Unit 4 - Cardiovascular System

1/178

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

179 Terms

What are the four primary functions of the cardiovascular system?

Distribution of blood to meet metabolic demands

enable exchange/delivery of nutrients, wastes, hormones

Role in heat regulation

Essential for hemostasis (clotting)

What are the 3 components of the cardiovascular system?

Heart - this is the pump that creates pressure to move blood through the rest of the cardiovascular system

vessels - these are the tubes the blood flows through - they include arteries, arterioles, capillaries, venules, and veins

blood - this is the fluid that carries important gases like oxygen, nutrients such as glucose, plus hormones, immune cells, protein, wastes, and more

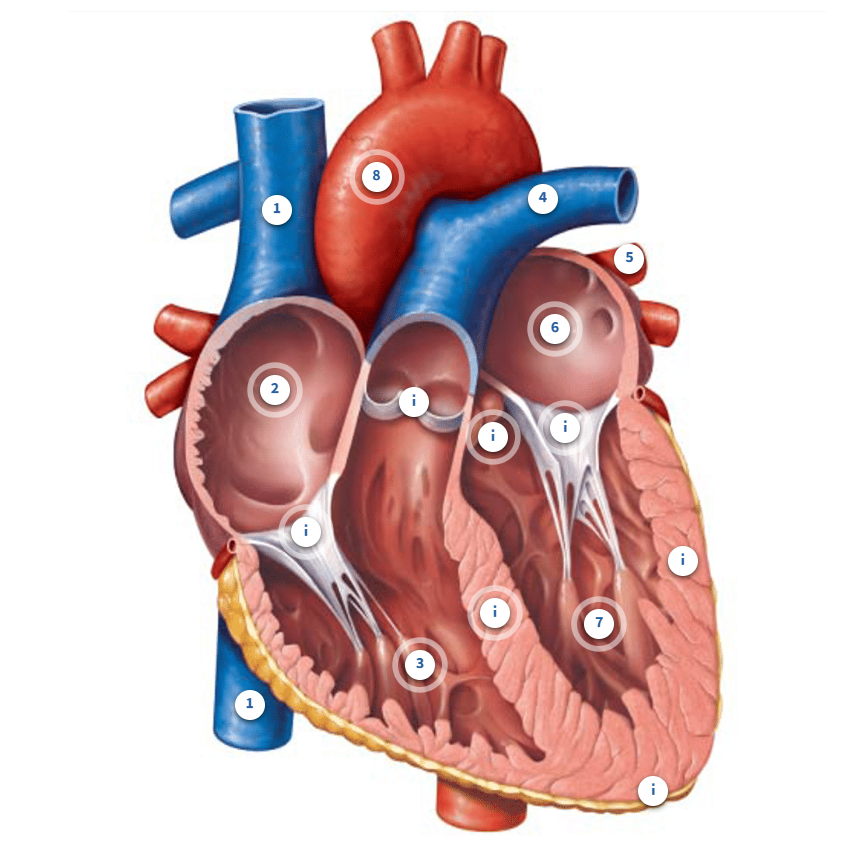

Label the heart

Superior vena cava

the vena cava is the largest vein in your body. Together with the inferior vena cava, they deliver blood back to the right side of the heart from systemic circulation. Blood in this vessel came from your neck, head, chest, and arms

Inferior vena cava

The vena cava is the largest vein in your body. Together with the superior vena cava, they deliver blood back to the right side of the heart from systemic circulation. Blood in this vessel came from your legs and feet plus abdominal and pelvic organs.

Right Atrium

Blood enters the right atrium from the systemic circuit through the vena cava (inferior and superior). Remember that this is blood that is returning from every organ and tissue in your body except your lungs. This will send blood to your right ventricle next.

Right ventricle

This chamber will fill with blood that was in the right atrium. It will send blood out of the heart, through the pulmonary arteries, and into the pulmonary circuit. Blood on this side of the heart has lower oxygen and higher carbon dioxide than the left side because it has collected blood from your systemic organs and tissues where oxygen was dropped off and carbon dioxide was picked up. This is why blood is sent to the lungs next, where it delivers carbon dioxide, a metabolic waste product which we exhale out, and oxygen is added back to the blood.

Pulmonary artery

Blood that enters the pulmonary arteries will head to the lungs, also known as the pulmonary circuit. We have a left and right pulmonary artery to deliver blood to the left and right lung. Remember that arteries carry blood away from the heart.

Pulmonary vein

This is one of the pulmonary veins. You can see another below it and two more tucked in the opposite side of this diagram. We have 2 right pulmonary veins and 2 left pulmonary veins that collect blood from different areas of the right and left lungs. These veins bring blood to the left side of the heart from the pulmonary circuit. In other words, blood that left the lungs is now returning to the left side of the heart. Remember that veins bring blood back to the heart.

Left Atrium

Blood enters the left atrium from the pulmonary circuit through the pulmonary veins. Remember that this is blood that is returning from your lungs. It will be sent to the left ventricle next.

Left Ventricle

This chamber will fill with blood that was in the left atrium. It will send blood out of the heart and into the systemic circuit. Blood on this side of the heart has higher oxygen and lower carbon dioxide than the right side because it has collected blood from your lungs. In the lungs, blood picked up oxygen and dropped off carbon dioxide in order to provide your body organs with appropriate oxygen. That is why your blood is sent out to your systemic circuit next.

What are the valves of the heart

aortic and pulmonary valves

this is where blood passes to leave the ventricles

When looking from the aorta down into the ventricle, you will notice the valve looks like three little pockets. These "pockets" are called cusps. When blood tries to move backward into the ventricle, those cusps fill up with blood, causing them to expand and close, similar to how a parachute may fill with air when skydiving. These 2 valves are sometimes called semilunar valves because of their crescent moon shape.

Atrioventricular valves

Unfortunately, these valves are also referred to by different names. To keep things simple for physiology, we will call them the AV valves since they are found between the Atria and Ventricles. Since the left and right AV valves have different anatomy from each other, they are also often called the mitral and tricuspid valves. You can see that they look different than the aortic or pulmonary valves, which we won't focus on here. What is important is that again, these valves close when blood tried to back up from the ventricle to the atrium.

what is stenosis

If valves do not open properly, a condition known as stenosis, the sound may have a higher pitch.

What are heart murmurs

If valves don't close properly, known as valve regurgitation, a swishing or whooshing sound may be detectable. We call these heart murmurs.

What are the sounds of a stethoscope

As these valves close, it changes the dynamics of blood flow which creates sound. When listening with a stethoscope, a normal heart has two dominant sounds, a "lub" and a "dub". The first sound (lub) is created by the AV valves closing, which happens when the ventricles start to contract and blood attempts to head back to the atria. The dub sound is from the aortic and pulmonary valves closing as the ventricles begin to relax and blood attempts to head back into the ventricles.

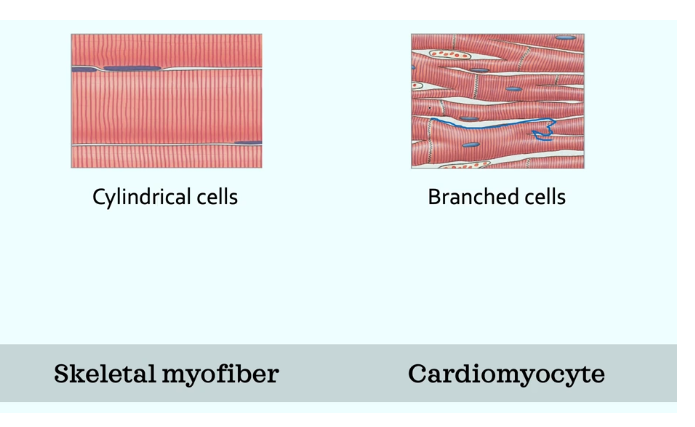

WHat are the two types of cardiomyocytes

contractile

Calcium induced calcium release - calcium from the outside made calcium release on the inside, and these are how cardiomyocytes contract

cardiomyocytes have even more mitochondria than skeleal muscle

nodal cells produce APs without neurons

branched cells

they are electrically connected through gap junctions, so cells can share information between the two which is something we dont see with skeletal muscle

they have intercalated discs - look like an egg carton - this keeps the heart cells together bwith desmosomes which is kind of the glue that keeps them together

nodal and conduction

self excitable - they make their own action potenitals to spread through heart for contraction

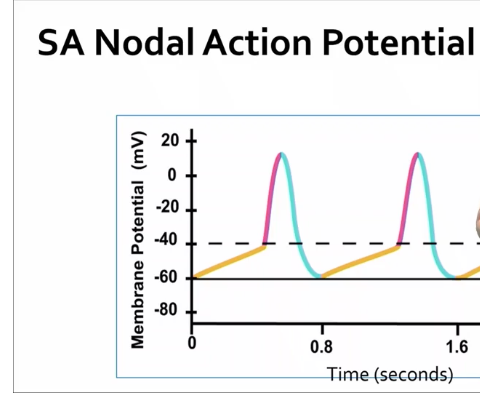

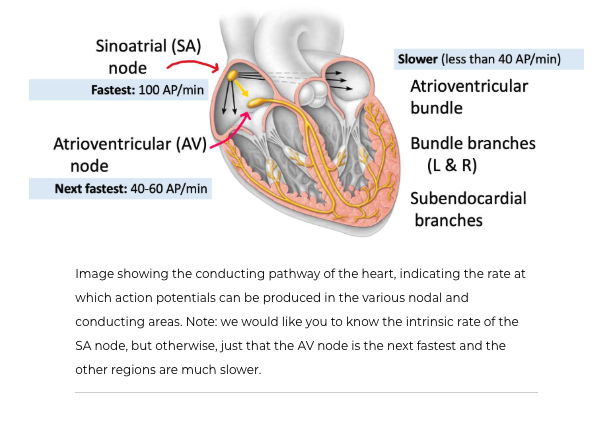

Electrical activity of the heart - how do nodal cells create action potentials

find these nodal and conducting cells at the SA node, AV node, atrioventricular bundles, subendocardial branches

SA node is found in the right atrium, and is commonly called the pacemaker of the heart because it sets how many BPM your heart is going at

SA node has no stable RMP - the lowest it gets is -60mV, and has a -40mV threshold

Sodium and calcium move into the cell to make it more positive, and we try to prevent potassium from moving out

The yellow line in the image is a graded potential called a pacemaker potential - the movement of positive ions is what causes this graded potential, and the nodal cells try to prevent potassium from leaking

Depolarization of the SA node is caused by the opening of calcium voltage-gated channels at the threshold, and then calcium moves in

in repolarization K+ moves out the cell

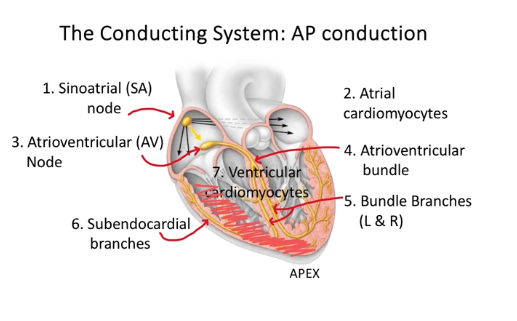

steps to a heart AP

the SA node spontasiously creates 100 APs a min even if it wasnt connected to anything, but our HR is not typically 100 BPM

due to intrinsic rate

Steps to an AP conduction in the heart

SA node fires

sends AP to atrial cardiomyocytes

then to the AV node - this provides the connection between the atria and ventricles - bit of a pause here before it gets passed in the ventricles - so it allows the atria to finish their contraction so we can get all the blood into the ventricles

to the arterioventrical bundle

then bundle branches (R and L) - travels to both the left and right ventricles so they both contract

subendocardial branches - the ap gets spread from bottom up from the apex in the ventricles, so we can squeeze the blood into the vessels out of the heart - also the AP gets really fast at this point

ventricular cardiomyocytes contraction from bottom up

What would happen if the SA node failed

If the SA node were to fail, the AV node could take over as the pacemaker, since it is the next fastest to create action potentials. This would then spread the action potential to the ventricles via the conducting system we studied earlier.

How would your HR slow down or speed up

For slower HR the NT will be working with the mucanistic receptors

when ACh binds to the mucanistic receptors from increased activation of the parasympathetic nervous sytem. this will decrease the permeability of sodium into the cell, so it takes longer to become positive, and it also allows more potassium to leak out

For a faster HR we are going to activate our sympathetic nervour system

there is a chemical response from the release of NT from the sympathetic nervous system, and these activate the androgenic receptors on the cell - the receptor will bind to the NT released by the SNS - this NT is norepinephrine - because of this, the cell becomes even more permeable to sodium and leaks out less potassium to get the cell positive quicker

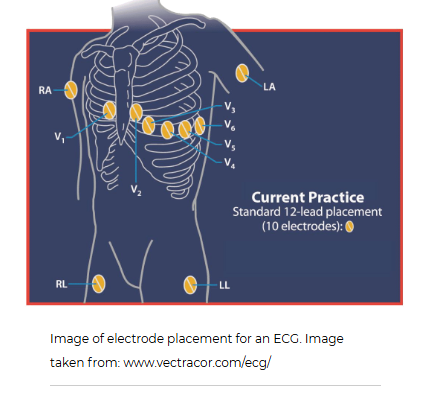

Whats an ECG

The electrocardiogram (ECG), sometimes also called an EKG, gives healthcare providers important information about the electrical activity in the heart. During this test, 10 sticky disks, known as electrodes are placed in various locations on the skin of the chest, arms, and legs. Depending on how the information is recorded, it can give 12 "views" of the heart's electrical activity from different directions. For example, from the front of the heart or sides of the heart. Therefore, it is referred to as a 12-lead ECG. It can be used to help diagnose heart arrhythmias, heart attacks, and conduction issues of the heart.

