Topic #8: Bioenergetics

1/41

Earn XP

Description and Tags

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

42 Terms

Bioenergetics

Study of energy transformations and exchanges in living organisms

Focus: How organisms obtain and use energy (chemical, osmotic, mechanical, etc.)

Energy sources: Sunlight and/or chemical nutrients

Key concept: Organisms couple energy-generating processes with energy-requiring ones

ENergy: ability to do work (chemical, osmotic, mechanical,etc)

Thermodynamics of Life

Organisms require ongoing energy to work, survive, and reproduce

Energy is needed to resist the natural trend toward disorder (entropy) and low energy (as described by thermodynamics)

Living things maintain high energy and low disorder, staying in nonequilibrium with the universe (living organisms are not at equalibrium w/universe)

Death and decay restore equilibrium with the universe

Life is an Open System

I. Living organisms are open systems

A. Constantly exchanging matter & energy with the universe, but not at equilibrium

II. In most cases, [particular matter] remains constant over time in a living organism

A. How is this possible if living organisms are not at equilibrium with universe?

Steady State

Living organisms are at steady state ( all flows of matter are constant, like constant flow in/out)

A. All flows of matter into, within, & from living organisms are constant

1. No dramatic change with time

2. kEntry = kUtilization + kExit = constant [particular matter]

Maintaining Steady State

Small changes can disrupt steady state, but organisms adjust matter intake, use, or output to restore it

Maintaining steady state requires ongoing work

Constant energy flow in and out is essential for this process

Gibbs Free Energy

Only a certain portion of all the energy that living organisms obtain can be used to do work

Free energy is the portion of energy we can access

A. Gibbs free energy (G)

1. G = H – TS

i. H = enthalpy (total heat content of system)

ii. T = temperature of system

iii. S = entropy (total disorder/randomness of system)

Measuring Free Energy

It is difficult to measure G, H, S directly

A. It is very easy to measure changes (Δ) in each of these quantities 1. ΔG = ΔH – TΔS

ΔH

I. Change in enthalpy or heat (q) content of system under constant pressure conditions (can either increase or decrease)

A. Exothermic process: gives off q

1. -ΔH: enthalpically favorable process (no neg. heat just shows that heat is leaving system)

B. Endothermic process: absorbs q

1. +ΔH: enthalpically unfavorable process (+ heat is coming into system)

ΔS

Change in entropy or disorder/randomness of the system

A. More disorder in the system

1. +ΔS: entropically favorable process

B. Less disorder in the system

1. -ΔS: entropically unfavorable process

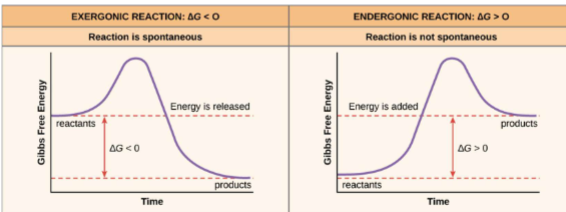

ΔG

Change in free energy

A. Measure of the spontaneity of a process

1. Likelihood that a process will spontaneously occur without some type of active intervention

B. Endergonic process: absorbs G

1. +ΔG: nonspontaneous, unfavorable process (does not mean it wont occur just not by itself)

C. Exergonic process: gives off G

1. -ΔG: spontaneous, favorable process (it will occur on its on)

Spontaneity sign of delta G, H, S

Favorability/ spontaneity says nothing abt kinetics of process

ΔG & Chem. rxns pt1

ΔG of chemical reactions

A. ΔG = G (Products) – G(Reactants)

1. G(Products) > G(Reactants): +ΔG (endergonic reaction)

2. G(Products) < G(Reactants): -ΔG (exergonic reaction)

whether rxn is favorable or not you always need some energy there

ΔG & Chem. rxns pt2

ΔG of a reaction is independent of the reaction pathway (not about how products form)

Comparing ΔG values only makes sense under standardized conditions

Standard conditions allow meaningful comparison between reactions

Standard Free Energy Change

I. ΔG° (delta G naught): standard ΔGG

A. ΔG under “standard conditions”

1. T = 298 K (25°C); P = 1 atm

2. [Reactant] & [Product] = 1 M

3. pH = 0 (1 M [H+])

