Baroque art (Final exam)

1/216

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

217 Terms

Portrait of an Elderly Man

Anthony van Dyck

1618

Period/Movement

Flemish Baroque

Van Dyck was active during the Baroque period, a time marked by dramatic expression, realism, and emphasis on the human figure. By 1618, van Dyck had already become a prominent figure in Peter Paul Rubens’ workshop in Antwerp and was beginning to develop his own elegant portrait style that would soon distinguish him across Europe.

Medium

Oil on Canvas

Van Dyck’s mastery of oil paint allowed him to render soft textures, expressive faces, and luminous flesh tones—qualities that are evident in this portrait.

Current Location

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

Context

This portrait was painted when van Dyck was only around 19 years old, showcasing his precocious talent and his rising status as a portraitist. He was already working in Rubens' workshop, absorbing the grand Baroque style and refining his own distinctive approach to character and elegance.

The subject is unknown, but the focus on the sitter’s age, expression, and wisdom suggests a humanist interest in the psychological depth of the individual, rather than a mere record of social rank.

Composition and Form

The seated man, dressed in dark, formal clothing with a modest white collar, is depicted in a three-quarter view.

The background is neutral, allowing the viewer to focus on the sitter’s face and hands—key expressive features in Baroque portraiture.

Van Dyck uses subtle chiaroscuro to model the forms, giving a sense of depth and presence while maintaining a refined elegance.

Themes and Symbolism

Dignity in Aging: The subject’s lined face and solemn gaze evoke dignity, experience, and inner strength. Unlike more theatrical Baroque portraits, this work is subdued and contemplative.

Naturalism and Psychological Insight: Rather than idealizing the sitter, van Dyck emphasizes his humanity. This reflects a growing interest in the individual and a humanist appreciation for character.

Style

The portrait reflects influence from Rubens, particularly in its naturalism and soft handling of flesh and fabric.

Van Dyck’s emerging elegant and refined portrait style—which would later become synonymous with the English court—is evident in the sitter’s posture and expressive face.

The restrained color palette and the focus on mood over ornamentation distinguish this work from the more exuberant tendencies of High Baroque portraiture.

Function

Likely a private commission, possibly meant for familial remembrance or to honor the subject's wisdom and stature in life.

The intimate size and naturalistic execution suggest it was intended for personal rather than public display.

Legacy and Influence

This portrait is an early example of van Dyck’s ability to combine empathy, elegance, and psychological realism, qualities that would make him the preeminent court portraitist of Charles I of England in the following decades.

His influence would resonate across England and the Continent, shaping portraiture well into the 18th century.

Christ Crowned with Thorns

Anthony van Dyck

ca. 1620

Period/Movement

Flemish Baroque

Painted around the time van Dyck had just returned from his first Italian journey (c. 1621), this work reflects both the emotional intensity of the Baroque and the influence of Italian masters, especially Titian and Veronese, blended with the dramatic realism of Rubens.

Medium

Oil on Canvas

Current Location

Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain

Context

This painting is one of several religious works van Dyck produced early in his career, during or just before his time in Italy.

Influenced by Rubens’ dynamic figures and Italian coloration and composition, van Dyck here balances Flemish realism with a venetian softness and luminosity.

The subject, Christ mocked and crowned with thorns before his crucifixion, was a common devotional image in Counter-Reformation art—designed to inspire empathy, penitence, and reflection.

Composition and Form

Christ is seated in the center, surrounded by soldiers who press a crown of thorns onto his head. The pose is passive and sorrowful, emphasizing his suffering and humility.

The figures crowd the canvas, their gestures and facial expressions full of aggression or contempt, while Christ’s face is calm and resigned.

Van Dyck uses diagonal composition, contrasting light and shadow (tenebrism), and muscular, expressive bodies, in a style reminiscent of both Rubens and Caravaggio.

Themes and Symbolism

Sacrifice and Redemption: The crown of thorns is a clear symbol of Christ’s willing suffering for humanity’s sins.

Contrast of Divine and Human: The calm, idealized Christ contrasts sharply with the rough, emotional tormentors—reflecting the theme of innocence persecuted.

Emotional Realism: The image is meant to evoke empathy and devotional reflection, central goals of Baroque religious art in the post-Tridentine world.

Style

Strong Caravaggesque lighting, with dark background and light hitting key figures (especially Christ).

Influences from Titian in the color palette and Rubens in the energetic forms and twisting bodies.

Van Dyck blends Baroque drama with refined elegance, especially in the rendering of Christ’s flesh and features.

Function

Likely commissioned as an altarpiece or private devotional painting, meant to aid in spiritual contemplation and emotional engagement with the Passion of Christ.

Fits into Counter-Reformation goals of using art to instruct and move the faithful through powerful, affective imagery.

Legacy and Influence

One of van Dyck’s early masterpieces in religious art, it shows his mastery of pathos and form before turning more fully to portraiture in the 1620s.

Helped solidify his international reputation, especially in Italy and Spain, where this kind of deeply emotional devotional image was in high demand.

Madonna of the Rosary

Anthony van Dyck

1624-26

Period/Movement

Flemish Baroque

This work comes from van Dyck’s mature Italian period, specifically while he was in Palermo, Sicily, during a time of plague. It reveals the influence of Titian, Rubens, and the broader goals of the Counter-Reformation.

Medium

Oil on canvas

Current Location

Oratorio del Rosario di Pompei, Palermo, Sicily

Context

Painted during van Dyck’s Italian travels, Madonna of the Rosary was commissioned by a Dominican brotherhood during a plague outbreak. The subject was deliberately chosen for its spiritual association with protection and intercession.

The rosary was a powerful devotional tool promoted by the Dominicans, and images of the Madonna distributing it symbolized divine grace and healing.

Van Dyck had fled to Palermo in 1624 to escape plague in mainland Italy, only to encounter another outbreak—this work is deeply tied to that context of faith amidst crisis.

Composition and Form

The Virgin and Child are enthroned high above, seated on clouds and surrounded by putti (cherubs), distributing rosaries.

Below, St. Dominic and St. Catherine of Siena (key Dominican saints) distribute rosaries to the faithful. The saints are idealized, yet grounded in human emotion and realism.

The composition has a vertical, pyramidal structure, drawing the eye upward to the Virgin, symbolizing heavenly intercession and salvation.

The use of rich Venetian color, soft modeling, and atmospheric light reflects van Dyck’s study of Titian and Veronese, with added Flemish detail and dynamism.

Themes and Symbolism

Intercession: The Virgin acts as a mediator between heaven and earth, offering the rosary as a spiritual lifeline during the plague.

Faith and Protection: The act of distributing the rosary reflects Catholic doctrine that prayer and devotion offer divine protection and grace.

Triumphant Virgin: Seated above, Mary also evokes the Queen of Heaven, reinforcing her exalted status in Catholic devotion.

Style

Combines Italian coloration with Flemish emotional realism.

Strong diagonal lines, luminous skin tones, graceful gestures, and richly draped fabrics.

Figures are elegant and idealized—hallmarks of van Dyck’s mature religious style—while still conveying emotion and naturalistic presence.

Function

Served as a public altarpiece for the Dominican Oratory, reinforcing devotion to the rosary and offering spiritual solace during the plague.

Aimed at eliciting empathy, piety, and awe—key goals of Baroque religious art aligned with Counter-Reformation ideals.

Legacy and Influence

This painting helped cement van Dyck’s reputation in Italy and led to further commissions.

It showcases his successful synthesis of Italian grandeur and Flemish sensitivity, and anticipates the courtly elegance he would later bring to English portraiture.

Sacra conversazione

Meaning "holy conversation" in Italian, refers to a specific type of religious artwork, particularly a painting. It depicts the Virgin Mary and the infant Jesus surrounded by saints, often in a unified space, engaged in a "conversation" or interaction. This artistic form replaced the polyptych (multiple panel altarpiece) during the Renaissance, offering a new way to portray the Christian community across time and space.

Cardinal Guido Bentivoglio

Anthony van Dyck

1622-27

Medium

Oil on canvas

Current Location

Palazzo Pitti, Florence

Historical Context

Painted during van Dyck’s extended stay in Italy, this portrait shows the influence of Titian and Rubens, particularly in its rich color palette, psychological depth, and sophisticated elegance.

Guido Bentivoglio (1579–1644) was a prominent Cardinal, papal diplomat, and historian. Known for his intellect and statesmanship, he served as nuncio in Flanders, where he became a patron and acquaintance of Rubens—creating a direct connection to van Dyck’s Flemish world.

This portrait may have been commissioned shortly after Bentivoglio’s return to Rome in 1618 and reflects van Dyck’s ability to capture the authority and refinement of elite sitters.

