Lecture 18 - Clinical Response of Normal Tissues II

1/79

Earn XP

Description and Tags

ONCOL 335. Radiobiology. University of Alberta

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

80 Terms

Why is the inherent radioresponsiveness of normal tissues difficult to measure in humans?

very few human cells lines can be grown in vitro

what types of cells could be used for a clonogenic survival assay to attempt to measure healthy cell radioresponsiveness?

fibroblasts, lymphoblasts and potentially keratinocytes

what correlation is there between the radioresistance of fibroblasts and radioresponsiveness of normal cells?

weak correlation

how do we know radioresponsiveness is host-specific?

we have evidence for similar sensitivity to the same complication in different sites of the same individual

how do the different tissue’s stem cells radiosensitivity compare?

they are all relatively in the same region with exception to bone marrow being far more sensitive to radiation

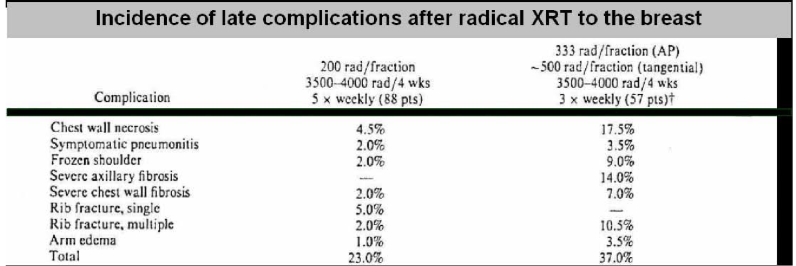

what does this research tell us?

there is clinical evidence for a difference between early and late effects in response to alteration of fraction size for the same total dose and overall treatment time

3.33/5 Gy per fraction caused significant reduction in late effects than 2 Gy fractions

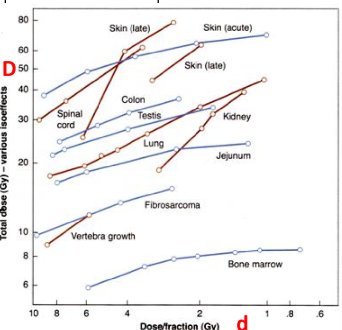

What are isoeffect curves?

plots of combinations of total dose (D) and dose per fraction to which give the same degree of tissue injury

do iso-effect curves describe late effects to have steep slopes or less-steep slopes

steeper slopes

early effects have less steep slopes

what does the increased slopes of late effects tell us in regards to fractionation

late effects are spared more by fractionation

you need a larger total dose to reach late reactions if you fractionate

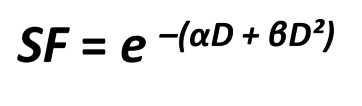

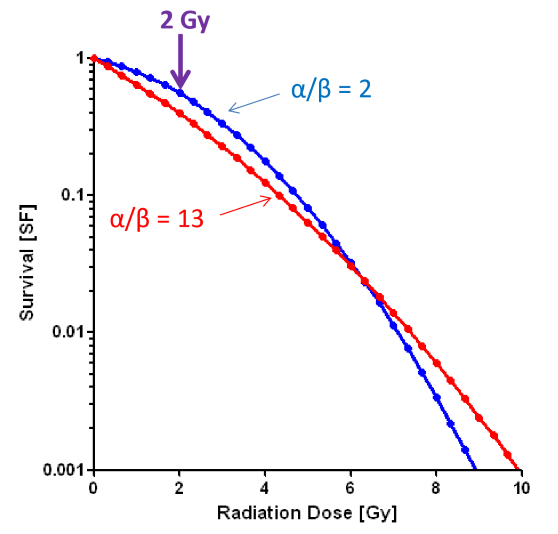

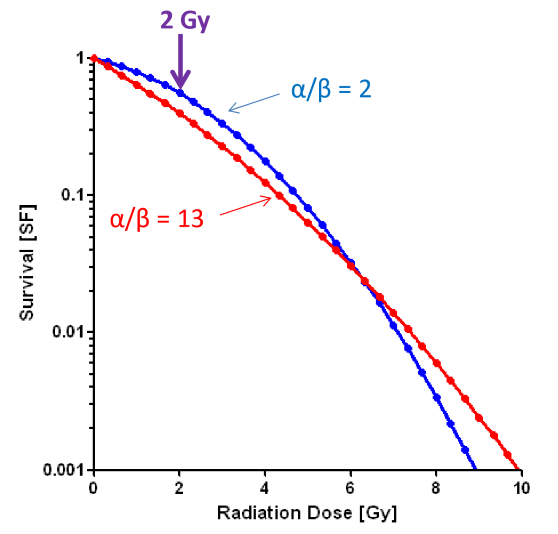

review: what are the two components of the LQ model?