II. ΔG° ́(delta G naught prime): biochemical standard ΔG

A. Same conditions, but pH = 7.0 (1 x 10-7 M [H+], 55.5 M [H2O]); because most biochemical reactions occur at this pH)

Calc. ΔG°

I. ΔG° ́ = -RT ln K ́eq

A. R is gas constant (8.315 J/mol ● K)

B. ΔG° ́ is constant

1. This reveals the direction of a biochemical reaction & how far it must proceed to reach equilibrium at biochemical standard conditions

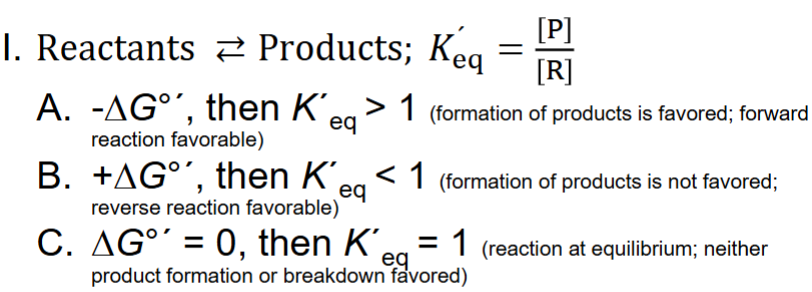

Info. Obtained from ΔG° ́

fwd rxn is favored (formation of product)

reverse rxn favored

+: Endergonic

-: Exergonic

ΔG vs ΔG° ́

ΔG (actual free energy change) often differs from ΔG° ́ (standard free energy change)

This is because real cellular conditions usually differ from standard conditions

Relationship: Δ G = ΔG° ́+ RTln

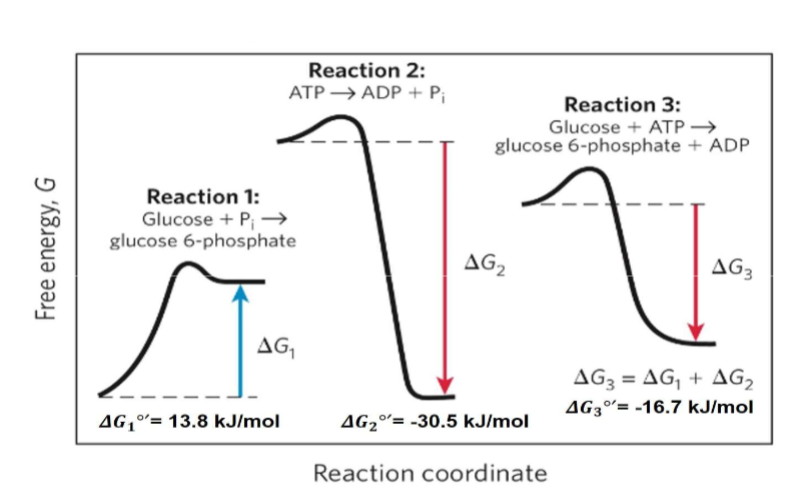

Reaction Coupling in Living Organisms

Endergonic reactions (require energy) need external energy input in lab settings

Living organisms solve this by coupling endergonic reactions to exergonic ones

Energy released from favorable (exergonic) reactions drives unfavorable (endergonic) reactions

Living things cannot make endergonic rxns go

example of free energy change

-living organisms do not make endergonic processes go

rxn 1 cant happen by itself, rxn 2 can happen by its self, rxn 3 can happen by itself (energy releasing proces with something that requires it-how they make these processes go)f

Sources of Biochem. Energy

Stage 1: Digestion – Proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids are broken down into amino acids, glucose, and fatty acids.

Stage 2: Oxidation of C-Skeletons – Amino acids, glucose, and fatty acids are converted to pyruvate or directly to acetyl-CoA.

Stage 3: Oxidation of Acetyl-CoA (TCA Cycle) – Acetyl-CoA enters TCA (Krebs) cycle, releasing 2CO2 and generating electron carriers NADH and FADH2

Stage 4: Electron Transport & ATP Production – NADH & FADH2 donate electrons to the electron transport chain, driving oxidative phosphorylation and ATP synthesis; electrons end up reducing O2 to water.

