PHONETICS BLOCK 1

stops

Stops are sounds whose articulation involves a complete closure. Consonant sounds produced by obstructing airflow in the vocal tract, then releasing it, such as /p/, /t/, and /k/. We cannot pronounce them continuously for a long time. They are plosives and affricates.

continuants

Consonant sounds produced with continuous airflow, such as /s/, /m/, and /l/, allowing for prolonged pronunciation.

1/38

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

39 Terms

stops

Stops are sounds whose articulation involves a complete closure. Consonant sounds produced by obstructing airflow in the vocal tract, then releasing it, such as /p/, /t/, and /k/. We cannot pronounce them continuously for a long time. They are plosives and affricates.

continuants

Consonant sounds produced with continuous airflow, such as /s/, /m/, and /l/, allowing for prolonged pronunciation.

contoids

Consonant sounds that involve obstruction in the vocal tract.

Consonantal Contoids (i.e., – nuclear function; + obstruction): These would coincide with the traditional unproblematic consonants: /p, f, tʃ, m, ŋ, l, .../

Vocalic Contoids (i.e., + nuclear function; + obstruction): Here we have /m, n, ŋ, l/, which incorporate some major contact at the mouth, but may be sometimes found at the nucleus of the syllable, for example in words like ‘little, cotton, bacon, happen’.

vocoids

Consonant sounds produced without obstruction of airflow, resembling vowels, such as /j/ and /w/.

plosives

Consonant sounds produced by obstructing airflow, followed by a release, such as /p/, /t/, and /k/. Velum up; Closure + Compression + Sudden Release

a. Closure: All plosives imply a complete closure at some point of the vocal tract. | |

Glottal Closure | |

Velar Closure /k, g/ | |

Alveolar Closure /t, d/ | |

Bilabial Closure /p, b/ | |

b. Compression: Closure is held long enough for air pressure to build up. c. Release: Pressured air is released suddenly. |

affricates

Consonant sounds that are produced by a combination of a plosive and a fricative. They begin with a complete closure that is released into a narrow constriction, such as /tʃ/ and /dʒ/.

Velum up; Closure + Compression + Gradual Release (friction)

a. Closure: All affricates imply a complete closure at some point of the vocal tract.

Palato Alveolar Closure: /t], d3/

b. Compression: After closure, there is some compression.

c. Gradual Release: Air is released more slowly than with plosives so that an auditory effect is produced known as friction.

fricatives

Consonant sounds produced by forcing air through a narrow constriction in the vocal tract, creating a turbulent airflow. Examples include /f/, /v/, /s/, and /z/.

velum up; a light contact + friction; b. contact + groove + friction

a. Some fricatives imply a light contact between two articulators which lets the air break through, producing an auditory effect known as friction.

Labio-dental /f, v/

Dental /0, o/

Glottal /h/

b. Other fricatives (sibilants) imply a kind of contact which lets the air flow out through a narrow groove, producing an effect of friction.

Alveolar /s, z/

Palato-alveolar /5, 3/

nasals

Consonant sounds produced with airflow through the nasal cavity, such as /m/, /n/, and /ŋ/. They require the velum to be lowered to allow air to escape through the nose.

Velum down; Closure; nasal resonance

a. Closure: All nasals imply a complete closure at some point of the vocal tract. | |

Velar Closure /n/ | |

Alveolar Closure /n/ | |

Bilabial Closure /m/ | |

b. There is no compression nor release, because the velum is down, and the air escapes freely through the nasal cavity (adding nasal resonance). |

taps

Consonant sounds produced by a quick, light contact of the tongue with the alveolar ridge, resulting in a single rapid movement. An example is the Spanish "r" in "pero."

Velum up; striking

The articulation of a tap implies the light and rapid striking of an articulator against a point of articulation.

