ARKY 303 Exam 2- The Great Plains

1/33

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

34 Terms

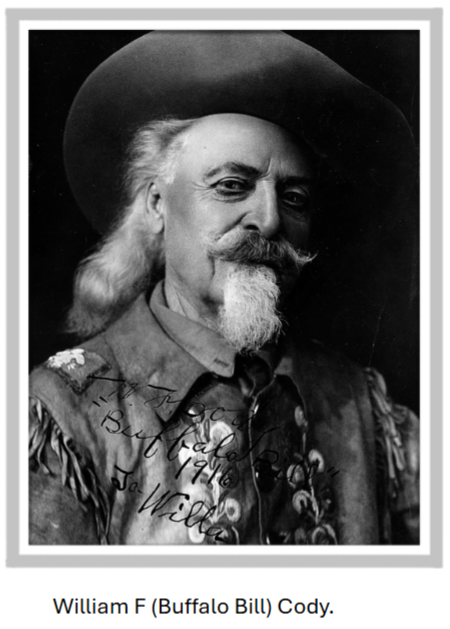

Images of Plains Indian Cultures

• Stereotypical images promoted by James Fenimore Cooper and William F (Buffalo Bill) Cody.

• Lewis Henry Morgan: Plains only occupied after the horse and rifle.

• Discovery of Folsom demonstrated long history of human occupation on the Plains

The Climate of the Plains

• Grasslands broken by islands of trees, shrubs, marshes, lakes.

• Vegetation influenced by moisture conditions.

• Harsh winters and hot, dry summers.

• Highly seasonal precipitation.

Regions within the great plains

Refer to notes and remake this card

Holocene Environmental Change

Constant shifting of vegetation and animals due to intersection of 3 major air masses.

Increasing seasonality after 9950 BP diversified plants and fauna.

Originally thought that conditions were too dry to permit human habitation on Plains.

Many climatic changes were highly localized (Bonfire Rockshelter).

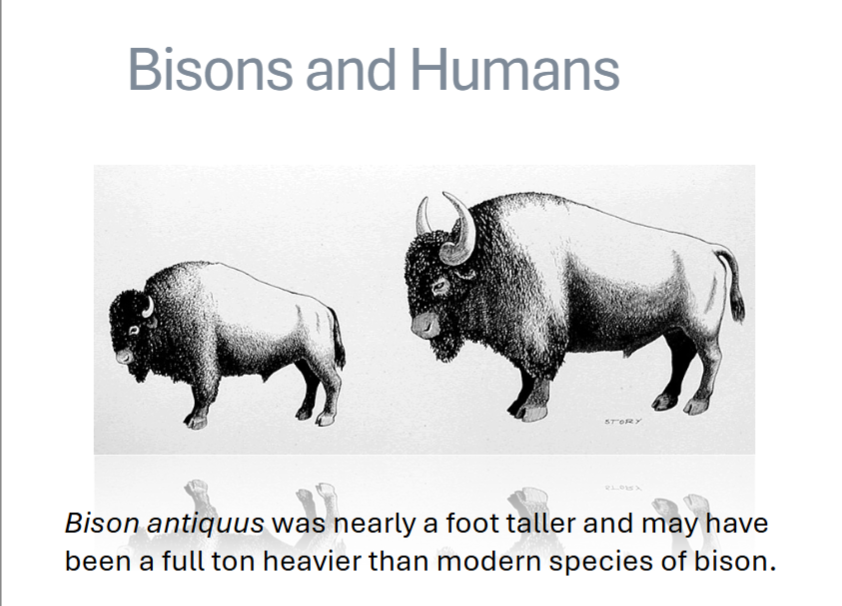

Bisons and Humans

Bison antiquus was nearly a foot taller and may have been a full ton heavier than modern species of bison

Early plains archaic (7550 BP to 1450 BP)

Archaic associated with appearance of side notched points

Increasing diversity of point forms/types through archaic period

DIversification of subsistence base

Head-Smashed-In Site and Hawken site.

Middle plains archaic c. 4800 to 2950 BP

Progressive refinement of hunting strategies and tool kits

Movement of groups onto the open plains and parkland/ boreal forest environments

The McKean complex (4900-3500 BP)

McKean gives rise to Besant and Pelican lake

Get pictures from slides and check notes on this

Middle plains archaic c. 4800 to 2950 BP (slide 2)

appearance of stone circles (tipi rings)

Can be outlines of dwellings, ceremonial lodges, monuments to dead war chiefs, or medicine wheels.

Bison hunting becomes seasonal rather than year round occurrence

Evidence for use of pounds of corrals for bison hunting (scoggin site)

Spanish entradas like desoto tried unsuccessfully to trap bison using indigenous techniques they observed

Medicine wheel flyby

Pelican Lake, Besant, & Avonlea

• Succession Model

• Overlap/interaction Model

• Technological/Style and Regionalization Model

Technology & point styles

Pelican Lake is best known for corner-notched dart points (atlatl technology), woften broad-shouldered with barbed corners.

