9 - The discharge of contracts

1/42

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

43 Terms

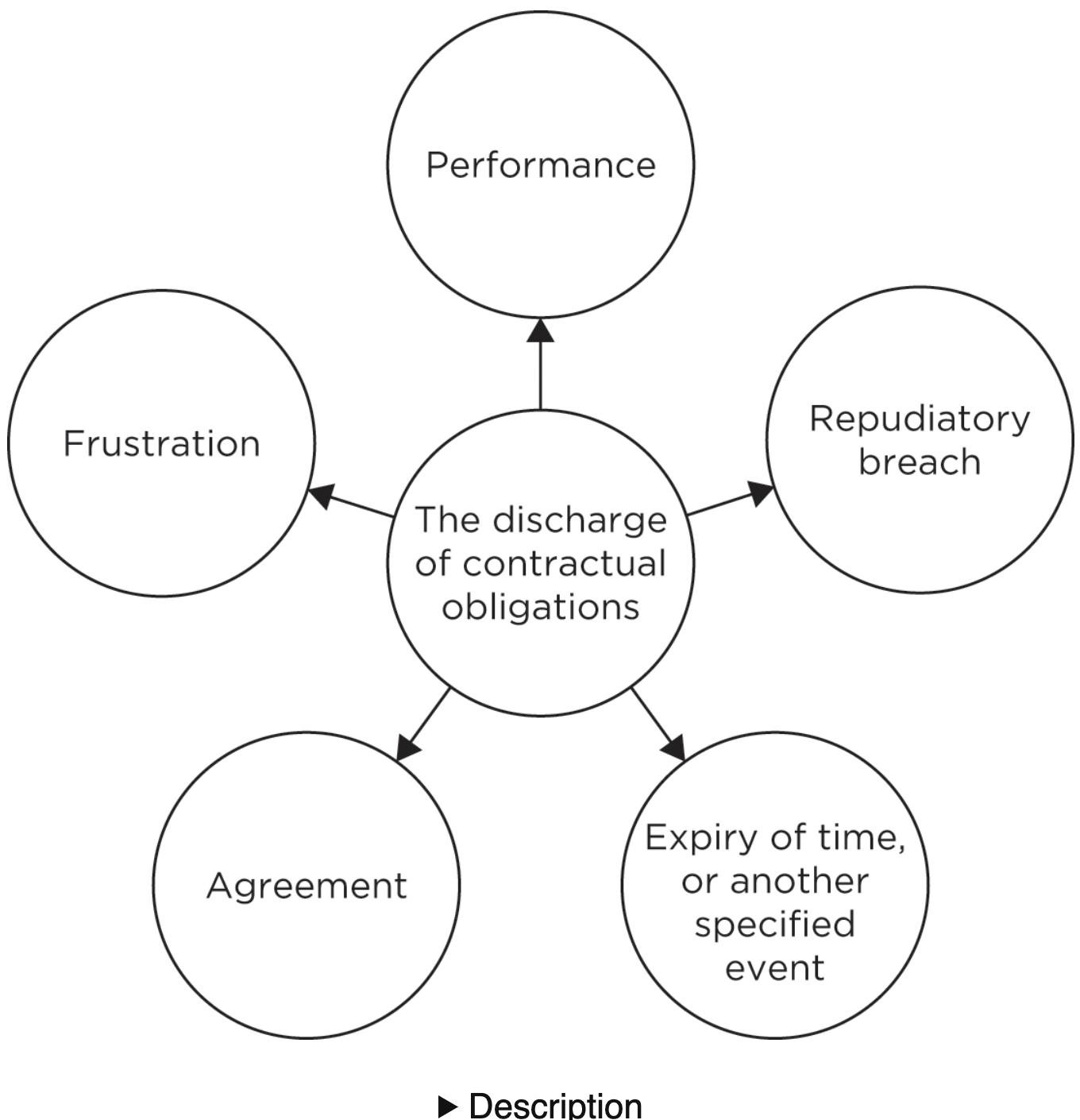

See diagram. Different ways in which contracts are discharged: - performance - repudiatory breach - expiry of time, or another specified event - agreement - frustration

What is the statutory guidance in the B2B context?

The Sale of Goods Act (SGA) 1979 implies certain terms into contracts for the sale of goods as conditions:

goods will match their description (s 13 (1) of the SGA 1979),

goods sold in the course of a business are of satisfactory quality (s 14 (2) of the SGA 1979) and

where goods are sold by sample the bulk will correspond with the sample in quality (s 15 (2) of the SGA 1979).

