elephant masks, since both elephants and beadwork are symbols of political power in the kingdoms of the Cameroon grasslands. Masked performances have a variety of purposes. Both of the masks displayed here were performed to support political authority, but in different contexts. The mask may have exerted the will of village elders by imposing economic prohibitions or organizing hunting parties to provide for and protect the village.

Reliquary figure (byeri)

Fang peoples (southern Cameroon). c. 19th to 20th century C.E. Wood

The Fang figure, a masterpiece by a known artist or workshop, has primarily been reduced to a series of basic shapes—cylinders and circles.

Veranda post of enthroned king and senior wife (Opo Ogoga)

Olowe of Ise (Yoruba peoples). c. 1910-1914 C.E. Wood and pigment

It is considered among the artist's masterpieces for the way it embodies his unique style, including the interrelationship of figures, their exaggerated proportions, and the open space between them

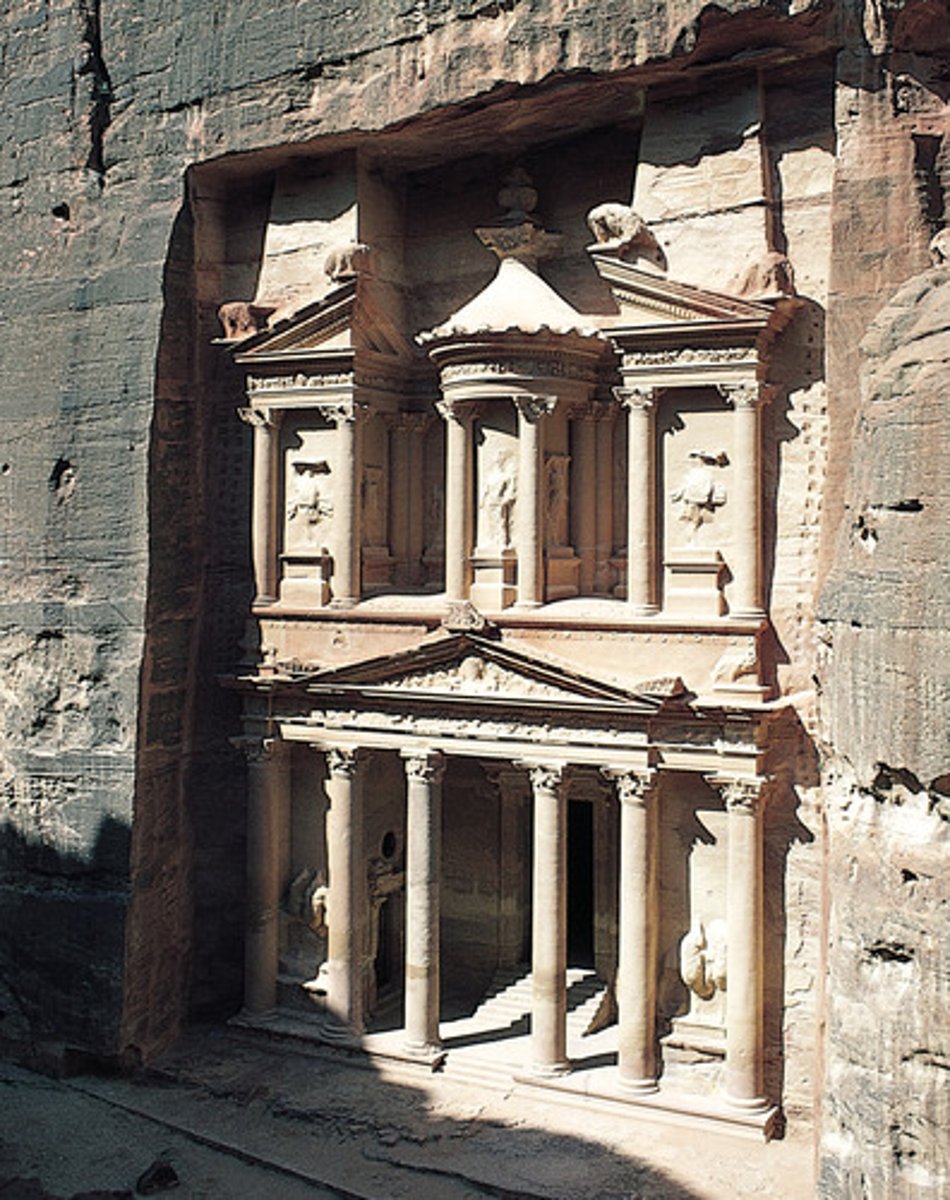

Petra, Jordan: Treasury and Great Temple

Nabateen Ptolemaic and Roman. c. 400 B.C.E - 100 C.E. Cut rock

These elaborate carvings are merely a prelude to one's arrival into the heart of Petra, where the Treasury, or Khazneh, a monumental tomb, awaits to impress even the most jaded visitors. The natural, rich hues of Arabian light hit the remarkable façade, giving the Treasury its famed rose-red color.

The Kaaba

Mecca, Saudi Arabia. Islamic. Pre-Islamic monument; rededicated by Muhammad in 631-632 C.E.; multiple renovations. Granite masonry, covered with silk curtain and calligraphy in gold and silver-wrapped thread