alpha component of cell kill is proportional to dose

beta component of cell kill is proportion to dose²

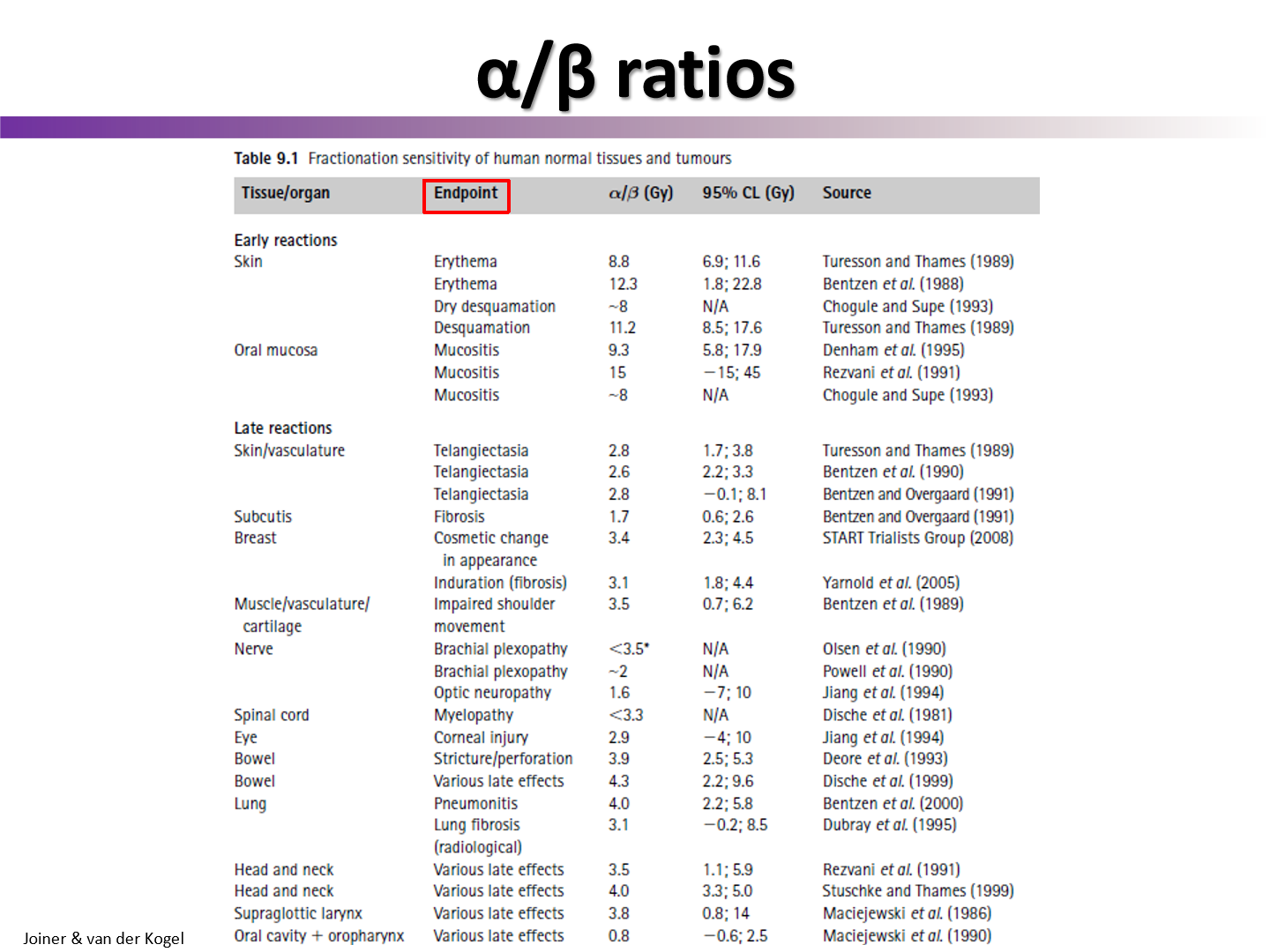

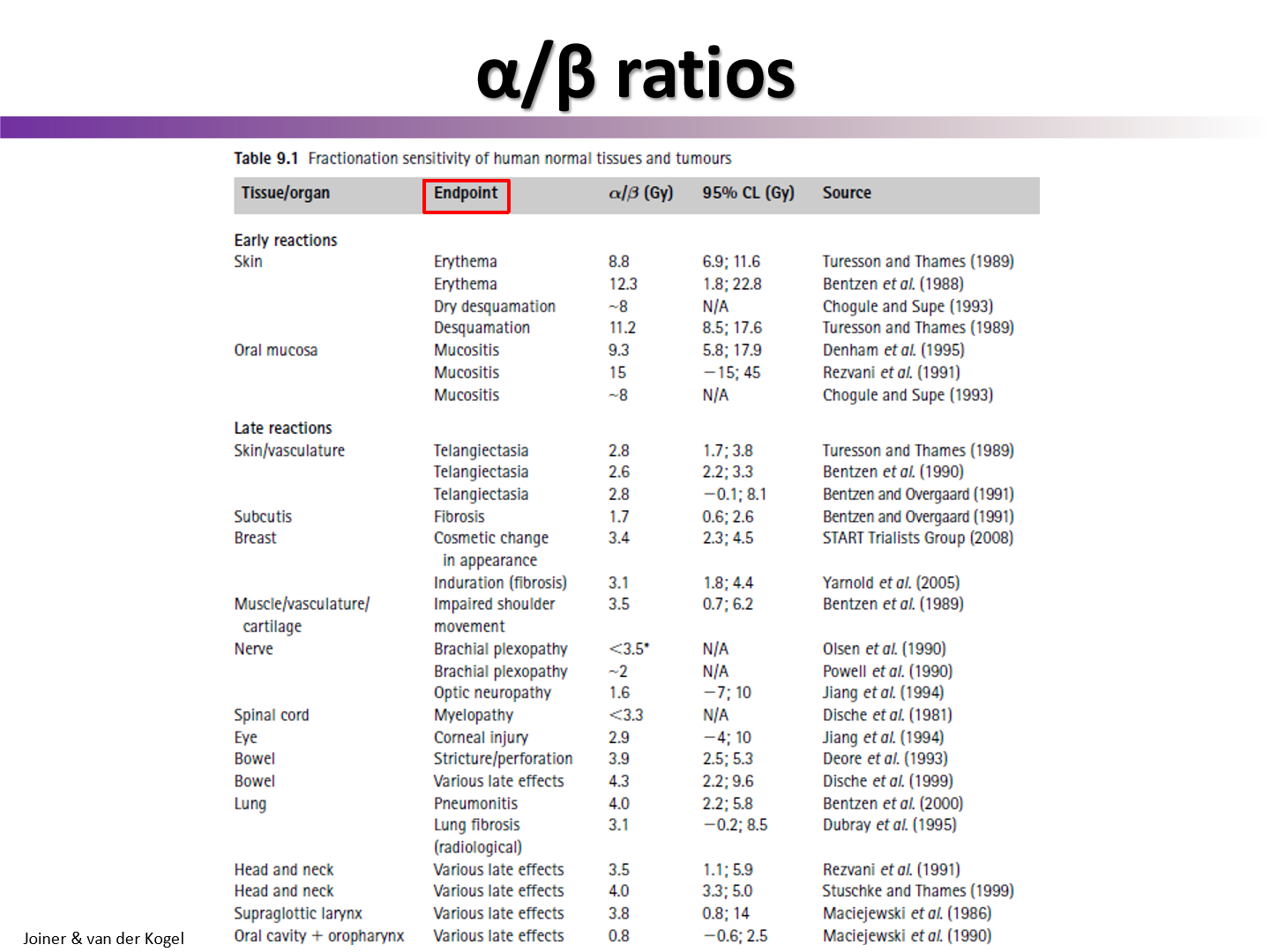

what is the alpha/beta ratio?

