Social Perception + Attribution (Week 3)

1/33

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

34 Terms

What is social perception?

Social perception = “A general term for the processes by which people come to understand one another”.

Understanding arises from an interplay of 3 sources:

1. How we perceive the person

2. How we perceive the situation

3. How we perceive behaviour

A Person’s Physical Appearance

• People evaluate faces quickly, spontaneously, and unconsciously • We infer personal characteristics from the face– We read traits from faces, as well as read traits into faces, based on prior information • Superficial cues can lead us to form quick impressions

Confirmation bias

• The tendency to seek, interpret and create information that verifies existing beliefs. • This can lead to paying more attention to information about people that supports our first impressions, and overlooking contradictory information. • It can also lead to us making judgments about people based on our beliefs about the group they belong to.

Self-fulfilling prophecies

The process by which one’s expectations about a person eventually lead that person to behave in ways that confirm those expectations.

‘Pygmalion effect’ in teaching

• Teacher’s initial perceptions of their students significantly predict later student performance. • Is this an example of a self-fulfilling prophecy? Do teacher expectations influence their behaviour towards a student – thus influencing student performance? • Or are teachers just accurate judges not necessarily biased?

Target characteristics • Trait Negativity Bias

– Our impressions of people tend to be more influenced by negative information than positive information.– One negative trait may be enough to outweigh numerous positive traits.

Emotion and facial expressions

Charles Darwin (1872) “The young and the old of widely different races, both with man and animals, express the same state of mind by the same movements”. The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals.

• The bio-evolutionary perspective argues that facial expressions of emotion are instinctive and universal, being either biologically innate (as the result of nervous system arousal) or having come about through evolutionary adaptation. • Based on initial work by Charles Darwin and Guillaume Duchenne (in one of the first scientific books to contain photographs).

Are emotions innate?

• In order to explore whether facial expressions of emotions are innate, rather than culturally learned, one would need to investigate the facial expressions used by humans that had had no contact with other humans. • The Fore people of the Okapu district in Papua New Guinea were one such uncontacted people until the 1950s. • The psychologist Paul Ekman visited the Fore in 1967/68 in an effort to find an answer to the question.

Nonverbal behaviour

Behaviour that reveals a person’s feelings without words, through facial expressions, body language and vocal cues.

Kinesics

• Kinesics: body movements and gestures as NVC

• Ekman & Friesen (1969) defined five types of kinesics:

– Emblems: gestures with a direct meaning e.g. ‘thumbs up’. These are highly culturally specific: in some cultures ‘thumbs up’ is an obscene gesture!

– Illustrators: body movements (usually with the hands) that accompany, and can accentuate speech

.– Adaptors/Manipulators: hair-touching, chin-stroking etc.

– Regulators: body movements that in some way regulate the flow of conversation e.g. nodding to show you understand, raising eyebrows to indicate surprise etc.

– Affective displays: Body movements that demonstrate emotion

Oculesics

• Oculesics: The use of the eyes in non-verbal communication • Eye contact or gaze: can be reassuring, or intimidating!

• Regulation of turn taking in conversation: looking at someone is a means of saying “I expect you to speak next”

• Affiliation: in groups, exchanging eye messages can be a way of expressing mutual agreement or disagreement with another e.g. eye rolling to indicate impatience/contempt

How do you know someone’s lying to you

Widespread belief that averting one’s gaze, or not looking someone in the eye, is the surest non-verbal sign that someone is lying (Vrij, 2008). • However, studies have shown that gaze aversion is not a significant indicator of lying behaviour.

Vrij (2008) suggests 2 reasons:

1. Making and maintaining eye contact is a well-practiced method of communication and thus easy to control.

2. Gaze is related to many other factors e.g. liking, embarrassment, power, proximity etc. Ironically, the belief that gaze aversion = deception may make it easier to get away with lying, simply by maintaining eye contact.

So what are signs of deception?

• Non-verbal behaviour accompanying lying is highly variable, contextual and dependent on perspective. There is no equivalent of Pinocchio's nose.

• However, DePaulo et al.’s meta-analysis (2003) did suggest the following NVC signs were suggestive of deception under certain circumstances: – Pupil dilation– Voice pitch– Lip-pressing– Blinking (but not in face-to-face interactions)

• In general, verbal channels of communication are better indicators of deception than non-verbal channels: liars take longer to formulate answers.

