CORE-UA 720 Impressionism, Post-Impressionism & Modernity Midterm Review

1/58

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

59 Terms

Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre, View of the Boulevard du Temple, 1839, daguerreotype

- A bustling Parisian street, but due to long exposure time (approx. 10 min), most moving objects such as carriages and pedestrians remain invisible.

- Remarkably, a stationary figure--a man having his shoe shined--was captured, making this the first photograph to include a human being.

Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre, Still Life With Plaster Casts, 1839, daguerreotype

- A life arrangement featuring casts of classical sculptures, which was a common subject in early photography due to their detailed, static nature.

- Still objects were perfect photographic subjects.

- Immobilization of the photographic subject.

Louis Jacques Mandé, Still Life With Sculpture Casts, 1839, daguerreotype

- One of the earliest surviving daguerreotypes.

- A collection of classical sculptures.

- Captures an arrangement of these casts in a way that emphasizes both the fine details and the interplay of light and shadow

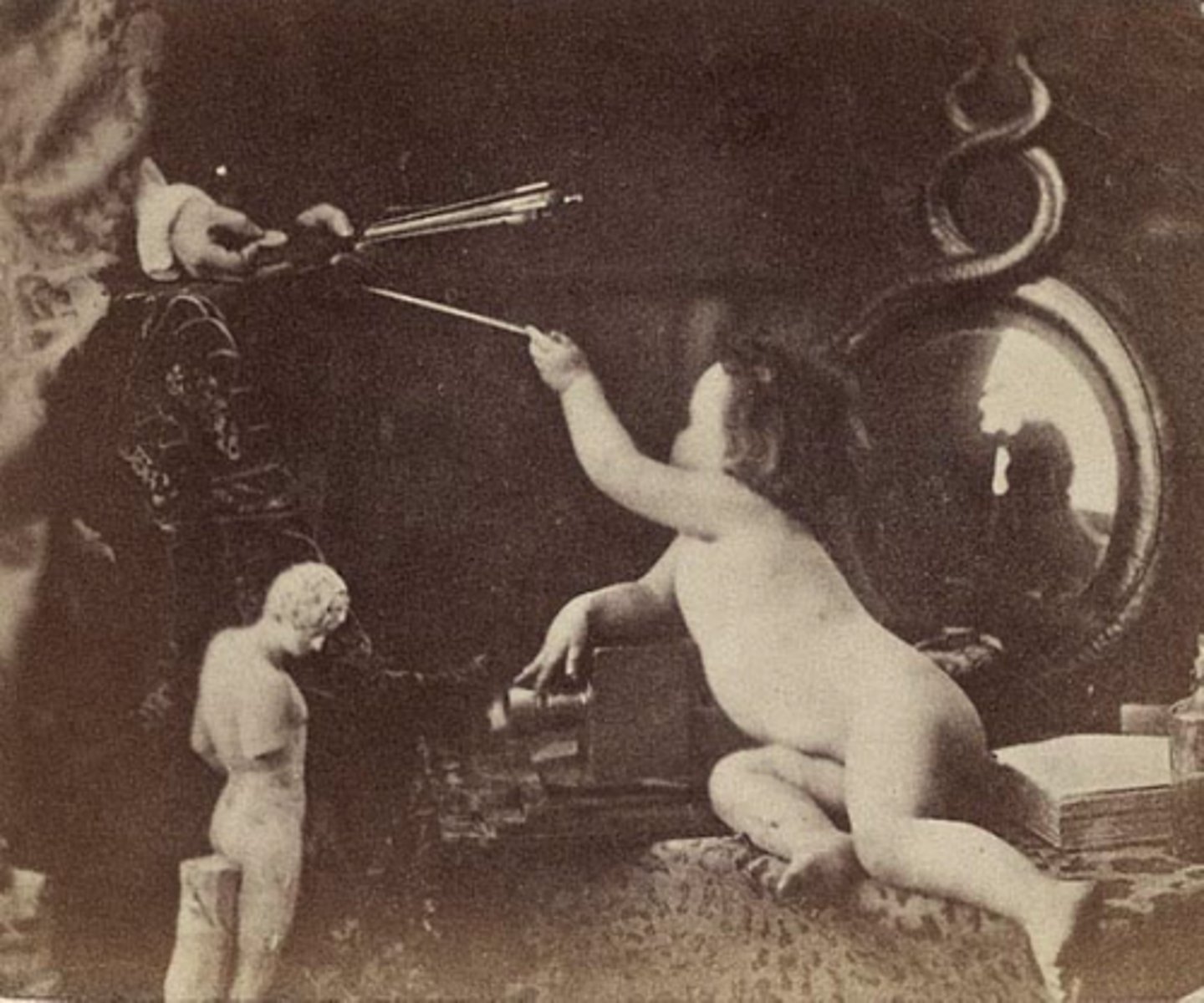

Oscar Gustavo Rejlander, The Infant Photography Giving the Painter and Additional Brush, c. 1856. Albumen silver print

- Reflects the intersection of photography and traditional art, blurring the lines between photography and fine art

- Shows a metaphorical scene where the infant represents the photography, and the painter is shown as if receiving an additional brush from the infant, symbolizing how photography was becoming a new tool or "brush" for artists

- Photography was seen as a medium that could enhance or support the painter's work, offering new ways to capture reality and inform artistic creation

- Rejlander's image also echoes the period's fascination with photography's potential in fine art, where photographers were seen as artists in their own right, sometimes collaborating with or even competing against traditional painters.

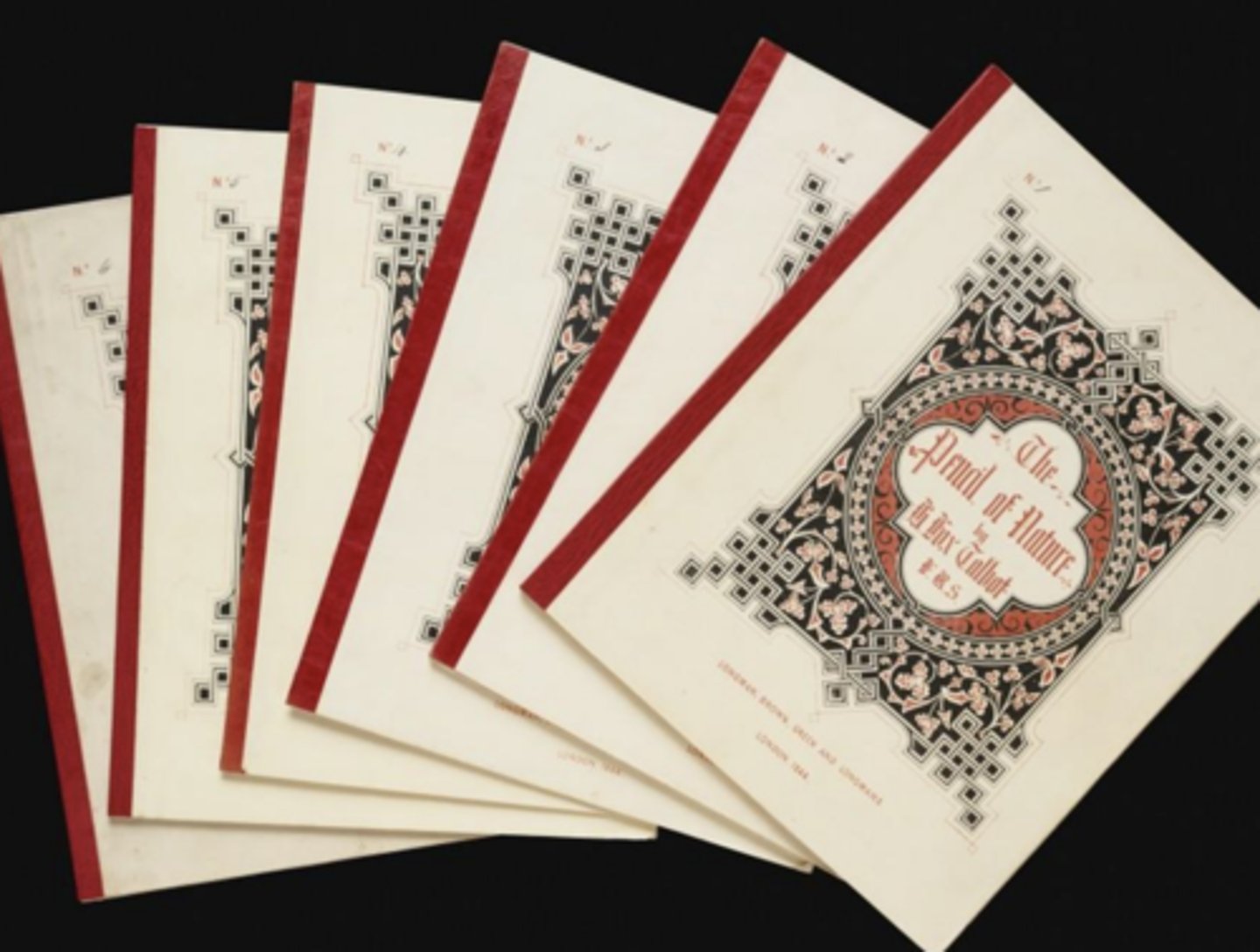

William Henry Fox Talbot, The Pencil of Nature, 1844-1846. Printed book with 24 mounted photographs--chromolithographic cover

- Talbot invented calotype—a paper-based negative-positive process, distinguishing it from the daguerreotype, which produced unique, non-reproducible images.

