SET 5 - Anxiety and Anxiety-Related Disorders

1/26

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

27 Terms

What is the difference between fear and anxiety reactions, and at what point do these become pathological?

Anxiety is a future-oriented state characterized by negative affect in which a person focuses on the possibility of uncontrollable danger or misfortune; in contrast, fear is a present-oriented state characterized by strong escapist tendencies and a surge in the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system in response to current danger. Fear and anxiety are very normal emotions, but they become pathological when the reaction is out of proportion to the situation (anxiety) or occurs without a real threat (panic).

What are the three differentiating factors that distinguish adaptive from disordered anxiety?

Intensity: Is the level of anxiety higher than what peers typically experience in the same situation?

Duration: Has the anxiety lasted for six months or longer?

Impact on Functioning: Is the anxiety helping the person, or is it interfering with daily functioning?

Why is anxiety difficult to study?

Anxiety is difficult to study because it shows up in different ways for different people. It can appear as observable behaviours like nail-biting or fidgeting, physiological symptoms like muscle tension or a racing heart, or as self-reported feelings of unease / discomfort.

What happens when the alarm response of fear occurs in the absence of real danger?

This results in a panic attack, which is a sudden and intense surge of fear or discomfort that occurs without an actual threat or danger. There are two types of panic attacks: (1) expected, which occur in response to a known trigger and are common in specific phobias and social anxiety disorder, and (2) unexpected, which occur without warning and are characteristic of panic disorder.

What are the major etiological factors implicated in anxiety disorders?

Biological Factors

Genes don’t cause anxiety directly but increase vulnerability under certain environmental conditions.

Low GABA levels and dysregulation in the noradrenergic and serotonergic systems.

Overactivation of the behavioural inhibition system (threat detection) and the fight-or-flight system (threat response).

Psychological Factors

The alarm response (fear) is learned through classical conditioning and reinforced through operant conditioning.

Start with a dangerous situation in the environment (true alarm). This becomes associated with environmental cues through classical conditioning. Later, those same cues can trigger the alarm response even when no real danger is present (learned alarm). This learned alarm is reinforced through operant conditioning because avoiding those cues provides short-term relief and maintains the alarm response over time.

Children who don’t develop a healthy sense of control have difficulty coping with adversity later on.

Some people are highly reactive to bodily sensations linked to anxiety and interpret them as dangerous (anxiety sensitivity).

Social / Environmental Factors

Bad caregiving teaches the child that the world is unpredictable and unsafe.

Overprotective parenting (the child never learns to do things on their own).

Seeing others act anxious can teach you to be anxious too.

Women are taught to show anxiety, while men are taught to hide it.

Major life stressors (e.g., divorce, death of a loved one, job loss, moving) can trigger or worsen anxiety.