the dose where the linear component of kill equals the quadratic component of kill

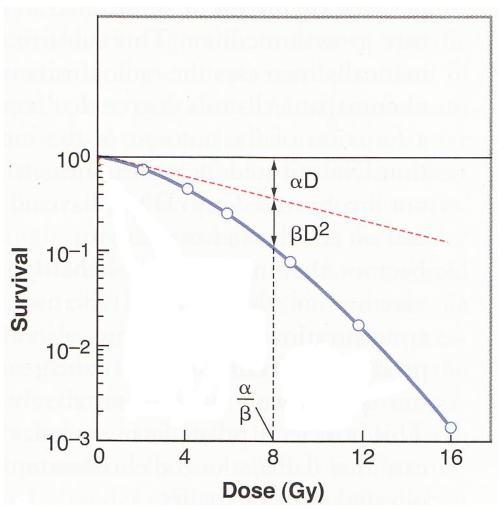

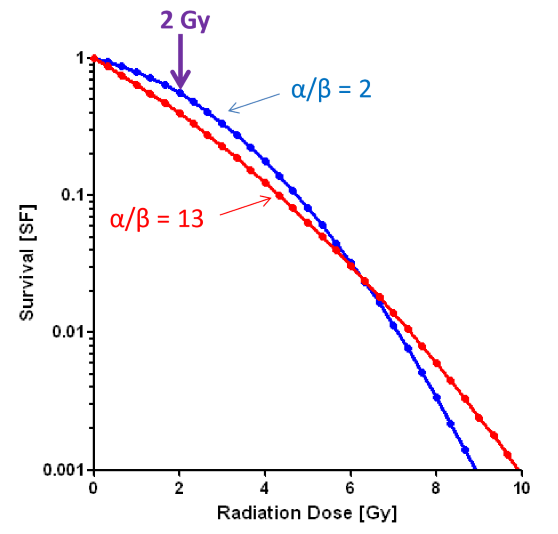

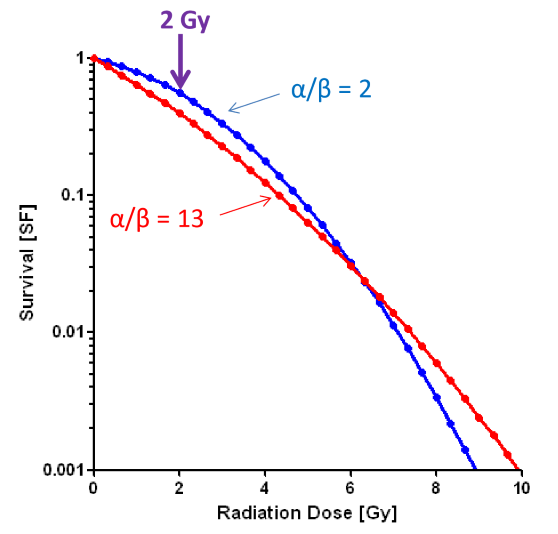

do late effects on normal healthy tissues have a high or low alpha/beta value?

normal tissues late effects typically have a low alpha/beta

do early effects on normal healthy tissues have a high or low alpha/beta value?

normal tissue early effects have a high alpha/beta

since tumors have a high alpha/beta ratio, what does this tell us about the side effects of treatment we get in healthy tissues

we will get early effects (in addition to tumor cell kill)

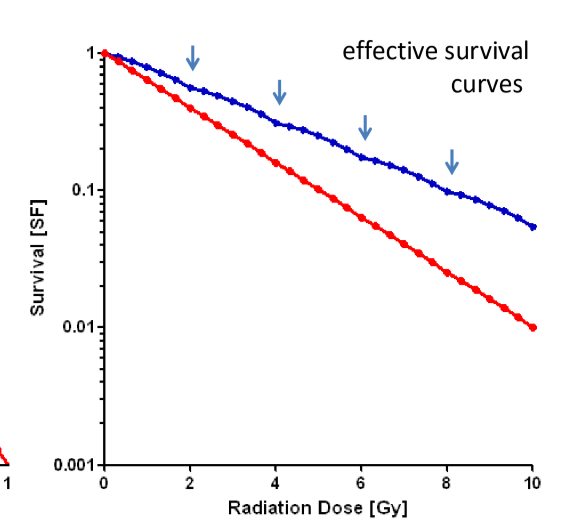

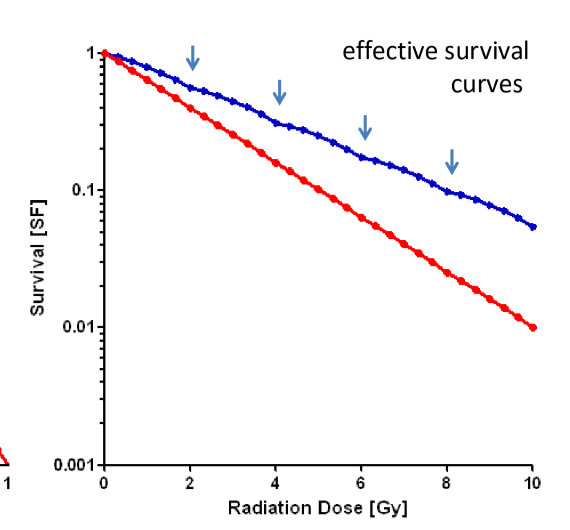

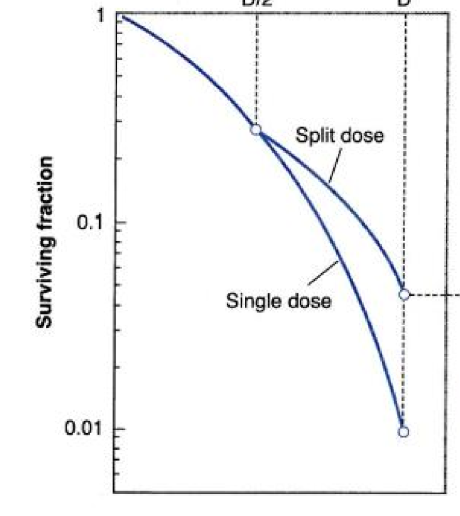

what effect does fractionation have on the LQ model?