Formal Analysis

Pose & Composition: Bentivoglio is depicted seated in a dignified, three-quarter pose, turned slightly to his right, with a calm but commanding expression. His right hand rests lightly on the armrest, the left possibly holding a letter—subtly referencing his diplomatic and intellectual career.

Color & Texture: Van Dyck masterfully renders the deep crimson robes of a cardinal, with meticulous attention to texture, light, and layering. The satin glows under soft light, adding a sense of richness and physicality.

Background: Neutral, dark, and unobtrusive—enhancing the prominence of the cardinal and lending a sense of gravitas and introspection.

Expression: The sitter's calm, intelligent gaze, slightly raised eyebrows, and parted lips suggest both alertness and self-assurance, revealing van Dyck’s gift for psychological nuance.

Style

A superb example of Baroque portraiture, combining Flemish realism with the elegance and restraint of the Italian high style.

Influences include Titian’s portraits of Venetian nobility, seen in the rich fabrics and subtle modeling of the face.

Van Dyck's hallmark characteristics are present: elongated figures, refined hands, and a fluid, painterly surface.

Themes and Symbolism

Power and Prestige: Bentivoglio’s rank is announced through both his cardinal’s robes and the serenity of his pose—he is in control, dignified, a representative of church and intellect.

Diplomacy and Learning: The inclusion of a letter or paper (if present) subtly nods to his roles in international negotiation and his authorship of historical texts.

Human Presence: Unlike some colder court portraits, van Dyck’s sitter feels real—he breathes, thinks, and reflects, aligning with the Baroque ideal of emotional connection.

Function

Likely intended as an official portrait to commemorate Bentivoglio’s elevated status and role within the papal court.

Reinforced his political and intellectual authority, possibly for public display in his residence or as a diplomatic gift.

Legacy and Influence

This work showcases van Dyck’s development into one of the premier portraitists of his age, soon to be tapped by Charles I of England.

The painting helped shape the Baroque ideal of noble portraiture—dignified yet personal, stately yet alive.

It influenced later papal and ecclesiastical portraiture, echoing even into 18th-century depictions of clerics.

Elena Grimaldi

Anthony van Dyck

Marchesa Cattaneo

1623

Medium

Oil on canvas

Current Location

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Historical Context

Painted during van Dyck’s Italian period (1621–27), specifically while he was working in Genoa, a wealthy port city known for its patronage of foreign artists.

The Grimaldi and Cattaneo families were among Genoa’s elite, and portraiture was a way to project status, lineage, and refinement.

This portrait was commissioned at a time when van Dyck was actively cultivating a courtly, aristocratic style, influenced by Titian and Rubens.

The Sitter

Elena Grimaldi was married into the Cattaneo family, placing her at the top of Genoese society.

Her depiction as a dignified and graceful noblewoman not only celebrates her beauty and rank but also adheres to ideals of virtue, poise, and nobility.

Formal Analysis

Pose & Composition: Elena stands full-length, turned slightly to the side with a composed and almost statuesque bearing. Her gaze is steady, yet slightly detached—appropriate for noble portraiture of the time.

Gesture & Accompaniment: She is accompanied by a black page (a common Baroque trope indicating exotic wealth), who draws back a curtain, revealing her in a formal setting. This dramatic gesture emphasizes her importance and theatrical presentation.

Attire: Her black silk gown, trimmed with lace and gold, and her elaborate jewelry indicate extreme wealth and refinement. The dress’s shimmering material and stiff structure heighten her formality.

Color & Light: Van Dyck uses a limited, luxurious palette—deep blacks, golds, and whites—with silvery highlights. Light reflects softly on her skin and fabrics, giving the figure a regal glow.

Setting: The inclusion of a balustrade and curtain creates a stage-like effect, enhancing the portrait's performative quality.

Style

Shows van Dyck’s shift toward the Italian Baroque elegance seen in the works of Titian, especially in full-length noble portraits.

Compared to his earlier Flemish works, this portrait is more stylized and idealized, favoring graceful elongation and subtle theatricality.

The vertical format and grand scale align with contemporary traditions of noble representation.

Themes and Symbolism

Nobility and Refinement: Every aspect of Elena’s appearance communicates wealth, status, and decorum.

Power and Exoticism: The presence of the Black page signals not only colonial wealth but also serves to highlight the sitter’s whiteness and importance—a complex racial and social dynamic typical of elite European portraiture.

Stage and Spectacle: The curtain being drawn aside reflects the Baroque fascination with illusion, performance, and grandeur.

Function

Commissioned to document and display social status, beauty, and family prominence.

Likely hung in a palazzo or reception space where visitors would encounter the image as a visual declaration of the family’s elite position.

Legacy and Influence

A key example of van Dyck’s Genoese portraits, which influenced Italian and Northern European portraiture alike.

Helped establish the aristocratic portrait model—full-length, elegant, with a balance of formality and liveliness—that van Dyck would later perfect in England.

Reflects the globalized, hierarchical world of 17th-century Europe, where art, status, and empire intersected.

Virgin and Child with Sts. Paul, Peter, and Rosalie

Anthony van Dyck

1629

Medium

Oil on canvas

Current Location

Galleria Nazionale della Sicilia (Palazzo Abatellis), Palermo, Italy

Historical and Religious Context

Commissioned while van Dyck was active in Palermo, Sicily, during his stay in Southern Italy between 1624 and 1629.

This period coincided with a plague outbreak, during which Saint Rosalie, a local saint of Palermo, was venerated for her miraculous protection against the disease.

The painting reflects a plague ex-voto tradition, where artworks were created as offerings of thanksgiving or as petitions for divine intervention during times of crisis.

Subject and Iconography

Virgin and Child: Positioned at the center and elevated, representing divine authority, grace, and intercession. The Virgin gestures with maternal tenderness, while the Christ Child often extends a blessing or interacts with the saints below.

St. Peter: Usually shown with keys, a symbol of his authority and role as gatekeeper of heaven.

St. Paul: Identified by his sword, referencing both his martyrdom and his role as a militant apostle of the faith.

St. Rosalie: Portrayed in a contemplative and humble posture, dressed as a hermit with long flowing hair and a wreath of flowers or roses—her symbols as the patron saint of Palermo.

Formal Analysis

Composition: Strongly vertical, with the holy figures placed in a heavenly realm above and the saints arranged below, creating a spiritual hierarchy. The viewer’s gaze is drawn upward to the Virgin and Child.

Color Palette: Rich but softened—deep reds, muted blues, earthy browns, and glowing skin tones. The ethereal lighting and gentle contrasts lend the work a warm, devotional atmosphere.

Use of Light: A subtle divine radiance emanates from the Virgin and Child, enhancing their sanctity. The lighting adds volume and dignity to the figures without overt drama.

Gesture and Expression: Calm and reverent. Each saint appears absorbed in devotion, reflecting inner piety rather than outward emotion—typical of Van Dyck’s religious works.

Style

Reflects a synthesis of Italian Baroque influence (especially Titian and Correggio) with van Dyck’s Flemish sensitivity to texture and emotion.

Compared to his earlier works, this painting exhibits a gentler elegance and spiritual serenity, a hallmark of his mature religious compositions.

The figures are idealized but individualized, creating a sense of both the sacred and the accessible.

Function

Likely intended for a private or public devotional space, possibly commissioned as a plague-related votive offering to honor Saint Rosalie’s intercession.

Served to inspire prayer and veneration in a time of communal suffering, providing both visual beauty and spiritual comfort.

Legacy

A significant work from van Dyck’s Palermitan period, where he adapted his portraiture skills to large-scale, multi-figure religious compositions.

Demonstrates van Dyck’s ability to blend Flemish detail and Italian grandeur, making him a key figure in the development of international Baroque painting.

The inclusion of Saint Rosalie, relatively rare outside of Palermo, also links this piece to a specific moment in Sicilian religious history and van Dyck’s direct response to it.

Rinaldo and Armida

Anthony van Dyck

1629

Medium

Oil on canvas

Current Location

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

Literary and Mythological Context

Based on Jerusalem Delivered (La Gerusalemme Liberata, 1581), an epic poem by Torquato Tasso.

Tasso’s poem blends Christian crusade narrative with romantic fantasy, following the exploits of Christian knights during the First Crusade.

The story of Rinaldo and Armida is one of its most famous subplots:

Rinaldo, a Christian knight, is seduced and enchanted by the sorceress Armida, an enemy of the crusaders.

She brings him to her magical garden to distract him from his divine mission.

Eventually, other knights find Rinaldo and break the spell, prompting his return to duty.

The tale balances themes of love, temptation, and heroic virtue.

Subject and Iconography

Van Dyck depicts the moment when Armida gazes lovingly at the sleeping Rinaldo, hesitating between killing him (as instructed) and falling in love.