Apico-Alveolar Tap [r].

approximants

Velum up; approximation - friction

The articulation of approximants implies the approximation of two articulators, so that the air flows out through a narrow aperture, without producing friction

Dorso-palatal approximation: /j/

Labial-velar approximation: /w/

Lateral approximation: Lateral approximation implies a contact of two articulators that leaves an opening at both sides through which the air flows out without friction: /l/

Post-alveolar approximation: B. P. /r/.

obstruents

Obstruents are a category of consonant sounds in phonetics that are produced with a constriction or blockage of airflow in the vocal tract. This category includes plosives, fricatives, and affricates.

sonorants

Sonorants are a class of speech sounds that are produced without obstruction of the airflow in the vocal tract, doesn’t have a noise component. English Sonorants are Nasals and Approximants.

They are voiced sounds, meaning that the vocal cords vibrate during their production.

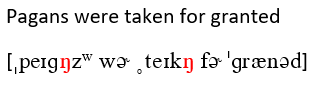

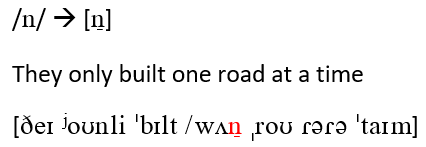

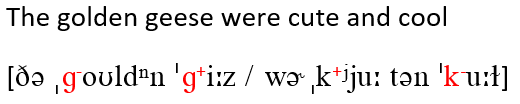

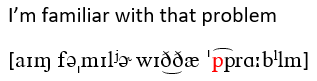

elision

Elision is the process by which a segment or part of a segment appears in the phonemic representation of a word, but is not realized at the phonetic level, usually due to the influence of certain phonetic contexts. For example, a /t/ is often elided when it occurs between voiceless consonants.

T o D entre consonantes se quita, la R no se considera como consonante.

Elision may affect consonants as well as vowels. In this course, we will also distinguish between elisions and partial elisions.

In partial elisions, one of the features that typically constitutes the sound is lost. A plosive that retains its closure and its compression stages but that has lost its explosive component (non-audible release, unreleased), for example, will be considered here a case of partial elision.

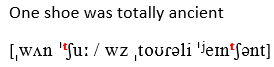

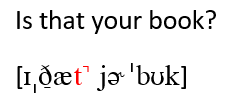

non-audible release (partial elision - plosives without release)

When followed by silence, natives often articulate a plosive with a non-audible release.

They delay the release, expand the oral cavity in order to decompress it a bit, lower the velum in order to totally reduce air pressure, and then undo the closure.

At this point, there is no air pressure to cause any plosive effect. This is a very frequent feature in everyday speech, and it affects final /t, d/ more than any other plosive.

When a plosive is immediately followed by another stop (plosive or affricate), the former will be produced unreleased. This means that we close for the first plosive, and initiate compression, but before releasing, we articulate the second stop, and we release the second stop. That is, we close, we compress, we modify closure, and then we release. The first stop, as such, remains unreleased. The compression of the first stop is lengthened so as to encompass that of the second. And then we release the second stop naturally. The unreleased realization is compulsory--if you do not perform it, the utterance sounds awkward. Unreleased realization happens within the word:

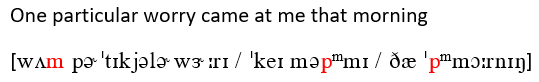

gradation

The weakening of unstressed syllables in English responds to what phoneticians call a process of gradation. When brought to the extreme, gradation leads to elision; and further, to syllable reduction (loss of one syllable) and syncopation (loss of a syllable in the middle of a word).

syncopation

Loss of a syllable in the middle of a word.

syllable reduction

Loss of one syllable in a word. Example: potato-tato.

homorganic and heterorganic nasal release (nasal release)

The release stage of a plosive also disappears when the plosive is immediately followed by a homorganic nasal:

What happens here is that we close for /t/, and there is compression; but then, the velum goes down and the compressed air flows out through the nasal cavity. There is no plosion at the alveolar ridge because the /t/ simply transforms into /n/ by lowering the velum and introducing voice. In homorganic combinations, nasal release introduces much fluidity:

Heterorganic nasal release implies a modification of the point of closure, similar to the one we had in the unreleased realization of plosives. Once the place of articulation has been modified, air pressure is simply relieved through the nasal cavity. In homorganic nasal release there is no plosion either.