• There are also individual differences: you need a baseline of someone’s normal NVC when telling the truth to spot differences when they’re lying.

Contextual factors (Consequences-plannnig-complexitity- communication skills

• Consequences: Lies which are low-stakes and have few consequences (e.g. everyday social lies) are unlikely to provoke emotional difficulty or much cognitive effort. Telling high-stakes lies could be extremely stressful.

• Planning: Liars who have had time to prepare a lie, may also have had time to prepare their self-presentation and anticipate the target’s reaction. effort to keep one’s story straight.

• Complexity: The more complex the lie, the greater the cognitive

• Communication skills: People used to self-presentation in everyday life can carry these skills over to deception: those with role-playing skills and non-verbal expressivity the most convincing (in other words, good actors!)

Attribution

The process of assigning a cause to our own behaviour and that of others.

Fritz Heider (1958) – The Psychology of interpersonal relationships

People are intuitive psychologists who construct causal theories of human behaviour.- We feel our own behaviour is motivated - In order to get through life, we develop a working understanding of why other people act the way they do.- We attribute intentions, motives and emotions to animate and inanimate figures.

Schemas

• A mental framework or body of knowledge that organises and synthesises information about something. • These help us interpret people, situations, events, roles, places etc

• Once we learn that in certain situations most people act in a specific way, we develop schemas for how we expect people to act in those situations. • Once we get to know a person, we develop schemas for how we expect them to act across situations.

Situational & dispositional factors

• Situational factors: stimuli in the environment • Dispositional factors: Individual personality characteristics.

Sometimes we attribute behaviour to external causes (situational factors) and sometimes to ‘what the person’s like’ (dispositional factors)

You arrive in the Tara building just in time for a 9am lecture. • The person going in the door in front of you doesn’t hold it for you but instead lets it slam in your face. • What’s your immediate reaction? Scenario • You may be inclined to make a dispositional attribution. • But consider:– Is the person who failed to hold the door the kind of person who normally fails to hold the door?– Or … do many (most) people fail to hold the door open when it’s 9am, and they’re trying to make a lecture?

Kelley’s covariation model of attribution

K • Harold H. Kelley (1921-2003). • Argued in his 1967 model of causal attribution that people make situational or dispositional attributions according to the covariation principle. • The covariation principle: Conditions that tend to be present when the event happens and absent when the event does not happen.