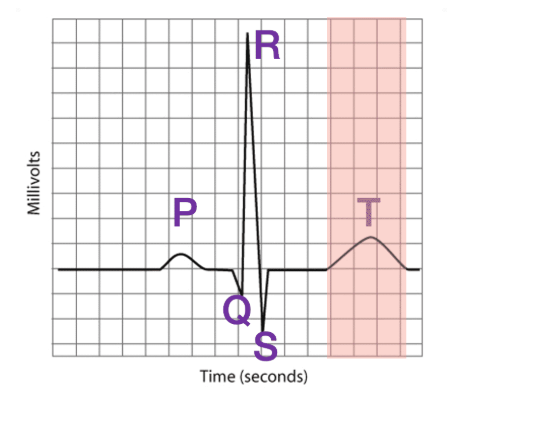

What is the P wave, QRS wave, and T wave

P wave

This electrical event is the result of DEPOLARIZATION of the atria of the heart. Please remember this is not measuring a single action potential but the sum of all action potentials occurring in the atria. If you were to measure the time from the start of 1 P wave to the next P wave, you could determine heart rate.

QRS wave

This electrical event is the result of the DEPOLARIZATION of the ventricles. Notice how much larger it is than the P wave. This is because the ventricles have a much larger mass and, therefore, more cells than the atria. With more cells comes a larger electrical event.

Measurements of the time it takes from the P wave to the start of the QRS wave (PR interval) can indicate whether electrical conduction is normal between the atria and ventricles. Other measurements, like the Q-T interval, can give indications about cardiac conditions. There are a variety of measurements that are done that are beyond the scope of this course.

T wave

This electrical event is the result of the REPOLARIZATION of the ventricles.

It is important to point out that repolarization is also "up" in the ECG. During the action potential, you have always seen repolarization as making the voltage of a cell more negative. In fact, all three of these waves (P, QRS, and T) have an upward (more positive) and then downward (more negative) component. That is because the direction of the wave (up or down) is determined by the direction of the electrical activity toward a particular electrode. If the electrical activity is heading toward that electrode, it is shown as an increase in voltage. As that electrical activity is heading away from that same electrode, it measures a decrease in voltage. It is more complicated than this, but hopefully this makes sense. In other words, do not confuse what is seen in the ECG to what you learned about for action potentials. Again, these are not individual action potentials.

Wait, what about the atria? If they depolarize, why don't they also repolarize?

Well, they do. The atria repolarize at about the same time as the QRS wave. And because the atria are smaller, their repolarization is masked by the large QRS activity as the ventricles are depolarization. So we don't see a unique wave created by atrial repolarization like we do for ventricular repolarization.

From an ECG, cardiac arrhythmias, a myocardial infarction (heart attack), damaged heart muscle, conduction problems, and a host of other cardiac conditions can be detected.

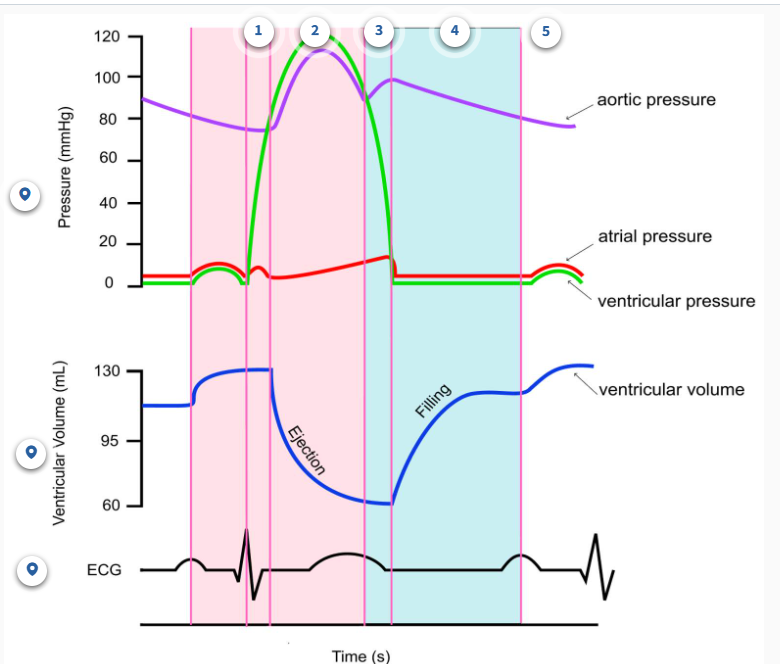

What are the 5 phases of the cardiac cycle

Isovolumetric ventricular systole: this is when the ventricles start contracting but they aren't yet able to pump blood out of the heart. Hence the term isovolumetric is used, as the volume of the ventricles don't change. Iso means equal in Greek.

2

Ventricular systole: this is when the ventricles are contracting AND moving blood out of the heart and into the aorta (L ventricle) or pulmonary arteries (R ventricle).

3

Isovolumetric ventricular diastole: this is when the ventricles start relaxing but they aren't yet able to fill with blood. Again, notice the word isovolumetric here since ventricular volume isn't changing.

4

Late ventricular diastole: this is when the ventricles are relaxing AND starting to fill with blood from the atria.

5

Atrial systole: this is when the atria are contracting, moving blood into the ventricles.

Ventricular systole: 2 phases

Phase 1: isovolumetric ventricular systole

in this phase, the QRS wave occurs, and this is because there is a delay between the electrical impulse vs the actual contraction

there is no change in volume

the valves are not open

there is a large increase in ventricular pressure

Phase 2: Ventricular systole

this is where ventricular pressure becomes higher than aortic pressure

the aortic valve is open, and the AV valve is closed

decrease in volume of the ventricles

this is where the volume of the ventricles is at its lowest, but its important to note that the heart never fully empties

Ventricular diastole: 2 phases

🔄 Phase 3: Isovolumetric Ventricular Diastole

🫀 All valves are closed

⬇ Ventricular pressure decreases (ventricle is relaxing)

⬆ Aortic pressure remains high

🔁 No change in ventricular volume (iso = same)

📉 T wave from Phase 2 continues and ends here

💧 Phase 4: Late Ventricular Diastole (Passive Filling)

📈 Ventricular volume increases (filling with blood)

✅ AV valve is open (due to low ventricular pressure)

❌ Semilunar valves are closed

📉 Ventricular pressure < Atrial pressure

📉 Aortic pressure slightly decreases

➖ Flat ECG line (no electrical activity)

💓 Phase 5: Atrial Systole (Atrial Contraction)

📈 Further increase in ventricular volume (final bit of filling)

✅ AV valve remains open

⬇ Ventricular pressure still low, but rising slightly

⬆ Atrial pressure increases (due to contraction)

🔺 ECG: P wave begins in Phase 4, completes here

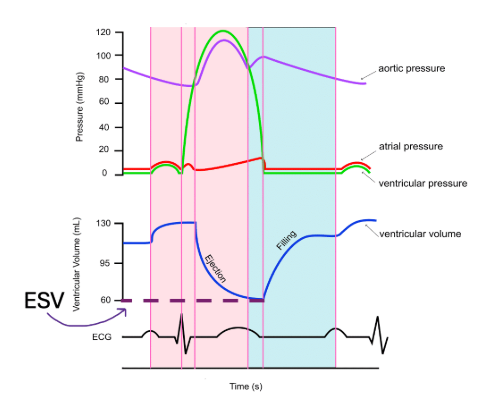

End systolic volume (ESV)

is the amount of blood remaining in the ventricles at the end of systole (hence the name) after the ventricles have contracted. It indicates the efficiency of the heart's pumping ability. A lower ESV typically means the heart is contracting more effectively, while a higher ESV may indicate heart dysfunction.

In the diagram below, ESV is equal to 60 mL. You do not need to memorize this number.

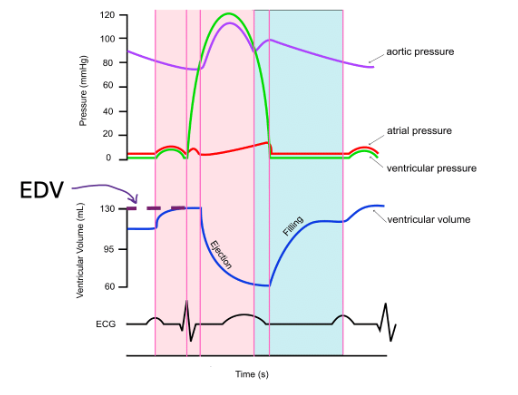

End diastolic volume (EDV)

is the amount of blood in the ventricles just before ventricular contraction. Remember, the ventricles have the maximum volume after ventricular diastole once the atria have finished their final "top up" during atrial systole before the ventricles start contracting again. So, here the name makes sense again!

In the diagram below, EDV is about 130 mL. Again, you do not need to memorize this number.

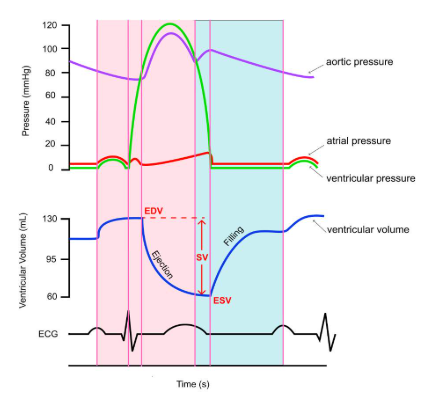

Stroke volume (SV)

Stroke volume (SV) is the amount of blood pumped out or ejected by the ventricles with each heartbeat. Stop for a moment and consider how you might calculate how much blood leaves the heart. Think about the two volumes (EDV and ESV) we have discussed already.

If we know how full the ventricle was (EDV) and how much remained after it contracted (ESV), we can easily determine how much blood left the ventricle in that heartbeat. It is calculated by subtracting the end systolic volume (ESV) from the end diastolic volume (EDV). Therefore, an increase in EDV or a decrease in ESV can lead to a higher stroke volume. Looking at this as an equation:

SV = EDV - ESV

In the diagram below, stroke volume would be calculated to be 70 mL, since EDV is 130 mL and ESV is 60 mL on this graph.

Stroke volume is an important indicator of heart health as it influences a person's cardiac output, which we will discuss next. Stroke volume is affected by several factors, including preload and cardiomyocyte contractility. We will look at how these two factors influence stroke volume shortly.

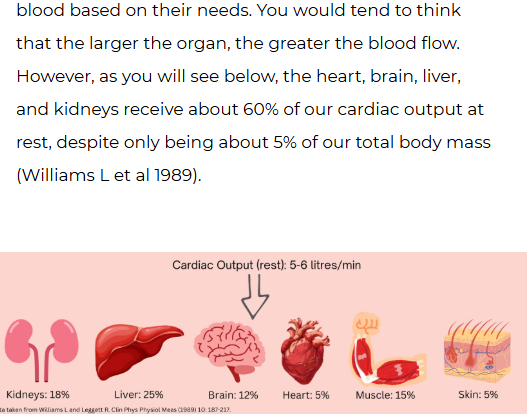

Cardiac Output (CO)

Cardiac output (CO) is the amount of blood the heart pumps per minute. This is often what is used clinically as a measure of heart function and overall cardiovascular health. Cardiac output is determined by two main factors: heart rate and stroke volume.

Heart rate refers to the number of times the heart beats per minute, while stroke volume is the amount of blood pumped with each beat. Therefore, to calculate this:

CO = HR x SV

For example, if someone's heart rate is 70 beats per minute and their stroke volume is 70 mL, their cardiac output would be 4900 milliliters per minute, or 4.9 liters per minute. A typical cardiac output at rest is about 5 - 6 litres per minute.

Cardiac output is essential for maintaining adequate blood flow to all your tissues and organs. It ensures that proper oxygen and nutrients are delivered to cells, and waste products are removed. Without sufficient cardiac output, the function of organs and tissues will be impaired.

Keep in mind that anything affecting heart rate or stroke volume will impact cardiac output.

What controls stroke volume

ANS Innervation

the SA node has muscarinic and androgenic receptors

sympathetic - innervates ventricular cardiomyocytes by norepinephrine/epiniephrine binding to androgenic receptors

the NT (nor) or hormone (epi) bind to andregenic receptors and create a larger stroke volume because as they bind they increase calcium permeability, so this increases the strength of contraction

parasympathetic - only some innervation to contractile cardiomyocytes by ACh binding to muscarinic receptors

this decreases calcium permeability so less CA2+ goes out from the SR into the cytoplasm

Preload on the heart (EDV)

because of frank sterling’s law if we increase the volume in the ventricle we will still end up with the same ESV, so if we put in more we get a bigger SV

what is the distribution of blood volume between our pulmonary and systemic circuit

pul - 15%,

sys 85%

arteries - 10%

capillaries - 5%

veins - 70%

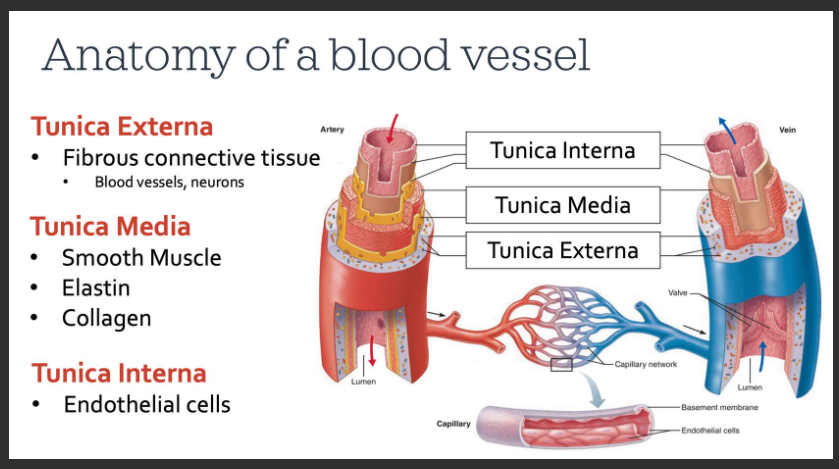

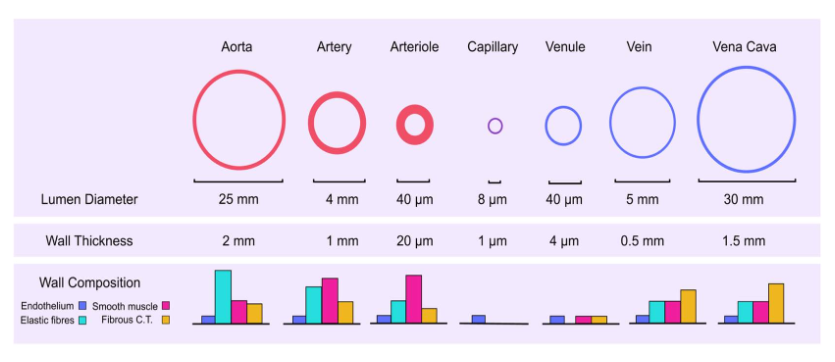

What is the anatomy of a blood vessel

blood passes through the center of the tube called the lumen - similar to looking at the top of a paper towel roll

Tunica externa: this is the outermost layer composed mostly of connective tissue which functions to protect the vessel, adhere it to surrounding tissues, and maintain its appropriate structure. We can find neurons of the sympathetic nervous system, which communicate with the tunica media beneath this layer. In larger arteries and veins, we even find blood vessels in this layer. This ensures that the cells making up the walls of these vessels receive proper oxygen and nutrient delivery. It probably seems odd to think that blood vessels can have blood vessels too!