• The calotype was a photographic process that involved creating a paper negative, which could then be used to make multiple positive prints

- Talbot's invention was significant because it introduced the concept of reproducible photograph

- A chromolithographic cover, which was a colorful printed design that framed the idea of photography as both an art form and a scientific achievement.

- Talbot saw photography as a way to make nature "draw itself" using light-sensitive chemicals.

- "The pencil of nature" - a metaphor for the role of the hand

- The notion of rapidity, reducing the time it takes to produce images

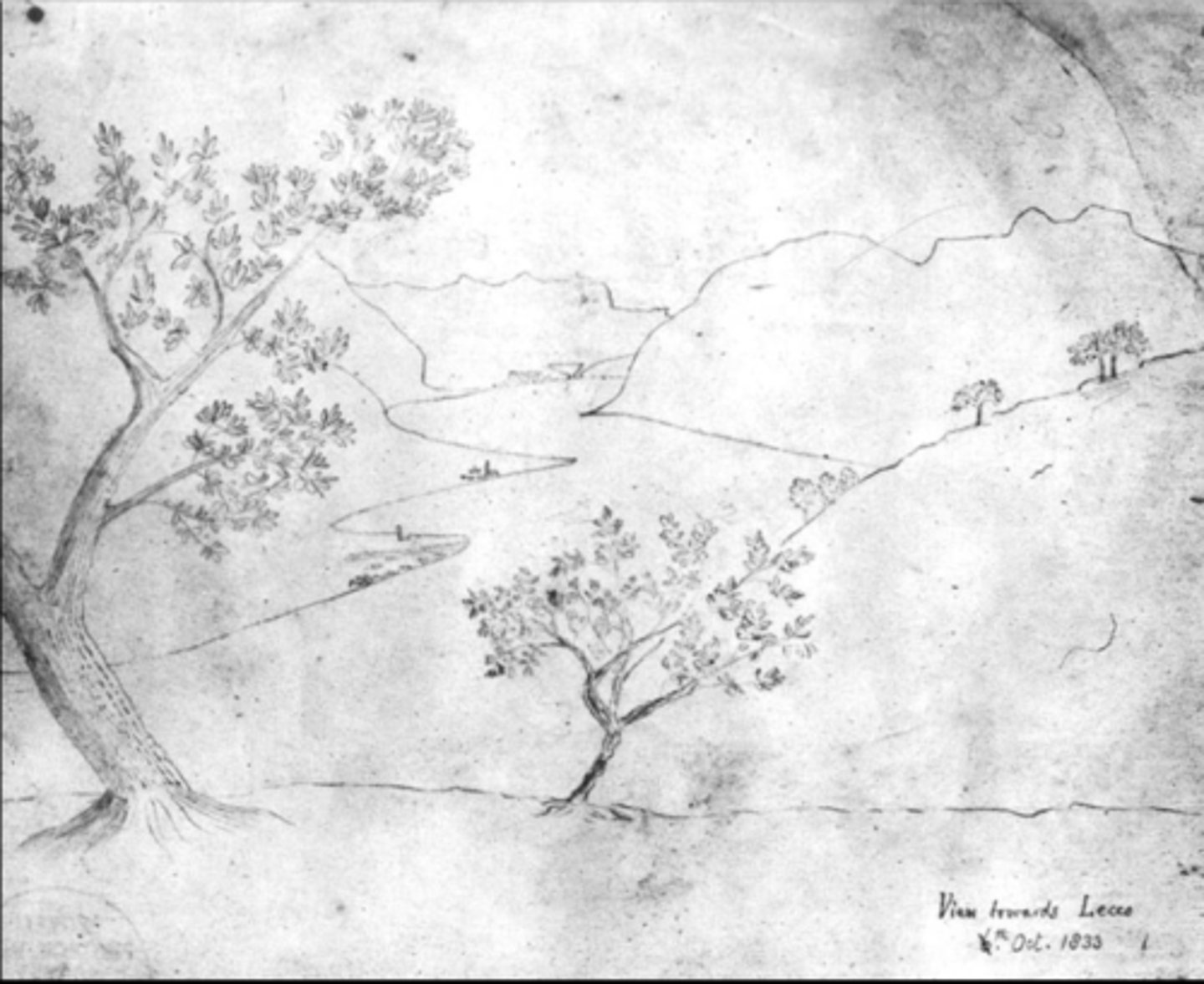

William Henry Fox Talbor, Pencil Sketch in Italy, 1833, Pencil on paper

- The use of pencil on paper in this drawing showcases Talbot's attention to detail and subtle shading, as he captured the textures and contrasts in the scene before him.

Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre, Shells and fossils, 1839, Daguerreotype Photograph

- An early example of the daguerreotype process applied to still life photography.

- Created in the same year that Daguerre introduced the daguerreotype to the public, this photograph showcases his skill in capturing intricate details with the new photographic technique.

- Fossils were a subject of fascination due to the growing scientific understanding of paleontology and the age of the Earth.

- In Shells and Fossils, the texture of the shells and the fine details of the fossils are captured with remarkable clarity.

William Henry Fox Talbot, Articles of China, 1844

Salted paper print from paper negative

- Created using the salted paper print process from a paper negative, it demonstrates Talbot's keen eye for capturing the fine details and textures of everyday objects. - The photograph's light handling, shadows, and the subtle gradations of tone provide a delicate, almost painterly effect, highlighting Talbot's artistic intent in the still life genre.

- The photograph captures the porcelain china with great attention to detail—emphasizing the smooth, reflective surfaces of the objects while also incorporating the natural light that interacts with them.

- Articles of China also speaks to the fascination with material culture in the 19th century. During this period, still life photography became a way to document and appreciate objects of everyday life, elevating the mundane to the status of art.

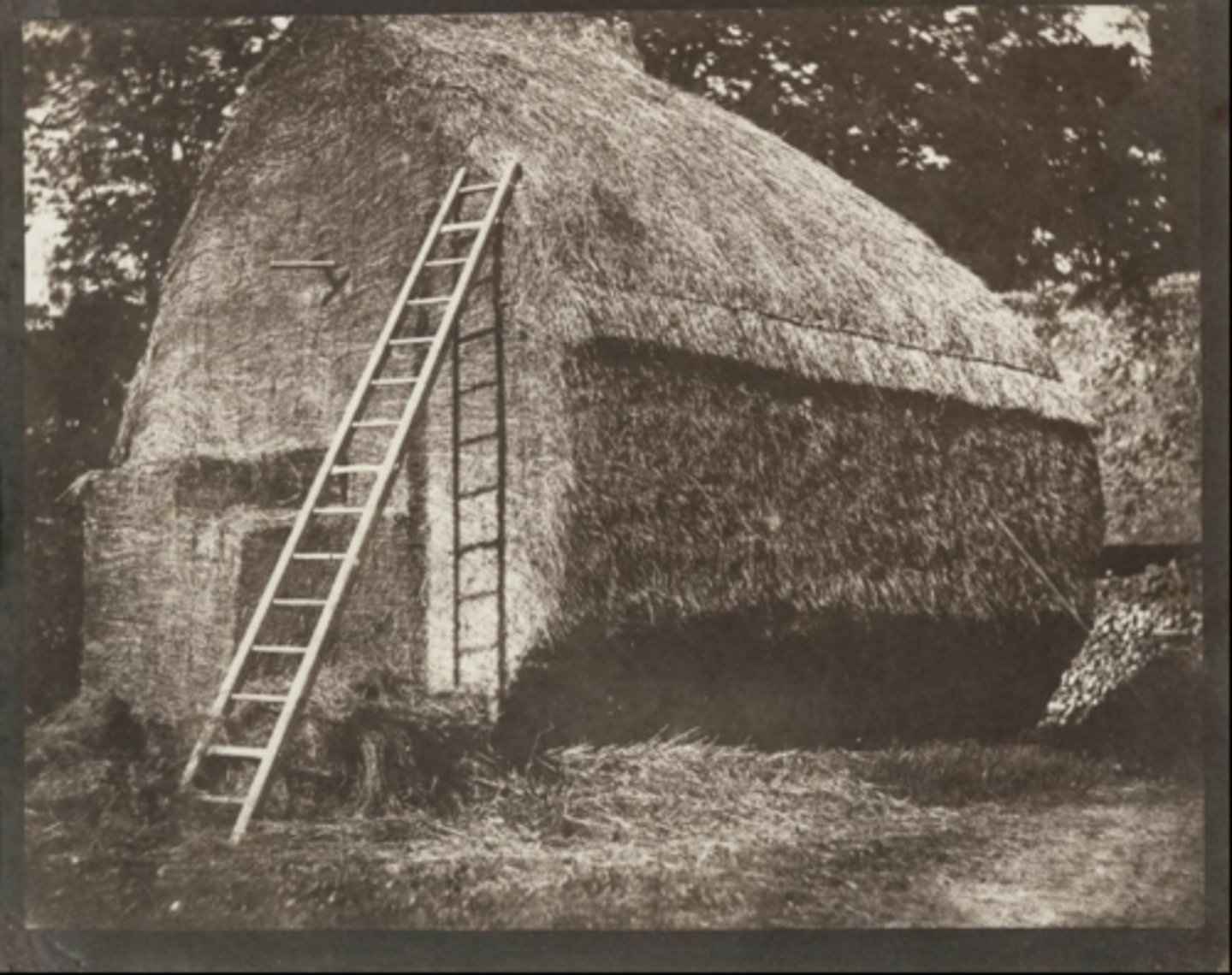

William Henry Fox Talbot, The Haystack, 1841

Salted paper print from paper negative

- Exemplifies Talbot's interest in capturing everyday scenes with a soft, almost dreamlike quality. - The calotype's characteristic grainy texture and tonal variations give the image an atmospheric depth, highlighting the contrast between light and shadow.