Rinaldo lies nude and vulnerable, a classical pose that recalls ancient statuary, symbolizing innocence and beauty.

Armida is richly dressed and leaning over him, her dagger either drawn or cast aside—highlighting her emotional transformation.

The garden setting is lush and enchanted, visually evoking temptation and sensuality.

Cupid or putti may be present, reinforcing the themes of love and enchantment.

Formal Analysis

Composition: The diagonal positioning of Rinaldo’s body contrasts with the upright, twisting figure of Armida, creating visual tension and narrative drama.

Light and Color: Van Dyck uses a warm, golden light to model the flesh and rich fabrics. The luminous palette enhances the scene’s emotional and seductive tone.

Brushwork: Smooth and refined, particularly in the rendering of skin and textiles, showcasing Van Dyck’s Flemish roots and influence from Titian.

Emotion and Gesture: Armida’s face reflects conflict, tenderness, and awe, while Rinaldo’s peaceful slumber evokes purity and trust, increasing the dramatic irony.

Style and Influence

Strong influence from Titian and the Venetian tradition, particularly in the sensuous treatment of mythological subjects.

Van Dyck’s use of psychological nuance and expressive body language reflects his deepening maturity as an artist.

Combines Baroque theatricality with Renaissance grace, balancing spectacle with emotional depth.

Function and Patronage

Likely commissioned for a private collection, intended to entertain and intellectually engage an elite viewer familiar with Tasso’s poem.

Mythological and literary subjects were highly prized in aristocratic settings, showcasing both erudition and aesthetic sophistication.

This work provided visual pleasure, moral reflection, and classical reference—ideal for Baroque connoisseurs.

Legacy and Interpretation

One of Van Dyck’s most compelling mythological paintings.

Explores the power dynamics between genders, the tension between duty and desire, and the fine line between violence and love—all major Baroque themes.

A masterclass in narrative painting, where the viewer is drawn into a single, suspended moment full of psychological drama.

Torquato Tasso, gerusalemme liberata

Jerusalem Delivered, also known as The Liberation of Jerusalem, is an epic poem by the Italian poet Torquato Tasso, first published in 1581, that tells a largely mythified version of the First Crusade in which Christian knights, led by Godfrey of Bouillon, battle Muslims in order to take Jerusalem.

Charles I

A major figure during the Baroque period and played a significant role in the development of the art movement in England. He was a keen collector of art, particularly of the Old Masters, and is known to have commissioned works by famous Baroque artists. Notably, he employed Anthony van Dyck as his official court painter, and van Dyck created numerous portraits of Charles I and his court, showcasing the grandeur and dynamism characteristic of the Baroque style

Charles I with Monseigneur de St. Antoine

Anthony van Dyck

1633

Medium

Oil on canvas

Current Location

Royal Collection, London (Hampton Court Palace)

Context & Patronage

Commissioned by King Charles I to promote royal authority and the divine right of kings.

Van Dyck had recently been knighted and appointed "Principal Painter in Ordinary" to the king (1632).

This equestrian portrait aligns Charles I with the grandeur of Roman emperors and the chivalric ideals of Renaissance monarchs.

Monseigneur de St. Antoine was Charles’s riding master, representing discipline, nobility, and classical equestrian prowess.

Subject and Iconography

Charles I is depicted mounted on a powerful horse, dressed in gilded armor with a baton of command in hand—evoking the iconography of a victorious general or emperor.

His calm expression and noble posture project authority, while the horse's raised leg and controlled movement suggest energy under control.

M. de St. Antoine follows on foot, helmet in hand, positioned deferentially behind and slightly below the king—emphasizing hierarchy and service.

The distant landscape and dramatic sky contribute to the grandeur, suggesting a world under royal dominion.

The image blends portraiture and state propaganda, intended to exalt Charles I’s kingship and martial elegance.

Formal Analysis

Composition: Triangular structure focusing on the king and horse, with strong diagonals from lance, limbs, and gaze.

Color and Light: Rich, cool hues with metallic highlights; van Dyck renders armor with great attention to luster and reflection.

Scale and Space: Monumental; the king and horse dominate the canvas, enhancing their symbolic stature.

Naturalism vs. Idealization: Charles I’s features are true to life but idealized in bearing—combining portrait precision with classical grandeur.

Style and Influence

Inspired by Titian's equestrian portraits (e.g., Charles V at Mühlberg) and Rubens’ courtly magnificence.

Merges Flemish detail with Italianate monumentality.

Van Dyck’s signature elegance and psychological poise distinguish his royal sitters from earlier English portraiture (e.g., the stiffer style of Daniel Mytens).

Function and Message

A visual assertion of authority during a time when Charles’s rule was under scrutiny (pre-English Civil War tensions).

Communicates the ideals of divine monarchy, chivalry, and martial discipline.

Serves as a propagandistic masterpiece, reinforcing Charles’s image as the natural, rightful sovereign.

Legacy and Interpretation

One of Van Dyck’s most celebrated equestrian portraits.

Sets a standard for royal portraiture in Britain, influencing artists like Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough.

Seen as an emblem of Stuart kingship, later imbued with nostalgia and tragedy after Charles I’s execution in 1649.

The Duke of Lerma

Peter Paul Rubens

ca. 1603

Medium

Oil on canvas

Current Location

Museo del Prado, Madrid

Historical Context

Created during Rubens’s diplomatic visit to Spain in 1603 as an envoy from the Duke of Mantua.

The sitter, Francisco Gómez de Sandoval y Rojas, Duke of Lerma, was the powerful favorite (valido) of King Philip III of Spain, effectively running the kingdom.

The painting was part of Rubens’s early career and helped establish his international reputation.

Subject & Iconography

The Duke of Lerma is shown on horseback, dressed in elaborate armor, with a marshal’s baton, commanding the viewer's attention as a ruler and military leader.

His horse rears dynamically, evoking Roman imperial imagery and reinforcing his dominant political role.

He is framed by a dramatic landscape and sky, contributing to the heroic, triumphal tone.

Visual & Formal Analysis

Composition: Classic triumphal equestrian format, with strong diagonals in horse’s body and the baton guiding the viewer’s eye.

Color and Texture: Rich, velvety fabrics and glistening metal; Rubens’s painterly surface creates depth and opulence.

Light and Atmosphere: A strong use of chiaroscuro emphasizes both realism and theatricality, placing the Duke in a near-divine glow.

Pose and Gesture: The Duke’s posture is upright, serene, and confident—a blend of naturalism and idealized authority.

Influence & Style

Reflects Rubens’s exposure to Titian and Venetian colorism, merged with his own emerging Baroque dynamism.

Anticipates the grandeur of later equestrian portraits (e.g., Rubens’s Charles V at Mühlberg, 1620s) and influences van Dyck's Charles I equestrian paintings.

Function & Message

Serves as a political and propagandistic portrait, glorifying Lerma’s de facto power over Spain.

Reinforces the iconography of martial nobility, linking Lerma to Roman emperors and Christian knightly ideals.

The painting asserts Lerma’s personal prestige as much as his institutional authority.

Legacy & Significance

One of Rubens’s earliest major state portraits, revealing his diplomatic skill as well as artistic prowess.

Sets a precedent for the Baroque equestrian portrait, combining monumentality, grace, and theatrical narrative.

Offers a visual record of early 17th-century Spanish court culture, filtered through the lens of Flemish flair.

Le Roi a la Chasse (The King at the Hunt)

Anthony van Dyck

1635

Medium

Oil on canvas

Current Location

Louvre Museum, Paris

Patron & Subject

Commissioned by or for King Charles I of England, van Dyck’s chief patron.

Charles is shown as an elegant gentleman hunter, not in military dress, emphasizing refined kingship rather than martial prowess.

The figure is flanked by two attendants and a horse, set in a lush countryside—symbolic of royal dominion over land and leisure.

Historical & Political Context

Painted during a period of increasing political tension in England, just a few years before the English Civil War.

This portrait subtly reinforces Charles’s divine right and royal poise, while offering a less formal, more natural image of kingship.

Reflects courtly ideals of nobility and cultured refinement, crucial to Charles’s self-image and propaganda.

Visual & Formal Analysis

Composition: Charles stands off-center, facing the viewer with a slight contrapposto stance, allowing his elegance to dominate the space without grandeur.

Gesture: One hand rests on his hip, the other holds a walking stick—calm, controlled, subtly authoritative.

Attire: Not in armor, but richly dressed in leisure clothing with high boots and a plumed hat, exemplifying courtly fashion.

Landscape: A calm, sweeping English countryside, evoking harmony, nobility, and stewardship.

Lighting: Soft and atmospheric, highlighting the textures of Charles’s clothing and the serene ambiance.