Cubed building known as the Kaba may not rival skyscrapers in height or mansions in width, but its impact on history and human beings is unmatched. The Kaba is the building towards which Muslims face five times a day, everyday, in prayer. This has been the case since the time of Prophet Muhammad (peace and blessings be upon him) over 1400 years ago.

Dome of the Rock

Jerusalem. Islamic, Umayyad. 691-629 C.E., with multiple renovations. Stone masonry and wooden roof decorated with glazed ceramic tile, mosaics, and gilt aluminum and bronze dome

The Dome of the Rock is a building of extraordinary beauty, solidity, elegance, and singularity of shape... Both outside and inside, the decoration is so magnificent and the workmanship so surpassing as to defy description. The greater part is covered with gold so that the eyes of one who gazes on its beauties are dazzled by its brilliance, now glowing like a mass of light, now flashing like lightning.

Great Mosque (Masjid-e Jameh)

Isfahan, Iran. Islamic, Persian: Seljuk, Il-Khanid, Timurid and Safavid Dynasties. c. 700 C.E.; additions and restorations in the 14th, 18th, and 20th centuries C.E. Stone, brick, wood, plaster, and glazed ceramic tile

The Great Mosque of Isfahan in Iran is unique in this regard and thus enjoys a special place in the history of Islamic architecture. Its present configuration is the sum of building and decorating activities carried out from the 8th through the 20th centuries. It is an architectural documentary, visually embodying the political exigencies and aesthetic tastes of the great Islamic empires of Persia.