![<ul><li><p class="my-2 [&+p]:mt-4 [&_strong:has(+br)]:inline-block [&_strong:has(+br)]:pb-2"><strong>Stage 1: Digestion</strong> – Proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids are broken down into amino acids, glucose, and fatty acids.</p></li><li><p class="my-2 [&+p]:mt-4 [&_strong:has(+br)]:inline-block [&_strong:has(+br)]:pb-2"><strong>Stage 2: Oxidation of C-Skeletons</strong> – Amino acids, glucose, and fatty acids are converted to pyruvate or directly to acetyl-CoA.</p></li><li><p class="my-2 [&+p]:mt-4 [&_strong:has(+br)]:inline-block [&_strong:has(+br)]:pb-2"><strong>Stage 3: Oxidation of Acetyl-CoA (TCA Cycle)</strong> – Acetyl-CoA enters TCA (Krebs) cycle, releasing 2CO2 and generating electron carriers NADH and FADH2</p></li><li><p class="my-2 [&+p]:mt-4 [&_strong:has(+br)]:inline-block [&_strong:has(+br)]:pb-2"><strong>Stage 4: Electron Transport & ATP Production</strong> – NADH & FADH2 donate electrons to the electron transport chain, driving <strong>oxidative phosphorylation</strong> and ATP synthesis; electrons end up reducing O2 to water.</p></li></ul><p></p>](https://knowt-user-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/58345110-92cb-4723-ad54-6707aa6f6226.png)

“High-Energy” Compounds

Exergonic reactions of nutrient oxidation release G that’s trapped within chemical bonds of “high-energy” compounds

A. Their hydrolysis releases this G to drive endergonic reactions

B. Variety of molecules function as “high- energy” compounds

1. Most important are molecules containing phosphate groups (most important one is ATP)

ATP: Universal Cellular G Currency

ATP (adenosine triphosphate) is a nucleotide (adenine + ribose + 3 phosphates).

ATP is the main energy currency in cells (important

supplier/transmitter (currency)

of G in living organisms)

Last two phosphates joined by high-energy phosphoanhydride bonds.

Hydrolysis of these bonds releases energy for cellular processes.

ATP Energy Transmission

ATP transmits energy by hydrolyzing phosphoanhydride bonds, releasing a phosphoryl group for transfer to other molecules (group transfer).

Example: ATP + Molecule–OH → ADP + Molecule–O–PO₄²⁻ (substrate phosphorylation).

ATP’s bonds are stable in water but easily hydrolyzed by enzymes.

Hydrolysis releases energy in a controlled way for cellular work, not as heat

![<ul><li><p class="my-2 [&+p]:mt-4 [&_strong:has(+br)]:inline-block [&_strong:has(+br)]:pb-2"><strong>ATP transmits energy</strong> by hydrolyzing phosphoanhydride bonds, releasing a phosphoryl group for transfer to other molecules (group transfer).</p></li><li><p class="my-2 [&+p]:mt-4 [&_strong:has(+br)]:inline-block [&_strong:has(+br)]:pb-2">Example: ATP + Molecule–OH → ADP + Molecule–O–PO₄²⁻ (substrate phosphorylation).</p></li><li><p class="my-2 [&+p]:mt-4 [&_strong:has(+br)]:inline-block [&_strong:has(+br)]:pb-2"><strong>ATP’s bonds</strong> are stable in water but easily hydrolyzed by enzymes.</p></li><li><p class="my-2 [&+p]:mt-4 [&_strong:has(+br)]:inline-block [&_strong:has(+br)]:pb-2">Hydrolysis releases energy in a controlled way for cellular work, not as heat</p></li></ul><p></p>](https://knowt-user-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/1a41d8ae-c5e1-402a-a6f0-3ef95e8fe1d8.png)

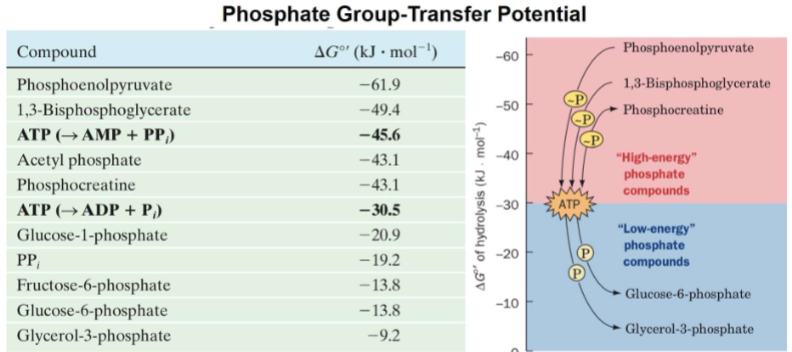

Phosphate Group-Transfer Potential

ATP is one of several high-energy phosphate compounds.

