Topic 7 - Oral Cavity and GI Tract

1/99

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

100 Terms

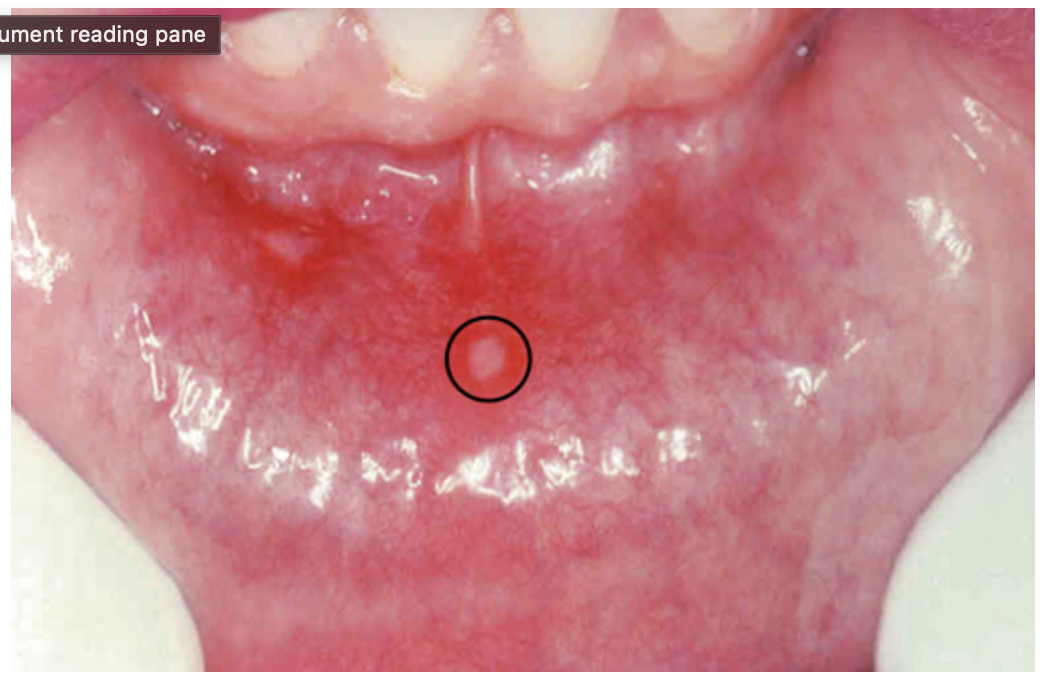

Aphthous ulcer. Single ulceration with an erythematous halo surrounding a grayish fibrinopurulent membrane (circle).

Stromal proliferations. (A) Fibroma, appearing as a pink exophytic nodule on the buccal mucosa.

Stromal proliferations. (B) Pyogenic granuloma, seen as an erythematous hemorrhagic exophytic mass arising from the gingival mucosa.

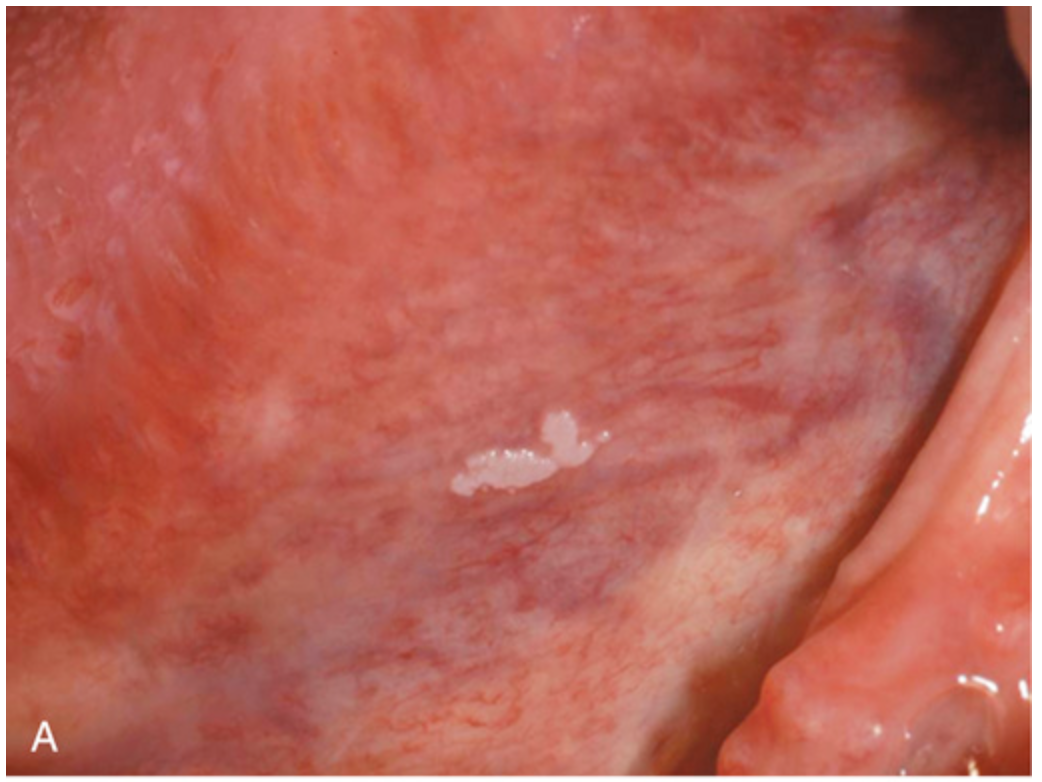

Leukoplakia. (A) Gross appearance of leukoplakia is highly variable. In this example, the lesion is smooth with well-demarcated borders and minimal elevation.

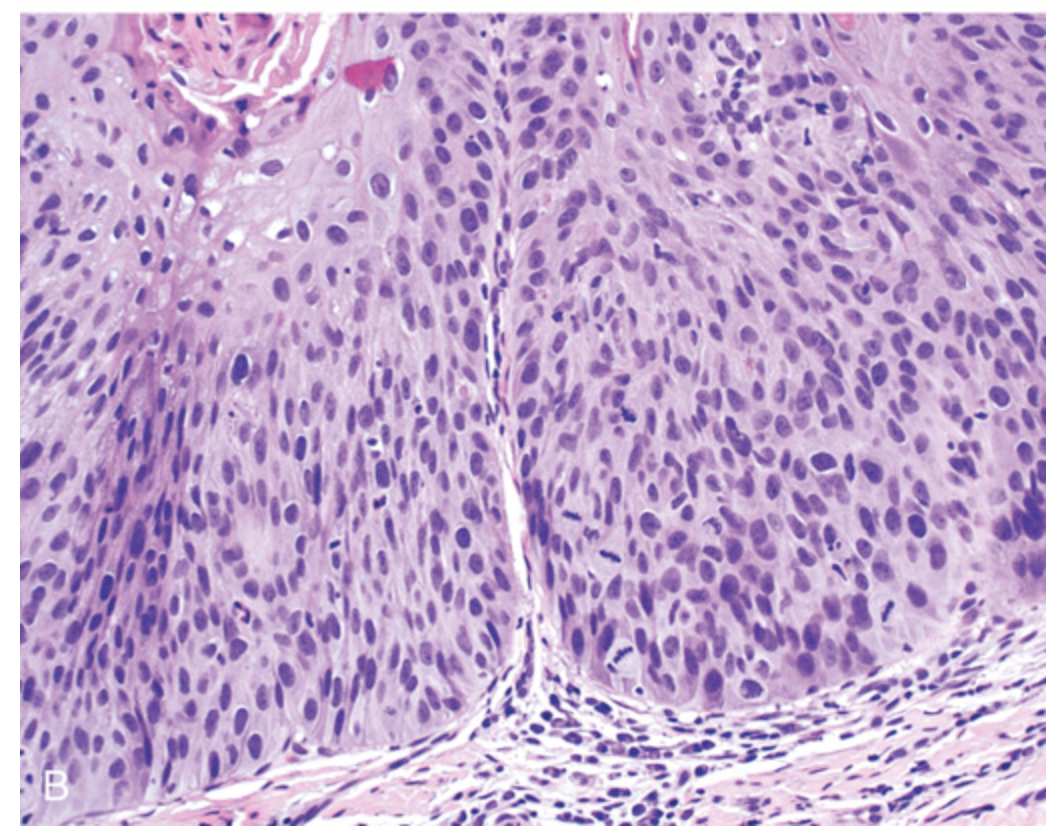

Leukoplakia. (B) Histologic appearance of leukoplakia showing dysplasia, characterized by nuclear and cellular pleomorphism and loss of normal maturation.

Oral squamous cell carcinoma. (A) Gross appearance demonstrating ulceration and induration of the oral mucosa.

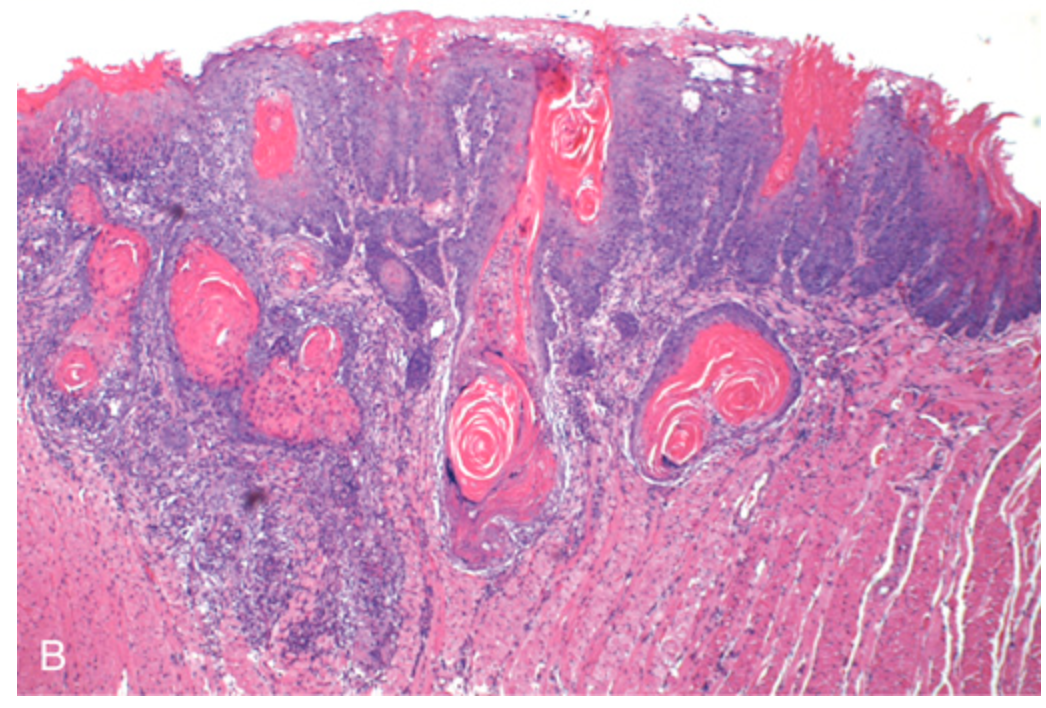

Oral squamous cell carcinoma. (B) Histologic appearance showing numerous nests and islands of malignant keratinocytes invading the underlying connective tissue stroma.

Mucocele. (A) Fluctuant fluid-filled lesion on the lower lip after trauma.

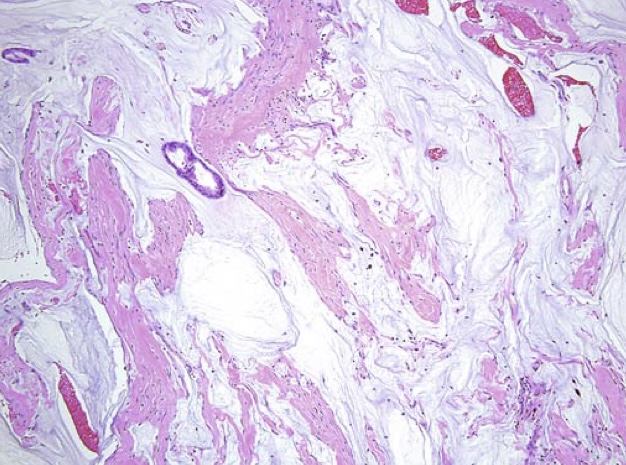

Mucocele. (B) Cystlike cavity (right) filled with mucinous material and lined by organizing granulation tissue. The normal gland acini are seen on the left.

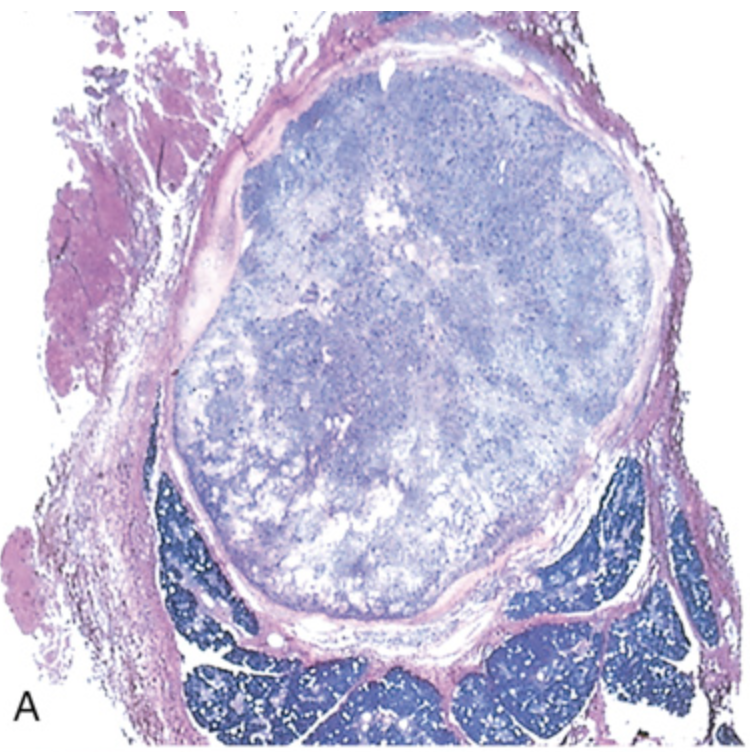

Pleomorphic adenoma. (A) Low-power view showing a well-demarcated tumor with adjacent, deeply staining, normal salivary gland parenchyma.

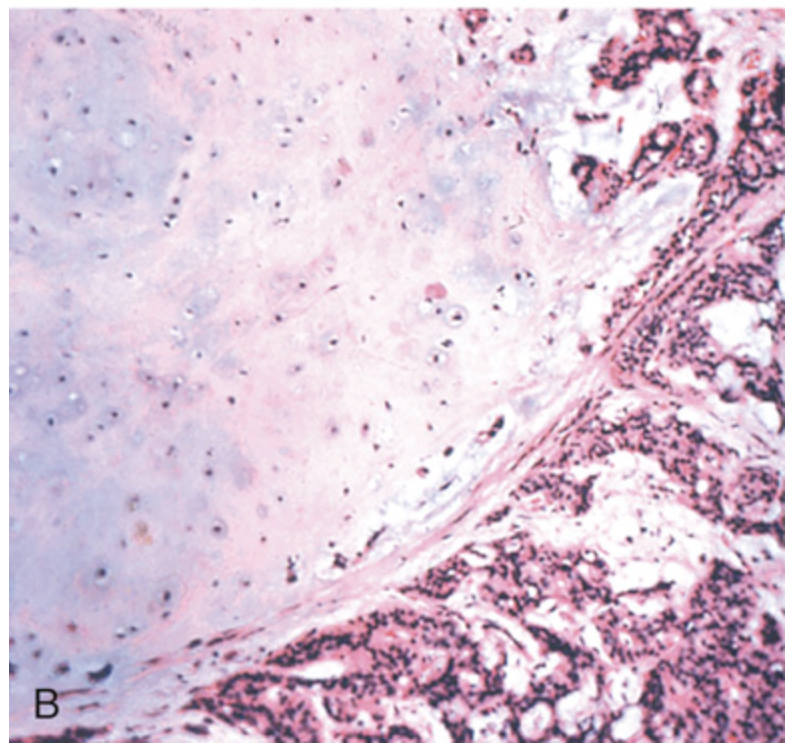

Pleomorphic adenoma. (B) High-power view showing epithelial cells as well as myoepithelial cells within chondroid matrix material.

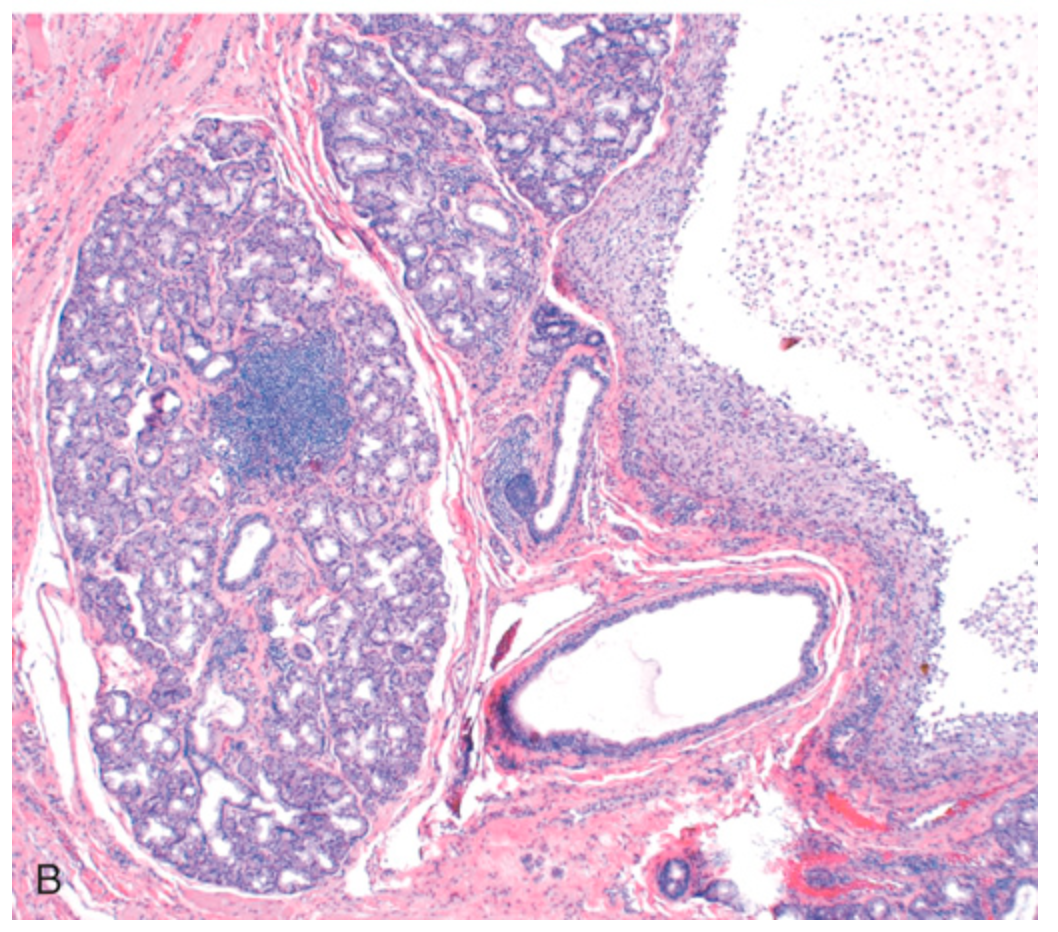

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma. (A) Low-power view showing the tumor growing in islands with cystic spaces.

