Ch 15 - Hunger and the Future of Food

1/5

Earn XP

Description and Tags

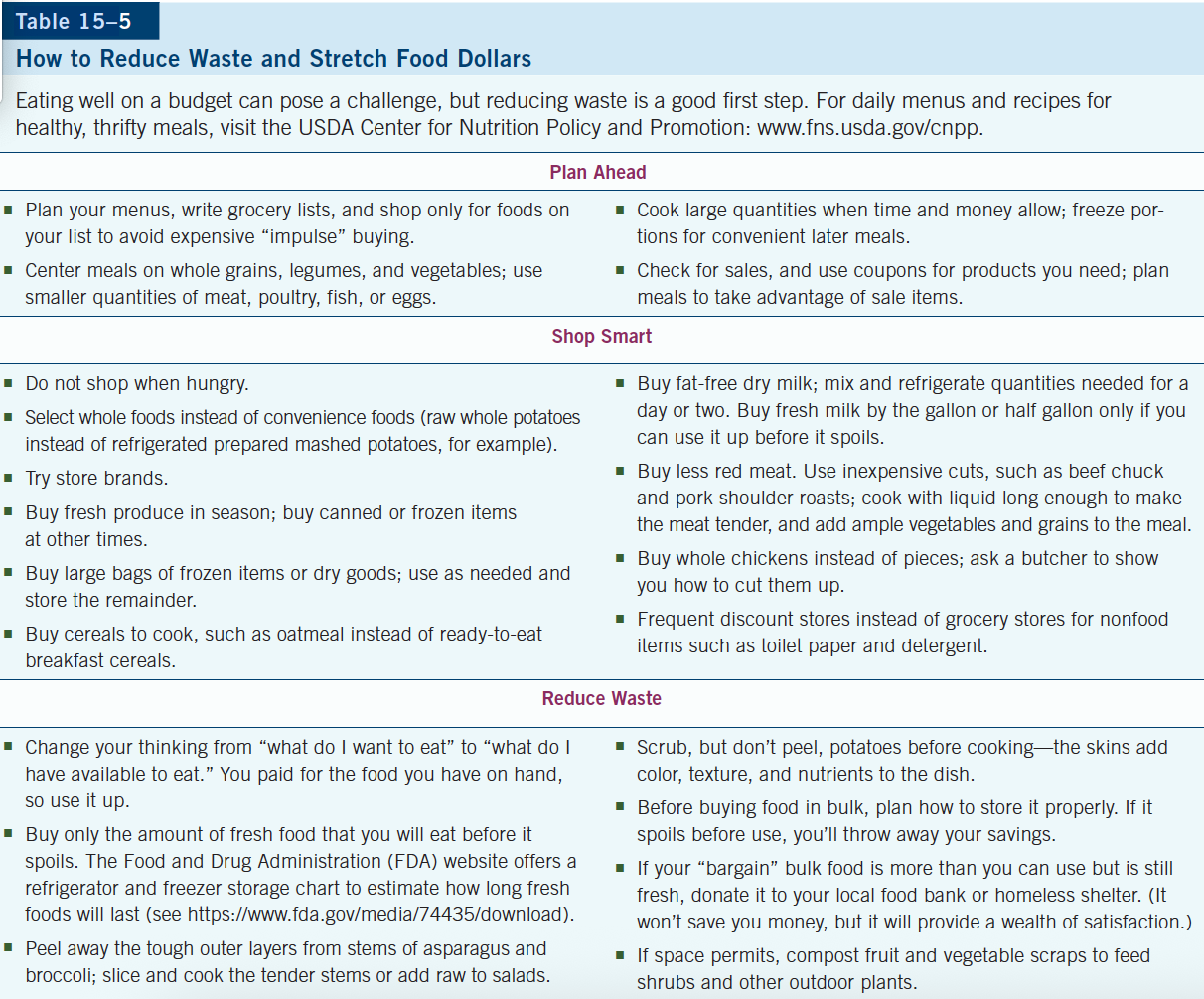

pgs. 568-572, 580-583 Table 15-5 pg. 580

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

6 Terms

World Poverty and Hunger

Famine

The most visible form of hunger is famine, an extreme food crisis in which

multitudes of people in an area starve and die. The natural causes of famine—droughts,

floods, and pests—occur, of course, but they take second place behind political and

social causes. For people of marginal existence, a sudden increase in food prices, a drop

in workers’ incomes, a change in government policy, or outbreak of war can suddenly

leave millions hungry. The World Food Programme of the United Nations responds to

food emergencies around the globe.