Compounds are ranked by phosphate group-transfer potential (how easily they transfer phosphoryl groups).

Molecules with higher potential than ATP can generate ATP by transferring phosphate to ADP/AMP.

Molecules with lower potential than ATP can be phosphorylated by ATP (ATP transfer of phosphoryl group to them)

Phosphate Group-Transfer Potential

look at release of phosphoro groups

-: exergonic

know how to interpret table

most negative -61.9 (higher potential)

making ATP

ex Q: which of compounds would atp be used to make

Misnomer of “High-Energy” Bonds

“High-energy” bonds are not “special” or “unique” bonds

A. Called “high-energy” because hydrolysis of these bonds very resonance & electrostatically stable compared to “high-energy” bond

B. very reactive & require lower- than-normal amounts of G to break (sometimes called strained bonds)

ATP Utilization pt1

Processes in which ATP is utilized for G

A. Early stages of nutrient oxidation

1. Used to produced phosphorylated intermediates that are trapped within cells

i. Preserves [nutrient] gradients (keeps them moving into cells)

ii. Commits these intermediates to certain metabolic processes

[]= concentration

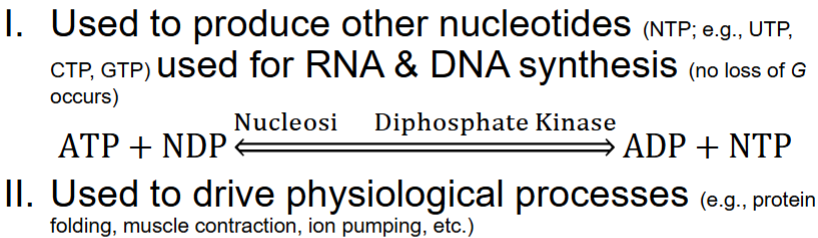

ATP Utilization pt2

atp used to make other nucleotides

when u do this not losing energy

Responsible for this is : nucleoside diphosphate kinase

is a reversable rxn

ATP Utilization pt3

Some chemical reactions require hydrolysis of 2 “high- energy” bonds to reach completion

A. Achieved by hydrolyzing ATP to AMP & PPi (pyrophosphate), followed by PPi hydrolysis to 2 Pi (inorganic phosphate) (look at pic)

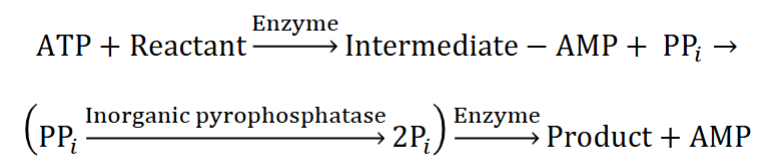

ATP Formation pt1

I. ATP can be formed through a variety of mechanisms

II. Substrate-level phosphorylation

A. Transfer of phosphoryl group from molecules with higher phosphate group-transfer potentials (look at pic)

ATP Formation pt2

Oxidative phosphorylation

A. Nutrient oxidation drives formation of H+ electrochemical gradient

1. Dissipation of this gradient provides G that drives synthesis of ATP from ADP + Pi

2) look at pic

ATP Formation pt3

ATP is an energy transmitter, not a storage reservoir; it’s used as soon as it’s made.

Most cells have enough ATP for 1–2 minutes of energy (only seconds in the brain).

ATP is constantly hydrolyzed and resynthesized.

Cells with high ATP turnover (muscle, brain) use phosphocreatine as a rapid ATP regeneration reservoir.

