greek history exam 2

1/40

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

41 Terms

polis

A city and the surrounding territory, making a single, self-governing political unit

the citizens of that city

Synoikism

village inhabitants yield deliberative power and authority to a central city

boulê

the council; held most power early on; tasked with making policy, drafting laws, handle daily affairs; decisions are sent to the assembly

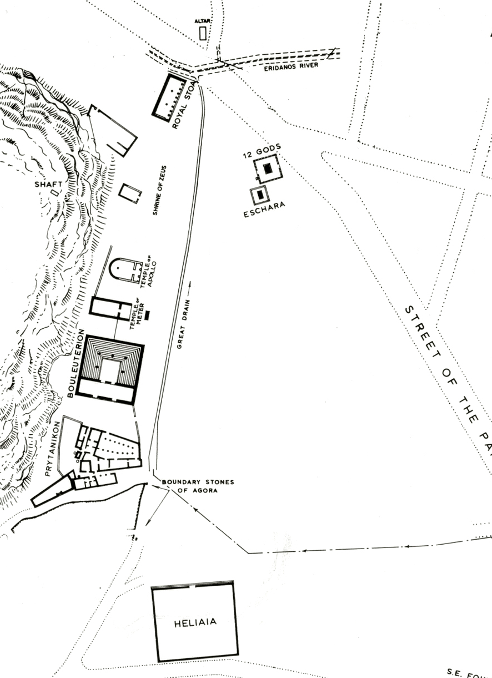

agora

meeting place, marketplace, (originally the assembly)

hoplite

a heavily armed foot soldier in ancient Greece, typically fighting in a phalanx formation

Archon

A common title (“leader”) for the

highest-ranking magistrate in the early

city-states. During the Classical period,

even when the strate¯goi had become the

most important officials in Athens,

tyrant

a ruler who seized power unconstitutionally, not necessarily an evil one as the term is used today. Tyrants often rose to power during periods of instability and could be popular, overseeing eras of prosperity and public works, though some later became oppressive.

Polykrates of Samos

Polycrates, son of Aeaces, was the tyrant of Samos from the 540s BC to 522 BC. He had a reputation as both a fierce warrior and an enlightened tyrant.

Solon

an archaic Athenian statesman, lawmaker, political philosopher, and poet

Peisistratus

is known for establishing himself as a benevolent tyrant of Athens, bringing economic prosperity, cultural advancement, and political stability by supporting common farmers, beautifying the city with public works, patronizing the arts, and expanding religious festivals like the Panathenaic Games and Dionysia, which helped transform Athens into a powerful center of Greece.

tyrannicides

Two lovers in Classical Athens who became known as the Tyrannicides for their assassination of Hipparchus.

oikistis

a leader of a new colony in ancient Greece, chosen by the parent city-state to guide the founding of a new settlement.

pithekoussai

an ancient Greek colony on an volcanic island founded around the mid-8th century BCE. It was a major trading emporium for its time, known for its diverse population and the discovery of the famous Nestor's Cup.

phalanx

was a rectangular mass military formation, usually composed entirely of heavy infantry armed with spears, pikes, sarissas, or similar polearms tightly packed together.

tyrtaios

Tyrtaeus was a Greek lyric poet from Sparta, active in the mid-7th century BCE. He is known for his martial elegies, which were designed to inspire Spartan soldiers with courage and a sense of duty, particularly during the Second Messenian War

hoplon

The distinctive large, convex, circular shield used by hoplite soldiers in ancient Greece. Typically made of wood faced with bronze, it was a crucial piece of armor for both defense and offense in the phalanx formation, giving the hoplite (heavy infantry soldier) his name.

chryselephantine

A sculptural technique that involves the use of gold (chrysos) and ivory (elephantinos) for creating statues. This technique was highly prized in ancient Greece, often used for cult statues, where ivory was typically used for the flesh and gold for drapery and hair.

pythia

The title of the High Priestess who served as the Oracle of Apollo at Delphi. The Pythia delivered prophecies from the god, typically while in a trance, seated on a tripod over a chasm.

kouros

A type of freestanding ancient Greek sculpture, typically depicting a nude young male. Kouroi (plural) were often used as grave markers or votive offerings and are characterized by a rigid, frontal pose, a slight archaic smile, and an idealized athletic physique.

kore

free-standing ancient Greek sculpture of the Archaic period depicting female figures, always of a young age.

artemis orthia

refers to the goddess Artemis in her aspect as Orthia, a deity of salvation, fertility, and protector of children and vegetation

lykourgos

was the legendary lawgiver of Sparta, credited with the formation of its eunomia, involving political, economic, and social reforms to produce a military-oriented Spartan society in accordance with the Delphic oracle.

