Chapter 29: Oral Cavity and Salivary Glands

1/67

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

68 Terms

Dental Crowns

Short clinical crowns that are covered in cementum

Long (<10 cm) reserve crowns that lie embedded in the mandible or maxilla

How many roots do mature maxillary cheek teeth have?

Mature maxillary cheek teeth have three roots (a large, flat palatal root and a pointed rostral and caudal buccal root)

How many roots do mandibular cheek teeth have?

Mandibular cheek teeth usually only have a rostral and caudal root

How many pulp horns do the 07s to the 10s have?

The four central cheek teeth (07s to 10s) that are rectangular on cross section (mandibular) or larger and squarer on cross section (maxillary) each have five pulp horns

How many pulps do the 06s and mandibular 11s have?

The triangular shaped Triadan 06s and 11s each have six pulps

How many pulps do the maxillary 11s have?

Seven

Infundibulae

Maxillary cheek teeth each have two infundibulae that extend for almost the full tooth length in the young horse About 90% of infundibulae are incompletely filled with normal cement, and thus many infundibulae later develop caries that can lead to more significant disease Mandibular cheek teeth do not have infundibulae although deep infoldings of peripheral cement can give the appearance of such

Can overlong incisors keep the cheek teeth apart?

Because the cheek teeth have a surface area 10-15 times that of incisors and are composed of a harder type of enamel, it is mechanically impossible for overlong incisors to keep the cheek teeth apart

What percentage of infected mandibular and maxillary teeth have pulpar exposure?

Pulpar exposure is present in 34% of infected mandibular teeth and 23% of infected maxillary teeth

Muscles of the Tongue

Consists of a striated intrinsic lingual muscle proper and extrinsic muscles (genioglossus, hyoglossus, and styloglossus) that anchor the tongue to the mandible and hyoid apparatus

Tongue Anatomy

Subdivided into an apex (rostral free portion), a large body, and a relatively short root

A thin bar of cartilage may be present in the median plane just deep to the dorsal surface

A mucous membrane of variable thickness and with a dense submucosa covers the tongue musculature

Mechanical and sensory (taste) papillae invest the mucous membrane and the large vallate papillae (one to two pairs) are located at the approximate division of the tongue body and root

The dorsal surface of the root of the tongue is quite uneven because of the presence of lingual tonsillar tissue

Lingual Frenulum

The lingual frenulum is a ventral median fold of mucosa attaching the caudal aspect of the apex of the tongue to the oral cavity floor

Blood Supply to the Tongue

Blood supply to the tongue is via the lingual artery, which branches from the linguofacial trunk and enters the root of the tongue The lingual artery then continues as the deep lingual artery running rostrally and ventrally along the lateral aspect of the genioglossus muscle and supplying dorsal lingual branches

Motor Innervation to the Tongue

Hypoglossal nerve (XII) is the sole motor nerve to the tongue

Sensory Innervation to the Tongue

The lingual nerve (from the mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve (V)) and branches from the facial nerve (VII), glossopharyngeal nerve (IX), and vagus (X) provide regular and special sensory innervation

Salivary Glands Anatomy

Major salivary glands in the horse are the paired parotid, mandibular, and polystomatic sublingual glands

Also smaller buccal, labial, lingual, and palatine salivary glands

Distribution of serous and mucous cells within the salivary glands determines the nature of the saliva secreted

What type of fluid does the parotid salivary gland secrete?

Mainly serous fluid

What type of fluid do the mandibular and sublingual salivary glands produce?

A combination of serous and mucous fluids

Parotid Salivary Gland

Largest of the salivary glands

Located ventral to the ear in the retromandibular fossa between the vertical ramus of the mandible and the wing of the atlas

Rostral border reaches and may partially overlap the TMJ and the masseter muscle along the caudal border of the mandible

Caudal border extends to the wing of C1

Dorsally the gland extends to the base of the ear and ventrally it extends into the intermandibular space

Glandular secretions are drained by multiple small ducts that converge at the rostroventral aspect of the gland and exit as the single parotid (Stensen) duct Parotid duct initially passes along the medial surface of the caudal mandible in close association with the facial artery and vein The three structures then travel rostrolaterally around the ventral border of the mandible at the location of the palpable facial artery pulse The duct ascends along the rostral edge of the masseter muscle and opens into the buccal vestibule at the parotid papilla, which is located adjacent the maxillary third to fourth premolar tooth (07-08)

Mandibular Salivary Gland

Crescent-shaped and relatively smaller

Extends from the atlantal fossa to the basihyoid bone

Most of its lateral surface is covered by the parotid salivary gland and partly by the mandible

Its medial surface covers the larynx, common carotid artery, vagosympathetic trunk, and guttural pouch

Many small radicles unite to form a common duct that travels rostrally, ventral to the tongue The duct opens a few centimeters rostrolateral to the lingual frenulum, at the sublingual caruncle

Sublingual Salivary Gland

Small polystomatic sublingual gland lies beneath the oral mucosa between the body of the tongue and the mandible

Extends from the level of the mandibular symphysis to approximately the first or second mandibular molar (09-10)

Sublingual ducts (about 30) open independently at small papillae on the sublingual fold

