Plant microbiome below ground

1/31

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

32 Terms

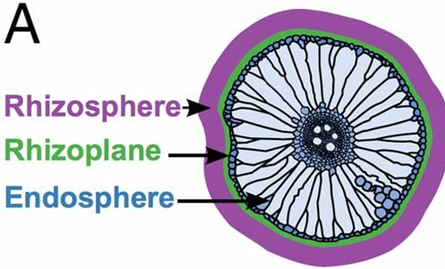

Root microbiome

3 main compartments

Rhizosphere – the soil tightly attached to the roots

Rhizoplane – microbes physically attached to the surface of the root

Endosphere – all the microbes that live in the internal compartments (within and between cells)

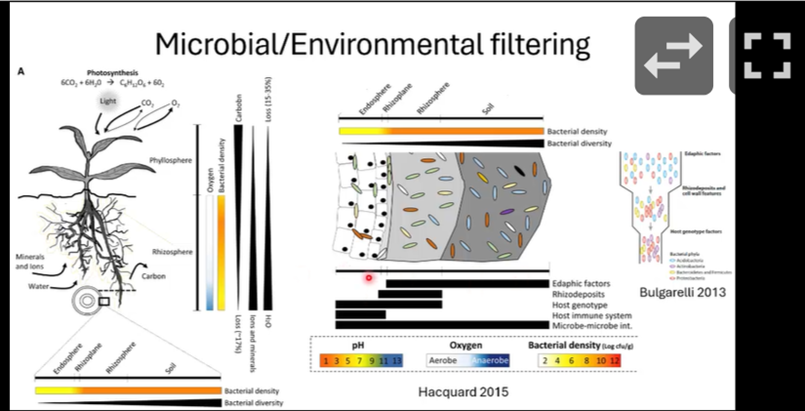

Microbial filtering

Plant will select subsets of microbes which survive in its environment

Factors that control the structure of the microbiome include:

edaphic factors (soil factors like pH)

rhizodeposits

host genome

host immune system

microbe-microbe interactions.

These factors have varying degrees of importance from the rhizophere through to the endosphere

Soil microbiome very diverse, only a small portion can survive in the rhizosphere, of those only a small portion can colonise the plant roots etc. With each level closer to the plant, you get increased selectivity of microorgansims

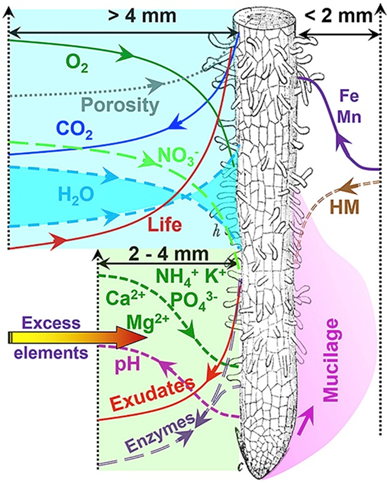

The rhizosphere

Hotspot of microbial activity

Includes soil 2mm from the root surface

Interface between the plant and the environment – lots of nutrient transfer

Some plants can release up to 40% of their photosynthetic carbon into this space

Plants are able to alter their rhizosphere depending on who they want to colonise their roots or what they need

Difficult to define as its made up of lots of gradients, which makes it difficult to standardise across studies

E,g: as you move closer to the roots, you change oxygen concentration, the influence of different exudates present etc.

components of the rhizosphere: rhizodeposits

Term which includes anything a plant does to alter its rhizosphere

Includes:

Sloughed off root cap and border cells – acts as a lubricant to help cells move through

Mucilage

Exudates – carbons pumped out to feed microbes

Enzymes – pick up plants own nutrients

Other forms of carbon exchange:

Volatiles – released when plants are attacked and used to signal to other plants that there are predators nearby

Symbioses

Cell death – carbon sequestered into soil

rhizodeposits: carbon excahnges

Carbon exchanges

Typically categorised in 2 broad groups of ways of releasing carbon

Active

Usually secretions

High Mw

Passive

Usually occurs via diffusion (can be passive or facilitated)

Low molecular weight

Rhizodeposits: Exudates

Exudates are typically categorised into high molecular weight like mucilage and low Mw like the rest of them.