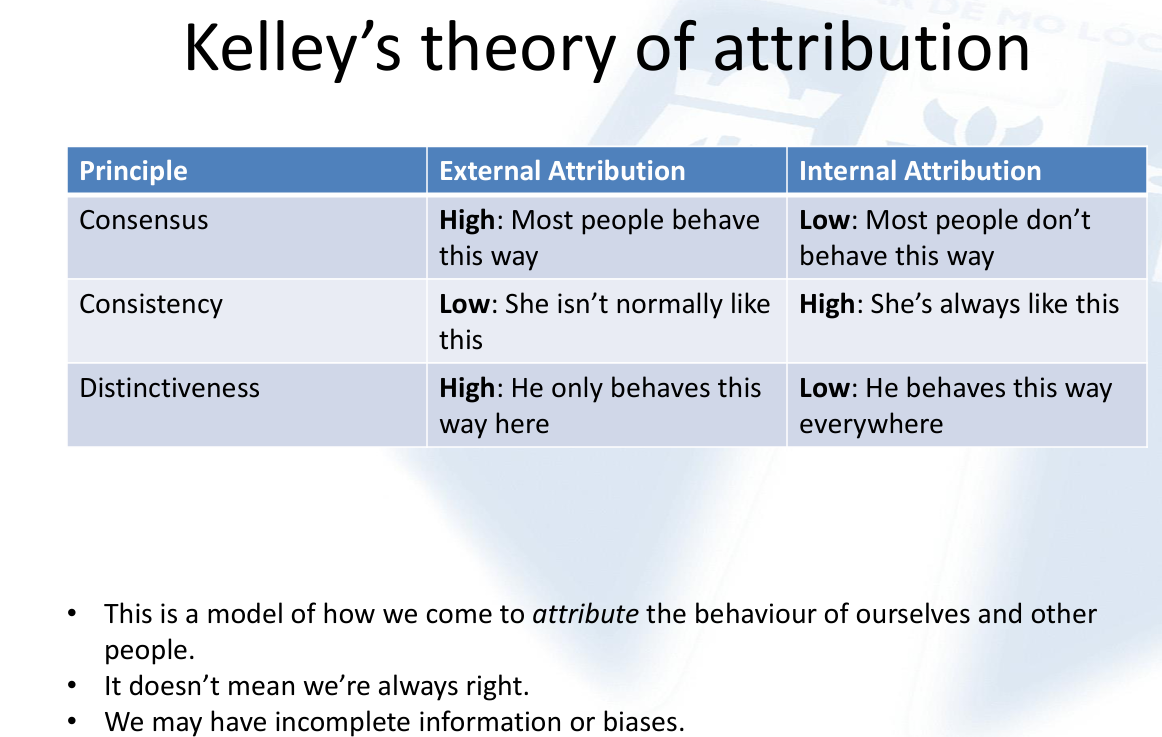

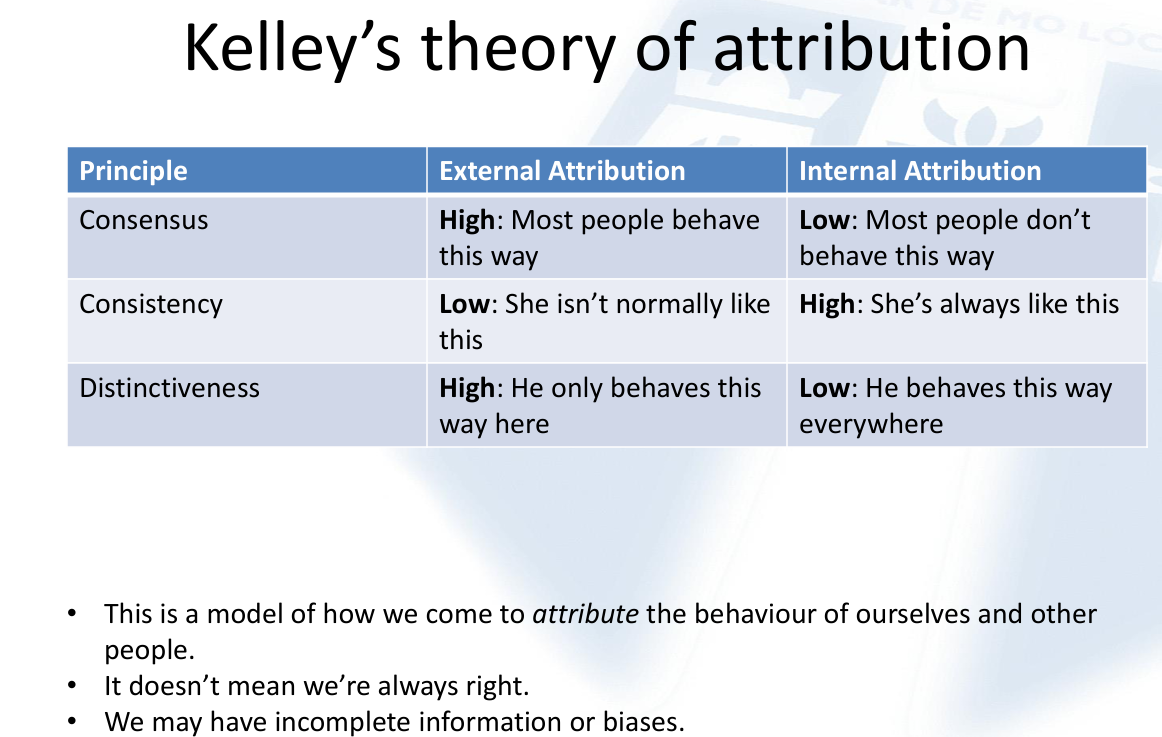

Theory of the week: Kelley’s theory of attribution

Three bases

Three bases through which we attribute a behaviour as having dispositional (internal) or situational (external) causes.

• Consensual behaviour: Would most people act like this in this situation?

• Consistency: Does this person normally act like this?

• Distinctiveness: Does this person only act like this in this particular situation?

Consensus

• If we see a behaviour, and think most people would act this way in the same situation, we make an external attribution. • If we think most people wouldn’t act this way in this situation, we make an internal attribution.