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma. (B) High-power view showing that the cystic space is lined by a mixture of cells producing mucin and epidermoid cells.

Ameloblastoma. Cyst formation in ameloblastoma. The columnar epithelium underlies areas of squamous differentiation and overlies a sparsely cellular stroma containing stellate cells.

Esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula. (A) Blind upper and lower esophagus connected by a thin strand of connective tissue. (B) Blind upper segment and fistula between the lower segment and the trachea. (C) Fistula without atresia between the esophagus and the trachea. The lesion shown in (B) is the most common of these varied abnormalities.

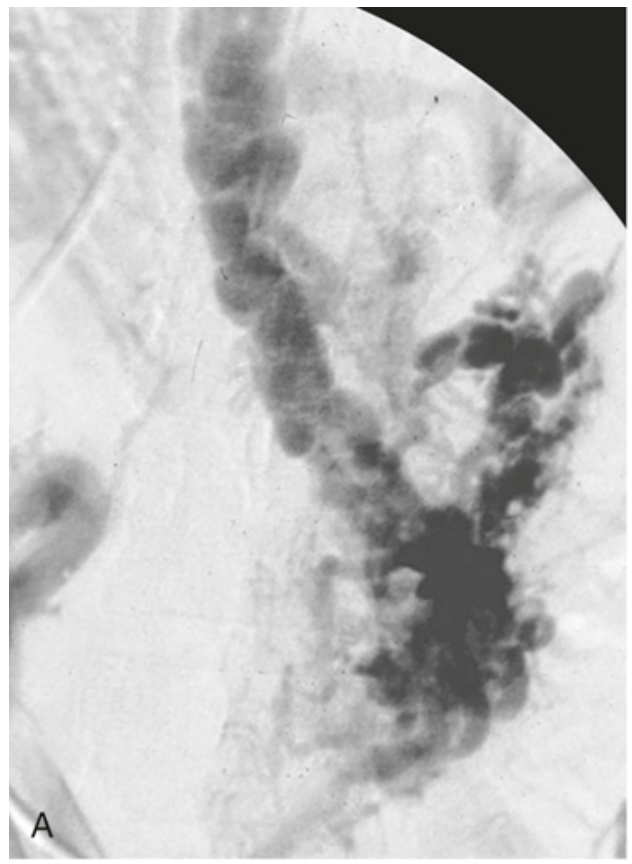

Esophageal varices. (A) Angiogram showing several tortuous esophageal varices.

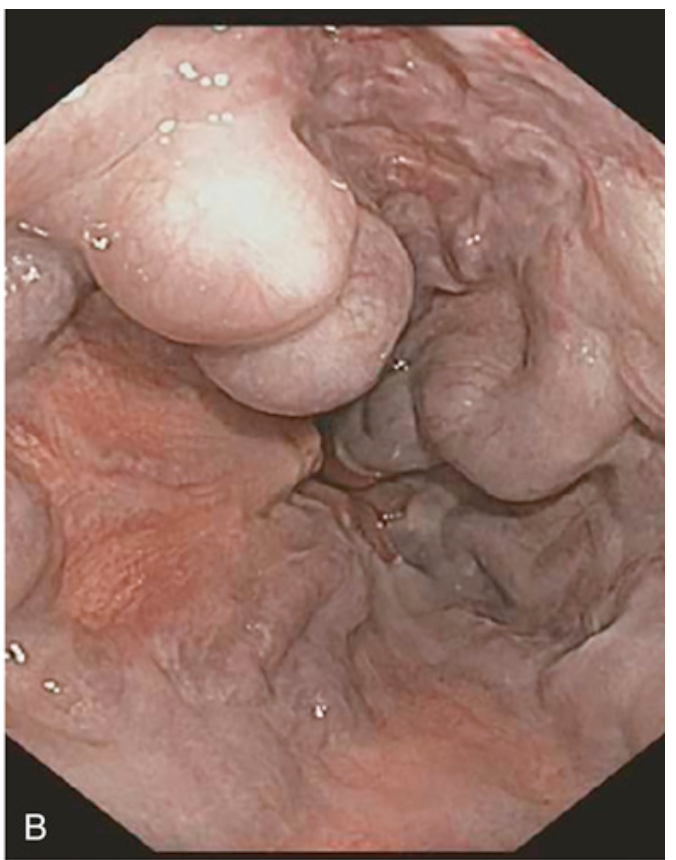

Esophageal varices. (B) Endoscopic view of esophageal varices, readily visible as bulging submucosal vessels.

Esophageal varices. (C) Collapsed varices are present in this postmortem specimen corresponding to the angiogram in (A). The polypoid areas are sites of variceal hemorrhage that were ligated with bands.

Esophageal varices. (D) Dilated varices beneath intact squamous mucosa.

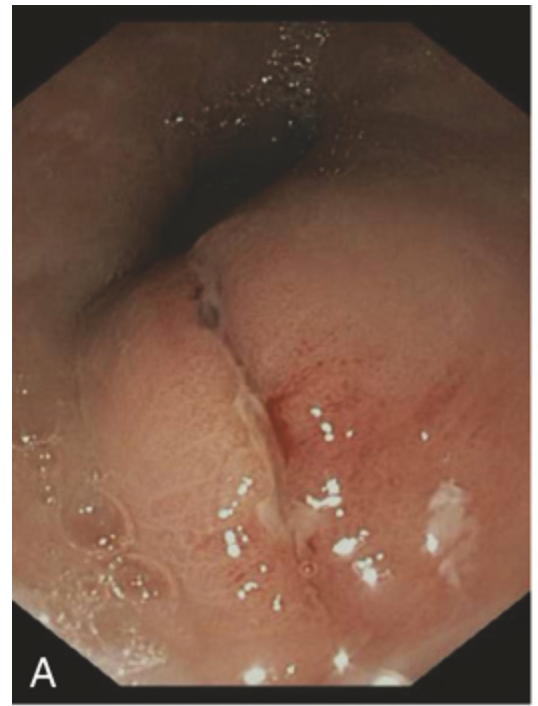

Traumatic and viral esophagitis. (A) Endoscopic view of a longitudinally oriented Mallory-Weiss tear. These superficial lacerations can range from millimeters to several centimeters in length.

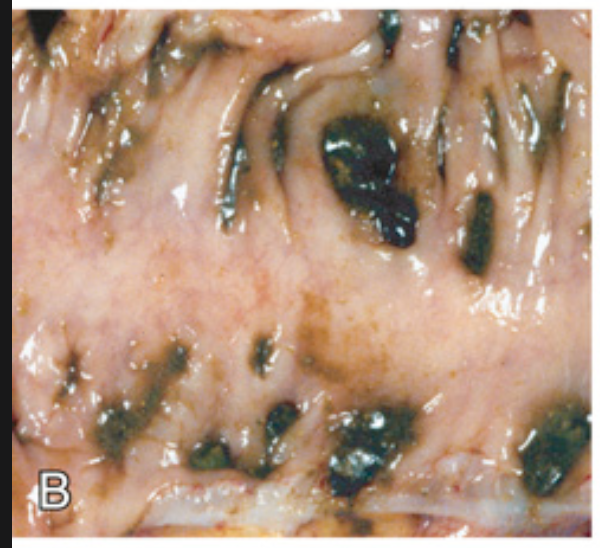

Traumatic and viral esophagitis. (B) Postmortem specimen with multiple herpetic ulcers in the distal esophagus.

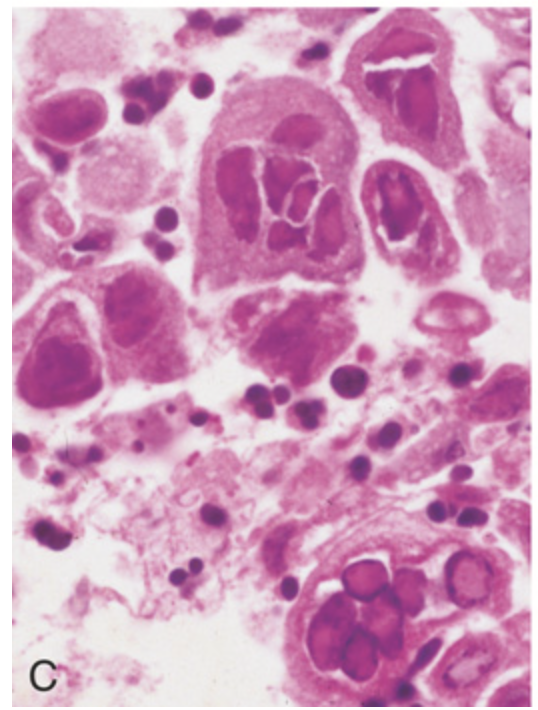

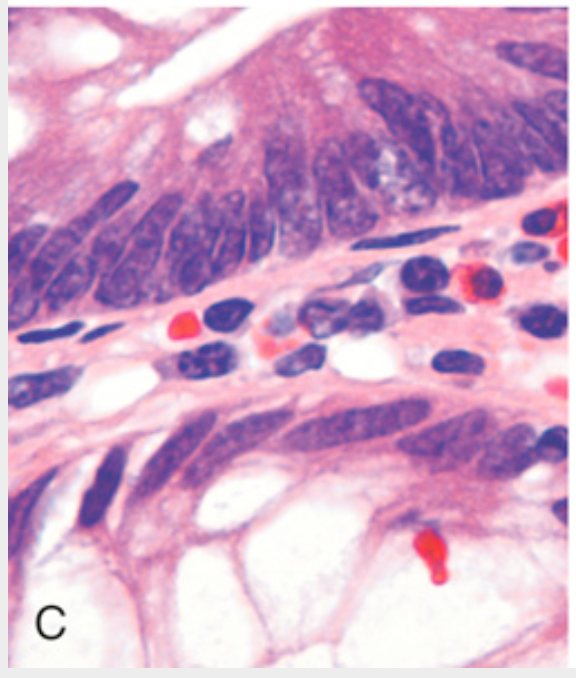

Traumatic and viral esophagitis. (C) Multinucleate squamous cells containing herpesvirus nuclear inclusions.

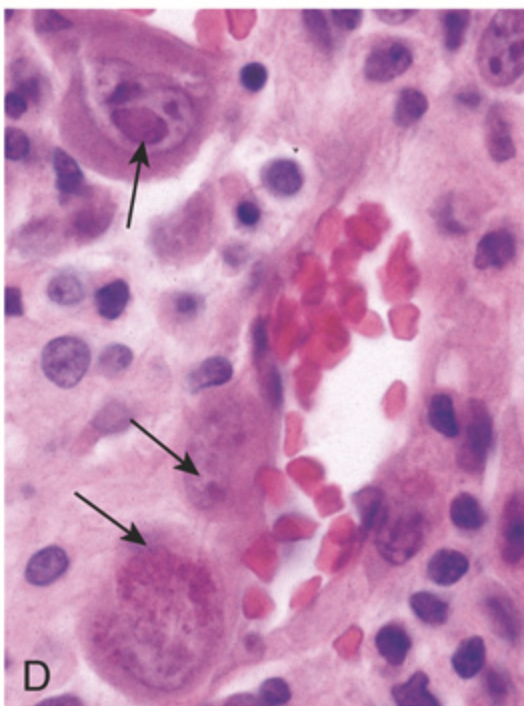

Traumatic and viral esophagitis. (D) Cytomegalovirus-infected endothelial cells with nuclear and cytoplasmic inclusions (arrows).

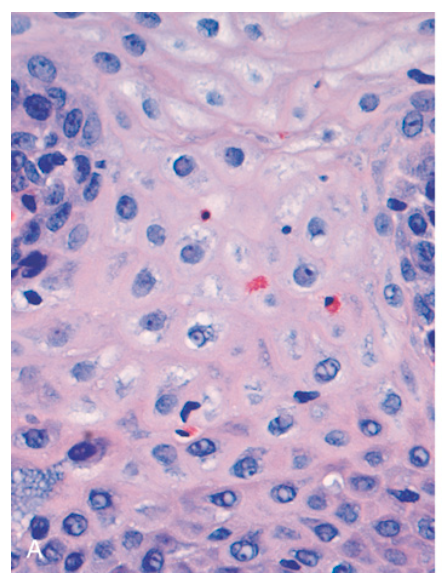

Esophagitis. (A) Reflux esophagitis with scattered intraepithelial eosinophils.

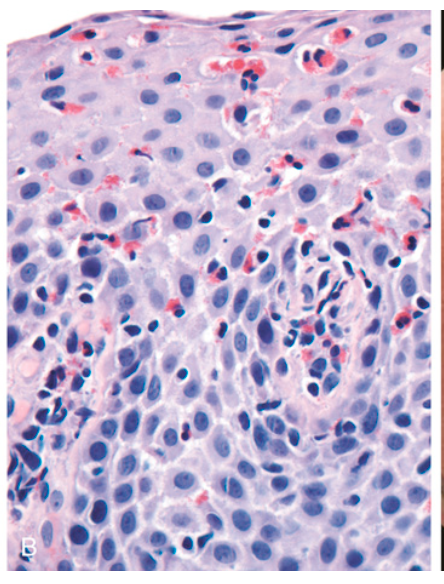

Esophagitis. (B) Eosinophilic esophagitis with numerous intraepithelial eosinophils and scattered eosinophilic microabscesses.

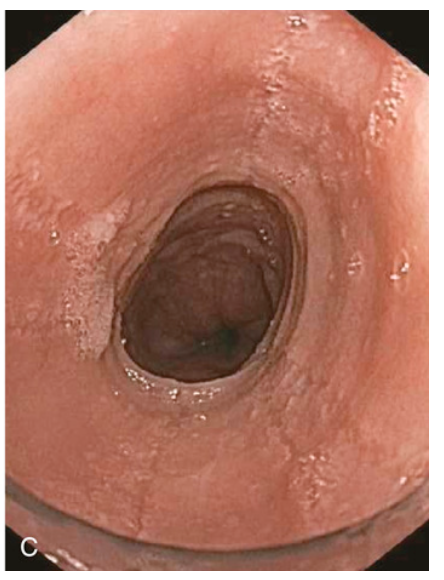

Esophagitis. (C) Endoscopy reveals circumferential rings in the proximal esophagus of this patient with eosinophilic esophagitis.

Barrett esophagus. (A) Barrett esophagus at endoscopy, seen as a patch of reddish mucosa.

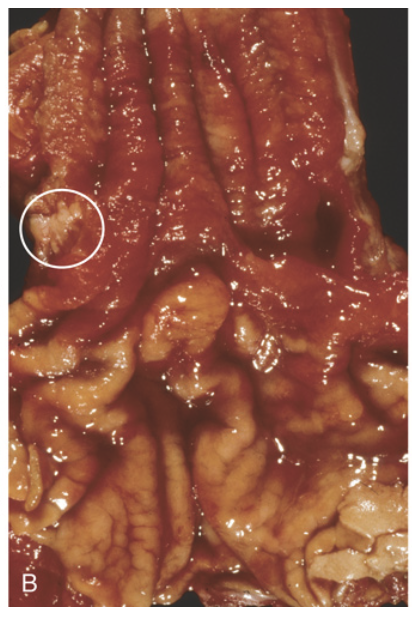

Barrett esophagus. (B) Gross image of Barrett esophagus (compare to Fig. 13.7C). Only a focal area of paler squamous mucosa (circle) remains within the predominantly metaplastic, reddish mucosa of the distal esophagus.

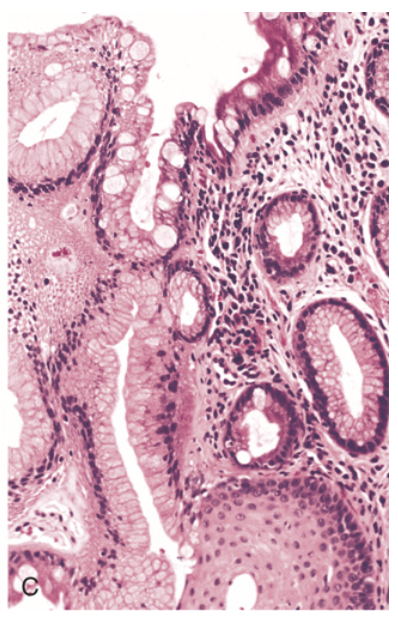

Barrett esophagus. (C) Histologic appearance of the gastroesophageal junction in Barrett esophagus. Note the transition between esophageal squamous mucosa (lower right) and metaplastic mucosa containing goblet cells (upper).

Esophageal adenocarcinoma. (A) Adenocarcinoma usually occurs distally and, as in this case, often involves the gastric cardia.

Esophageal adenocarcinoma. (B) Esophageal adenocarcinoma growing as back-to-back glands containing blue-gray mucin.

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. (A) Squamous cell carcinoma most frequently is found in the mid esophagus, where it commonly causes strictures.

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. (B) Squamous cell carcinoma composed of nests of malignant cells that partially recapitulate the stratified organization of squamous epithelium.

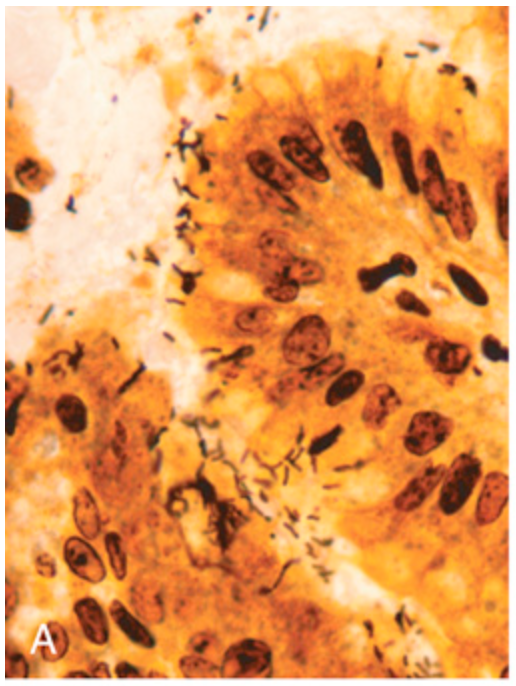

H. pylori gastritis. (A) Spiral-shaped H. pylori bacilli are highlighted in this Warthin-Starry silver stain. Organisms are abundant within surface mucus.