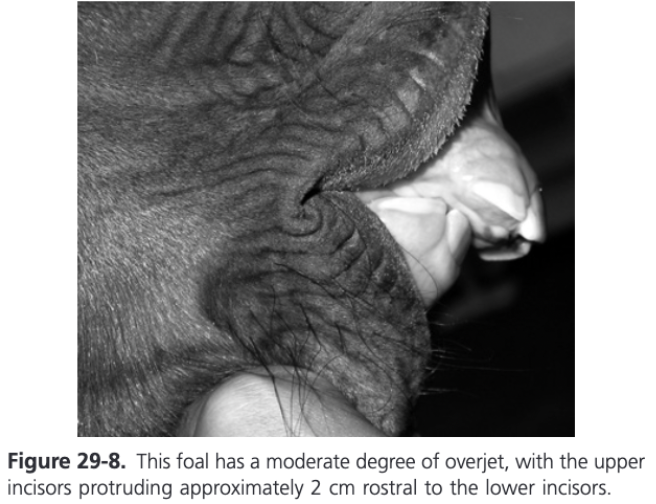

Overjet

Rostral projection of the upper incisors beyond the lower incisors in a horizontal plane

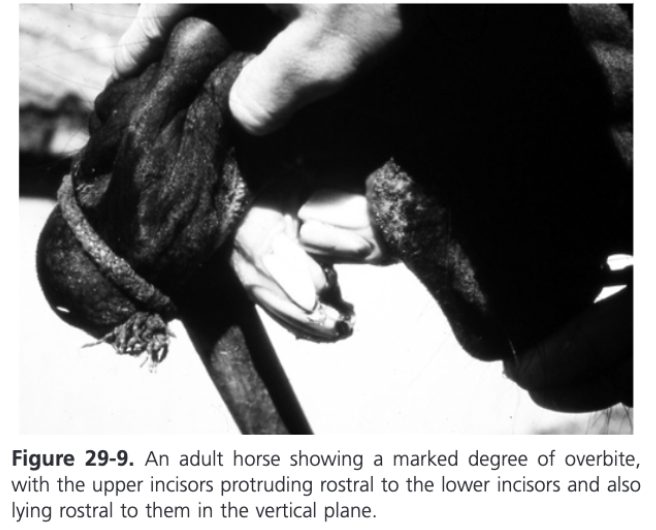

Overbite

Upper incisors as well as projecting rostrally to the lower incisors in the horizontal plane grow down in front of the lower incisors in a vertical direction

Overjet Treatment

In foals, overjet can be corrected or partially corrected by use of an incisor orthodontic brace, placing steel wires (a tension band) around the upper incisors and fixing these wires around the caudal aspect of the 507 and 607 to retard growth of the incisive bone and maxilla

Best performed at around 3 months of age but can be of value in foals up to 8 months old

1 cm horizontal incision made in the skin of the cheeks as dorsally as possible to avoid damaging the dorsal buccal branch, opposite the interdental spaces between the upper 07s and 08s

A short Steinmann pin fitted to a Jacobs chuck can be pushed through the skin wound to puncture the cheeks and enter the oral cavity

Point of the pin or drill is directed into the interdental (interproximal) space as close to the gingival margin as possible and is subsequently forcibly pushed (while twisting) through this tight space and directed dorsomedially to exit at the medial (palatal) interdental space, again close to the gingiva (at the border of the hard palate)

Steinmann pin is withdrawn and a 14 gauge needle is inserted along its path, followed by insertion of a 1.25 mm diameter stainless-steel wire of 60 cm in length through the needle into the interdental space and into the oral cavity

Most of the wire is drawn into the oral cavity and pulled rostrally to the incisors and the needle is withdrawn

External free end of the wire is directed through the buccal incision into the oral cavity directly adjacent to the initially passed part of the wire and then pulled rostrally following the buccal (lateral) aspect of the cheek teeth

Alternative technique is to use a 2.5 mm dental drill to create a hole at the gingival margin of the Triadan 07/08 interproximal space and insert the wire in a palatal-to-buccal direction and withdraw the free end along the buccal aspect of the cheek teeth toward the incisors

Two free ends of the wire are withdrawn from the mouth on either side of the cheek teeth, making them even in length and while pulling them rostrally the free ends are twisted together back to the rostral border of the upper 06s as dorsally as possible

The twisted wires are then placed over the labial (vestibular) aspect of the upper incisors (or interwoven between incisors at their gingival level) and their ends are trimmed

The wire knot should be embedded in PMMA to prevent soft tissue trauma

This technique is suitable for overjet but if overbite is present, the tension from this orthodontic brace may cause further caudo-ventral deviation of the upper incisors and incisive bone toward the rostral aspect of the lower incisors which would likely worsen the overbite

Treatment for Overbite

A biteplate can be fitted along with the orthodontic brace to promote indirect occlusion between the upper and lower incisors

Can be fashioned from a perforated (2-4 mm thick) aluminum plate that is cut to fit the shape of the rostral aspect of the maxillary incisors and hard palate, extending caudad about 4-5 cm (approximately 2 in) from the incisors

After fitting the wire brace, the underlying hard palate is covered in petroleum jelly and the biteplate covered with soft acrylic is placed on the hard palate

Additional acrylic should be placed beneath the caudal aspect of the bite plate so the sloped plate will tend to push the lower incisors more rostrally during prehension

Acrylic is used to joint the biteplate to the wires of the brace

Can also fit PMMA only without the aluminum plate

Bite plate may prevent the foal from suckling and cause discomfort to the mare's udder

Wires often break unilaterally of bilaterally and the orthodontic device was required to be replaced a median of twice in a study (Easley, Dixon, and Reardon, 2016)