helot

a serf or state-owned slave in ancient Sparta, who was bound to the land to perform agricultural and other labor. They formed the lowest class in Spartan society, outnumbering the Spartans and creating a constant fear of revolt, which led to extreme and brutal measures of control

eponymous heroes

the main character of a work (such as a novel, play, or film) whose name is also the title of that work. For example, the eponymous hero of The Odyssey is Odysseus. A marble podium that bore the bronze statues of the heroes representing the phylai (tribes) of Athens.

royal stoa

an important ancient Greek building in the Athenian Agora, the administrative seat of the Archon Basileus (King Archon), who was in charge of religious affairs. It was originally built in the 6th century BCE and was considered a significant site for the display of laws and the taking of oaths by magistrates.

persepolis

modern-day Iran, near the city of Shiraz, not Greece. It was the ceremonial capital of the Persian Empire, founded by Darius I around 515 BCE, and was destroyed by Alexander the Great of Macedon in 330 BCE.

prozkynesis

Greek name for the Persian

ritual greeting that social inferiors offered

to their superiors and all Persians offered

to the Persian king.

xerxes

Xerxes I, commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 486 BC until his assassination in 465 BC. He was the son of Darius

thermistokles

Athenian politician and general. He was one of a new breed of non-aristocratic politicians who rose to prominence in the early years of the Athenian democracy.

The Creation of Identity in the Archaic Period essay

The Archaic Period (c. 800–480 BCE) marked the birth of collective and individual identity in Greek society. Identity during this time shifted from tribal affiliation toward civic belonging within the polis, the city-state that became the foundation of Greek life. The rise of the polis gave individuals a defined political and social role. For example, in Athens and Sparta alike, citizens gained a sense of self through participation in communal institutions such as the assembly or military training. This development illustrates how identity became tied to shared duties rather than lineage alone.

Homeric values also shaped identity by defining what it meant to be honorable. In the Iliad and Odyssey, heroes like Achilles and Odysseus embody aretē—excellence achieved through courage, skill, and intelligence. These epics provided moral models that guided later Greek behavior, showing that one’s identity was not inherited but earned through action and virtue. This literary evidence reveals how ideals of heroism laid the groundwork for civic pride and competition in the polis.

Religious festivals further reinforced identity. Panhellenic games at Olympia united Greeks under common gods while preserving regional distinctions. Participation signified both local and pan-Greek belonging. Together, the polis, heroic ideals, and shared rituals created a layered sense of self that blended individual excellence with communal loyalty—the essence of Greek identity in the Archaic Period.

The Trappings of Aristocratic Life in the Archaic Period essay

Aristocratic life in the Archaic Period was defined by wealth, leisure, and the display of social superiority. The elite distinguished themselves through symposia—exclusive drinking parties where poetry, conversation, and politics intertwined. These gatherings were more than indulgence; they symbolized refined culture and the intellectual dominance of the upper class. For instance, poets like Alcaeus and Theognis described aristocratic values of friendship, loyalty, and disdain for the “base-born,” illustrating how leisure and poetry reinforced social boundaries.

Material wealth also played a crucial role in expressing status. Aristocrats owned land, horses, and slaves—visible indicators of economic power. In warfare, they fought as hoplites who could afford their own armor, linking military honor with class privilege. This exclusivity shows how political power and social standing were intertwined, as only those of means could participate in the defense and governance of the polis.

Even religious and athletic festivals reflected aristocratic dominance. Victories at Olympia or Delphi were public affirmations of prestige, often immortalized through statues and odes. These trappings of wealth and achievement were not mere vanity—they legitimized aristocratic authority in a society gradually moving toward broader participation. Thus, the aristocracy used luxury, leisure, and public display to assert their superiority and maintain influence during a time of social transformation.

The Role of Themistokles in the Course of the Persian Wars essay

Themistokles was pivotal in shaping Greece’s victory over Persia and its emergence as a naval power. His foresight in expanding Athens’ navy before the invasion demonstrated both strategic intelligence and political boldness. When Athens discovered silver at Laurion, Themistokles persuaded the assembly to invest in triremes rather than distribute the wealth among citizens. This decision, initially controversial, proved decisive when Xerxes’ vast fleet attacked in 480 BCE. The fleet Themistokles built became the backbone of Greek resistance at Salamis.

At Salamis, Themistokles’ leadership and cunning secured a turning point in the war. He used deceptive tactics to lure the Persian navy into the narrow straits, where Greek maneuverability neutralized Persian numbers. The outcome crippled Xerxes’ naval strength and forced his retreat. This evidence illustrates Themistokles’ mastery of psychological and strategic warfare—qualities that defined Athenian resilience.

Beyond the battlefield, Themistokles shaped the political identity of Athens. His promotion of naval power elevated the poorer thetes who rowed the ships, fostering democratic participation. Thus, his role extended beyond military victory; he transformed Athens into a maritime democracy. Themistokles’ vision and actions not only repelled Persia but also laid the foundations for Athens’ Golden Age.

sparta

salamis

thermopylae

athens

marathon

ionia

persia

sardis

argora