Types of steels and alloy steels

1/11

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

12 Terms

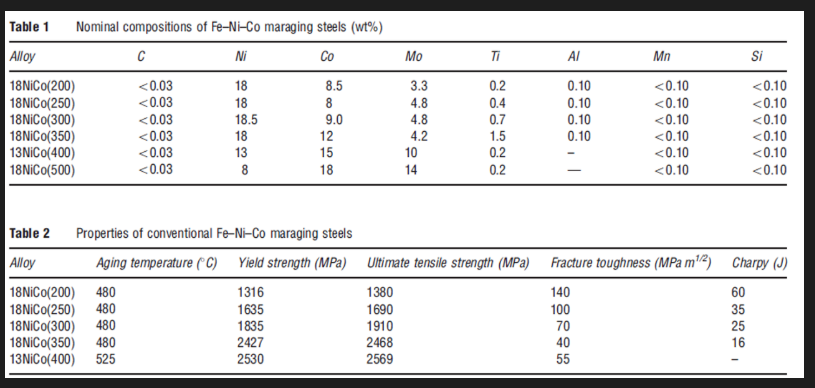

Maraging steels

Special class of ultra high strength low C steel. Martensite age hardening and denotes the hardening of Fe-Ni lathe martensite matrix. Not hardened through C so hardenability isnt a problem. C is considered an impurity. Strengthened by precipitation of intermetallic compounds (ex Ni3Mo) at temperatures of 480. Martensite after annealing is relatively soft. Carbon can form carbides which affect the toughness of these steels. Good weldability and fracture toughness, only slight dimensional changes. Very high strength and toughness. Very high amount of alloying elements.

Typically a lot of nickel. Cobalt reduces the solubility of Mo in the steel and increases the volume fraction of Ni forming Ni3Mo.

Characteristics:

YS 1300 to 2500 MPa

Typical alloy content: 18% Ni, up to 13% Co, 3-5% Mo, very low C content

The absence of C and the use of intermetallic precipitation to achieve hardening produces several unique characteristics.

Hardenability is of no concern

The low C martensite formed after annealing is relatively soft about 30 to 35 HRC

During age hardening, there are only very slight dimensional changes. Fairly intricate shapes can be machined in the soft condition and then hardened with a minimum of distortion. Heat to austenite then quench to martensite.

Weldability is excellent (no risk of forming martensite)

Fracture toughness is considerably better than that of conventional high strength steels.

Applications:

Production tools (punches, casting and forging dies, springs, extrusion pressing rams and containers)

Military (canon recoil springs, light military bridges, missile skin, rocket motor cases)

Aerospace (forgings, fan shafts, arresting hooks, shock absorbers)

Auto racing (shafts, gears, rods, crankshafts)

High strength structural and high strength low alloy steel

YS over 275 MPa

Displays ductile to brittle transition

Hot rolled C-Mn structural steels.

Mn in a mild solid solution strengthener in ferrite and the principal strengthening element when in amounts over 1% in rolled low C (<0.2 %C) steels. Hot rolled Mn steels can attain YS in the range of 290 to 380 MPa. If structural plate or shapes with improved toughness are required, small amounts of Al are added for grain refinement.

Heat treated C steels.

Heat treatments can be used to improve the mechanical properties of structural plate, bar and structural shapes.

Normalising: Pearlite-ferrite microstructure with a finer grain size to hot rolled condition. Fine grain size makes the steel stronger, tougher and more uniform. YS range of 290 to 350 MPa.

Quenching: from 900 degrees and tempering 480 to 600 degrees. Tempered martensite/bainite structures. Better combinations of strength and ductility. C-Mn with up to 0.25% C have low hardenability which section size restricted to 15 cm. YS of 300 to 700 MPa.

Applications: shafts, coupling, axles, laminated spring materials (generally carbon >0.4 wt%)

Heat treated low alloy steels.

Low alloy steels.