High molecular weight exudates - mucilage

High molecular weight and active secretion

Functions:

Lubrication for a growing root

Reduces dessication

Soil aggregation – alters water and oxygen dynamics

Can help keep moisture gradient in drought

Certain types of roots house nitrogen fixers

Can help with microbial defence – traps pathogens

Low molecular weight exudates

Hundreds of low Mw carbon compounds

High diversity

Chemical fingerprint of the plant – use it figure out the species, lifestage, stress state etc.

Generally grouped into organic acids, amino acids, proteins, sugars and phenolics (free and bound to lignins)

Exudate function:

Nutrient acquisition

Antagonism/allelopathy – carbon compound that is toxic for other organisms

Microbial attraction

Allows for resource partitioning

Each plant has a chemical fingerprint, things that influence this includes:

Breeding

Plant genotype

Theories on why exudates exist: could be excess carbon but most likely has a role in shaping the symbioses

Physiological role of exudates

Exudates as a defence – some of the physiological roles of exudates

Mucilage – physically traps pathogens

Phytoalexins – compounds that plants release in response to infection

Phytoanticipins – compounds that plants release all the time that act as antimicrobial peptides, such as benzoxanoids (nitrogen containing compounds)

Phenolics – including flavonoids and phenylpropanoids

Terpenoids

Microbial attraction – chemotaxis

Exudates allows for chemotaxis to occur – recruitment of microorganisms through chemical gradients

Bacteria localise to the root tips where the most exudates are

Exudates: phenolics

Phenolics are antimicrobial but specialised slow growing microbes consume these phenolics – these microbes called oligotrophic

Some phenolics, such as caffeic acid, are very inhibitory – each phenolic has a different role

Some of them can cause an increase in respiration in microbes, some of them cause a decrease in respiration in microbes

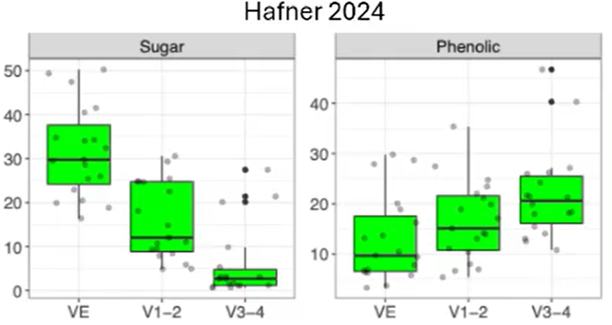

Example of changes in exudate profile

Correlation between sugars and phenolics

In the emergent stage the root is flooded with sugars but as it grows, levels of sugars decrease as instead of forming the rhizosphere the plant is focused on maintaining the rhizosphere

how do we study exudates

In the lab

Put plant roots in a hydroponic solution and they release their exudates

Can analyse these using mass spec, liquid chromatography

In the field

Dig up the root of tress and place them in syringes containing solution

Can now analyse solution using same techniques

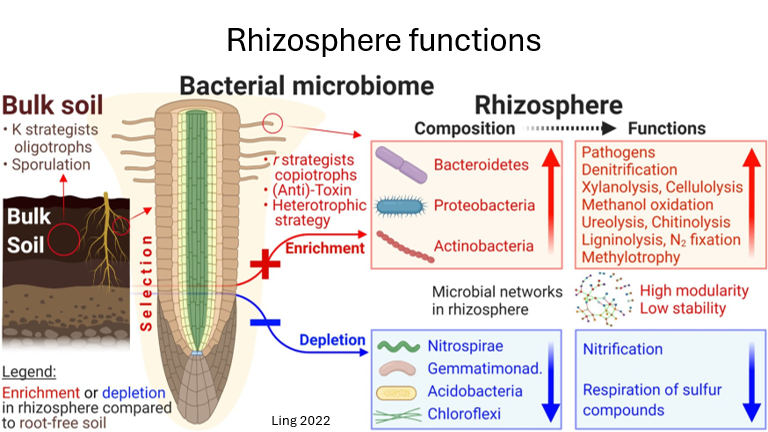

function of the rhizosphere

Physically structures the abiotic environment which alters the biotic environment.

See a different chemical profile depending on the life stage of the plant – this environment that the plant generates controls which bacteria can survive – how they shape the rhizosphere.