William Henry Fox Talbot, Entrance Gateway, Queens College, Oxford, 1843

Salted paper print from paper negative

- Talbot states not noticing the clock in the image until many years later. The uncanny aspect of this is taking a photo and not realizing its contents raises a question of automatism or photography, which supersede human agency and intention, even if the photo making machine is human

- Rapidity is important because it highlights the ability to unconsciously produce images.

- Photography as a key thought process to approaching fine art impressionism.

Benjamin Brecknell Turner, Crystal Palace, Transept, 1852 Salted paper print from paper negative

- Greenhouse designer Joseph Paxton in 1851

- Modular structure built from glass, can be taken apart and put together

- Reflects the mid-19th century fascination with progress, industry, and modernity

- The Great Exhibition was a global event, attracting crowds from around the world. It displayed industrial achievements, including steam engines, textiles, and scientific instruments, celebrating technological progress. The exhibition was a stage for Britain's industrial dominance and an opportunity for nations to showcase their own advancements.

- Domestication of Nature - The Crystal Palace itself symbolizes the taming of nature through industrial advancements.

Constantin Guys, Meeting in the Park, Ca. 1860

Pen, ink and watercolor on paper

- A media incorporating sketch and watercolor. Pen and ink provides a sense of immediacy, while watercolor softens the scene.

- The park setting suggests a space of leisure and sociability, where individuals of the bourgeoisie gathered.

- The faces of the people are somewhat unrecognizable.

Constantin Guys, La Presse, ca. 1850-1860

Pen, ink and watercolor on paper

- An intersection of early journalistic illustration and fine art.

- La Presse was one of the first daily newspapers to include illustrated stories, and Guys was a key figure in this development.

- The pen, ink, and watercolor technique allowed him to quickly capture fleeting moments, adding an element of immediacy to his illustrations.

Edouard Manet, Olympia, 1863. Oil on canvas

- Olympia caused an uproar when it was first exhibited at the 1865 Salon in Paris.

- This painting portrays a nude woman reclining on a bed, gazing at the viewer with a direct and confident stare.

- Unlike Titian's Venus of Urbino, which idealizes and softens the female form, Manet's Olympia is strikingly modern and confrontational.

- The model, Victorine Meurent, is not depicted as a goddess, but as a real woman, and her gaze is unashamedly direct, challenging the viewer's expectations.

- The casualness of the pose, the flatness of the brushstrokes, and the stark lighting created a sense of realism that was in stark contrast to the more idealized nudes that had preceded it.

- Manet's depiction of the female nude was controversial because it stripped away the idealism that had traditionally been associated with such representations and instead presented a more raw, modern version of femininity.

Gustave Caillebotte, Boulevard Haussmann, effect of snow, 1880. Oil on canvas

- Captures a wintry Parisian scene, emphasizing the transformation of the city under Haussmann's renovations and the ephemeral effects of snow.

- This quietness, combined with the distant perspective, creates a sense of detachment, reflecting the solitary experience of observing the city from above.

- The muted color palette, dominated by whites, grays, and soft blues, conveys the quiet stillness of a snowy day.

Édouard Manet, Music in the Tuileries, 1862, oil on canvas

- The painting captures the growing urban leisure culture of the Second Empire under Napoleon III, where public parks became spaces for social interaction.

- The scene is dynamic yet fragmented, with loosely defined figures conveying movement and the fleeting nature of modern life.

- It presents a bourgeois gathering, where men and women of the upper class are dressed elegantly, engaging in conversation rather than focusing on the music itself.

- Unlike traditional history painting with clear outlines and polished surfaces, Manet uses loose, quick brushstrokes, emphasizing spontaneity and immediacy.

- The figures blend into one another, creating a sense of crowded intimacy, mirroring the fleeting moments of real-life experience.

- The trees and dappled sunlight break up the composition, reinforcing the impression of a lively, naturalistic scene rather than a staged or idealized one.

- Manet included himself (with a beard) on the left side of the painting, subtly inserting the artist into the social world he was portraying.

- Baudelaire's concept of the flâneur (the detached urban observer) is embodied in this painting—Manet captures the ephemeral experience of city life, rather than an idealized or moralizing scene.

- Unlike historical paintings that clearly defined class and status, Manet's work suggests a more democratic, modern crowd, where aristocrats, intellectuals, and ordinary Parisians mix together.

Édouard Manet, Boy with Cherries, 1859, oil on canvas

- The boy, likely a street vendor or servant, is dressed in simple, slightly oversized clothing, emphasizing his lower social status.

- His direct gaze and confident yet casual pose create a sense of quiet realism and psychological depth.

- He holds a small basket of cherries, which are painted with striking detail, contrasting with his dark clothing and the muted background.

- The loose yet controlled brushstrokes and the play of light and shadow on the boy's face reflect this inspiration (strong contrast of light and dark).

- Instead of depicting an aristocrat or mythological figure, Manet gives artistic attention to a working-class boy, suggesting a democratization of portraiture.

- Cherries often symbolize youth, sensuality, or fleeting pleasure, which could be a subtle commentary on the boy's transitory stage in life.

- The act of offering or holding fruit has historical art associations with temptation or economic labor—the boy may be selling cherries, reinforcing his connection to labor and survival.

Édouard Manet, Portrait of Victorine Meurent, 1862

Oil on canvas

- The portrait is a half-length depiction, focusing on Meurent's direct gaze and strong presence rather than idealized beauty.

- Manet employs chiaroscuro light and shadow contrast, yet with a looseness that prefigures Impressionism.

- Victorine wears a simple yet elegant blue-gray jacket with a fur collar, suggesting a mix of bourgeois sophistication and bohemian independence.

- The loose brushwork, particularly in her hair and clothing, reflects Manet's shift away from highly finished academic painting.

- Unlike conventional 19th-century portraits of women, which often emphasized passivity or demureness, Meurent's expression is self-assured, direct, and even slightly challenging.

- There is a subtle ambiguity in her gaze—she is neither entirely inviting nor distant, creating an enigmatic quality. This suggests that Manet was portraying Victorine as a real individual rather than a decorative object, which was unusual for female portraits of the time.

Victorine Meurent, Self-Portrait, ca. 1876

Oil on canvas

• Victorine Meurent's Self-Portrait challenges her historical perception as merely Édouard Manet's model, instead revealing her artistic talent and self-representation.

• Unlike the passive or objectified female figures she embodied in Manet's paintings, Meurent presents herself as a serious and independent artist. She gazes directly at the viewer with confidence, suggesting self-awareness and professional ambition. Her pose and attire are modest yet assertive, with none of the sensuality often imposed upon her by male artists.

• Meurent's attention to detail, form, and light

• The controlled handling of the face, hair, and clothing reflects a refined, traditional technique, setting her apart from the experimental style of her former mentor.

Manet, Portrait of Laure, 1862, oil on canvas

• Laure was a Black model who posed for Édouard Manet in Olympia (1863) and other works, but very little is known about her life.

• She is depicted in Olympia as the maid bringing a bouquet of flowers to the reclining nude

• Laure's presence in Olympia is significant because it reflects France's colonial connections with Africa and the Caribbean. Her depiction aligns with a long tradition of exoticized representations of Black women in Western art, yet she is also more individualized compared to earlier stereotypes.

• Unlike earlier European paintings where Black figures were purely decorative or submissive, Laure's presence in Olympia is more ambiguous. Her gaze is directed at the viewer, possibly challenging the social dynamics of race and servitude.

• Art historians such as Denise Murrell have argued that Laure should not be seen as just an accessory in Olympia, but rather as an active figure in the painting's modernity.

• She may also have posed for Manet's Children in the Tuileries Gardens (1861) and La Négresse (1862), though definitive evidence is lacking.

Manet, Children in the Tuileries Gardens, ca. 1861-1862, Oil on canvas

• Unlike academic painters of the time, Manet uses a light, almost sketch-like approach, foreshadowing Impressionist techniques.

• The painting has a soft, atmospheric quality, with earthy tones and delicate lighting reminiscent of Velázquez.

• The composition focuses on ordinary moments of childhood, reinforcing Manet's fascination with modern life rather than idealized, historical themes.

• The Tuileries Gardens were a popular social gathering spot in Haussmann's Paris, reflecting the transformation of the city into a space for both elite and everyday citizens.