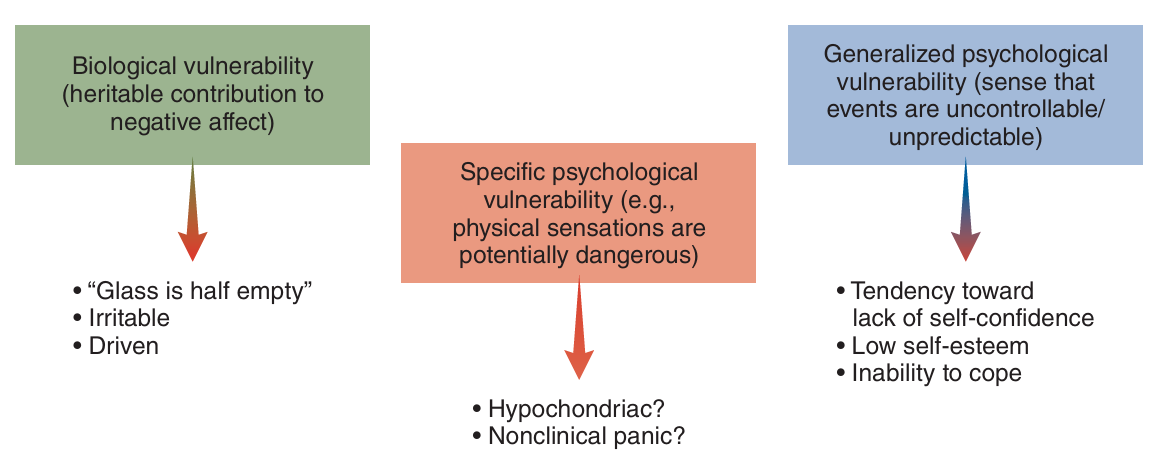

What are the three vulnerabilities that contribute to the development of anxiety disorders?

What is the relationship between anxiety disorders and suicidal ideation or behaviour, and which disorders show the strongest links?

Having an anxiety disorder increases the chances of having thoughts about suicide (suicidal ideation) or making suicidal attempts (suicidal behaviour). However, the relationship is strongest with panic disorder and PTSD, both of which show higher rates of suicidal thoughts and behaviours compared to other anxiety disorders.

What is Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), and how is it diagnosed?

Worry about uncertainty in events of everyday life. Diagnosed when a person experiences excessive anxiety and worry about various events or activities, occurring more days than not for ≥6 months, and finds it difficult to control the worry, with ≥3 physiological symptoms. Symptoms must also cause significant distress or impairment.

Symptoms include:

Restlessness

Easily fatigued

Difficulty concentrating

Irritability

Muscle tension

Sleep disturbances

According to the Cognitive Avoidance Model, what is the problem in GAD, and what treatment approaches are designed to address this problem?

The problem is worry, because worry functions as a form of avoidance. It prevents the person from fully engaging with the mental images and emotions associated with their worries, which brings short-term relief but keeps the worry going. Treatment focuses on imaginal exposure to worried about situations and reducing safety behaviours (e.g., reassurance seeking).

According to the Metacognitive Model, what is the problem in GAD, and what treatment approaches are designed to address this problem?

The problem is beliefs about worry. Positive beliefs (e.g., “Worrying helps me stay prepared”) make the person think worrying is useful, so it reinforces the worrying. Negative beliefs (e.g., “My worrying is uncontrollable and harmful”) create worry-about-worry, which keeps the cycle going. Treatment focuses on challenging beliefs about worrying, attentional training, and mindfulness.

What is Panic Disorder (PD), and how is it diagnosed?

Fear of losing control / something bad happening because of panic symptoms. Diagnosed when a person has recurrent, unexpected panic attacks, followed by ≥1 month of persistent worry about having more attacks or their consequences, and/or behaviour changes to avoid triggering another attack. Panic attacks are sudden surges of intense fear or discomfort that peak within minutes and include ≥4 symptoms.

Symptoms include:

Pounding heart

Sweating

Trembling or shaking

Shortness of breath

Feelings of choking

Chest pain / discomfort

Nausea / abdominal distress

Dizzy, unsteady, light-headed

Chills or heat sensations

Numbness / tingling

Detachment from reality or self

Fear of losing control / “going crazy”

Fear of dying

What is Agoraphobia, and how is it diagnosed?

Fear of situations where escape or support might be difficult if something goes wrong. Diagnosed when a person feels intense fear or anxiety in ≥2 specific situations.

These specific situations include:

Public transportation

Open spaces (e.g., parking lots)

Enclosed places (e.g., movie theatre)

Crowds or lines

Being outside of the home alone

According to the Panic Control Treatment Model, what is the problem in Panic Disorder (with or without Agoraphobia), and what treatment approaches are designed to address this problem?