Typical rhizosphere composition

Microbes enriched: r strategists which are copiotrophs (fast growing organisms with high turnover rate.

depleted microbes: nitrogen fixing bacteria

enriched bacteria:

Bacteroidetes

actinobacteria

proteobacteria

depleted bacteria

nitrospira

acidobacteria

chloroflexi

Common functions:

denitrification

nitrogen fixation

urolysis

chitinolysis

decreased functions:

nitrification

respiration of sulphur compounds

the rhizoplane

Tightly attached microbes to the surface of the root itself

Selective as microbes have to be able to survive and colonise the root morphology —> limitation of space forces microbes to compete

Now we have difficulties occurring with the plant immune system and the presence of:

PRRS

PAMPs

Flagellin proteins – lots of bacteria have flagella but not all flagellin proteins will set off the plants immune system, quite a high degree of sensitivity

root endosphere

Internal environment of the root itself, made up of endophytes

Problems associated with the plant immune system

Contamination makes it difficult to study – usually when you want to study the endosphere crush up the root and do 16SRNA amplification using PCR to identify colonisers. But chloroplasts and mitochondria also carry 16SRNA genes which contaminate your sample

Internal microbes

Can colonise intercellular and intracellular spaces

Require specialised genes

Usually have an enrichment of polymer-degrading enzymes (cellulases and pectinases for example)

Also often have secretion systems

Plant associated taxa in the endosphere

Lots of commensals

Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) – umbrella term for microbes that help the host grow

Mycorrhizal fungi

Pathogens

plant-microbiome interactions

Microbiomes have a lot of control around plant health physiology, can:

Alter root structure

Alter plant immune responses

Impact plant nutrition

Reduce abiotic stress

Alter plat nutrient status

Examples:

Auxin (indole 3 acetic acid) – microbes produce or degrade auxin to influence growth pathways

Jasmonic acid and salycilic acid – growth hormones important for tsress signalling and immunity. Microbes can inhibit the production or produce more of it.

Ethylene – important for stress responses in drought. ACC oxidase or ACC deaminase can increase or decrease ethylene levels.

Giberellins – growth hormones which can be produced by some microbes

Nutrient availability of phosphorous, nitrogen, potassium and iron

Specific example: example of pseudomonas syringae manipulating signaling

Produces phytotoxin coronatine (mimics jasmonic acid) which supresses siacylic acid defence signalling

By manipulating salicylic acid pathway means that it can manipulate the host immune system to be less effective

Does this by stiulating auxin production and using a T3SS promotes lateral root formation, which allows the bacteria to invade more easily.

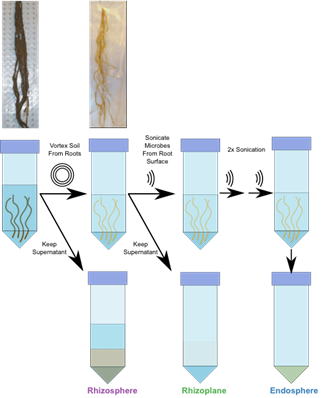

collecting the microbiome

To extract the rhizosphere – dig up the roots, shake the roots and vortex the solution

Rhizoplane – requires sonication of the clean roots which helps the helps the bacteria attached to the roots detach

Root endosphere – use the whole sonicated, cleaned root and crush it up to extract the DNA. Can then vortex this to create a pellet

plant symbioses

Not just one interaction, involves 3 different types of interaction:

Mutualism – both organisms behefit

Commensalism – one benefits, the other is unaffected

Parasitism – one organism benefits, the other is negatively affected

most common plant mututalisms are

mycorrhizal fungi

legume forming bacteria

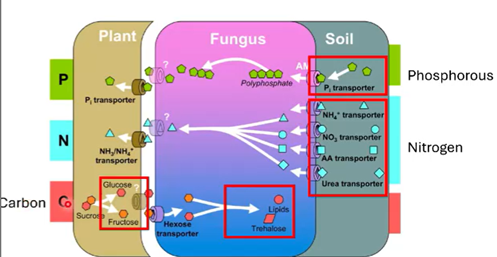

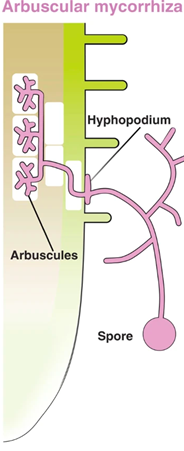

mycorrhizal fungi

Invade and create arbuscules inside the plant which allows for nutrient exchange

Mutualistic relationship with plants

Extension of the root system – allow a greater SA to reach nutrients

Exchange P and N for carbon

Can improve plant stress tolerance as well as water access

99% of all plants form this relationship – plants that don’t do this are abnormal