• Music in the Tuileries highlights upper-class figures and intellectuals, whereas Children in the Tuileries Gardens captures a more intimate, casual moment.

• This painting is softer and more intimate, while Music in the Tuileries has bolder contrasts and sharper edges, marking Manet's shift toward a more experimental approach.

Édouard Manet, Dejeuner sur l'herbe, 1863. Oil on canvas

Édouard Manet, Luncheon in the Grass, 1863. Oil on canvas

• The painting depicts a picnic scene in a lush, outdoor setting, with a nude woman casually sitting alongside two fully clothed men.

• The woman stares directly at the viewer, a striking feature that contributes to the provocative nature of the painting.

• The contrast between the formal attire of the men and the nakedness of the woman challenged traditional depictions of the female nude in art, which were often idealized and associated with mythology or classical themes.

• A woman in the background who is partially dressed, sitting or kneeling in the distance. She is not as prominently featured as the nude woman in the foreground, but her presence adds a layer of complexity to the composition.

• The contrast between her and the nude woman in the foreground adds an element of narrative tension to the scene. Some interpretations suggest that she might represent a symbol of modesty or virtue, contrasting with the boldness of the naked woman, while others see her as simply part of the broader social setting of the picnic.

Manet, The Battle of the Kearsarge and the Alabama (1864), Oil on Canvas

• Captures a pivotal moment in the American Civil War—the naval battle between the USS Kearsarge and the CSS Alabama off the coast of Cherbourg, France, on June 19, 1864.

• Manet, though French, was fascinated by contemporary events, particularly naval warfare. This work reflects his engagement with modernity and interest in depicting real-world action.

• The painting presents the battle from a distance, showing smoke rising from the sinking Alabama, with the victorious Kearsarge nearby.

• Manet employs loose, expressive brushstrokes, moving away from the hyper-detailed precision typical of traditional history painting.

• The sea dominates the canvas, with its deep blues and turbulent waves, emphasizing movement and drama.

• The contrast between thick, dark smoke and the bright sky heightens the sense of destruction and loss.

• Even though Manet uses oil painting, a slow method, he still implements what's considered a fast method, painting from memory

Claude Monet, Poppy Field near Argenteuil, 1873, Oil on canvas

• A quintessential impressionist painting that encapsulates the problematic that the way in which landscape can not be distinguished from human figures

• The figure being a secondary in the painting

• Blurred absence of face and body

• Manet's figures possess a 'facingness' while Monet's figures typically neither look at the painter nor engaging with the audience.

• The painting depicts a vast field of red poppies, with a mother and child pair strolling through the foreground and another pair in the distance.

• The rolling landscape, bright summer sky, and scattered wildflowers create a serene, dreamlike quality.

• Monet's wife, Camille, and their son Jean are believed to be the figures in the foreground, reinforcing the intimacy of the scene.

• The winding path and receding line of poppies create a sense of depth, guiding the viewer's eye into the scene

• The figures become smaller in the background, reinforcing the vastness of the landscape.

• The soft, hazy brushstrokes suggest movement, as if the wind is gently swaying the flowers.

• The figures blend into the landscape, reinforcing harmony between people and the environment.

• Reflects the Impressionist fascination with everyday scenes rather than grand historical subjects.

Claude Monet, Luncheon on the Grass (1865-66), Oil on Canvas (Unfinished)

• The scene is set in a lush, outdoor setting, with a group of figures gathered around a table, seemingly preparing for a meal or conversation.

• The landscape and soft, warm light suggest a peaceful rural scene, likely based on Monet's own love for nature and leisure activities.

• The scene is set in a lush, outdoor setting, with a group of figures gathered around a table, seemingly preparing for a meal or conversation.

• The landscape and soft, warm light suggest a peaceful rural scene, likely based on Monet's own love for nature and leisure activities.

• The lack of detailing in the figures, especially their faces, suggests that Monet was more concerned with light, color contrasts, and the overall composition.

• Monet's work has softer, more natural brushwork and focuses more on light, while Manet's is highly staged and controversial in its nude depiction.

Claude Monet, Woman in Green Dress, 1866. Oil on canvas,

• The painting features a woman in a green dress, seated in a naturalistic and relaxed pose.

• The woman is positioned in the foreground, with a plain background, likely meant to focus the viewer's attention on her figure, while the use of rich color emphasizes the fabric and texture of her dress.

• The model is not idealized but instead depicted in a manner that aligns more with the Impressionist approach of portraying figures in natural settings with a sense of spontaneity.

• The woman's posture and relaxed nature are characteristic of Monet's interest in everyday scenes and modern life.

• Monet's style is soft, painterly, and fluid, with little emphasis on fine details in the face or figure. The background is muted, focusing primarily on the woman and her vibrant dress.

Édouard Manet, Young Woman in 1866, 1866. Oil on canvas.

• Like Monet, Manet also depicts a woman, but in this case, the subject is more formalized in comparison to the relaxed tone of Monet's painting.

• The woman in this painting is seated in a similar manner, but her face and figure are more defined and stylized, giving her a more constructed presence.

• Manet's woman is dressed in a light-colored, contemporary gown, and her gaze is directed directly at the viewer. The figure appears posed, with an elegance that speaks to the academic tradition but with a more modern twist.

• Manet's brushwork is more deliberate and precise than Monet's. The lines are clearer, particularly in the detailing of the woman's figure and face.

• The contrast between light and dark is more stark in Manet's painting, and there's a stronger emphasis on formality and compositional clarity than the spontaneous, fleeting qualities of Monet's work.

Claude Monet, The Luncheon, 1868-9. Oil on canvas

• This painting features a private scene of Monet's family during a meal.

• The painting was initially rejected by the Salon in 1870 but later shown at the first Impressionist exhibition.

• Its monumental size elevates an everyday moment to that of a historical painting.

• It depicts Monet's wife Camille, their son, and a maidservant, showcasing the artist's early approach to leisure and domestic life.

• The light plays a central role, gently illuminating the scene and creating a soft, almost dreamlike effect, blurring the boundaries between the figures and the surroundings.

Claude Monet, Train in the Countryside, sunrise, ca. 1870, Oil on canvas.

• Depicts the port of Le Havre at sunrise, with the sun's reflection on the water.

• Sunrise is a hallmark of Monet's evolving style and a cornerstone of Impressionism. The painting broke away from the detailed, precise representation of landscapes, instead offering a more emotional, momentary view of the world.

• Monet's exploration of light and color over precise form captures the spirit of a new artistic vision, marking a revolutionary departure from the academic art traditions of the time.

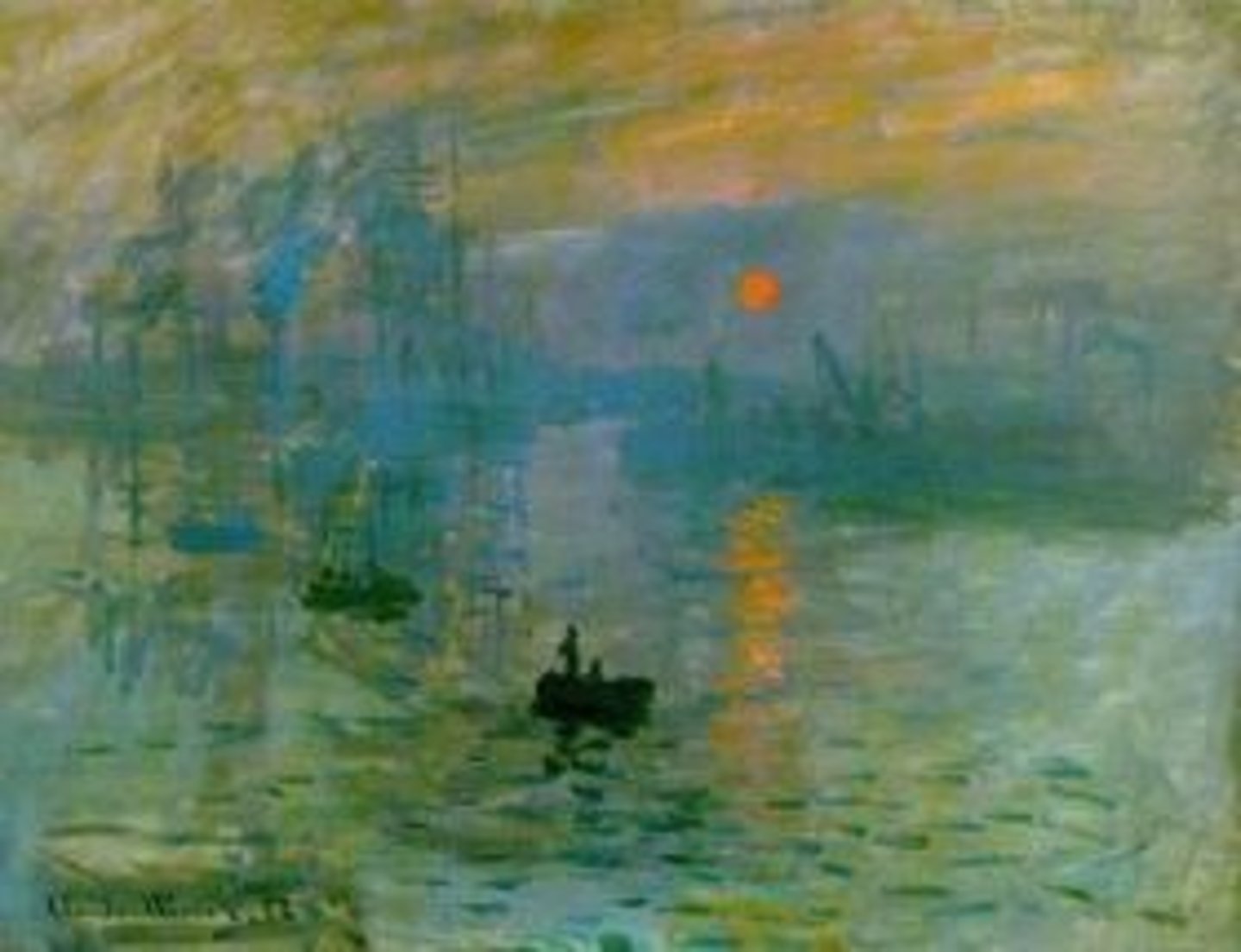

Claude Monet, Impression, sunrise, 1872. Oil on canvas.