Contain Mn, Si, Cu in quantities greater than the max. limits (1.65% Mn, 0.6% Si and 0.060% Cu)of carbon steel

OR

Contain alloy elements, including C up to a total alloy content of about 8%

Except microalloyed (containing V,Nb,Ti only) steels, most low alloy steels are suitable for Q&T.

Better hardenability than C steels

High strength and good toughness in thicker sections.

Increased alloy content makes it more difficult to weld and more expensive.

In plate or bar form

Quenched and tempered steels have carbon contents in the range of 0.10 to 0.45%, with alloy contents, either singly or in combination, of up to 1.5% Mn, 5% Ni, 3% Cr, 1% Mo, 0.5% V, 0.10% Nb.

Can contain small amounts of Ti, Zr and/or B.

Generally, the higher the alloy content, the greater the hardenability. The higher the C content, the greater the available strength.

Effects of tempering low alloy steels

Improves toughness of the as-quenched martensite

Lowers strength and increase ductility

Softens steel due to the rapid coarsening of cementite with increasing tempering temp. and a reduction in dislocation density

Alloying element can help delay the degree of softening during tempering and certain elements (Mo, Cr, V, Nb and Ti) are more effective than others.

HSLA, high strength low alloy steel: forms carbides and nitrides due to alloys, restricting grain growth, austenite to ferrite grains, good formability and weldability. Utilises small amounts of alloying elements in the as-rolled or normalised condition. (sheet, strip, bar, plate and structural sections).

Microalloy steels contain concentrations of one or more strong carbides and nitride forming elements.

Better mechanical properties than as-rolled C steels.

Weldability better or comparable to mild steel

Elements added: Nb, V, Ti and Al to obtain fine ferrite grain size. V (0.03 - 0.1 wt%), Nb (0.02-0.1 wt%) and Ti (0.01 wt% - 0.02%) combine preferentially with carbon and/or nitrogen to form a fine dispersion of precipitated particles in the steel matrix

Strength increases by reduced grain size, dispersion strengthening (carbides and nitrides) and solution hardening (Mn, Si, uncombined N)

Controlled rolled (thermomechanical process) microalloyed steels are increasingly being applied to obtain optimum mechanical properties.

YS up to 550 MPa

HSLA main categories

Dual phase steels

DP steels can exhibit high strength and very good formability if they are heat treated to produce a microstructure consisting of a matrix of polygonal ferrite with islands of martensite (10-20% by volume)

Exhibit continuous yielding and a relatively low yield stress (300-350 MPa)

These can be produced from low-C steels (<0.1wt%C) in 3 ways:

Intercritical austenitization of carbon-manganese steels followed by rapid cooling.

Hot rolling with ferrite formers such as silicon and transformation-delaying elements such as chromium, manganese, and/or molybdenum

Continuous annealing of cold-rolled carbon manganese steel followed by quenching and tempering

Continuous yielding behaviour and a low proof strength and higher total elongation than other HSLA steels of similar strength. DP steel can be formed just like low-strength steel but they can also provide high strength in the finished component because of their rapid work-hardening rate.