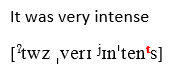

epenthesis

The opposite of elision also happens in English. That is, we will find segments in the phonetic level (or phonetic representation) that are not present in the phonemic level (or phonemic representation). This is what we call epenthesis. In English we often obtain epenthetic /t, p/ between their homorganic nasals and a sibilant fricative.

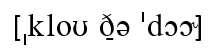

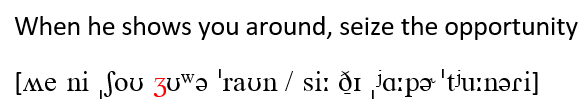

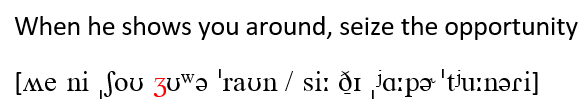

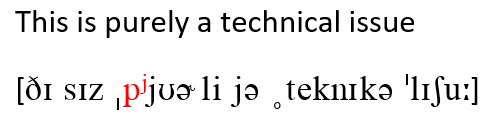

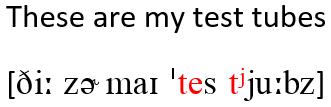

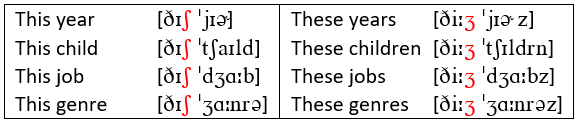

linking / liaison

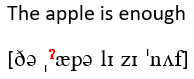

Linking: the redistribution of the syllabic structure, so that a consonant which is part of a syllable, becomes part of another syllable instead.

This is the first issue we have to consider in relation to linking in English: a consonant followed by a vowel that belongs to a different syllable will acquire an onset stricture, even if it belongs to the coda of its syllable. So, when we pronounce sass in isolation, the second /s/ has weaker (coda) stricture than the first, but if we say sass and belle, then both /s/ are equally strict (onset structure for both). In the latter case, the second /s/ behaves as if it was part of the introduced syllable: sa sen bel. It catches an onset.

This is linking in its most basic form, and what some phoneticians refer to as liaison: the coda of a syllable becomes the onset of the next, at least as far as stricture is concerned.

stricture

Higher stricture means that it gets articulated a bit tenser, with higher degree of approximation between articulators, a narrower groove, and with a little more air than when it is at the coda and followed by silence or by another consonant. Stricture, or the degree of constriction, reaches a brief but critical point of intensity and tension just before moving on to the vowel it precedes.

ambisyllabicity

When a consonant can be analysed as acting simultaneously as the coda of one syllable and the onset of the following syllable, as in "upper" or "button".

resyllabification

The notion of resyllabification (the process of expressing the change of linking or liaison) consists in a redistribution of the syllabic structure, so that a consonant which is part of a syllable, becomes part of another syllable instead.

The notion and its application to English is rather controversial, as everything has to do with syllabic structure in English, and therefore, we will adopt a practical approach to it. In this course, resyllabification turns into a transcription technique by which a coda consonant is transcribed as the onset of the next syllable in order to indicate an increase in the severity of its stricture. In future transcription tasks, and samples, we will use resyllabification whenever we want to indicate/register basic liaison.

epenthetic linking (linking principle)

We could establish here something of a Linking Principle: two syllabic nuclei will always be linked by means of a stricture; if this structure is not present at the phonemic level, it will be epenthetically introduced --i.e., introduced at the phonetic level.