This is important because it tells us that these implied terms are conditions so that the breach of such terms is a repudiatory breach.

However, note that there is an exception to the general rule under s 15A of the SGA 1979, which provides that if the breach of the relevant condition is so slight that it would be unreasonable for the buyer to reject the goods, the relevant conditions will be treated as a warranty.

Exam warning: unfortunately, there is no judicial guidance on how s 15A SGA 1979 is interpreted in practice, so you will need to watch out in scenarios when you are told that the breach of the implied terms is very slight, and the buyer uses the goods supplied for the purpose that they originally intended. In such circumstances, it is likely that s 15A SGA 1979 will apply so that it will be unreasonable for the buyer to treat the breach as a repudiatory breach.

What is the statutory guidance in the B2C context?

The B2C context is governed by the Consumer Rights Act (CRA) 2015. Sections 19 to 24 of the CRA 2015 set out the various remedies available to consumers for breach, including the short-term right to reject, the partial right to reject, the right to repair or replacement, the right to a price reduction, or a refund in the case of a contract relating to a digital content. There are limited circumstances in which a party may treat a contract as at an end, including if the parties state that an express term is a condition. The SQE1 assessment specification has not stated that candidates need to be aware of consumer remedies and they will not be discussed in this section.

What are warranties?

Warranties are contractual provisions whose breach does not undermine the overall purpose of the contract. So a breach of warranty is not repudiatory breach, and the contract remains in force after the breach, but gives the non-breaching party a remedy in damages.

What are the facts of Bettini?

Mr Rossini is an opera singer who agrees with Mr Smith to perform Italian opera in Mr Smith’s theatre, and also in halls and private houses in the United Kingdom between 30 March and 13 July for £10,000 per month pro rata. In the agreement, Mr Rossini also agrees not to perform opera within 50 miles of London from 1 January until 30 March, unless agreed with Mr Smith. In addition, Mr Rossini agrees to arrive six days in advance of 30 March to participate in rehearsals. Due to illness, Mr Rossini only manages to arrive three days before 30 March.

Can Mr Smith discharge Mr Rossini of his obligations under the contract on the grounds of repudiatory breach?

The answer is no. This scenario is based on Bettini v Gye (1876) QBD 183. The court considered that the requirement for the singer to be in London six days before 30 March was not a condition. In reaching this conclusion the court took into consideration the relative importance of all the terms in the agreement, including the singer’s agreement not to sing within 50 miles of London from 1 January of the same year. The court also considered the requirement that the singer would not only sing at the theatre (where it admitted that his presence for the rehearsals was vital), but in addition, the singer was to sing in halls and private houses over a relatively long period of time, and also that, despite arriving only three days in advance of 30 March, the singer was able to perform his other obligations under the contract.

What are innominate terms?

In some scenarios, it is not clear whether a particular provision is a condition or a warranty - these provisions are known as innominate (unclassified) terms. This lack of clarity may be due to the fact that the contract does not label a particular provision as a condition or a warranty. In such cases, the courts decide whether the provision is a condition or a warranty. In such cases, the courts decide whether the provision is a condition or a warranty by considering the effect of the breach at the time it occurs. As a general approach, if an innominate term is breached, the courts only classify it as a condition if the breach deprives the non-breaching party of substantially all the benefit of the contract.

Define Cehave.

Fodder & Co. agreed to sell animal food to Holland & Co. for £100,000. The contra t provided that the animal food must be shipped in good condition. The market price for animal food must be shipped in good condition. The market price for animal food dropped after the contract was concluded, but before the cargo was delivered. On delivery, Holland & Co., found that some of the cargo was damaged. Holland & Co. treated the delivery of partially damaged animal foods as a breach of the obligation to deliver animal food in good condition, and that this was a breach of condition, which allowed it to repudiate the contract. Fodder & Co, disagreed, but because Holland & Co. refused to take delivery of the animal food, Fodder & Co sold it to a third party for £30,000. The third party then sold the animal food to Holland & Co., which then used the entire cargo to make animal food. Was Holland & Co. entitled to treat Fodder & Co’s breach of the provision to deliver in ‘good condition’ as a breach of a condition that allowed it to reject the entire cargo?