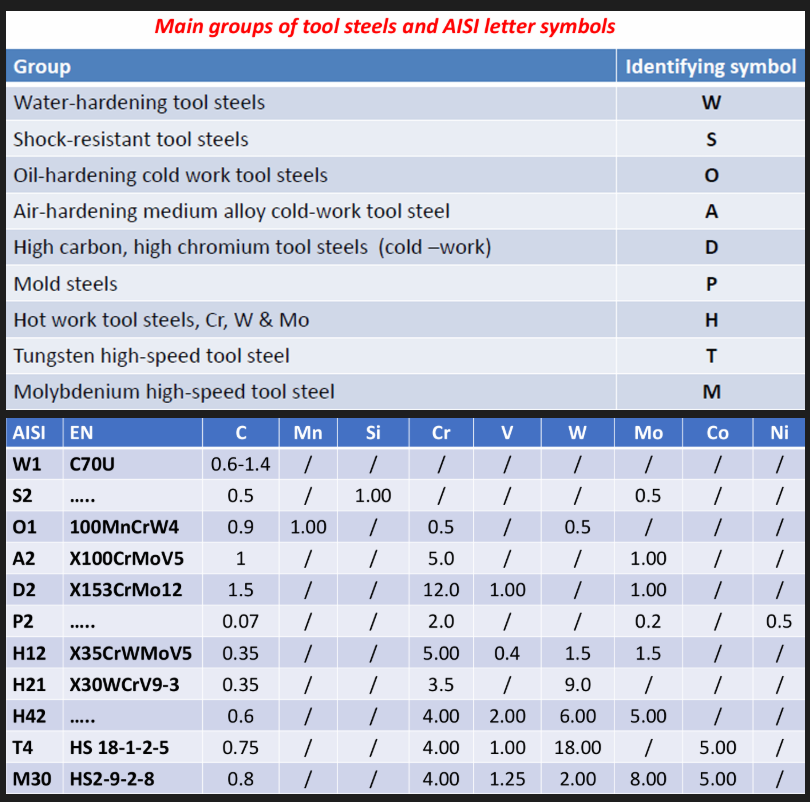

Tool steels

General principles:

Hardened microstructure is typically tempered martensite containing various dispersions of Fe and alloy carbides. Used in tempered martensitic structures.

High C + alloying promote high hardenability

The higher the C and alloy content, the greater the supersaturation in martensite and the higher the density of carbides that can be produced during tempering.

Strong carbides formers are stables in austenite during hot working. These carbides are retained in the microstructure together with those formed during tempering.

The higher the C content of martensite and the density of carbides, the higher the hardness, wear resistance but the lower the toughness of a tool steel microstructure.

High speed steel (HSS) (T and M series)

High C, most highly alloyed

High hardenability

Microstructure with high faction of high temp. stable carbides

Low/medium distortion.

Low (Mo)/medium (T) resistance to decarburisation

Low toughness

Excellent wear resistance and red hardness (high temp. hardness)

Retains hardness even when operated continuously at temps of 650 degrees

High temp. hardness obtained by alloying with W, Mo, V and Cr

Applications: high speed cutting tools

Hot work steels (H series)

Medium C content and strong carbides formers

Based on Cr (H1-19), W (H20-39) and Mo (H40-59)

Used at elevated temps.

Resistant to high temp impact loading

Very high resistance to softening (best for W, Mo based) and thermal fatigue

Excellent hardenability; low distortion; M-H toughness (best Cr HW steels), M-H wear resistance. Good temp. strength achieved by tempering at high temps. when fine stable dispersion of carbides precipitate.

Applications: hot forming ex forging and die casting

Cold work steels (A,D,O series)

High resistance to wear and cracking under cold working conditions

O type: oil hardening, medium hardenability, high C martensite with fine carbide dispersion (low tempering temp.), high machinability, medium toughness, low resistance to softening, medium wear resistance, low distortion, high resistance to decarburisation.

A type: air hardening, medium alloy, high C martensite and fine carbide dispersion, high hardenability, very low distortion, medium machinability, medium toughness, high softening resistance, medium to high wear resistance

D type: high C and Cr, high C martensite with large volume % of alloy carbides, extremely high wear resistance, low toughness, medium resistance, low toughness, medium resistance to decarburisation, low machinability, high resistance to softening

Applications: dies and moulds for cold working applications

Mould steel (P series)

Low C content permits machining cavities (high machinability)

Surface treatment ex carburising and hardening required to improve hardness and wear resistance (medium)

Very high resistance to decarburisation, low resistance to softening and low distortion. Sometimes martensitic stainless steels used for applications requiring high corrosion resistance

Applications: plastic injection moulding, metal die casting

Shock resistant steels (S series)

High toughness and fracture resistance together with high strength and wear resistance under impact loading.

Accomplished using moderate C% and fine carbides dispersion. Si content usually high.