Consistency

• If we think a certain behaviour is typical of a specific individual, we make an internal attribution. • If we think a certain behaviour is atypical of a specific individual, we make an external attribution

Distinctiveness

• If we see someone behave in a specific way in one set of circumstances that is different to the way they behave in most other sets of circumstances, we make an external attribution. • If someone seems to behave in a similar specific way in most sets of circumstances, we make an internal attribution

Errors & biases in attribution

• Kelley’s theory of attribution provides us with a way of mapping how people make decisions about situational and dispositional causes of behaviour. • However, people take shortcuts, resulting in errors and bias. • We are particularly likely to do this in occasions where we are under time pressure, or where we are not motivated to think things through carefully.

Cognitive heuristics: Information-processing rules of thumb that enable us to think in ways that are quick and easy, but often lead to error.

Fundamental attribution error

• We tend to overestimate the importance of dispositional explanations rather than situational ones i.e. we tend to assume that behaviour is reflective of someone’s personality rather than the context.

• This tends to happen even in circumstances where there’s compelling evidence that something about the situation caused the behaviour.

• This appears to be an artefact of more individualist Western societies – it is not as apparent in non-Western cultures.

– Furthermore, it would appear to be learnt. Young children tend to favour situational rather than dispositional explanations.

– In other words, this is not innate. It is the result of socialisation in individualist societies.

The actor-observer effect

• We make different types of observations for our own and other’s behaviour. • In most circumstances, we are more likely to see our own behaviour as influenced by the situation, and the behaviour of others as dispositional

Self-serving bias

• We tend to attribute our successes to internal factors and our failures to external factors. • Making attributions in this way protects and maintains our self-esteem

Self-serving bias at a group level • We tend to attribute in-group failures and out-group successes to external causes such as luck. • We tend to attribute in-group success and out-group failures to internal causes such as properties of the group and their members

False consensus

• The tendency for people to overestimate the extent to which others share their opinions, attributes and behaviours. • This can lead us to make incorrect attributions based on ‘most people would behave this way in this situation’. • Likely to occur if we surround ourselves with people who behave and think in the same way we do.

Social Perception: The Bottom Line

• Dual-process theory: Two ways of forming social perceptions 1. Quickly and relatively automatically • Based on physical appearance, preconceptions, cognitive heuristics, with minimal behavioral evidence

2. Mindfully, with control situation scenario.

• Based on careful observation and logical analysis of the individual, behavior, and

• Both approaches may be subject to bias: but more likely in the first

• Experience leads to more accurate judgements.

• Seeking to control for potential biases, and being aware of situational factors informing behaviour is an important facet of critical thinking.

Attribution and relationship success

• Attributional conflict: where partners have divergent causal interpretations of behaviours and disagree over what attributions to adopt. • Happy couples tend to credit their partners with internal attributions for positive behaviours and explain away negative behaviours through external attributions. • Unhappy couples do the opposite.

Correspondent inference theory

• Under what circumstances does an expressed attitude correspond with an underlying opinion?– How do we know that someone means what they say? • Highlighted two main elements– Perceived choice– Prior probability

We are most likely to attribute an expressed statement with an underlying belief when…– The statement is unexpected/unpopular– The statement appears to have been made as a free choice.

look at quiz show experiment in week 3 tutorial.

Castro & 1960s America

• Fidel Castro: the leader of Communist Cuba • Assumed power following the 1959 Cuban Revolution • 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion • 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis • A ‘bogeyman’ for 1960s America