Perhaps the simplest form of epenthetic linking is glottal linking, that happens when the two nuclei are connected by means of a glottal stop.

Glottal linking

Linking palatal approximant

Linking labial-velar approximant

Intrusive /r/ and linking /r/

assimilations

In assimilations, the change in articulation is more drastic. Through assimilation, a /t/ may be pronounced, for example, as a bilabial plosive [p]. The very definition of phoneme is challenged by this process.

According to the established theory, /t/ and /p/ are phonemes because when you replace one for the other, meaning changes: pin /pɪn/ vs. tin /tɪn/. However, in assimilation, a /t/ is substituted by a [p] or a [k] without change of meaning.

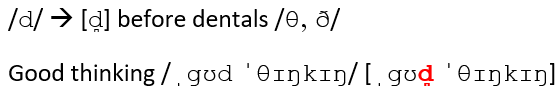

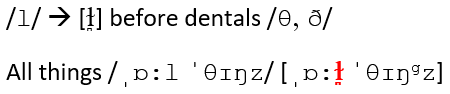

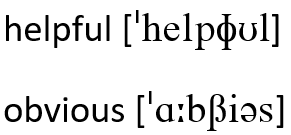

accommodations

Has to do with slight changes in the point of articulation. A frequent accommodation, for example, will involve the articulation of apico-alveolar /n/ as dental

, in order to ease the transition towards another dental, like /θ, ð/. Example: on thin air.

progressive and regressive adaptations

In articulatory adaptations, the articulation of a sound is usually transformed under the influence of another. For example, /n/ will be articulated as when it is followed by a dental consonant. In this case, the /n/ is the affected, whereas the dental is the affecting sound.

When the affected sound goes before the affecting sound, the adaptation process is said to be regressive. Most articulatory adaptations in English are regressive, but there are also a few progressive adaptations, where the affecting sound comes first, and the affected sound comes after it.

Advancing and retracting

Articulatory adaptation usually implies advancing or retracting the point of articulation.

Advancing, in general, implies an articulation that is one step nearer the outside of the oral tract. For example, the articulation of an alveolar sound is said to advance to dental.

Retracting, in general, implies an articulation that is one step further inside the mouth compared to another articulation that is taken as a point of reference. For example, in retracting a bilabial, it turns into a labio-dental. An post-alveolar articulation in English is usually the result of retracting an alveolar articulation.

dental accommodation of alveolars

The articulation of apico-alveolars affected by this process advances, and they turn into apico-dental sounds when they are immediately followed by dentals /θ, ð/. Alveolars: /t, d, s, z, n , l, r/.

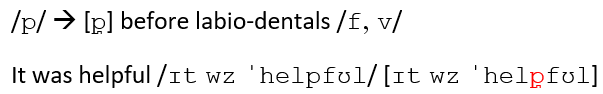

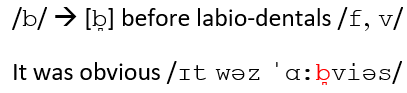

dental accommodation of bilabials

The articulation of bilabials affected by this process is retracted, and they turn into labio-dental sounds before labiodentals /f, v/.

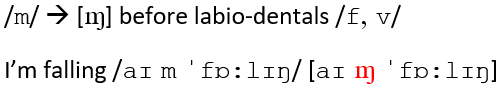

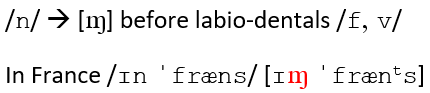

The apico-alveolar nasal /n/ often turns into labio-dental nasal [ɱ] before /f, v/.