Stylistic Characteristics

Strong influence from Titian and Rubens in color, pose, and landscape integration.

Van Dyck’s signature refined, aristocratic naturalism—the king appears both idealized and realistic.

Lacks overt symbolism or allegory, yet exudes authority through composition and elegance.

Function & Message

A non-military image of monarchy, highlighting taste, control, and noble demeanor.

Projects absolute monarchy through aesthetic confidence rather than force.

Meant to portray Charles as God’s chosen ruler, capable of ruling with grace and harmony.

Comparative Notes

Contrasts with Rubens’s Duke of Lerma or Equestrian Portrait of Charles V, which depict military authority.

Closer in tone to Velázquez’s informal court portraits or Gainsborough’s later naturalistic aristocrats.

A companion piece to van Dyck’s Charles I on Horseback (1637), but this one is more intimate and approachable.

Legacy & Significance

One of the most iconic royal portraits of the 17th century.

Helped define the image of the Stuart monarchy, influencing court portraiture for decades.

Van Dyck’s treatment became the standard for aristocratic portraiture—elegant, poised, and subtly powerful.

waterschilder

watercolor painter

Holy Family with St. John the Baptist

Jacob Jordaens

ca. 1620

Medium

Oil on canvas

Overview

This painting presents a domestic, intimate vision of the Holy Family—Mary, Joseph, the Christ Child, and the young St. John the Baptist—interacting in a warm, naturalistic setting. It exemplifies the Flemish Baroque approach to religious themes: emotionally immediate, physically robust, and suffused with light and vitality.

Visual & Formal Analysis

Composition: The figures are gathered in a tight, pyramidal group, enhancing a sense of intimacy.

Emotion & Interaction: The expressions are affectionate and focused on the children, emphasizing familial bonds. The Virgin often looks tenderly at Jesus, while Joseph and John form the outer framework, directing attention inward.

Children: The Christ Child and John the Baptist are rendered with rosy vitality, playfully engaging with each other—Jordaens often portrayed children with a slightly stocky and exuberant realism.

Light & Color: Rich, warm tones dominate—reds, ochres, and earthy browns—with strong chiaroscuro to model the figures and create a sense of three-dimensionality. The lighting focuses on the central figures, enhancing their spiritual presence while maintaining a naturalistic atmosphere.

Setting: The background is either neutral or softly suggests a domestic interior, reinforcing the humanized, relatable nature of the Holy Family.

Stylistic Characteristics

Influenced by Rubens in terms of muscular forms, emotional expressiveness, and compositional structure.

Jordaens’s style is more robust and grounded, lacking the idealized elegance of van Dyck.

His figures exude a Flemish earthiness, rooted in genre scenes and daily life, giving sacred stories a real-world immediacy.

Function & Message

Intended to inspire devotional intimacy—viewers could connect with the Holy Family not only as sacred figures but also as models of love, tenderness, and domestic virtue.

Reinforces Catholic values of the Counter-Reformation: the sanctity of family, the humanity of Christ, and accessible spirituality.

St. John the Baptist’s presence also alludes to his later role as Christ’s forerunner, though here he is shown as a child—innocence foreshadowing destiny.

Context

Produced during a time when religious art in the Spanish Netherlands was being used to reaffirm Catholic doctrine and encourage personal piety in the wake of the Reformation.

Jordaens, though never traveling to Italy, responded directly to the Italianate trends set by Rubens and Caravaggio, favoring drama, naturalism, and emotional connection.

Comparative Notes

Similar in tone to Rubens’s Holy Family under the Apple Tree or Rest on the Flight into Egypt.

Contrasts with Caravaggio’s more austere, psychological interpretations—Jordaens is lusher and more familial.

Shares thematic resonance with Murillo’s later Spanish Holy Family paintings, though with more physicality and less ethereal softness.

Madonna of the Rosary

Caravaggio

1607

Medium

Oil on canvas

Current Location

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Commission & Context

Likely commissioned by a member of the Dominican Order, given the central presence of St. Dominic and the theme of the Rosary.

Created during Caravaggio’s Neapolitan period, marked by a heightened theatricality, grander scale, and more public, communal religious works, in contrast to his earlier private commissions.

This period reflects Caravaggio’s own sense of vulnerability, exile, and a new intensity in his spiritual subjects.

Subject Matter

At the center, the Virgin Mary, seated on a throne with the Christ Child, hands a rosary to St. Dominic (right), the founder of the Dominican Order.

On the left stands St. Peter Martyr, with his palm of martyrdom.

A crowd of supplicants, including a donor (possibly the commissioner), kneels or stands at the bottom, receiving rosaries or gazing upward in awe.

The scene symbolizes the spiritual and salvific power of the Rosary, a key tool of Counter-Reformation devotion.

Formal Analysis

Composition: Monumental, pyramidal, and staged like a sacred theater. The Virgin is enthroned at the apex, visually anchoring the composition.

Chiaroscuro: Caravaggio’s signature tenebrism is fully developed—sharp contrasts between light and dark pull focus to the Virgin, Christ, and saints, while the background is engulfed in shadow.

Color: Rich, saturated reds dominate the Virgin’s cloak and the curtain above—perhaps symbolic of martyrdom and divine authority. Earth tones in the lower figures ground the scene in realism.

Naturalism: The faces and gestures of the figures are unidealized, drawn from real people. The supplicants display emotional urgency—wide eyes, clasped hands, and pleading expressions.

Hierarchy: The painting carefully orchestrates viewer response—divine figures above, humans below, emphasizing intercession and grace through the saints.

Theological & Iconographic Meaning

Promotes Marian devotion and the power of the Rosary to guide souls toward salvation—a key message of Counter-Reformation Catholicism.

The dominance of St. Dominic and St. Peter Martyr reflects the Dominican mission to combat heresy and spread the Rosary devotion.

The human figures below underscore the idea that divine grace is mediated through Church figures—saints as intercessors.

The curtain, dramatically pulled back, suggests a theatrical revelation of the sacred, reinforcing Baroque notions of spectacle and divine immediacy.

Function & Audience

Meant for public display, likely an altarpiece or church commission.

Served both a didactic function (educating about the Rosary’s power) and a devotional one (inspiring prayer and awe).

The inclusion of a donor portrait links the work directly to its patron’s piety and social status.

Comparative Notes

Compositional grandeur and vertical hierarchy are similar to Titian’s and Venetian altarpieces, which Caravaggio would have known.

The theatricality and deep emotional realism align with Caravaggio’s contemporaneous works like the Seven Works of Mercy (1607), also painted in Naples.

Unlike earlier, more intimate Caravaggios, this piece engages a broader communal spirituality, in line with post-Tridentine ideals.

The Calling of Sts. Peter and Andrew

Jacob Jordaens

ca. 1618

Medium

Oil on canvas

Current Location

Museo del Prado, Madrid

Subject Matter

A biblical scene from the Gospels (primarily Matthew 4:18–22 and Mark 1:16–20), where Christ calls the fishermen brothers, Peter and Andrew, to become his disciples, saying:

“Follow me, and I will make you fishers of men.”Christ stands on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, gesturing to Peter and Andrew, who respond with surprise, humility, and attention.

Formal Analysis

Composition: A tightly framed scene with three main figures. Christ, at the left, gestures calmly yet authoritatively, while Peter and Andrew, kneeling or leaning toward him, respond with astonishment.

Light and Color: Influenced by Caravaggisti tenebrism—strong light-dark contrast, especially in the faces and garments. The earthy tones of the fishermen contrast with Christ’s slightly more idealized, luminous form.

Figures:

Christ is shown in a calm, idealized manner, with flowing drapery and a commanding pose.

Peter and Andrew are burly, rugged, and realistic—depicted as laborers, not idealized saints.

Their expressive faces and dynamic gestures reflect emotional immediacy and humanity.

Naturalism: The sea, fishing net, and muscularity of the figures anchor the work in real-world physicality, consistent with Jordaens’ style and Flemish realism.

Gesture & Movement: The moment is suspended at the peak of narrative action—Christ’s calling hand, the brothers’ reactions, and the physical weight of their bodies in motion.

Theological & Iconographic Meaning

The moment of divine calling highlights obedience, humility, and the transformative power of Christ’s word.

Peter and Andrew’s response—immediate and unquestioning—emphasizes apostolic authority and devotion, key messages in Counter-Reformation art.

Their depiction as ordinary men supports the notion that holiness is accessible to all, not reserved for the elite.

Comparative Notes

Jordaens’ Caravaggesque realism contrasts with Rubens’ more idealized and heroic figures.

Similar themes of calling or conversion are found in Caravaggio’s Calling of St. Matthew (1599–1600), though Jordaens replaces urban settings with a natural, seaside context.