The answer is no. This scenario is based on Cehave N.v v Bremer Handelsgesellschaft MBH [1976] QB 44. The court held that the provision that the cargo be made ‘in good condition’ was not a condition. It was an innominate term. The court concluded that because the buyer used the entire cargo for its original purpose (after it bought it from the third party), the breach did not go to the root of the contract or deprive the buyer of substantially the whole benefit of the contract. this meant that although the buyer was entitled to a remedy in damages because some of the cargo was not in good condition, it was not entitled to treat the breach as a repudiatory breach of condition.

Exam warning: one of the reasons why the courts will intervene on the remedy for a breached innominate term is to avoid the non-breaching party from discharging a contract due to the breach of a provision of minor importance to the contract as a whole. So watch out in scenarios for attempts by a non-breaching party to discharge a contract in the case of a breach of the innominate term. In such scenarios, unless the provision specifically states that the breach of the provision allows the non-breaching party to repudiate the contract, the courts will apply the innominate term analysis. This analysis means that unless the breach goes to the root of the contract, or deprives the non-breaching party of substantially the whole benefit of the contract, the breach will not be a repudiatory breach.

What is the entire obligations rule?

Some agreements are drafted so that party A must perform all of his obligations under a contract before party B is required to pay party A. Such agreements are called entire obligations agreements. For example, where a contract provides that party A will be paid £1,000 if he travels to Jamaica to deliver a letter to party B, party A will not be able to claim any part of the £1,000 (for example, on a quantum meruit basis) if he fails to deliver the letter, even if he has spent time and money in attempting to do so.

Define quantum merit.

Quantum merit: a remedy that allows a party to claim a reasonable amount for the benefit conferred to the other party under a contract.

How do you mitigate the effect of the entire obligations rule?

In practice, there are three ways in which the entire obligations rule can be mitigated:

severable contract,

the acceptance of the performance by the other party, and

the doctrine of substantial performance.

What are severable contracts?

Contracts can be drafted to provide for work to be performed in stages, requiring the other party to make payments in instalments after the completion of each stage of performance.

What is the acceptance of the performance by the other party?

If the non-breaching party chooses to accept the performance of the party in breach, the party in breach can claim for the benefit of the work he has carried out on a quantum meruit basis. A quantum meruit claim can only be made if the non-breaching party can choose whether or not to accept performance.

What are the facts of Sumpter?

Bertie agrees to build two houses on Elizabeth’s land. The contract provides that Elizabeth will pay Bertie the full amount of the contract (£565) after he has completed building the two houses. Unfortunately for Bertie, he runs out of money halfway through the project, when the value of the work he he has completed is £333. Bertie abandons the half-completed houses and leaves materials on Elizabeth’s land. Elizabeth completes building the houses herself with the materials that Bertie had left on the land. Can Bertie recover payment for the work he has done, and for the materials that he left on the land?

Bertie cannot recover payment for the work he has done, but he can recover payment for the materials left on the land. This scenario is based on Sumpter v Hedges [1898] 1 QB 673 CA. The court’s decision was driven by the fact that the contract was an entire obligations agreement where the other party’s payment obligation only arose on the builder’s completion of the two houses. Further, the other party had no choice but to accept the builder’s performance of the half-completed houses. By contrast, the other party was free to choose whether to complete the building using the materials left by the builder on the land, or any other materials. On the grounds that the other party chose to use the materials left by the builder, the court allowed the builder to recover the value of the materials left on land.

Exam warning: check carefully in scenarios that relate to entire obligations whether the non-breaching party can choose to accept any part of the performance. If the non-breaching party is free to choose, and does choose to accept any part of the performance, he will be liable to pay the other party on a quantum meruit basis for that part of work that he has chosen to accept.

What is the doctrine of substantial performance?

The doctrine of substantial performance provides an important mechanism in respect of entire obligations agreements.

Substantial performance: the doctrine that allows a party to recover a substantial part of his fee if he has substantially completed his performance, albeit with defects, under an entire obligations agreement.

What are the facts of Hoenig?

Louisa is an interior designer who agrees to decorate and furnish Charlie’s home for a lump sum payable on completion of £750. Louisa completes her work on Charlie’s home, but Charlie refuses to pay the amount owed to Louisa on the grounds that part of the Louisa’s work was defective. Specifically, Charlie argues that Louisa’s work is defective in respect of a wardrobe and a bookcase. The evidence shows that it would cost £55 to fix the defects in the wardrobe and the bookcase.

Can Louisa force Charlie to pay her under the doctrine of substantial performance?