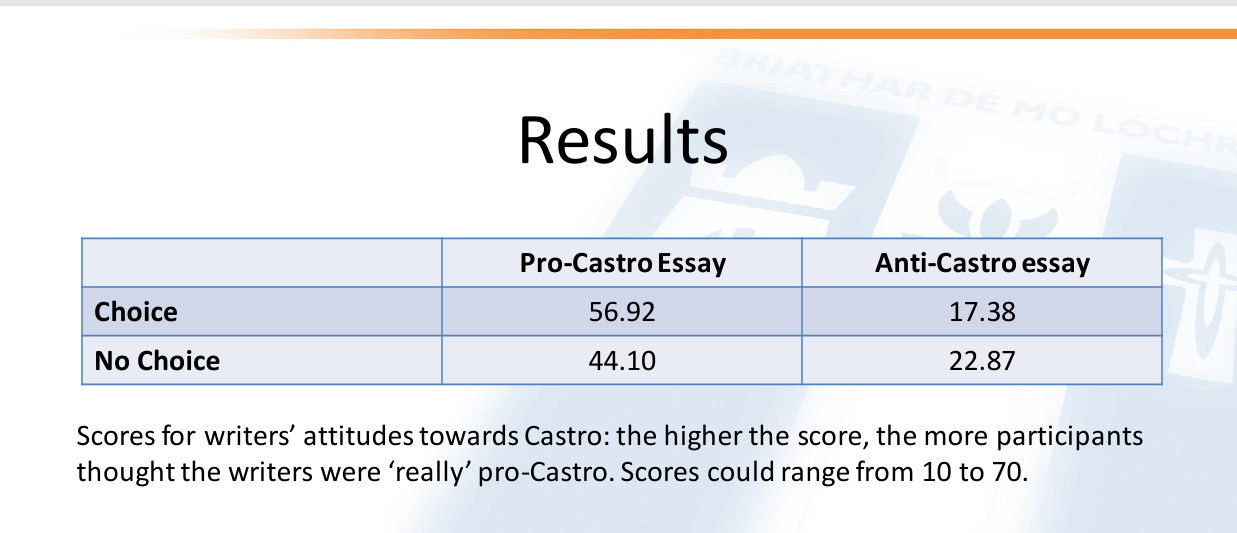

Experiment 1 • Participants (n = 51, 36 male, 15 female) were asked to read a short coursework essay on ‘Castro’s Cuba’ and record their estimates of the writer’s true attitudes towards Cuba.

• The essay was presented either as providing… a) A short criticism of Castro’s Cuba b) A short defence of Castro’s Cuba No choice c) A short essay criticising or defending Castro’s Cuba Choice

Experiment 1: variables • Independent variable 1: whether the essay participants read was pro or anti Castro • Independent variable 2: whether the essay writer had a free choice – This is known as a 2x2 factorial design

• Dependent variable: The participants’ ratings of the writer’s true attitudes towards Castro– Participants were also asked to rate their own attitudes towards Castro, and to rate various qualities of the essay writer. Essay excerpts Pro ".. . . .the people of Cuba now have a share in the government and are demonstrating their approval by their tremendous response to the trials of building a new society from the wreckage left by the exploiters of foreign industry.

" Anti "Castro can and does attempt to take over our neighbours and convert them to communist satellites by using methods of infiltration sabotage and subversion. "

Hypothesis • “When a person expresses a modal (high probability) opinion, attribution of underlying attitude will not vary as a function of perceived choice; when an unexpected or unpopular perceived.”

opinion is expressed, correspondent attribution will vary directly with the amount of choice #

• In other words, they expected:– Not to find a difference in attitude scores by choice in the anti-Castro condition