Brace can be removed when the incisors are aligned or nearly so

Largest study to date showed complete reduction of overjet in 25% of cases and reduction of malocclusion to less than 5 mm in another 51% of cases (Easley, Dixon, and Reardon, 2016)

Fractures of the Incisors

Can occur because of trauma (usually kicks) and commonly result in exposure of the pulp (complicated dental fractures)

Young equine teeth (incisors and cheek teeth) have very wide apical foramina (root canal openings) along with a very large vascular pulp, which can resist the infection, and more so the inflammation that inevitably develops in orally exposed pulp

Regional nerve block, followed by the removal of any loose dental fragments and debridement of any exposed pulp with a 16 gauge needle is of benefit as first aid or as main treatment if endodontic treatment is not possible

Exposed aspect of the pulp canal should be filled with a calcium hydroxide preparation that promotes reparative tertiary dentine formation

Preferred treatment involves endodontic management through the damaged occlusal aspect

Usually consists of vital pulpotomy that involves removal of devitalized pulp, control of hemorrhage from the underlying vital pulp with paper points or hemostatic agents, followed by covering the healthy pulp with a calcium hydroxide or the application of mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) pulp dressing to stimulate tertiary dentine formation

After sealing the vital pulp, the remaining empty pulp canal is prepared for filling by etching it for 1 minute with a 40% phosphoric acid gel (to remove the smear layer and make the dental surface more porous to enhance mechanical bonding to dental restorative materials), which is then flushed away with water and air dried

The pulp canal is thinly coated with a bonding agent and filled incrementally in 2-3 mm layers with ultraviolet light curing of each layer suing a modern, composite restorative material

Equine Odontoclastic Tooth Resorption and Hypercementosis

When there is little resorption and much hypercementosis, the teeth are often stable and pain free and usually do not need treatment

If most teeth in an arcade are affected it is preferable to surgically extract all six incisors together

Continuous incision made in healthy gingiva 5 mm from the gingival margin of affected teeth on both the labial and lingual/palatal aspects

Gingiva is elevated in two large flaps above the alveoli of the affected teeth and the labial alveolar wall is removed but not as far as the apical region

Periodontal attachments of the teeth are broken down until they are loose and can be extracted

Protruding areas of alveolar bone are removed with bone rongeurs

Tension-free closure of gingival flaps

Disorders of the Canine Teeth (Triadan 04s)

Long-term unerupted canine teeth that cause mucosal ulceration and bitting problems in horses older than 7 years can be treated by performing deep cruciate incisions of the mucosa and underlying periosteum (operculation)

Surgical extraction is performed by initially creating a mucoperiosteal flap over the lateral alveolar wall

Lateral alveolar wall then removed

Remaining gingival margin is incised with a scalpel and the periodontal membranes are disrupted

Disorders of “Wolf Teeth” (Triadan 05s)

Most commonly develop in the maxilla rostral to the 06s

All mandibular wolf teeth should be extracted as they will contact a bit

Small wolf teeth in younger horses can be extracted using wolf tooth forceps or bone rongeurs alone

For other cases traditional instruments (Burgess or Musgrave elevators) can be used to separate the gingiva around the teeth but a sharp, long, offset dental elevator or luxator, or a #11 scalpel blade is more efficient and less traumatic

An elevator is inserted into different sites around the periodontal space to loosen the tooth and then it is extracted

Retained Deciduous Cheek Teeth

In the upper cheek teeth, premature extraction of caps leads to loss of most of the blood supply to the still-developing infundibular cementum, possibly leading to infundibular cemental hypoplasia (patent infundibulum) and thus predisposing the tooth to infundibular caries and possible apical infection or cheek teeth fracture later in life

Diastemata - Clinical Signs and Diagnosis

In some cases, cheek teeth diastemata are developmental in origin caused by lack of sufficient angulation of the rostral (06s) and caudal cheek teeth (10s and 11s) to provide enough compression of the occlusal surface of the six cheek teeth

In other developmental cases diastemata occur in horses with apparently normal cheek teeth angulation suggesting the dental buds have developed too far apart

Cheek teeth diastemata are the most common cause of painful dental disease in domesticated horses

Valve Diastemata

Diastemata that are narrow at the occlusal surface and wider at the gingival margin

Diastemata Treatment

Cleaning out the periodontal pockets and filling the periodontal defects with plastic impression material is of value in some cases but in many cases, this treatment only gives temporary relief unless the underlying mechanical predisposition to this food impaction is also treated

Developmental diastemata in younger horses should not be mechanically widened initially as these spaces may close when further dental eruption occurs

Feeding a finely chopped diet and not hay usually greatly reduces or abolishes the clinical signs of oral pain

Best treatment for severe diastemata in mature horses is to widen the diastemata to between 4 and 6 cm at the occlusal surface using a diastema burr

Water should be sprayed over the site being widened to prevent thermal pulpar damage and the site should be inspected every few second to ensure the site of widening is correct and the adjacent pulp horns are not exposed

Pulp horns are closer to the caudal aspect of the cheek teeth so as much tooth as possible should be removed from the rostral aspect of the tooth positioned caudal to the diastema

Idiopathic Fractures of the Cheek Teeth

Mainly affect the upper cheek teeth

Most commonly "slab" fractures occur through the two lateral pulp horns (pulp horns number 1 and 2)

In maxillary cheek teeth, the two exposed pulp horns often become effectively sealed off from the fracture site with reparative dentine and the remainder of the fractured tooth remains vital and continues to erupt normally