Intractable hunger and poverty remain enormous challenges to the world. In parts

of Africa and the Middle East, killer famines recur whenever human conflicts converge

with droughts in countries that have little food in reserve even in a peaceful year.

Racial, ethnic, and religious hatred along with monetary greed often underlie the food

deprivation of whole groups of people. Farmers become warriors and agricultural fields

become battlegrounds while citizens starve. Food becomes a weapon when warring factions

repel international famine relief, or steal it for themselves, in hopes of starving

their opponents before they themselves succumb.

The Malnutrition of Extreme Poverty

In the world’s most impoverished areas, persistent hunger inevitably leads to malnutrition.

Multitudes of adults suffer day to day from the effects of malnutrition, but medical personnel

often fail to properly diagnose these conditions. Most often, adults with malnutrition

feel vaguely ill; they lose fat, muscle, and strength—they are thin and getting thinner.

Their energy and enthusiasm are sapped away. With unrelenting food shortages, observable

nutrient deficiency diseases develop.

Hidden Hunger—Vitamin and Mineral Deficiencies

Almost 2 billion people worldwide who consume sufficient calories still lack the variety

and quality of foods needed to provide sufficient vitamins and minerals—they suffer

the hidden hunger of deficiencies. Nutrient deficiency diseases emerge as body systems

begin to fail. Iron, iodine, vitamin A, and zinc are most commonly lacking, and the

results can be severe—learning disabilities, mental retardation, impaired immunity,

blindness, incapacity to work, and premature death.

These tragedies are devastating not only to individuals but also to entire nations.

When many citizens suffer from mental retardation or blindness, or are incapacitated

from parasites and serious infections, or die early from malnutrition, national economies

decline as productivity ceases and health-care costs soar.

The World Health Organization sets broad goals to ensure access to safe, nutritious,

and sufficient food for all people at all times, and to extinguish all forms of malnutrition.

The COVID-19 pandemic dealt these goals a severe setback. An estimated 100 million

additional people have been thrown into hunger, and many millions of them are

children.

Malnutrition in adults most often appears as general thinness and loss of muscle.

Vitamin and mineral deficiencies cause much misery worldwide.

Consequences of Childhood Malnutrition

In contrast to malnourished adults, young impoverished and malnourished

children often exhibit specific, more readily identifiable conditions. The form

malnutrition takes in a hungry child depends partly on the nature of the food

shortage that caused it. The most perilous condition, severe acute malnutrition (SAM), occurs when food suddenly becomes unavailable, as in drought or war.

Less immediately deadly but still damaging to health is chronic malnutrition,

the unrelenting chronic food deprivation that occurs in areas where food supplies

are chronically scanty and food quality is poor.

SAM

About 10 percent of the world’s children suffer from SAM, often diagnosed

by their degree of wasting. In the form of SAM called marasmus, lean

and fat tissues have wasted away, burned off to provide energy to stay alive.

Children with marasmus weigh too little for their height, and their upper arm

circumferences measure smaller than normal. Loose skin on

the buttocks and thighs often sags down, so that these children look as if they

are wearing baggy pants. They often feel cold and are obviously ill. Sadly, such children

are described as just “skin and bones.”

Some starving children face this threat to life by engaging in as little activity as

possible—not even crying for food. Others cry inconsolably. All of the muscles, including

the heart muscle, are weak and deteriorating. Enzymes are in short supply, and

the GI tract lining deteriorates. Consequently, what little food is eaten often cannot be absorbed.

A less common form of SAM is kwashiorkor. Its distinguishing feature is edema,

a fluid shift out of the blood and into the tissues that causes swelling. Loss of hair color

is also common, and telltale patchy and scaly skin develops, often with sores that fail

to heal. In a dangerous combination condition—marasmic kwashiorkor—muscles

waste, but the wasting may not be apparent because the child’s face, limbs, and abdomen

are swollen with edema. Historically, kwashiorkor was attributed to too little

protein in the diet, but today researchers recognize that the meager diets of starving

children do not differ much—they all lack protein and many other nutrients.

Each year, 3.1 million children, some 6 children every minute, die as a result of poor

nutrition. Most of them do not starve to death—they die from the diarrhea and dehydration

that accompany infections, such as malaria, measles, and pneumonia.