Besant is marked by small to medium side-notched dart points with short expanding stems; also mainly dart/atlatl technology (i.e., pre-bow or overlapping with early bow adoption elsewhere).

Avonlea (later) is the classic bow-and-arrow horizon with thin, small side- notched points, generally post-dating the onset of Besant; it’s relevant because it helps bracket the tail end of Besant in some regions

Pelican Lake verses Besant

Chronology (and overlap)

• Pelican Lake generally spans the Late Middle Precontact / Late Archaic, with many syntheses placing it roughly ca. 3600–2800 BP (and in some areas extending later).

• Besant is usually placed ca. 2100–1500 BP, but evidence from the Sjovold site (Layer XIV) suggests an early Besant presence by ~2500 BP, pushing the start earlier and increasing the period of Pelican Lake–Besant overlap

Geography & raw-material networks- Pelican Lake, Besant and Avonlea

Pelican Lake and Besant both occupy wide swaths of the Northern Plains and Parklands; in many places they co-occur or stack stratigraphically, evidencing interaction or succession.

Knife River Flint (KRF) is conspicuous in many Besant/Sonota contexts, reflecting long-distance movement or exchange centered on the KRF source area in present-day North Dakota

Mortuary and “Sonota” connection

In the eastern/northeastern Plains and Middle Missouri, a mortuary expression with burial mounds is often labeled Sonota;

The Sonota complex is a mortuary and material culture manifestation closely associated with the Besant cultural tradition. It is characterized primarily by burial mounds containing bison bone offerings, Knife River Flint artifacts, and side-notched projectile points similar to Besant types. Because of these shared traits, many researchers consider Sonota a regional (or ceremonial) variant of Besant, distinguished by its mound-building practices rather than a wholly separate culture.

Subsistence & settlement

Both complexes are tied to intensive bison hunting, including communal kills and large processing locales; broad similarities make purely economic distinctions hard to sustain in many regions. Regional syntheses repeatedly note this continuity across the Pelican Lake→Besant transition

Pelican Lake- Besant relationship, 3 models

So—what’s the relationship?

Think of three partially compatible models that scholars use (often simultaneously, depending on the locality):

1) Succession model (traditional view): Pelican Lake precedes and is replaced by Besant; limited mixing occursduring the transition. This aligns with many site sequences and standard date ranges.

2) Overlap/interaction model (increasingly cited): Pelican Lake and Besant coexisted for centuries as distinct peoples, interacting within overlapping territories. The ~2500 BP Besant signal strengthens this view by lengthening the overlap window.

3) Technological/style & regionalization model: Differences (corner-notched vs side-notched) may reflect technological or stylistic choices within interacting populations, with regional expressions rather than wholly distinct “peoples.”

Late Plains Archaic in the Northwest c. 1000 BC to AD 500

• Pelican Lake (3600-3200 BP

• Besant (2500 - 1350 BP)

Pelican Lake points with wide open corner notches (1000 to 700 BC), and the later Besant Point (AD 300). Note that (Paleo-Indian) Early, (Archaic)Middle, and Late Pre-Contact

• Climax in bison hunting

• Use of arroyos, jumps, and artificial corrals (Ruby Site, Wyoming).

Ruby site in Wyoming, for example, a winged drive lane and robust corral were constructed on a low-lying stream bed along a gentle slope. Bison would’ve been stampeded along the drive land towards the corral. corral constructed of large, robust logs strong enough to resist the jostling of the frightened animals. Arky evidence suggests that rear wall of the pound was reconstructed several times - likely because it took the most stress. Many of these types of corrals were built downslope. A stout structure made from logs, and containing eight bison skulls was discovered at the Ruby site. This structure has been interpreted by George Frison as associate with Shamanism. Head Smashed In and Old Woman’s Buffalo Jump are local examples of this.

• Unequal distribution of certain cultural traits. Pottery more in eastern plains than western. Same is true for besant burial mounds- seem restricted to south and north dakota.

• High frequency of exotic items such as knife River Flint and Olivella and Dentalium shells from Pacific.

FROM HERE ON- Great plains/ plains woodland tradition

Plains woodland tradition

n many areas of North America the Woodland period is associated with the emergence of new technologies (the bow and arrow, ceramics), an increasing trend toward sedentism or semi- sedentism, and the onset of food production.

However, in many northern regions groups remained relatively mobile and continued the exploitation of animal and plant resources of the mixed Boreal forest.