Apical infection and death of the fractured tooth occur more commonly with mandibular cheek teeth fractures

Midline (sagittal) fractures of the maxillary cheek teeth occur less commonly than slab fractures

Known to be secondary to advanced infundibular caries with coalescence of two carious infundibula leading to mechanical weakening followed by fracture of the tooth

The term infundibular caries-related cheek teeth fracture has been proposed

In the absence of apical infection, the retention of a large dental fragment is beneficial because it has some function in mastication, prevents drifting of adjacent cheek teeth into its space for a variable number of years and also decreases the development of major overgrowths (step mouth)

Restoration of Carious Indundibula

Performed to prevent further infundibular decay and potential fracture of affected cheek teeth by structurally strengthening them

May also prevent caries from extending into the pulp which can lead to apical infections

Impacted food debris and carious cementum are initially removed with a high-speed dental drill to a depth of circa 20 mm

Low-speed contra-angle dental drills with specialized long drill bits are then used to debride the infundibulum of impacted food material and abnormal cementum under endoscopic guidance

Hedstrom files of appropriate length are then attached to the slow-speed hand piece and used to complete the infundibular debridement

If a large occlusal opening is now present in the diseased infundibulum, high-pressure aerosol abrasion with fine silica or aluminum powder may be of value to debride diverticula that cannot be accessed by burrs or files

The cleaned infundibulum is flushed with sodium hypochlorite and acid etched, then a bonding agent is applied before it is filled in shallow layers with a modern composite restorative material with the use of ultraviolet light between layers

Dental (Odontogenic) Tumors

Rare

Can mimic apical infections (may cause maxillary and mandibular swelling that can become much larger than the swelling commonly associated with apical infections)

Swellings rarely develop sinus tracts and are usually firm and painless

Include ameloblastomas, which are noncalcified, epithelial tumors derived from the epithelium that forms enamel

Ameloblastic odontoma does induce calcification of adjacent mesenchymal tissues (and reciprocally of enamel epithelium) and so also contains dentine, cementum, and enamel

Appearance of these tumors can vary from a noncalcified, polycystic, fibrous type of tumor to growth containing such tissues along with calcified dental tissues

Also include a variety of calcified tumors from dentinal tissues (odontoma) or cement (cementoma) or more commonly combinations of all three dental components (compound odontoma or ameloblastic odontoma)

Cheek Teeth Periapical Infection

If an apical infection (with death of pulp) has been present for many months, the secondary dentine worn away on the occlusal surface by normal mastication is not replaced and therefore with further eruption and occlusal wear occlusal puplar exposur occurs over all pulp horns

Anachoresis

Blood or lymphatic borne infection of pulp

Infraorbital Nerve Block

Insert 5 cm, 21 gauge needle 3-4 cm caudad into the infraorbital canal and then slowly inject 3-5 mL of lidocaine to anesthetize the upper 06s or 07s

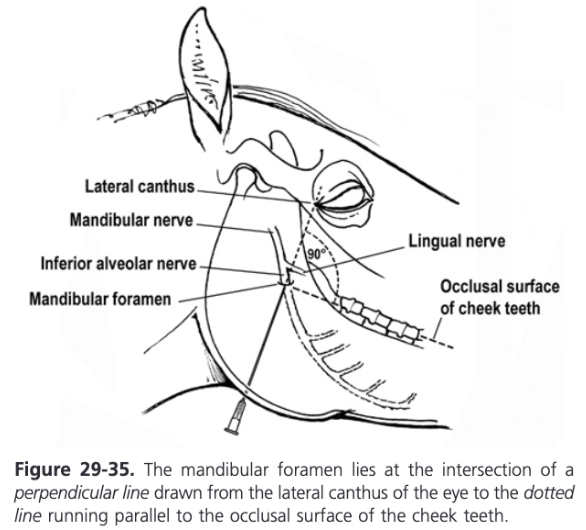

Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block

Sensory to all mandibular teeth

Anesthetized as it enters the mandibular canal via the mandibular foramen on the medial aspect of the ramus of the mandible

Mandibular foramen lies at the intersection of a perpendicular line drawn from the lateral canthus of the eye to the line running parallel to the occlusal surface of the cheek teeth

A 15 cm, 18 gauge spinal needle is walked up the periosteum of the medial aspect of the mandible and 20-30 mL of lidocaine is deposited at the site and 1-2 cm dorsocaudally to it

Maxillary Nerve Block

Inject local anesthetic into the extraperiorbital fat and allow it to diffuse to the maxillary branch of the trigeminal nerve

5 cm needle inserted immediately ventral to the zygomatic process between the middle third and caudal third of the orbit

Needle is directed in a rostro-medio-ventral direction and inserted 30-35 mm through the masseter muscle

A decrease in resistance if detected as it enters the extraperiobital fat body

Needle is advanced 15-20 mm further and 20 mL of local anesthetic inserted

May take 20 minutes or more for the maxilary nerve to become anesthetized

Postoperative Complications Following Oral Extraction of Cheek Teeth

After successful oral extraction postoperative complications are rare (10% of cases) and are usually minor in nature (nonhealing alveoli caused by alveolar sequestrum or localized osteitis)

Repulsion of Cheek Teeth

Complications commonly occur after repulsion of apically infected cheek teeth in younger horses because much mechanical damage occurs to the alveolar and supporting mandibular or maxillary bones by the high and often prolonged forces required