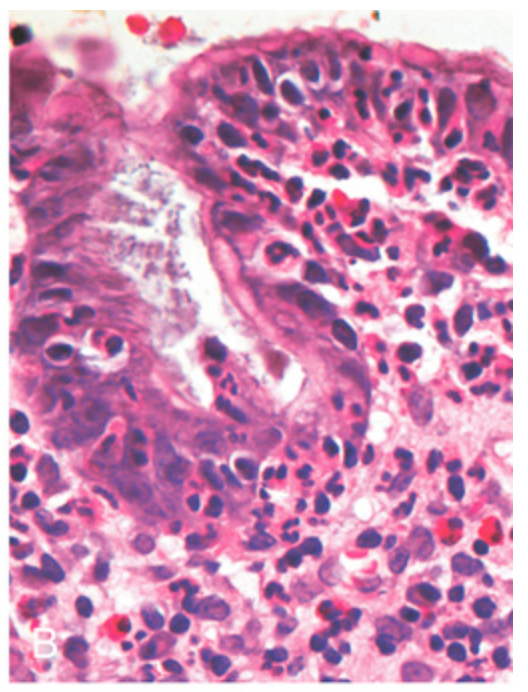

H. pylori gastritis. (B) Intraepithelial and lamina propria neutrophils are prominent.

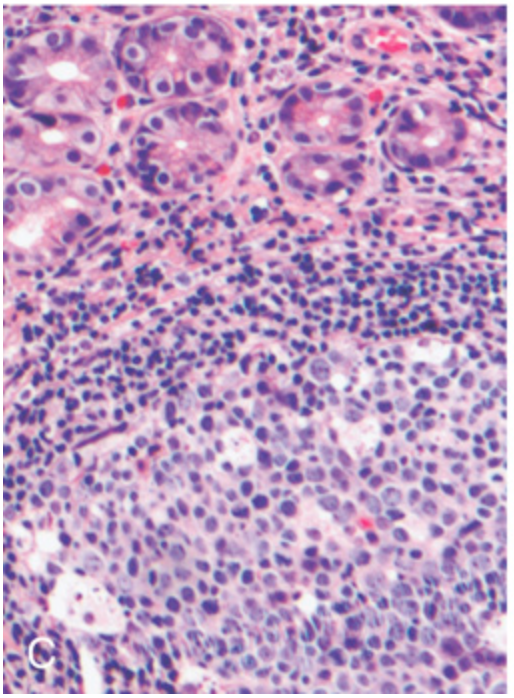

H. pylori gastritis. (C) Lymphoid aggregates with germinal centers and abundant subepithelial plasma cells within the superficial lamina propria are characteristic of H. pylori gastritis.

H. pylori gastritis. (D) Intestinal metaplasia, recognizable as the presence of goblet cells admixed with gastric foveolar epithelium, can develop and is a risk factor for gastric adenocarcinoma.

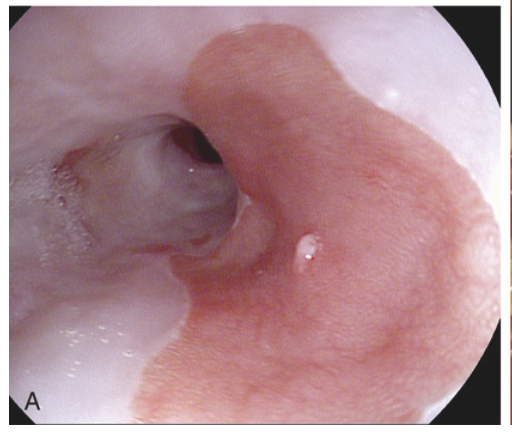

Peptic ulcer disease. (A) Endoscopic view of typical antral ulcer associated with NSAID use.

Peptic ulcer disease. (B) Gross view of a similar ulcer that was resected due to gastric perforation, presenting as free air under the diaphragm. Note the clean edges.

Peptic ulcer disease. (C) The necrotic ulcer base is composed of granulation tissue overlaid by degraded blood.

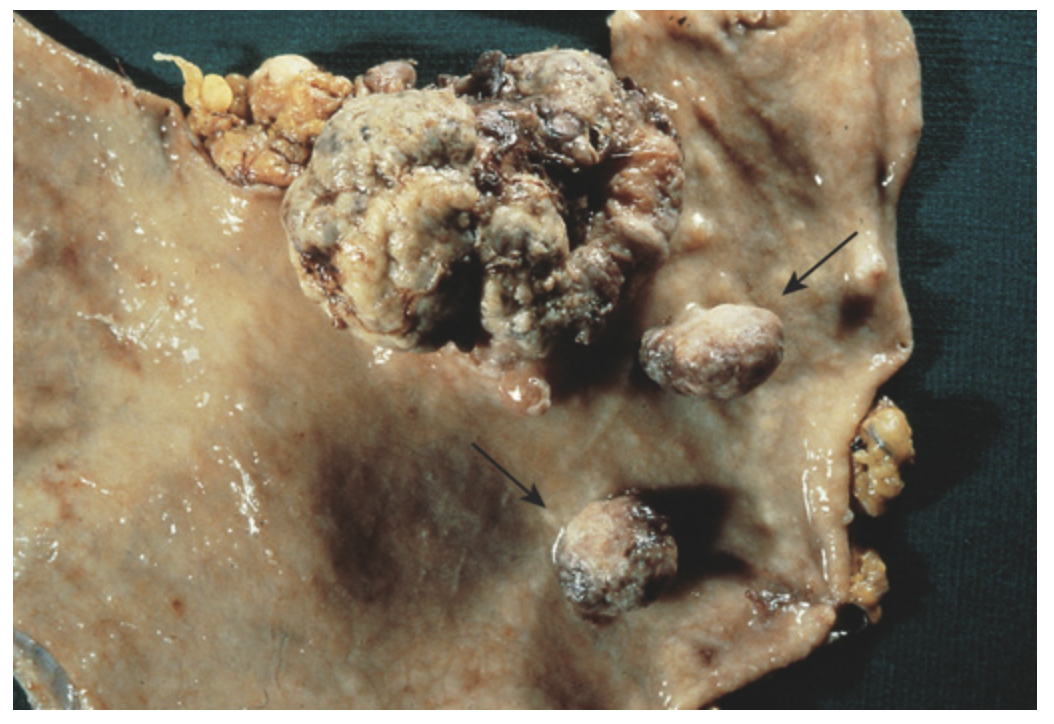

Polypoid gastric adenocarcinoma. In addition to the large adenocarcinoma, two adjacent pedunculated adenomas are present (arrows). Note the absence of rugal folds due to the presence of atrophic gastritis, a risk factor for gastric adenoma and intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinoma.

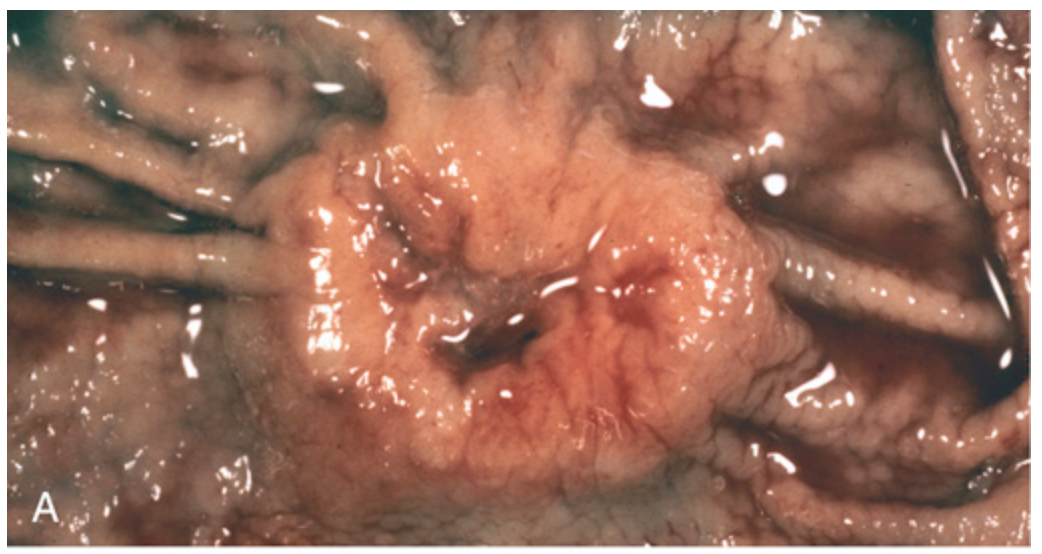

Gastric adenocarcinoma. (A) Intestinal-type adenocarcinoma consisting of an elevated mass with heaped-up borders and central ulceration. Compare with the peptic ulcer in Fig. 13.15A.

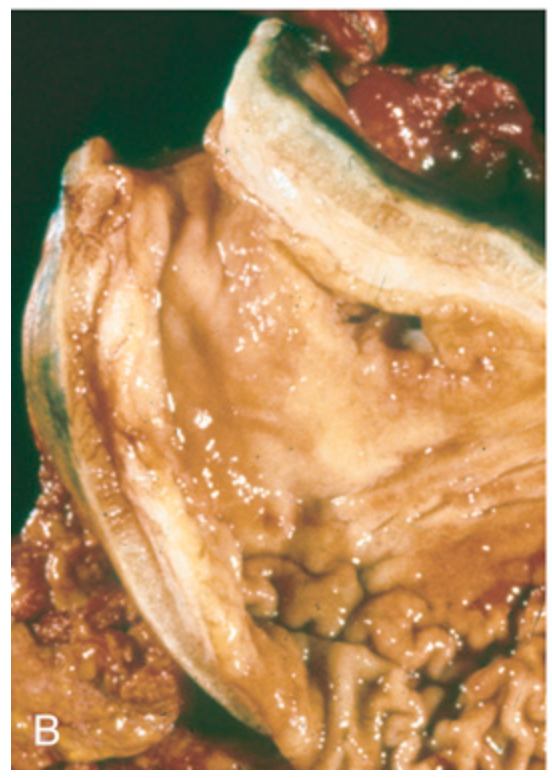

Gastric adenocarcinoma. (B) Linitis plastica due to diffuse adenocarcinoma. The gastric wall is markedly thickened, and rugal folds are partially lost.

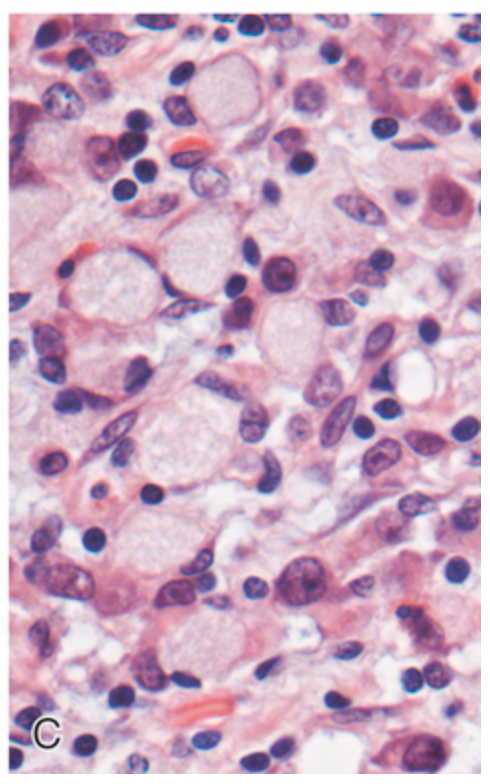

Gastric adenocarcinoma. (C) Signet ring cells in diffuse adenocarcinoma with large cytoplasmic mucin vacuoles and peripherally displaced, crescent-shaped nuclei.

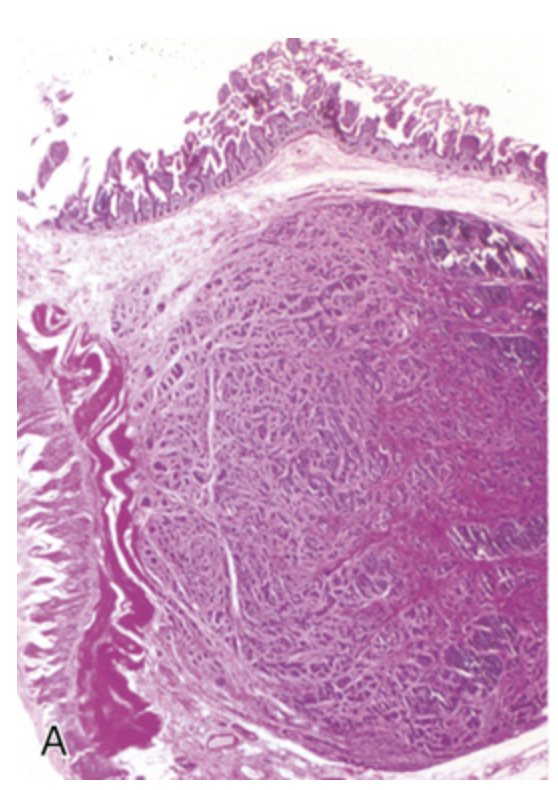

Gastrointestinal carcinoid tumor (neuroendocrine tumor). (A) Carcinoid tumors often form a submucosal nodule composed of tumor cells embedded in dense fibrous tissue.

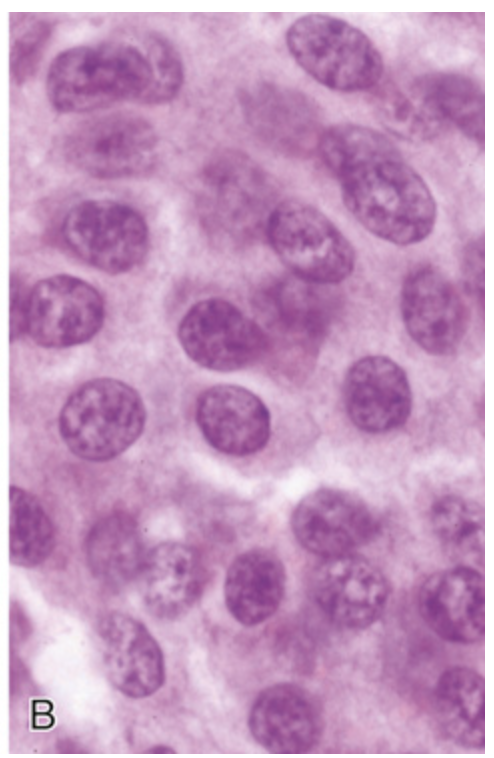

Gastrointestinal carcinoid tumor (neuroendocrine tumor). (B) High magnification shows the bland cytology that typifies neuroendocrine tumors. The chromatin texture, with fine and coarse clumps, frequently assumes a “salt-and-pepper” pattern.