Evolved around 400-500mya

Vital for this territorialisation of plants

4-20% of the photosynthetic carbon is transferred to the fungus in the form of sugars and lipids, in exchange the fungi exchange phosphorus and nitrogen

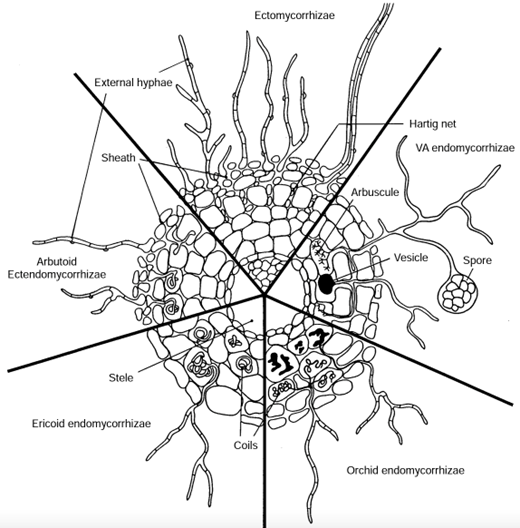

mycorrhizal groups

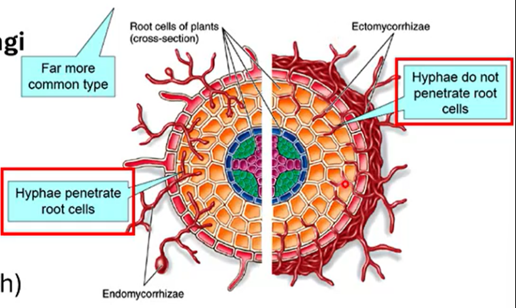

Endomycorhhizal fungi

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi

Ericoidmycorrhizal fungi

Orchid mycorrhizal fungi

Ectomycorrhizal fungi

Ectendomycorhizal fungi

Arbutoid mycorrhizal fungi

Endomycorhhizal fungi

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi

Ericoidmycorrhizal fungi

Orchid mycorrhizal fungi

Key interaction structures are arbuscules inside the cells of the roots

80% of plants have this type of fungi

Vital for territorialisation alongside other fungi, mucoromycota

Obligate – fungus cannot get carbon from anywhere else – requires carbon from the pant

Invade the cell but plant cell wraps a membrane around the arbuscules so they don’t enter the cytosplasm

Endomycorhhizal fungi

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi

Ericoidmycorrhizal fungi

Orchid mycorrhizal fungi

Primarily ascomycota and some basidiomycota

Associated with Ericaceae species (blueberries)

Acidic and infertile soils

Produce coils inside of the cells

Some of them can also form ectomycorrhizal associations

Can still pick up carbon themselves due to degradation genes

obligate interaction

Endomycorhhizal fungi

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi

Ericoidmycorrhizal fungi

Orchid mycorrhizal fungi

Primarily restricted to the Basidiomycota (specifically Agaricomyces)

Associated with orchids – orchids are partially mycoheterotrophic which means that it relies on the fungus to feed it in certain parts of its lifecycle. For an orchid seed to germinate it must associate with this fungi.

Produce coils as their interaction structure

Retain more degradation genes than ectomycorrhizal fungi

coils

are the interaction structures for ericoid and orchid mycorrhizal fungi

Orchid seeds may absorb carbon from hyphae, forming coils inside the cell

Coils are degrade and release the nutrients into the host

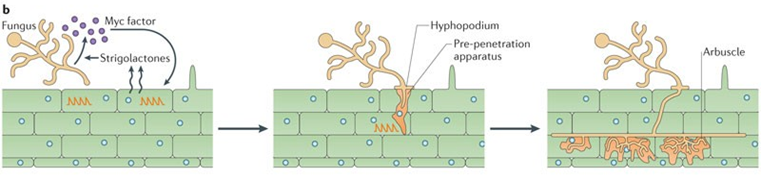

stimulating this interaction

When plants are phosphorous starved, they produce strigalactones

Fungal spores sense the striga lactones using lipochitooligosaccaride mycorrhizal factor (Myc factor) which cause them to germinate and colonise the host

Causes this calcium spike known as common symbiosis pathway

Fungus invade into the root and cause the production of arbuscules

So obligate that the fungi don’t even produce its own lipids for growth (E.g: beta monoacylglycerol is a lipid required for fungal growth but can’t be produced by the fungi)