Problems include nonhealing alveoli as the result of residual dental fragments or alveolar/supporting bone sequestra, localized osteomyelitis, oronasal, orofacial, and oromaxillary fisutlae, chronically draining facial tracts, damage to adjacent teeth, and chronic sinusitis

Between 32 and 70% of cases of equine dental repulsion require additional surgical and nonsurgical treatments with most complications occurring following maxillary cheek teeth repulsions

Removal of the Lateral Alveolar Plate (Lateral Buccotomy Technique)

5-7 cm horizontal incision (to reduce the risk of cutting the buccal branches of the facial nerve) is made in the skin and soft tissues overlying the affected cheek tooth

Vertical incision made in the periosteum over the lateral aspect of the affected cheek tooth and the periosteum is reflected

Using an oscillating bone saw or a high-speed burr, the lateral alveolar wall is removed

Full length of the crown of the exposed diseased tooth is sectioned longitudinally with a diamond wheel or large solid carbide burr before the cheek tooth is extracted in sections

Potential major disadvantages is that it can cause marked intraoperative hemorrhage, parotid duct puncture, and nerve damage with consequent rostral facial paralysis

Endodontic Therapy

Used to be performed retrograde (through the apex of the affected cheek teeth)

Now usually performed orthograde (via an intraoral approach through the occlusal surface of the affected tooth)

Cannot be used in teeth with gross sepsis of the apex or where there is extensive periodontal disease

Retrograde Endodontic Therapy

Performed via surgical approaches through the mandibular or maxillary bones

Consequence of this approach is the need for prolonged general anesthesia and surgical exposure of the overlying bone and affected apex for endodontic therapy

Exposed apex is visually assessed and grossly infected or discolored calcified dental tissue is removed by high-speed, water-cooled burrs

All pulps and any impacted vegetable material is removed

Canals are filed using long Hedstrom endodontic files until normal-appearing dentine is reached

Pulp canal is sterilized by irrigating it with 2-5% sodium hypochlorite solution followed by lavage with water and air-drying

Canal walls are etched with a phosphoric acid preparation and lavaged and dried again

Surface is coated with a dental bonding agent (some need to be cured by UV light) and subsequently the pulp canal is filled incrementally in 5 mm layers as completely as possible with a modern composite restorative material, some of which also needs to be cured by UV light

An 84% success rate with (apical) endodontic therapy for mandibular 08s and 09s has been reported but only poor success with maxillary cheek teeth

Most comprehensive report to date has shown complete success in only 58% of cases and partial success in 17% (simhofer, Stoian, Zetner, 2008)

Orthograde Endodontics

More successfully used with reported 80% success rate

Advantages of being less invasive and not requiring general anesthesia

Specialized training and equipment is required

The occlusal surface of the affected tooth is reduced with a mechanical float to decrease the thickness of secondary dentine overlying the pulp horns

Secondary dentine covering each individual pulp horn is then drilled with a low-speed drill to allow visual evaluation of the pulp horns

Any pulps that are found to be healthy have a calcium hydroxide paste or MTA dressing applied and are then sealed using described endodontic techniques

Pulps that are inflamed or necrotic are removed with broaches and damaged dentine lining the pulp canals is removed with Hedstrom files combined with high volume lavage with saline or 0.1% chlorhexidine

If the apical areas cannot be fully accessed, pulp canal lavage with 0.5% sodium hypochlorite (Dakin solution) can be used to dislodge and help remove necrotic tissue

Following saline lavage and drying the apical aspect of debrided pulp horns are then filled with calcium hydroxide paste

Standard endodontic filling is placed in the occlusal 15 to 20 mm of the treated pulp canals

Trauma of the Tongue

Transverse lacerations are more frequent than longitudinal ones

Free portion of the tongue is usually involved

Partial glossectomy, primary wound closure, or secondary wound healing are approaches to treatment

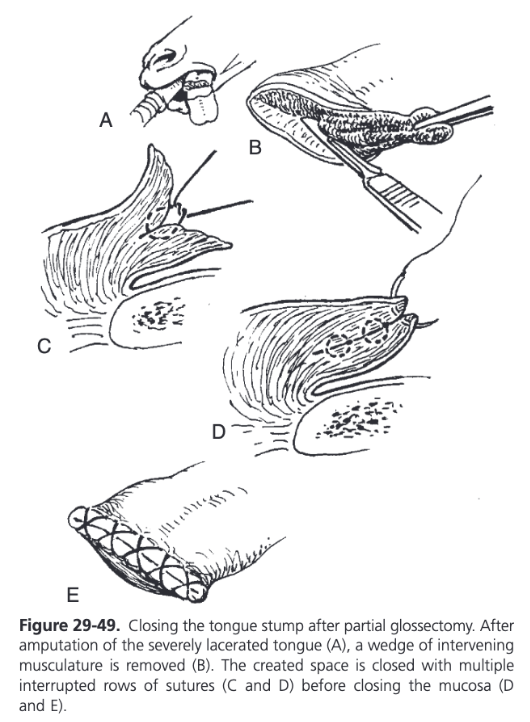

Partial Glossectomy

Reserved for cases in which the rostral tongue tissue is devitalized and minimal attachment is left between the severed section and the remaining body

Tissue color, temperature, and evidence of bleeding at an incision can be used to assess viability

Observation of fluorescence after intravenous administration of sodium fluorescein allows a more objective assessment of tissue vascularization