Chronic Malnutrition

A much greater number of children worldwide live with

chronic malnutrition. They subsist on diluted cereal drinks that supply scant energy

and even less protein; such food allows them to survive but not to thrive. Intestinal

parasites drain nourishment away, too. Growth ceases because they chronically lack

the nutrients required to grow normally—they develop stunting, and it can be irreversible.

13 They may appear normal because their bodies are normally proportioned, but these stunted children may be no larger at age 4 than at 2, and they often suffer the

miseries of malnutrition: frequent infections and diarrhea, and vitamin and mineral deficiencies.

Malnutrition in adults is widespread but is often overlooked; severe observable deficiency diseases develop as body systems fail.

Many of the world’s children suffer from wasting due to severe acute malnutrition, the deadliest form of malnutrition.

Many more children’s growth is stunted because they chronically lack the nutrients needed to grow normally.

Medical Nutrition Therapy

Loss of appetite and impaired nutrient absorption interfere with attempts to provide

nourishment to a malnourished child. Even with hospital care, many children do not

recover from SAM—their malnutrition proves fatal. For a chance to restore metabolic

balance and to resume physical growth and mental development, children with

SAM need medication and nursing care for their illnesses, and skillful reintroduction of nutrients from specially formulated fluids and foods.

Children dehydrated from diarrhea need immediate rehydration. With severe fluid and

mineral losses, blood pressure drops and the heartbeat weakens. The right fluid, given

quickly by knowledgeable providers, can help raise the blood pressure and strengthen

the heartbeat, thereby averting death. Health-care workers save millions of lives each

year by reversing dehydration with oral rehydration therapy (ORT). In addition, such

children need adequate sanitation and a safe water supply to prevent infectious diseases.

Once medically stable, malnourished children benefit from ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF), specially formulated food products intended to promote rapid reversal of

weight loss and nutrient deficiencies. Manufacturers blend smooth pastes of oil and

sugars with ground peanuts, powdered milk, or other protein sources and seal premeasured

single doses in sterilized pouches. RUTF are ready to eat: they need not be mixed

with water (a plus in areas with unclean water sources) or prepared in any way, and

the pouches resist bacterial contamination. Importantly, RUTF can be safely stored for 3

to 4 months without refrigeration, a rare luxury in many impoverished areas.

Cost is the downside of commercial RUTF products: they are expensive to buy and

ship to impoverished areas. A child may need to receive daily RUTF for up to 3 months

for a full recovery with a low risk of relapse. To lower the cost, RUTF pastes can often

be made on site from affordable local ingredients, increasing its availability to children suffering from severe malnutrition.

Oral rehydration therapy and ready-to-use therapeutic foods, if properly administered, can save the lives of starving children.

Commercial RUTF products are costly, but similar foods made from local ingredients cost less.

The Future Food Supply and the Environment

Banishing hunger for all of the world’s people poses two major challenges. The first is

to provide enough food to meet the needs of the Earth’s growing population without

destroying the natural resources and conditions needed to continue producing food.

The second challenge is to ensure that all people have access to enough nutritious food to live active, healthy lives.

By all accounts, today’s total world food supply can feed the entire current population.

For future supplies to remain ample, the world must cope with forces that threaten

the production and distribution of its food.

Threats to the Food Supply

Many forces compound to threaten world food production and distribution, both

today and in coming decades.

Populattion growth. Every 60 seconds, 109 people die in the world, but in that

same 60 seconds 255 are born to replace them. Every year, the Earth gains

another 80,000,000 new residents to feed, most born in impoverished areas. By

2050, a billion additional tons of grain will be needed to feed the world’s population,

but such an increase may not be possible if the human population exceeds

the Earth’s carrying capacity.

Loss of food-producing land. Agriculture uses about half of the world’s habitable

land. Food-producing land is becoming saltier, eroding, and being paved over.

The world’s deserts are expanding. As a result, huge natural areas are converted

to food production each year.

Fossil fuel use. The entire food industry, from production and harvest through processing

and delivery, requires 30 percent of all energy used worldwide, contributing

significantly to greenhouse gas emissions. Fossil fuel use underlies much

world economic growth, with associated pollution of air, soil, and water.

Greenhouse gases. More than 25 percent of the world’s greenhouse gases come

directly from food systems. Agricultural sources include livestock methane production,

fossil fuel use, fertilizer manufacture and application, and machinery. Other

sources involve food processing, transport, packaging, and retail operations.