Tunica Media: this is the middle layer that contains smooth muscle, which like skeletal muscle, can contract or relax to various stimuli. Smooth muscle will change the diameter and, thus, the size of the lumen of the vessel. There are also elastic fibres, called elastin. Elastin allows vessels to stretch and recoil back to their resting shape, much like an elastic band would. We also find collagen here, a protein that is common in connective tissue. Different types of blood vessels differ in their proportion of smooth muscle, elastin, and collagen in their tunica media as you will see.

Tunica Interna: this is the innermost layer, composed of special cells that line all blood vessels. These cells are known as endothelial cells. This layer is important for normal vessel function.

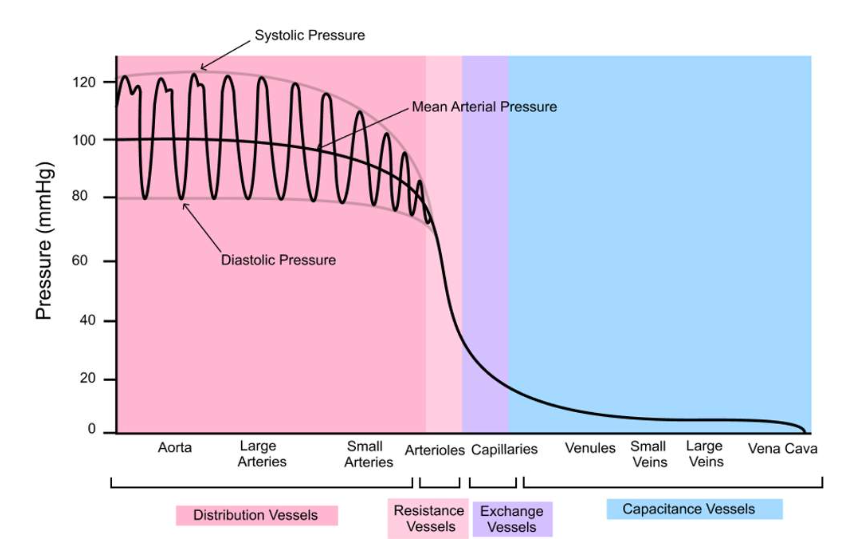

Pressure distribution of arteries and veins

How vessels differ: Structure and function

Arteries: These vessels are tasked with carrying blood away from your heart to the various organs and tissues of your body. Therefore, we refer to them as distribution vessels. These are large diameter blood vessels, and their wall is about 25% as thick as their diameter (Fig. 1). They have a lot of elastin in their walls, enabling them to stretch much like an elastic band would. This is important since they are receiving blood during ventricular systole, requiring them to stretch, but can then recoil or "unstretch" during ventricular diastole to keep moving blood through the cardiovascular system. Otherwise, blood flow would be disrupted during diastole when the heart is relaxed. Compared to smooth muscle, elastin is the most abundant structure in the tunica media of arteries.

Arterioles: These are smaller than arteries, but notice that relative to their diameter, they have thick walls. Their wall is about 50% as thick as their diameter, much more than arteries (Fig. 1). These thick-walled vessels are often referred to as our resistance vessels due to the vast amount of smooth muscle, rather than elastin, that dominates their tunica media. This smooth muscle can contract and relax to various stimuli so that the lumen diameter can become smaller or larger, respectively. You see a huge drop in blood pressure here (Fig. 2). We will discuss why that happens later on, but it is related to their overall resistance to blood flow.

Capillaries: These are our smallest blood vessels, composed of only a single layer of endothelial cells. As you can see, they have extremely thin walls (1 um = 1/1000 mm) (Fig. 1). Their purpose is to act as exchange vessels. Oxygen will leave the blood and enter the cells of your tissues and organs, and so will nutrients, and ions. Hormones will leave capillaries to bind to their receptors on target cells, along with other small molecules. Blood will also pick up wastes like carbon dioxide and many others, so our body can eliminate them. Blood pressure is lower in these vessels than in arterioles (Fig. 2)

Venules: Blood leaves capillaries and flows into these vessels next. In order for blood to flow, the pressure in the venules has to be lower than in capillaries. We won't look at these vessels in any more detail.

Veins: These vessels carry blood back to our heart from your organs and tissues. As you saw at the start of this session, they happen to contain the majority of our blood volume (70%). Therefore, we refer to them as capacitance vessels, because they have the capacity to hold blood. These are large diameter but thin-walled vessels. Their wall thickness is only about 10% relative to their diameter (Fig. 1). This probably makes sense since the blood flowing through them has a very low pressure, unlike arteries (Fig. 2). They don't need such thick walls to be able to withstand the high pressures that arteries do!

what is the distribution of cardiac output at rest

Arteries structure, blood characteristics and purpose

distribution vessels

structure

large diameter

thin walls compared to diameter

lots of elastin fibres

easy to stretch

blood characteristic

very high blood pressure

pulsatile with very small drop in pressure

purpose

shock absorbers

Arterioles structure, blood characteristics and purpose

Resistance vessels

structure

small diameter

thick walls compared to diameter

lots of smooth muscle

smooth muscle innervated by SNS

blood characteristics

large drop in pressure since lots of resistance

purpose

controls blood flow (vasoconstriction, vasodilation from the tunica media)

What is the blood flow equation

bf = pressure gradient / resistance

R = Ln/r4 R= resistance, L = length, n = viscosity, and r4 = radius

What are the mechanisms used to regulate blood flow

local (intrinsic) - tissue environment (temp, gases, pressure)

these mechanisms involve changes in the conditions of the organ or tissue itself. We say they are INTRINSIC mechanisms since the stimulus to change blood flow comes from within the very tissue or organ that needs it.

humoral (extrinsic) - Substances in blood)

these mechanisms involve substances that are travelling in the blood through the blood vessels of the tissue/organ. These substances will change the radius of the blood vessels, often by binding to receptors that recognize that substance. Some substances will cause vasodilation and others will cause vasoconstriction. Often this type of regulation involves hormones produced elsewhere in the body. Therefore, we consider this to be a type of EXTRINSIC mechanism, since the signal to change blood flow came from outside the tissue/organ.

Neural (extrinsic) - nervous system

neurons from the sympathetic nervous system innervate the smooth muscle cells found in the tunica media of many of our blood vessels. These neurons release the neurotransmitter norepinephrine that you saw in session 2. Norepinephrine binds to adrenergic receptors to cause vasoconstriction which will reduce blood flow. This is also an EXTRINSIC mechanism since the neurons originate from outside of the tissue/organ.

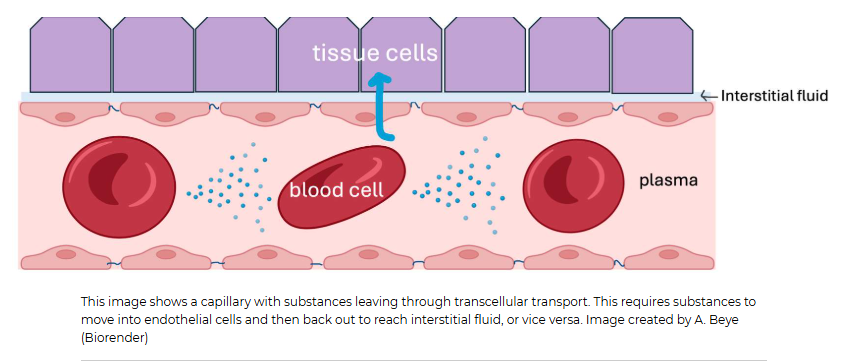

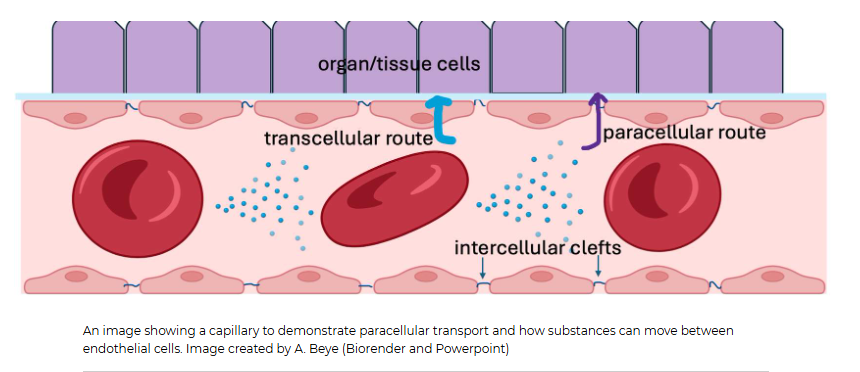

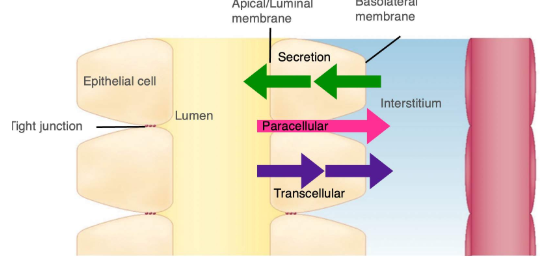

How does movement occur in the capillary, and what are the two kinds of plasma membranes

Movement may be from the plasma within a capillary out to the interstitial fluid surrounding a capillary, or from the interstitial fluid back into the plasma. As seen in the diagram below, substances passing through the endothelial cell actually have to encounter TWO plasma membranes, the one closest to the capillary lumen, called the luminal membrane, and the one closest to the interstitial fluid, called the basolateral membrane. You can think of this as the cell having a "top" and a "bottom".

Substances moving across the epithelial cell this way use transcellular transport, meaning the substance has to actually enter and then exit the endothelial cell.

What kind of transport occurs between two endothelial cells lining the capillaries

This type of transport is called paracellular transport. Para in Greek means beside. We tend to refer to this type of movement as bulk flow since fluid and anything dissolved in it (ions, hormones, glucose, wastes, drugs) that are small enough to fit through that intercellular cleft will flow through it. Bulk flow isn't very selective apart from size. This is one reason why the ion concentrations between the plasma and interstitial fluid are very similar! Proteins, on the other hand, cannot fit through these clefts. That is why the interstitial fluid has different protein concentrations than the plasma does.

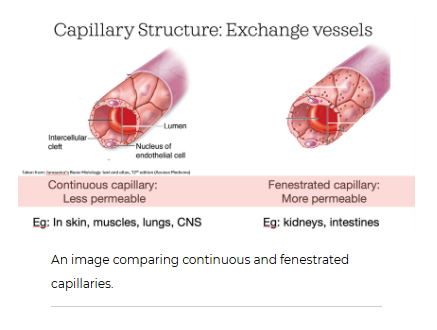

What are the 3 types of capillaries we have in our bodies

We have a few different types of capillaries in our body. Continuous capillaries are the most abundant capillaries. But we also have fenestrated capillaries, found in the kidneys and intestines, and sinusoidal capillaries of the liver and spleen. These different capillaries have different permeability or "leakiness" to bulk flow.

Continuous capillaries are much less permeable than fenestrated capillaries. Both capillaries have intercellular clefts, which you learned about above. These small slits are found at the border where two endothelial cells meet. But

fenestrated capillaries also have pores that go directly through the endothelial cell. These fenestrations are a bit like tunnels that allow substances to pass from inside the capillary directly into the interstitial fluid surrounding it.

Continuous capillaries

These are found in our muscles, brain, lungs, heart, and many other organs. Continuous capillaries themselves can also vary in their permeability or leakiness. Some have wider intercellular clefts between endothelial cells while others have almost none at all. The brain is a great example of continuous capillaries with almost no permeability through intercellular clefts. This is important because if we had a lot of fluid leak out of capillaries in our brain, this could lead to problems as it is encased in a hard bony skull and can't expand!

The permeability of the intercellular clefts is related to proteins responsible for linking two endothelial cells together. These proteins form tight junctions. The "tighter" the tight junction, the narrower the intercellular cleft, like in the blood-brain barrier. The size of these clefts will determine what substances can pass in between cells and which can't. This is much like a kitchen colander/strainer that will allow water and salt to pass through it, but not the spaghetti noodles you may make for dinner! Cells and proteins typically cannot pass through these clefts.

What is the role of the lymphatic system in regards to capillary filtration?

they are vessels that return ISF to the circulation, because we always get more filtration than reabsorption, so the lymphatic system helps out with that.