The problem is interpretations of bodily sensations. After a panic attack, a person may learn to associate certain bodily sensations with danger, and those same sensations act as learned alarms that trigger panic in the future. This cycle continues through negative reinforcement, where the person avoids things that might provoke those bodily sensations. This avoidance provides short-term relief but maintains the fear. Other factors include anxiety sensitivity and catastrophic thinking (e.g., “My heart is racing, I’m going to die”). Treatment focuses on interoceptive exposure to feared bodily sensations, in-vivo exposures to feared situations, challenging catastrophic beliefs about panic, and breathing retraining.

What is a Specific Phobia, and how is it diagnosed?

Fear of a specific object or situation. Diagnosed when a person has intense fear or anxiety about a specific object or situation, which is actively avoided or endured with intense distress. The fear is out of proportion to the actual danger, lasts ≥6 months, and causes significant distress or impairment.

Different subtypes of phobias include:

Animal (e.g., dogs, spiders)

Natural environment (e.g., heights, water)

Blood-injection-injury (e.g., needles)

Situational (e.g., airplanes, elevators)

Other (e.g., fear of choking / vomiting)

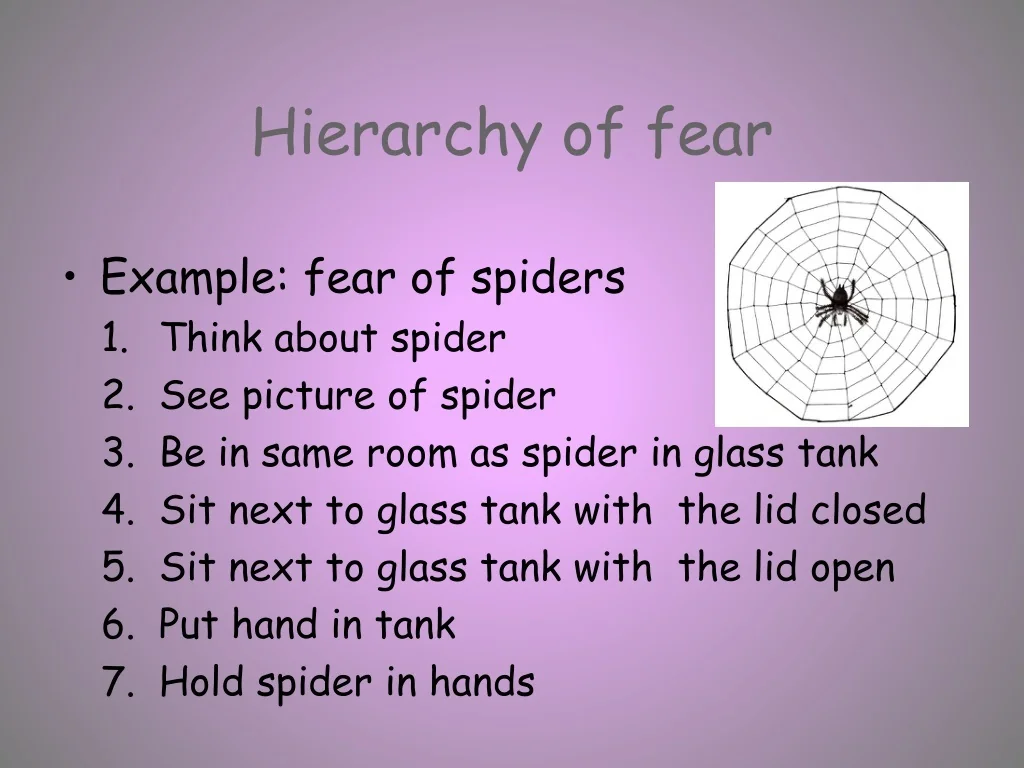

According to the Exposure Therapy Model, what is the problem in Specific Phobias, and what treatment approaches are designed to address this problem?

The problem is that phobias are developed through learned alarms (can be the result of true or false alarms) and maintained through avoidance. Treatment focuses on gradual exposure to the feared object or situation, either in vivo (real life) or through virtual reality.