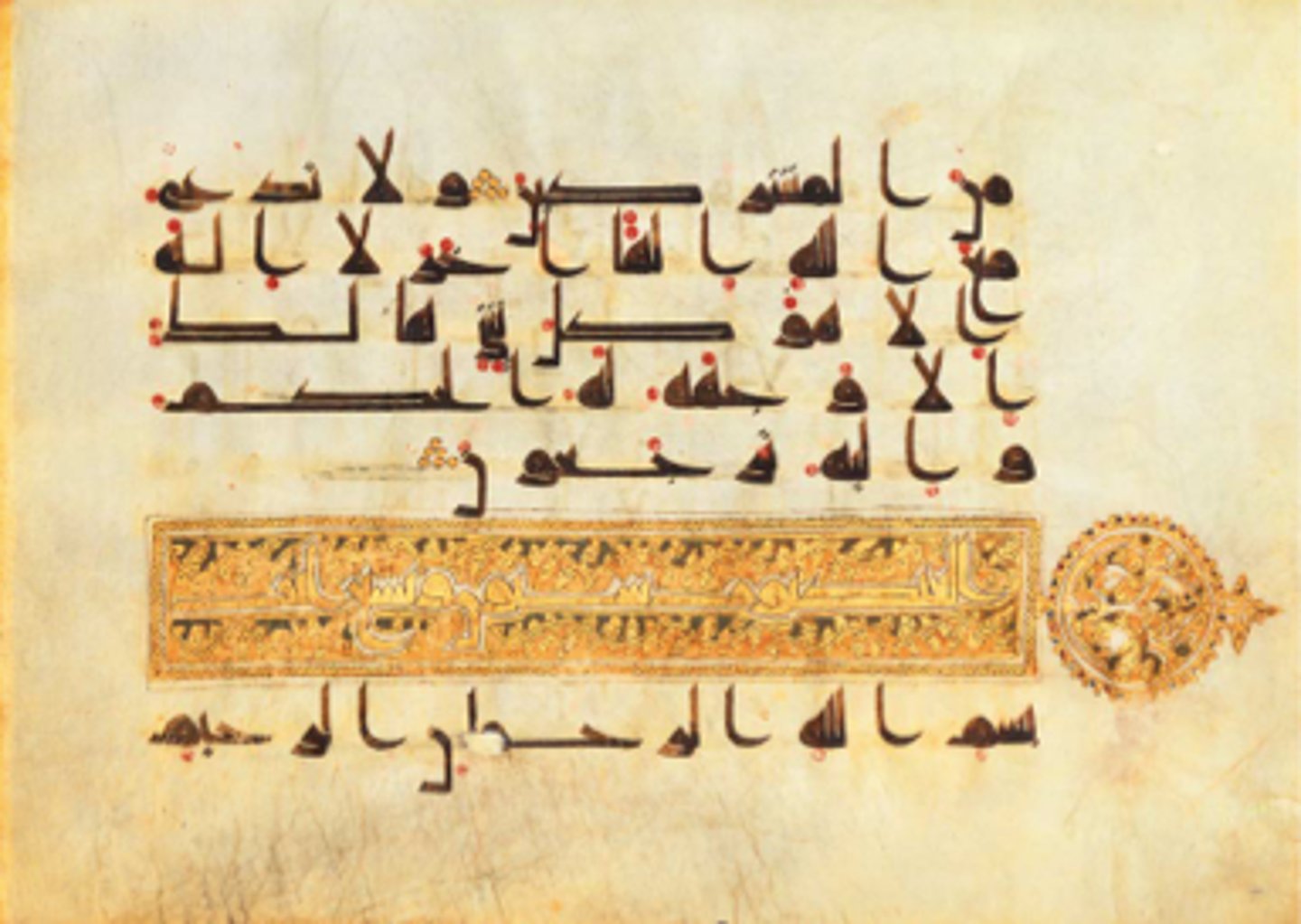

Folio from a Qur'an

Arab, North Africa, or Near East. Abbasid. c. eighth to ninth century C.E. ink, color, and gold on parchment

The Qur'an is the sacred text of Islam, consisting of the divine revelation to the Prophet Muhammad in Arabic. Over the course of the first century and a half of Islam, the form of the manuscript was adapted to suit the dignity and splendor of this divine revelation. However, the word Qur'an, which means "recitation," suggests that manuscripts were of secondary importance to oral tradition. In fact, the 114 chapters of the Qur'an were compiled into a textual format, organized from longest to shortest, only after the death of Muhammad, although scholars still debate exactly when this might have occurred.

Basin (Baptistère de Saint Louis)

Muhammad ibn al-Zain. c. 1320-1340 C.E. Brass inlaid with gold and silver

The Mamluks, the majority of whom were ethnic Turks, were a group of warrior slaves who took control of several Muslim states and established a dynasty that ruled Egypt and Syria from 1250 until the Ottoman conquest in 1517.

The political and military dominance of the Mamluks was accompanied by a flourishing artistic culture renowned across the medieval world for its glass, textiles, and metalwork.