Rapid, widespread, and intensifying global climate change. That climate change is

occurring is no longer a serious academic debate. Strong evidence indicates that

recent warming is largely caused by human activities, especially the release of

greenhouse gases through the burning of fossil fuels.

In every world region, changes to the Earth’s climate appear to be occurring much faster than predicted. Many changes already set into motion are unprecedented, and some, such as sea level rise, are irreversible over centuries or millennia.

Increasing natural disasters. Society’s slow response to heed the warnings of

scientists jeopardizes human life and livelihoods. Bouts of unsurvivable heat

and humidity in some coastal subtropical areas now occur twice as often as

they did in 1980. Everywhere, heat waves, droughts, fires, violent storms, and

floods thwart farmers and destroy crops. Arid deserts are projected to expand by

200 million acres in coming years in sub-Sarahan Africa alone. As ocean heat

builds up, ocean food chains are likely to fail. Starting today, strong and sustained

reductions in emissions of greenhouse gases could quickly limit some of

these effects, but stabilizing global temperatures could take decades.

Species extinctions. Agricultural practices are responsible for 80 percent of extinction

threats. Extinctions of species are occurring at an unprecedented and accelerating

rate, including extinctions of soil microbes, amphibians, birds, mammals, sea life,

plants, and pollinators on which food supplies depend. Of an estimated 14,000

potential edible plants, only 150 to 200 are cultivated, leaving the remaining wild

species at risk. Wild species may hold keys to climate change resiliency. A drought-resistant

wild corn, for example, may contain genes needed to confer drought tolerance

on domestic corn. Loss of wild species threatens global food security.

Fresh water shortages. Agriculture uses 70 percent of the world’s fresh water. Irrigation

and rain wash fertilizers into waterways, polluting them and feeding algae overgrowth

in lakes and oceans, causing dead zones that kill fish and other marine life.

Over 2 billion people live in countries experiencing high water stress, particularly in the Middle East and Africa. If climate change and population growth continue on their current course, water supplies in arid and semi-arid places will dry up, forcing tens of millions of people from their homelands in just a decade or two.

Flooding and wildfires. Crop-damaging localized heavy

storms are becoming more frequent and severe, causing

flash floods that erode vast acreages of topsoil from

parched land. As the climate warms and areas become

drier, wildfires burn hotter and sweep through millions

of acres of formerly lush forests.

Ocean pollution, warming, and acidification. Ocean pollution

of many kinds is killing fish in large “dead zones” that

expand as excessive algal growth and decay deplete dissolved

oxygen in the water. Ocean water acidity increases

as it dissolves excess carbon dioxide from fossil fuel

emissions, threatening the acid-base balance and other

environmental conditions critical to sea life.

The global problems just described are all related, and, often,

so are their solutions. To think positively, this means that any

initiative people take to address one problem will help solve

many others. To create sustainable, resilient food systems will require that everyone

play a role, starting today. An obvious first step is to stop wasting the food already available.

Current food production and distribution methods are damaging the environmental systems and animal and plant species on which future food production depends.

Future food security is currently threatened by many forces.

Table 15–5: How to Reduce Waste and Stretch Food Dollars

Controversy 15: How Can We Feed Ourselves Sustainably?

If predictions hold true, farmers will soon

face greater pressures to feed a burgeoning

world population while arable

lands on which to do so are diminishing.

To produce this food will require

more land, water, and energy, and it

must be accomplished while conserving

the natural resources that make

growing crops and animals possible into

the future. What is needed is nothing

short of another green revolution, except

that this one must be doubly green:

increasing the productivity of available

land while protecting or restoring the

environment. In addition, people today

are urged to cut food waste and adopt

a sustainable diet, to help ensure that

resources are conserved as people are fed.

The Costs of Current Food Production Methods

Producing food costs the Earth dearly.

The environmental impacts of agriculture

and the food industry take many

forms, including water use and pollution,

greenhouse gas emissions, and resource

overuse. Related concerns of pressing

importance but that exceed the scope of

this discussion include the human costs

of food production, such as child labor,

exposure of farm workers to pesticides,

unfair farm labor policies, and other

social justice issues associated with

agriculture both domestically and around the world.

Soil and Water Depletion

Earth’s soil and fresh water are being

depleted by today’s agricultural practices.

Indiscriminate land clearing

(deforestation) and overuse by cattle

(overgrazing) are major causes. Traditional

farming methods that turn over all topsoil each season expose vast areas

to the erosive forces of wind and water.