What is Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD), and how is it diagnosed?

Fear of being negatively evaluated by others. Diagnosed when a person has intense fear or anxiety in social situations where they may be judged, embarrassed, or rejected. The person avoids these situations or endures them with intense distress. The fear is out of proportion to the actual threat, lasts ≥6 months, and causes significant distress or impairment.

These situations include:

Interacting with other people

Being observed

Performing in front of others

What biological factors are believed to contribute to the development of SAD?

Biological factors believed to contribute to SAD include an inherited tendency to fear angry, critical, or rejecting people. Research shows that people with SAD who look at pictures of faces are more likely to remember those with critical expressions. They also react to angry faces with greater activation of the amygdala and less cortical control or regulation than people without anxiety. Another contributing factor is excessive behavioural inhibition in infancy or early childhood.

According to the Cognitive Model, what is the problem in SAD, and what treatment approaches are designed to address this problem?

The problem is distorted perceptions of social situations and engaging in behaviours that maintain the fear. Individuals often set unrealistically high self-standards, experience an intense fear of judgement, and hold negative beliefs about themselves, which leads to avoidance and reliance on safety behaviours (e.g., avoiding eye contact or speaking quietly to avoid embarrassment). Treatment focuses on cognitive restructuring to challenge these negative beliefs about social situations, and exposure therapy that encourages directing attention toward others rather than the self, while reducing the use of safety behaviours.

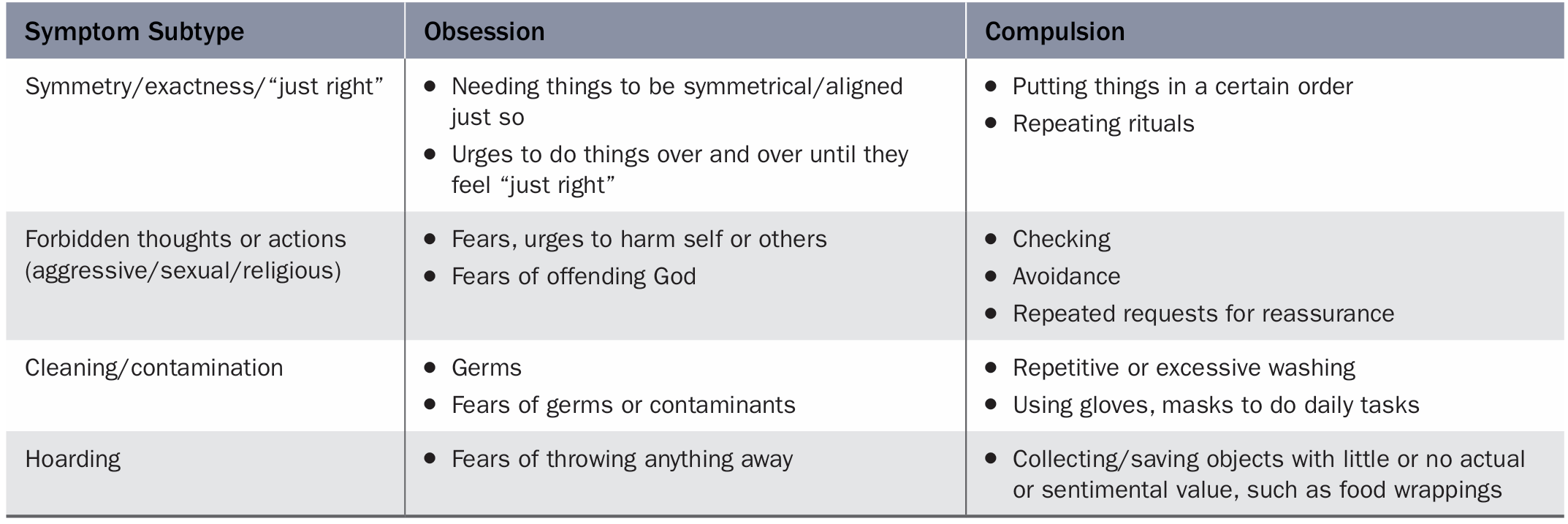

What is Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), and how is it diagnosed?