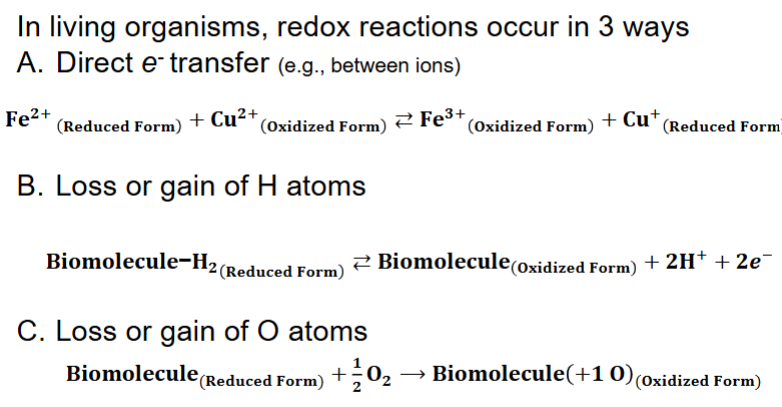

ATP Formation pt4

Creatine kinase (phosphocreatine kinase, enzyme for phosphocreatine)(look at pic)

A. When [ATP] is high, rxn proceeds to right (generate more phosphocreatine)

B. When [ATP] is low, rxn proceeds to left (generate more ATP)

when need energy do reverse rxn

downside of this is that its limited

![<ul><li><p><strong>Creatine kinase </strong>(phosphocreatine kinase, enzyme for phosphocreatine)(look at pic)</p><ul><li><p>A. When [ATP] is high, rxn proceeds to right (generate more phosphocreatine)</p></li><li><p>B. When [ATP] is low, rxn proceeds to left (generate more ATP)</p></li><li><p>when need energy do reverse rxn</p></li><li><p>downside of this is that its limited</p></li></ul></li></ul><p></p>](https://knowt-user-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/17531217-6247-4e43-b763-b5138efa23ea.png)

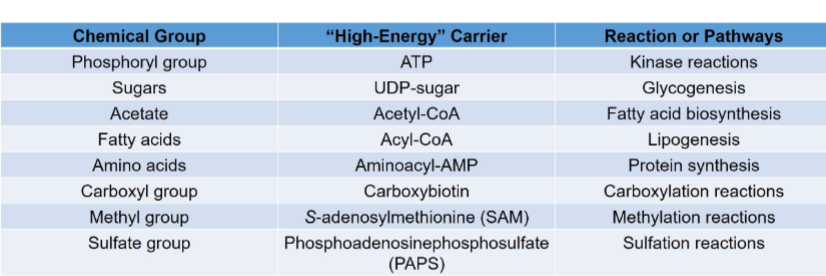

Other “high energy” carriers

ex: atp, udp-sugar, acetyl-coa,

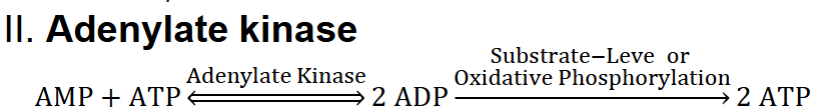

Redox rxns pt 1 (body need redox and energy currency)

Redox reactions (coupled reduction & oxidation) involve transfer of e- between molecules

A. e- transfer is exergonic, providing G that can perform work

B. Oxidation is loss of e- (e- donor is called reducing agent or reductant)

C. Reduction is gain of e- (e- acceptor is oxidizing agent or oxidant)

1. e- are referred to as reducing equivalents

Redox rxns pt 2

Redox reactions are coupled; each molecule has a reduced and oxidized form (redox pair, e.g., NAD++/NADH)-always happen together

Each redox pair has a reduction potential (E, measured in volts, V).

Reduction potential (E) indicates likelihood of electron transfer:

More negative E: redox pair is more likely to be oxidized (donate electrons).

More positive E: redox pair is more likely to be reduced (accept electrons).

Change in reduction potential under biochemical standard conditions is ΔE°

important redox pairs in biochem

oxydized is on right, oxy poor on left

1) energy synthesis

2) energy synthesis

3) importnat antioxidant

4) important for energy metabolism

5) anaerobic metabolism

6) tca cycle

7, 8, 9 import for etc

Q: which is likely to be oxydied and which is reduced ( do this comparing reduction potentials ( look at neg. nad/nadh likely to be oxy, pyruc./lactate likely to be reduced)

q: which member of top pair going to participate nadh bc donate e to pyruvate bc thats e- poor one —> after this ndah goes to nad+ and pyruvate goes to lactate

Oxidized form: On LEFT side, usually electron poor (higher oxidation state)

Reduced form: On RIGHT side, electron rich (lower oxidation state)