Characteristics:

Very high toughness

Medium-high machinability

Low-medium distortion

Medium-low wear resistance

Low resistance to decarburistion

Carburisation: heat to austenite, carbonised gas, carbon will diffuse in steel

Applications: die, punches, chisels

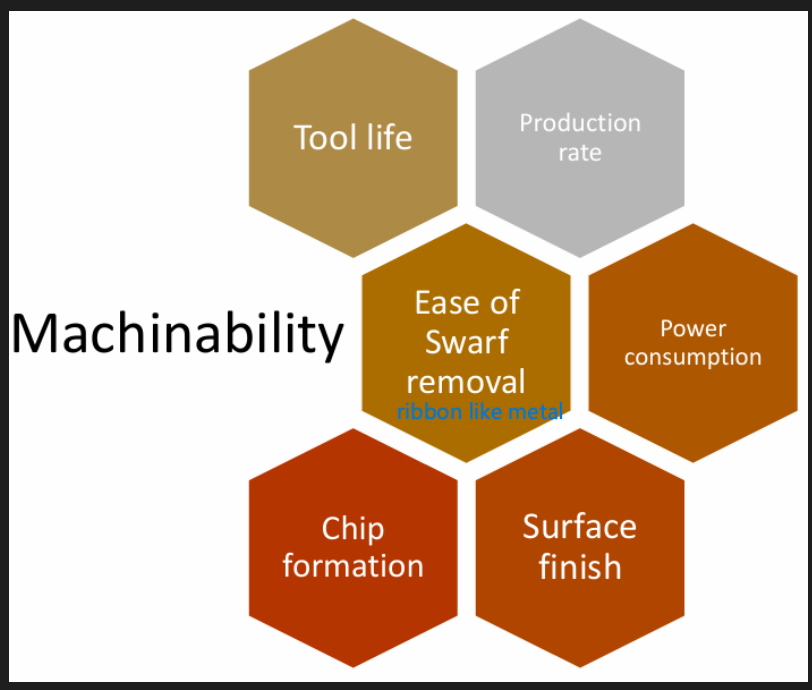

Machinability

Costly (60% of cost for automotive transmission parts). Helps process other materials. Operations include: drilling, milling and grinding. Each operation has different processing conditions ex temp., strain rate and chip formation.

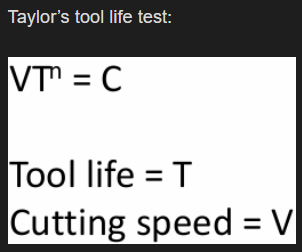

Machinability: Machinability test

Typical n values for HSS range from 0.1 to 0.2. Hence small variations in cutting speed would result in big changes in tool life. More practical to measure machinability as the cutting speed necessary to cause tool failure within a specified period.

Effect of C and pearlite content on cutting speed. Cutting speed for 60 min tool (cutting speed at which tool fails after an hour) life in steels containing different amounts of C and pearlite, 0.65 mm² cross sectional area; carbide tool. If carbon is increased, more difficult to machine as more carbides present.

Machinability: Optimum microstructure

Different C compositions have different optimal microstructures

0.06 to 0.2% C as rolled (most economical)

C content lower than 0.15% means that the steel has a low strength in the annealed state and is soft and gummy. Steel will adhere to the cutting tool. Work hardening ex rolling, will help in machinability to increase strength and lower ductility.

0.15 to 0.3% C small bars (less than 75 mm) normalised, larger bars as rolled

Machined satisfactorily in as rolled, as forged, annealed or normalised condition. Microstructure predominantly pearlite.

0.3 - 0.55% C best if annealed

To produce a mixture of lamellar and spheroidite, otherwise the strength and hardness would be too high for optimum machinability.

0.55 %C 100% spheroidite from coarse to fine

Hardened and tempered structures are generally not desired for machining

Machinability: Alloying elements and machinability

To improve machinability

S (0.1 to 0.3%) is most widely used (cheapest) cutting additive. Added with sufficient amount of Mn to form MnS (4:1) and not FeS (causes hot shortness. MnS deform into planes during chip formation, MnS facilitates chip breakage and lubricates tool-chip interface. Improves surface finish, reduces friction and cutting temp. Morphology of inclusion when elongated will reduce transverse mechanical properties Some alloying elements are added to turn MnS into a globular form.