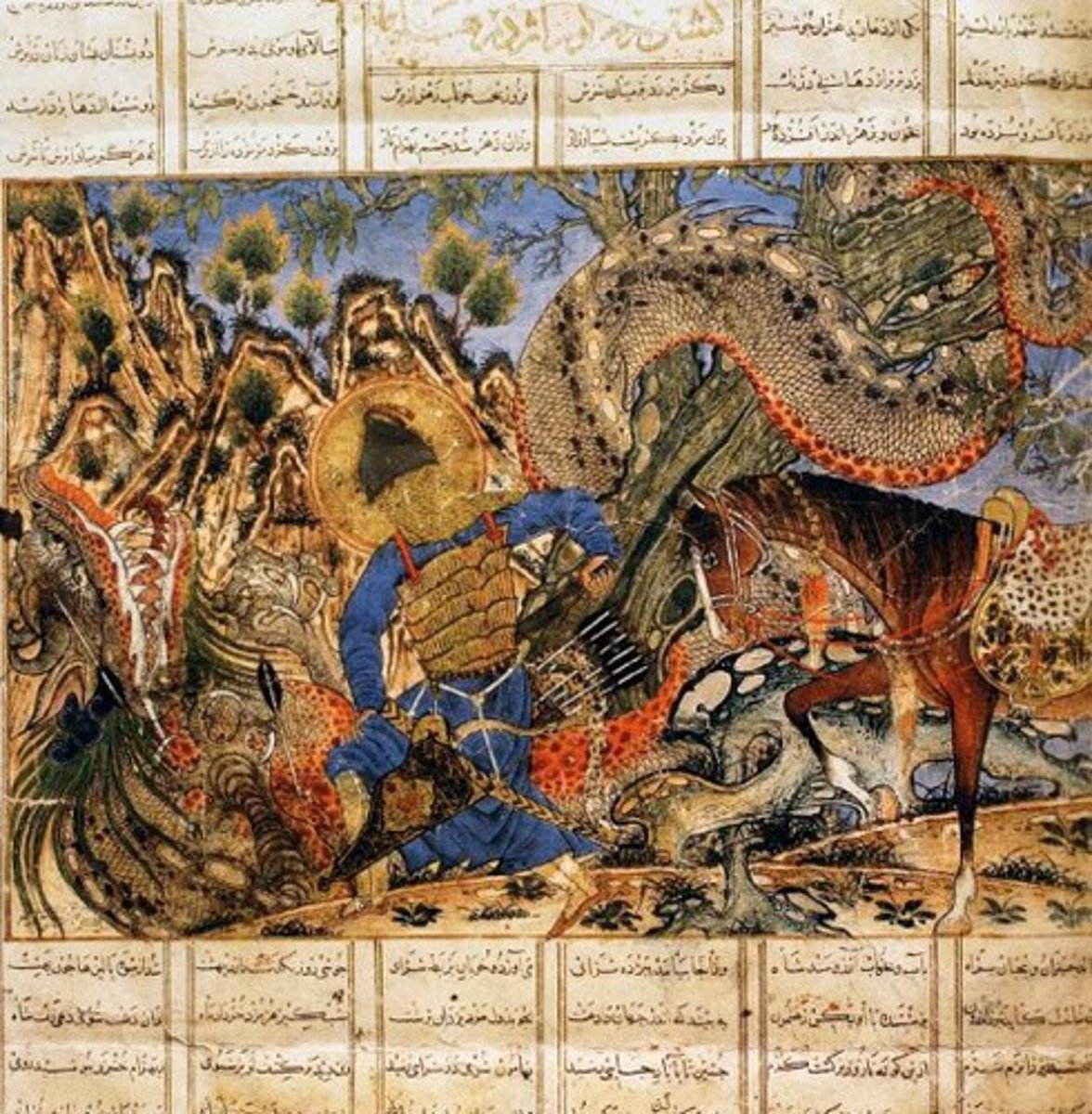

Bahram Gur Fights the Karg, folio from the Great Il-Khanid Shahnama

Islamic; Persian, Il'Khanid. c. 1330-1340 C.E. Ink and opaque watercolor, gold, and silver on paper