The earliest archaeological manifestation of the Woodland Period in northern Manitoba is the Laurel Configuration ( 2050 BP → 1050 BP ). Use of the term “Laurel Configuration” has been suggested in recognition of variation that existswithin Laurel across areas of Manitoba, east central Saskatchewan, Wisconsin and Michigan (Lenius and Olinyk 1990:82)

Laurel Culture (2050 BP → 1050 BP).

• Toggle head harpoons; projectile points, small burial mounds, burial bundles, native copper use; hafted beaver incisors.

- Lee Syms (1977) defines Laurel assemblages as being comprised of the following traits:

• toggle head harpoons,

• overlapping projectile point typologies,

• small burial mounds with bundle burials,

• variety of stemmed and side notched projectile points,

• cold hammering of native copper into simple tools, hafted beaver incisors.

- Burial mounds are common in the southern portions of the boreal forest and copper is most common in the eastern sites around the Great Lakes

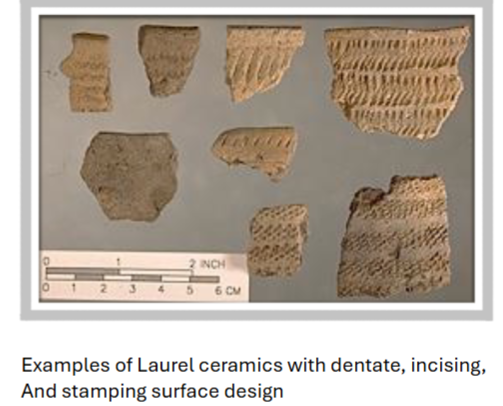

• Sub-conical and conical shaped ceramic vessels made using coil method, with non thickened lips.

plain surface finish and decorations aplies w/ wide tech range including dentate, incising, pseudo-scallop shell, push-pull, boss and/ or boss punctate, and linear stamping

Laurel configuration in manitoba conservatively dates to between 50 B.C and A.D 1000, although Reid and Rjnovich recently suggested extending laurel into 13th c. AD

Laurel Culture (200 BC – AD 900)

Semi-sedentary residence and the use of aquatic and terrestrial resources

Large summer fishing aggregations- reflected in lakeside/ riverside site locations as well as recovery of bone harpoon heads from laurel sites.

Movement between parkland and forest environments

-Scott Hamilton, of Lakehead University, has outlined three different subsistence economies considered followed by Laurel peoples:

1) large summer aggregates exploiting fish resources and small winter groups relying on scattered large mammal resources;

2) movement between parkland and forest environments exploiting seasonally available resources;

3) a strategy relying on diffuse resources in eastern and northern Manitoba and Northwestern Ontario.

Reliance on wide range of ressources

Increasing regionalization in later Laurel times (e.g.. Hungry hall phase and smith phase).

At about AD 750, regionalism begins to develop in Laurel pottery styles - probably a result of the difficulty of maintaining contact across huge areas of the boreal forest.

To the south in Northern Minnesota and adjacent Ontario, for example, two late Laurel phases emerge: Hungry Hall and the Smith Phase - both of which are characterized by elevated levels of Laurel Dentate and Punctate types.

Cultural Interaction during Laurel Times.