Ectomycorrizal fungi

Not restricted to one taxonomic group, can be ascomycota or basidiomycota

Does not penetrate into the cell itself – intercellularly

Particularly associate with temperate trees due to nitrogen acquisition – as plants move further north theres less of a phosporous depletion and more depleted in nitrogen

Key features are mantle and Hartig net

Mantle is a fungus layer covering the entire surface of the root. Exudates and water have to pass through this mantle

Hartig net is the fungus that forms between cells

Still have the genes and the enzymes to degrade soil organic matter so are not obligate

Can produce fruiting bodies – mushrooms

Ectendomycotizal fungi: Arbutoid

Basidiomycota

Associate with a subset of plant species within the Ericaceae species

Form this mantle but can also go inside the cells (aspects of both)

Other groups: Monotropoid

Basidiomycota

Also associate with the Ericaceae

Associate with plants without chlorophyll

Key characteristics include the Hartig net and fungal peg

No penetration into the cytoplasm

Mycoheterotrophy – as these plants don’t photosynthesise, they acquire carbon from the fungi

comparing interaction structures

root traits and mycorrhizal fungi

Nice relationship between root traits and microbiome associations

Roots that are thicker, tend to be associated with more mycorrhizal fungi

Other trees make really thin roots which are less reliant on the mycorrizal fungi due to the increased surface area – also means that they’re less invested in their symbiotic partner

Some tree species tend to invest more into a partner, some tend to be more independent

plant parasitism

Mycoheterotrophy

fungi which obtain nutrition from other plants (e.g: achlorophyllous fungi)

Striga

Parasitic plant which responds to striga lactones and colonises it and takes the carbon

Could consider mycorrhizal fungi in some instances to be parasites

Where you have a less co-operative fungal partner, costs more carbon to get the nutrients

Not parasitism in the classical sense because one of the partners not being harmed

Important when we use these fungi to stimulate growth as we want to use the fungal partner which will be the most co-operative

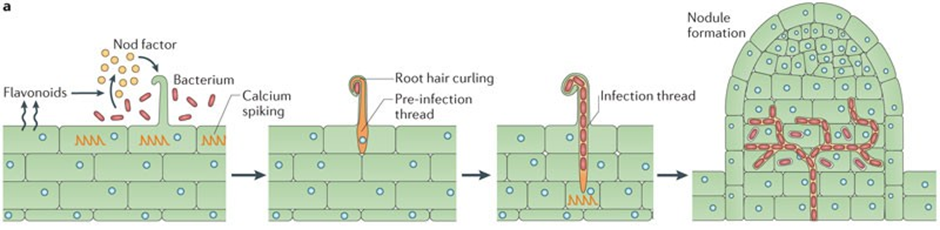

root nodule symbiosis (legume forming bacteria)

Nitrogen fixing root nodule symbiosis (rhizobia)

Paraphyletic: alphaproteobacteria and betaproteobacteria

Ancient relationship

Nodules vital for nitrogen acquisition

Rhizobia fixes nitrogen and sends it back in exchange for carbon and safety.

stimulating the rhizobial partenership

Stimulated by flavonoids

Lipochitooligosaccharides (Nod factors) are released and recognised by Nod factor receptor 1 (NFR1) and NFR5

Common symbiosis pathway causes calcium spikes

Rhizobium associated with a speciifc area of the root hair and Nod signalling causes localised calcium spiking. This causes the growth area to curl towards the attached bacteria.

These continuously repeated, localized shifts in growth direction—driven by the shifting calcium gradient—cause the root hair to grow around the bacterial colony, eventually leading to the formation of a tight curl that entraps the bacteria

This mechanism is also what allows the plant to form a structure called an infection thread which facilitates the entry of the nitrogen fixing bacteria into the root

ecosystem services - the bigger picture of plant symbioses

Forests that are full of arbuscular-associated plants produce higher quality litter

More nitrogen in litter

Breaks down faster

Results in overall changed ecosystem function in the forest

Form and quality of the exudates in the rhizosphere imacts global carbon budgets

Mycorrizal fungi can pull carbon from multiple plants at one time (proved by radiolabelled isotopes)

Applied potential

Use microorganisms to change the nutrient cycling dynamic of that environment

Phosphorous is a limiting nutrient

So much phosphorous is fixed or washed away from the soil and so only a small portion of it is available to the plant host

We can leverage microbial activity to make phosphorous more bioavailable

Can use ectomycorrhizal fungi to understand which tree species will thrive when trying to restore certain forest areas.