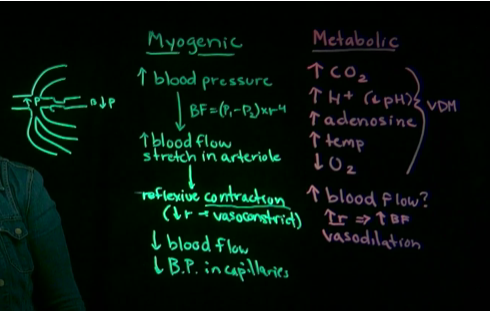

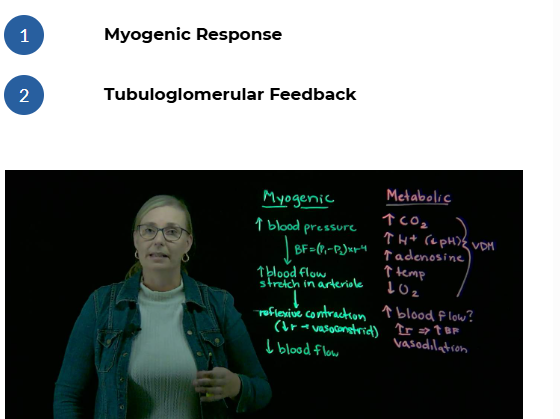

What are the two autoregulatory mechanisms for local regulation

myogenic theory

Muscle stretch

this means that the tissue itself can dictate how much fluid is coming through by changing the radius on the vessels

increased BP will caused increased stretch in arteriole which them would casue a reflexive contraction to reduce radius (vasoconstrict)

this will cause a dropin blood flow because this theory means theres too much blood going into this tissue

metabolic theory

metabolic needs

increased CO2, H+, adenosine, temp

decreased O2 because it is using more

this tissue is more metabolically active

so the vessels have to change radius to supply more blood flow (vasodilation)

Humoral regulation of blood flow

Substance | Source | Mechanism | Trigger |

|---|---|---|---|

Epinephrine | Adrenal glands | Binds to α-adrenergic receptors → smooth muscle contracts → vasoconstriction | Sympathetic activation |

Angiotensin II | Liver → kidneys → blood | Binds to vascular smooth muscle → vasoconstriction | Low blood pressure |

Antidiuretic Hormone (ADH) aka Vasopressin | Posterior pituitary | Binds to smooth muscle in vessels → vasoconstriction; also promotes water retention in kidneys | Low blood pressure |

Vasodilation

Substance | Source | Mechanism | Trigger |

|---|---|---|---|

Histamine | Inflammatory cells | Binds to vessel receptors → vasodilation → increased immune cell delivery | Allergic/inflammatory response |

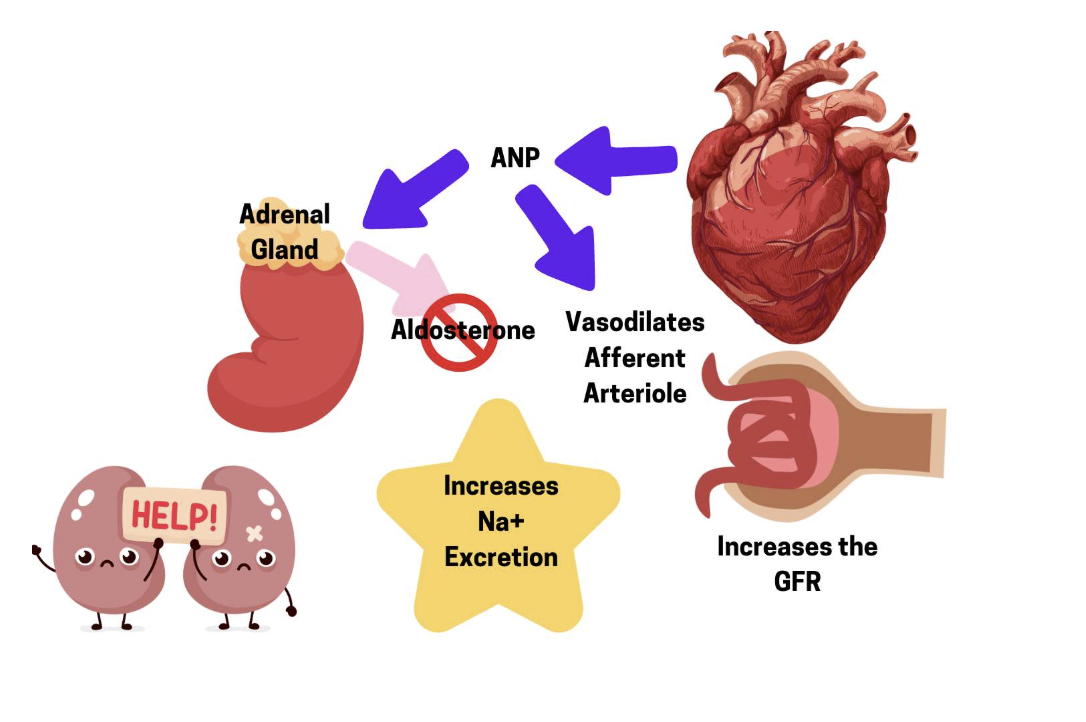

Atrial Natriuretic Peptide (ANP) | Atria of the heart | Relaxes smooth muscle → vasodilation | High blood pressure |

Epinephrine | Adrenal glands | Binds to β-adrenergic receptors → vasodilation in skeletal muscles | Sympathetic activation (target-specific) |

Same hormone (epinephrine) can cause vasoconstriction or vasodilation depending on receptor type:

α-receptors → vasoconstriction

β-receptors → vasodilation (e.g., skeletal muscle arterioles during fight-or-flight)

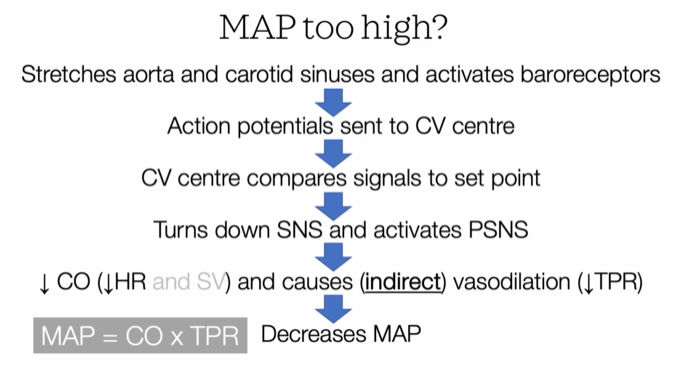

How do we calculate mean arterial pressure

MAP is the average pressure of the arteries, and since the arteries spend more time in diastole, the equation is

MAP = diastolic pressure + 1/3 (systolic pressure-diastolic pressure)

MAP = CO x TPR

if cardiac output or total peripheral resistance changes, then this can affect the MAP

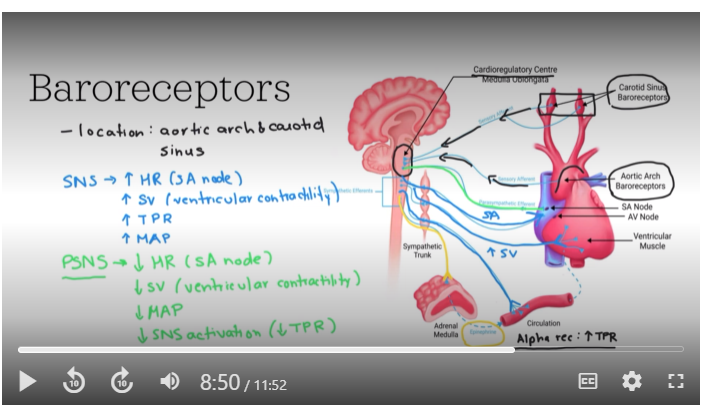

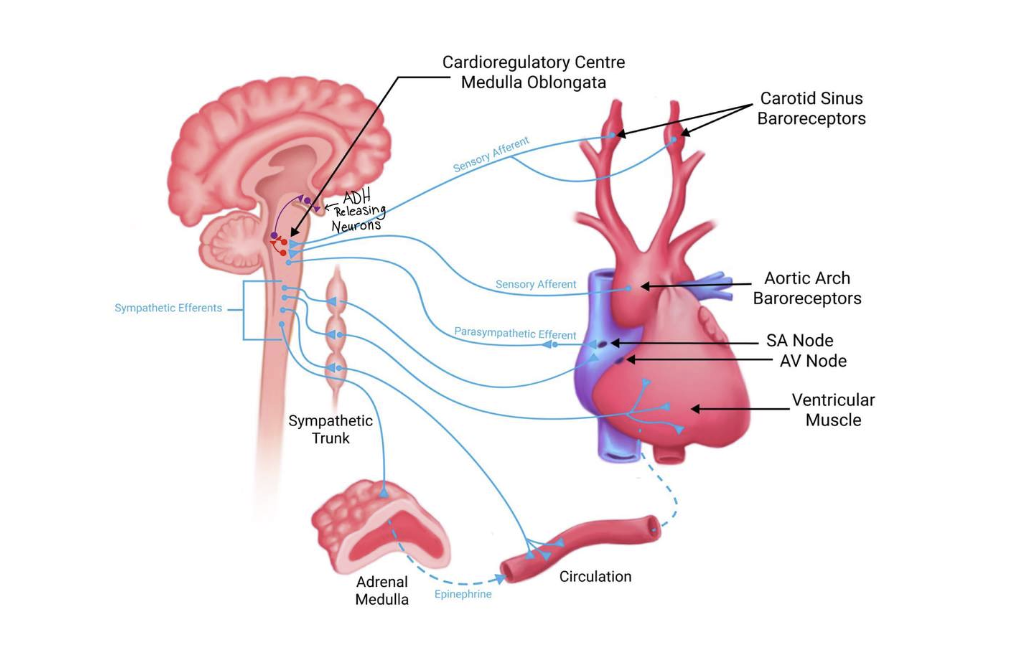

Baroreceptor Reflex and MAP

he negative feedback system used for blood pressure homeostasis is called the baroreceptor reflex. It is critical for maintaining mean arterial pressure (MAP) within a narrow range, ensuring stable blood pressure and appropriate blood flow. Stretch receptors, known as baroreceptors, detect changes in blood pressure and send signals to the medulla oblongata of your brainstem. This initiates a negative feedback loop that adjusts heart rate, stroke volume, and blood vessel diameter to stabilize MAP.

When mean arterial pressure deviates from the normal set point, the reflex quickly counteracts these changes, preventing potential damage from prolonged hypertension or hypotension. These fast changes involve activation of the parasympathetic or sympathetic nervous system

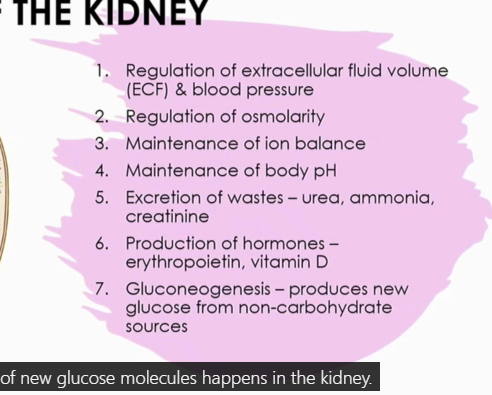

What are the 7 functions of the kidney

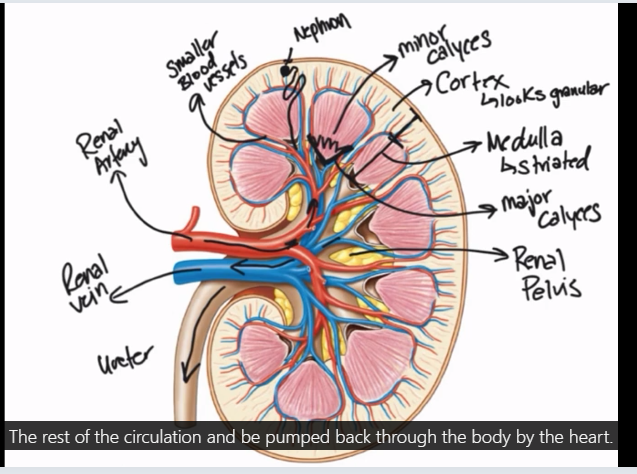

Anatomical structure of the kidney

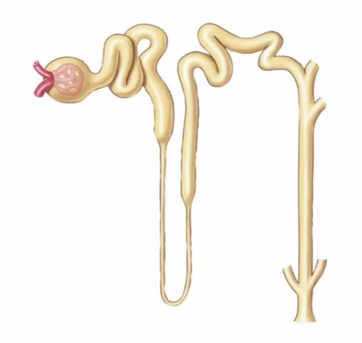

Label the nephron

often have 4-5 nephrons connecting to one connecting duct

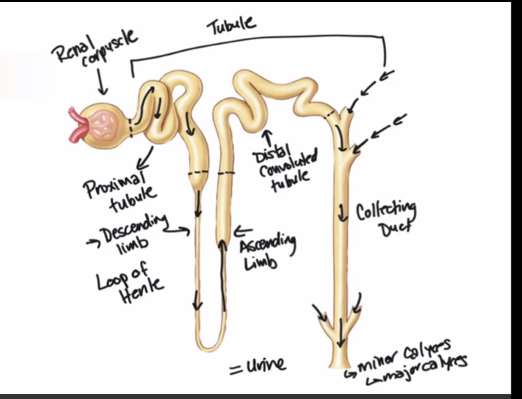

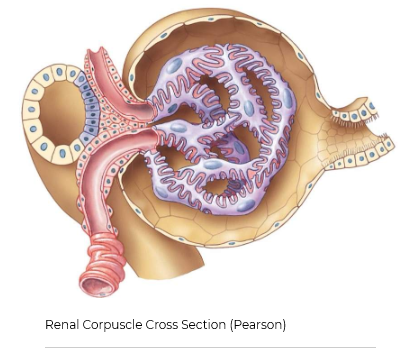

The Renal Corpuscle

The renal corpuscle is the part of the nephron that filters blood and produces a fluid called the filtrate and is made up of three components…

1

Bowman's Capsule - Where fluid filters into

2

Glomerulus - Specialized leaky capillaries

3

Juxtaglomerular Apparatus (JGA) - Junction of the tubule and arterioles around Bowman's capsule

is a fluid-filled hollow ball-like structure that surrounds the glomerulus. The capsule is continuous with the beginning of the first part of the tubule, which is termed the proximal tubule. The cells that make up the outside of Bowman’s capsule are simple flattened-looking cells called epithelial cells (shown in yellow in this image). The cellular part of Bowman’s capsule that physically contacts the glomerulus is a specialized type of epithelial cells called podocytes (shown in purple).

Another important structure is the juxtaglomerular apparatus (JGA). The JGA is composed of the junction of a part of the tubule that is called the late ascending limb of the loop of Henle, which passes in between the two blood vessels that enter and exit the corpuscle called the afferent and efferent arterioles. Specialized cells in the late ascending limb of the loop of Henle are called macula densa cells. These cells can detect the concentration of sodium and chloride in the filtrate as it passes through the tubule. The cells just beside the macula densa are called the juxtaglomerular cells (also known as granular cells), which are responsible for producing and releasing an important enzyme called renin. The function of renin will be discussed in upcoming sessions.