Obsessions and/or compulsions that are time-consuming or distressing / impairing. Diagnosed when a person has obsessions (recurrent, intrusive thoughts, urges, or images that cause anxiety) and/or compulsions (repetitive behaviors or mental acts performed to reduce anxiety or prevent a feared event). These are time-consuming (≥1 hour/day) or cause significant distress or impairment. The person usually recognizes the thoughts or behaviors as excessive or unreasonable.

According to Emotional Processing Theory, what is the problem in OCD?

The problem is maladaptive fear structures (exaggerated and inaccurate associations) that do not get corrected because individuals engage in compulsions and avoidance behaviours that temporarily reduce anxiety but prevent them from learning that their feared outcomes are unrealistic or unlikely.

According to Cognitive / Responsibility Theory, what is the problem in OCD?

The problem is maladaptive beliefs, such as overestimation of threat, thought-action fusion, and an inflated sense of responsibility to prevent harm to oneself or others. These beliefs are maintained and reinforced by compulsions and avoidance behaviours.

How does Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) address the problems identified in both Emotional Processing and Cognitive / Responsibility Theory?

The exposure component of ERP involves confronting the feared stimuli, either in vivo (real life) or through imagination. The response prevention component requires the person to refrain from performing compulsions or avoidance behaviours, which normally serve to reduce anxiety in the short term. This process helps correct maladaptive fear structures (from emotional processing theory) and challenge maladaptive beliefs (from cognitive / responsibility theory), making ERP the gold standard for OCD treatment.

What is Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and how is it diagnosed?

Failure of natural recovery following a traumatic event. Diagnosed when a person is exposed to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence in one (or more) of the following ways: directly experiencing the event, witnessing it in person, learning that it happened to a close family member or friend, or repeated exposure to details of the trauma. Diagnosis also requires the presence of symptoms from each of four clusters (intrusion / reliving, avoidance, negative cognitions / mood, and changes in arousal / reactivity), lasting ≥1 month and causing significant distress or impairment.

What biological mechanisms are thought to underlie PTSD?

People with PTSD often have an overactive amygdala, which constantly triggers the alarm response. The prefrontal cortex is underactive, so it fails to calm down the amygdala. In addition, individuals with PTSD tend to have reduced volume in the hippocampus, which is important for memory consolidation. This might make it difficult to distinguish past from present.

According to Emotional Processing Theory, what is the problem in PTSD, and what treatment approaches are designed to address this problem?

The problem is maladaptive fear structures that do not get corrected. PTSD symptoms are maintained by these maladaptive fear associations and meaning-making, which refers to the personal story or interpretation the person attaches to the traumatic event. For example, someone might believe “I should have done more to stop it” or “It was my fault.” These beliefs keep the person stuck in the trauma and unable to move past it (stuck points). Avoidance of trauma-related memories, thoughts, or reminders prevents these fear structures from being corrected.

How does Cognitive Processing Therapy address the cognitive and meaning-making aspects of PTSD, as identified by Emotional Processing Theory?

Focuses on the meaning-making aspect of PTSD by helping individuals challenge the beliefs that keep them stuck in their trauma through cognitive restructuring. The goal is to create a new, healthier understanding or story of why the trauma occurred. This approach targets the cognitive part of CBT.

How does Prolonged Exposure address the behavioural and maladaptive fear association aspects of PTSD as identified by Emotional Processing Theory?

Focuses on correcting the maladaptive fear association aspects of PTSD by using imaginal exposure to the trauma memory and in-vivo exposure to trauma reminders. By doing this, the individual learns that these memories and reminders are not dangerous. This approach targets the behavioural part of CBT.