Unlike earlier depictions, which might render the apostles more symbolically, Jordaens gives them flesh and labor, anchoring the spiritual moment in the material world.

Related in tone to early Rubens works such as The Miraculous Draught of Fishes (1610s), though Jordaens’ style is generally more grounded and less courtly.

Function & Audience

Likely intended for a church or private devotional setting, meant to inspire reflection on divine calling and humility.

Visualizes a moment of transformation—ordinary men becoming saints through divine encounter—a popular theme in Baroque didactic art.

Rubensian

Refers to something related to or characteristic of the paintings of Peter Paul Rubens, particularly his depiction of full-figured women. It can also describe a woman's figure as being plump and curvaceous.

Portrait of a Young Married Couple

Jacob Jordaens

1615-20

Medium

Oil on canvas

Current Location

Louvre Museum, Paris

Subject Matter

A double portrait of an affluent young couple, likely from Antwerp’s merchant or patrician class.

The sitters are shown seated in a garden setting, with the woman’s hand resting on the man’s arm—a rare gesture of mutual affection and intimacy in early 17th-century portraiture.

A cherub and possibly symbolic flowers or animals appear in the composition, subtly underscoring themes of love, fertility, and harmony.

Formal Analysis

Composition: Balanced yet relaxed. The couple is arranged diagonally, lending a sense of movement and naturalism rather than rigid symmetry.

Gesture & Expression: Both figures look out toward the viewer, but their slight tilt toward one another conveys emotional closeness.

Costume:

The man is dressed in rich black velvet, with a white lace collar and cuffs, denoting status and sobriety.

The woman wears a sumptuous white satin gown with fine lace and jewelry, emphasizing wealth, purity, and elegance.

Background: A garden with trees, vines, and cherubs—symbolic of marital harmony and possibly referencing classical love allegories.

Color & Light: Warm, rich tones with soft illumination create a sense of intimacy and vitality. The textures of fabrics and skin are rendered with Baroque attention to sensual detail.

Naturalism: Jordaens captures individualized features, subtle gestures, and lifelike textures, elevating the portrait above courtly idealization.

Influence of Rubens: Seen in the lush garden, sensual textures, and use of mythological elements to frame the domestic.

Iconographic & Cultural Meaning

A celebration of marital unity, prosperity, and virtuous love.

The positioning of the figures—physically close but with the woman resting her hand on the man—suggests mutual respect and emotional warmth, unusual for the time.

The cherub(s) and garden allude to fertility, Venus, or divine favor in marriage.

Portraits like this served not only to commemorate a union but to assert familial prestige and piety.

Comparative Context

Compared to Rubens’ aristocratic portraits, Jordaens’ figures appear more grounded and physically robust, more bourgeois than courtly.

Similar domestic and symbolic touches can be seen in Anthony van Dyck’s portraits, though van Dyck leans more toward idealization and grace.

The portrait also draws from genre traditions, especially Northern European ones, where symbolic objects (like gardens or animals) quietly convey meaning.

Function & Audience

Likely commissioned to commemorate a recent marriage—possibly part of a dowry arrangement or family estate decoration.

Served to represent the couple’s social status, values, and affection, possibly displayed in a private salon or gallery.

Self-Portrait with Isabella Brandt

Peter Paul Rubens

1609-10

Known as The Honeysuckle Bower

Medium

Oil on canvas (or oil on panel, depending on source)

Current Location

Alte Pinakothek, Munich

Subject Matter

Rubens and Isabella are depicted seated in a garden bower of honeysuckle, symbolizing love, fidelity, and marital harmony.

Both figures are richly dressed: Rubens in aristocratic black with a rapier (sword), and Isabella in a sumptuous red gown with delicate lace and pearls.

They sit close together, hands intertwined, a deeply personal and tender pose.

The honeysuckle bower framing them was a traditional emblem of conjugal love and faithfulness in Northern Renaissance and Baroque iconography.

Formal Analysis

Composition: Balanced and symmetrical, with the couple forming a gentle arc under the bower—suggesting unity and harmony.

Gesture: Their joined hands rest at the center of the composition, drawing attention to the marriage bond.

Clothing and Accessories:

Rubens wears a stylish wide-brimmed hat, lace collar, and a sword, emphasizing his status as a gentleman and courtier.

Isabella’s elegant attire, pose, and subtle smile project both her dignity and warmth.

Background: The lush garden and honeysuckle vines not only offer visual richness but reinforce the symbolic celebration of love.

Light & Color: Soft, warm lighting bathes the couple in a golden glow, enhancing the sense of domestic bliss. Rich, yet restrained colors reflect their noble yet intimate surroundings.

Naturalism: Both faces are carefully individualized—Rubens gives his own a slightly idealized calm, while Isabella’s expression is genuinely affectionate, with a faint, knowing smile.

Iconographic & Cultural Meaning

Portrait as Love Token: This work functions both as a marriage portrait and a personal celebration of love, companionship, and mutual respect.

The joined hands, garden setting, and intimate composition reflect themes of fidelity, fertility, and intellectual union.

The inclusion of the rapier and formal pose elevates the painting to assert Rubens’ social status—he was recently knighted and had returned to Antwerp with enhanced prestige.

Comparative Context

This portrait can be compared with Jacob Jordaens’ Portrait of a Young Married Couple for its shared emphasis on mutual affection and garden symbolism, though Rubens’ version is more polished and courtly.

Contrasts with Anthony van Dyck’s portraits, which are more idealized and aristocratic in presentation, while Rubens balances grandeur with warmth.

The pose is reminiscent of Renaissance double portraits, like those of Jan van Eyck, but with Baroque softness and vitality.

Function & Audience

Likely intended for private enjoyment, possibly hung in Rubens’ home as a personal commemoration.

It presents Rubens not just as a painter, but as a refined man of the world—a humanist, nobleman, and devoted husband.

Portrait of an Elderly (Old) Man

Jacob Jordaens

ca. 1637

Medium

Oil on canvas

Current Location

Likely housed in a European museum or private collection—this specific work is less widely circulated than Jordaens’ genre scenes, but remains representative of his portraiture from the 1630s.

Subject Matter

A three-quarter-length portrait of a bearded older man, seated or standing, rendered with intense realism and dignity.

The sitter may wear dark, formal clothing with a white collar or ruff, typical of 17th-century Flemish bourgeoisie or professional class.

His expression is thoughtful, perhaps a little weary or wise—emphasizing age, experience, and inner character over idealized beauty.

The hands (if visible) may be folded or holding an object, lending further insight into his occupation or status.

Formal Analysis

Naturalism: Jordaens excels at capturing skin texture, facial lines, and the subtle asymmetries of age—eschewing idealization for honesty and vitality.

Light & Shadow: Strong chiaroscuro gives the face volume and a sense of presence, drawing attention to the psychological realism.

Brushwork: Loose and expressive, especially in the background and fabric, but tighter and more focused around the face and hands.

Color: Muted earth tones dominate, with restrained use of color—a somber palette befitting the age and character of the sitter.

Background: Likely dark and neutral, allowing the sitter to emerge from the shadows—typical of Baroque portraiture and creating an intimate focus.

Function & Meaning

This is likely a private commission, intended to commemorate the individual and perhaps honor a life of public or professional service.

The lack of overt symbolism (compared to allegorical works) emphasizes real identity and lived experience—Jordaens’ strength.

It may convey themes of stoicism, dignity in aging, or even familial legacy, depending on whether it was meant for a family collection.

Context

Painted at a time when portraiture was rising in popularity among the merchant and middle classes in Antwerp.

Unlike the idealized elegance of van Dyck, Jordaens’ portraits speak to a more grounded and introspective aesthetic.

Comparable in spirit to Rembrandt’s portraits of elderly men and women, though Jordaens uses richer color and more robust modeling.

The King Drinks

Jacob Jordaens

ca. 1655

Medium

Oil on canvas

Current Location

Several versions exist in museums such as the Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Brussels, the Hermitage Museum, and the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lille.

Subject Matter

A raucous Twelfth Night (Epiphany) feast, where a man (the “king”) is chosen by lot and celebrated with drink and merriment.

The central figure, often an older man wearing a paper crown, raises a wine goblet high, grinning with flushed cheeks.

He’s surrounded by a crowd of revelers: musicians, children, dogs, and women laughing or joining in.

A child or servant may hold a pie or bring more wine, and animals (especially dogs or cats) add a humorous touch.

Formal Analysis

Composition: Dense and lively, with figures packed tightly, leading the viewer’s eye in a circular rhythm around the central toast.

Color: Warm, rich earth tones with brilliant touches of red, white, and gold—heightening the sense of festivity and bodily warmth.