Although less frequently, in /pf, bv/ sequences, it might also happen that instead or retracting /p, b/ to , some speakers may occasionally advance /f, v/ from dental to labial, turning them into biliabial fricatives :

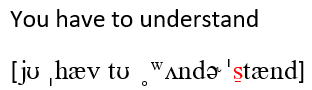

post-alveolar accommodation

The articulation of alveolar phonemes like /n, t, s, z, l/ may retract to the post-alveolar area when followed by retroflex /r/. look up the rest

Some American speakers will retract alveolar /s/ to a post-alveolar position after the rhotic vowel /ɜ:/. Although for most Americans, rhoticity does not involve strict retroflection, for those who practice a particularly intense rhoticity the /s/ in understand will acquire a distinctive retracted value:

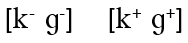

Velar plosives /k, g/ will change the point of articulation slightly, depending on what follows them. They will remain velar, but their exact point of articulation will be at a point between post-velar and pre-velar:

When followed by back vowel, or /w/, /k, g/ will be articulated further inside, around the post-velar area; and when followed by front vowel or /j/, the point of articulation will be pre-velar. Usually, you do not have to make any efforts to incorporate this behaviour; in fact, it would difficult to avoid it.

desibilantization of alveolars

Desibilantization is by no means a frequent term in English phonetics, although it is not altogether unknown either.

It could be described as the process by which a sibilant fricative is pronounced as a non-sibilant, or substituted by a homorganic non-sibilant fricative. In English we have desibilanticized alveolar fricatives as a result of the coalescence of /zð, sð/ sequences into and, respectively.

In pronuncing this phrase, we could say that /z/ and /ð/ have merged, or rather coalesced, into a voiced non-sibilant alveolar fricative, which could be represented as

The sound that we produce has features that are present in the description of both coalescing phonemes. It is alveolar like /s/, but non-sibiliant like /ð/. However, an alternative perception would propose that /z/ is elided, or almost elided, and that /ð/ undergoes retraction, and accommodates to an alveolar (although non-sibilant) articulation.

Coalescence of the of the sequence /zð/ into image above, seems to require that the alveolar be preceded by vowel (including rhotic vowels), and that the dental consonant leads to an ustressed syllable, most frequently the weak form of the, that, than.

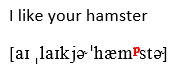

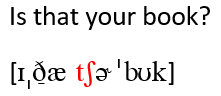

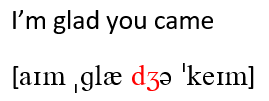

coalescence

The merging of two sounds into one that, being different from the merging sounds, also shares a number of properties with both.

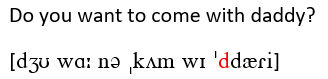

The most frequent case of coalescence in English is that of the alveolars /t, d, s, z/ immediately followed by a palatal approximant /j/ that introduces an unstressed, weak and reduced syllalbe--most often unstressed you our your. The result of this merge is a voiced or voiceless palatal-alveolar affricate /tʃ, dʒ/ in the case of /t, d/, and voiced or voiceless palatal-alveolar fricative /ʃ, ʒ/ in the case of /s, z/.

In the cases of /t, d/ however, coalescence in not the only possibility. Some American speakers prefer, always or in particular combinations, to produce weak coda plosives, with subtle realeases or even with a non-audible release, simply followed by the palatal.

anticipations

Labialization (rounding)

Lateral release of plosives

Palatalization

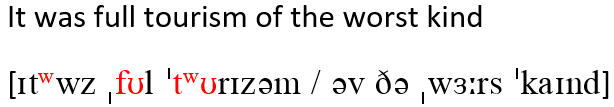

labialization (rounding)

If the lips are not involved in the articulation of a segment that is immediately followed by another segment that involves lip-rounding, the former will incorporate lip rounding. Bilabial and labio-dentals, cannot be really rounded because they involve the lower lip, but apico-dentals, alveolars, palatal-alveolars and velars will be labialized when followed immediately by rounded vowels and /w/. Some speakers labialize /ʃ, tʃ, ʒ, dʒ/ and/or /r/ in all contexts.

lateral release of plosives

We have already seen that when a plosive is immediately followed by a heterorganic stop or heterorganic nasal, this second closure is articulated during the compression of the first plosive. This is, clearly, anticipation.