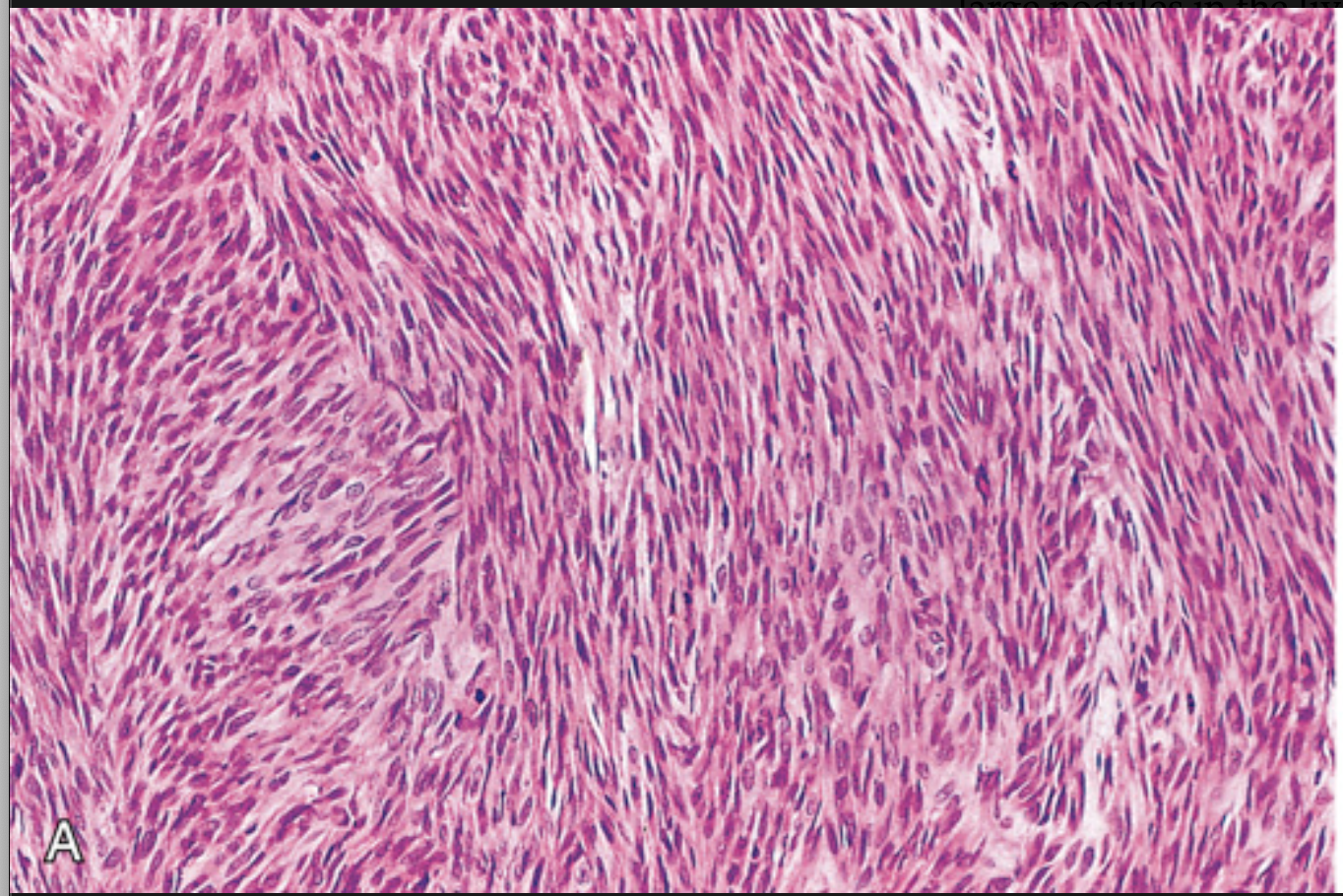

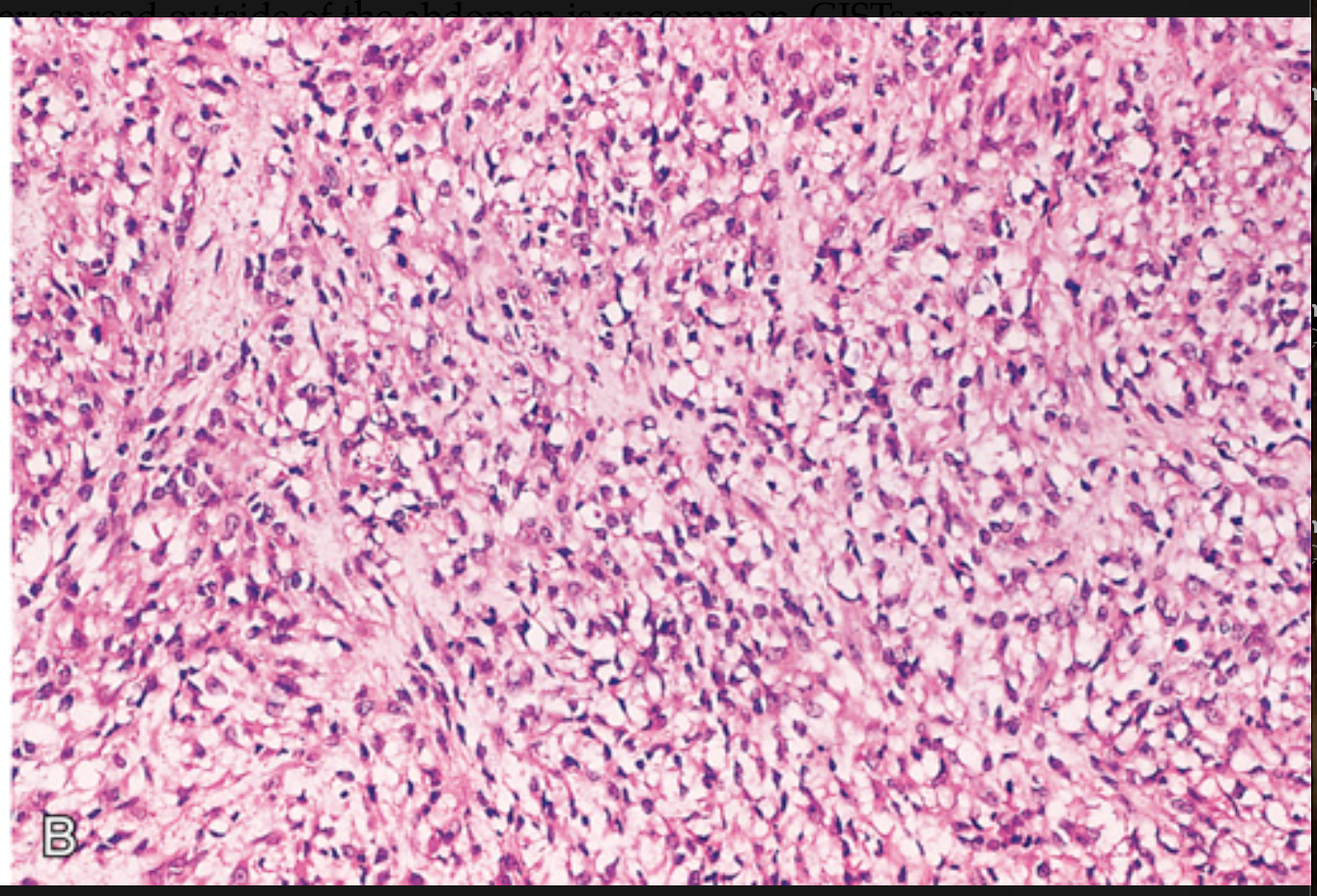

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). (A) Spindle cell type.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). (B) Epithelioid cell type with prominent cytoplasmic vacuoles.

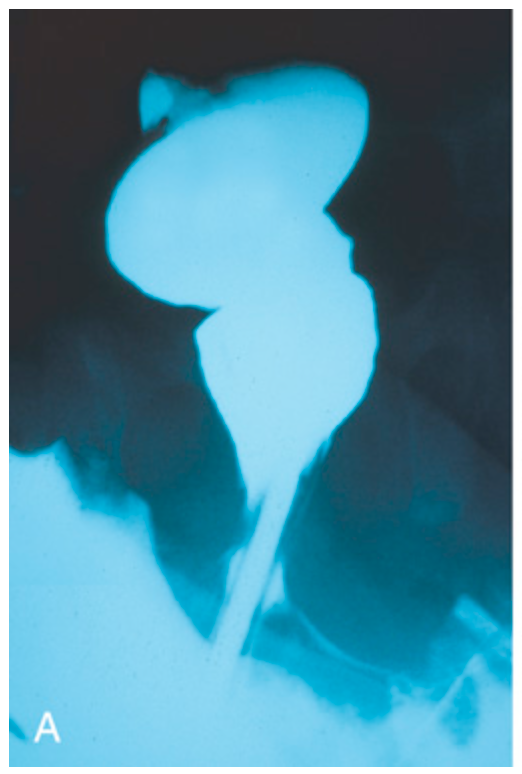

Hirschsprung disease. (A) Preoperative barium enema study showing constricted rectum (bottom) and dilated sigmoid colon. Ganglion cells were absent in the rectum, but present in the sigmoid colon.

Hirschsprung disease. (B) Corresponding intraoperative appearance of the dilated sigmoid colon.

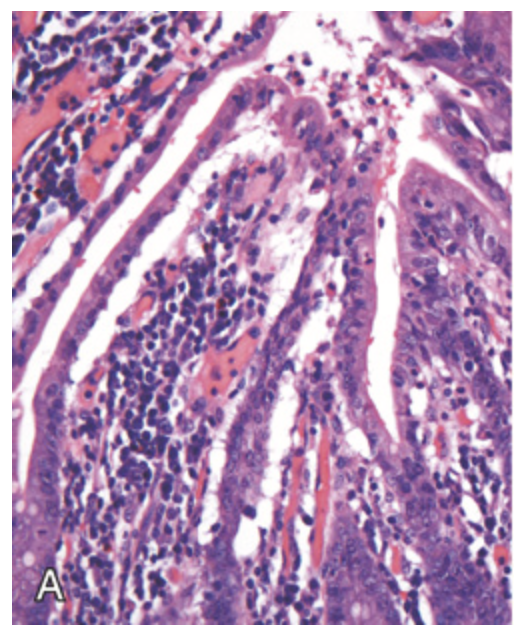

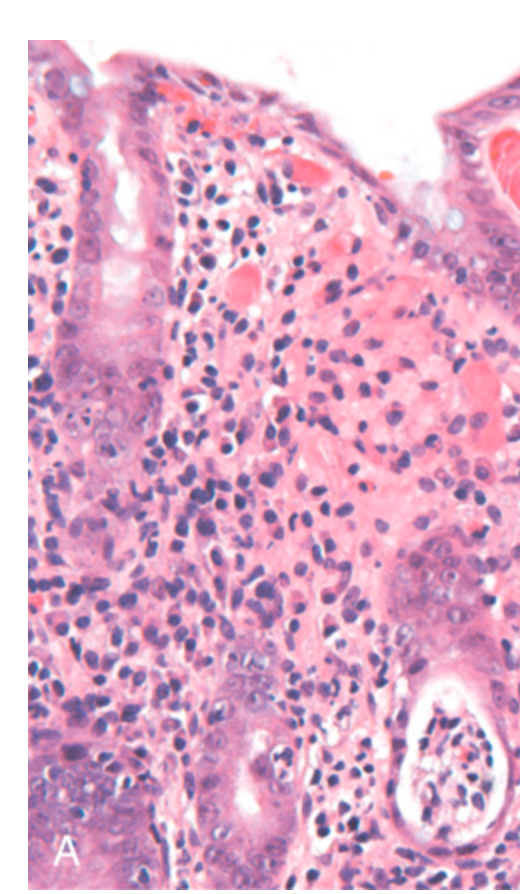

Ischemia. (A) Characteristic attenuated and partially detached villous epithelium in acute jejunal ischemia. Note the hyperchromatic nuclei of proliferating crypt cells.

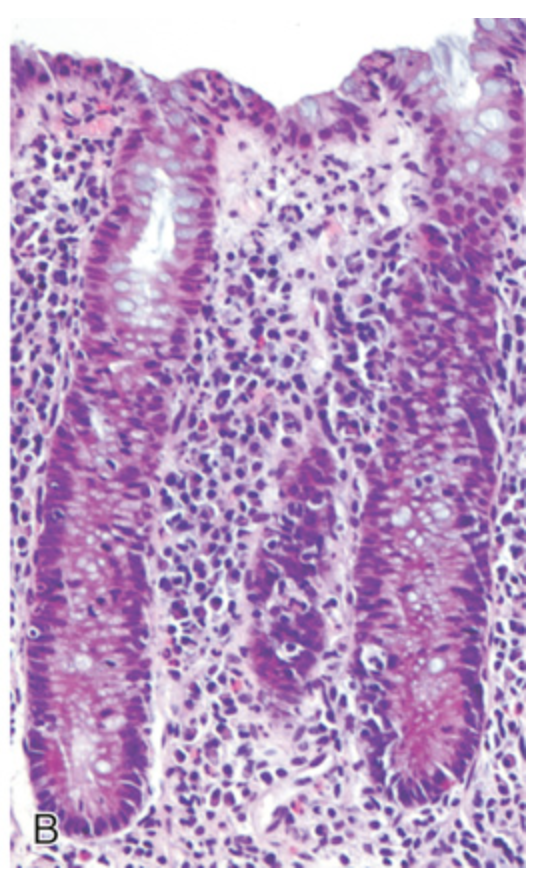

Ischemia. (B) Chronic colonic ischemia with atrophic surface epithelium and fibrotic lamina propria.

Celiac disease. This high power view shows numerous intraepithelial lymphocytes.

Celiac disease. Advanced cases of celiac disease show complete loss of villi, or total villous atrophy. Note the dense plasma cell infiltrates in the lamina propria and intraepithelial lymphocytes.

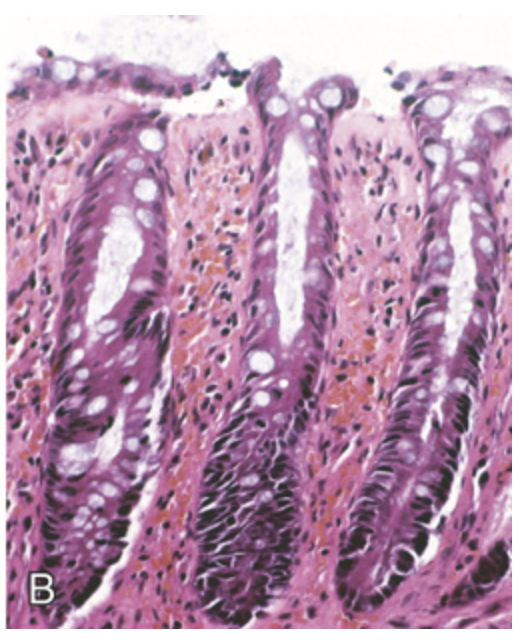

Bacterial enterocolitis. (A) Campylobacter jejuni infection produces acute, self-limited colitis. Neutrophils can be seen within surface and crypt epithelium, and a crypt abscess is present (lower right).

Bacterial enterocolitis. (B) Enteroinvasive Escherichia coli infection is similar to other acute, self-limited colitides. Note the maintenance of normal crypt architecture and spacing, despite abundant intraepithelial neutrophils.

Clostridioides difficile colitis. (A) The colon is coated by tan pseudomembranes composed of neutrophils, dead epithelial cells, and inflammatory debris (endoscopic view).

Clostridioides difficile colitis. (B) Typical pattern of neutrophils emanating from a crypt is reminiscent of a volcanic eruption.

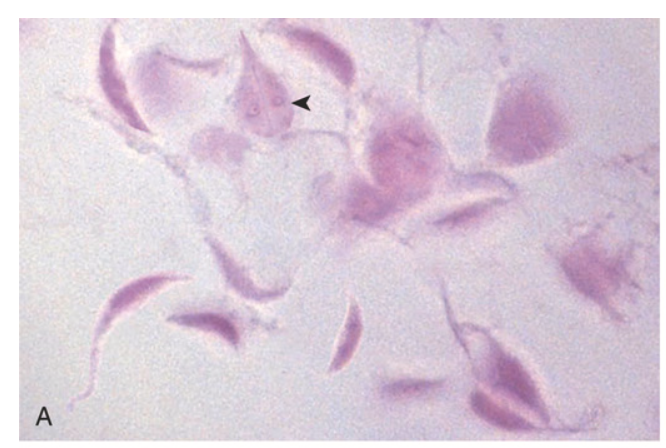

Gastrointestinal parasites. (A) Giardia lamblia organisms, seen in a stool prep. A characteristic trophozoite is marked by the arrowhead.

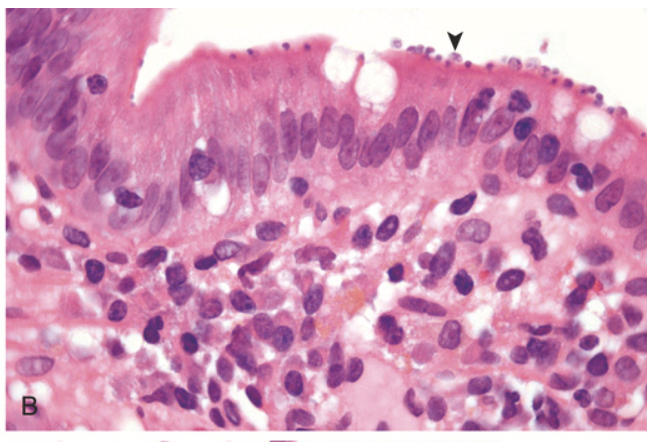

Gastrointestinal parasites. (B) Cryptosporidium organisms (arrowhead) are seen coating the surface of epithelial cells in the small bowel.

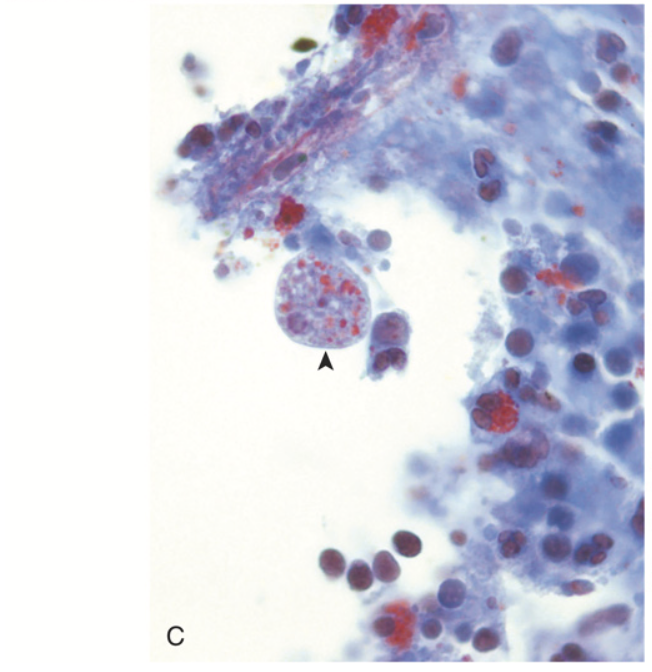

Gastrointestinal parasites. (C) Entamoeba histolytica. The left panel shows an amoeba that has phagocytosed red cells (arrowhead, trichrome stain).

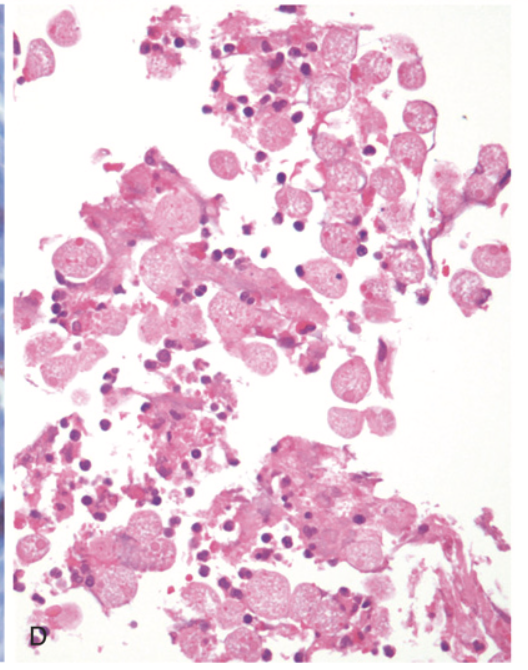

Gastrointestinal parasites. (D) shows a large cluster of amoebae within an area of colonic ulceration.

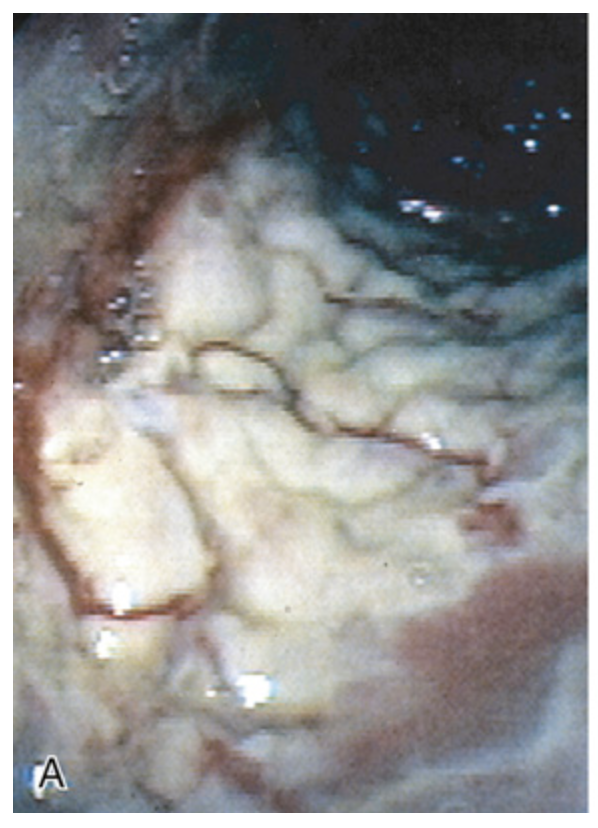

Sigmoid diverticular disease. (A) Endoscopic view of two sigmoid diverticula. Compare to (B).

Sigmoid diverticular disease. (B) Gross examination of a resected sigmoid colon shows regularly spaced stool-filled diverticula.

Sigmoid diverticular disease. (C) Cross-section showing the outpouching of mucosa beneath the muscularis propria.