This folio is from a celebrated copy of the text known as the Great Ilkhanid Shahnama, one of the most complex masterpieces of Persian art. Because of its lavish production, it is assumed to have been commissioned by a high-ranking member of the Ilkhanid court and produced at the court scriptorium. The fifty-seven surviving illustrations reflect the intense interest in historical chronicles and the experimental approach to painting of the Ilkhanid period (1256-1335). The eclectic paintings reveal the cosmopolitanism of the Ilkhanid court in Tabriz, which teemed with merchants, missionaries, and diplomats from as far away as Europe and China. Here the Iranian king Bahram Gur wears a robe made of European fabric to slay a fearsome horned wolf in a setting marked by the conventions of Chinese landscape painting.

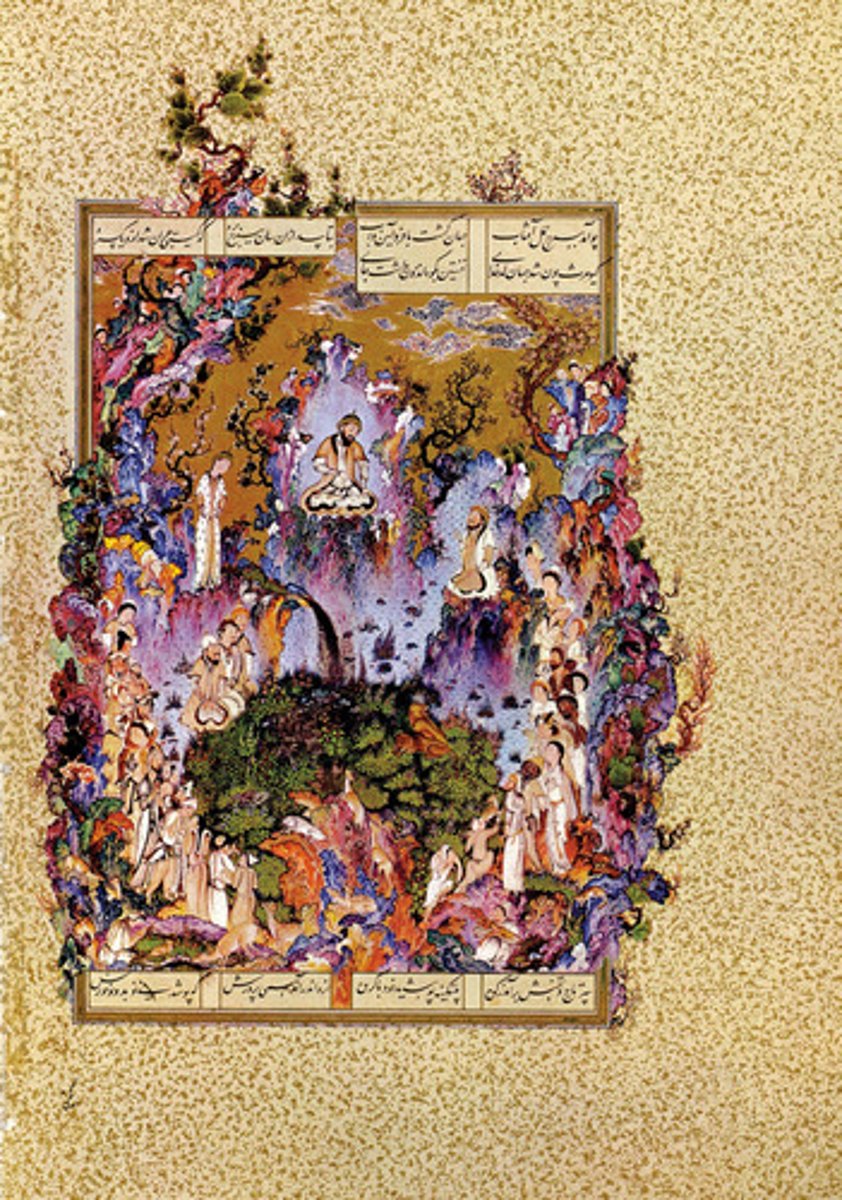

The Court of Gayumars, folio from Shah Tahmasp's Shahnama

Sultan Muhammad. c. 1522-1525 C.E. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