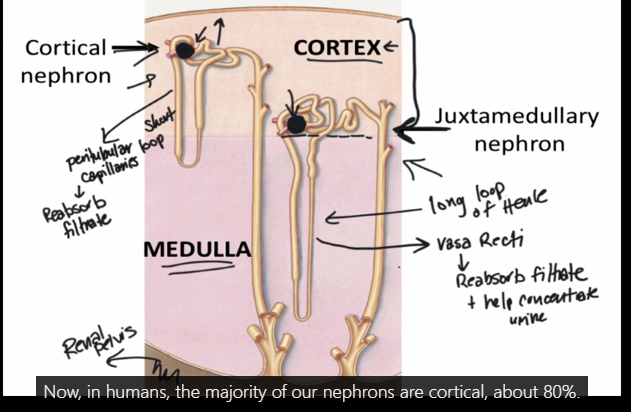

What are the two types of nephrons, and what are their differences?

Nephrons are positioned in two different ways within the layers of the kidney. Nephrons are categorized based on this positioning and some anatomical differences, as being either a cortical nephron or juxtamedullary nephron. Both nephron types still filter blood similarly, and both process the fluid that is filtered in much the same ways as the filtrate fluid passes through the tubule segments.

Humans have many more cortical nephrons than juxtamedullary nephrons. Approximately 80% of all nephrons in a human kidney are categorized as cortical, whereas 20% are juxtamedullary. The ratio of the two types of nephrons varies between species. There are some key anatomical differences between these two types of nephrons that result in the additional ability of juxtamedullary nephrons to conserve more water.

jux has a long loop of henle

cortical has peritubular loop capillaries- job is to reabsorb filtrate

jux are crucial for concentrating urine and conserving water. They are characterized by their location near the medulla and their long loops of Henle, which are essential for creating the conditions needed for urine concentration

Blood flow to the kidneys

20% of CO goes to the kidneys

afferent arteriole

brings blood to the kidney

Glomerulus

capillary bed inside of the corpuscle

efferent arteriole

takes blood away from kidneys

Pertibular capillaries - vasa recti for the jux nephron*

wrap around the tubule

respinsible for reabsorption

venule

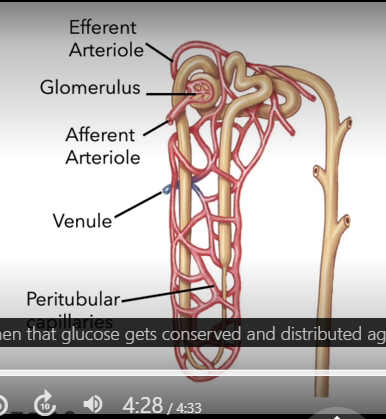

Processes of the Nephron

Our kidneys produce 180 litres of filtrate per day. However, we only excrete approximately one and a half to two litres of urine a day. Therefore, most of the filtrate that is created must be reabsorbed back into our body so that it is not excreted as urine. Three processes of the kidney will affect how much fluid and what in that fluid is excreted (E); filtration (F), reabsorption (R) and secretion (S).

Filtration

The movement of fluid and the items dissolved in the blood from the glomerulus into the space of Bowman's capsule is called "Filtration". The fluid that enters Bowman's space is called filtrate. Filtration is a process that only occurs with the renal corpuscle.

Reabsorption

The movement of items from the filtrate within the tubule back into the surrounding capillary bed is called reabsorption. Most of the fluid that is originally filtered, is reabsorbed. Contents of the filtrate that are reabsorbed include water, ions, glucose and amino acids. The capillary bed that surrounds the tubule of a cortical nephron is the peritubular capillaries. These capillaries are very similar to the vasa recti capillary bed that surrounds juxtamedullary nephrons.

secretion

Items dissolved in the blood can also be added into the filtrate as it travels through the tubule. The movement from peritubular (or vasa recti) capillaries is called secretion. These are items that may not have had an opportunity to be filtered within the corpuscle and often include medications that our body is trying to remove at a quicker rate than these items can be normally filtered within the corpuscle.

Excretion

The filtrate that is collected in the renal pelvis, and then collects in the bladder is called urine. Urine is what is excreted from the body and the production of urine is called Excretion (E). The contents of urine is due to the earlier processes within the nephrons; Filtration (F), Reabsorption (R) and Secretion (S). The items excreted in urine are therefore due to how much of each item that was filtered, minus how much of that item was reabsorbed plus any more of that item that was secreted into the tubule.

Formula for Excretion

Filtration (F) - Reabsorption (R) + Secretion (S) = Excretion (E)

In other words:

In order to be excreted in urine, the item (ie solute) must be first filtered (F). If the item is then reabsorbed (R), it is therefore not excreted, so that is subtracted from the formula. If an item is secreted (S) into the filtrate (and not subsequently reabsorbed again), it will be part of what is excreted.

What are filtration barriers

🧱 Filtration Barriers in the Glomerulus 💧 What is Filtration?

Filtration occurs in the renal corpuscle, where blood is filtered from the glomerulus into Bowman's space. Although the glomerulus is leaky due to pores (fenestrations), not everything in blood can pass through.

🧬 Why Doesn’t Everything Get Filtered?

Despite the glomerulus being porous:

Red and white blood cells are too large to pass.

Proteins are restricted due to multiple layers of selective barriers.

🧱 The 3 Filtration Barriers

Barrier | Structure | Function |

|---|---|---|

1. Endothelial Cells | Inner lining of glomerular capillaries (fenestrated) | Pores allow most solutes through, but not cells |

2. Basal Lamina | Sticky extracellular matrix made of collagens and negatively charged glycoproteins | Prevents proteins from entering Bowman’s space |

3. Podocytes | Specialized cells with pedicels (finger-like projections) forming narrow filtration slits | Regulate how much fluid passes into Bowman’s space by changing slit width |

🧠 Summary

The glomerular filter = endothelial pores + basal lamina + podocyte slits.

All three barriers work together to allow fluid and small solutes through, while blocking cells and proteins.

A full urinalysis generally has three types of measurements:

VISUAL INSPECTION - Although normal/healthy urine should be a light yellow colour, many other colours can be observed (such as green, blue, brown, and red) which may or may not cause concern. Clear urine indicates that a person is likely overhydrated, whereas urine that is much darker yellow can indicate dehydration. Urine should also be clear, and if particles or frothing are observed, these suggest issues such as early signs of kidney stones (particles observed), and the presence of bacteria (milky) or proteins (frothy) in the urine.

MICROSCOPIC EVALUATION - Early signs of kidney stones can be diagnosed if sediments and/or small crystals are observed in the urine sample. Bacteria can be visualized using microscopic evaluation, which would confirm a urinary tract infection. If red blood cells are also observed together with bacteria, this usually indicates a urinary tract infection. However, there are other causes of red blood cells in the urine, such as types of urinary tract cancers. The cause of the red blood cells in urine requires more extensive evaluation to rule out a cancer diagnosis.

CHEMICAL ANALYSIS - Most urine test strips will test for items such as glucose, proteins, bilirubin, ketones and white blood cells (leukocytes). For these measurements, we expect to see no presence of any of these in healthy urine. We will learn in later sections, that although glucose can easily filter into Bowman's space, no glucose should be observed in urine. If glucose is observed in urine, this can indicate that the patient has diabetes mellitus.

What are the 4 net filtration pressures

Hydrostatic Pressure of Glomerular Capillaries (PGC) - Blood is pushed through the vessels of the body by the pump of the heart. As the blood flows through the leaky glomerular capillaries, the fluid is forced into the capsule space. This pressure favours filtration and is generally the largest force that promotes filtration.

Colloid Osmotic Pressure of Glomerular Capillaries (πGC) - Proteins dissolved in the blood plasma are mostly incapable of filtering into the capsular space due to size and charge. Water has an affinity for proteins, and therefore the proteins generate a force, drawing water to where the proteins flow. The result is a force that inhibits filtration as the proteins stay in the glomerular capillaries.

Hydrostatic Pressure of Bowman’s Capsule (PBC) - As fluid filters into the capsular space, it fills the capsule. Although fluid can exit the capsule, its movement out is slow through the first part of the tubule. The back pressure of fluid in the capsule limits more fluid from filtering into the capsule space. The presence of filtrate therefore is a force that inhibits fluid filtration.

Colloid Osmotic Pressure of Bowman’s Capsule (πBC) - If proteins were able to filter into the capsular space, the protein would pull fluid with it. This is a positive force that favours filtration, although it usually doesn’t exist due to the restriction of most proteins from filtering into the capsular space. Sometimes this pressure is ignored since its force is usually a value of 0 mmHg. However, if proteins were to filter, such as in the pathology of the nephrons, the force would result in favouring fluid filtration.

Net filtration pressure = (PGC + πBC) - (PBC + πGC)

in a healthy person we dont see proteins filter from the capillaries that go into the glumerulus into bowmans space because of the hydrostatic pressure inside bowmans space

What are the two types of autoregulation for the GFR

Myogenic Theory

Recall from the cardiovascular section of the course that you have already learned about the myogenic theory.

When blood pressure increases in a blood vessel, that will cause an increase in blood flow and therefore stretch of an arteriole. The response is a reflexive contraction of the smooth muscle within an arteriole. The blood flow after this vasoconstriction is reduced.

The same response occurs in the kidneys. When blood flow increases to each nephron, this will increase pressure within each glomerulus and increase the GFR. The myogenic response will function to reduce the GFR, to keep it fairly constant. The myogenic response in the kidneys is a reflexive contraction of the afferent arteriole. The blood flow into each glomerulus will then be reduced, bring the GFR back down.

Tubuloglomerular Feedback

The actual content of the filtrate can also regulate the GFR locally. As mentioned earlier, the tubule of a nephron, twists upon itself: the late part of the ascending limb of the loop of Henle passes between the afferent and efferent arteriole. The macula densa is the name given to the cells found at this specialized junction. The macula densa cells detect the salt composition of the filtrate and detectors and the rate of fluid flow. If blood pressure increases, this will cause an increase in how much fluid is filtered. A consequence of that is an increase in the amount of solute like Na+ and Cl- being filtered. When Na+ and Cl- levels in the filtrate are too high, or when fluid flow is too high, the macula densa cells release a paracrine factor that stimulates the afferent arteriole specifically to constrict and therefore reduce the rate of fluid filtration.

What happens when blood pressure increases for the GFR

GFR increases - When blood pressure increases, this will increase the amount of fluid being filtered into Bowman's space.

Increased filtrate flow & filtrate salt content - When more fluid is being filtered to produce filtrate, that filtrate will flow through the tubule at a faster-than-normal rate. The filtrate will also contain more dissolved substances, which include "salt" (sodium and chloride ions).

Filtrate flow through the juxtaglomerular apparatus - The filtrate will continue to move through the tubule, through the ascending limb of the loop of Henle. The last part of the ascending limb of the loop of Henle is part of the juxtaglomerular apparatus. Part of the apparatus are the macula densa cells, which are able to detect the rate of filtrate flow and the salt composition of the filtrate.

Macula Densa Cells - These cells can detect how fast filtrate is flowing past them. These cells can also detect how much salt (sodium and chloride) is in the filtrate. When the filtrate is moving faster than usual, or if the filtrate contains more salt, macula densa cells release a chemical messenger (paracrine factor) called adenosine.

Afferent Arteriole response - If macula densa cells release adenosine, this chemical messenger will cause the smooth muscle cells of the afferent arteriole to contract. The contraction will cause a reduced diameter of the afferent arteriole. When the afferent arteriole diameter is reduced, less blood can now flow into the glomerulus. When less blood is moving into the glomerulus, less fluid is filtered. This returns the GFR to "normal".

However, when blood pressure decreases, the tubuloglomerular feedback response is the opposite. If blood pressure decreases, and the GFR decreases, to maintain GFR, the nephron responds by returning the GFR through dilation of the afferent arteriole. Macula densa cells detect the lower-than-normal fluid flow rate or the lower-than-normal salt composition of the filtrate. Instead of releasing adenosine, macula densa cells release a different chemical messenger called nitric oxide. Nitric oxide causes the smooth muscle cells of the afferent arteriole to relax. This causes the diameter of the afferent arteriole to increase. When the diameter of the afferent arteriole increases, more blood can enter the glomerulus, which will then increase the GFR.

How to measure GFR

we would measure creatinine in the urine since this will be easy to obtain - this is about 1mg/L in plasma, and 90mg/L in urine

the formula we use is ((creatine - urine) * urine/day)) / creatinine plasma = 180L/day = GFR

Although creatinine is a waste product that is freely filtered into Bowman's space, and it is also not reabsorbed, it isn't the perfect molecule to measure. Some creatinine is secreted into the tubule. Therefore, the amount of creatinine that is excreted is the amount filtered, plus a little extra creatinine that was secreted into the filtrate. Creatinine clearance measurements therefore slightly overestimate the GFR, sometimes by as much as 20%. Regardless, creatinine currently serves as the easiest measurement to determine a patient's GFR, albeit imperfectly.

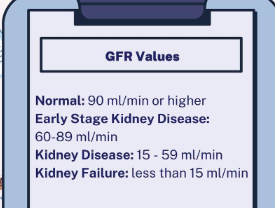

When the GFR is lower than expected

💡 Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR) and Kidney Function ✅ Normal Kidney Function:

Healthy GFR = 125 mL/min or 180 L/day

Peak kidney function occurs around age 18

Natural decline in GFR with aging is expected

📉 Decline in GFR:

Slight decreases are normal with age

Significantly low GFR = impaired kidney function

📊 GFR-Based Classification of Kidney Function:

GFR (mL/min) | Kidney Status |

|---|---|

≥ 90 | Normal (if no damage present) |

60–89 | Mild decrease |

30–59 | Moderate decrease |

15–29 | Severe decrease |

< 15 | Kidney failure |

📌 Key Point:

A GFR < 15 mL/min indicates kidney failure, and urgent medical intervention is typically required.

Stages of chronic kidney disease (CKD)

Stages of CKD

•

Stage 1-2 There is a mild decrease in GFR that can be measured, however, a patient may not be experiencing any symptoms at this time (early-stage kidney disease)

•

Stage 3 - GFR has decreased further and a patient may notice symptoms like swelling in the hands and feet, due to less blood being filtered by the damaged kidneys (kidney disease)

•

Stage 4 - This is the last stage before kidney failure, symptoms are more severe (kidney disease).