Exposed topsoil blows away on the wind or washes into the sea with rain, leaving unfertile areas

behind. Moisture rapidly evaporates from

exposed soil, drying it, necessitating

more frequent water applications.

Such unsustainable agriculture has

already destroyed many once-fertile

regions where civilizations formerly flourished.

The dry, salty deserts of North

Africa were once rich soils, the plowed

and irrigated wheat fields that fed the

mighty Roman Empire. Today, the

Earth’s remaining rich soil areas are suffering

the same mistreatment, causing

destruction on an unprecedented scale.

Hidden Costs of Food Production

Clearly, food imposes an additional cost

on the environment—a constellation of

inputs not simple to grasp by consumers

in the grocery store and not reflected in

the price tags. For example, to produce

300 calories of canned corn, more

than 6,000 calories of fuel are used to

produce both corn and can, and then

transport it. These other “hidden” costs

must be accounted for, so that our food

systems can adapt to changing conditions

with workable plans to feed future

populations.

Defining a Sustainable Diet

Not all diets are equally taxing on the

environment, and people today can

choose to eat a more sustainable diet.

A sustainable diet significantly reduces

the environmental costs of producing

food. Such a diet is higher than the typical

U.S. diet in legumes, whole grains,

nuts, seeds, fruit, and vegetables and

lower in red meats and highly processed

foods. Perhaps the greatest reason

to choose a sustainable diet is self-interest—

its foods are highly nutritious

and, with regular consumption, it can

reduce the risks of chronic diseases.

Sustainable diets can be diverse in

their cultural characteristics, but they all

have these things in common. Sustainable diets:

1. Ensure optimal human nutrition and support health at every life stage.

2. Protect the natural environment and biodiversity.

3. Achieve fairness in the economics of food production and purchase.

4. Reflect societal and cultural values and protect animal welfare.

These four domains often collide

in ways that pose difficulties

for decision-makers, particularly

when considering individual

foods. For example, sugar from

beets provides food energy

cheaply and supports farm and

labor incomes. Processing beet

sugar uses little water and emits

minimal greenhouse gases.

However, sugar fails to meet the

primary sustainable criterion—

sugar is low in nutrients, and

high sugar intakes are linked

with dental caries, suboptimal

nutrient intakes, and metabolic

diseases. Conversely, fresh

fruit and vegetables meet

the human health criterion

superbly, but growing, processing,

and delivering them have

greater environmental and

monetary costs than does beet

sugar. In addition, growers

and harvesters of fruits and

vegetables may work in unfair conditions, problems that must be remedied

to meet sustainability criteria.

The Burden of Livestock

Cattle, buffalo, and sheep are ruminants,

animals with specialized stomachs that

allow them to ferment and absorb energy

from fibrous plants, such as grasses, hay,

beet fiber (a byproduct of sugar beet processing),

and other roughage that people

cannot consume directly. The animals

convert these fibrous materials into valuable

protein that people can eat, digest,

and use to build and maintain body tissues

and support critical body functions.

Raising livestock, and particularly

cattle, in wealthy, food-rich nations takes

an enormous toll on land and energy

resources. Cattle herds occupy land

that once maintained itself in a richly

biodiverse natural state. As too many

of the same kinds of animals overgraze

and trample the same land continuously,

it suffers species loss, soil erosion, and

water depletion. Livestock use more than

75 percent of agricultural land but produce

less than 20 percent of the world’s

calories and less than 40 percent of the

world’s protein that people require.

U.S. Meat Production

When animals are raised in concentrated

areas such as cattle feedlots or giant

hog or chicken ”farms,” huge masses

of manure are produced in these overcrowded,

factory-style farms. These

masses of manure emit potent greenhouse

gases into the air as they decay and, with

rain, they leach into local soils and water

supplies, polluting them. In addition, fermentation

of fibers in the ruminant digestive

tract produces methane gas (a highly

potent greenhouse gas) as a byproduct.

The methane is released into the air,

mostly from the animals’ mouths.

Food animals themselves must be

fed, and grain and soy are grown for them

on other land. This often necessitates

plowing fields and applying fertilizers,

herbicides, pesticides, and irrigation.

Fertilizers emit nitrous oxide, a greenhouse

gas with 265 times the global

warming potential of carbon dioxide. In

all, almost 15 percent of yearly global

greenhouse gas emissions derive from

livestock production.