His painting combines an ingenious composition with a broad palette dominated by cool colors, each element minutely and precisely rendered in a technique that defies comprehension. Though the painting is large and even spills out into the gold-flecked margins, Sultan Muhammad populates the scene with countless figures, animals, and details of landscape, but in such a way that does not compromise legibility. The level of detail is so intense that the viewer is scarcely able to absorb everything, no matter how closely he looks

The Ardabil Carpet

Maqsud of Kashan. 1539-1540 C.E. Silk and wool

The Ardabil Carpet is exceptional; it is one of the world's oldest Islamic carpets, as well as one of the largest, most beautiful and historically important. It is not only stunning in its own right, but it is bound up with the history of one of the great political dynasties of Iran.

Great Stupa at Sanchi

Madhya Pradesh, India. Buddhist; Maurya, late Sunga Dynasty. c. 300 B.C.E. - 100 B.C.E. Stone masonry, sandstone on dome

It was probably begun by the Mauryan emperor Ashoka in the mid-3rd century bce and later enlarged. Solid throughout, it is enclosed by a massive stone railing pierced by four gateways, which are adorned with elaborate carvings (known as Sanchi sculpture) depicting the life of the Buddha.

Terra cotta warriors from mausoleum of the first Qin emperor of China

Qin Dynasty. c. 221-209 B.C.E. Painted terra cotta

One of the most extraordinary features of the terracotta warriors is that each appears to have distinct features—an incredible feat of craftsmanship and production. Despite the custom construction of these figures, studies of their proportions reveal that their frames were created using an assembly production system that paved the way for advances in mass production and commerce.

Funeral banner of Lady Dai (Xin Zhui)

Han Dynasty, China. c. 180 B.C.E. Painted silk

In the mourning scene, we can also appreciate the importance of Lady Dai's banner for understanding how artists began to represent depth and space in early Chinese painting. They made efforts to indicate depth through the use of the overlapping bodies of the mourners. They also made objects in the foreground larger, and objects in the background smaller, to create the illusion of space in the mourning hall.

Longmen caves

Luoyang, China. Tang Dynasty. 493-1127 C.E. Limestone

the aesthetic elements and features of the Chinese cave temples' art, including the layout, material, function, traditional technique and location, and the intrinsic link between the layout and the various elements have been preserved and passed on. Great efforts have been made to maintain the historical appearance of the caves and preserve and pass on the original Buddhist culture and its spiritual and aesthetic functions, while always adhering to the principle of "Retaining the historic condition".