![<ul><li><p>oxydized is on right, oxy poor on left</p></li><li><p>1) energy synthesis</p></li><li><p>2) energy synthesis</p></li><li><p>3) importnat antioxidant</p></li><li><p>4) important for energy metabolism</p></li><li><p>5) anaerobic metabolism</p></li><li><p>6) tca cycle</p></li><li><p>7, 8, 9 import for etc</p></li><li><p>Q: which is likely to be oxydied and which is reduced ( do this comparing reduction potentials ( look at neg. nad/nadh likely to be oxy, pyruc./lactate likely to be reduced)</p></li><li><p>q: which member of top pair going to participate nadh bc donate e to pyruvate bc thats e- poor one —> after this ndah goes to nad+ and pyruvate goes to lactate</p></li><li><p><strong>Oxidized form:</strong> On LEFT side, usually electron poor (higher oxidation state)</p></li><li><p class="my-2 [&+p]:mt-4 [&_strong:has(+br)]:inline-block [&_strong:has(+br)]:pb-2"><strong>Reduced form:</strong> On RIGHT side, electron rich (lower oxidation state)</p></li></ul><p></p>](https://knowt-user-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/07392302-c5a4-4c38-a950-f2de918ab814.png)

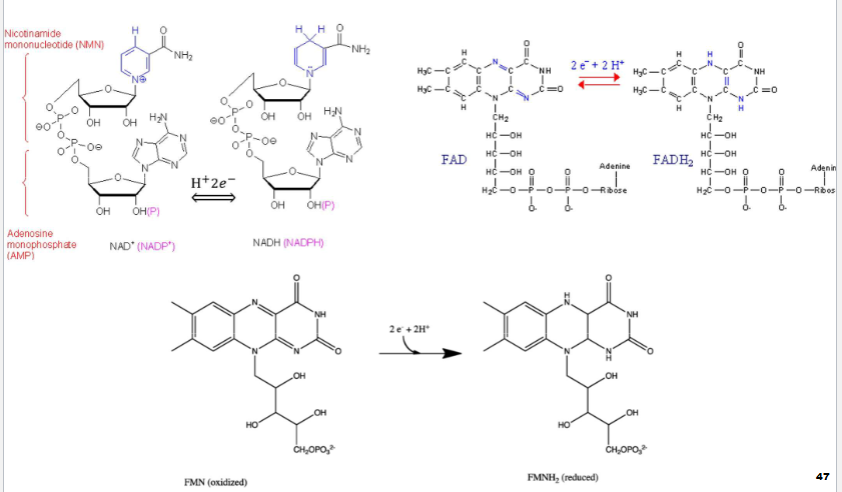

biochem redox rxns pt1

1) is reversible (usually going on in background)

2) is reversible (will see most frequently)

3) is reversible (will see 2nd most freq.)

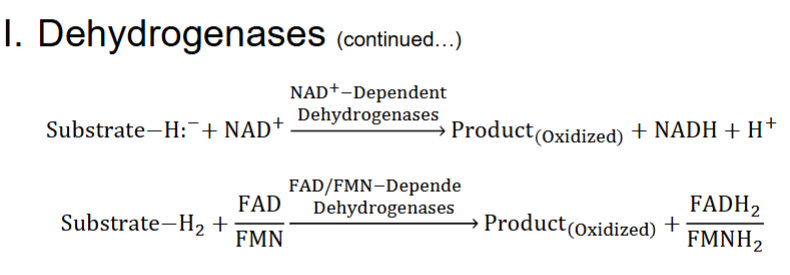

biochem redox rxns pt2

Enzymes catalyzing redox reactions use variety of coenzymes that serve as e- carriers

A. Most important are NAD+, FAD, FMN, & NADPH

II. Dehydrogenases

A. Participate in reactions of oxidative metabolism

1. Located in mitochondria & peroxisomes (some in cytosol)

biochem redox rxns pt3

1) usually stripping off 2H from target substrate

very similar but both H end up in

biochem redox rxns pt4

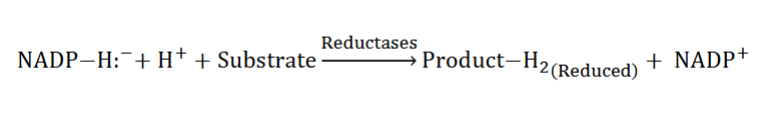

Reductases: Typically catalyzed biosynthetic reactions

1. Utilize NADPH (universal carrier of e- for reductive metabolic reactions) (look at pic)

overview of rxns with mechanisms

1) look at H when reduced 2H

2) when H there now have 2 NH added

3) same for this one