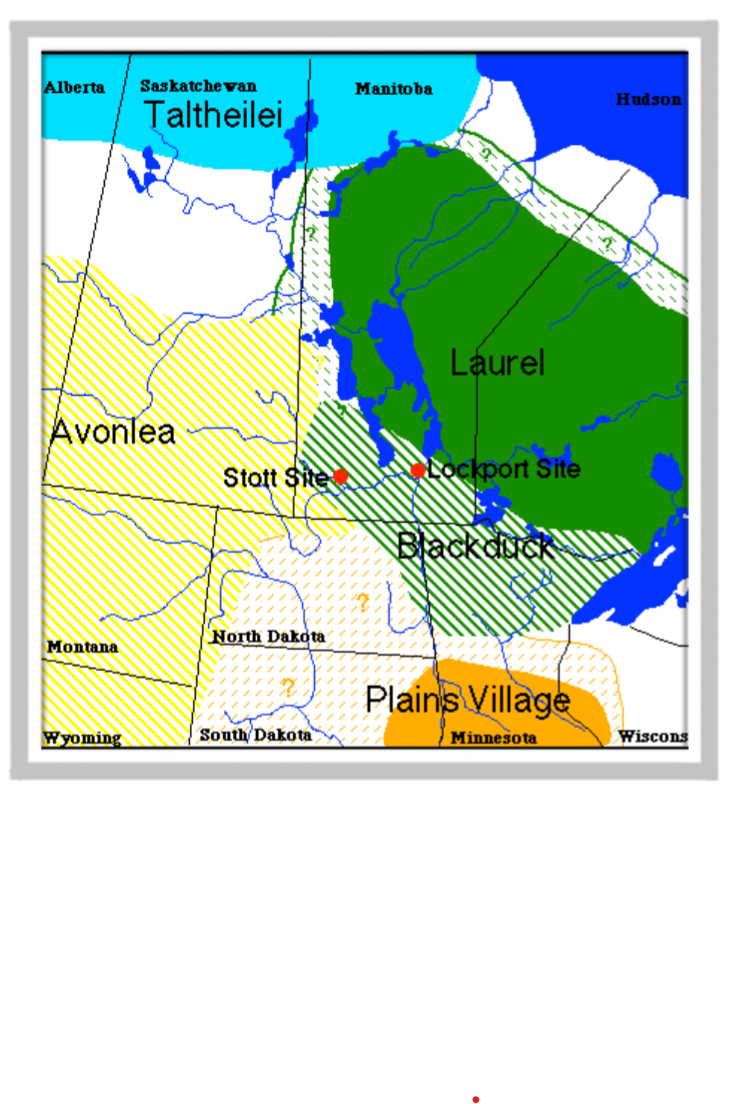

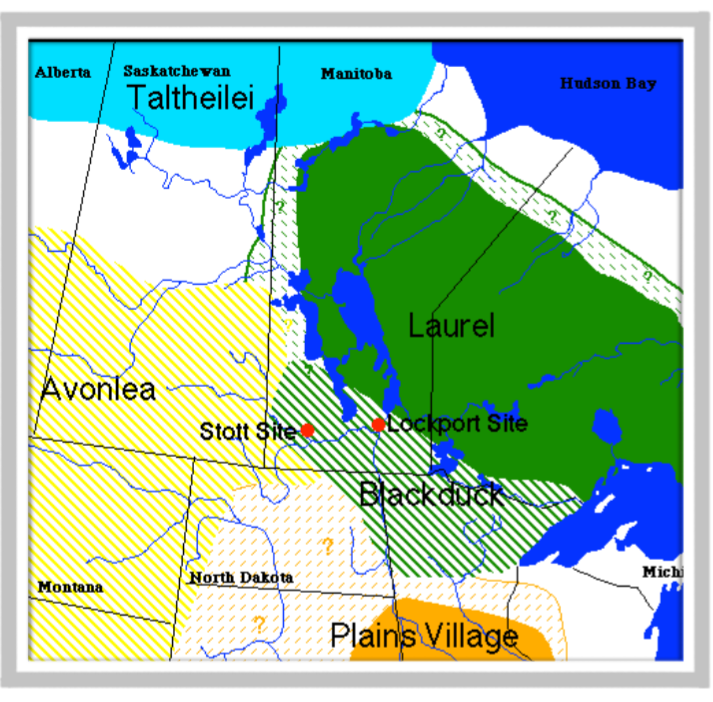

• Interactions occurred between grassland Bison hunters (Avonlea) and forest dwelling Laurel groups.

• These interactions occurred in the Parkland zone, transition between grassland and boreal forest.

recovery of laurel materials in parkland suggests that if given opportunity laurel peoples would leave forest to pursue parkland ressources

• Evidence for interaction seen in recovery of net-impressed Avonlea pottery at Laurel sites. (ex; Lockport site in Selkirk, Manitoba).

Evidence of contact only found at edge of Laurel “world”; Avonlea never found deep in boreal forest.

Similarly, in southwestern Manitoba and Saskatchewan Laurel vessels are rare or unknown beyond the forest fringe.

Patterns of interaction between grassland and parkland environments of Sask. and SW Man. indicate 3 ethnic groups: laurel, besant, and avonlea

• Little evidence for interaction between Besant and both Avonlea and Laurel*

a bit of interaction appears to have occured between avonlea and laurel

suggest that avonlea and besant parkland dwellers did not allow movement of laurel peoples onto their bison ranges

Plains Cultures of the Woodland Period

• Old Woman’s

• Mortlach

• One Gun

• Black Duck,

• Arvilla,

• Plains Village

• Psinomani

The Plains Woodland Period follows the Archaic and is a time of cultural diversity and increasing contacts with groups in other regions of NorthAmerica.

The most important characteristic of the latter part of Plains Woodland Period is the number of archaeologically distinct Indigenous groups on the prairies and their high degree of representation in the artifact record.

The literature documents numerous Plains cultural groups such as "Old Women's", "Mortlach", "One Gun", "Blackduck", "Arvilla","Plains Village", "Psinomani" and others. Each of these is represented in thearchaeological record primarily by distinctive ceramic styles, but also through faunal remains, projectile points, and associated settlement patterns and burial practices.

The sheer number of Terminal Woodland sites compared to earlier Archaic or Initial Woodland examples is due in part to population growth. However, to some degree, archaeological remains from this time are better represented because are better preserved than those from the earlier Woodland, Archaic or Paleo periods

The Black Duck Complex (AD 700 – 1100)

Found across the boreal forest, aspen parkland, and eastern margin of the Plains.