Light: Often strong interior lighting from the left, enhancing the volumes of figures and the gleam of pewter, glass, and fabric.

Brushwork: Vigorous and increasingly expressive—Jordaens by this point favored broad, painterly strokes with great energy.

Facial Expressions & Gesture: Exaggerated, joyful, and sometimes grotesque—emphasizing the earthiness of human indulgence.

Function & Meaning

More than just a genre scene, this painting carries moral and social commentary.

May refer to the Flemish proverb “As the old sing, so pipe the young”, a frequent theme for Jordaens.

→ Adults’ behavior sets an example—here, the elders’ drinking and bawdiness may reflect generational corruption or harmless folly.Also tied to the custom of Epiphany feasts, where a commoner is crowned “king” for a day—symbolizing reversal of order and Carnivalesque license.

Context

Painted during the post-Rubens generation in Antwerp, when genre painting flourished.

Jordaens’ version of genre scenes had a moralistic but celebratory tone, different from the more restrained Dutch scenes.

Reflects Catholic Flanders’ openness to bodily expression, humor, and satire, unlike Protestant Dutch painting of the same period.

genre scene

Still lives; capture momentary appearances/ responses, Significance in the everyday.

“As the Old Sing, so the Young Pipe”

Jacob Jordaens

ca. 1640-45

Title & Proverb

"As the Old Sing, So the Young Pipe" (“Soo d’oude songen, soo pypen de jonge”)

A well-known Flemish proverb warning that children imitate adult behavior, for better or worse.

Jordaens painted several versions of this subject throughout his life.

The ca. 1640–45 version is one of the most refined, likely located in the Mauritshuis, The Hague.

Medium

Oil on canvas

Subject Matter

A domestic scene with three older adults singing boisterously—often a father, mother, and grandmother—while a group of children play pipes or flutes.

A bagpiper (often associated with crude humor) typically accompanies the group.

A parrot, often present, reinforces the theme of mimicry.

Expressions range from cheerful to exaggeratedly grotesque—conveying both humor and warning.

Formal Analysis

Composition: Triangular and tightly knit, focusing on the generational connection—elders above, children below.

Color: Warm and saturated tones—ochres, reds, browns, and glowing highlights—create a sense of intimacy and abundance.

Lighting: Caravaggisti influence with strong chiaroscuro, spotlighting key faces and gestures.

Brushwork: Fluid and confident, with attention to textures of skin, fabric, and fur.

Facial Expressions: Carefully rendered, from open mouths to furrowed brows—heightening emotional immediacy and a touch of the grotesque.

Interpretation & Moral

The proverb serves as a cautionary tale: children mimic what they see.

Jordaens doesn't lecture, but presents the scene with humor and realism, allowing viewers to reflect.

The bagpipe and parrot reinforce mimicry and folly.

The painting may critique moral decay, parenting, or simply celebrate the vitality of family life.

Cultural & Artistic Context

Part of a long Netherlandish tradition of moralizing genre scenes, going back to Bruegel.

In Catholic Flanders, such scenes could be earthy and exuberant while still moral in tone.

Contrasts with more restrained Dutch Calvinist genre scenes (e.g. Jan Steen, who painted similar themes with more irony).

Jordaens’ background in tapestry design is reflected in his attention to texture and layering.

Legacy

As the Old Sing, So the Young Pipe became one of Jordaens’ signature compositions.

It was widely copied and engraved, and its theme remains relevant: how do adults shape the young through example?

Comparison to The King Drinks

Both works explore intergenerational dynamics, festivity, and behavior.

The King Drinks emphasizes excess and revelry; As the Old Sing is more didactic and family-focused.

Both offer a blend of satire and affection, showing Jordaens’ gift for making morality deeply human and relatable.

Assumption of the Virgin

Jacob Jordaens

ca. 1655

Medium

Oil on canvas

Likely painted for an altarpiece, possibly in Antwerp or nearby.

Composition

Divided into two registers:

Lower level: Apostles and witnesses—some gesturing, others in awe—cluster around the empty tomb.

Upper level: The Virgin, in luminous robes, is lifted by angels, ascending toward Heaven, surrounded by divine radiance.

Central, vertical axis emphasizes spiritual ascension and hierarchical divine order.

Formal Elements

Color: Rich jewel tones—especially deep blues, golds, and reds—emphasize Mary's sacred status.

Light: Brilliant heavenly light highlights Mary, drawing the viewer’s eye upward in an almost cinematic burst of radiance.

Movement: Flowing drapery, swirling clouds, and gesturing figures create Baroque dynamism.

Figures: Expressive and robust—Jordaens’ figures are solid, energetic, and deeply emotional.

Brushwork: Energetic but controlled, with soft modeling that evokes Rubens’ influence.

Theological Significance

Reinforces Catholic doctrine of the Assumption, emphasized during the Counter-Reformation.

The painting acts as a visual affirmation of faith, glorifying Mary and suggesting the reward of divine grace.

Artistic Influences

Rubens: Jordaens draws on Rubens' 1626 Assumption of the Virgin (Cathedral of Antwerp), but infuses it with his own earthy strength and emotional directness.

Italian Baroque: Influence of Caravaggio and Carracci seen in dramatic light and muscular forms.

Interpretation

Jordaens' Virgin is both majestic and human—a relatable spiritual figure.

The apostles’ emotional variety—ranging from awe to confusion—invites viewer empathy and reflection.

Emphasizes the triumph of divine love, suggesting that Mary’s bodily assumption foreshadows the promise of eternal life for all believers.

Legacy

Though less famous than Rubens’ version, Jordaens’ Assumption remains a powerful example of late Baroque religious painting in Flanders.

It shows how Protestant artists in Catholic Flanders could navigate religious subjects with devotion, craft, and flair.

A synthesis of theatricality, devotion, and human warmth—hallmarks of Jordaens’ sacred works.

Calvinism

Calvinism teaches that the glory and sovereignty of God should come first in all things. Calvinism believes that only God can lead his church—in preaching, worship, and government. And Calvinism expects social change as a result of the proper teaching and discipline of the church. Jacob Jordaens converted in 1655.

Still-Life with Bouquet of Flowers

Jan Brueghel, the Elder

ca. 1607

Title

Still-Life with Bouquet of Flowers

Also known as Flowers in a Glass Vase.

Among the earliest examples of the flower still-life as an independent genre.

Not a real bouquet, but a composite of blossoms from different seasons, arranged with idealized naturalism.

Date

ca. 1607

Early in Brueghel’s mature period.

Coincides with the scientific curiosity and botanical exploration of the era.

Reflects Antwerp’s role as a hub of trade, science, and collecting.

Medium

Oil on panel or copper

Copper was often used for these paintings: allowed for extreme detail, smooth surfaces, and preservation of color.

Composition

A single glass vase, often placed on a stone ledge.

Contains a dense and diverse bouquet: tulips, roses, irises, peonies, marigolds, and more.

Often includes insects (butterflies, beetles), snails, or drops of water, heightening the sense of naturalism.

Flowers overlap, twist, and cascade, showing Brueghel’s attention to botanical structure and elegance.

Formal Elements

Color: Brilliant, varied palette—each bloom rendered in rich, luminous color.

Light: Soft, even lighting enhances surface textures and subtle shading.

Detail: Microscopic precision—each petal, stamen, and leaf is lovingly articulated.

Space: Shallow depth, focusing attention on the bouquet itself.

Brushwork: Fine, controlled—especially suited to copper support.

Symbolism and Meaning

Often read as a memento mori: beauty is fleeting, nature is impermanent.

The inclusion of insects, fallen petals, or wilting blooms reinforces this theme.

Reflects a scientific interest in flora—many flowers were rare imports from Asia or the New World.

May have functioned as a cabinet piece—artwork for private contemplation and collecting.

Context

Part of the emerging genre of flower painting in the early 17th century.

Tied to the Catholic Counter-Reformation’s celebration of natural beauty as divine creation.

Also reflects Dutch and Flemish interest in collecting, classification, and study—linked to botanical gardens and herbals.

Legacy

Jan Brueghel was a pioneer in flower still-life.

Influenced artists like Daniel Seghers, Rachel Ruysch, and Jan Davidsz de Heem.

His floral still lifes are seen as scientific, devotional, and aesthetic objects, blending art and nature with elegance.

vanitas

Genre of memento mori symbolizing the transience of life, the futility of pleasure, and the certainty of death, and thus the vanity of ambition and all worldly desires. The paintings involved still life imagery of transitory items. The genre began in the 16th century and continued into the 17th century.

Still life with Parrots

Jan Davidz de Heem

1640-45

Date

ca. 1640–1645

Created during the height of the Dutch Golden Age, when the Dutch Republic was a leader in trade, exploration, and cultural development.