Mucosal to mucosal closure of the stump is not imperative but is encourages to aid hemostasis, reduce postoperative discomfort associated with an exposed tongue stump, and to hasten wound healing

Correct dorsal-ventral apposition is assisted by removing a wedge of intervening musculature and closing the created space with multiple rows of interrupted absorbable 2-0 or 0 sutures

If necessary, full-thickness tension-relieving mattress sutures may be placed caudal to the mucosa edges to provide additional support to the wound margins

Mucosal edges are closed with exposed or buried 2-0 or 0 absorbable sutures

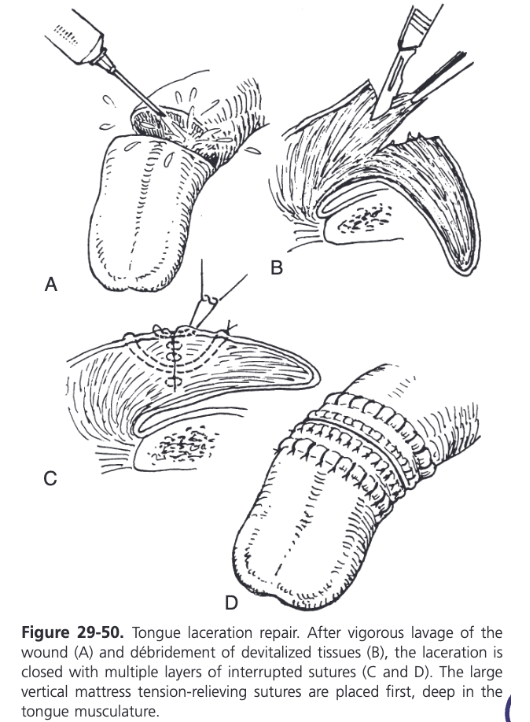

Primary Closure of Tongue Lacerations

Encouraged when possible

Wound edges debrided and lavaged

Multilayer closure to eliminate dead space is recommended

To relieve tension on the closure, vertical mattress sutures are preplaced deep in the muscular body of the tongue with absorbable or nonabsorbable size 0 or 1 monofilament suture material

Buried rows of simple interrupted 2-0 to 0 monofilament absorbable sutures are subsequently used to appose the muscles, obliterating dead space

Vertical mattress sutures are tied and the lingual mucosa is apposed with simple continuous or interrupted vertical mattress sutures

Second Intention Wound Healing of Tongue Lacerations

Lacerations that have healed by second intention but result in poor tongue functionality can be reconstructed using primary closure techniques after sharp debridement of scar tissue

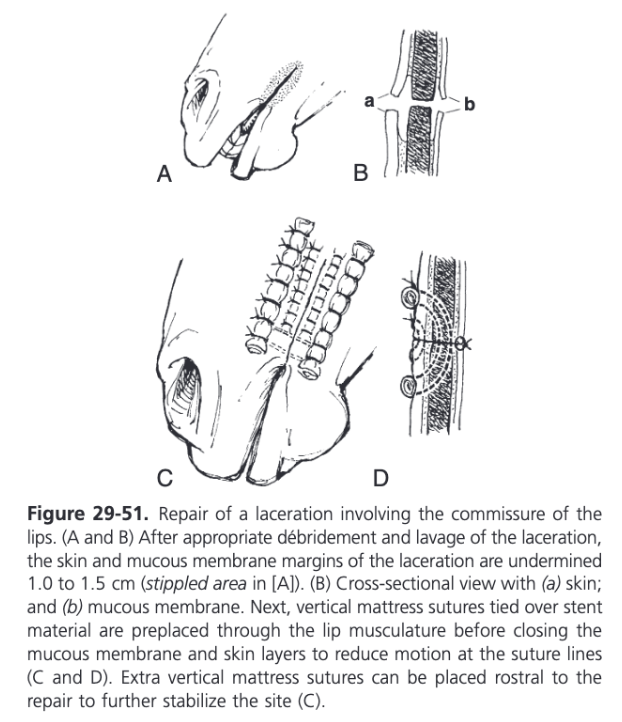

Trauma of the Lips

The lips are highly mobile tissues and close adherence of the mucosa and skin to underlying musculature results in excessive motion at sutures lines during prehension leading to a high incidence of dehiscence

To reduce motion on the suture lines, margins of the skin and oral mucosa are sharply undermined for 1-1.5 cm from the edges of the wound

Vertical mattress 0-1 nonabsorbable sutures are subsequently preplaced from the extraoral side through the lip musculature and tied over quills of soft rubber tubing

Mucous membrane is closed with simple continuous or interrupted 2-0 monofilament absorbable suture

Skin is apposed with simple interrupted or vertical mattress 2-0 to 0 nonabsorbable monofilament sutures

At the mucocutaneous junction, a vertical mattress pattern is recommended for precise apposition

When repairing laceration involving the commissure of the lips, additional vertical mattress tension-relieving sutures are placed rostral to the primary repair for increased support in this highly mobile area

Most common postoperative complication is dehiscence of the repair

Extensive Lower Lip Lacerations

For extensive lower lip laceration with loss of tissue, a rotational flap may be used

Avulsions of the lower lip should be supported to minimize dead space and motion at the repair site with large mattress sutures passed through the mandible at the appropriate location to maintain anatomical alignment

Wire or nonabsorbable suture material is threaded from the external surface of the lip and chin through drilled holes in the mandible and then returned to the external surface for tying