The answer is yes. Louisa can force Charlie to pay her the full amount under the contract, less the amount required to fix the defects. This scenario is based on Hoenig v Isaacs [1952] 2 All ER 176. The court held that not every breach of an entire obligations agreement allows the non-breaching party to discharge the contract. Discharge is only permitted for breaches that go to the root of the contract, for example, where work is abandoned when it is only half finished. This means that where the work has been completed, albeit with some minor defects, the non-breaching party must pay the price agreed under the contract, minus a deduction to fix the defects.

Revision tip: look carefully at the case law on this topic. The doctrine of substantial performance only applies in respect of minor defects. The case law provides clear examples of scenarios in which the courts have held that the amount (or value) of the work performed is not enough for the doctrine of substantial performance to apply.

What is the expiry of time or other specific events?

A contract may provide that it will end after a certain period of time, or when a specified event happens. For example, an energy supplier may wish to limit an obligation to supply energy at a given price until the energy regulator next reviews its pricing to suppliers. This will allow them to supply energy to a customer at a given price for as long as they are aware of what the supply price is. Provided these are correctly drafted, the expiry of the time frame or the occurrence of the specified event will bring the contract to an end.

What is agreement?

Another way in which parties are discharged of their obligations under a contract is through their agreement. The parties simply need to agree to release each other from any outstanding obligations.

What is frustration?

Frustration is an English law doctrine that automatically discharges both parties from their future obligations under a contract. Frustration takes effect as a result of events that make the future performance of a contract:

impossible,

illegal, or

where the main purpose of both parties of the contract is lost.

Frustration: a doctrine that automatically discharges both parties from their future obligations under a contract.

What is the legal effect of frustration?

It is essential to understand that frustration automatically discharges both parties from their outstanding obligations under a contract. This contrasts with the effect of a repudiatory breach, which gives the non-breaching party the choice to discharge the contract, or to affirm it.

If the parties to a contract have already performed some obligations under the contract, the position is regulated by the Law Reform (Frustrated Contracts) Act 1943. We will explore how this works in practice below (see The effect of frustration on financial obligation).

How do you identify frustration?

In your SQE1 assessments, you need to look out for scenarios in which the performance of the contract following a specific event is fundamentally different from what was contemplated by the parties when the agreement was concluded. Make sure that you understand that the doctrine does not apply if the contract has become more difficult, expensive or inconvenient to perform. Parties are expected to provide for such eventualities in their contracts through clauses that allow them to increase their costs if, for example, materials or labour becomes more expensive.

What are the facts of Davis?

Jones Contractors agree with a council to build 78 houses for a given amount within eight months. The work takes 22 months and costs Jones Contractors more than they had planned; this was due to a shortage of materials and a shortage of labour. Does Jones Contractors have grounds to claim that the contract is frustrated?

The answer is no. This scenario is based on the case of Davis Contractors v Fareham UDC [1956] AC 696. The House of Lords held that the contractor had accepted the risk of the cost being more or less than he expected. The delay was not caused by a new or unforeseeable factor or event. So although the contractor’s job became more difficult, it had not become a job that was different from what was contemplated in the original contract. So the contract was not frustrated.

In addition, the courts will not allow a claim for frustration where the event in question is self-induced, or results from the fault of one of the parties (see frustration and fault).

What are the rules for frustration when performance is impossible?

The impossibility of performing a contractual obligation may be a ground on which a contract is held to be frustrated. Note the importance of the word may, which means that in some cases a contract that has become impossible to perform will not be held to be frustrated. We will explore these cases in the following sections.

What is frustration due to impossibility when the subject matter is destroyed?

A contract may be held to be frustrated when its subject matter is destroyed and this makes the contract impossible to perform. For example, in Taylor v Caldwell (1863) 122 ER 309, the destruction of a concert hall by fire was held to frustrate a contract in which concerts were to be held in the concert hall. Neither party to the contract was to blame for the fire. The court’s logic was that the parties had contracted on the basis that the existence of the concert hall was essential to the performance of the contract.

What is frustration due to impossibility where a person is ill or dies?

Many contracts can be fulfilled by any one of a number of individuals so that if one individual in a team is ill or dies, the contract is not frustrated. But if a contract is specific to a particular person, the illness or death of such person can serve as a ground to discharge the contract for frustration. The classic example is provided in the case of Robinson v Davison (1870-71) LR 6 Ex 269 where the contract provided for a specific woman to play the piano at a concert given by the other party on a specific day. The woman was unable to perform on the day in question due to illness. The court held that the contract was frustrated.

What are the rules for frustration due to impossibility where the agreed means of performance becomes unavailable?