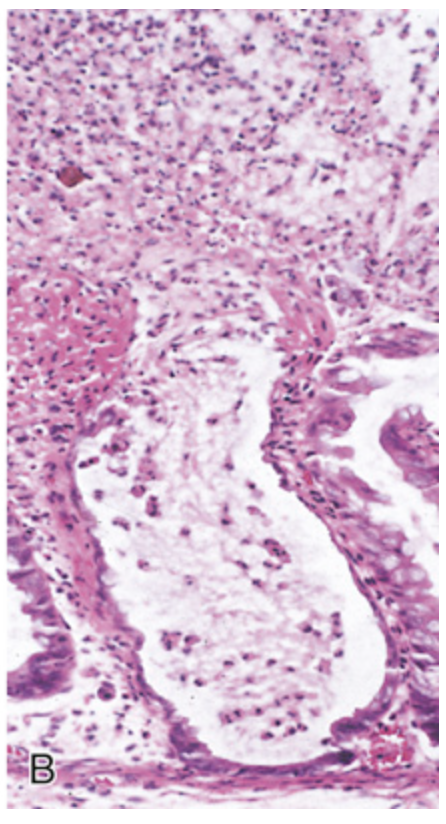

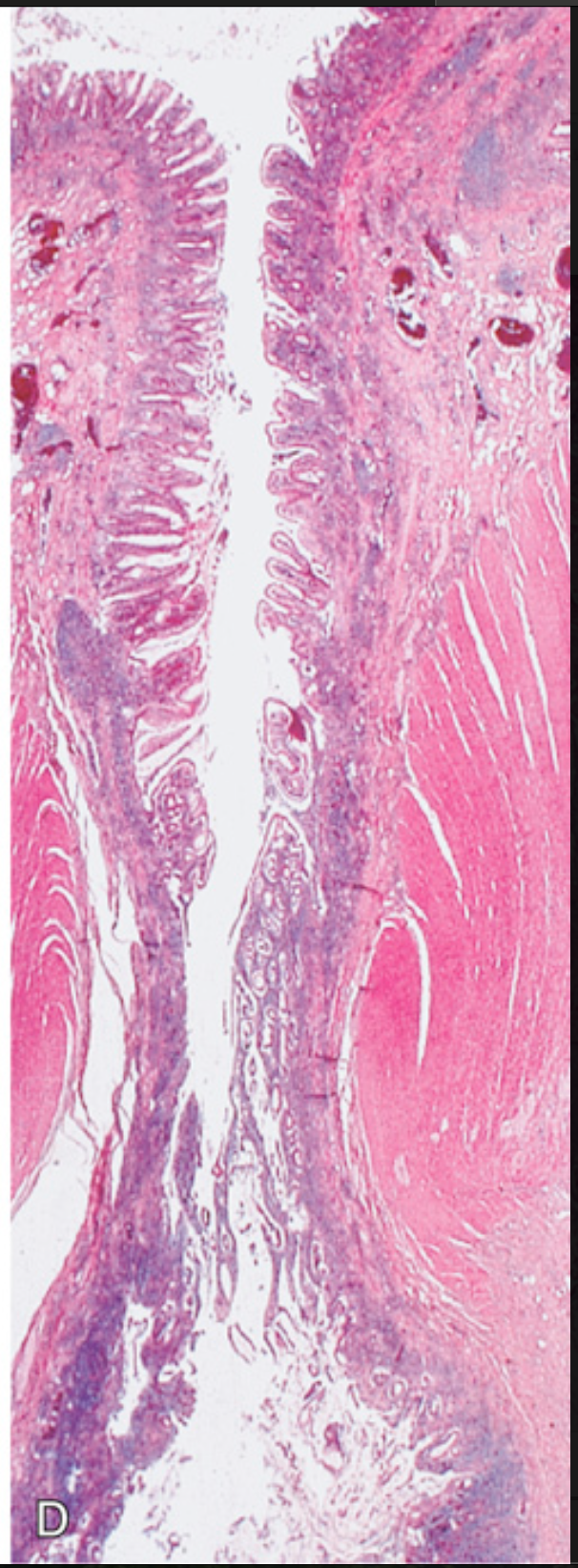

Sigmoid diverticular disease. (D) Low-power photomicrograph of a sigmoid diverticulum showing protrusion of the mucosa and submucosa through the muscularis propria.

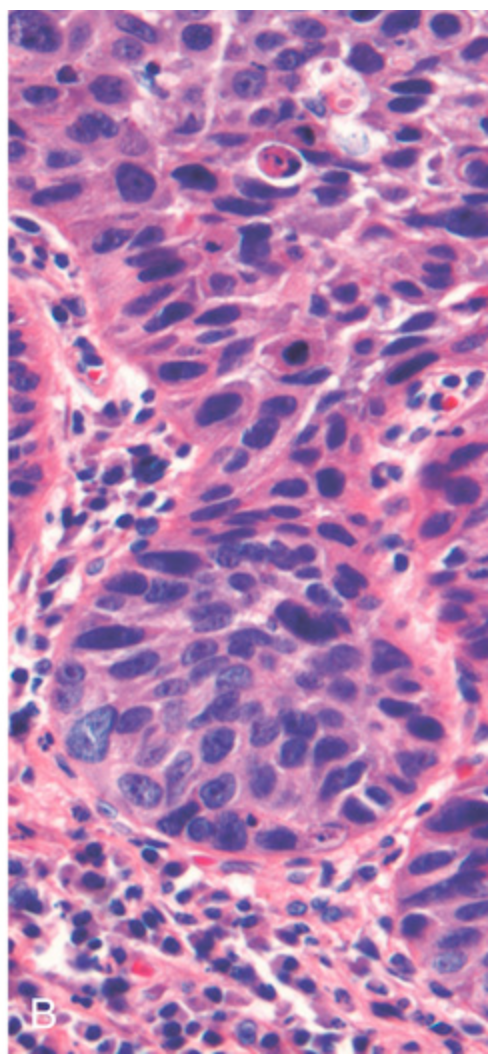

Microscopic pathology of Crohn disease. (A) Haphazard crypt organization results from repeated injury and regeneration.

Microscopic pathology of Crohn disease. (B) Noncaseating granuloma.

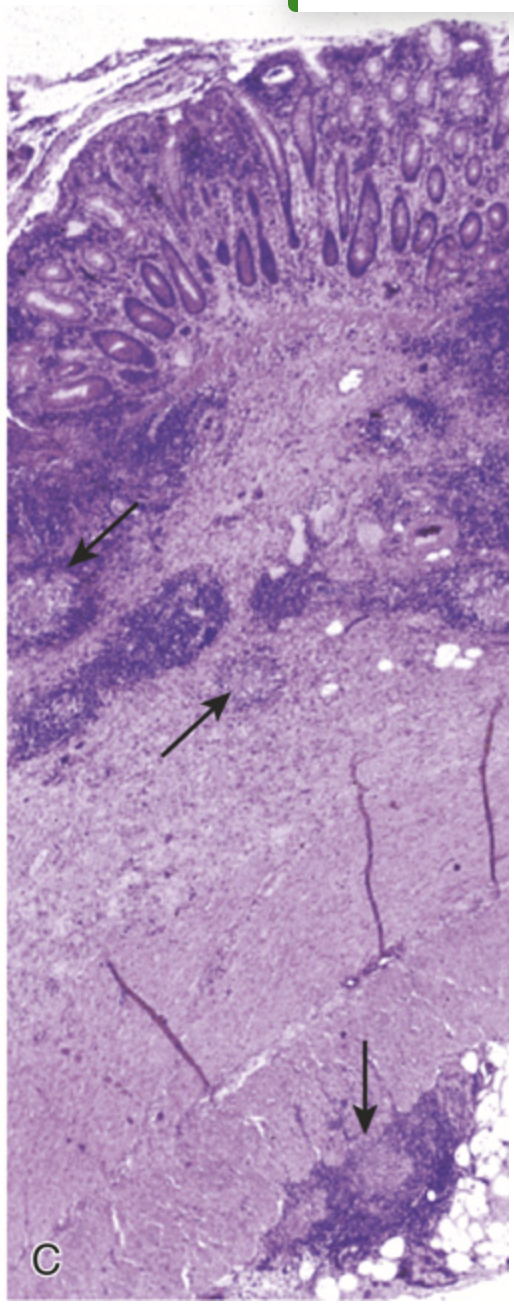

Microscopic pathology of Crohn disease. (C) Transmural Crohn disease with markedly thickened wall and submucosal and serosal granulomas (arrows).

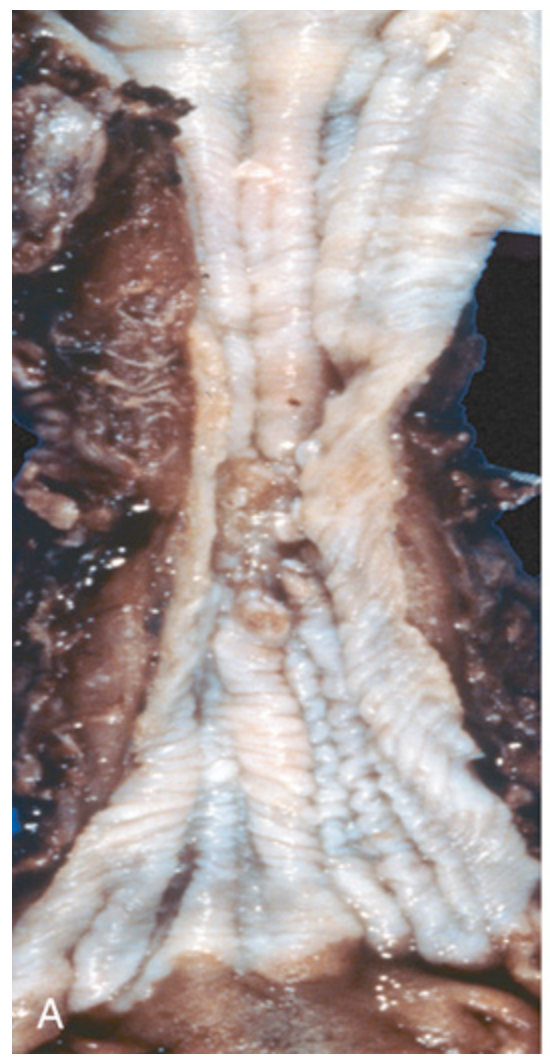

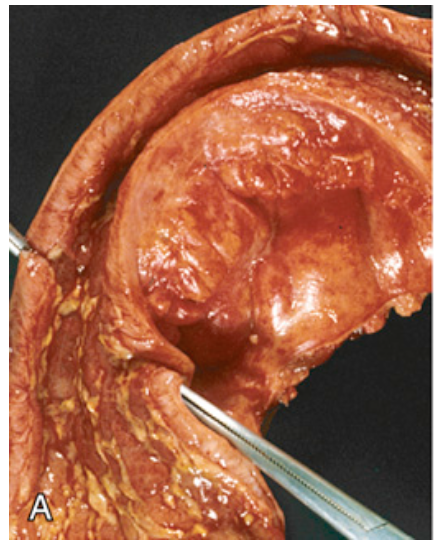

Gross pathology of Crohn disease. (A) Small-intestinal stricture.

Gross pathology of Crohn disease. (B) Linear mucosal ulcers and thickened intestinal wall.

Gross pathology of Crohn disease. (C) Creeping fat.

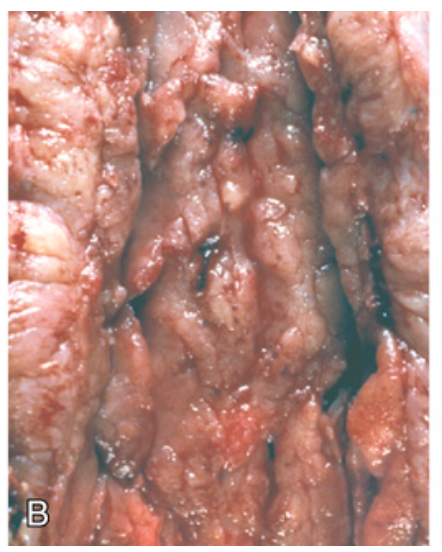

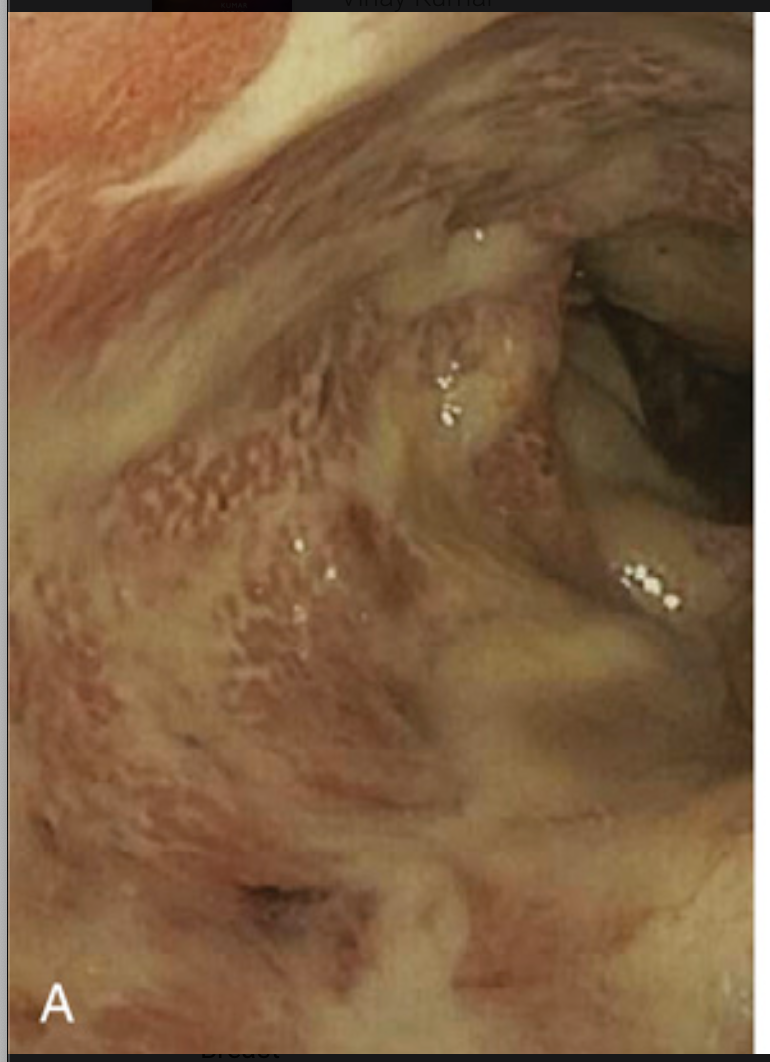

Pathology of ulcerative colitis. (A) Endoscopic view of severe ulcerative colitis with ulceration and adherent mucopurulent material.

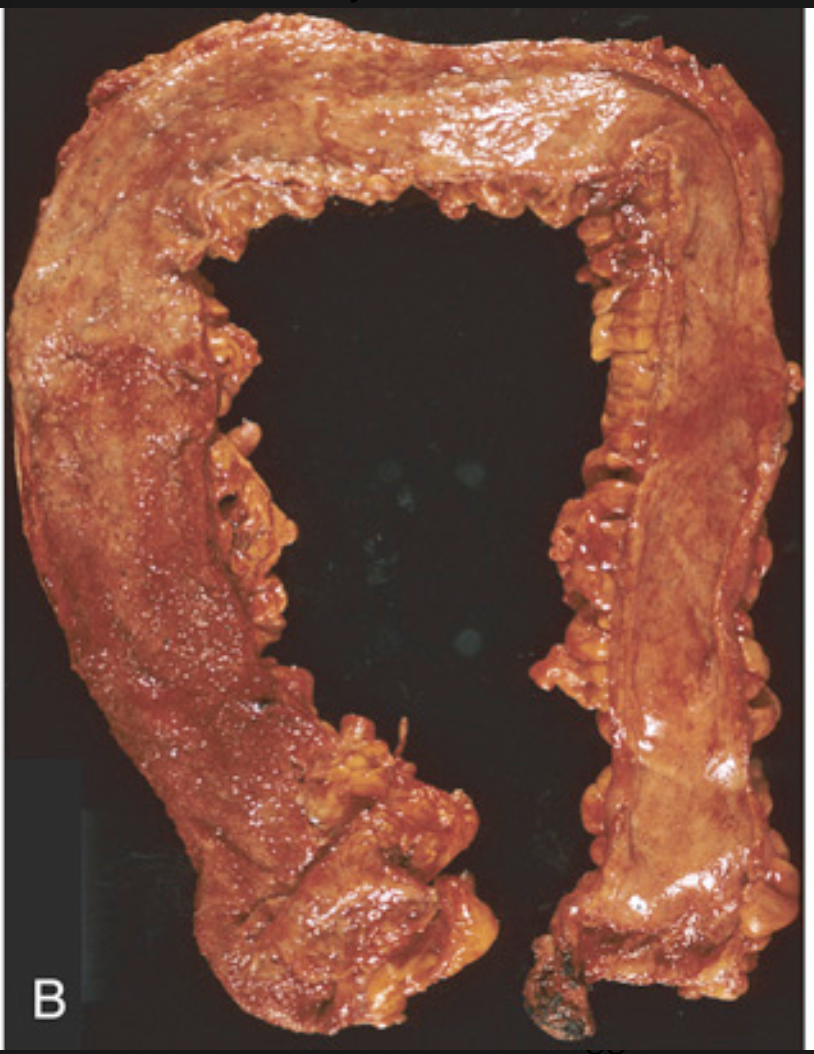

Pathology of ulcerative colitis. (B) Total colectomy with pancolitis showing active disease, with red, granular mucosa in the cecum (left) and smooth, atrophic mucosa distally (right).

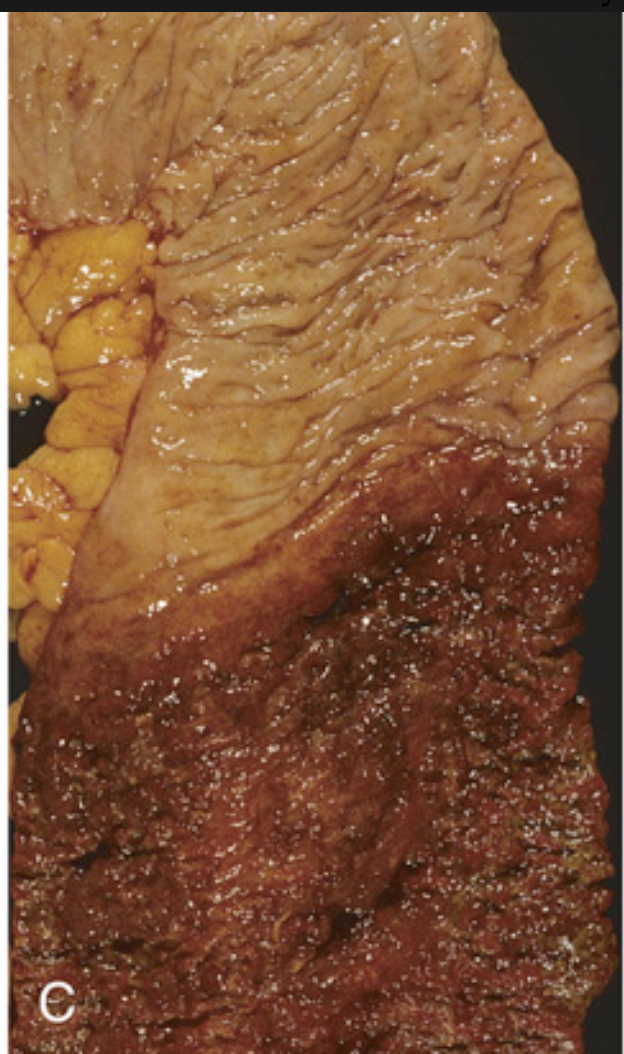

Pathology of ulcerative colitis. (C) Sharp demarcation between active ulcerative colitis (bottom) and normal (top).