Some Benefits of Livestock in the Developing World

In food-stressed areas of the world,

where nutrients are in short supply, the

benefits of ruminant animals appear to

outweigh their environmental costs, at

least temporarily. Ruminants help provide

needed nourishment to marginally

fed women and children, help stabilize

local economies, provide income

streams to families, and contribute to

regional food security. Food animals

raised in these areas graze on sparse

wild grasses or shrubs that grow mostly

on lands unsuitable to other uses, thus

converting inedible plants into milk

and meat that can be consumed, sold,

or traded. To find enough food, these

animals must continually travel to new

grazing areas, allowing previously grazed

areas time to regenerate and grow.

At some point in an area’s economic

development, incomes rise and so does

consumer demand for meat and dairy

products, putting greater pressure on

ecological systems. In 1999, meat and

milk consumption in East Asia was

about 100 pounds per person per year;

by 2030, yearly consumption will have

risen to almost 170 pounds per person.

This unsustainable global trend poses a

growing threat, particularly when cattle

are raised in unsustainable ways. The

sheer number of cattle currently on

Earth, almost 1 billion, creates a serious

environmental impact that is worsening

with growing numbers of herds.

Advances in Agroecology

Should plants replace all livestock in U.S.

agriculture, then? Would this shift cause

nutrient inadequacies in the U.S. diet?

Would it achieve sustainability? Answers

to these and other pressing questions are

emerging from studies in agroecology,

the field of science focused on the needs

of agriculture and the environment.

The Carbon Sink Concept

Unlike animals, living plants act as a

carbon sink, a sort of carbon storage

unit. Green plants growing on land or

in oceans capture and remove carbon

dioxide from the air. The soil itself, left undisturbed, also indirectly sequesters

carbon from atmospheric carbon

dioxide. Using photosynthesis, plants

incorporate carbon atoms in the carbohydrates

that form their tissues

and structures. Plant roots also

release carbon into the soil where it nourishes

microbes that form part of a vast,

biodiverse community of organisms that

enrich the soil, making it more hospitable

to growing plants—a beneficial cycle.

Carbon sinks remain intact until

some force acts to release their carbon,

such as farm tilling that exposes the

soil to the air and eliminates plant

roots, or applying pesticides that

destroy the soil’s microbial and animal

communities. A principle of agroecology,

called “no-till” farming, protects the

carbon sink of soils by keeping the soil

covered with plants as much as possible

and disturbing root systems as little as

possible during planting and harvesting

of foods. The pesticide-free methods

of organic farming and composting

also improve soil integrity and foster its

carbon sink function by protecting and

feeding its living inhabitants.

The Future of Livestock

The problem with cattle may not be the

cows themselves as much as the unsustainable

techniques used to raise them. In

fact, herds can be part of at least one solution.

When farmers plant cover crops to

let their fields rest, cattle herds can graze

those fields, providing extra income for the

farmers while keeping the fields trimmed

and the soil in good condition for the next

year’s crops. Rotating herds among various

pastures and fields reduces damage,

adds nutrients from manure, and allows

forage plants to recover and diversify.

Another way to minimize ecological impact

of livestock is to capture the gases released

from cattle, hog, and poultry manure

before the gasses enter the atmosphere

and the manure runs off into water. The

recovered gases can be used as an energy

source for electricity, heating, or transportation

fuel on the farm. Safely composted

manure makes excellent fertilizer.

In truth, changing farming methods

on a global scale will take more

than scientific discovery. It will require large-scale commitment to adopting new

practices, along with strong professional

group and government support. So

far, progress has been too slow to

ensure a sustainable future for our

food supply.

Sustainable Protein Choices

Despite advances in agroecology, today’s

animal protein foods are far more taxing

than plant-based proteins on ecological

resources and systems. Replacing

just one meal of animal protein with

plant protein each day can significantly

reduce greenhouse emissions and water

consumption, while improving diet

quality for most people.

Legumes

Producing a meal of beef emits 60 times

more greenhouse gas than does producing

a nutritionally similar meal of

legumes. Legumes enrich soil, too,

because they capture nitrogen from the

atmosphere and transfer it to nodules

on their roots and ultimately to the soil. When

farmers alternate their cash crops with

deep-rooted legumes, the legume plants

remove nitrogen and carbon dioxide from

the atmosphere, and drive these elements

deep into the soil where they stay sequestered

until they are taken up and used by

the next season’s cash crops.