• Depicts the harbor of Le Havre at sunrise. The scene is painted with loose brushstrokes capturing light and water rather than specific details. The sun reflects off the water, creating a hazy, almost abstract scene.

• The dominant colors are oranges, blues, and grays, emphasizing the transition of light at dawn.

• Monet pushes the boundaries of traditional landscape painting by using vibrant colors to evoke the feeling of sunrise.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Nocturne in Grey and Gold: Chelsea Snow (1876), Oil on Canvas

• Focuses on the effects of light and color at night.

• In this painting, a quiet, subdued atmosphere is achieved through muted tones of grey and gold, showcasing Whistler's ability to capture the feeling of a scene rather than its precise details.

• The piece explores mood and emotion, drawing attention to the harmony of color and light, offering a serene, almost abstract view of the Chelsea neighborhood in London.

• Both Monet and Whistler use color and light as key elements, but Monet captures a vibrant sunrise while Whistler evokes a somber, nocturnal scene.

• Monet's work has greater movement with broad strokes, while Whistler's is more subdued and refined with subtle tonal shifts.

• Both paintings emphasize impression over accurate representation, but Monet's work is more dynamic and representational in comparison to Whistler's abstracted mood.

Édouard Manet, Monet in His Studio Boat, 1874. Oil on Canvas

• Manet's painting shows Monet seated on his studio boat, along the banks of the Seine River.

• Manet's use of color in this painting, much like Monet's, focuses on natural tones and the effects of light. The reflections on the water are a primary feature, highlighting Monet's characteristic interest in how light plays across surfaces. The vivid colors of the sky, water, and boat contrast with the darker tones of Monet's figure, drawing attention to his role as the observer and creator. The blending of hues, particularly the reflections of the boat and sky, reinforces the Impressionist theme of capturing transient moments in nature.

• The loose brushwork in Monet in His Studio Boat echoes the techniques Monet was known for during this period.

Camille Pissarro, The Artist's Palette with a Landscape, c., 1878-80, oil on panel

• Unlike conventional paintings, this work is painted directly onto an artist's palette, making it a rare example of an artwork that integrates both the process and the product of painting.

• The palette retains its original shape, complete with a thumbhole, reinforcing the idea that this piece is an extension of the creative process rather than a traditional composition.

• The application of color is dynamic, with dabs of green, blue, and earthy tones blending together in a way that suggests movement and depth. The

• The juxtaposition of warm and cool tones gives the painting depth, with the sky's soft blues and whites creating contrast against the lush greens and browns of the land.

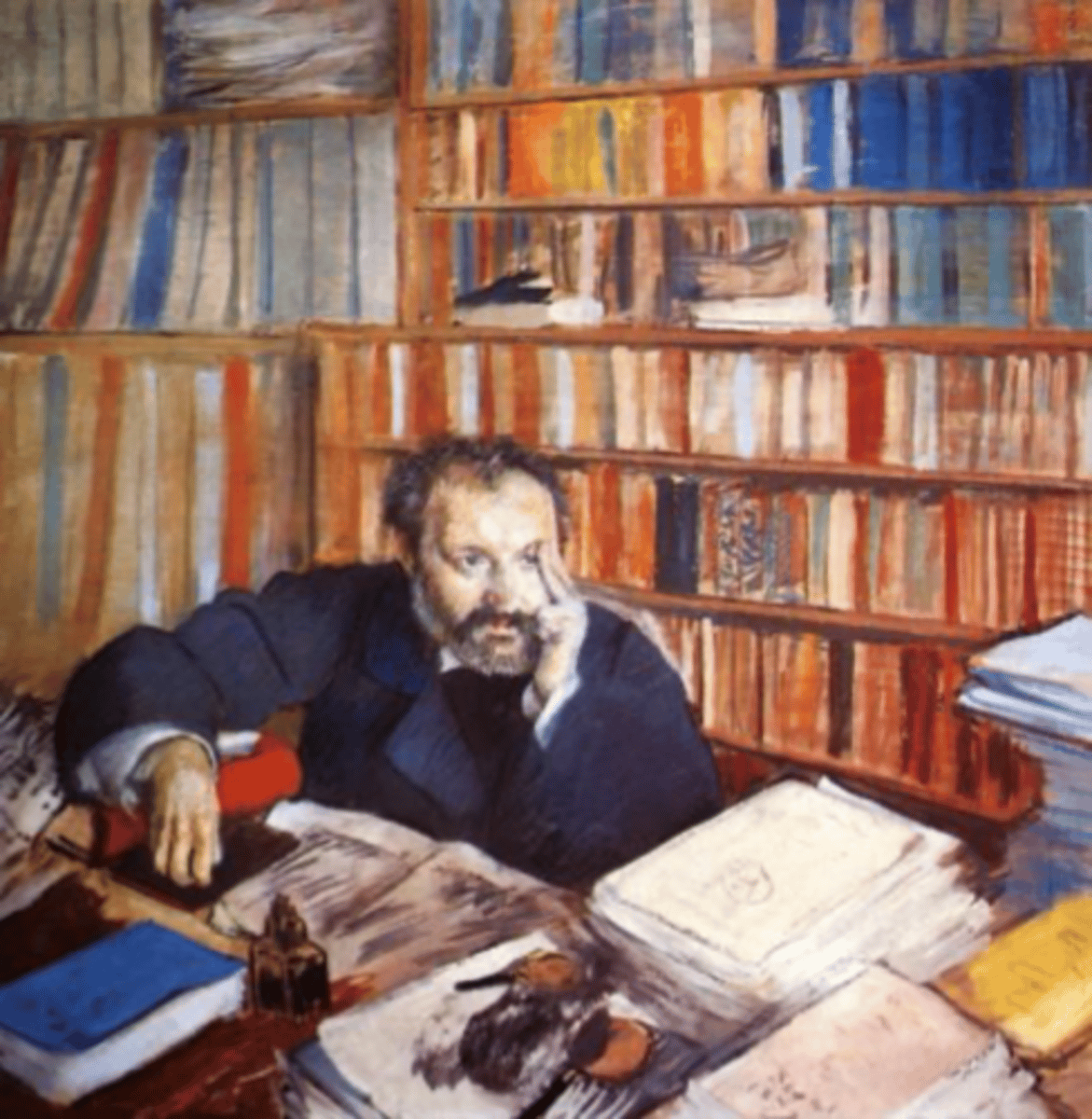

Edgar Degas, Portrait of Edmond Durant, 1879. Pastel and tempera on paper

• Degas presents Duranty in a three-quarter view, seated in a relaxed yet slightly tense posture. His body leans forward, and his hands rest in his lap, conveying a sense of introspection or engagement in thought.

• The background is minimalistic, directing attention to Duranty himself, yet the space around him is carefully composed to create a sense of depth. The diagonal positioning of his body adds a dynamic quality to an otherwise still and contemplative scene.

• Duranty was an important literary figure and a close associate of Degas and the Impressionists. His writings often defended the naturalistic representation of modern life, which aligns with Degas' own artistic interests. The portrait, therefore, is not just a depiction of an individual but a reflection of a shared artistic ideology.

• Duranty's gaze is slightly averted, his expression pensive and serious. Degas captures not just the physical likeness of his subject but also a sense of his intellect and introspection.

• The slightly slumped posture and downward glance suggest deep thought, perhaps even melancholy. This introspective quality distinguishes Degas' portraiture from more traditional, formal depictions of the time.

Claude Monet, Camille on her Deathbed, 1879. Oil on canvas

• Claude Monet painted Camille on Her Deathbed in 1879, capturing the final moments of his first wife, Camille.

• The painting is deeply personal and stands apart from Monet's usual focus on light, landscapes, and color.

• Monet became fixated on the shifting colors of her face as she passed, an observation that reflects both his grief and his artistic obsession with light and color.

Édouard Manet, The Laundry, 1875. Oil on canvas

• This painting is part of Manet's ongoing fascination with everyday scenes of working-class life in Paris.

• The subject—woman engaged in laundry work—reflects the realities of urban labor, a theme also explored by Impressionists like Degas and Pissarro.