•

Stage 5 - When a kidney is in failure, this means it is no longer functioning in a way to support the body. In kidney failure, the treatment options are dialysis or a kidney transplant.

What is filtered load

how much of a substance found in the blood that can be filtered can be calculated using the measured GFR

Filtered Load = [substance]plasma * GFR

Hyponatremia, hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, hypernatremia, hyperkalemia, hypermagnesemia

hyponatremia - Lower than usual blood plasma levels of sodium (Na+)

hypokalemia - lower than usual potassium

hypomagnesemia - lower than usual magnesium

hypernatriumia - higher than normal sodium

hyperkalemia - higher than normal potassium

hypermagnesemia - higher than normal mahgnesium

Excretion Rate of Sodium: Normal range 0.5 - 2.5 %

Excretion Rate of Potassium: Normal range 6 - 9%

Excretion rate of Magnesium: Normal Range: 3-5%

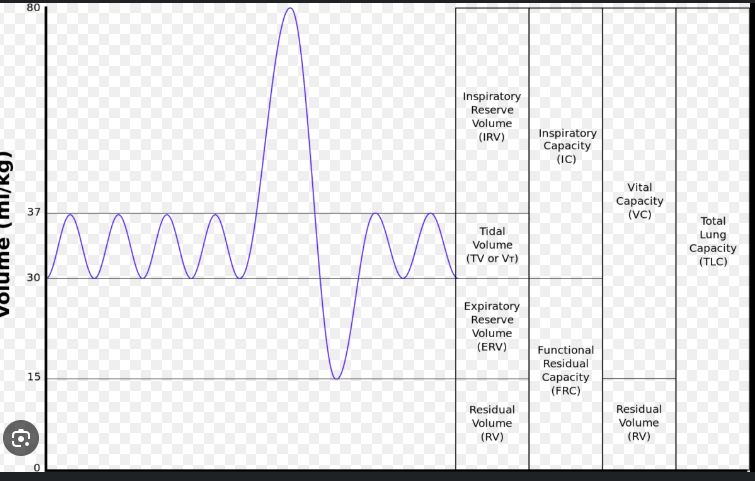

What is absorbed at each of the different stages of the tubule

proximal tubules

65% volume reabsorbed

glucose, amino acids, water, na+, k+, Cl-

Descending limb

20% volume reabsorbed (with ascending)

water, and minimal Na+

Ascending limb

Na+, K+, Cl-

Distal convoluted tubule

14% volume reabsorbed

Na+, K+, Cl-, Ca2+

Collecting duct

water, Na+

Tubule Transport

Tubule transport can either occur in between the epithelial cells, called paracellular transport or through the cells, across both the apical/luminal and basolateral membranes. Most paracellular transport is moving items from the tubule lumen, to the interstitium (and then to the blood). This is a process of reabsorption. Transcellular transport can be either a process of reabsorption or a process of secretion. Regardless, this main mechanism for how we move molecules to and from the tubule requires channels or proteins carriers to move items like glucose, ions and water, across tubule cell membranes.

tight junctions do not permit any transport between cells

Transport Mechanisms of the nephron

Channels- are small protein-lined pores that permit specific molecules through them. Movement through channels is passive, meaning no energy is required, and is driven by a concentration or electrochemical gradient, using a mechanism of diffusion.

2

Uniporters- permits the movement of a single molecule through the membrane. Unlike a channel that acts more like a tiny hole where a molecule can just pass through, uniporters are protein carriers that bind to the molecule, a mechanism offacilitated transport.

3

Symporters- these are also a type of facilitated transport. Symporters permit the movement of two or more molecules in the same direction across a membrane. Sometimes, this is also called co-transport. With this transport mechanism, at least one molecule must move down its concentration gradient to move the other molecules across the membrane. For symporters that do not use energy (ATP) directly to move molecules, the use of one molecules energy derived concentration gradient is further labelled called secondary active transport.

4

Antiporters- permits the movement of two molecules in opposite directions across a membrane. These are also called exchangers. Like symporters, one molecule must move down its concentration gradient in order for the other molecule to also move, but the movement of molecules is in opposite directions across a membrane. These are also a mechanism of facilitated transport.

5

Primary Active Transporters- requires ATP to move molecules against their concentration gradients. In the kidney, the primary active transporter that is found in every tubule cell is the Na+/K+ ATPase, moving Na+ out of the tubule cell, against a concentration gradient and K+ into the tubule cell, also against a concentration gradient. Primary active transporters can also be symporters and uriporters, although you won' t see examples of those in these renal sessions.

Regulation of Channels and Transporters

A regulated transporter means that a specific transporter or channel is changed in its function in response to a hormone. Regulation can occur at multiple levels and is specific for the type of hormone and the specific transporter or channel. Conversely, some channels/transporters are non-regulated, so transport occurs at a constant rate.

1

Regulation at the level of cellular location - Channels and transporters can only function when they are in the correct location in a cell. The location of these channels and transporters to function, is in the cell membrane. For example, water can only move through a water channel, if water channels are in the cell membrane. Water channels, like aquaporin II, can be moved out of the cell membrane, into the cytoplasm of a cell, and when that happens, the channel is no longer functional.

2

Regulation at the level of activity - Protein carriers have limited capacity to bind to specific molecules and then change shape (conformational change). Protein carriers can be stimulated to work faster to move molecules across a membrane, due to activity changes caused by hormones. The Na+/H+ exchanger, as an example, can move Na+ across a membrane, in exchange for H+. But this protein carrier, which is already present in the cell membrane, could move these ions even faster, if the cell was stimulated by a hormone. That is what is meant by regulation at the level of activity.

3

Regulation at the level of gene expression - More molecules can be moved across a membrane if there are more channels, or more protein carriers in a membrane. To make more, the cell can be stimulated to produce more copies of the instructions held within the DNA. These copies are the messenger RNAs, which are then exported out of the nucleus and then translated into the proteins. As an example, If the DNA instructions encoded for the Na+/K+ ATPase, more of these proteins, which are primary active transporters, would be present in the cell membrane and could transport more Na+ and K+ ions across the cell membrane.

Urine Volume Ranges

The average person will expel 1.5 litres of urine per day. However, depending on the situation, this value can be as low as 0.4 litres/day or as high as 25 litres/day. Even if an individual is very dehydrated, some urine will need to be produced daily since our bodies still have to excrete excess solutes and waste products. This minimal urine production is called "obligatory urine loss".

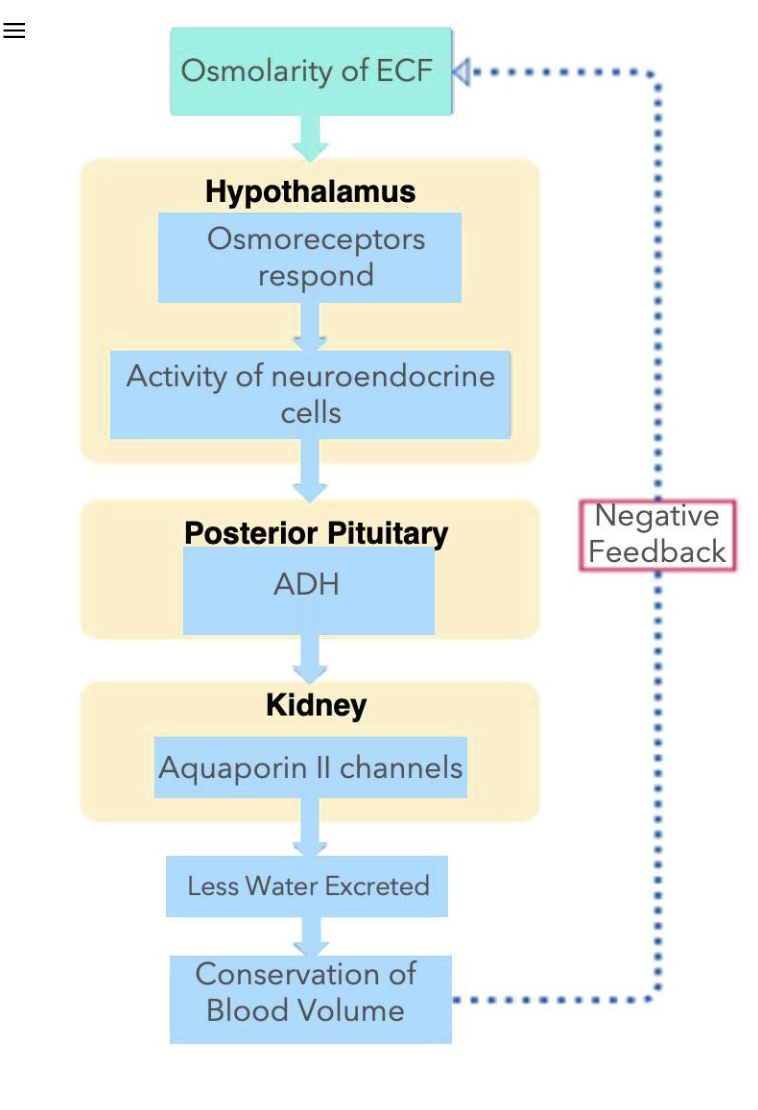

Antidiuretic Hormone

Antidiuretic Hormone

Changes to how much water is reabsorbed by nephrons is due to how much of the hormone, antidiuretic hormone (ADH) is in the blood. Diuretic comes from the word diuresis, meaning to produce more urine. Therefore, as the name of the hormone implies, ADH causes anti-diuresis, or results in less urine being produced. When there is more ADH circulating in the blood stream, the reason why less urine is being produced by the kidneys, is because much more water is being reabsorbed by the nephrons, due to the signalling by ADH. ADH also has roles in affecting the diameter of blood vessels, therefore, sometimes this same hormone is called Vasopressin.

There are neurons that don't release neurotransmitters, but instead they release hormones. These neurons are also called neuroendocrine cells. There are a subset of neuroendocrine cells that produce ADH. The cell bodies of these neurons are located in the region of the brain called the hypothalamus. The axons from these neurons project into and form the part of the pituitary gland, called the posterior pituitary. You will learn much more about the anterior and posterior pituitary glands from the Endocrine Section of this course, but for now, here is a quick overview of these structures.

Baroreceptors and osmoreceptors

Baroreceptors - These sensory receptors are located in the aortic arch and in the carotid sinus. At a "normal" blood pressure, these receptors are sending action potentials to the brain; specifically the cardiovascular centre found within the medulla oblongata. When blood pressure decreases, then less action potentials are sent to the brain, and conversely, when blood pressure increases, more action potentials are sent to the brain.

2

Osmoreceptors - These sensory receptors are located in the brain, within the hypothalamus and also nearby the hypothalamus. The osmoreceptors send more action potentials to the other neurons they are connected to when plasma osmolarity is increased. Conversely, when plasma osmolarity is decreased, they send less action potentials.

Baroreceptors

Recall from the cardiovascular section of this course, that you have learned about baroreceptors. In addition to how baroreceptors work in the baroreceptor reflex to change heart rate and blood vessel diameter, these mechanical sensors also connect to the hypothalamus to stimulate the release of ADH from the posterior pituitary. When blood pressure is lower than normal, this results in ADH release from these neurons, into the blood.

Osmoreceptors

ADH is triggered for release also when plasma osmolarity is higher than normal. Osmoreceptors near and in the hypothalamus region of the brain can detect these osmolarity changes. Osmoreceptors are sensory neurons that will change in volume, resulting in the generation of action potentials. If the cell body of the osmoreceptor reduces in volume, also called shrinking or shrivelling, action potentials occur within the neuron and excitatory neurotransmitters are released. Osmoreceptors synapse on the neuroendocrine cells that make ADH, causing release of ADH from the posterior pituitary.

Low Plasma Osmolarity

When the plasma osmolarity is lower than normal, water moves into the osmoreceptor and causes the cell body to swell. No action potentials are generated in the osmoreceptor when low plasma osmolarity is detected.

Neuroendocrine Cell Not Activated

No excitatory neurotransmitter is released onto the neuroendocrine cell and therefore no action potential is generated.

Axon Terminal

Although ADH is stored within the axon terminals found within the posterior pituitary, the hormone is not released since there is no action potential.

No ADH released

Low plasma osmolarity results in no ADH being released into the blood.

High Plasma Osmolarity

When the plasma osmolarity is higher than normal, water moves out of the osmoreceptor and causes the cell body to shrivel. Action potentials are generated in the osmoreceptor.

ADH at the Collecting Duct

💧 ADH and Water Reabsorption in the Collecting Duct 🔄 What is ADH?

Antidiuretic Hormone (ADH) circulates in the blood and binds to receptors on specific cells.

These receptors are located on the plasma membrane of principal cells in the collecting duct of the nephron.

📬 What Happens When ADH Binds?

ADH binds to its receptor on the principal cell membrane.

This activates intracellular signaling (mechanism not required to know).

The outcome:

Aquaporin II (AQP2) channels, which are stored inside the cell in vesicles, are moved to the luminal/apical membrane.

Insertion of AQP2 channels into the luminal membrane allows water to be reabsorbed from the filtrate into the cell.

✅ More AQP2 at the membrane = more water reabsorption

🚫 What Happens Without ADH?

No ADH = No stimulation of principal cells.

AQP2 channels are removed from the luminal membrane via endocytosis.

Channels are stored in vesicles, where they cannot transport water.

The luminal membrane becomes impermeable to water → No water reabsorption.