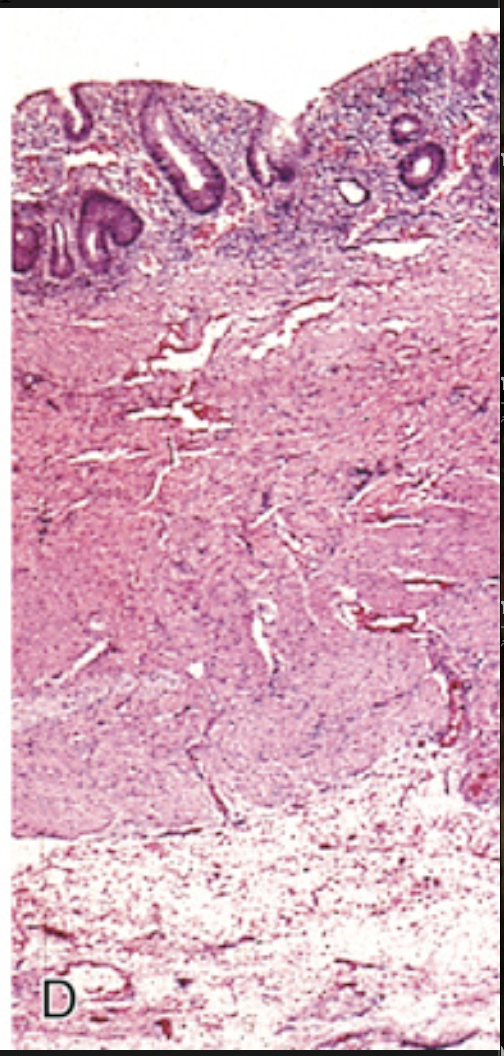

Pathology of ulcerative colitis. (D) This full-thickness histologic section shows that disease is limited to the mucosa. Compare with Fig. 13.29C.

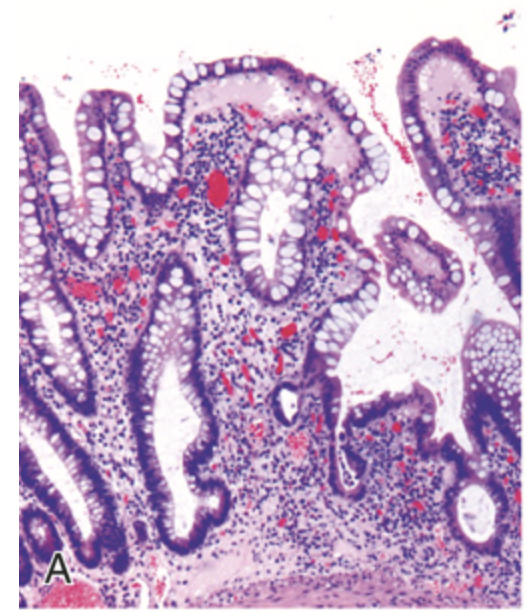

Hamartomatous polyps. (A) Juvenile polyp. Note the surface erosion and cystically dilated crypts filled with mucus, neutrophils, and debris.

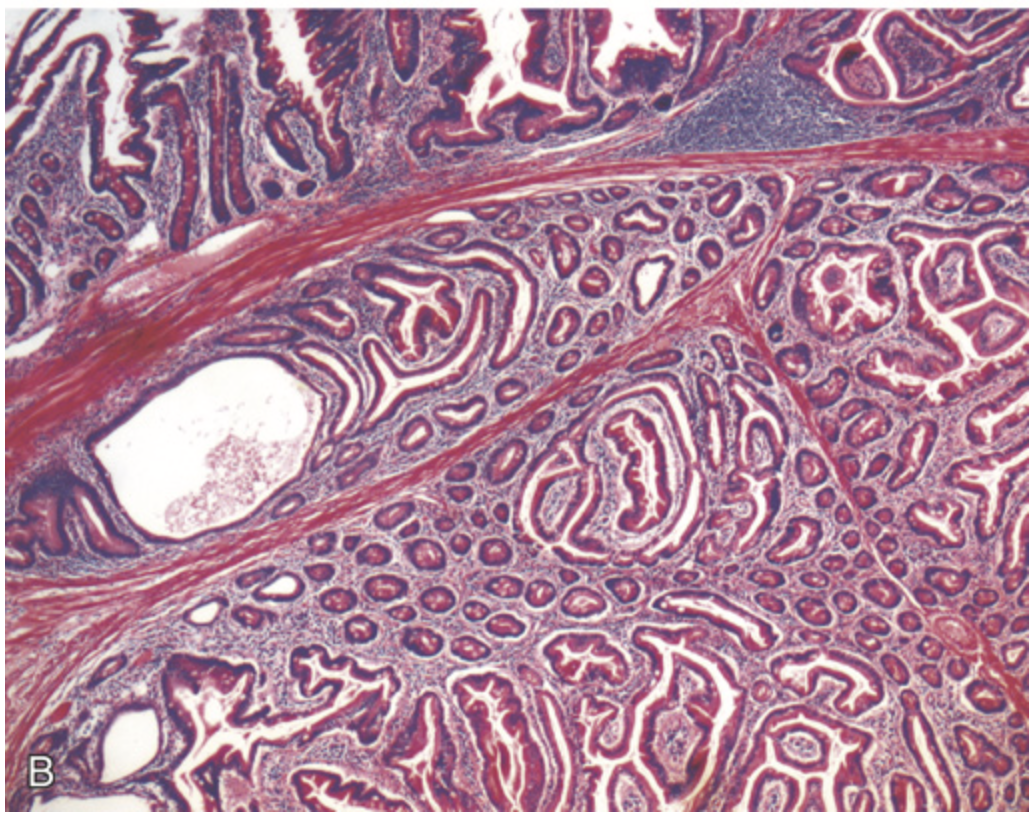

Hamartomatous polyps. (B) Peutz-Jeghers polyp. Complex glandular architecture and bundles of smooth muscle help to distinguish Peutz-Jeghers polyps from juvenile polyps.

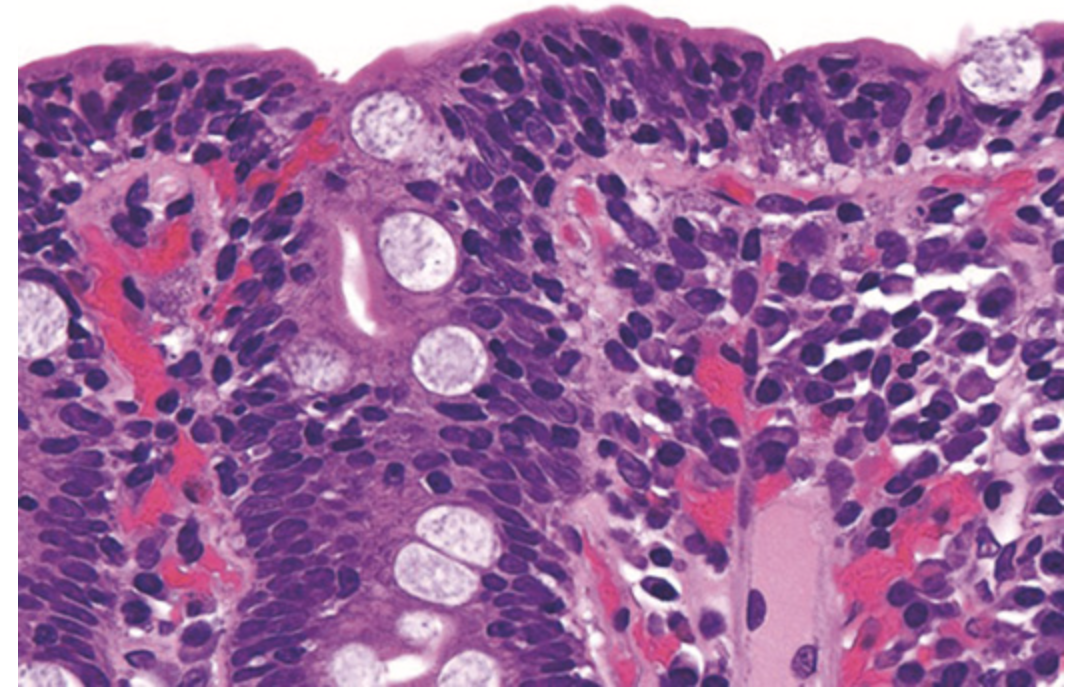

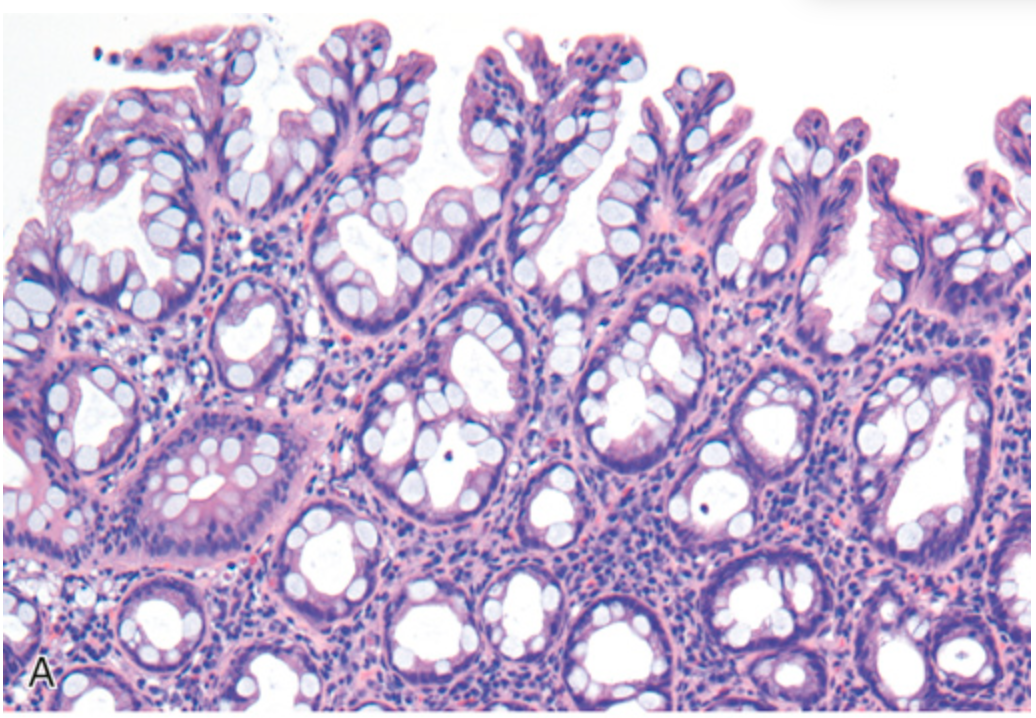

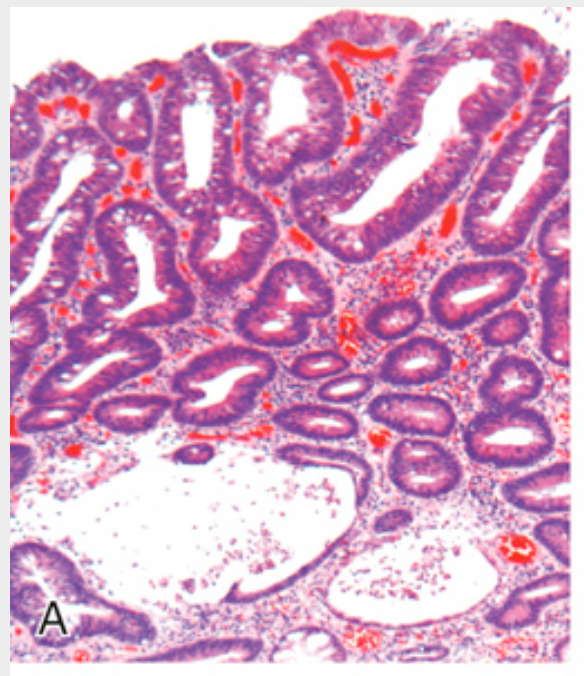

Hyperplastic polyp. (A) Polyp surface with irregular tufting of epithelial cells.

Hyperplastic polyp. (B) Tufting results from epithelial overcrowding.

Hyperplastic polyp. (C) Epithelial crowding produces a serrated architecture when glands are cut in cross-section.

Colonic adenomas. (A) Pedunculated adenoma (endoscopic view).

Colonic adenomas. (B) Adenoma with a velvety surface.

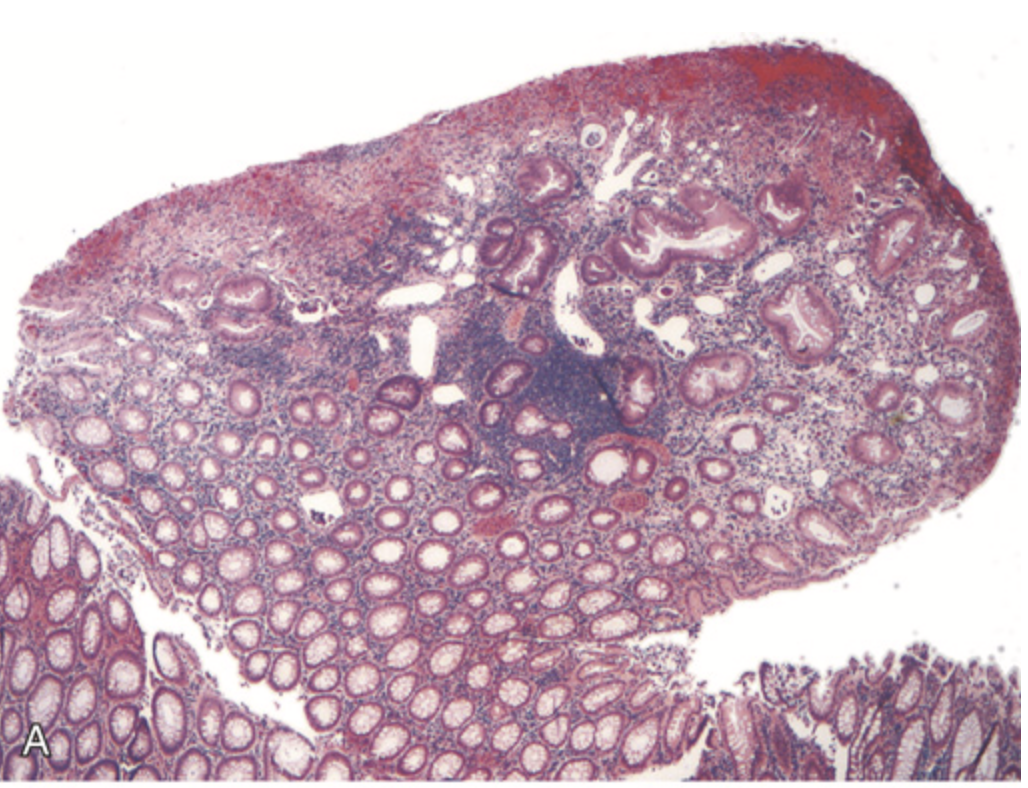

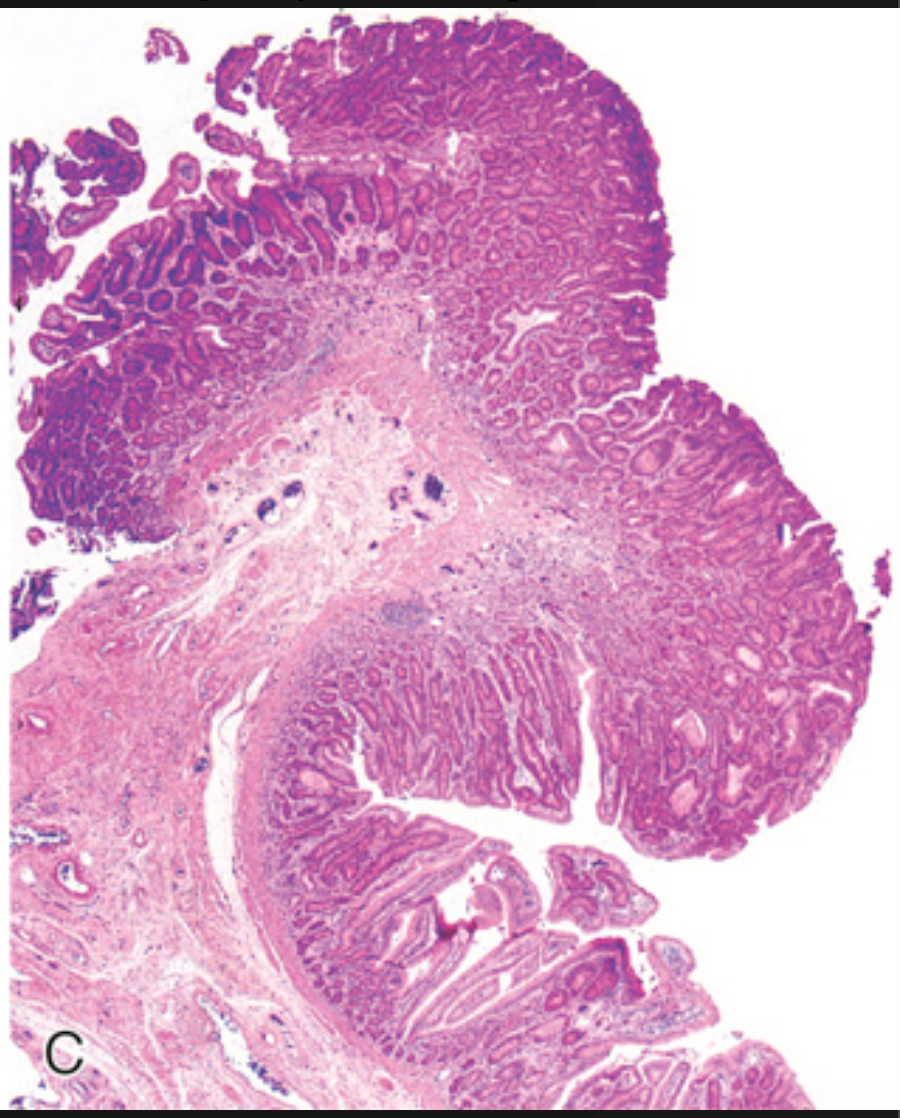

Colonic adenomas. (C) Low-magnification photomicrograph of a pedunculated tubular adenoma

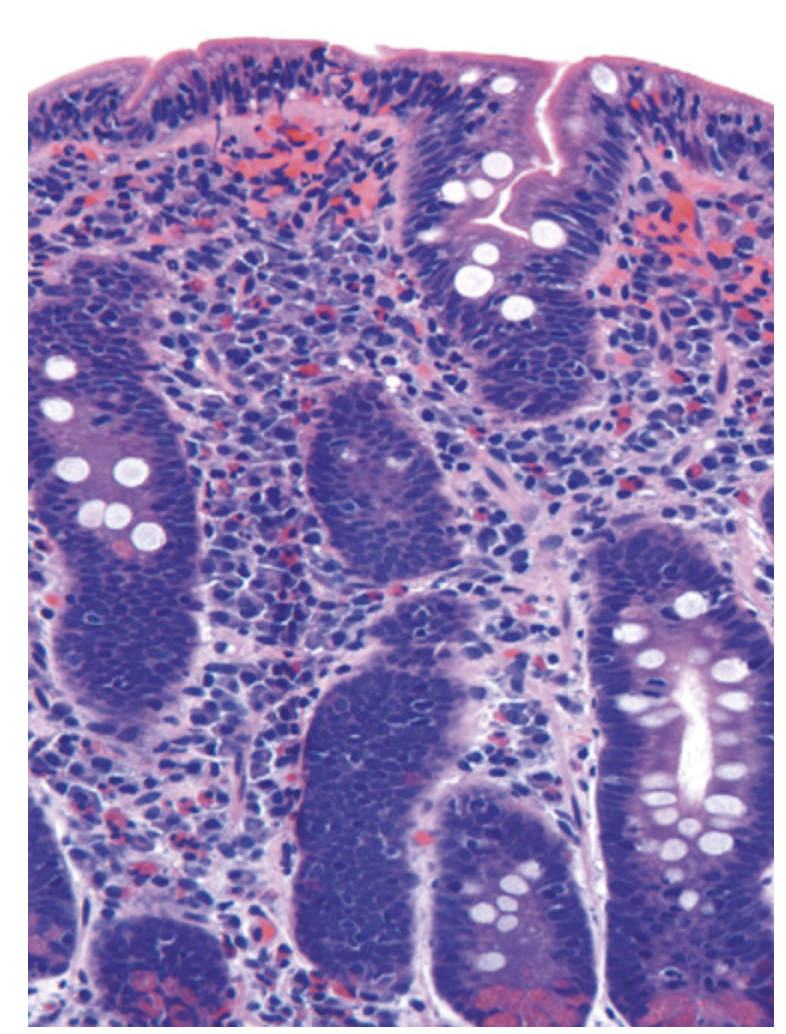

Histologic appearance of colonic adenomas. (A) Tubular adenoma with a smooth surface and rounded glands. In this case, crypt dilation and rupture, with associated reactive inflammation, can be seen at the bottom of the field.