• The painting depicts two women engaged in laundry, one seated and seemingly resting while the other is actively working.

• Manet employs a muted yet naturalistic palette, with whites, grays, and soft earth tones dominating the composition.

• The contrast between light and shadow adds depth, emphasizing the texture of the fabrics and the worn appearance of the women's clothing.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Pond with Ducks in Autumn, 1873. Oil on canvas.

• The falling leaves and the presence of the ducks in the water evoke a sense of change and transition.

• The use of light plays a central role, with the reflections of the autumn foliage on the surface of the water.

• The ducks in the water add life to the scene, giving a sense of movement amidst the stillness of the landscape. The painting seems to invite the viewer into a calm, contemplative moment in nature, characteristic of Renoir's style during the early Impressionist period.

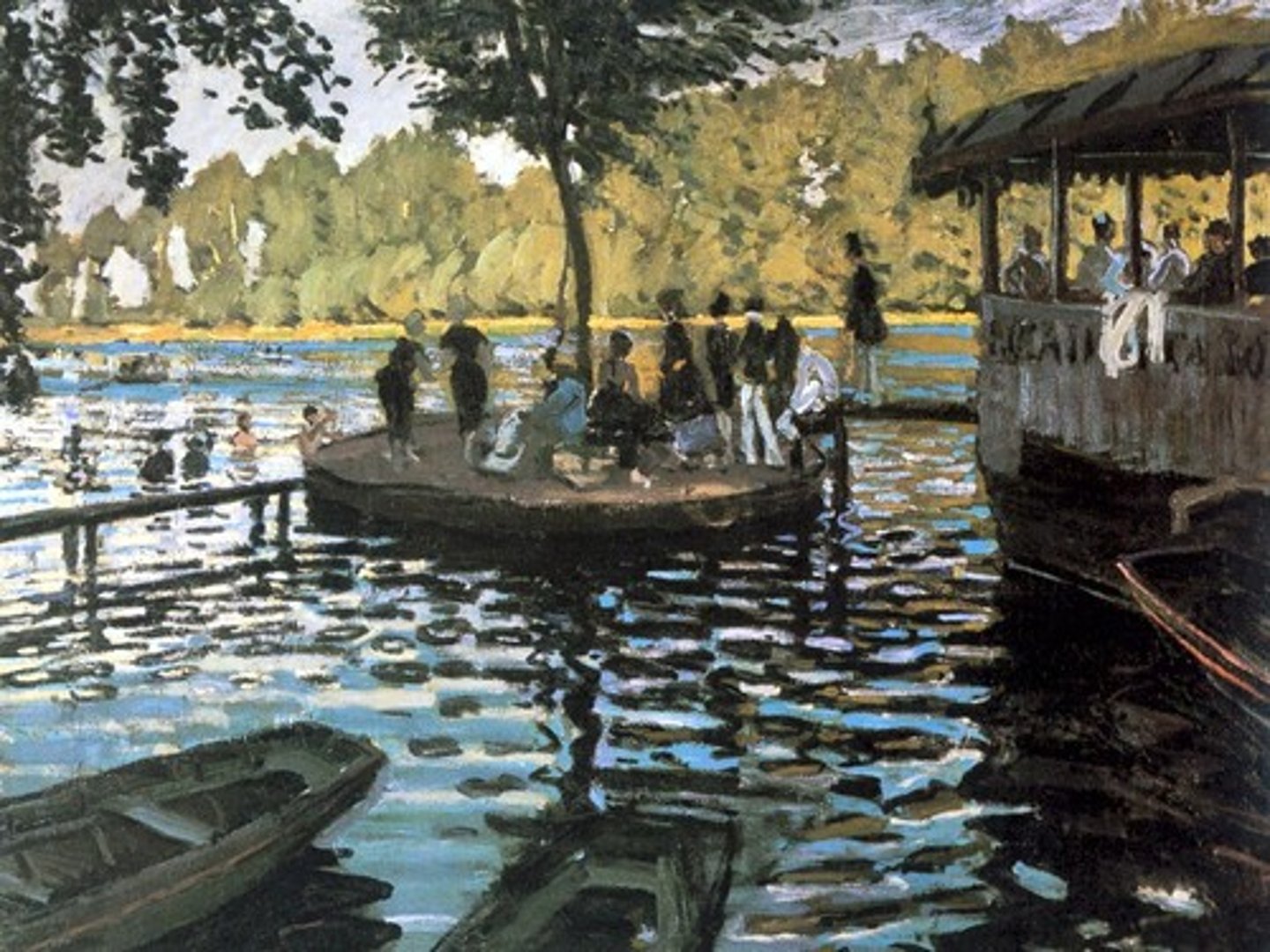

Claude Monet, La Grenouillère, 1869. Oil on canvas.

• Depicts a popular riverside leisure spot along the Seine River, near Paris, at a place called La Grenouillère (meaning "The Frog Pond"), where Parisians went to relax, socialize, and enjoy the natural surroundings.

• The brushstrokes are quick and vibrant, creating a sense of immediacy and capturing the dynamic qualities of the scene.

• The water is alive with reflections, showing Monet's early exploration of how light interacts with surfaces, a theme that would dominate his later work on water lilies and reflections.

Claude Monet, Gare Saint-Lazare, Seen from the Pont de l'Europe, 1877, oil on canvas

• Claude Monet painted The Pont de l'Europe, Gare Saint-Lazare in 1877 as part of his series on the Gare Saint-Lazare railway station in Paris.

• Captures the modernization of Paris.

• The painting showcases the Pont de l'Europe (Europe Bridge), a large iron bridge near the Gare Saint-Lazare, one of the busiest railway hubs in Paris.

• A train is arriving or departing, surrounded by thick clouds of steam and smoke, which blend into the sky.

• In the background, we see the industrial architecture of the station, including iron structures and glass roofs, creating a sense of depth.

• The steam and smoke diffuse the light, softening the hard edges of the train and buildings.

• Monet uses a mix of blues, grays, and whites to convey the cool tones of metal and smoke.

• Warmer tones, such as ochres and oranges, appear subtly in the background, adding depth.

Claude Monet, The Gare Saint-Lazare, 1877, oil on canvas

• A wider view of the railway station, focusing on the architecture, tracks, and atmosphere rather than human figures.

• Steam from the locomotives fills the space, partially obscuring the iron-and-glass structure of the station.

• Monet captures the diffusion of light through smoke, a key theme in Impressionism.

• The palette consists of soft blues, grays, and whites, emphasizing the ethereal effect of steam and light.

Claude Monet, Exterior of the Gare Saint Lazare: The Signal, 1877, oil on canvas

• Monet's depiction of the Gare Saint-Lazare reflects the transformative period in Parisian history, marked by the rise of the railway system, which was crucial to the city's industrialization.

• The smoke billowing from the trains blends with the atmosphere, and the structure of the station, with its iron framework, appears to dissolve into the mist.

Claude Monet, Rouen Cathedral, West Façade, Sunlight, 1894. Oil on canvas

• Each painting in the series explores the changing light throughout the day, capturing the façade of the cathedral under various lighting conditions and at different times. This one captures the cathedral in bright, direct sunlight, emphasizing the play of light on the intricate stonework and the dynamic interplay of color and texture.

• Rather than depicting the exact architectural features of the cathedral, Monet is more concerned with capturing the effect of light on its surface. The play of sunlight on the stone creates subtle shifts in color and tone, giving the building a vibrant, almost fluid appearance.

Claude Monet, Branch of the Seine near Giverny (Mist), oil on canvas, 1897.

• The mist that envelops the scene softens the entire landscape, blurring the boundaries between land, water, and sky.

• The colors are subdued and muted, creating an almost ethereal effect, as if the viewer is looking at a scene through a veil of fog.

• Monet's brushstrokes are loose and fluid, allowing the mist to blend seamlessly with the water and trees. The light is diffused, and there are subtle reflections of the surrounding landscape on the water's surface.

Gustave Caillebotte Young Man at His Window, 1876 Oil on Canvas

• Shows a young man gazing out of a window, framed by the architectural elements of the building.

• The view from the window is composed with careful attention to the geometry of the urban landscape. The lines of the balcony, windows, and walls are sharply defined, and the angle of the window creates a strong sense of depth.

• The viewer is placed in a position where they are almost peering into the scene, as if they are standing at the same distance from the window as the subject.

• The figure of the young man appears detached and contemplative, his gaze directed outwards, but the exact focus of his attention is not clear. This creates a sense of introspection, as if he is observing something beyond the frame, yet the painting also invites viewers to reflect on his position within the modern city.

Gustave Caillebotte, Paris Street, Rainy Day, 1877. Oil on canvas

• Caillebotte's use of perspective is striking: the view is taken from a slightly elevated position, creating a sharp, almost photographic realism that draws attention to the architecture, the figures, and the reflections on the wet street.

• The large street, with its grand scale and newly designed layout, symbolizes the modern city, while the people walking through it in the rain suggest the lives of ordinary Parisians navigating this transformed environment.

• The figures are elegantly dressed, indicating that Caillebotte is capturing a moment of middle and upper-class Parisian life.