we can now see a difference between the blue and the red line

this is evidence that fractionation will effect high alpha/beta cells (like tumors and early effects) more than low alpha/beta cells (normal tissue long term effects)

how much dose is needed for low alpha/beta cells to receive the same biological effect as high alpha/beta cells?

more dose is needed to have the SF of blue line to be equal to SF of red line

thus normal tissue is more spared with fractionation

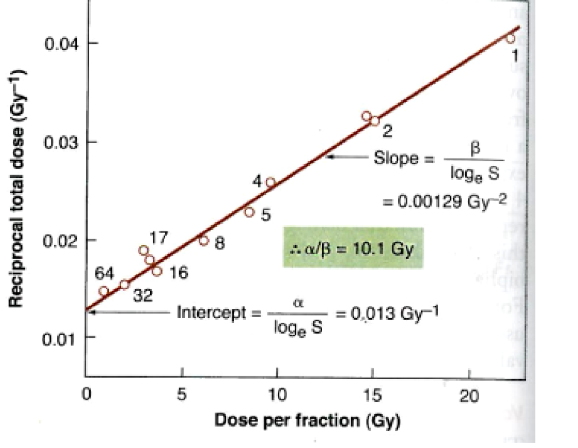

why can’t the LQ model be verified directly?

there is no single-dose survival curve data for cells that come from late-responding normal tissues

this is why single-dose survival curves are calculated using inverse process method based on fractionation data

what is the inverse process method for single dose survival curves?

we reciprocate the total dose and then find alpha/beta with information from the slope and the intercept

do early reactions have low or high alpha/beta

high

this is why we see these side effects when we fractionate

have similar alpha/beta to tumors

do late reactions have high or low alpha/beta

low

this is why we spare these effects when we fractionate

have similar alpha/beta to healthy tissue

what is the only tumor type that has a low alpha over beta

prostate cancer

since prostate cancer has a low alpha/beta, what type of fractionation plan should be used?

hypofractionation

Although not proven, what is a plausible explanation as to why there is a difference in alpha/beta ratios between late response vs. early responses (and tumor responses)?

differences in repair of potentially lethal damage between early and late responding normal tissues may be a factor

why might repair of potentially lethal damage be greater in late response normal tissues than for early response normal tissue?

in slow proliferating cells (which are typically late-responding tissues), repair of damage should continue for longer times, leading to more repair for the same amount of initial damage

potentially lethal damage definition

damage that could cause death, but is modified by post-irradiation conditions

when is potentially lethal damage repaired?

during the interval between treatment and assay

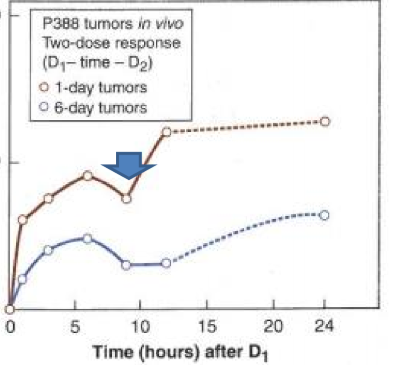

how does the repair of fast proliferating cells (high alpha/beta) compare to slow prolifereating cells (low alpha/beta)?

cells that proliferate fast will have a dip in their recovery factor since the surviving cells moved on to a more sensitive phase

slower dividing cells don’t get this dip

essentially cells resensitize if they move into a more radiosensitive part of the cell cycle

what happens to repair when we fractionate?

we get a shoulder due to the cells getting time to repair some of their damage

5 R’s of radiobiology

radiosensitivity

repair

reoxygenation

Reassortment

redistribution of cells in cell cycle

repopulation

regeneration of cells

what is another plausible explanation as to why there is a difference in alpha/beta ratios between late response vs. early responses (and tumor responses)?

tissues are heterogenous with their cells and what phase of the cell cycle they are in

typically late responding tissues will all be in one phase of the cell cycle

while early responding tissues will all be in another phase of the cell cycle

this could result in an overestimate of the a/B ratio in fractionation experiments