- laurel peoples forest dwellers who also practices wild roce harvesting/ seeding, black duck however represents a movement from the forests out into the grasslands and a use of bison hunting

Origins seem to lie in Laurel culture, but this has been disputed*.

- First appears in northern minnesota and then expands northward into ontario and southeastern manitoba, perhaps at expense of laurel peoples.

Diagnostic items include: thick lipped globular pottery; notched and unnotched points, unilaterally barbed harpoon heads; copper beads and awls, and burial mounds containing seated burials

- blackduck vessels typically globular in shape with relatively thick lips. Surface deco usually include cord wrapped surface impressions used in combination w/ circular punctates or exterior boss decoration.

In southern Manitoba, evidence from the Lockport site indicates that Laurel had ended by AD 800, replaced by Blackduck culture expanding westward across the plains of southern Manitoba. To the north (Manitoba and Ontario), it would appear as though Laurel culture persisted at least until AD.1100.

Cultural Interaction during Black Duck times

• Evidence for cultural interactions between grassland/parkland/boreal forest groups.

• At the Stott site, Black Duck ceramics mixed with late side- notched point styles and bison remains.

• Nicholson takes this as evidence for contact and social exchange between forest and plains peoples.

As w. laurel/ besant/ avonlea theres arky evidence for cultural interactions between grassland/parkland/boreal forest groups during blackduck times. Perhaps the strongest evidence for this comes from the Stott Site in southwestern Manitoba, where a mixed assemblage of debris associated with Plains and Forest cultures has beenrecorded.

The Stott site is located along several valley terraces along the Assiniboine river in the Aspen/Parkland zone, near present dayBrandon, Manitoba.

Here, Blackduck ceramics are mixed with late side-notched point styles, and a faunal assemblage dominated by the remains of bison.

Bev Nicholson has taken this to mean contact and social exchange between peoples of the forest and peoples of the plains. However, it may also represent a movement of forest dwelling peoples (Laurel) out onto the Plains, where the are transformed into Black Duck through these interactions.

Interesting also is the use of Knife River Flint from the western Dakotas - further evidence of interregional contact with other areas.

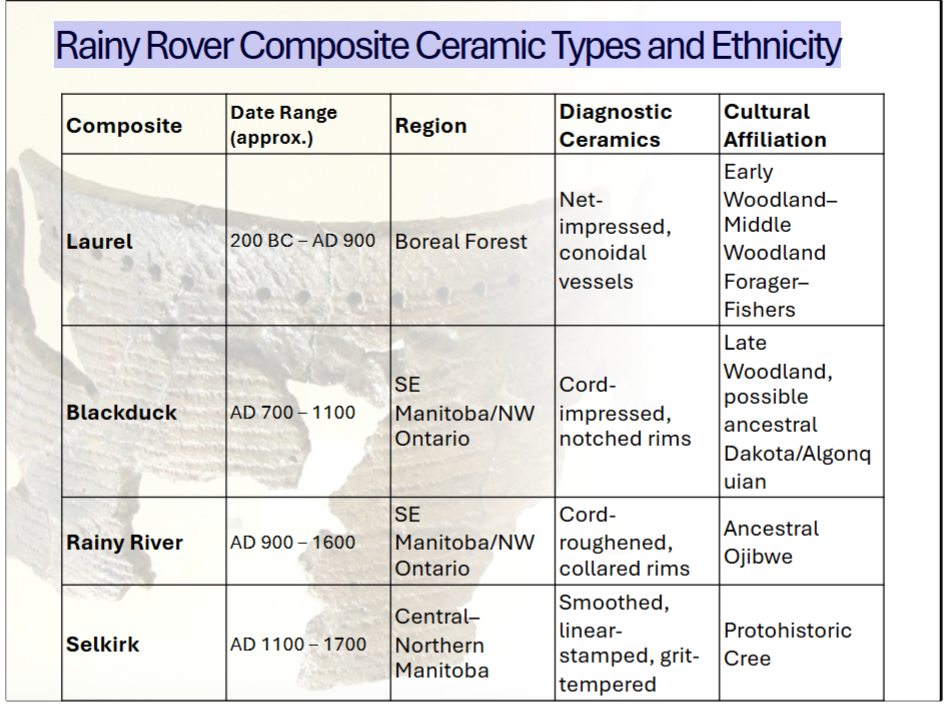

Rainy River Composite AD 900-1600

Occupies the Rainy River-Lake of the Woods drainage on the Manitoba/Ontario boarder.

A major transportation corridor, connecting Lake Winnipeg/Winnipeg river to the Great Lakes and beyond.