Stents of soft tubing or buttons are typically placed under the sutures on the oral and external sides

Persistent Lingual Frenulum

Ventral ankyloglossia (persistent lingual frenulum) is a very rare congenital condition in foals and may accompany other congenital craniofacial anomalies

Tongue cannot be protruded normally because of a mucosal attachment between the ventral rostral free part of the tongue and the floor of the oral cavity

Difficulty nursing can also occur

Frenuloplasty is the treatment of choice

Membrane is sharply transected with scissors, can also use electrocautery and laser division of the tissue

Oral Cavity Soft Tissue Neoplasia

Most common primary oral neoplasm is squamous cell carcinoma affecting any of the mucosal surfaces

Other primary or metastatic tumors include melanoma, fibrosarcoma, hemangiosarcoma, lymphosarcoma, rhabdomyoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, nerve sheath tumors, adenocarcinoma, focal tumors of the tongue of unknown origin, and mast cell tumor

Often mandibular lymphadenopathy in horses with oral neoplasia is caused by reactive inflammation rather than metastatic disease so biopsy results of these lymph nodes are often negative

Invasive squamous cell carcinomas have a high recurrence rate after surgical excision, radiotherapy after radical surgical excision may prevent or prolong time to recurrence

Fibrosarcomas also tend to recur after excision and are less responsive to radiation therapy

Prognosis for resolution of oral squamous cell carcinoma and fibrosarcoma is generally poor

Nonneoplastic conditions that should be differentiated from tumors include focal gingival hyperplasia and exuberant granulation tissue

Epulis

Tumor-like masses on the gingiva

Trauma of the Salivary Glands

Superficially located parotid salivary gland and duct are subject to trauma more than the better protected mandibular and sublingual glands

If there is no indication that a salivary duct or gland has been damaged, it is recommended that parotid wounds be left to heal by second intention

Most salivary fistulas spontaneously close within 1-3 weeks so delaying treatment for a period of weeks is a worthwhile option

If the severed duct ends can be drawn into proximity with each other, primary closure of an acutely lacerated duct or a nonhealing salivary fistula is facilitated by suturing the duct over an intraluminal tube or by placing three sutures to appose the two cut ends as a triangle and suturing between the apices

Size 2 nylon suture can be threaded normograde through the rostral segment of the lacerated duct to the parotid papilla

Tubing is passed via a 14 to 16 gauge needle cannula inserted through the cheek tissue externally to internally enter the oral cavity just rostral to the parotid papilla

Tubing is guided over the nylon suture into the duct and the nylon and needle are removed

When the tip of the tube emerges from the rostral segment of the lacerated duct at the wound, it is redirected into the caudal segment of the duct and passed to the ventral aspect of the parotid gland

Duct is closed with fine absorbable or nonabsorbable suture (4-0 to 7-0) using a simple interrupted pattern

The external end of the tube is sutured to the side of the face, allowing ease of later removal and the ability to check for continued patency of the duct

For tears involving one side of the duct wall, suture repair without use of an in situ stent should be adequate

If anastomosis of the duct is not possible because of loss of too much intervening tissue, an interposition polytetrafluoroethylene tube graft may be successful in restoring duct continuity

For smaller gaps left between duct ends that cannot be directly anastomosed, a temporary stent may be successful in restoring duct function

Ligation of the Salivary Duct

For ligation, the parotid duct is readily located close to its origin from the gland where it crosses the tendon of insertion of the sternomandibularis muscle

A catheter is passed retrograde through the duct from the salivary fistula site toward the gland

2 or 3 heavy-gauge nonabsorbable suture should be used for duct ligation and should not be tied too tightly to prevent cutting through the duct wall

Distal suture is tied first to distribute resulting back pressure after ligation

Chemical Involution of the Salivary Gland

Chemical involution of the parotid gland is achieved by using 10% formalin which ahs been found to produce the least amount of necrosis and suppurative inflammation of the gland compared with other agents

Water soluble iodinated contrast material is also effective in eliminating glandular secretions

Duct is cannulated and a ligature tied to prevent leakage

35 mL of formalin are injected through the cannula into the gland

It is left in for 90 seconds and then allowed to drain out

The cannula is left in place for 36 hours

Cessation of salivary secretions occurs by 3 weeks

Postoperative complications include periocular and facial swelling, transient facial nerve paralysis, anorexia, and dyspnea - most associated with the use of chlorhexidine and silver nitrate and not with formalin

Sialoliths

Composed primarily of calcium carbonate and organic matter

Plant material often found as a nidus

Parotid duct most commonly involved with a few cases affecting the mandibular duct

Obstruction of the duct is often incomplete and saliva may continue to pass around the sialolith

With acute or chronic complete obstruction, back pressure may cause duct and gland distension which is noticed as a possibly painful swelling in the intermandibular and retromandibular space

Usually occur singularly

Smaller parotid duct calculi may be massaged through the oral opening of the duct at the parotid papilla

If the calculus is palpable orally in the buccal soft tissues, direct intraoral incision over the sialolith leaving the wound to heal by second intention is preferred

Uncomplicated mandibular duct calculi may be removed by incising over the palpable sialolith intraorally, usually near the sublingual caruncle

Intraoral approach prevents external salivary fistula development

Calculi inaccessible by the intraoral route are removed by transcutaneous longitudinal incision of the duct or in the case of draining tracts, exploration of the tract can lead to the calculus

Closure of the duct is performed with a simple interrupted or continuous pattern of fine absorbable suture material