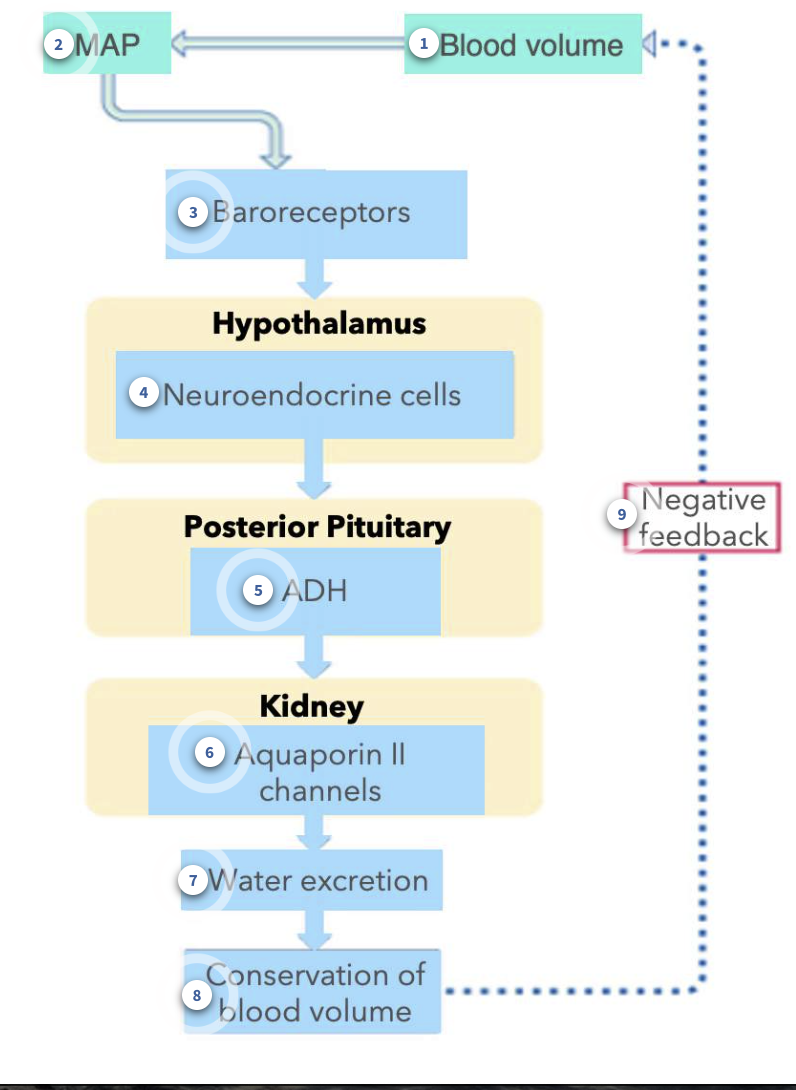

Baroreceptors & ADH Release

Blood volume changes

The volume of the blood can decrease, as in scenarios of not having drank enough water (dehydration). When not enough water is remaining in the body, this directly impacts and reduces the volume of blood.

Mean arterial pressure

a decrease in the blood volume will decrease the MAP

Detection by baroreceptors

a change in the pressure is detectable by baroreceptors. A decrease in pressure reults in less APs being sent to the cardiovascular centre in the medulla oblangata

Neuroendocrine cells

Within the hypothalamus, are a subset of neurons that make the hormone, ADH. When blood pressure is lower than normal, this will stimulate these neuroendocrine cells, causing an increase in action potentials within these specialized neurons.

Antidiuretic hormone

When the neuroendocrine cells from the hypothalamus are stimulated, the action potentials travel down the axons, which are located within the posterior pituitary. ADH is released from the axon terminals of these neurons.

Principal cells

In the collecting duct, principal cells have receptors for ADH. Binding of ADH to its receptor on the plasma membrane of the cells causes more aquaporin II channels to insert into the luminal membrane. More water is reabsorbed from the filtrate.

Urine Volume

When more water is reabsorbed from the filtrate in the tubule lumen of nephrons, less water is excreted from the kidneys. That means that there is a reduced urine volume.

Blood Volume Changes

As more and more water is being reabsorbed from the filtrate (instead of being excreted in the urine), blood volume can be conserved.

Negative Feedback

When blood volume is returned to normal, then baroreceptors no longer cause a release of ADH from the posterior pituitary.

Osmoreceptors & ADH Release

Similarly, activation of osmoreceptors can also cause the release of ADH from the posterior pituitary.

When there is less water in the body, this will cause an increase in the osmolarity of the extracellular fluid (ECF), which includes the blood. Osmoreceptors can detect changes in osmolarity.

Recall that osmoreceptors respond by physically changing the volume of the cell body of these sensory neurons. A shrivelling or decrease in osmoreceptor volume, will trigger action potentials.

Osmoreceptors release excitatory neurotransmitters on the neuroendocrine cells in the hypothalamus. Once activated, this causes the release of ADH from the posterior pituitary. Just like in the baroreceptor example, ADH in the blood will result in an increase in the number of aquaporin II channels in the luminal membrane of principal cells of the collecting duct. Less water is excreted in urine, and blood volume is conserved.

Behaviour Responses to Correct Disruptions in Water Balance

Behavioural Responses to Correct Disruptions in Water Balance

Although increased reabsorption of water by the kidneys is an important response, it is usually not adequate to return the blood volume to homeostatic levels. When water levels are too low in the body, a necessary response is to consume more water.

Thirst is the urge to consume fluids, and usually results in the behaviour to drink fluids. The same osmoreceptors that sense plasma osmolarity and trigger ADH release, can also trigger another region of the brain, to cause the sensation of thirst.

Once adequate levels of fluid are consumed, along with the conservation of water by the kidneys, total body water and blood volume can be returned to normal. Once corrected, the sensation of thirst ceases, along with decreasing the release of ADH.

The ability of water to move out of the filtrate, across principal cells, into the interstitial space and then into the nearby blood vessels requires two things:

Aquaporin channels in both the luminal and basolateral membranes of epithelial cells.

A gradient of solutes allows for water to move by osmosis.

The presence of water channels in the collecting duct is dependent on ADH. The action of ADH is to insert water channels, specifically aquaporin II channels, in the luminal membrane. When both the luminal and basolateral membranes have water channels, water can move across the principal cell membranes.

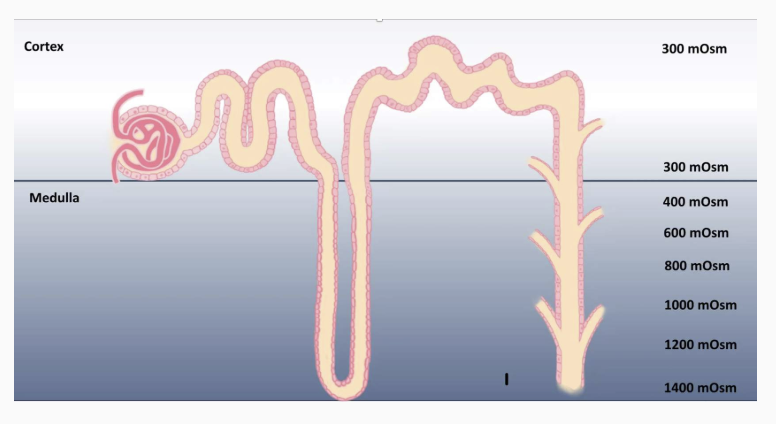

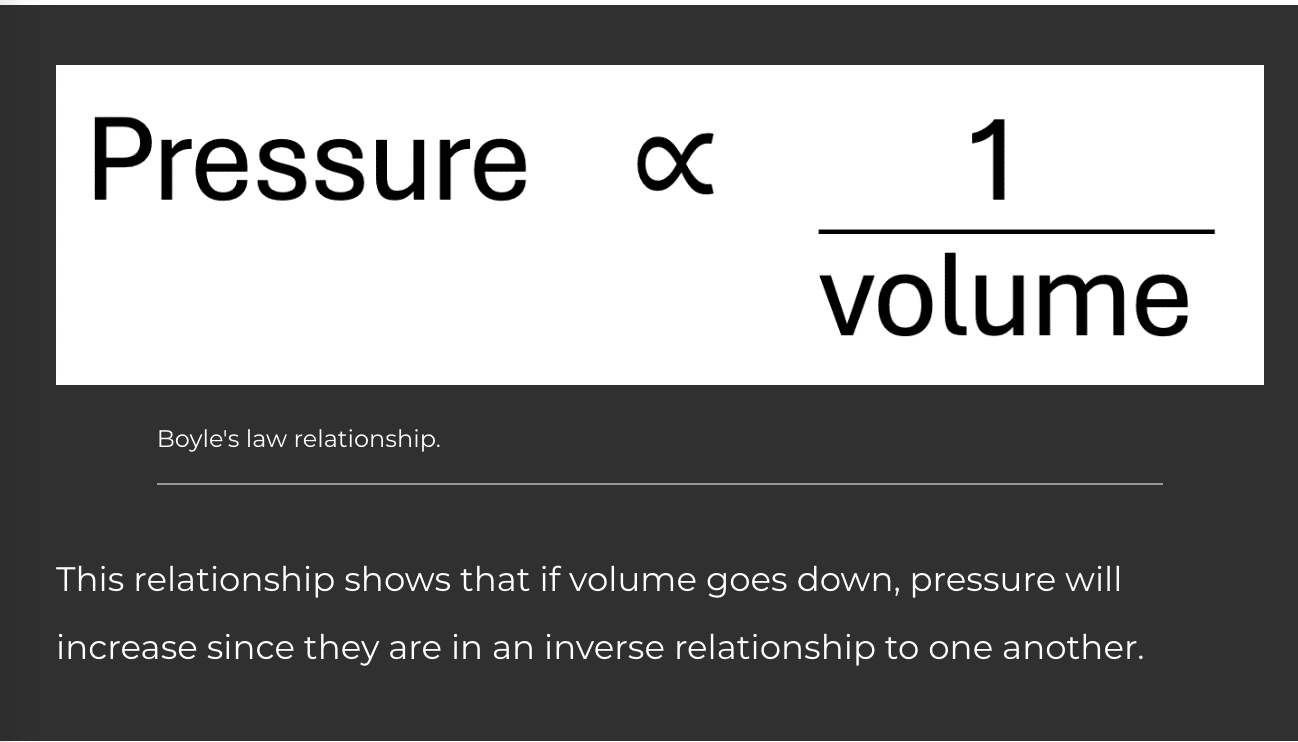

For osmosis to occur, without removing solutes from the filtrate at the same time, the outside interstitium needs to be more concentrated. Recall, that water moves by osmosis from an area of higher water concentration to lower water concentration. Another way to state this is that water will move by osmosis from an area of lower solute to an area of higher solute. The medulla region of the kidney is unique because the concentration of the interstitium becomes more and more concentrated. While most tissues in the body have an interstitial concentration of approximately 300 mOsm, the lowest region of the medulla can be as concentrated as 1400 mOsm. With more solutes in the interstitium, water will be driven to move by osmosis out of the lumen of the nephron tubules, through water channels.

Urine Osmolarity & Volume Changes

In humans, the most concentrated urine can be is 1400 mOsm, while the most dilute urine humans can produce is approximately 100 mOsm. As the filtrate passes through the collecting duct, if there are many aquaporin II channels in the luminal membrane, water moving out by osmosis across the basolateral membrane can be followed by water from the filtrate, through the luminal membrane. Since the medulla of the kidney is as concentrated as 1400 mOsm, water moves by osmosis until the filtrate in the lumen and the interstitial space are equal in osmolarity. If it were possible for the renal medulla to increase interstitial osmolarity, this capability could be enhanced. The filtrate leaving the distal convoluted tubule is around 100 mOsm after having passed through the other tubule segments. If no aquaporin II channels are inserted in the luminal membrane of principal cells, the filtrate would descend through the collecting duct without without being reabsorbed, producing a high volume, low osmolarity urine.

Examples of Diuretics

1

Alcohol compounds, such as ethanol, are known diuretics. Ingestion of alcohol results in a larger than normal urine production and can lead to dehydration if body water isn’t replaced. Alcohol does this through the inhibition of release of ADH from the posterior pituitary, despite signals from the body that may try to trigger ADH release.

2

Caffeine being a diuretic is actually a myth. Although this may be surprising, it is not considered a true diuretic, although it may feel that more urine is being produced than normal, as in the case of alcohol ingestion. Caffeine does not change ADH release or the function of the ADH receptor. Instead, caffeine, in moderate doses, results in increased contractility of smooth muscle. The bladder, is therefore affected with caffeine ingestion, leading to a greater urgency to urinate, but this does not affect that total water balance but produces the sensation that one is producing more urine than usual.

3

Diabetes Insipidus is a rare disease that is not related to diabetes mellitus. Although both result in an increase in urine production, diabetes insipidus produces large volumes of urine because the nephron tubules do not reabsorb enough water.

Diuresis - this increases the amount of urine that is being produced, usually causes an imbalance

Diabetes Insipidus

Individuals that have this rare disease can have one of two forms, both that result in exceptionally large volumes of urine, sometimes as large as 25 litres per day.

1

Neurogenic (central) Diabetes Insipidus- caused by damage, such as head trauma or surgery, to either the hypothalamus or the posterior pituitary. In either case, ADH is not released normally, either not at all, or in smaller amounts. The issues with either brain region can also be a result of rare genetic conditions where ADH is not produced, or not released properly.

2

Nephrogenic Diabetes Insipidus - rare genetic mutations can also cause nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, where the receptors for ADH cannot respond to the hormone when it is in the blood.

Ingesting more water is necessary for both types of diabetes insipidus, but promising options for central diabetes insipidus include a nasal spray that contains a drug that looks very much like the hormone ADH. The body can respond to this synthetic ADH so that if you don't make any of your own, you can supply it into the blood stream, through the nasal cavity.

There are two hormone systems that regulate sodium levels. One hormone pathway for when sodium levels are low, and a different hormone is released when sodium levels are high.

Total Body Sodium Levels

Sodium (Na+) intake levels can vary drastically from person to person and from day to day. A person may ingest as little as 0.05 grams of Na+ per day or as much as 25 grams of Na+ per day. The kidney is responsible for maintaining Na+ balance and can alter excretion to maintain homeostasis.

1

When Na+ levels are lower than normal, the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) is activated, releasing two hormones, angiotensin II and aldosterone.

2

Conversely, when Na+ levels are too high, the RAAS pathway is decreased and instead a different hormone is released called atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), also known as atrial natriuretic factor (ANF).

Sodium Levels and the Connection to Blood Pressure

🔗 Why Sodium (Na⁺) Matters:

Sodium is a major ion in the extracellular fluid (ECF).

Changes in sodium levels affect ECF volume, which includes blood plasma.

🔼 When Sodium is High:

ECF volume expands.

Blood plasma volume increases → blood volume increases.