A mosaic environment ideal for semi- sedendary life.

Emerges out of Laurel Tradition and Black Duck Composite.

Gradual transition into Selkirk Composite and historic Ojiibwe occupation in 17 the century

Geographic and Environmental Context

The Rainy River Composite occupies the Rainy River–Lake of the Woods drainage on the Manitoba–Ontario border — a transitional zone between the boreal forest and the eastern Plains.

This region was a major transportation corridor, connecting the Winnipeg River– Lake Winnipeg system to the Great Lakes via the Rainy–Pigeon River routes. Its environmental mosaic of forests, lakes, and riverine terraces offered abundant fish, wild rice (Zizania aquatica), waterfowl, and large game, making it ideal for semi-sedentary occupations.

Chronology and Cultural Relationships

Temporal Range: ca. AD 900–1600, spanning the Late Woodland and Protohistoric periods.

Predecessors: Emerged out of the Laurel Tradition (ca. 200 BC–AD 900) and the Blackduck Composite (ca. AD 700–1100).

Successors: Gradually transitions into the Selkirk Composite farther northwest and into historic Ojibwe occupations in the 17th century.

Archaeologists interpret the Rainy River Composite as part of a Late Woodland continuum—a cultural bridge between northern boreal adaptations and southern horticultural societies

Rainy Rover Composite Ceramic Types and Ethnicity

Rainy river composite- detailed overview

3. Material Culture

Ceramics

Technological attributes: Hand-built, grit-tempered pottery; surfaces usually cord-roughened, with smoothed interiors.

Functional variation: Ceramic types suggest both domestic cooking and storage uses; large storage vessels indicate at least seasonal sedentism.

Lithics

Projectile points: Small triangular arrow points, sometimes side- or corner- notched.

Raw materials: Dominated by local cherts (Gunflint, Rainy Lake, and Hudson Bay Lowland sources).

Other tools: End scrapers, side scrapers, unifacial knives, utilized flakes, hammerstones, and ground-stone net weights.

Trade: Occasional exotic lithics (e.g., Knife River flint) indicate long-distance exchange networks extending onto the Plains

Copper and Bone Artifacts

• Native copper objects (awls, beads, fishhooks) continue from earlier Woodland traditions.

• Bone tools include awls, needles, and barbed points; some ornamentation reflects a developed symbolic aesthetic.

Settlement and Site Structure

Excavations at key sites such as Long Sault, Lockport, and Rainy River Village reveal:

Semi-permanent villages with multiple hearths and refuse middens.

Palisaded enclosures in some cases, suggesting defensive or communal structures.

Storage pits and evidence of multi-season use, indicating logistical planning and food surplus.

Burial mounds and flat interments continue Late Woodland ceremonial traditions, often with red ochre and grave goods

5. Subsistence and Economy

The Rainy River Composite reflects a broad-spectrum economy finely tuned to the local ecology: • Fishing: Central to subsistence — especially sturgeon, pike, and walleye — supported by net sinkers and fish remains.

Hunting: Moose, deer, beaver, and waterfowl.

Gathering: Wild rice, berries, nuts, and roots, complemented by small-scale horticulture (maize, squash) evident from pollen and starch-grain analyses at some sites.

Storage: Large pit features indicate planned winter caching — a step toward semi-sedentism uncommon in more northern Woodland groups.

Trade and Interaction

The Rainy River people participated in far-reaching exchange networks linking:

• Western groups: Selkirk Composite (Clearwater Lake Phase).

• Southern groups: Blackduck and Oneota traditions (Upper Mississippi).

• Eastern groups: Laurel and later Iroquoian societies.

• Artifacts such as copper, shell, and exotic lithics demonstrate cross- regional movement of goods and ideas. This network likely helped transmit both material styles (e.g., collared rims) and cosmological motifs seen in other Late Woodland art traditions.

Cultural and Ethnohistoric Interpretation

Most archaeologists interpret the Rainy River Composite as an ancestral Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) culture, representing continuity from the Laurel Tradition through to historic times.

Ethnohistoric accounts (17th-century Jesuit Relations, Radisson journals) describe large, fortified villages in the Rainy River region matching archaeological expectations.

These communities appear to have been socio-politically complex, practicing seasonal aggregation and maintaining strong kin-based ties across wide territories. The pattern aligns with early Ojibwe cultural ecology and oral traditions describing westward migration along water routes

The Plains Village Pattern in the Northeastern Plains.

Permanent or semi-permanent villages

Earth lodges

Maize horticulture

Pottery

Trade Networks

Social organization

Plains Village Pattern – Summary

The Plains Village Pattern refers to a cultural tradition that developed onthe Northern and Central Great Plainsbetween about AD 900 and 1750 (before widespread European contact). It represents a shift from highly mobile bison- hunting groups to more settled village-based communities that practiced agriculture, especially maize, beans, and squash.