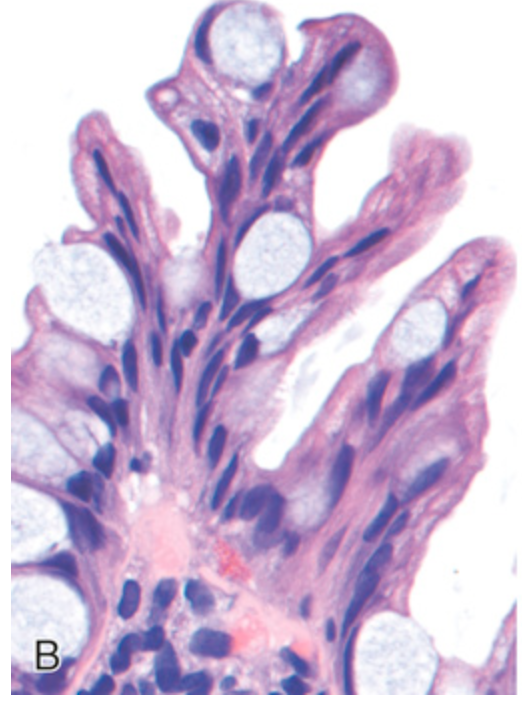

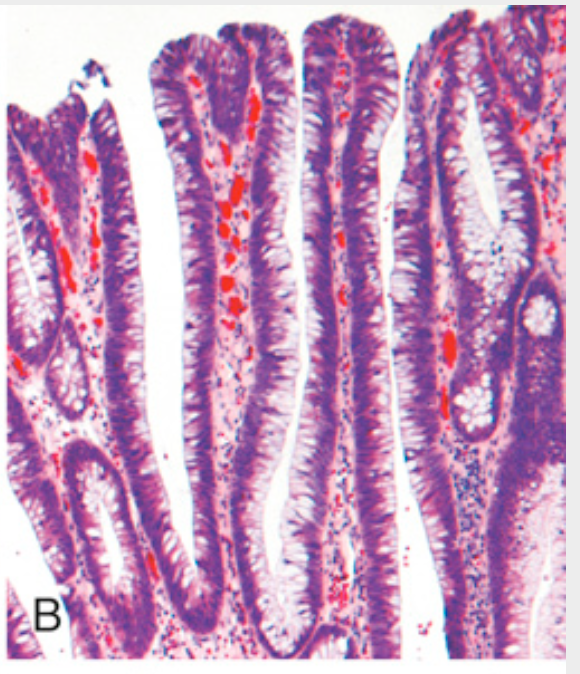

Histologic appearance of colonic adenomas. (B) Villous adenoma with long, slender projections that are reminiscent of small-intestinal villi.

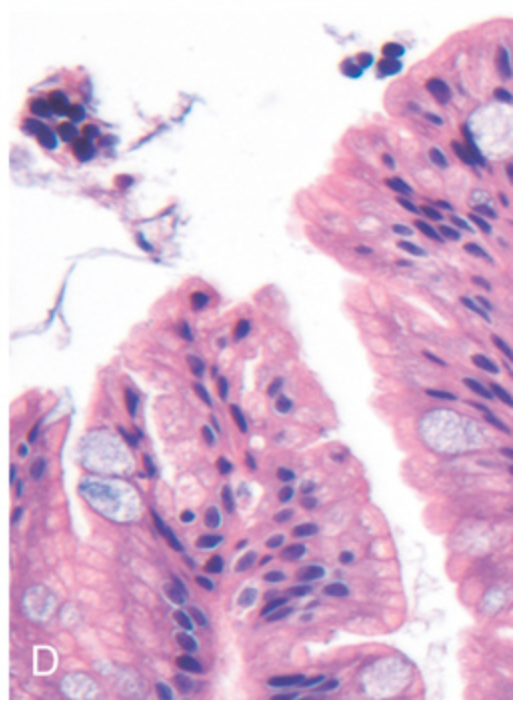

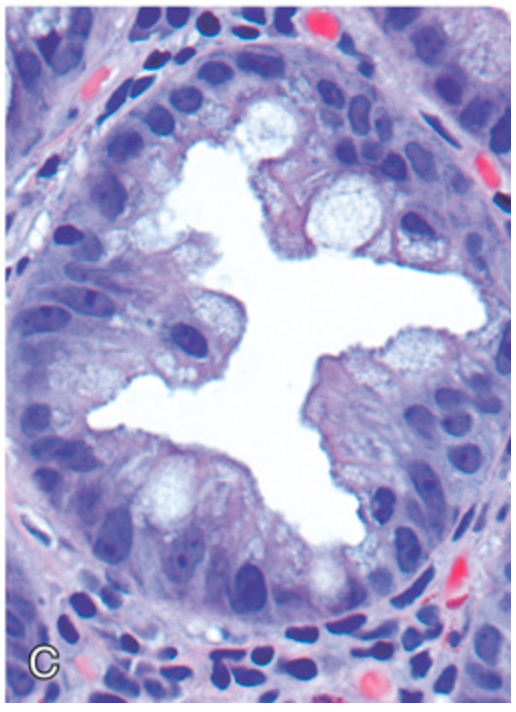

Histologic appearance of colonic adenomas. (C) Dysplastic epithelial cells (top) with an increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, hyperchromatic and elongated nuclei, and nuclear pseudostratification. Compare with the nondysplastic epithelium (bottom).

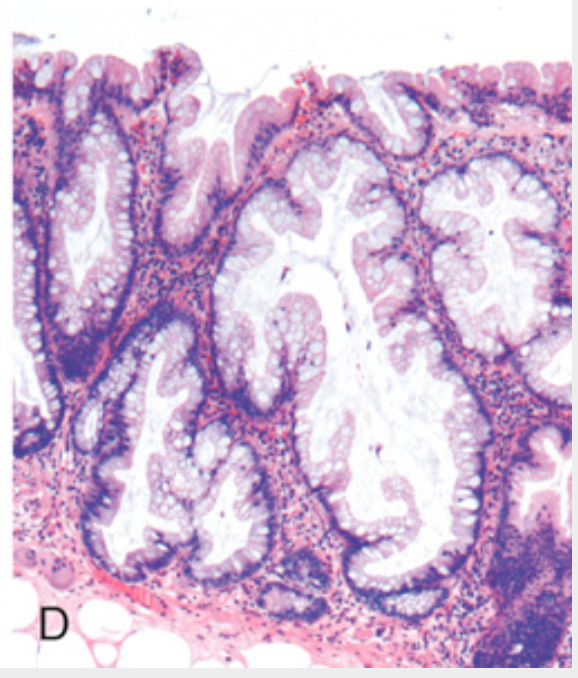

Histologic appearance of colonic adenomas. (D) Sessile serrated adenoma lined by goblet cells without typical cytologic features of dysplasia. This lesion is distinguished from a hyperplastic polyp by involvement of the crypts. Compare with the hyperplastic polyp in Fig. 13.32.

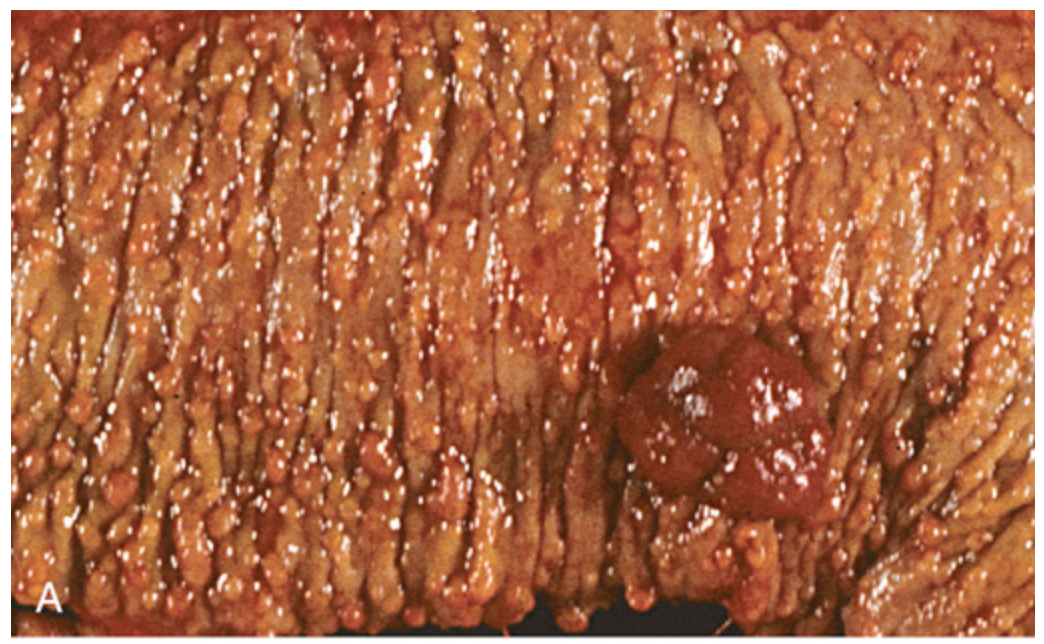

Familial adenomatous polyposis. (A) Hundreds of small colonic polyps are present along with a dominant polyp (right).

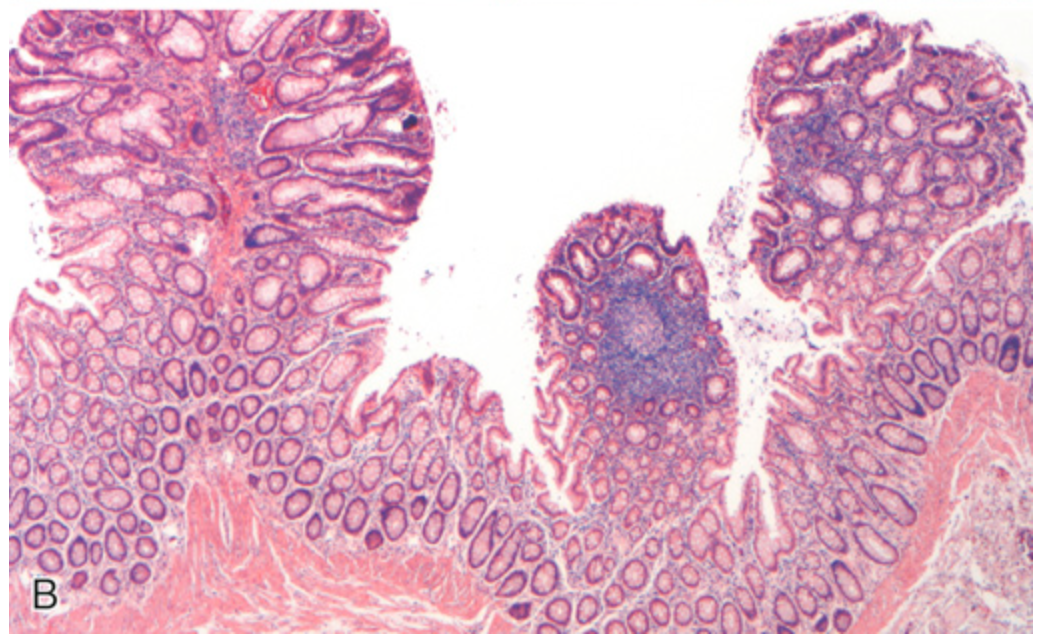

Familial adenomatous polyposis. (B) Three tubular adenomas are present in this single microscopic field.

Colorectal carcinoma. (A) Endoscopic view of ulcerated ascending colon adenocarcinoma.

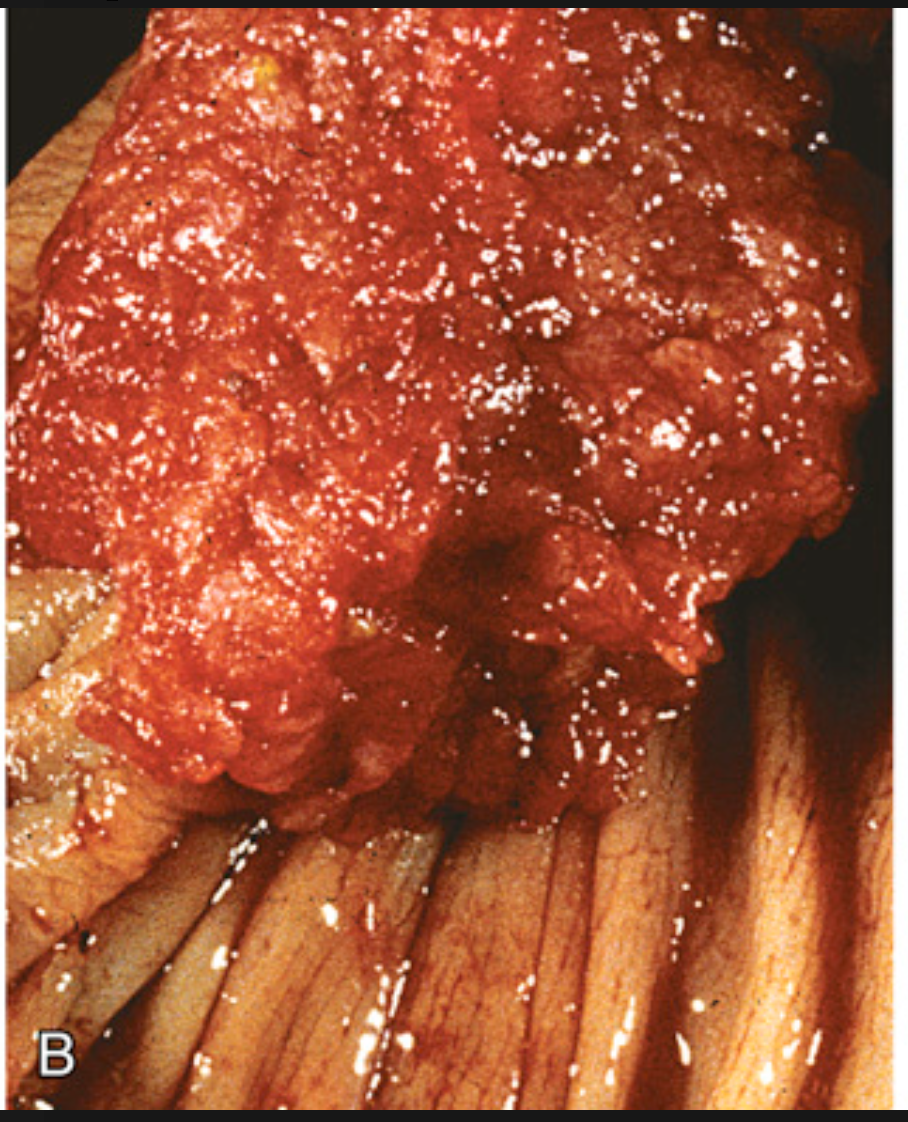

Colorectal carcinoma. (B) Resected rectum showing a circumferential adenocarcinoma. Note the anal mucosa at the bottom of the image.