Result: Blood pressure increases.

🔽 When Sodium is Low:

ECF volume shrinks.

Blood plasma and total blood volume decrease.

Result: Blood pressure decreases.

🧠 How the Body Responds:

The body detects changes in:

Blood pressure

Filtrate composition (in kidneys)

It then regulates sodium levels through hormone release (e.g., RAAS pathway), because:

Sodium concentration, ECF volume, and blood pressure are tightly linked.

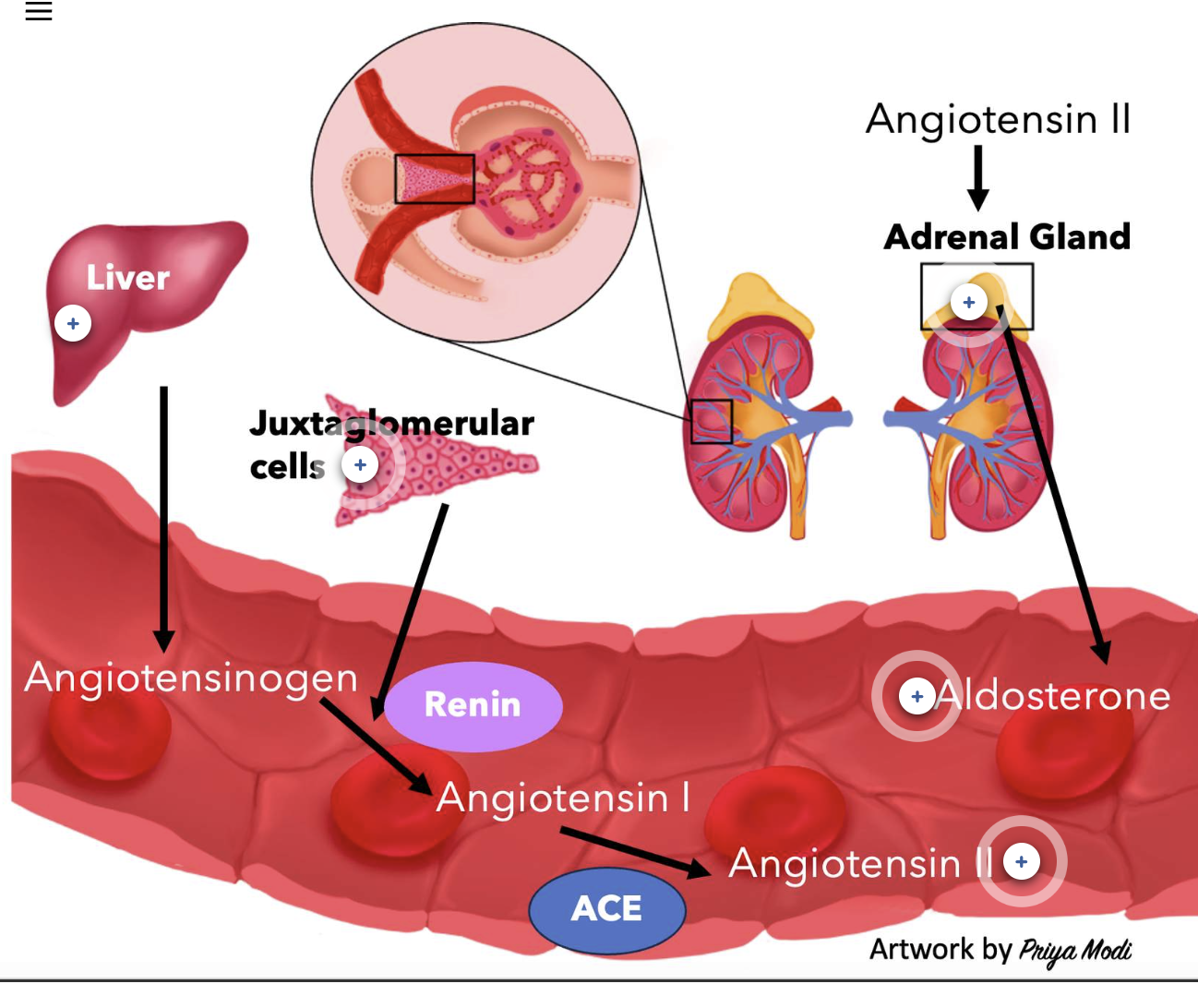

Steps of the RAAS Pathway

The Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS) Pathway:

The RAAS pathway is a multi-step system that helps regulate blood pressure and fluid balance. It leads to the production of one enzyme (renin) and two hormones (angiotensin II and aldosterone).

Renin Production

Renin is an enzyme made by the juxtaglomerular (JG) cells of the afferent arteriole in the kidney. These cells release renin in response to low sodium (Na⁺) levels.Angiotensinogen Activation

Renin enters the bloodstream and acts on angiotensinogen, a non-active protein made and continuously released by the liver. Angiotensinogen is a 452-amino acid peptide.Formation of Angiotensin I

Renin cleaves angiotensinogen to form angiotensin I, which is also inactive and consists of 10 amino acids.Conversion to Angiotensin II

Angiotensin I is then converted into the active hormone angiotensin II by the enzyme angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE).

ACE is present throughout the circulation, but it is found in the highest amounts in the capillary endothelial cells of the lungs.

This cleavage turns angiotensin I (10 amino acids) into angiotensin II (8 amino acids).Angiotensin II Actions

Angiotensin II is the active hormone that helps raise blood pressure and stimulate aldosterone release, which promotes sodium and water retention.

Control of Renin Release

Angiotensin II is produced in the blood through a series of cleavage events, limited by the presence of renin secretion into the blood. In the absence of renin, angiotensin I is never produced and therefore angiotensin II cannot be formed in the blood. Careful regulation of renin release will therefore determine if angiotensin II is produced in the blood. Renin is stimulated for release in response to decreased levels of Na+ in the blood. Sensory receptors called chemoreceptors can detect this decreased concentration of Na+. Additionally, renin is released in response to decreased blood pressure, detected by baroreceptors.

1

Chemoreceptors - As the filtrate travels through the tubule, the composition of the filtrate can be detected by the macula densa cells, which behave as chemoreceptors.

2

Baroreceptors - Located in the aortic arch and in the carotid sinus, these sensory receptors don't just connect to the cardiovascular centre in the medulla oblongata, but also connect to neurons which directly innervate the juxtaglomerular cells in the kidneys.

Function of the Juxtaglomerular Apparatus (JGA)

When Na+ levels are lower in the blood, the concentration of Na+ will also be lower in the filtrate that is produced in nephrons. The macula densa cells, which are found within the juxtaglomerular apparatus, can detect this decrease in Na+ levels in the filtrate. Lower than normal Na+ levels will cause the macula densa cells to secrete a chemical messenger (paracrine factor) that causes the nearby juxtaglomerular cells to secrete the enzyme renin in the blood.

Juxtaglomerular cells are also triggered to secrete renin when blood pressure has decreased in the body. Baroreceptors stimulate neurons which synapse on juxtaglomerular cells, signalling to cause a the secretion of renin in the blood.

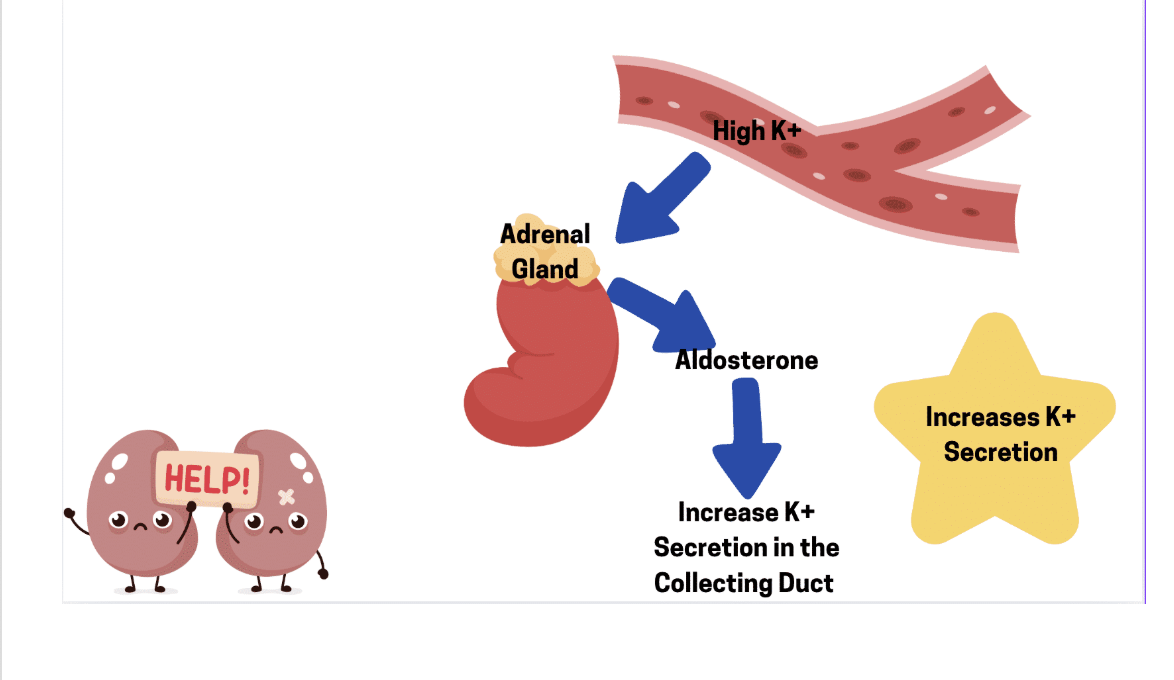

Control of Aldosterone Release

The hormone aldosterone is released into the blood as part of the RAAS pathway. Aldosterone is a steroid hormone produced and released by the adrenal gland, an endocrine tissue that is positioned on top of each kidney. One of the stimuli to release aldosterone is angiotensin II. When angiotensin II is produced in the blood, it will activate a set of cells within the adrenal gland to release the hormone aldosterone into the blood. Aldosterone is not only released into the blood because of angiotensin II, there are other signals that can cause the release of aldosterone into the blood, including higher than normal concentrations of the ion potassium (K+).

liver - Angiotensinogen is a large protein that is made by and released from the liver. This constant/steady release is also called constitutive production.

juxtaglomerular cells - Juxtaglomerular cells are also called granular cells. These cells secrete the enzyme renin into the blood WHEN the levels of sodium are lower than usual.

Angiotensin II - Angiotensin II is a peptide hormone that is made from the sequential activity of enzymes, that turn the protein angiotensinogen into angiotensin I and then to angiotensin II.

Aldosterone - Aldosterone is a steroid hormone that is produced by the adrenal glands. Angiotensin II is one stimulus that will cause the adrenal glands to secrete aldosterone into the blood.

Adrenal Gland - The adrenal glands are an endocrine tissue the produce and release a number of different hormones, including aldosterone.

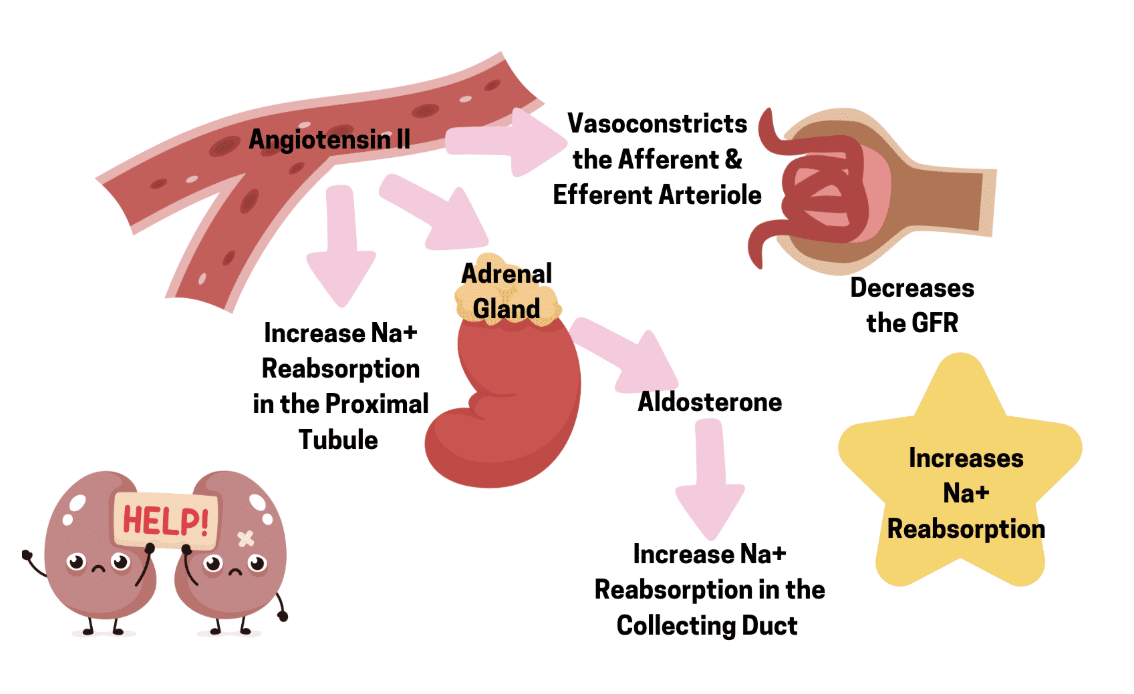

Actions of Angiotensin II

Once in the blood stream, the peptide hormone angiotensin II will result in responses on cells that express the angiotensin II receptor. Proximal tubule epithelial cells express one of these angiotensin II receptors that if bound by the hormone, results in a signaling cascade, causing the proximal tubule cells to change how it functions.

1

Na+/H+ exchanger - The activity of the exchanger on the luminal membrane is increased. More Na+ moves into the tubule cells from the filtrate, and more H+ is secreted from the tubule cells into the filtrate. We will focus on the Na+ movement in this session. There is an important outcome for H+ secretion, but that will be discussed in our acid/base lesson.

2

Na+/K+ ATPase - The increased activity of the primary active transporter on the basolateral membrane results in more Na+ being exported out of the proximal tubule cell and into the surrounding interstitial fluid, which is then reabsorbed in the blood vessels nearby.