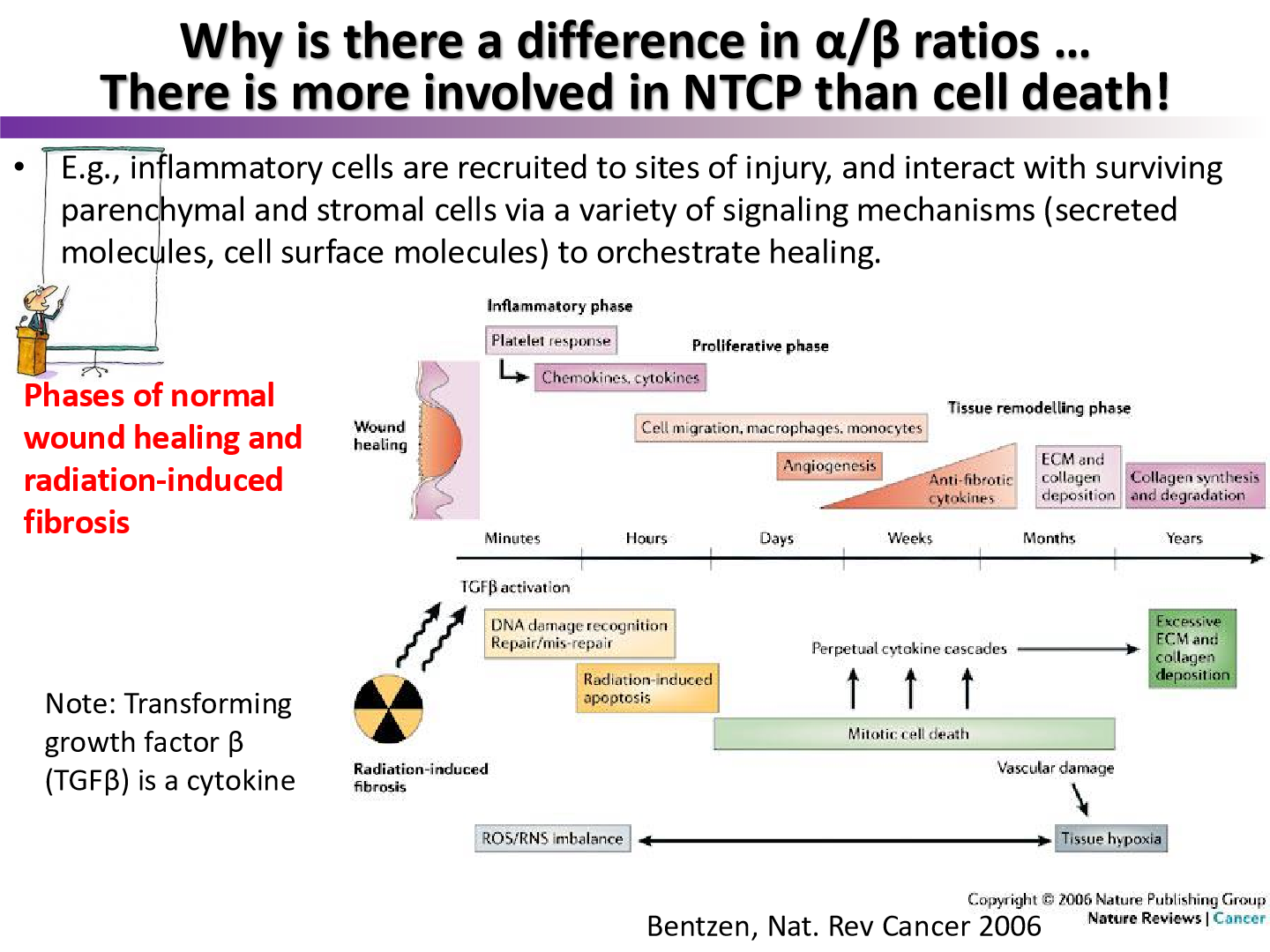

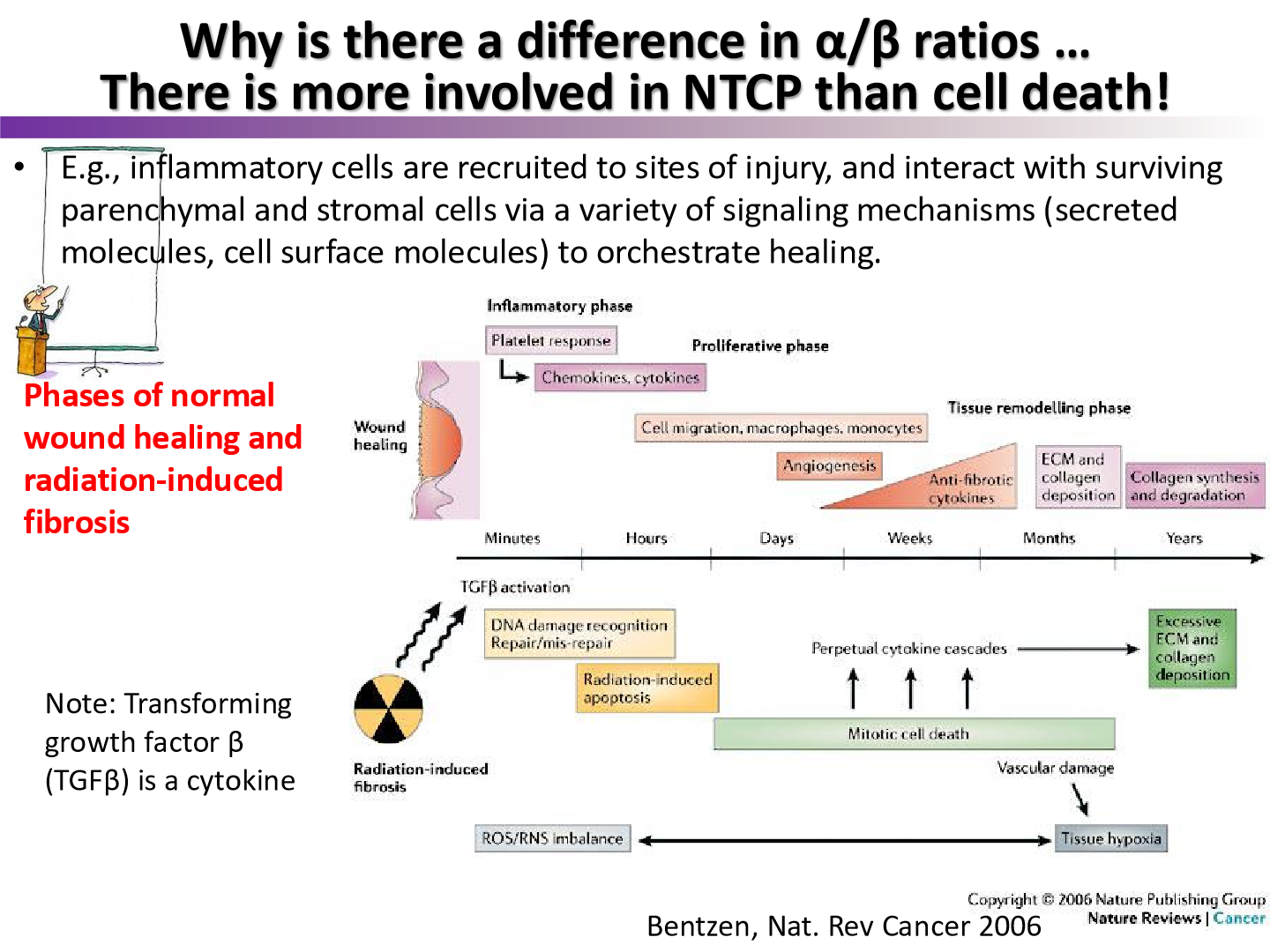

what is one more explanation as to why there is a difference in alpha/beta ratios between late response vs. early responses (and tumor responses)?