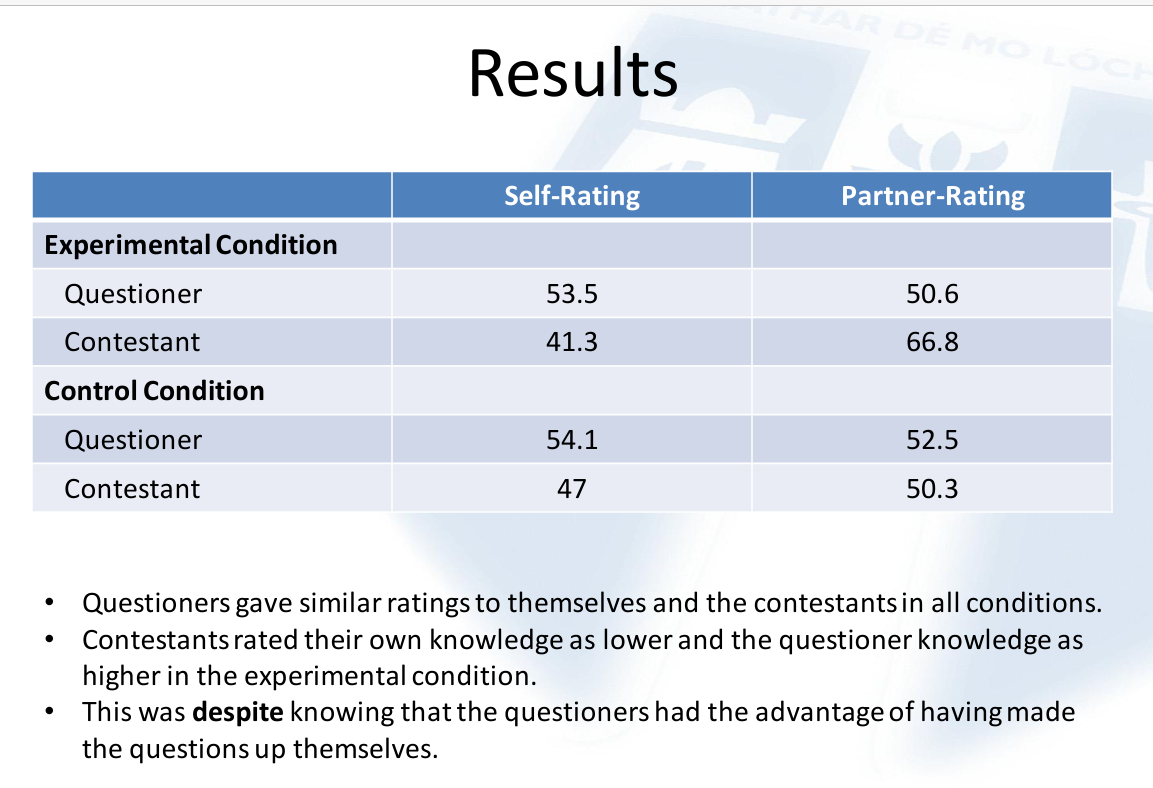

– To find a difference in attitude scores by choice in the pro-Castro condition Results Pro-Castro Essay Choice No Choice 56.92 44.10 Scores for writers’ attitudes towards Castro: the higher the score, the more participants thought the writers were ‘really’ pro-Castro. Scores could range from 10 to 70. Anti-Castro essay 17.38 22.87

• The difference between the ‘Pro-Castro choice’ and ‘Pro-Castro no choice’ was not as big as expected. • Participants gave higher ‘pro-Castro attitudes’ ratings to people who they knew didn’t have a choice in writing a pro-Castro essay, than anticipated. • Statistical tests showed this couldn’t be explained by participants own attitudes towards Castro.

• So, this required explanation and replication! Further tests found similar results – participants seemed to presume that people’s arguments reflected their ‘real’ beliefs, even when they knew they didn’t have any choice in the matter.

Conclusions • Jones & Harris (by and large) found results to support their hypothesis, but noted… “A striking feature of the results in each experiment was the powerful effect on attribution of the content of opinions expressed. While the subjects do take account of choice and prior probability, as correspondent inference theory proposes, they also give substantial weight to the intrinsic or "face value" meaning of the act itself in their attributions of attitude. This is true even when the act occurs in a no choice context.” They then suggested more research on this unusual finding… Note! • Jones & Harris do not mention situational and dispositional attributions. • They also do not coin the term ‘the fundamental attribution error’. • This was done in 1977 by Lee Ross in an essay entitled “The Intuitive Psychologist and his Shortcomings”, which used the Castro study as an example. Ross, Amabile & Steinmetz (1977) • “Social Roles, Social Control, and Biases in Social-Perception Processes” • Published in Journal of Personality and Social Psychology • Specifically set out to test the following thesis: “In drawing inferences about actors, perceivers consistently fail to make adequate allowance for the biasing effects of social roles upon performance” uiz shows!

The quiz show experiment

Experiment 1 • Participants: 18 male and 18 female pairs.

• Randomly assigned to ‘questioner’ and ‘contestant’ roles

• Experimental condition: The questioner prepared 10 ‘challenging but not impossible’ questions.

• Control condition: The questioner used a set of questions prepared by someone else.

• The questioner posed the ten questions to the contestant, supplying the correct answer if they got it wrong, or failed to answer after 30 seconds. • Dependent variable: Both the questioner and the contestant rated their own, and the other person’s general knowledge