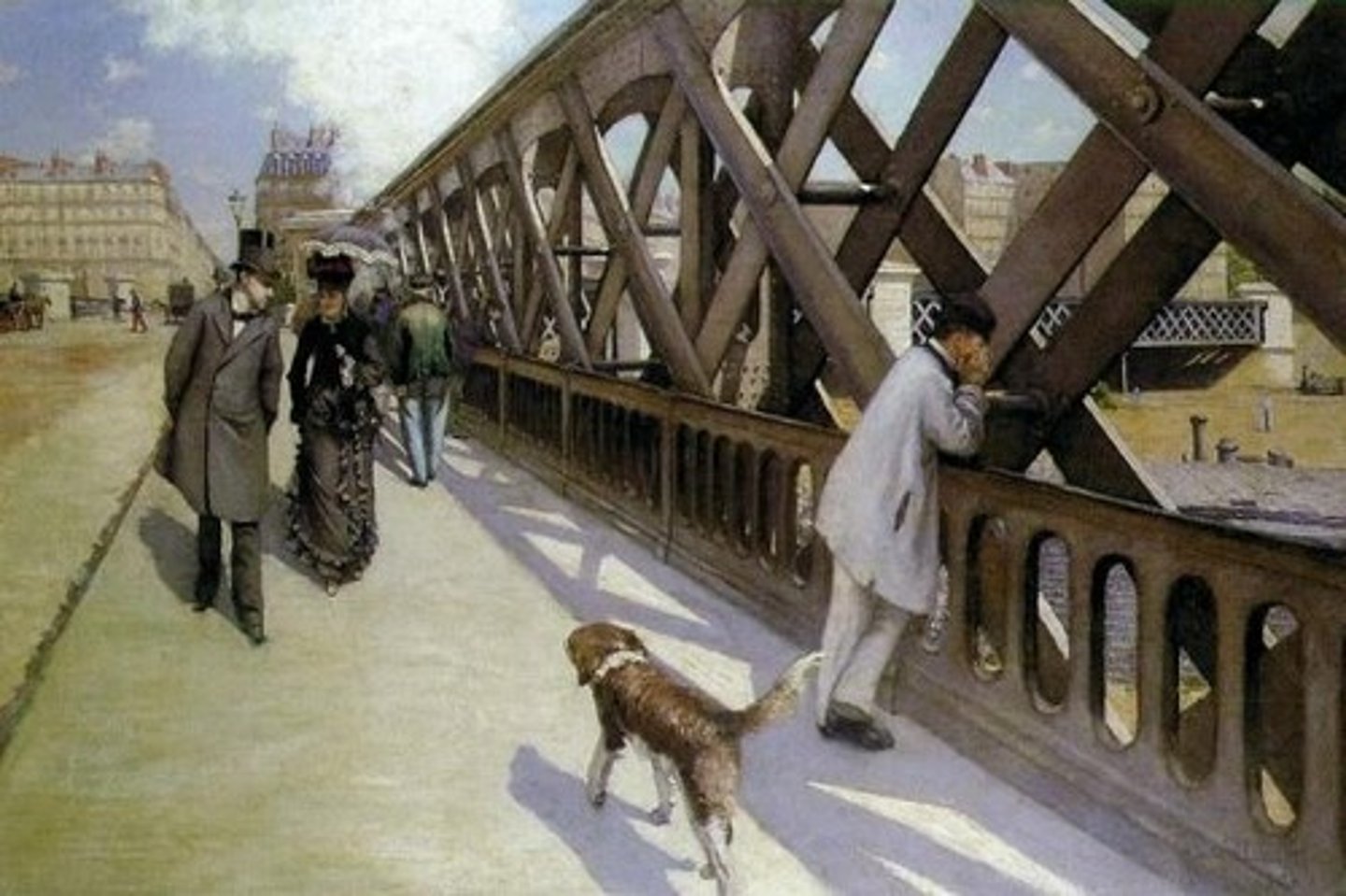

Gustave Caillebotte, Le Pont de l'Europe, 1876. Oil on canvas

• Structured around the bridge's iron framework, which dominates the right side of the canvas. The strong diagonal lines created by the bridge's structure and the sidewalk enhance the sense of depth and movement.

• A fashionably dressed man in the foreground, possibly a flâneur, strides confidently forward.

• A working-class figure, wearing simpler clothing, leans against the bridge's railing, looking towards the train tracks below.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Dance at the Moulin de la Galette, 1876. Oil on canvas

• The Moulin de la Galette was a lively dance hall and a popular gathering spot for Parisians, particularly the working class and artists, who would come to dance, socialize, and enjoy the festive atmosphere

• The scene is set outdoors, with people dancing in the foreground while others enjoy the festivities from the sidelines.

• He captures the natural sunlight filtering through the trees above, creating dappled patterns of light and shadow that play across the scene.

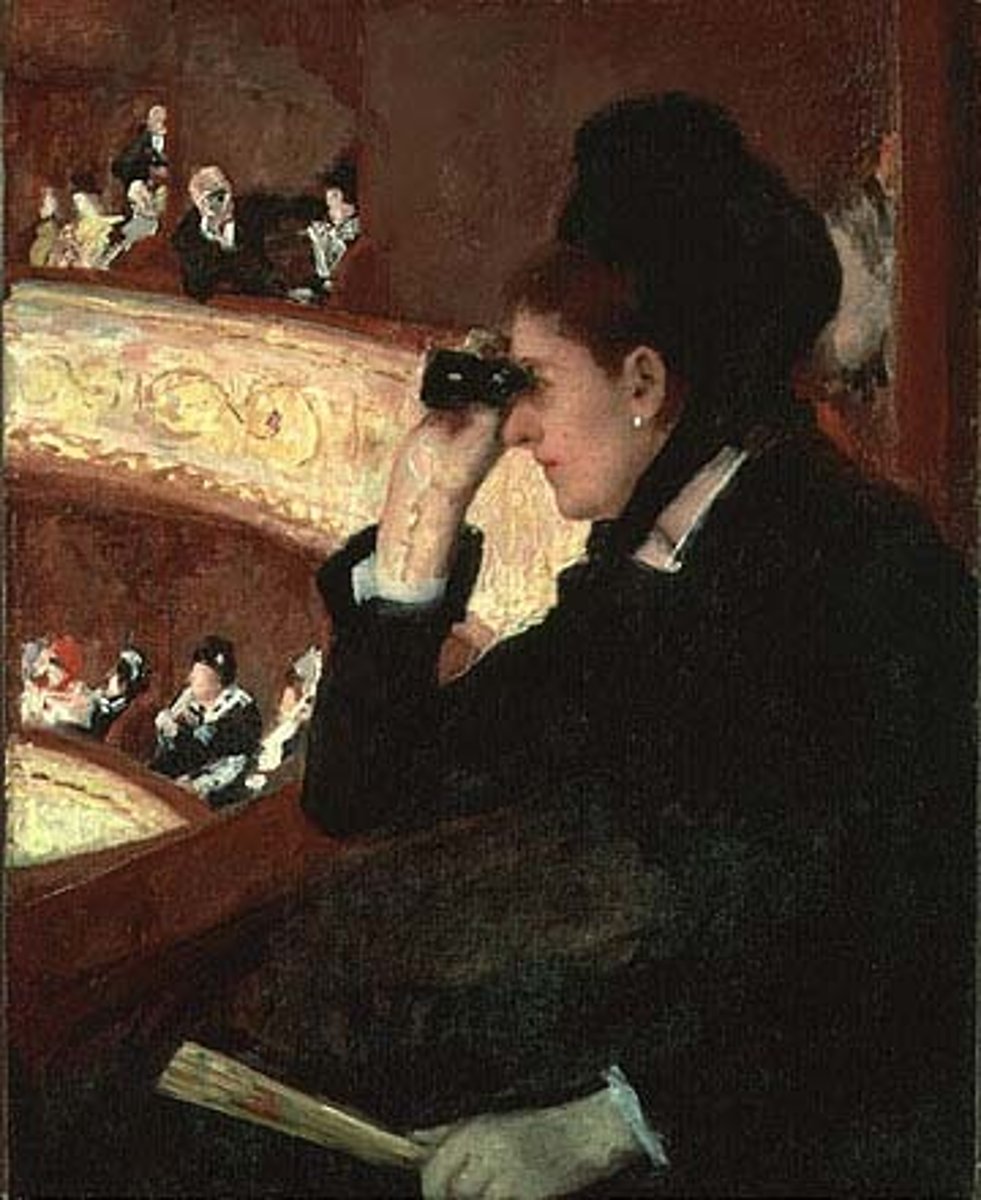

Mary Cassatt, In the Lodge, 1878

Oil on canvas

• Cassatt was particularly drawn to depicting women in social settings, often focusing on themes of motherhood, domestic life, and the experience of upper-class women in public spaces.

• Depicts a woman sitting in a theater box, known as a loge, intently looking through her opera glasses at the performance or audience below. The woman, elegantly dressed in black with a touch of white lace at her wrist, holds a fan in one hand while raising the glasses to her eyes. • The angle of the painting suggests that we, as viewers, are observing her from another box or from the audience below, reinforcing the idea of spectacle and observation.

• While the woman in the painting is actively engaged in looking, she is also being watched, highlighting the double-edged nature of women's visibility in public spaces.