The period also coincides with prosperity in the Netherlands and growing demand for luxurious and exotic items, especially from the East Indies.

Medium

Oil on canvas

Classic medium for Dutch still lifes, offering the ability to create vivid colors and textures.

Composition

The painting features a sumptuous array of objects:

Exotic fruits, such as pineapples, oranges, and pomegranates, showcasing the wealth of the era.

Colorful parrots, symbolizing luxury and the exotic.

A decorative glass vessel or bowl, often containing a flower arrangement or grapes, placed next to the fruit.

Insects (flies or bees) are occasionally included, a feature often used in still-life painting to underline the transient nature of beauty.

The parrots often serve as an exotic accent, underscoring both the artist's technical skill and the wealth generated by global trade.

Formal Elements

Color: The bright and contrasting colors of the parrots, fruits, and flowers stand out against the dark background, emphasizing the detail of each object.

Lighting: Soft, naturalistic lighting illuminates the scene, highlighting the texture of the fruits, feathers, and glass.

Texture: Masterful rendering of textures—from the glossy shine of the glass to the softness of the fruit and the delicate feathers of the parrots.

Detail: Hyper-realistic detail, especially in the depiction of the parrots’ feathers, the texture of the fruit skins, and the light reflections on the glass.

Space: The objects are tightly arranged, with overlapping elements that create a dense, rich effect.

Symbolism and Meaning

Exoticism and Wealth: The parrots and exotic fruits are symbols of the wealth and luxury of the Dutch Golden Age, where the Dutch East India Company (VOC) brought back goods from Asia and the New World.

Vanitas: The parrots’ fleeting nature and the decaying fruits can also be interpreted as a memento mori, reminding viewers of the ephemeral nature of life.

The Transience of Beauty: The insects, fading fruit, and perishable nature of the arrangement serve as a reminder that beauty and wealth are transient.

Symbol of Status: Still lifes like this were often commissioned by wealthy patrons and served as symbols of status, showcasing both the luxury and intellectual culture of the owner. They also represented the Dutch obsession with naturalism and the desire to capture the wonders of the world.

Context

During the Dutch Golden Age, the Netherlands experienced a flourishing of art, trade, and cultural exchange.

The Dutch East India Company brought exotic goods into Europe, and items like parrots became status symbols for wealthy collectors.

This period saw an explosion of still-life painting, where artists like de Heem specialized in rendering luxury objects with incredible detail.

The growing middle class in the Netherlands, with its access to trade and cultural capital, provided a steady demand for these types of works.

Still life paintings often reflected the emerging scientific interest in the natural world and the fascination with exoticism.

Legacy

Jan Davidsz de Heem is considered a master of still life and his works, such as Still Life with Parrots, are among the finest examples of the genre.

His detailed renderings of flowers, fruits, and animals influenced later artists, and he is regarded as one of the foremost Dutch Golden Age still-life painters.

The luxurious objects in his paintings serve as a celebration of the art of collecting during the period and have maintained their appeal for collectors and museum-goers alike.

Pronk stil-leven

showy still-lives

It refers to a style of still life painting popular in the 17th century Netherlands, characterized by elaborate displays of luxury goods, fruits, and other items, often arranged on a rich surface like a carpet-covered table.

fijnschilder

Translates to "fine painter" or "fine school" in Dutch. It refers to a style of painting developed in the 17th century in Leiden, Netherlands, characterized by meticulous detail, small-scale works, and a focus on creating realistic representations of everyday life. Artists like Gerrit Dou, Frans van Mieris Sr., and Adriaen van der Werff were known for their fijnschilder style.

Still-life with Poultry and Venison

Frans Snyders

1614

Date

1614

This is a typical early 17th-century Flemish still life where the Dutch and Flemish artists were mastering the depiction of realism in both the objects of nature and the symbolism tied to them.

The early 1600s in Flanders saw the rise of specialized genres such as still life, with a particular focus on the luxury market, showcasing both natural bounty and exotic trade goods.

Medium

Oil on canvas

As with many Flemish still lifes, the oil on canvas technique allowed for vivid, realistic textures—a hallmark of Snyders' work.

The medium also provided the flexibility to show complex textures like the plumpness of poultry, the gleaming surface of venison, and the tactile quality of natural elements.

Composition

The composition is bountiful and dynamic, showcasing a variety of game birds such as ducks and pheasants, as well as cuts of venison.

The game birds are often seen with their feathers arranged to show off their iridescent plumage, while the venison is often partially carved, showcasing meaty texture with juicy cuts.

The placement of the objects gives a sense of abundance—a feast for the eyes—with richly detailed foodstuffs laid out across the canvas.

There may also be hunting tools or other farming implements incorporated into the scene, subtly referring to the labor of hunting and its link to wealth and social status.

Formal Elements

Color: The composition features earthy tones that celebrate the textures of meat, feathers, and the shine of polished surfaces (such as glassware or metallic items). The warm browns and deep reds contrast against the pale skin of the poultry and venison.

Lighting: The dramatic lighting in Snyders' works highlights the textures of the meats and the sheen of feathers, making them seem almost tangible.

Detail: Incredible detail is given to every element, from the feathers of the poultry to the marbling of the venison. Snyders was a master of showing light reflection, such as how it bounces off the glistening surface of the meat.

Space: The cluttered composition creates a sense of fullness and overflowing abundance, often used in Flemish still life to underscore the theme of material wealth.

Symbolism and Meaning

Abundance and Luxury: The display of meats and poultry reflects the wealth of the owner and the growing consumer culture in the Flemish and Dutch Golden Age.

Vanitas: The scene can also be interpreted as part of the vanitas tradition, which uses the abundance of food to remind the viewer of life's fleeting nature. The display of game and meat could reflect the finiteness of pleasure and impermanence of material goods.

Symbol of Mastery: The incredibly detailed rendering of the game animals and venison demonstrates the artist’s technical mastery and could be seen as a visual representation of Snyders’ skill in capturing nature’s intricacies.

Hunting and Social Status: The venison and poultry suggest the luxury that comes from hunting, which was historically a pastime of the aristocracy. The presence of such game animals symbolizes the privileged status of those who could afford these expensive meats.

Context

During the 17th century, Flemish artists, particularly in Antwerp, developed an extraordinary mastery in painting still lifes as they capitalized on the growing market for luxury goods.

The Dutch and Flemish trade networks brought exotic and luxurious goods into Europe, contributing to an increased interest in capturing the wealth and variety of items available in this period.

The still-life genre was highly popular with wealthy patrons, who saw these works as a means of displaying both their taste and wealth.

Legacy

Frans Snyders is considered one of the foremost masters of Flemish still life and his work influenced later generations of still-life painters, including Jan Davidsz de Heem and Willem Kalf.

His dynamic and detailed animal and food depictions continue to be admired for their vivid realism and their capacity to evoke both luxury and mortality.

Snyders’ ability to render natural textures with such precision continues to be a benchmark for still-life painters even today

baroque still-lives

Popular in the 17th century, often explored the theme of vanitas, which means "the vanity of vanities." These paintings conveyed the fleeting nature of earthly pleasures and the inevitability of death, often through symbolic imagery like skulls, hourglasses, and fading flowers. They also served to demonstrate an artist's technical skill and love for detail, especially in depicting textures and light.

Bitter Drinks

Adriaen Brouwer

ca. 1630

Date

c. 1630

This piece was created during Brouwer's time in Antwerp, where he worked in the early 17th century, a period marked by the growing interest in genre painting.

Brouwer was also influenced by Dutch realism, which captured everyday life in stark detail, often emphasizing realistic and gritty depictions of ordinary people and their habits.

Medium

Oil on Panel

Brouwer typically used oil on panel for his works, which allowed him to achieve intricate detail and create lively, expressive textures in his figures and surroundings.

His style was characterized by bold brushwork and a dramatic use of light and shadow, often seen in his representations of faces and figures.

Composition

The composition of the painting focuses on a single figure, the man holding the glass of bitter drink, who occupies the foreground.

His face is typically worn, possibly reflecting the effects of alcohol consumption.

Brouwer often used expressive facial gestures to communicate the psychological state of his subjects, in this case, suggesting the unpleasant nature of the drink or the grim reality of overindulgence.

The background is typically minimal, often focusing on the immediate experience of the subject and highlighting facial expressions and gestures.

Formal Elements

Color: The palette of the painting is earthy and muted, with tones of brown, red, and yellow often dominating. This reflects the grittiness of the subject matter and the intimate, close-up nature of the scene.

Lighting: Brouwer uses strong contrasts of light and dark (chiaroscuro), bringing attention to the subject’s face and the expression of distaste as he drinks.