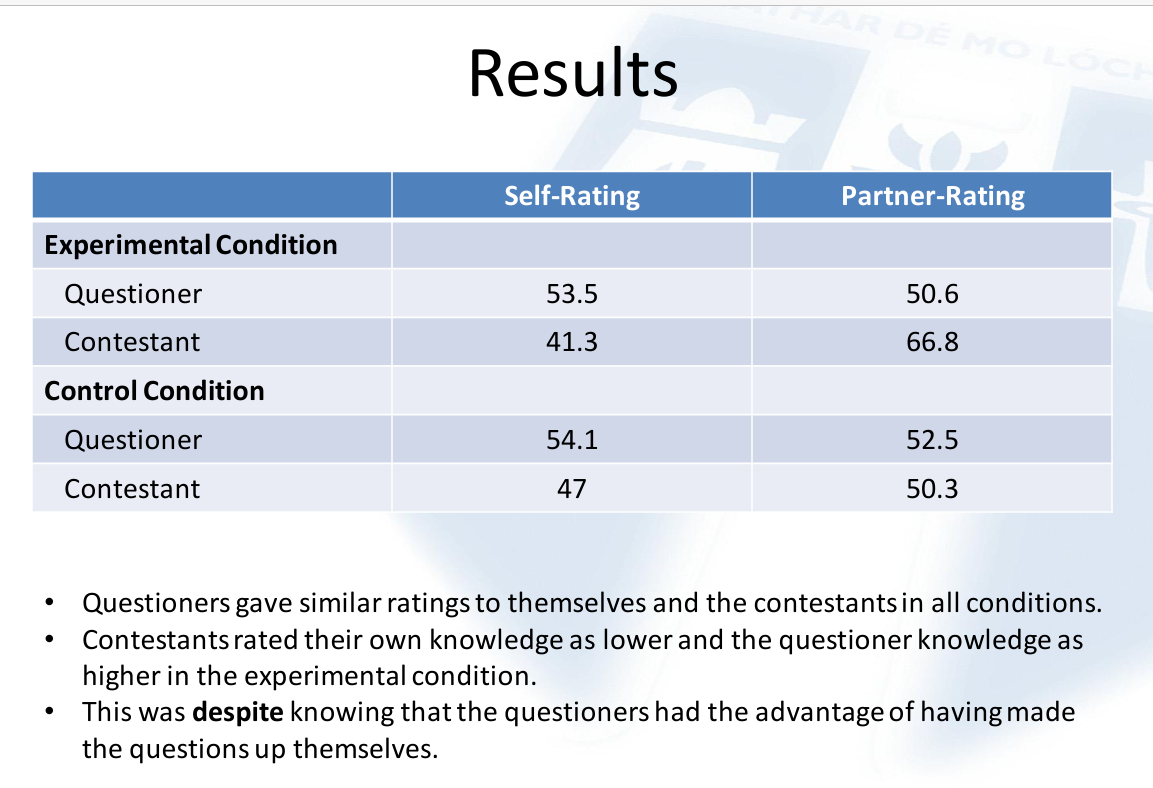

Results

Questioners gave similar ratings to themselves and the contestants in all conditions. • Contestants rated their own knowledge as lower and the questioner knowledge as higher in the experimental condition. • This was despite knowing that the questioners had the advantage of having made the questions up themselves.

Experiment 2 • Replicated Experiment 1, except this time with two observers present. • 48 observers in all.

• The observers then gave their ratings of the general knowledge of questioner and contestant “compared to the average student”

Results • The observers once again rated the questioner’s general knowledge as higher, despite knowing that they had the advantage of writing the questions themselves.

• In other words, they made a dispositional attribution for the seeming skill of the questioner (“oh, he’s quite clever”) and ignored the situational factors (“he’s made up the questions himself!”)

• Presumably any of us could look clever in a quiz scenario if we had the advantage of making up the questions ourselves! But neither the contestants, nor the observers seemed to take this into account. Copyright © 2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Meaning? What the observers, like the contestants, failed to recognize was that the questioners did not possess any superiority in general knowledge—they merely had exploited the opportunity to choose the particular topics and specific items that most favorably displayed their general knowledge.

The reader may recognise that the phenomenon we have described represents a special case of a more fundamental attribution error. In everyday life…? We regularly treat actors who play intelligent or admirable characters on TV or film as being intelligent or admirable in themselves. Played a fictional President on TV. Is actually a President. In everyday life? •

We have a tendency to ‘shoot the messenger’. • We tend to see newsreaders or journalists who deliver bad news or ask questions we don’t like, as reflecting their underlying opinions/bias.

• (This is not to deny that biased reporting exists!) Now… • In your groups, begin to brainstorm some examples of the fundamental attribution error and other biases in attribution that you may have encountered. • You will need to include examples that you have come up with yourself in your wiki assignment. • Remember, the fundamental attribution error can be any scenario where we mistakenly prioritise dispositional explanations over situational ones. It doesn’t have to be about quiz shows.