In scenarios where the parties have agreed that the contract will be performed by a specific means (for example, delivery on a named boat), the unavailability of such means will be held to frustrate the contract.

Note that in scenarios where the means of performance is only temporarily unavailable, you will need to consider all of the information in the scenario, including the duration of the unavailability. If the temporary delay is so long that the purpose for which the means of performance (for example, a ship) was originally hired has become very different, then the contract is likely to be frustrated. For example, if a ship hired to collect a commodity is unavailable for eight months.

Revision tip: make sure that you distinguish between scenarios in which the means of performance that has become unavailable is a term of the contract, and scenarios in which the parties envisage that contract will be performed in a specific way (for example, by following a particular route), but they have not expressly agreed this route in the contract. This distinction is critically important because if the route (or other means of performance) is not an agreed term of the contract (but is simply envisaged by the parties) the fact that the route (or means of performance) is no longer available will not frustrate the contract.

What are the rules for frustration when performance is illegal?

If, after a contract has been concluded, the law changes in such a way that renders the future performance of the correct illegal, this can frustrate the contract if the new law would have made performance of the contract illegal at the time the contract was made.

What are the rules for frustration when the main purpose of both parties to the contract is lost?

A further way in which a contract is frustrated is where the main purpose of both parties to the contract is lost. So although it may be possible for both parties to perform the contract, a dramatic change in the surrounding circumstances means that the entire basis on which the contract was concluded has been lost. For example, in Krell v Henry [1903] 2 KB 740 CA, a contract to hire rooms on a specific date at a higher than usual price on Pall Mall to watch the coronation procession of King Edward VII was held to be frustrated when the coronation procession was postponed. Although the contract could still be performed because the rooms could still be used for a social gathering, the purpose of hiring the rooms in that location at such a high price with the main purpose of watching the coronation had been lost.

What are the rules for frustration and fault?

A key element in any claim for frustration is that it should not result from the act or choice of the party that seeks to rely on it.

What are the facts of the J. Lauritzen?

Morritson Drilling agreed with Tarzan Shipping that Tarzan Shipping would transport Morritson’s shipping rig either on its ship Greystoke 1, or on its other ship, Greystoke 2. Tarzan Shipping intends to use Greystroke 2, but this is not mentioned or recorded in the contract. Since Tarzan Shipping intends to use Greystroke 2, it agrees to hire out Greystoke 1 to a third party. Due to unforeseen circumstances, Greystoke 2 sinks and cannot be used. Greystoke 1 is not available because it is being used by a third party. Can Tarzan Shipping claim that the contract is frustrated?

The answer is no. This scenario is based on J. Lauritzen A/S & Wijsmuller BV, The Super Servant Two [1990] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 1. The Court of Appeal highlighted the point that an essential requirement for frustration is that the event must significantly change the nature of the outstanding contractual obligations from what the parties could reasonably have contemplated at the time the contract was made. In this scenario, the contract provided an alternative to the ship that had sunk. The fact that the alternative ship was no longer available was the fault of the shipping company that had hired it to a third party.

What is the effect of frustration on financial obligations?

We have already seen that frustration automatically discharges both parties from all future obligations under the contract. In this section, we will explore the effect of frustration where a party to the contract has already paid money, or incurred expenses under the contract. We will also set out the effect of frustration on future obligations to pay under a contract. The position is governed generally by the Law Reform (Frustrated Contracts) Act (LRFCA) 1943, or under the common law, where the Act does not apply. Scenarios where the LRFCA 1943 does not apply include those where the parties have included provisions to deal with the consequences of frustration. In such cases, the contractual provisions will apply. The LRFCA 1943 does not apply to certain types of insurance contract, but this topic will not be discussed in this book.

What is the effect of frustration on claims for money?

If the LRFCA 1943 applies:

money paid under the contract is recoverable by the party that paid it, and

money due to be paid no longer needs to be paid.

But note carefully that if the party to whom money was paid under a contract has incurred expenses under the contract before it is frustrated, the court may, having regard to all of the circumstances, allow such person to retain an amount of money received under the contract (or recover an amount that was payable before the contract was discharged). So if a person has incurred expenses in excess of the amount he has received under the contract and the other party was not obliged to pay any further amounts before the contract was discharged, he cannot recover the excess.

Similarly, if one party has received a valuable benefit from the other party before the contract is frustrated, the court may allow the party that has conferred the benefit to recover from the other party an amount to reflect that benefit. The court takes into account all the circumstances of the case, and, in particular, any expenses recovered and the events that led to the frustration in the first place.