Brushwork: The brushwork is loose yet precise, capturing the roughness and texture of the subject’s face and hands. Brouwer’s characteristic vivid realism shines through in the facial features and emotions of his figures.

Emotion: The figure’s expression conveys a sense of discomfort or displeasure, which might be indicative of the negative effects of drinking. His emotive reaction captures the human flaws Brouwer often explored in his work.

Symbolism and Meaning

Alcoholism and Intoxication: Bitter Drink can be seen as a commentary on the dangers of overindulgence in alcohol. The unpleasant reaction of the figure suggests a warning about the consequences of such behavior.

Human Folly: Brouwer often painted people in situations of drunkenness or excess, capturing the human follies of pleasure-seeking and excess. His works often reflect moral lessons about the emptiness or unpleasantness of such indulgence.

Social Commentary: The depiction of a common person drinking suggests a critique of social behavior among the lower classes, yet it also serves as a universal reflection on human vice.

Psychological Depth: Brouwer’s skillful rendering of facial expressions and bodily gestures reveals a deep understanding of human psychology, emphasizing the emotional responses of the figure to the act of drinking.

Context

During the Dutch and Flemish Baroque period, genre painting became increasingly popular, with artists like Brouwer specializing in everyday life and depictions of ordinary people.

Brouwer was part of the tradition of artists that explored moral themes through intimate genre scenes, often exposing the less flattering aspects of society.

The 17th century also saw the rise of still-life and genre scenes in response to an increased focus on materialism, individuality, and humanism, reflecting both the richness and flaws of human life.

“rough brush” style

in art generally refers to a painting technique that uses bold, visible brushstrokes to create a textured and energetic effect, often evoking a sense of dynamism or movement. It's not directly synonymous with "baroque style," but it can be a characteristic used in baroque paintings.

This style involves using brushstrokes that are not smoothly blended or blended at all. Instead, the brushstrokes are left visible and often create a textured surface. This can be achieved by applying paint with a dry brush or using thicker, more visible strokes.

Picture Gallery of Cornelis van der Geest

Willem van Haecht

1628

Date

1628

The painting was completed during the Baroque period, a time when art collecting was highly fashionable among the European elite.

The 17th century saw the rise of private art collections as a means of displaying wealth, taste, and intellectual achievement.

This work was created when Flemish art was flourishing, influenced by both the Italian Baroque and the rise of the Dutch Golden Age, which brought a focus on realism and depictions of everyday life.

Medium

Oil on Canvas

Van Haecht, like many of his contemporaries, used oil paints to achieve fine details and rich textures in the depiction of the paintings and sculptures within the gallery.

The use of oil paint allowed van Haecht to capture the depth and luminosity of the art objects and the reflections in the glass frames.

The medium was also ideal for capturing the interior of the gallery, with the play of light and shadow creating a realistic and immersive environment.

Composition

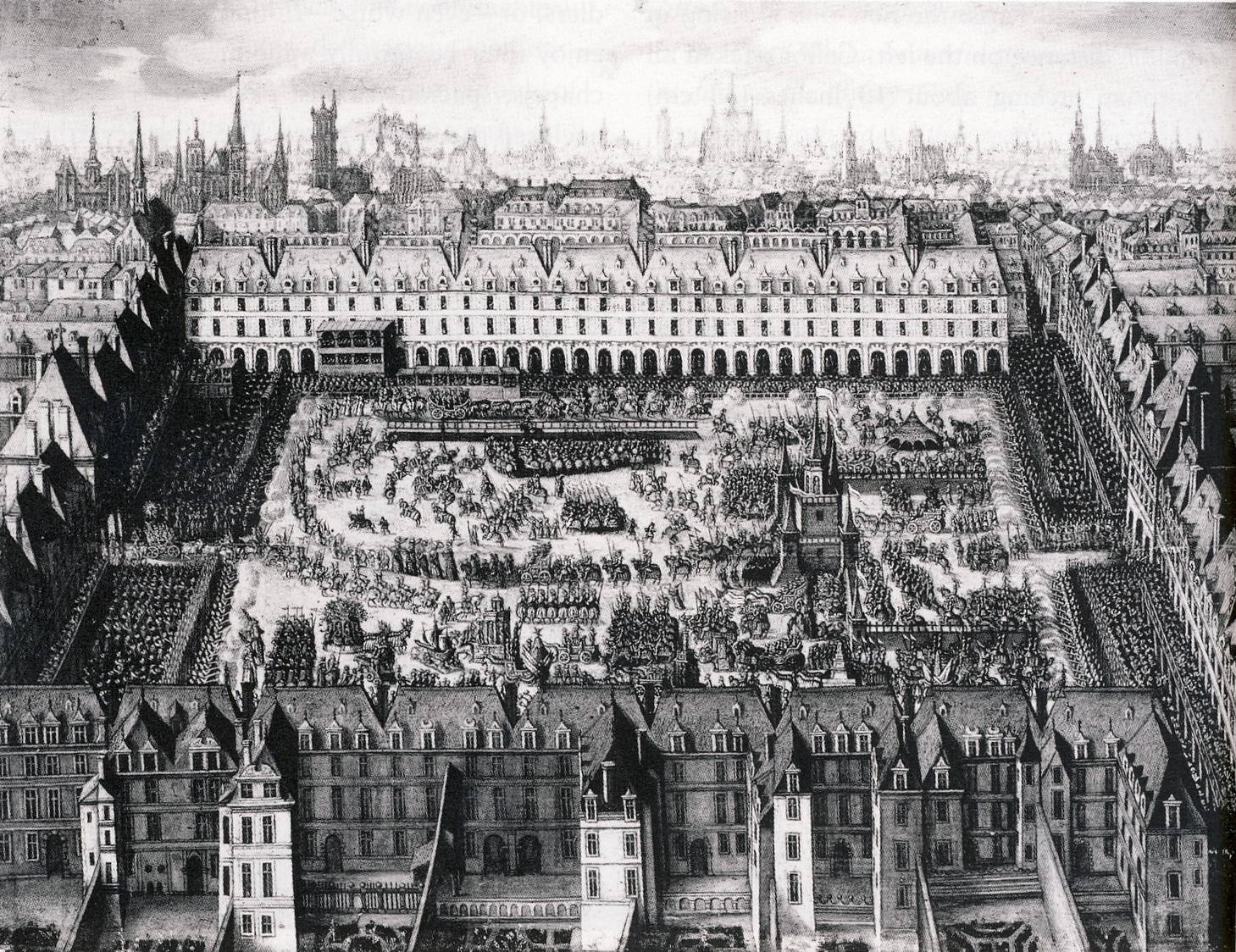

Picture Gallery of Cornelis van der Geest is a large interior scene depicting a spacious gallery filled with paintings and sculptures displayed on walls and pedestals.

In the foreground, there are figures (such as Cornelis van der Geest and his guests) admiring the art, engaging in conversations, or pointing to works that attract their attention.

The scene is carefully organized, with attention to perspective and the arrangement of the artworks. The architecture of the gallery and the space between the figures creates a sense of depth and balance.

Formal Elements

Lighting: The light is carefully controlled, with certain paintings and sculptures illuminated by natural light streaming through windows, while others are shrouded in shadow, creating a sense of mystery and depth.

Color: Van Haecht uses a rich palette of earthy tones—reds, browns, and ochres—that create a warm, inviting atmosphere. The vibrant colors of the art objects contrast with the neutral tones of the room and the figures, bringing the viewer’s attention to the paintings and sculptures on display.

Detailing: The artist’s attention to detail is evident in the intricate frames of the paintings, the reflective surfaces of the glass, and the textures of the wooden furniture and architectural elements. The realistic portrayal of the artworks on the walls serves as both an artistic statement and a tribute to the art of collecting.

Figures: The individuals in the scene are depicted with distinct expressions and postures, emphasizing their roles as collectors, viewers, or admirers of the works around them. Their gestures convey appreciation and intellectual engagement with the art.

Symbolism and Meaning

Art as a Reflection of Status: The painting depicts the high status of Cornelis van der Geest, who, like many wealthy collectors of the time, amassed a collection to show his wealth, taste, and intellectual sophistication.

The Artist's Role: The scene underscores the importance of the artist as part of the cultural elite in the 17th century. The displays of art are symbolic of the artist’s role in shaping cultural identity and preserving the intellectual achievements of society.

Art Collecting as a Moral Pursuit: During this period, art collecting was also seen as a moral endeavor that reflected patronage of the arts and cultural preservation. The careful curation of an art collection was considered a means of supporting the arts and furthering civilization.

Historical Context

The Rise of the Art Market: The early 17th century was a period of great flourishing for art markets, especially in Flanders and the Netherlands, where wealthy individuals, such as Cornelis van der Geest, began to collect paintings from well-known artists.