Nuts

Nuts provide valuable protein with little

or no environmental impact. Groves of nut

trees absorb carbon dioxide to build

their massive roots, trunks, leaves, nuts,

and other structures—they are carbon

sinks. With the exception of water for

trees grown in arid zones, nuts require

few inputs, and after initial planting, they

bear crops for decades with no soil disturbance.

As with all foods, inputs are

required for harvesting, processing, and

transporting the nuts to market.

Fish and Seafood

Choosing fish and seafood in place of

some meat is sensible, too, because

fish convert feed to edible protein with

relative efficiency. However, some species are overfished and in danger of

collapse, while some others are raised or

harvested unsustainably. Much of the

world’s fish and seafood today is supplied

by aquaculture, fish farms stocked

with edible species raised in ocean

cages or inland pools and fed with fishmeal.

Fish meal is often made from wild

fish captures, further depleting wild fish

stocks, also an unsustainable practice.

Buying sustainable seafood can be

tricky; strategies change as fisheries

adapt and stocks recover.

Meat Alternatives

For meat-loving but concerned consumers,

plant-based meat alternatives that

mimic the taste and texture of burgers or

chicken may ease the transition from a

meat-centered dietary pattern to a plantbased

diet. The manufactures claim

that, compared with beef, their products

require less energy, water, and land, and

generate fewer greenhouse gas emissions.

Some questions remain about the

role of these highly processed foods as

part of a healthy and sustainable diet.

Good for You, Good for the Planet

Conscientious consumers are making

a difference through the choices they

make, and are sending clear signals to

growers and manufacturers that they

demand more sustainable products.

New, fresh ways of thinking about how

to obtain foods can also enliven the diet

and enrich daily life.

Keeping Local Profits Local

Farmers selling their broccoli, carrots,

and apples at city farmers markets and

roadside stands often net a higher profit

than when selling to wholesalers. Buying

local supports farm fairness, too. Farm

workers in food-insecure countries earn

meager wages to grow and harvest foods

shipped to wealthy nations. This keeps

food prices low for wealthy consumers

but traps the farm workers in inescapable poverty.

The answer is not simply to “buy

local.” Shopping for local foods makes

sense for local economies, but what

consumers buy rather than where

may make the greatest environmental

impact. A meal of locally grown beef or

chicken has a larger ecological cost than

legumes or vegetables grown elsewhere

and shipped. If “elsewhere” is an area

known to pay fair farm wages, this

choice supports social justice as well.

Buying in Season

Buying local in-season foods provides

several other benefits. Off-season produce,

fresh or frozen, must be refrigerated

and transported often thousands

of miles by jet planes, freighter ships,

freight trains, or semitrucks, greatly

increasing its ecological impact. In addition,

families who buy homegrown produce

or grow it themselves tend to eat

greater quantities and varieties of fruit

and vegetables, and the health benefits

of this practice are well known. Alternatively,

through a farm share, consumers

can buy weekly shares of a local farmer’s

fresh harvest in season.

Conclusion

The problems of providing food for future

generations are global in scope, yet the

actions of individual people lie at the

heart of their solutions.

Do what you can to tread lightly on

the Earth. Advocate for sustainability

and agricultural fairness, and vote with

your food purchases. Celebrate changes

that are possible today by making them

permanent and reap the benefits of

increased health, and the promise of

sustainability for future generations. Do

the same with changes that become possible

tomorrow and every day thereafter.

Key Terms

Hunger

physical discomfort, illness, weakness, or pain beyond a mild uneasy sensation arising from a prolonged involuntary lack of food; a consequence of food insecurity.

Food Crisis

a steep decline in food availability with a proportional rise in hunger and malnutrition at the local, national, or global level.

Food Poverty

hunger occurring when enough food exists in an area but some of the people cannot obtain it because they lack money, are being deprived for political reasons, live in a country at war, or suffer from other problems such as underemployment, unemployment, or lack of transportation.

Food Recovery

collecting wholesome surplus food for distribution to people who lack food.

Food Banks

facilities that collect and distribute food donations to authorized organizations feeding the hungry.

Food Pantries

community food collection programs that provide groceries to be prepared and eaten at home.

Emergency Kitchens

programs that provide prepared meals to those who need them. Mobile emergency kitchens can be dispatched to wherever the need is greatest; permanent facilities are often called soup kitchens or congregate meal sites.