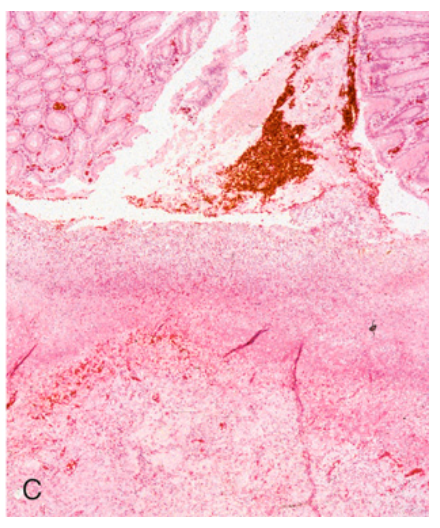

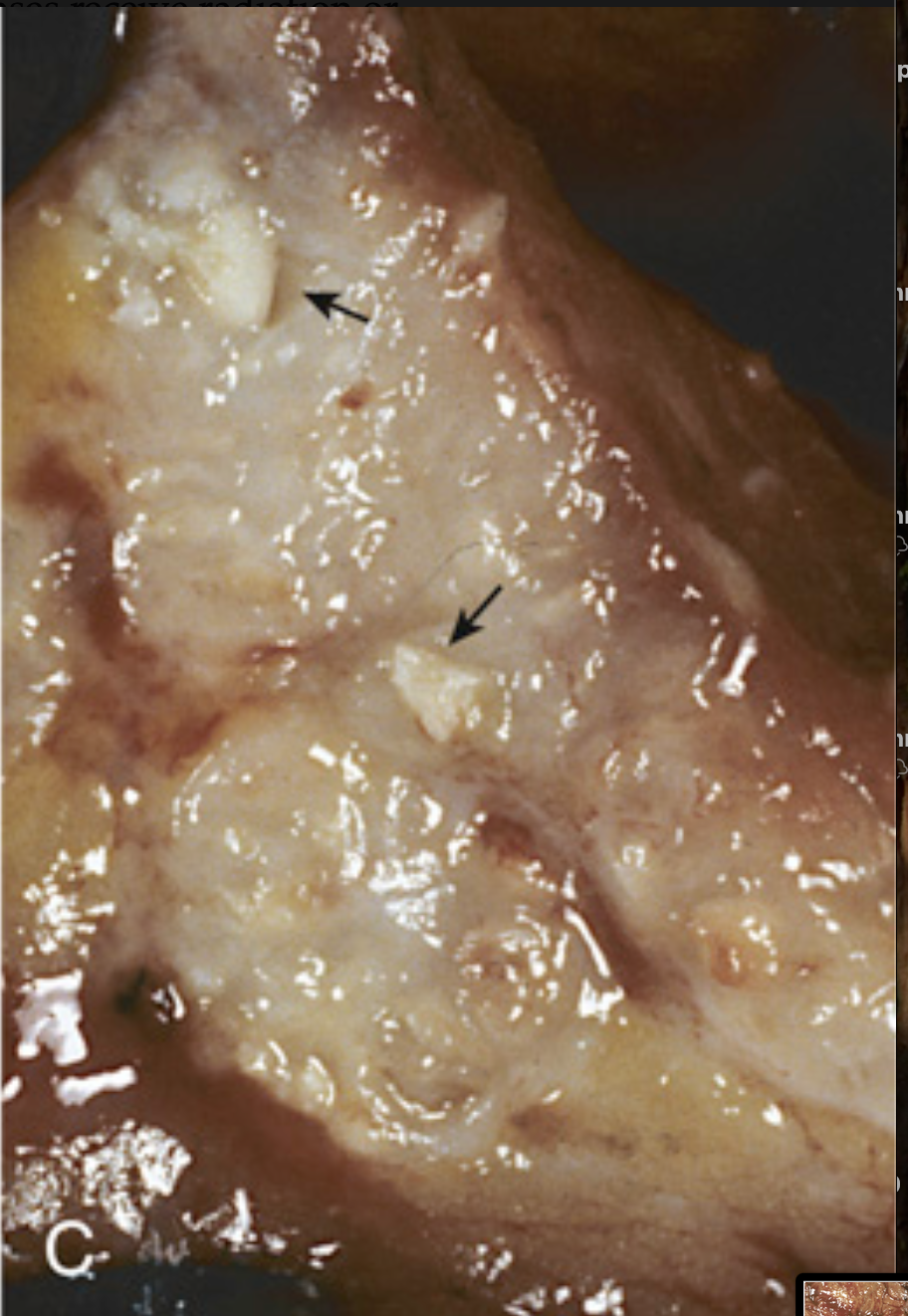

Colorectal carcinoma. (C) Cancer of the sigmoid colon that has invaded through the muscularis propria and is present within subserosal adipose tissue (left). Areas of chalky necrosis are present within the colon wall (arrows).

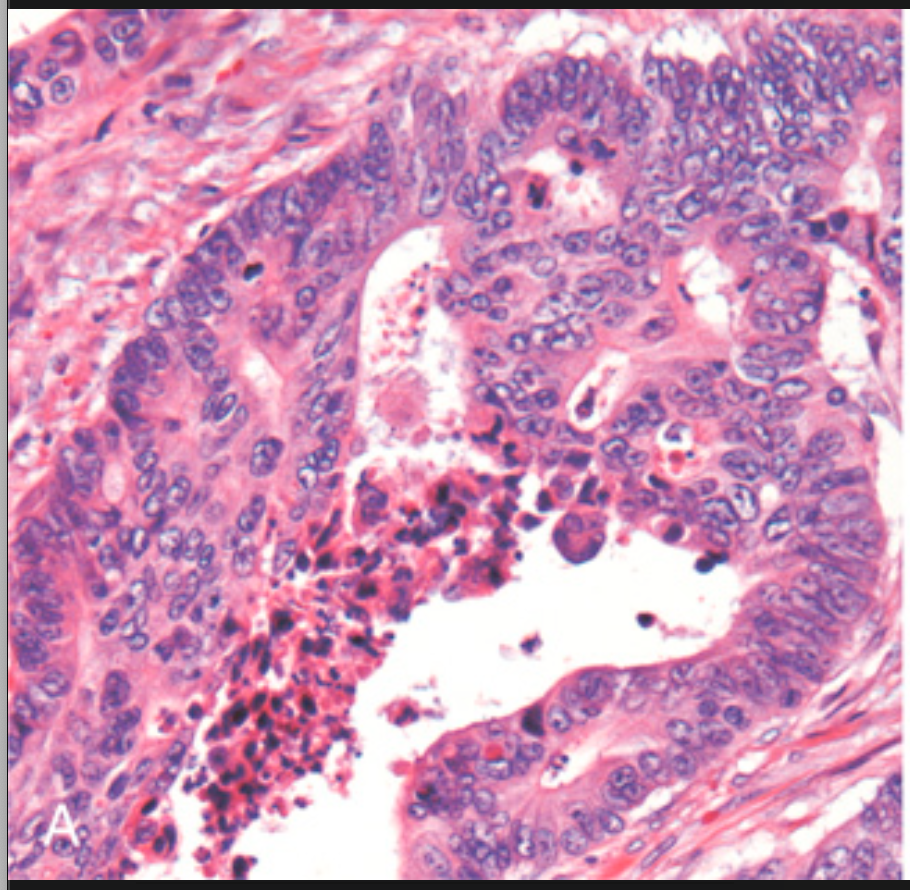

Histologic appearance of colorectal carcinoma. (A) Well-differentiated adenocarcinoma. Note the elongated, hyperchromatic nuclei. Necrotic debris, present in the gland lumen, is typical.

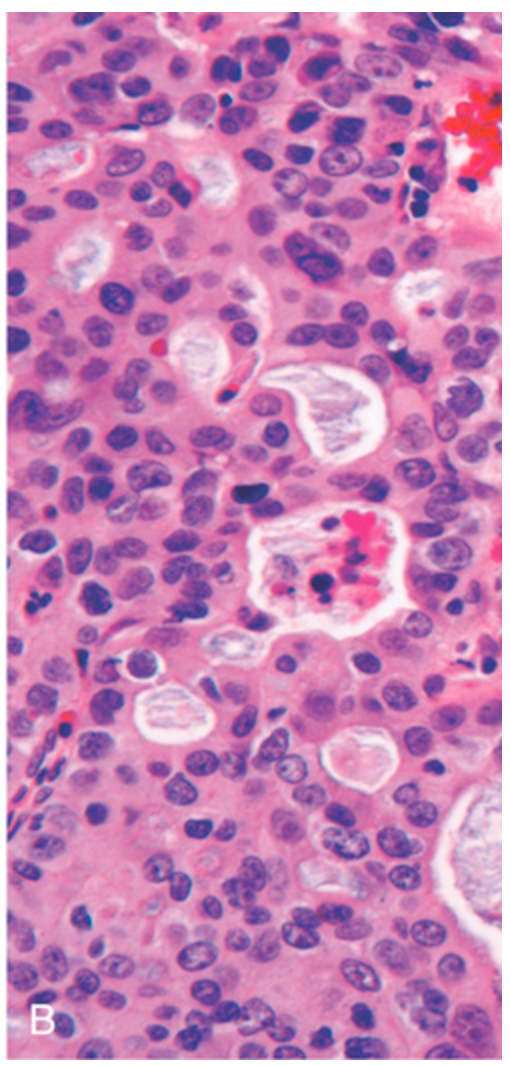

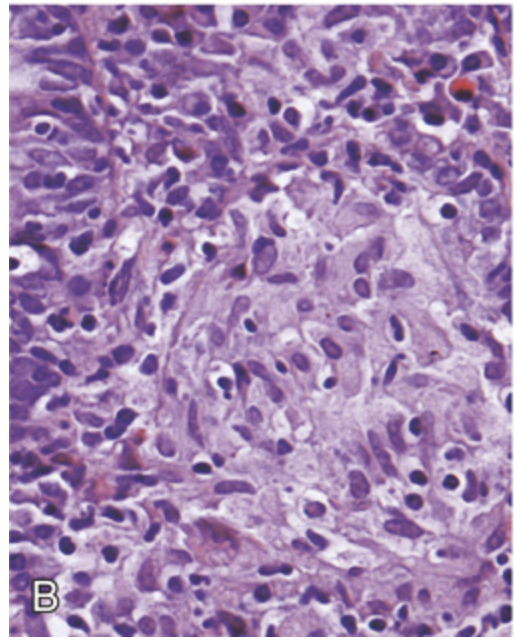

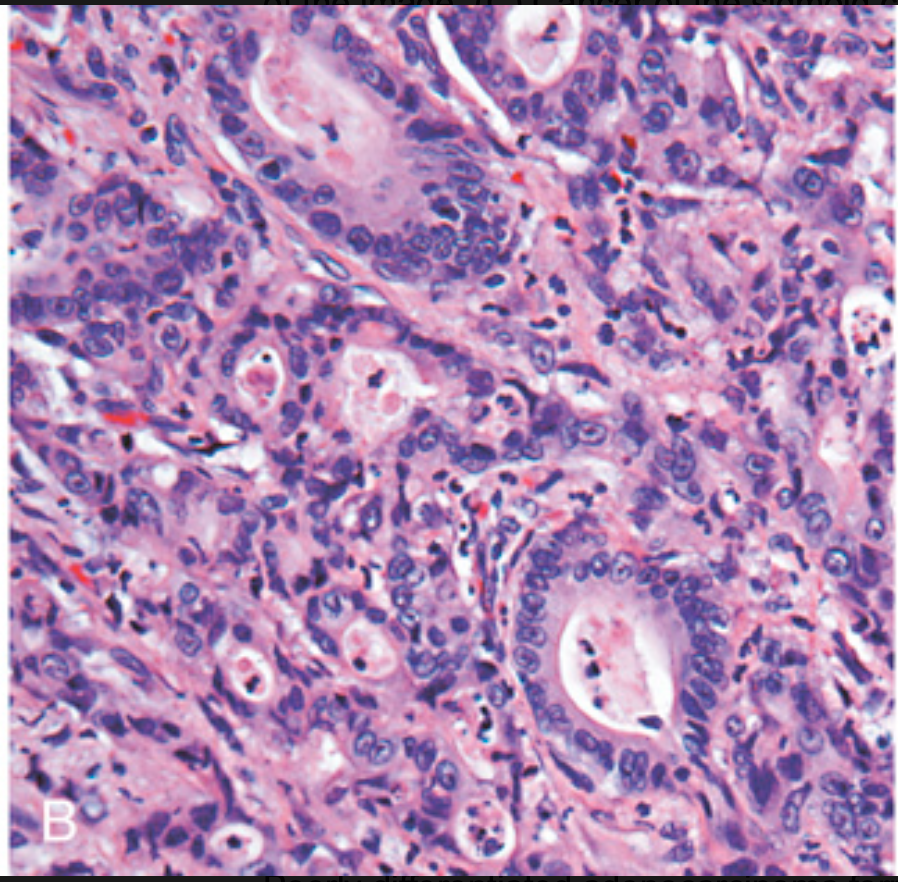

Histologic appearance of colorectal carcinoma. (B) Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma forms a few glands but is largely composed of infiltrating nests of tumor cells.

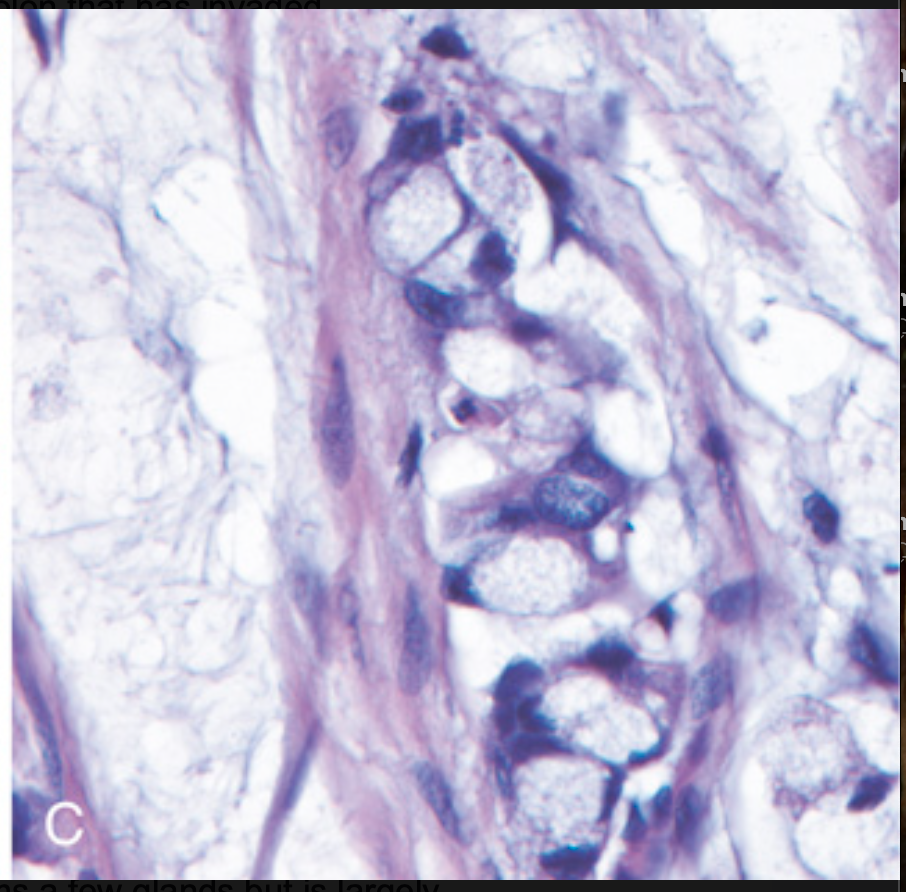

Histologic appearance of colorectal carcinoma. (C) Mucinous adenocarcinoma with signet ring cells and extracellular mucin pools.

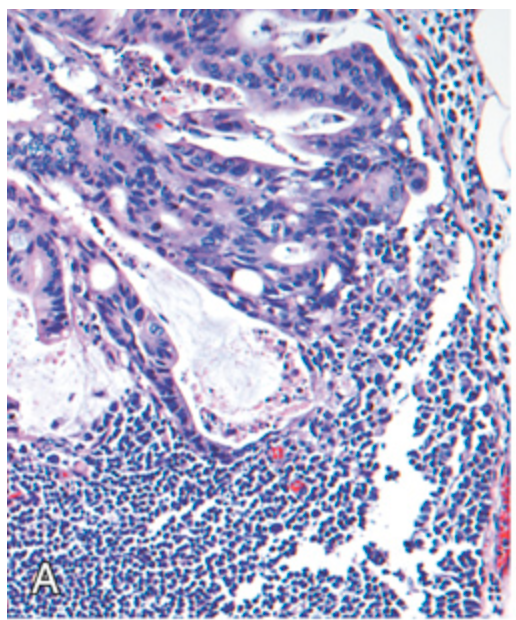

Metastatic colorectal carcinoma. (A) Lymph node metastasis. Note the glandular structures within the subcapsular sinus.

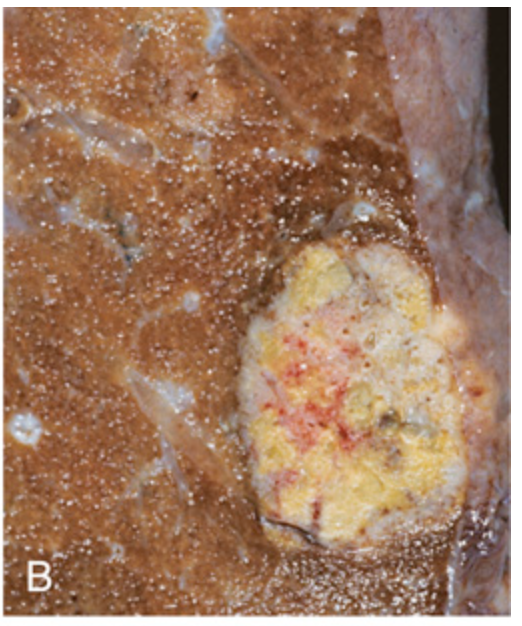

Metastatic colorectal carcinoma. (B) Solitary subpleural nodule of colorectal carcinoma metastatic to the lung.

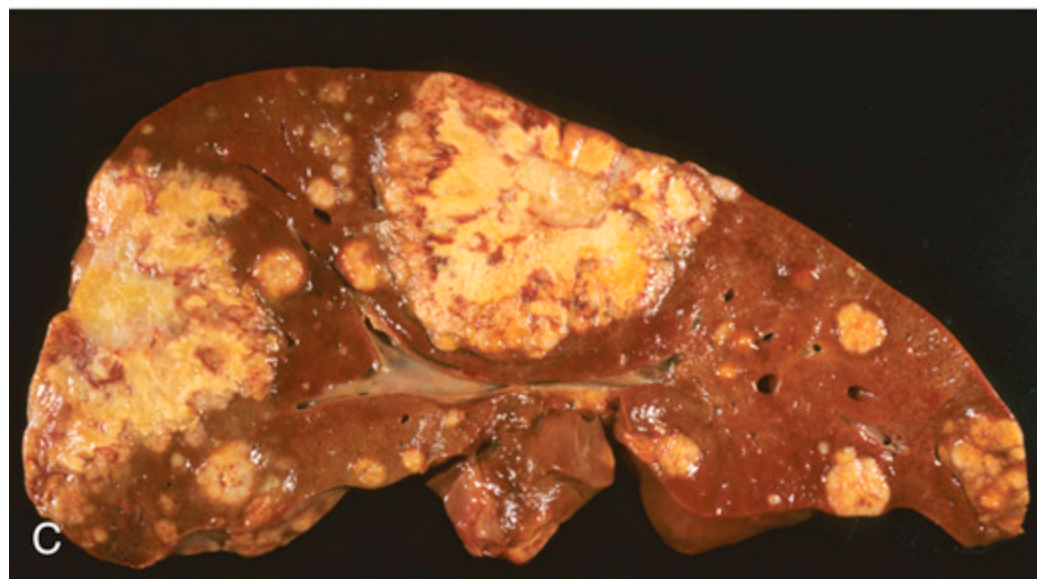

Metastatic colorectal carcinoma. (C) Liver containing two large and many smaller metastases. Note the central necrosis within metastases.