Edgar Degas, Little Dancer Age 14, 1878-1881

pigmented beeswax, silk, linen, and cotton textiles

• Degas was deeply fascinated by the world of ballet, frequently depicting dancers in rehearsal, performance, or moments of rest.

• The sculpture captures the dancer in a poised yet slightly awkward stance. She stands en pointe, with her arms clasped behind her back and her chin slightly lifted. Her posture suggests discipline but also vulnerability—she is in a moment of training rather than performance.

• Her face, with its strong features and slightly upturned nose, does not conform to conventional ideals of beauty. Some contemporary critics found it unattractive, even "monkey-like," but Degas was not interested in flattery. Instead, he sought to capture the raw, unpolished essence of youth, ambition, and the physical toll of ballet training.

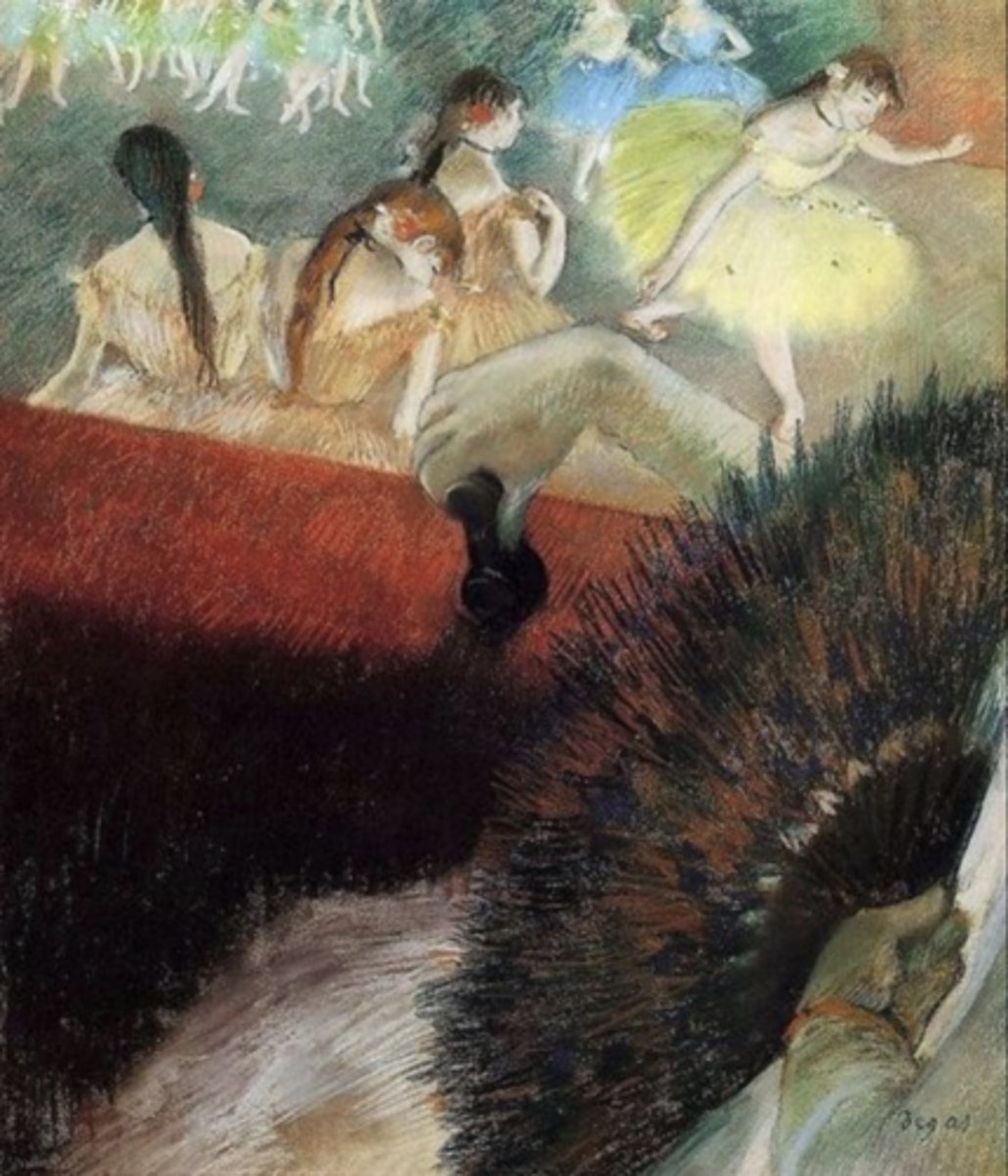

Edgar Degas, At the Theater, 1880

Pastel on Paper

• During the late 19th century, the theater was a prominent space for socializing among the Parisian bourgeoisie. It was not only a venue for performances but also a place where audiences observed each other as much as they watched the stage.

• He blends soft hues with bold contrasts to create the effect of dim theater lighting, using warm tones to suggest the glow of stage lights reflecting on the audience.

• The artwork highlights the dual role of theatergoers as both spectators and subjects of observation, a theme Degas explored in multiple works.

Berthe Morisot, The Psyche Mirror, 1876

Oil on canvas

• Morisot often painted domestic and feminine subjects, capturing moments of quiet reflection and everyday life with a loose, expressive brushstroke characteristic of the movement.

• Portrays a young woman gazing into a tall, full-length mirror (known as a "psyche" mirror). The subject appears unaware of the viewer's gaze, lost in her own world of self-reflection. This theme of introspection and quiet elegance was a hallmark of Morisot's work, offering a contrast to the more public scenes favored by other Impressionists.

• The woman's posture, with her slightly turned back and gentle stance, adds to the sense of intimacy, as if the viewer is catching a private moment rather than a posed portrait.

Berthe Morisot, Interior, 1872

Oil on canvas

• Presents a quiet, intimate domestic scene

• Morisot's loose, delicate brushstrokes create a sense of movement and softness, blending the figure with the surroundings in an almost dreamlike manner.

Berthe Morisot, Eugène Manet and his Daughter, 1881

Oil on canvas

• A portrayal of her husband, Eugène Manet and their daughter, Julie Manet.

• Morisot employs a loose yet deliberate composition, positioning Eugène Manet in a seated position while Julie stands beside him in what appears to be a garden or outdoor setting. The figures are naturally integrated into the landscape, with the background softly blending into the scene rather than being rigidly defined.

Berthe Morisot, Woman and Child in a Meadow, 1882

Oil on canvas

• This painting is characteristic of Morisot's preference for depicting intimate moments rather than grand narratives.

• Features a woman and child in an open meadow, surrounded by lush greenery. The positioning of the figures suggests a quiet, affectionate relationship, as they are close together in a peaceful moment. The meadow itself, with its wild grasses and flowers, feels untamed and natural, enhancing the sense of spontaneity in the scene.

• The figures seem almost to blend into their surroundings, emphasizing their connection to nature.

Berthe Morisot, Butterfly Hunt, 1874

Oil on canvas

• Presents a group of figures—likely children and possibly a mother—engaged in chasing butterflies.

• The composition is dynamic, with the figures slightly off-center, contributing to the sense of movement. The figures seem almost embedded within the lush landscape, emphasizing their connection to nature.

• Morisot's loose, expressive brushwork gives the painting an airy, spontaneous quality, making it feel as though it was painted quickly to capture a passing moment.

• The use of an open, outdoor setting contributes to the sense of freedom and energy.

Berthe Morisot, On the Balcony, 1872, Oil on canvas

• The painting captures a contemplative moment, with a young woman gazing out over the city from a balcony—a recurring motif in 19th-century art that symbolized both opportunity and separation.

• Balconies were a popular subject in 19th-century French art, often representing the tension between private and public life, especially for women.

• The painting features a young woman dressed in a dark outfit, standing with her back partially turned toward the viewer. She leans slightly on the balcony railing, gazing outward at the cityscape below. In the background, an urban setting is visible, though rendered in soft, loose brushstrokes typical of Impressionism. A child is also present, positioned lower in the composition, possibly reinforcing themes of family or generational contrast.

John Ruskin, Casa Loredan, 1846 Watercolor, ink, and graphite on paper

• Ruskin's travels to Venice fueled his passion for the city's buildings, and Casa Loredan was created as part of his extensive visual and written documentation of Venetian architecture.

• Highly detailed, emphasizing its pointed arches, delicate tracery, and ornate carvings

• Ruskin's watercolor technique enhances the depth and texture of the façade.

James Abbott McNeil Whistler, Nocturne in Blue and Silver, 1871-72

Oil on canvas

• Sought to capture the poetic and atmospheric effects of night scenes.

• Whistler's use of light in the painting is minimal, but it subtly glows against the backdrop of the deep blue sky, lending the piece a serene, ethereal quality.

• The smooth blending of colors and the minimal variation in tonal contrasts reflect his desire to evoke a specific mood—one of calmness and introspection, rather than a vivid or dynamic scene.

James Abbott McNeil Whistler, Nocturne in Black and Gold-The Falling Rocket, 1875

Oil on canvas

• The painting's color palette is primarily composed of deep blacks and muted golds, with the golden hues capturing the fleeting, ephemeral glow of fireworks.

• Whistler's focus on fireworks—a temporary and fleeting spectacle—speaks to the transient nature of beauty and experience.