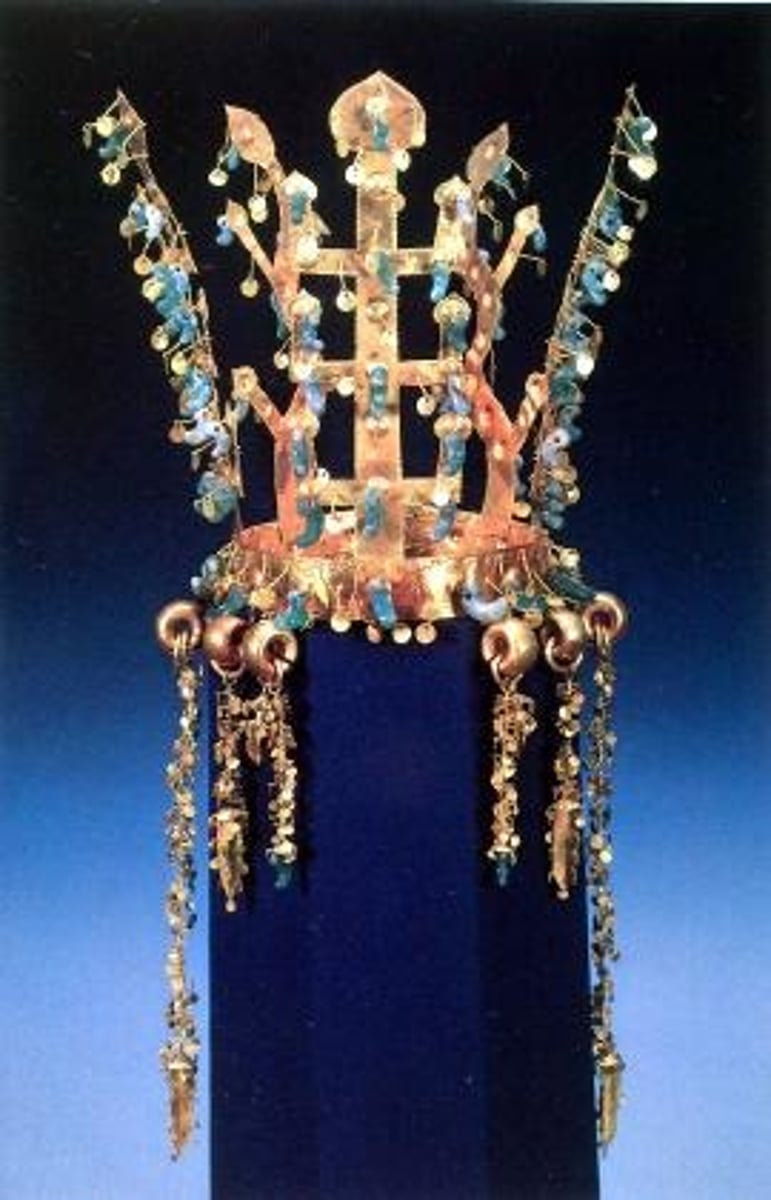

Gold and jade crown

Three Kingdoms Period, Silla Kingdom, Korea. Fifth to sixth century C.E. Metalwork

The general structure and imagery of this set echo the regalia used by rulers of the many nomadic confederations that roamed the Eurasian steppes for millennia, and, to a lesser extent, pieces found in China. However, Silla tombs such as Hwangnam Daechong have yielded larger quantities and more spectacular gold adornments.

Todai-ji

Nara, Japan. Various artist, including sculptors Unkei and Keikei, as well as the Kei School. 743 C.E.; rebuilt c. 1700. Bronze and wood (sculpture); wood with ceramic-tile roofing (architecture)

Todaiji represented the culmination of imperial Buddhist architecture. Todaiji is famous for housing Japan's largest Buddha statue. It housed the largest wooden building the world has yet seen. Even the 2/3 scale reconstruction, finished in the 17th century, it remains the largest wooden building on earth today.

Borobudur Temple

Central Java, Indonesia. Sailendra Dynasty. c. 750-842 C.E. Volcanic-stone masonry

The temple sits in cosmic proximity to the nearby volcano Mt. Merapi. During certain times of the year the path of the rising sun in the East seems to emerge out of the mountain to strike the temple's peak in radiant synergy. Light illuminates the stone in a way that is intended to be more than beautiful. The brilliance of the site can be found in how the Borobudur mandala blends the metaphysical and physical, the symbolic and the material, the cosmological and the earthly within the structure of its physical setting and the framework of spiritual paradox.

Angkor, the temple of Angkor Wat, and the city of Angkor Thom, Cambodia

Hindu, Angkor Dynasty. c. 800-1400 C.E. Stone masonry, sandstone

Angkor is one of the most important archaeological sites in South-East Asia. There were many changes in architecture and artistic style at Angkor, and there was a religious movement from the Hindu cult of the god Shiva to that of Vishnu and then to a Mahayana Buddhist cult devoted to the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara.

Lakshmana Temple

Khajuraho, India. Hindu, Chandella Dynasty. c. 930-950 C.E. Sandstone

Though the temple is one of the oldest in the Khajuraho fields, it is also one of the most exquistely decorated, covered almost completely with images of over 600 gods in the Hindu Pantheon. The main shrine of the temple, which faces east, is flanked by four freestanding subsidiary shrines at the corners of the temple platform.