Surgical wounds associated with sialolith removal in septic sialoadenitis cases are managed by open wound healing

Antimicrobials and lavage of the duct and gland via catheterization of the oral opening are recommended in infected cases

A recent report indicated that sialoliths located in the caudal aspect of the parotid duct, closer to the gland and with cutaneous draining tracts were associated with more short term healing complications (Carlson, Eatman, and Winfield, 2015)

Long term prognosis is very good but a 24% recurrence rate was determined

Septic Sialoadenitis

Septic sialoadenitis is a rare occurrence in equids but may precede or be a consequence of a developing sialolith

Inflammation and infection of the duct results in obstruction by exudates, desquamated cells and mucus which may provide the nidus necessary for a sialolith to form

Partial obstruction of the duct by a sialolith may decrease natural clearance of secretions, resulting in stasis and facilitating proximal movement of bacteria

Fever, painful swelling of the affected gland, and cutaneous draining tracts are common clinical findings

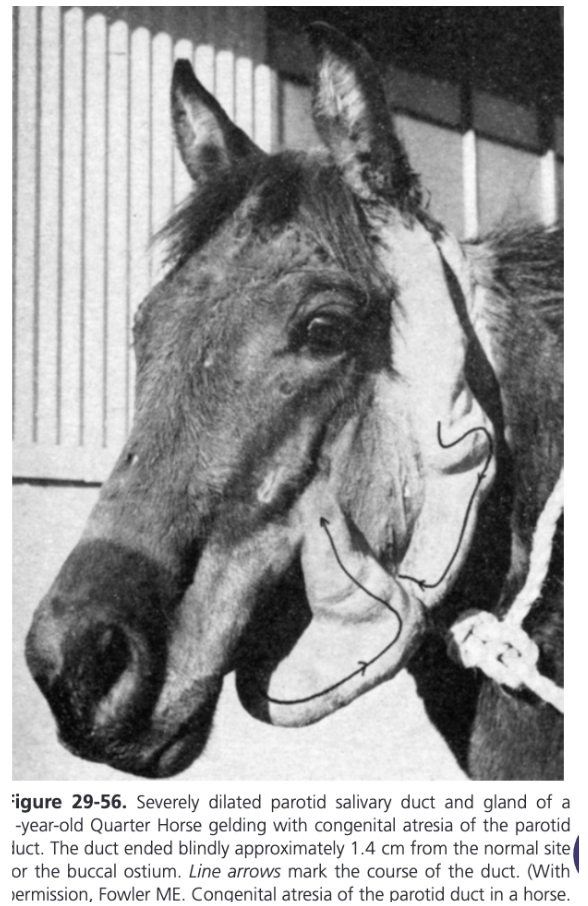

Atresia of the Parotid Salivary Duct

Rare

Proximal to the obstruction, the dilated duct is characterized by a nonpainful, tortuous, subcutaneous, fluid-filled tube that extends caudad from a point rostral to the masseter along the ventral surface of the mandible to the base of the ear on the affected side

Treatment options include surgically creating a new buccal ostium, duct excision and proximal ligation, gland extirpation, and chemical ablation of the salivary gland

Creation of a buccal fistula is not recommended because of its probably spontaneous closure and potential for ascending contamination of the duct

In one case, removing a large portion of the distended duct and ligating individual radicles was successful

Duct ligation may not be appropriate in a chronic case as severe dilation may not allow enough back pressure to be generated to cause atrophy of the gland and cessation of secretory activity

Chemical ablation is recommended in most cases

Salivary Mucocele or Sialocele

Pocket of saliva in a space not lined by epithelium

Ranula (Honey Cyst)

A mucocele of the mandibular duct or sublingual salivary gland ducts and is seen as a bluish-tinged cyst on the floor of the mouth

Salivary Mucocele and Ranula

Aspirated fluid is generally brown and mucinous with a higher concentration of calcium and potassium than in other accumulations of fluid and it also contains amylase

Contrast sialography can determine if there is any communication between the cavity and the duct or gland

In some cases complete surgical removal of the structure is appropriate

Ranulas respond well to marsupialization into the oral cavity

A catheter can be sutured in place for 2-3 weeks to create a permanent fistula

Marsupialization of a mucocele into the buccal cavity is less likely to be successful because of lack of epithelial lining

Chemical ablation would be effective and may be the simplest approach if the gland is known to communicate with the mucocele directly or via the duct

Heterotopic Salivary Tissue

Definitive diagnosis is by histopathology and complete surgical removal resolves the condition

Chemical ablation may also be performed if the nature of the tissue can be ascertained beforehand

Idiopathic Parotiditis (Grass Glands)

Syndrome of recurrent salivary gland swelling that occurs acutely in association with pasture turnout

Parotid salivary glands become swollen during the day while the horse is on pasture and the swelling resolves overnight when the horse is stalled

Well recognized in Europe and Australia but rare in the US

Salivary Gland Neoplasia

Adenocarcinoma, acinic cell carcinoma, lymphoma, melanoma, mixed cell tumor, and peripheral nerve sheath tumor have been reported in equine salivary glands

Treatment is often palliative because wide surgical margins frequently fail to prevent benign mixed cell tumors or acinar tumors and advanced melanomas from recurring

Adenocarcinomas often metastasize

Lymphomas can respond to radiation therapy

A well-encapsulated peripheral nerve sheath tumor was surgically excised with no recurrence at 6 months