Key Features

Permanent or semi-permanent villages located along major rivers (like the Missouri, Knife, and Heart Rivers).

Earthlodges or pit houses built from wood, clay, and grass formed the main dwellings.

Maize horticulture combined with continued bison hunting provided a mixed subsistence strategy.

Pottery was widespread—thick-walled, globular vessels with cord-marked or incised designs.

Trade networks connected Plains Villagers with Woodland and Southwestern cultures (for shells, obsidian, ceramics, etc.).

Social organization included extended family households and developing leadership roles, sometimes evolving into chiefdoms.

Important Regional Examples

Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara (Three Affiliated Tribes) in North Dakota are classic examples of later Plains Village societies.

Earlier expressions include complexes such as the Initial Middle Missouri, Extended Middle Missouri, Coalescent, and Central Plains traditions.

Decline and Transformation

After AD 1750, many villages were abandoned due to epidemics, warfare, and increased mobility associated with the horse and fur trade era. Many groups became the historical Plains tribes encountered by Europeans, including the Crow, Omaha, and Pawnee

Plains Woodland Cultures

• Earthworks a feature of Besant-Sonota and Avonlea groups.

Besant and Avonlea groups begin the construction of earthen mounds - some of which appear as low domes. Other earthworks are much larger, achieving lengths of almost 242 meters

• Built from 2450 years ago until AD 1000

These earthworks date to between 500 BC and AD 1000 and are usually built on bluffs overlooking valleys. Perhaps like megalithic tombs in Europe, they functioned to define group territories.

• Circular and linear in shape and roofed with logs or poles.

• Bison remains often placed with the dead

Most of these circular and linear earthworks were roofed with logs or poles, and bison skulls and carcasses were often placed with the dead indicating the significance of these animals to these peoples.

Interestingly, Hopewell ideas about individual power and prestige did not travel into the northeastern Plains.

Plains Woodland sites are often small and inconspicuous and are located on river terraces where they lie buried under alluvial deposits

Many contain the remains of maize beans and squash which become an important food staple in this area by the first millennium AD. Obviously it would have been extremely challenging to grow these crops in the eastern Plains.

The pottery produced by these early Woodland groups is coarse and heavy, and people probably lived in small thatched structures.

By AD 1000, Plains Woodland groups had changed to more sedentary societies.

They became dependent upon maize and beans, supplemented by hunting and gathering.

Good climatic conditions allowed for the spread of cultivation into the foothills of the Rockies.

Waldo Wedel calls the Plains Woodland cultures of the Missouri Valley and Kansas River area a watered-down version of Hopewell.

Late Precontact Period on the Northwestern Plains (ca. AD 1650–1750)

• Plains Cree and Assiniboine expanded westward, pushing into territories previously occupied by groups linked to Avonlea, Besant, and Late Side- Notched traditions.

• Blackfoot-speaking groups consolidated in southern Alberta, forming regional confederacies identifiable archaeologically by distinctive toolkits and site patterning.

• Ceremonial evidence: Medicine wheels, rock cairns, and petroforms from this period reflect continuity with older traditions but with increasing regional standardization — possibly signaling intergroup alliance rituals.

Definition and Chronological Context of Late Precontact Period on the Northwestern Plains (ca. AD 1650–1750)

The Late Precontact Period refers to the century or so before direct European settlement on the Northwestern Plains, roughly spanning AD 1650–1750.

During this interval, Indigenous societies were already adapting to European- introduced goods and ideas through intermediate trade networks, well before European traders, missionaries, or settlers physically entered the region.

This period bridges the late Late Precontact and early Historic periods and corresponds to what some researchers call the Protohistoric Period in Plains archaeology

Archaeological Indicators of Indirect European Contact- in late precontact period on the northwestern plains (ca. AD 1650-1750). Trade Goods and Shifts in Ceramic and Lithic Assemblages.

Although Europeans had not yet settled the region, several classes of archaeological evidence indicate indirect influence:

Trade Goods

Metal artifacts: Iron and copper knives, awls, projectile points, and kettles appear in sites predating direct contact.

Glass beads: Blue and white seed beads and larger trade beads (drawn or wound glass) occur sporadically in protohistoric burials and habitation sites (e.g., Saskatchewan River valley, Upper Assiniboine, Red Deer River).

Firearms: By ca. AD 1700, lead shot, gunflints, and brass gun parts appear in small numbers.

Other materials: Brass tinklers, bells, and silver ornaments are found in ceremonial contexts, marking the incorporation of trade goods into Indigenous symbolic economies.

Shifts in Ceramic and Lithic Assemblages

Ceramic decline: Locally made pottery declines sharply after ca. 1650, as metal pots and kettles replace them.