Pb (0.15 to 0.35%). Will solidify into small Pb particles as it is insoluble in molten steel (due to high density care to avoid segregation). Melts at elevated temps. during cutting therefore provides internal lubrication, reduces friction, cutting temp. and forces, reduces tool wear (diffusion barrier). Associated with the tails of MnS inclusions in resulphurised teel. This reduced deformation ratio of MnS and improves their function to initiate cracks/act as stress concentrators. It improves surface finish. Highly toxic: good extraction needed during melting and casting.

Te (max. 0.1%) Present as MnTe. Low melting point compound (it behaves like Pb). Will melt at elevated temps. during cutting. MnS also becomes more globular (avoids issues with strength). Expensive, can lead to cracking during hot working in high quantities.

Se (0.05-0.1%) for low alloys, 0.15% for high alloy steels. Improves MnS globularity.

Bi replaces Pb. Melts when cutting

P (up to 0.1%). Strengthens/embrittles ferrite. Increases hardness. Chips less continuous and better surface finish.

Ca (non-traditional). May be added to form Ca aluminates to soften during machining and form a protective layer on the tool. Length of MnS inclusions becomes shorter therefore improving transverse properties of free machining steels.

These improve surface finish and reduce frictional forces

Machinability defectors (bad for machining):

Deoxidiers (react with O in steel to form very hard components, damage the tool)

Si

Al will create alumina in the steel (oxides) which will make it more difficult to machine the steel.

Ti

Zr

Strengtheners:

V

Bo

Free cutting steel (low C) and machinable low alloy steel

Pb and S used to improve machinability. Ex: 0.25% S, 0.25% Pb and 0.08% Bi (low toughness, low corrosion resistance, difficulties in hot working). Applications: minimal performance requirement/less critical parts ex: spark plug bodies, non-load bearing automotive components, household components. Machinable low alloy steel uses alloying elements to modify shape and size of MnS inclusions. Traditionally based on Pb additions rather than S.

Free cutting steel (medium C)

Free cutting medium C (0.35-0.5% C, 1.5% Mn) steels are used in the normalised conditions for higher components requiring TS up to 1000 MPa. Machinability is less than free cutting low C steel. Silicate inclusions do not significantly impair machinability with carbide tools as in the case of low C free cutting stees. Inclusions soften at high temps generated during machining. Alumina particles are however still detrimental. Alumina particles can still result in problems with machining

Machinable low alloy steel.

Traditionally these steels were based on Pb rather then S. The introduction of alloy additions that modify the morphology of MnS inclusions made it possible to achieve the high strength requirements with resulphurised steel.

Sheet formability

Formability is the ability of a material to maintain structural integrity while being plastically deformed. Preferred low C steel (typically <0.1 %C and <1% intentional and residual alloying elements) for low strength but good ductility. Mn principal alloy ranges between 0.15 and 0.35%. Si, Nb, Ti, Al may be added as deoxidisers or to develop certain properties. Residual elements (S, Cr, Ni, Mo, P, N, Cu) are usually limited as much as possible.

Effect of alloying elements on sheet formability

S and P limited to 0.035% P and 0.040%S due to cracking and splitting

Cr, Ni, Mo, V increase strength and reduce formability

Al aids in reducing thinning and combines with N to reduce strain ageing

Bulk formability

Increases the surface to volume ratio of the formed part under action of large compressive stresses. Plastic deformation is prevalent making elastic recovery after deformation very small. Flow stress, failure behaviour, metallurgical transformations are important material characteristics that will affect the bulk formability.

Weldability

Low C steels: below 0.3% C and <0.05wt% S readily welded with little need of special measures to avoid cracking. Thick sections may need pre-heating to 40 and stress relieving at 525 to 675.

Medium C steels: heat affected zone will likely be hard, low in toughness and susceptible to cold cracking. Preheating and post heating can be used to slow down the cooling rate or temper any martensite. Hydrogen is a problem

High C steels: difficult to weld. Low H2 welding procedure must be used. Preheating may be used to reduce shrinkage stresses and post heating must be used to temper the martensite.