there is more involved in normal tissue complictation than cell death

ex: inflammation may play a role in cell response

what are the three explanations as to why there is a difference in alpha/beta ratios in late response and early response healthy tissues?

different repair capacities of potentially lethal damage

cell cycle heterogeneity in tissues increases a/B ratio

there is more to non-tumor complications than just cell death

differences between normal wound healing and radiation induced wound

In normal wound healing we get collagen synthesis and degradation but for radiation we get collagen depostion

this decreases functionality of fibroblasts

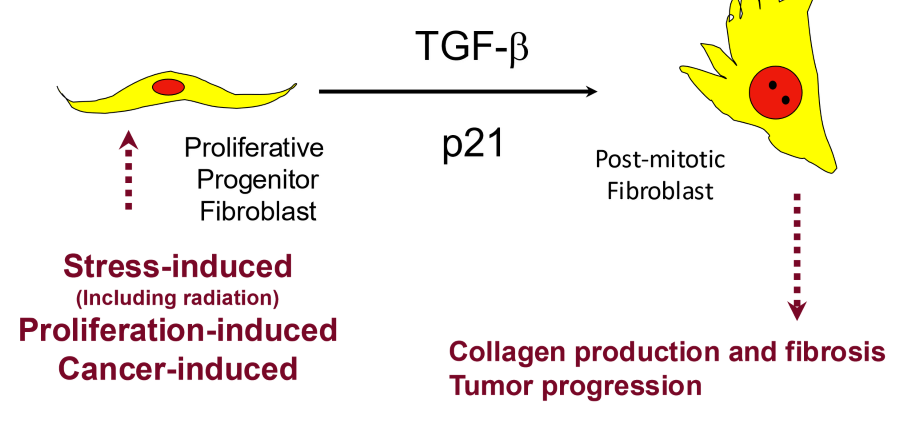

what cytokine plays an important role in radiation induced fibrosis, resulting in the difference between normal wound healing and radiation

TGF-beta

what is radiation induced fibrosis in fibroblasts?

after radiation stress, fibroblasts often go into senescence

TGF-beta upregulated = fibrosis

p21 upregulated = cell cycle inhibtion = senescence

what was the model of normal wound healing in this figure called?

the Bentzen model

what does the Bentzen model say about normal wound healing and radiation wound healing

normal wound healing is precisely orchestrated

radiation wound healing has distinct processes that may interfere with normal control of wound healing

according to the Bentzen model, what distinct processes occur in radiation wounds?

excessive deposition of ECM and collagen which lead to radiation fibrosis

why is it important to consider physiological response to radiation or normal injury?

may impact how other tissues respond to injury

for example: kidney radiation may increase blood pressure via angiotensin activation

increased blood pressure effects how other tissues react to injury

what type of exposure are most of the experiments discussed up to this point deal with

total body exposure

we have usually irradiated complete organ of mouse or complete tissue

what does the volume effect attempt to answer

what happens when only part of an organ/tissue is irradiated, and not the entire structure

what plays a big roll in the volume effect?

tissue architecture

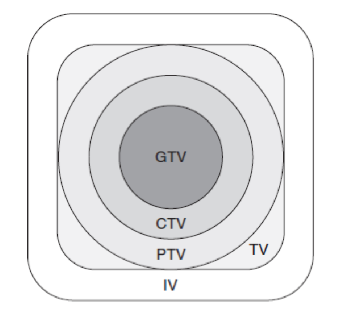

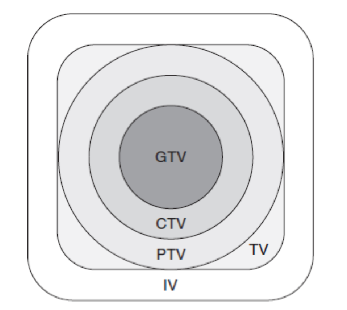

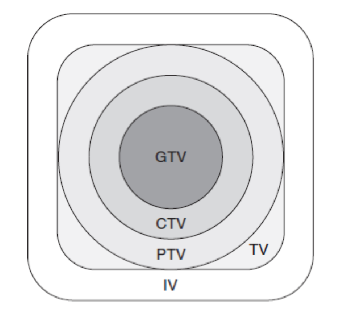

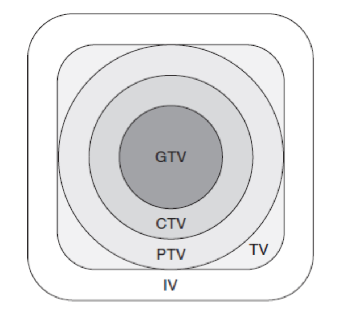

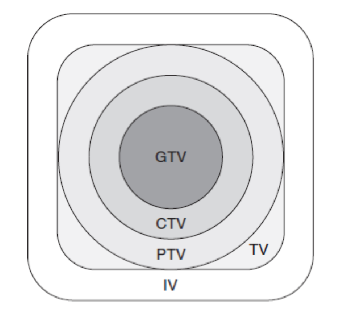

radiation volumes: GTV

gross tumor volume

CTV

clinical target volume

PTV

planning target volume

TV

treatment volume

IV

irradiated volume

what does the target/critical volume model assume tissues are composed of

functional subunits (FSUs)

within this model, what are the two types of functional subunits?

structural

functional

structural FSUs

each subunit is divided and independent

there is a physcial barrier preventing surviving cells from repopulating adjacent FSUs

examples of structural FSUs

intestinal crypts

liver lobes

nephrons of kidney

functional FSUs

the largest volume that can be repopulated by a single surviving cell

examples of Functional FSUs

spinal cord, optic nerve

how is the function of an FSU lost?