When bilabial or velar plosives are followed by the lateral approximant /l/, the articulation of the approximant will also be anticipated and produced during the compression of the plosive. When the closure is undone, the /l/ is already in place and ready.

palatalization

A process where the tongue acquires a secondary articulation consisting in the approximation of the dorsum to the palate.

Palatalization involves the dorsum of the tongue. The tip of the tongue can be busy articulating an alveolar sound, and the dorsum is still free to anticipated palatals and to engage palatalization. Before palatal, /t, d, n, l/ might be pronounced, to different dregrees, as [tj, dj, nj, lj]:

Notice that palatalization turns /t, d, n, l/, pronounced as [tj, dj, nj, lj], into sounds that resemble very much other sounds we are very familiar with; basically /tʃ , dʒ, ɲ, ʎ/. It is a well-know fact, indeed, that palatalized /t, d/ have evolved into /tʃ , dʒ/ within the word, in cases like nature /'neɪtʃər/, and soldier /'soʊldʒər/. The sounds /ɲ, ʎ/ are like those we have in Spanish, in caña and gallo (not pronounced with a palatal approximant 'gayo', but with a palatal lateral approximant).

The alveolar nasal, when followed by palatal, will tend to anticipate palatalization, being pronounced as /nj/. If we push it a bit further, the palatal and the nasal will coalesce into a palatal nasal not two distant from Spanish ñ: california > califorña

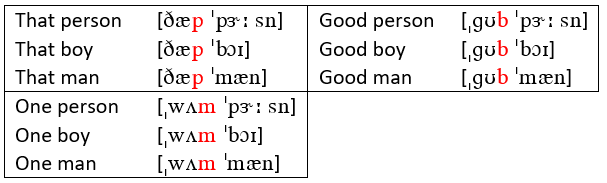

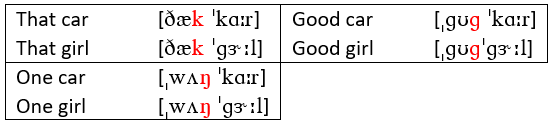

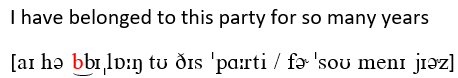

regressive assimilations

Consonants /t, d, n/ may be articulated as fully bilabial [p, b, m], and as fully velar [k, g, ŋ]. Beyond simply accommodating, we say that they assimilate to the affecting segment.

/t, d, n/ assimilate to /p, b, m/ when followed by bilabial:

/t, d, n/ assimilate to /k, g, ŋ/ when followed by velar:

Consonants /s, z/ also assimilate into /ʃ, ʒ/ when at the end of words with little or expected lexical content, followed by words that begin with /tʃ, dʒ, ʃ, ʒ, 'j/:

There are other occasional and somewhat more marginal assimilations affecting the ending of prepositions of and with, /v, ð/. In the first case, /v/ assimilates in to [b] before bilabials. When the bilabial is /m/, the /v/ might also be elided.

The auxiliar verb have, in its weak form, can display a similiar behavior:

Occasionally, /ð/ turns into /d/ and geminates with a following /d/:

progressive assimilations

The affecting sound precedes the affected sound.

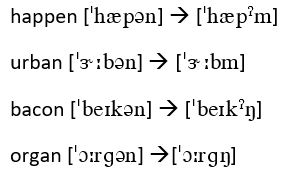

English /n/ may occasionally turn into /m, ŋ/, affected by bilabials and velars, respectively. This might happen, in fast and confident speech, in the last unstressed syllable of words, when they have a structure such as Bilabial/Velar + schwa + /n/. If the schwa is then elided, the bilabial closure can persevere into an assimilated [m], while the velar closure will do the same into [ŋ]:

Progressive assimilations after velars is somewhat more frequent.