Pharm107 - Intro to Titration

1/54

Earn XP

Description and Tags

Covering the topics of Chemical Basis of Titrimetry up to Titration Curves

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

55 Terms

Titrimetry

A group of chemical methods of quantitative analysis in which the concentration of an analyte is determined based on its stoichiometric reaction with a reagent of established concentration introduced to a sample gradually, in small portions until the analyte is consumed quantitatively

“Chemical Methods of Quantitative Analysis”

Involves chemical reactions between the analyte and a reagent.

Requires that substances are chemically reactive in the given chemical environment.

Stoichiometry in Titration

Ensures reacting species combine in fixed ratios based on their balanced chemical equation.

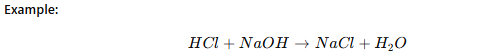

Example:

If 10 equivalents of NaOH are required to neutralize HCl, then the solution must contain 10 equivalents of HCl.

Equivalents: The amount of a substance that reacts in a 1:1 ratio with another.

Interfering Species in Titration

Titration accuracy depends on minimal interference from other substances.

Example:

Both Mg²⁺ and Al³⁺ react with EDTA in a 1:1 ratio.

To analyze Mg²⁺ without interference, the solution is buffered at pH 10, where Al³⁺ is masked by Triethanolamine (TEA).

This ensures only Mg²⁺ reacts with EDTA.

Standard Solution (Standard Titrant)

A reagent of known concentration used in titrations.

Also called Volumetric Solution (VS).

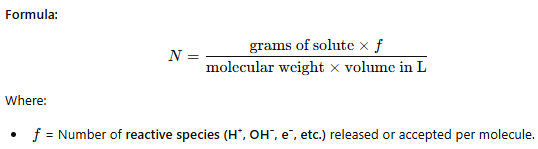

Normality (N) of a Solution

Expresses the number of equivalents of solute per liter (1000 mL) of solution.

Equivalence Point

Theoretical point where titrant amount is chemically equal to the analyte.

Endpoint

Observable indication (e.g., color change) that the reaction is complete.

Appropriate Indicator

Selected with the goal of minimizing the gap between the equivalence point and the endpoint.

Indicators in Acid-Base Titration

Are weak acids/bases that change color near the equivalence point.

Examples:

Phenolphthalein: Colorless (acid) → Pink (base) at pH 8.2-10.

Methyl Orange: Red (acid) → Yellow (base) at pH 3.1-4.4.

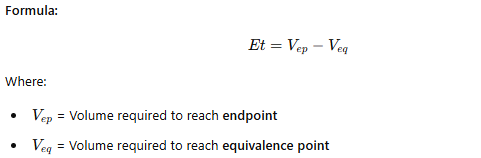

Titration Error (Et)

The difference between the actual endpoint and theoretical equivalence point.

Volumetric Titration

A method wherein the volume of a standard reagent is measured and is used to quantify the unknown concentration of the analyte.

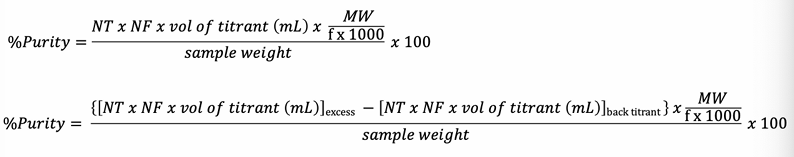

Percentage of Purity

The proportion of a pure substance within an impure sample, expressed as a percentage

Gradual Addition in Titration

Titrant must be added slowly to prevent overshooting the endpoint.

As the equivalence point approaches, titrant is added in increasingly smaller portions.

At the endpoint, even half a drop of titrant can cause a color change.

Titrant Methodology

Step 1: Titrant is added to the analyte while swirling.

Step 2: Initially, titrant is added rapidly.

Step 3: As the endpoint approaches, titrant is added in smaller portions.

Step 4: At the endpoint, even a fraction of a drop can cause a color change.

Types of Titration (Based on Methodology)

Direct Titration

Residual Titration (Back Titration)

Titration with Preliminary Treatment

Direct Titration

The most common titration method.

Requires that the reaction occurs rapidly.