FSU must lose all of it’s subunits

crucial variables in losing FSU function

organization of FSUs (parallel or serial)

only this one is important to remember

also

number of cells per FSU

more stem cells = trickier to kill them all

number of FSUs per organ

reserve capacity of tissue

how many FSUs need to be destroyed to cause complication

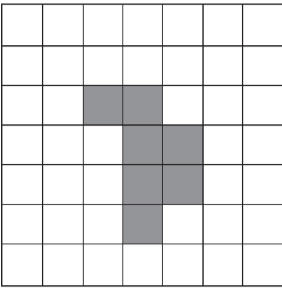

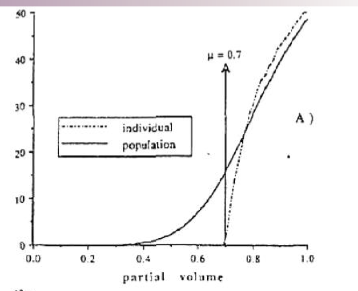

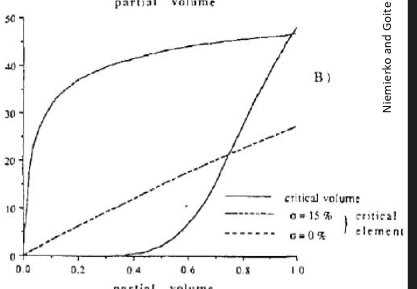

Parallel vs. serial organization of FSUs (think like circuits)

Parallel FSUs

FSUs funciton independently and organ function is sum of function of FSUs

Serial Organization

each FSU is a critical element

What causes damage in parallel FSUs

a critical number of functional subunits must be damaged before a clinical response manifests

this is called critical volume (mu)

example of critical volume (mu) for parallel FSUs

in kidney, ~90% of nephrons need to die to result in damage manifestation

therefore mu = 0.9

What causes damage in serial FSUs

failure of one FSU results in loss of function for the entire organ

one FSU is called a critical element

example of a critical element for serial FSU

damage to one lower motor neuron can cause flaccid paralysis

will serial FSU organ/tissues be more sensitive to whole organ radiation or partial organ radiation?

partial organ radiation

all we need is one FSU to be damaged to cause organ failure

will parallel FSU organs/tissues be more sensitive to whole organ radiation or partial organ radiation

whole organ radiation

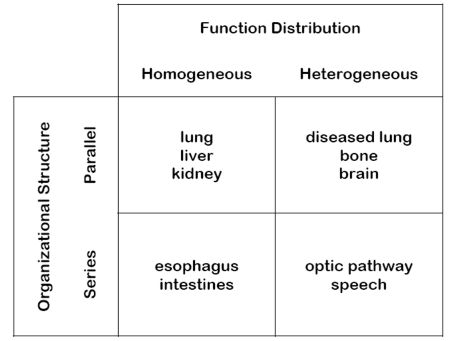

what are serial and parallel FSUs an important example of

how important tissue architecture plays a role on the critical volume theory

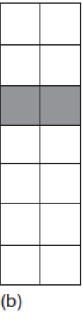

why is the curve so steep for the spinal cord graph?

due serial FSU organization

what type of curve do parallel architecture organs follow?

threshold curve

more than 70% of FSUs must be destroyed to cause complication

what type of curve do serial architecture organs follow?