Lithic change: Fewer formal projectile points; increased use of gunflints and metal projectile points.

Composite assemblages: Some late sites contain a mixture of traditional lithics and imported materials — a hallmark of the transitional protohistoric period.

Archaeological Indicators of Indirect European Contact- in late precontact period on the northwestern plains (ca. AD 1650-1750). Settlement and Mobility Patterns,

Settlement and Mobility Patterns

The period is characterized by increasing mobility and intergroup realignments:

Horse introduction (post-AD 1730): Although the horse becomes dominant slightly later, evidence for increased travel and trade routes foreshadows its eventual transformative role.

Seasonal aggregation sites: Archaeological data show large bison kill and processing locales, communal camps, and ceremonial centers (medicine wheels, tipi rings) becoming more common.

Tipi rings and hearth patterns suggest highly mobile, extended-family groups organized around bison hunting economies

Subsistence and Economy

The bison economy intensified during this period:

Large-scale bison pound and drive site use (e.g., Head-Smashed-In, Estuary, Gull Lake) continues and expands.

Bone grease rendering and meat drying pits appear in higher densities, showing increased food processing for trade and storage.

Plant processing tools (grinding stones, pestles) and storage features remain common but decline after 1700 as groups adopt lighter, more mobile technologies.

This economy increasingly linked Plains groups to fur trade markets via Cree and Assiniboine middlemen who moved European goods westward in exchange for hides and pemmican.

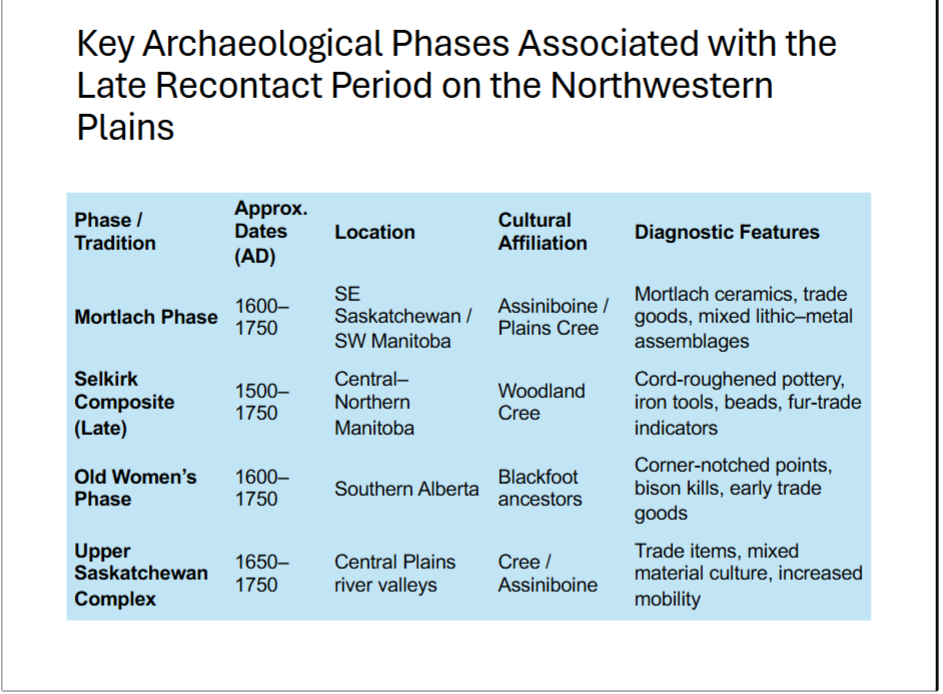

Key Archaeological Phases Associated with the Late Recontact Period on the Northwestern Plains

Regional Archaeological Expressions by the mid-18th century:

Indigenous groups on the Northwestern Plains were fully integrated into continental exchange networks extending from Hudson Bay and the Great Lakes to the Northern Plains.

Archaeological evidence shows technological hybridization, expanded trade mobility, and rapid cultural adaptation to external influences.

The groundwork was laid for the emergence of historic nations: Plains Cree, Assiniboine, and Blackfoot Confederacies.

This period represents the Indigenous transformation of colonial goods into local cultural systems, not the passive reception of European influence.

Material culture, settlement, and ritual evidence all attest to Indigenous agency and resilience in reshaping their economies, alliances, and landscapes.

Example:

Late Mortlach Phase (AD 1600–1750) is key here — characterized by the appearance of European goods in Plains Village-like contexts.

Mortlach ceramics are distinctive: cord-roughened bodies, smoothed necks, and obliquely notched rims, continuing the Blackduck–Rainy River tradition but now co-occurring with trade items.

Mortlach sites are interpreted as Assiniboine or Plains Cree settlements — early intermediaries in the expanding fur trade.