If titration is added too fast:

The endpoint may overshoot the equivalence point, leading to errors.

Back Titration (Residual Titration)

Used when direct titration is impractical (e.g., slow reactions, insoluble analytes).

Steps:

Add excess titrant to react with the analyte.

Introduce a second titrant to measure the unreacted portion.

Subtract the excess titrant from the total added to determine the exact analyte concentration.

Back Titrant

The second titrant or the standard solution used to quantify the excess titrant.

Formaldehyde Analysis

An example of Back Titration wherein the reaction is slow, making direct titration difficult.

Excess iodine solution (I₂ VS) is added.

Wait 15 minutes to allow the reaction to complete.

Remaining unreacted iodine is titrated to determine the formaldehyde content.

Titration with Preliminary Treatment

Also called Indirect Titration

Used when the analyte cannot be directly titrated.

The analyte undergoes a chemical reaction or separation to form a titratable species.

Kjeldahl Titration for Urea Analysis

An example of Indirect Titration

Digestion: Urea is converted into ammonia (NH₃).

Distillation: NH₃ is separated and titrated directly.

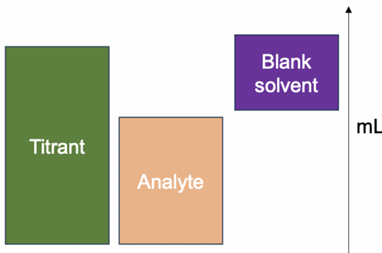

Blank Correction

The endpoint in titration is an estimate of the true equivalence point.

Why use blank correction?

Accounts for impurities or side reactions.

Increases the accuracy of results.

Blank Correction Methodology

Perform titration with the analyte and record the volume of titrant used.

Perform a second titration without the analyte (blank titration).

Subtract the blank titration volume from the original titration volume.

Types of Titration (Based on Chemical Reactions)

Neutralization Titration

Redox Titration

Complexometric Titration

Precipitation Titration

Neutralization Titration

Used in acid-base titrations.

The endpoint is detected using:

pH indicators (e.g., phenolphthalein, methyl orange).

pH meters for precise measurement.

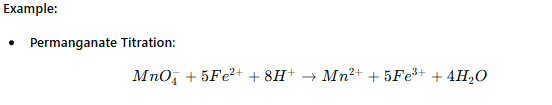

Redox Titration

Involves oxidation-reduction reactions.

One species loses electrons (oxidation), while the other gains electrons (reduction).

Complexometric Titration

Used for metal ion determination.

A metal ion reacts with a chelating agent (e.g., EDTA).

Example:

Determination of Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ using EDTA.

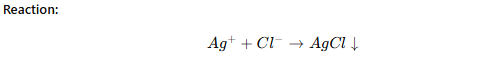

Precipitation Titration

The analyte forms an insoluble precipitate with the titrant.

Example:

Determination of chloride ions (Cl⁻) using silver nitrate (AgNO₃).

Types of Titration (Based on Detection Methods)

Visual Methods

Potentiometric Methods

Amperometric Methods

Coulometric Methods

Thermometric Methods

Automated Titrations Visual Detection Method

Visual Detection Method

Uses an indicator to signal the endpoint through a color change.

Common in acid-base titrations.

The indicator must have a clear and sharp color transition.

Examples:

Phenolphthalein: Colorless → Pink at pH 8.2-10.

Methyl Orange: Red → Yellow at pH 3.1-4.4.

Mixed Indicators

A combination of two or more indicators.

Used when a single indicator does not provide a sharp color change.

Example:

Titration of NaOH + Na₂CO₃ mixture using HCl.

Uses phenolphthalein (first endpoint) and methyl orange (second endpoint).

Potentiometric Detection Method

Measures voltage (electrical potential) changes during titration.

No indicator needed, ideal for colored or turbid solutions.

Uses indicator and reference electrodes (e.g., pH meter).

Equivalence point found at sharpest voltage change.

Amperometric Detection Method

Measures microcurrent changes as titrant is added.

Used in precipitation titrations (e.g., AgNO₃ titrations).

Requires two electrodes to monitor current flow.