linear curve

one FSU being destroyed causes complication

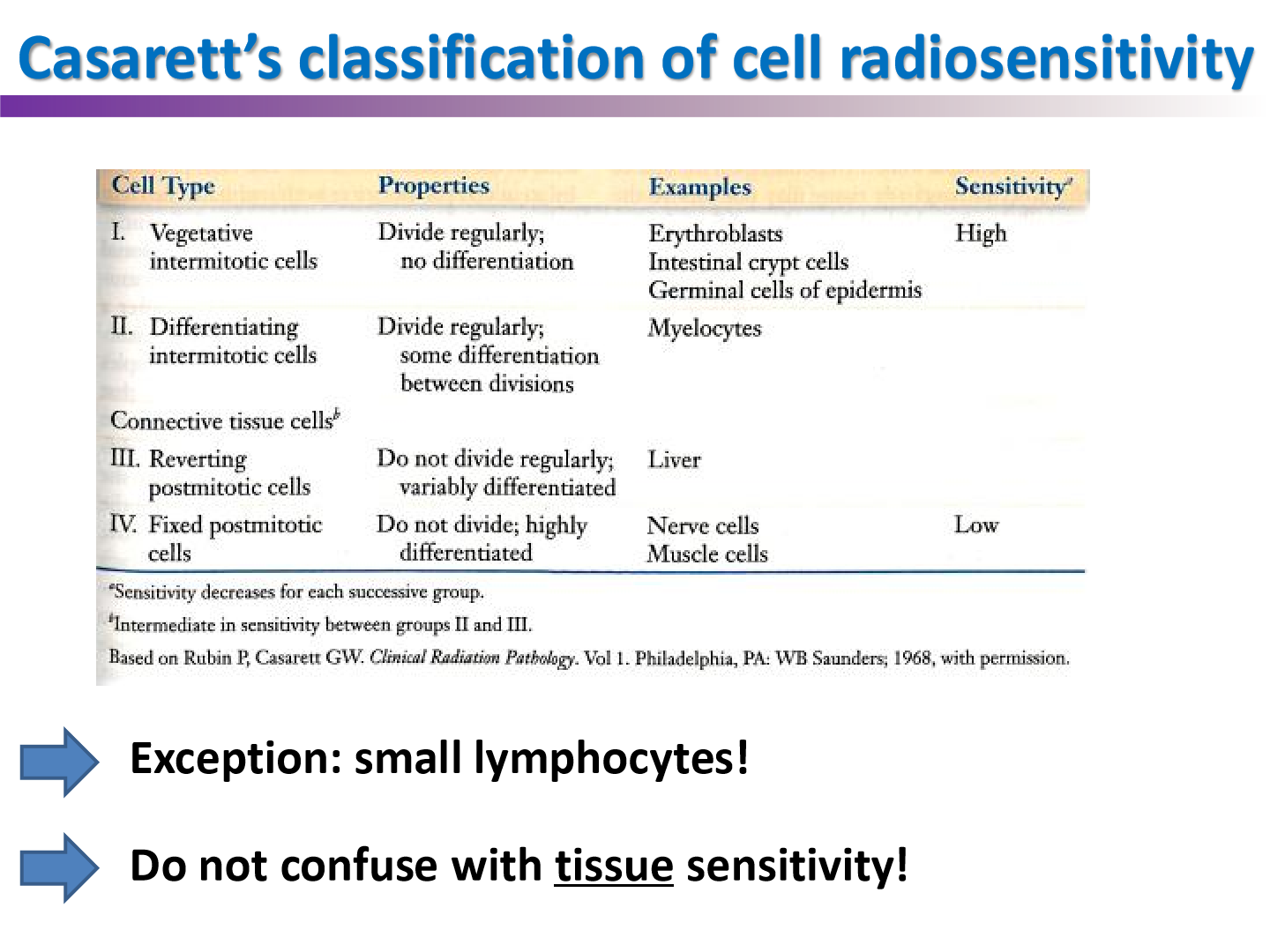

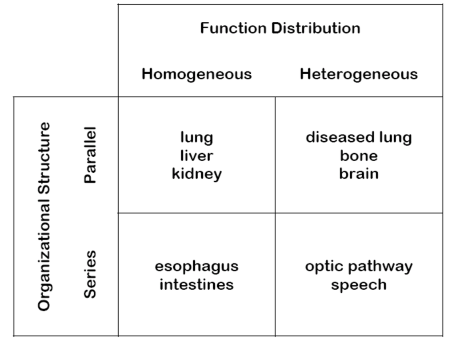

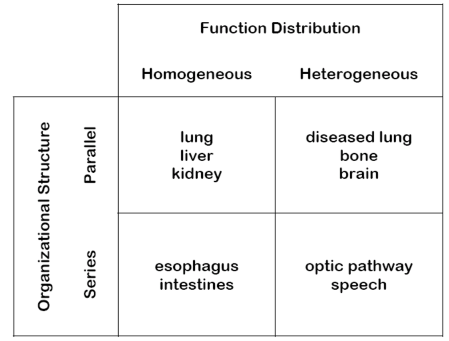

casarett’s classification of cell radiosensitivity

examples of parallel homogenous organs

lung, liver, kidney

examples of parallel heterogenous organs

disease lung, bone, brain

examples of serial homogenous tissues

esophagus, intestines

examples of serial heterogenous tissues

optic pathway, speech

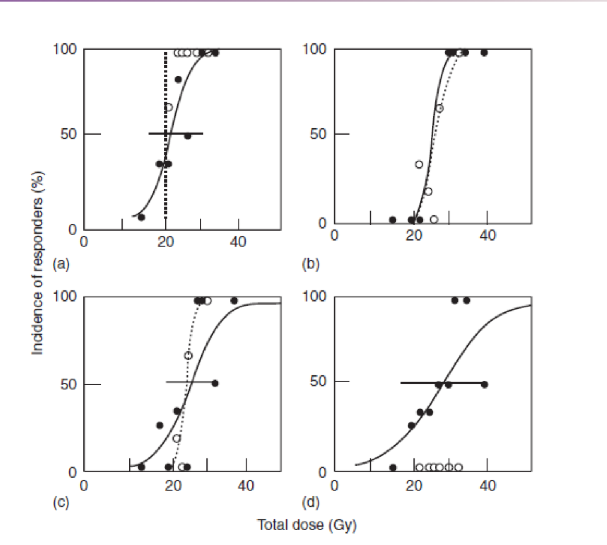

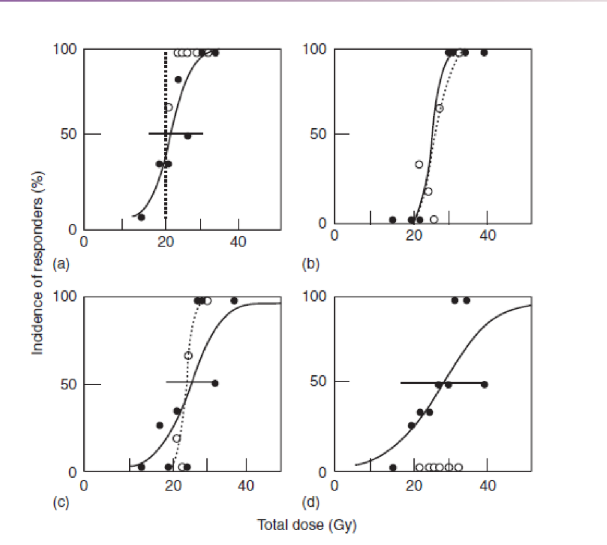

what do these graphs tell us about whole lung and half-lung irradiation

there is not much of a difference in terms of dose vs. damage ( in top row), but there is significant difference in dose vs. function

fibrosis will happen no matter how much of lung is irradiated, but decrease in tissue function only occurs if you irradiate whole lung

effect of tissue architecture 4 key points

Functional Subunit

largest tissue volume or unit of cells that can be regenerated from a single surviving clonogenic cell

if the volume of the tissue damage is less than critical damage, will complications occur in parallel organs?

no

in organs with serial organization, each FSU is _____

essential (a critical element)

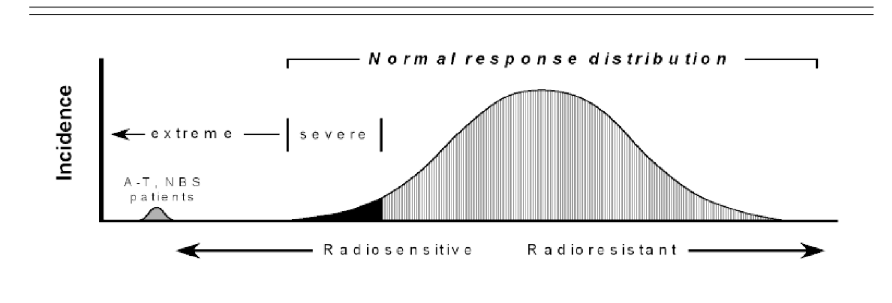

why is inter-individual variability to radiation important for the clinic

complications of radiation will vary individual to individual

people with what mutations are extremely radiosensitive?

People missing ATM or NBS genes

what assays can provide an idea of radiosensitivty for the patient (although not feasible)

clonogenic survival assays

what may be the best way to determine radiosensitivity of patients

genetic screenings to detect for certain genes that make you radiosensitive

but we don’t have too many biomarkers aside from ATM and NBS