Precise for low-concentration analytes.

Coulometric Detection Method

Determines analyte concentration by measuring electrical charge.

Based on Faraday’s Law of Electrolysis.

Used in Karl Fischer titration for trace water analysis.

Highly accurate for very small analyte amounts.

Thermometric Detection Method

Tracks temperature changes caused by the reaction.

Works well in acid-base titrations and exothermic reactions.

No indicator needed, useful for cloudy or colored solutions.

Endpoint found at the sharpest temperature change.

Automated Titration Method

Uses a computerized system for precise titration.

Motorized burette adds titrant at a controlled rate.

Sensors (e.g., pH meters) detect endpoint automatically.

Minimizes human error and improves reproducibility.

Standardization

Process of determining the exact concentration of a volumetric solution.

Ensures titration results are accurate and reproducible.

Uses a primary standard, secondary standard, or another standard solution.

Essential for reliable titrimetric analysis.

Volumetric Standards

Standard solutions used in titration.

Must be stable, react completely, and have a known concentration.

Used to quantify an analyte’s concentration with precision.

Commonly expressed in normality (N) or molarity (M).

Ideal Characteristics of a Volumetric Standard

Stable: Does not degrade over time.

Fast-reacting: Ensures quick, complete titration.

High purity: Minimizes errors in concentration calculations.

Well-defined reaction: Follows a balanced chemical equation.

Preparation of Volumetric Solutions (VS)

Prepared using official procedures from the pharmacopeia.

Measured with volumetric glassware for precision.

Prepared at standard temperature (25°C).

Concentration must be verified through standardization.

Empirical Concentration

The actual concentration of a solution, determined experimentally.

May differ from the theoretical concentration due to impurities.

Requires standardization to obtain accurate values.

Standardization of Volumetric Solutions

A volumetric solution's concentration is determined by titration against:

A primary standard.

A secondary standard.

A standard solution of known concentration.

Ensures the solution’s concentration is accurate and reliable.

Primary Standard

A highly pure, stable compound used for standardization.

Must have a well-defined composition and high molar mass.

Used to determine the exact concentration of secondary standards.

Example: Sodium carbonate (Na₂CO₃) for acid titration.

Characteristics of a Primary Standard

High purity: Minimal contamination.

Atmospheric stability: Does not react with air or absorb moisture.

Absence of hydrate water: Water content remains constant.

Modest cost

Reasonable solubility: Must be soluble in titration medium.

Reasonably large molar mass: Reduces weighing errors.

Secondary Standard

A compound whose concentration is determined by standardization.

Used as a working standard in titration.

Less pure and requires validation against a primary standard.

Example: Sodium hydroxide (NaOH), which absorbs moisture and CO₂.

Titer Value

The mass of a substance (in grams) that reacts with 1 mL of a standard solution.

Used to determine the exact analyte concentration.

Example: Hydrochloric acid titer value in acid-base titrations.

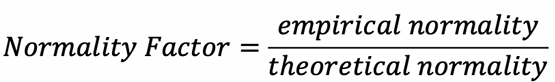

Normality Factor (Correction Factor)

A correction value used to adjust standard solution concentration.

Accounts for deviations from the expected normality.

Ensures greater accuracy in titration calculations.

Titration Curve

A graphical representation of a titration process.

Plots p-function of the analyte (e.g., pH) vs. titrant volume.

Used to identify the equivalence point and reaction behavior

Types of Titration Curves

Sigmoidal Curve

Linear Segment Curve

Sigmoidal Titration Curve

Shows a gradual change before a sharp increase/decrease at the equivalence point.

Common in acid-base titrations.

Advantage: Fast and convenient interpretation of endpoint.

Linear Segment Titration Curve

Signal is proportional to analyte or titrant concentration.

Used when reactions require excess reagent to complete.

Example: Redox titrations with slow equilibrium.

Inflection Point

The point where the curve’s concavity changes.

Represents the steepest slope in the titration curve.

Marks the equivalence point in sigmoidal curves.

X-axis of a Titration Curve

The volume of a titrant added to the solution.

Y-axis of a Titration Curve

The pH of the overall solution.